Abstract

Purpose

To conduct a telephone survey establishing pancreatic cancer survivors’ level of interest in, preferences for and perceived barriers and facilitators to participating in exercise and diet intervention programming. These data will inform the development of such interventions for newly-diagnosed patients.

Methods

Seventy-one survivors treated for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma from October 2011 – August 2014 were identified through an institutional cancer registry and contacted via telephone. A telephone survey was conducted to query survivors’ level of interest in, preferences for, and perceived barriers and facilitators to participating in an exercise and dietary intervention program shortly after disease diagnosis. Acceptability of a technology-based visual communication (e.g. Skype™, FaceTime®) intervention was also assessed.

Results

Fifty participants completed the survey (response rate 71.8%). Over two-thirds of participants reported interest in exercise and diet intervention programming. Over half reported comfort with a technology-delivered visual communication intervention. Barriers to participation included older age and physical, personal and emotional problems. The most common facilitator was program awareness. Outcomes for future research important to participants were supportive care and quality of life.

Conclusions

Most pancreatic cancer patients are interested in exercise and diet interventions shortly after diagnosis; however, some barriers to program participation exist.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Future research and intervention planning for pancreatic cancer survivors should focus on developing messaging and strategies that provide support for survivorship outcomes, increase survivor awareness, address lack of familiarity with technology, reduce fears about potential barriers and help survivors overcome these barriers. In so doing, survivorship needs can be better met and quality of life improved in this understudied population.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer effects over 48,000 Americans each year (1). Overall, individuals diagnosed with this disease experience a high symptom burden and reduced health-related quality of life (QOL) due, in part, to the medical and surgical treatment modalities targeted at improving the low survival rate (1-5). Of particular importance is the high prevalence of poor physical functioning that is experienced by this patient population (6, 7) and associated higher mortality (8, 9). Given the small survival benefit of cancer treatment, preservation of QOL and physical functioning is often considered the main treatment goal in pancreatic cancer survivors (10).

Exercise has proven to provide significant health benefits after cancer diagnosis, including improvements in QOL and physical functioning. However, these data are primarily specific to other cancer types (11) and data on the benefits of exercise in pancreatic cancer survivors are limited. To date, only one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of exercise in 102 pancreatic cancer survivors has been published (12). Yeo et al. reported that a home-based walking program with regular self-monitoring was feasible, safe and significantly improved fatigue, physical functioning, and QOL compared to usual care. A noteworthy but non-significant trend towards improved survival was also observed for the walking intervention group compared with the usual care group.

Further research that expands on the Yeo et al. study is warranted. This research should explore the role of exercise after pancreatic cancer diagnosis on clinical outcomes such QOL, fatigue, functional status, recurrence, survival, and potential underlying mechanisms. Such interventions are also anticipated to require concurrent nutritional support given the risk of poor nutritional status, weight loss and cachexia after a pancreatic cancer diagnosis, all of which have been associated with reduced QOL, treatment-related toxicity, increased susceptibility to infection and poorer prognosis (13-15). While previous studies have evaluated the effects of nutrition counseling/support on nutritional status after diagnosis (16), results are mixed and more research on the benefits of nutrition counseling, especially in combination with physical activity, is necessary. To develop optimal interventions that combine exercise and diet programming, it is important to understand the unique interests, preferences, needs and barriers of this survivor population.

The use of technology in cancer survivor care and lifestyle intervention delivery appears to be increasing (17, 18). Previous studies have investigated the level of health-related internet use (17, 19) and shown promise for using various technologies (e.g. e-mail, text messaging, web-based) for home-based delivery of lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors (20-23). However, willingness to use and comfort with technologies may differ by type of cancer group and technology used. Visual communication technologies such as Skype™ and FaceTime® are potentially valuable resources for delivering exercise and diet intervention programming to cancer survivors and have been successfully utilized to deliver such interventions in other populations (24-26). To our knowledge no previous studies have investigated the use of visual communication technologies in cancer survivors and even more specifically, pancreatic cancer survivors.

The purpose of this study was to conduct a telephone survey of survivors previously treated for resectable pancreatic cancer with the goal of collecting data that will inform the development of an exercise and diet intervention for newly-diagnosed patients. The primary aim was to establish survivors’ level of interest in, preferences for and perceived barriers and facilitators to participating in such an intervention program. The secondary aim was to establish survivors’ acceptability of and comfort with a technology-based interventions using visual communication tools such as Skype™ and FaceTime®.

METHODS

Design, Setting and Participants

This was a telephone survey study of pancreatic cancer survivors previously treated at a southeastern academic medical center for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma from October 2011 – August 2014. The survey contained 12 multiple choice/Likert scale items and 4 open-ended items. The telephone survey took approximately 15 – 20 minutes for participants to complete. All study activities were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Prospective patients were identified through the institution's cancer registry and prescreened for eligibility via a medical record review. Exclusion criteria included: 1) non-resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma; 2) under the age of 19; 3) non-English speaking and 4) refusal to participate.

Treating physicians sent letters to eligible participants notifying them of the study and asking their participation in the telephone survey. Approximately one week after letters were posted, study staff called the survivors to conduct the survey, at which time verbal consent was obtained. One hundred-seventeen potentially eligible pancreatic cancer survivors were identified; however, we were unable to make contact with 46 of them as they had invalid phone numbers (n=15), were deceased (n=15), or never answered the telephone (n=16). Of the 71 potential participants for whom contact was made, 51 consented to participate in the telephone survey for a final response rate of 71.8%.

Measures

Introduction/Framing

The following script was used by study staff to introduce participants to the study: “We are conducting a survey of pancreatic cancer survivors to help develop a healthy lifestyle program aimed at helping newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients manage their diet and their ability to be more physically active in such a way that would improve their quality of life. This would involve working with an exercise specialist and a Registered Dietitian. I would like to ask you a few questions about your preferences for such a program.” Participants were then asked by study staff to think back to the first three to six months after their pancreatic cancer diagnosis when responding to all questions. The telephone survey consisted of 16 items.

Participant Characteristics and Program Interest

To collect data on participant characteristics, the survey included questions on demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, race, education, employment, travel time from home to the study institution). A medical record review was also conducted to collect clinical data on treatment type and cancer stage at diagnosis. Participants were queried on their interest in participating in a “healthy lifestyle program” such as that described in the survey introduction that was 1) non-research (i.e. explained as programming offered as part of clinical care and not as a research study) and 2) research-related (i.e., explained as a research study that tested the benefits of the program). Both interest-related survey items used a 5-point Likert scale (not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much).

Barriers, Facilitators, Preferences, and Comfort with technology

An open-ended question asked participants to describe any problems and/or issues that might have interfered with their ability or the likelihood of them participating in a program aimed at increasing their physical activity or improving their diet within the first three to six months after their pancreatic cancer diagnosis (i.e., perceived barriers). A similar open-ended item asked the respondent to describe anything that could be done to increase their likelihood of participating (i.e., perceived facilitators). Survey questions asked participants for their preferences for exercising with an exercise specialist (multiple choice; options were supervised, unsupervised, other, no preference), preferences for exercise location (multiple choice; options were study institution-based, home-based, other, no preference), and preferences for receiving information about exercise and diet (queried about exercise and diet in two separate multiple choice items; options for both were face-to-face, telephone, visual communication such as Skype™ or FaceTime®, other, no preference). Two yes/no items asked participants if they had a smart phone and/or tablet and if they had Wi-Fi in their home. Three items asked participants how comfortable they would be with 1) visual communication such as Skype™ or FaceTime®, 2) visual communication if loaned a tablet and taught how to use it, and 3) using Wi-Fi (5-point Likert scale for each item; not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much).

Pancreatic Cancer Research

Participants were asked to rate their perception of the importance of research addressing physical functioning, QOL and fatigue in pancreatic cancer survivors (5-point Likert; not at all, a little bit, somewhat, quite a bit, very much). Lastly, an open ended question asked participants to identify any other outcomes besides physical functioning, QOL and fatigue (tiredness) that they feel are important to research in pancreatic cancer survivors. An open-ended question also asked if they had any other final comments or suggestions they would like to share with the researchers.

Analytical Procedures

Survey responses were entered into a database and verified for accuracy through quality assurance checks by the research team. Responses to open-ended questions were grouped based on common themes and this was followed by a quality assurance check by a second study staff member. Any inconsistencies in grouping were discussed and resolved by meeting with a third research team member. Responses for interest-related questions were collapsed into two groups to increase statistical power when comparing interest level by other participant characteristics—“Interested” if they responded “quite a bit” or “very interested” and “Not Interested” if responded “not at all,” “a little bit,” or “somewhat interested”. Differences in quantitative survey responses by demographic and clinical characteristics were analyzed using chi-squared tests. All data were analyzed using SPSS (version 22; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set as an alpha level < 0.05.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of the study sample are listed in Table 1. The mean age of study participants was 69 years. The majority of participants were white (84%). Approximately 57% of the participants were female and 34% of the participants had at least a 4-year college degree. The median driving time from home to the academic medical center was 90 minutes (range 12 to 720 minutes). Most participants were diagnosed with Stage 1 or Stage 2 pancreatic cancer, and the median time since surgery was 13 months. At least 45% had received radiation treatment and 65% had received chemotherapy treatment. Data regarding radiation and chemotherapy was unavailable for approximately 25% of participants, likely a result of these participants receiving treatment and surveillance at an institution outside of the hospital system.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (N=50)

| Characteristic | Median (range) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (40-87) |

| Female | 29 (57%) |

| Race | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8 (16%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 43 (84%) |

| ≥ 4 Year College Degree | 17 (34%) |

| Employment | |

| Unemployed | 9 (18%) |

| Employed | 13 (26%) |

| Retired | 24 (48%) |

| Disabled | 4 (8%) |

| Driving time to Medical Center from Home (minutes) | 90 (12 – 720) |

| Cancer Stage | |

| Stage 1 | 10 (20%) |

| Stage 2 | 37 (73%) |

| Stage 3 | 1 (2%) |

| Unknown | 3 (6%) |

| Months Since Surgery | 13 (1-94) |

| Radiation | |

| Yes | 23 (45%) |

| No | 14 (28%) |

| Unknown | 14 (28%) |

| Chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 33 (65%) |

| No | 6 (12%) |

| Unknown | 12 (24%) |

Interest in Exercise and Diet Programming

Most participants (69%) indicated that they would have been interested in participating in a non-research exercise and diet intervention within the first three to six months after their pancreatic cancer diagnosis. Slightly fewer, but still the majority (66%), indicated they would have been interested in participating in a research study testing the benefits of this exercise and diet intervention.

Perception of the Intervention

Perceived Barriers/ Facilitators

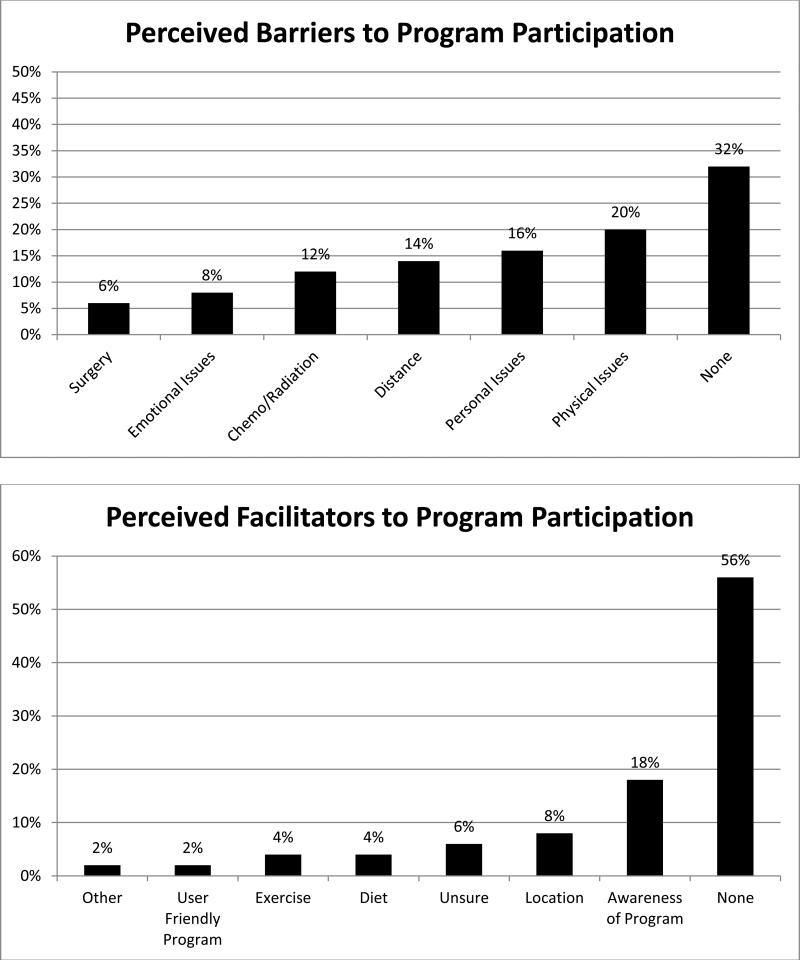

When participants were asked about perceived barriers and facilitators for participation in an exercise and diet intervention within the first three to six months after pancreatic cancer diagnosis, the most common response was “none.” The most commonly reported barriers were physical issues, personal issues, distance, and chemo/radiation (Figure 1). The most commonly reported perceived facilitators to program participation were awareness of program (survivors would like to be informed immediately after diagnosis and adequately educated on the potential benefits of participation) and location (easily accessible or home-based).

Figure 1.

Percent of Participants Reporting Perceived Barriers and Facilitators to Program Participation (N = 50)

Intervention Preferences

Intervention Preferences are shown in Table 2. Half of the participants indicated that they would prefer to do exercise on their own, while 30% indicated they would like to be supervised. The remaining 20% indicated they had no preference regarding exercise supervision. Over half (56%) of participants indicated they would prefer to exercise at home. Participants preferred to receive exercise information in person (34%) or over the phone (22%) and diet information in person (48%).

Table 2.

Intervention Preferences (N=50)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Exercise Supervision Preference | |

| On My Own | 25 (50) |

| Supervised | 15 (30) |

| No Preference | 10 (20) |

| Exercise Location Preference | |

| Medical Center | 4 (8) |

| Home | 28 (56) |

| Other | 12 (24) |

| No Preference | 6 (12) |

| Receive Exercise Information | |

| In Person | 17 (34) |

| Telephone | 11 (22) |

| Skype | 3 (6) |

| Other | 9 (18) |

| No Preference | 10 (20) |

| Receive Diet Information | |

| In Person | 24 (48) |

| Telephone | 8 (16) |

| Skype | 4 (8) |

| Other | 6 (12) |

| No Preference | 8 (16) |

| Technology Outcomes | |

| Use a Smart Phone or Table | 27 (54) |

| Comfort with Loaned Tablet | 29 (58) |

| Use Wi-Fi at Home | 31 (62) |

| Comfort with Wi-Fi* | 25 (81) |

| Comfort with Skype | 22 (44) |

Excludes N=19 participants who responded they do not use Wi-Fi

Comfort with Technology

Technology outcomes with percentages of responses are shown in Table 2. Just over half of the participants had a smart phone or tablet, and slightly more than that reported they would be comfortable using a loaned tablet to interact with an exercise specialist and/or dietitian for delivery of the intervention. Almost two-thirds (62%) of survey participants reported having Wi-Fi at home and of those with Wi-Fi, over three-quarters (81%) reported that they feel comfortable using it. Nearly half (44%) of survey participants reported that they currently feel comfortable using visual communication technology such as Skype™ or FaceTime®.

Pancreatic Cancer Research

Most participants (86%) reported a belief that research that improves physical functioning, quality of life, and fatigue/tiredness in survivors diagnosed with pancreatic cancer is “quite a bit” or “very important”. When asked what other outcomes they felt are important to include in research, they reported psychological support (n=6; e.g. help with coping), side effects (n=5), diet/exercise (n=5), treatment/cure (n=4), etiology (n=4), and screening (n=3) (data not shown).

Differences in Survey Responses by Participant Characteristics

People who were ≥65 years old were significantly less likely to report that they would have been interested in a non-research exercise and diet intervention, comfortable with a loaned tablet, and/or comfortable using a visual communication tool such as Skype™ or FaceTime® to interact with an exercise specialist and/or registered dietitian (percentages by age group provided in Figure 2). Responses did not differ significantly by any other demographic or clinical characteristic (results not shown).

Figure 2.

Differences in Survey Responses by Participant Characteristics (N = 49)

DISCUSSION

Through a telephone survey, this study explored pancreatic cancer survivors’ interest in and preferences for exercise and diet interventions aimed at improving QOL and functional status within the first three to six months after disease diagnosis. We also asked about the acceptability of delivering such interventions using technology. The primary findings were that over two-thirds of survey respondents were enthusiastic about both non-research and research-related exercise and diet intervention programming for newly diagnosed survivors and over half would feel comfortable with a visual communication technology-delivered intervention. Many participants indicated they wish they had received education on diet and exercise during and after treatment. Recent data show that less than one third (28%) of pancreatic cancer survivors reported meeting with a dietitian and even fewer (4%) reported meeting with an exercise physiologist (27) within the first nine months after diagnosis, suggesting these are unmet needs. In addition to exercise and diet, our survey results showed that supportive care and quality of life issues are important outcomes of interest in this population and may also serve as perceived barriers to participation in a post-diagnosis exercise and diet intervention. Overall, results of this study suggest that exercise and diet programming that is tailored to this understudied population is needed. Moreover, our data presents important challenges that must be considered for the planning of future behavioral intervention studies in newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer patients.

When study participants were asked during the telephone survey how they would prefer to receive information, the preferred route was in person or over the telephone for both exercise and diet information. Other information modalities that were mentioned were websites and mailed pamphlets. These results are similar to another recent study that examined the informational needs of gastrointestinal oncology survivors, in which the preferred modalities to receive educational information included pamphlets, websites and one-on-one discussions with healthcare professionals (28). Exercise counseling and program preferences in other cancer groups are comparable, with face-to-face counseling being the preferred modality reported in head and neck (29) and breast (30) cancer survivors.

Although in the current study only 6-8% of participants preferred to receive exercise and diet information via Skype™, over half (56%) of participants reported that they would be comfortable participating in a diet and exercise intervention delivered via Skype™, if they were loaned a tablet and taught how to use it for communicating. This is important because technology-delivered intervention programming has the potential to reach survivors who might otherwise be unable to participate, either due to their geographic location or their illness, and previous research shows that home-based intervention programs are well received in cancer survivors (23). Future interventions could combine delivery strategies, offering the option of receiving information in person during clinic visits with ongoing support provided by telephone or technology based on individual preference.

Over two-thirds of study participants reported they would have been willing to participate in a diet and exercise intervention program within the first three to six months after their diagnosis and over half reported they would feel comfortable using technology to interact with an exercise specialist and/or dietitian. However, older study participants (≥ 65 years old) were significantly less likely than younger survey participants to report that they would have been interested in such an intervention and would feel comfortable with a technology-delivered intervention. As more than two thirds of pancreatic cancer survivors in the United States are over the age of 65 (31) and technology is rapidly evolving to become an integral component of research and clinical care in the modern world, an important next step for future research is to identify ways to help older survivors use new technology. A previous study reported that while the majority of the older adult participants were using the computer, internet and e-mail, only 7% were using visual communication technology (32). Our survey results showed that a much higher percentage (29%) of participants over the age of 65 would be comfortable using visual communication technology if taught how to use it. Future technology-based interventions should include additional strategies aimed at helping older survivors gain confidence in technology use, such as providing training sessions in using smart phones or tablets for video chat.

Physical problems such as fatigue and pain were among the most commonly cited barriers that study participants felt would have interfered with their ability or willingness to participate in an exercise and diet intervention program within the first three to six months after their cancer diagnosis. Results from another study of supportive care needs in pancreatic and ampullary cancer survivors support our findings. Beesley et al. showed that out of five domains, the domain with the greatest need reported by participants was physical/daily living. Needs with pain and fatigue, specifically, were unmet at moderate-to-high levels (27). Fatigue and pain have previously been shown to be associated with significantly impaired health-related QOL and depressive symptoms in pancreatic cancer survivors (5, 33). Evidence supports the benefit of physical activity interventions in combating cancer-related fatigue and improving QOL (34-36), but data on this topic in pancreatic cancer survivors specifically is limited (12) and future research is warranted. The interventions used in such research must include support for dealing with and overcoming these common barriers.

Personal and emotional problems such as scheduling issues, feeling overwhelmed, and difficulty adjusting to changes after cancer diagnosis were other barriers to participating in an exercise and diet intervention that were mentioned by study participants. In the study of the needs of pancreatic cancer survivors conducted by Beesley et al. almost all participants reported having a psychological need that was unmet (27). Future behavioral interventions conducted in this survivor population should be designed with this in mind, perhaps offering psychosocial support as part of the programs or helping participants identify and obtain professional psychosocial support in order to help overcome these barriers.

Interestingly, the most commonly mentioned perceived facilitator to participating in an exercise and diet intervention program within the first few months after diagnosis was simply being aware that such a program exists. Study participants made suggestions such as, “ask patients to participate immediately after diagnosis” and that they would have liked to “hear about the program and its benefits.” Additionally, supportive care and quality of life issues such as psychosocial support, side effects, diet and exercise were the most frequently mentioned outcomes for future research that study participants felt were important, while outcomes related to pancreatic cancer treatment/cure, etiology and screening were mentioned less frequently. These findings further underscore the need for programming and interventions that address these needs in pancreatic cancer patients and survivors.

Importantly, this study is the first to capture information regarding pancreatic cancer survivors’ interest in and preferences for exercise and diet intervention programming and the unique challenges and outcomes that are important to this survivor population. This is of particular importance because needs assessments related to preferences differ on cancer type (37, 38). Moreover, this study examined the acceptability of technology use for diet and exercise interventions, which is a topic on which little is known in any cancer group. Finally, this study adds to the body of literature suggesting that while there is a high demand for diet and nutrition interventions in cancer survivors of all types, these needs are commonly unmet (27, 39-41).

Study results should be considered in light of some limitations. First, it is important to note that the vast majority (93%) of study participants were diagnosed with earlier, stage 1 or 2, pancreatic cancers, indicating our study sample is biased towards healthier survivors with longer survival times. Our sample size is small. However, considering that pancreatic cancer is among the rarer cancer types and has a 5-year survival rate of only 6%, our response rate of 71.5% was excellent. It is possible that conducting a mixed methods study, rather than our current design, would have resulted in a better understanding of how to address discomfort with technology and barriers. However, the budgetary and time constraints we faced while obtaining pilot data needed to guide future research prevented a mixed methods design. In our study, we found that 68% of participants reported that they currently have Wi-Fi at home. However, we did not specify in the survey between Wi-Fi and other internet types and would make this delineation in the future. Knowing exactly what type of internet service survivors have at home is important when planning a technology-delivered intervention program. Furthermore, future studies should investigate the non-technology channels used by older pancreatic cancer survivors to find health information.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that exercise and diet intervention programming that addresses supportive care and QOL issues is desired by pancreatic cancer survivors. Although in-person delivery was the preferred delivery mode, visual communication technology use may also be acceptable, especially among younger survivors and in combination with more conventional delivery strategies depending on individual preferences. While the majority of pancreatic cancer survivors are interested in participating in such a program, barriers to program participation exist such as older age and physical, personal and emotional issues. Future research and intervention planning should focus on developing messaging and strategies that provide support for survivorship outcomes, increase survivor awareness, address lack of familiarity with technology (especially in survivors ≥ 65 years of age), reduce fears about potential barriers and help survivors overcome these barriers. In so doing, survivorship needs can be better met and quality of life improved in this understudied cancer group.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by P30 CA13148; Anna Arthur was supported by NIH/NCI Cancer Prevention and Control Training Grant: R25 CA047888.

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.ACS. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sauerland C, Engelking C, Wickham R, Pearlstone DB. Cancers of the pancreas and hepatobiliary system. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25:76–92. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter R, Stocken DD, Ghaneh P, Bramhall SR, Olah A, Kelemen D, et al. Longitudinal quality of life data can provide insights on the impact of adjuvant treatment for pancreatic cancer-Subset analysis of the ESPAC-1 data. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2009;124:2960–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran TC, van Lanschot JJ, Bruno MJ, van Eijck CH. Functional changes after pancreatoduodenectomy: diagnosis and treatment. Pancreatology. 2009;9:729–37. doi: 10.1159/000264638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller-Nordhorn J, Roll S, Bohmig M, Nocon M, Reich A, Braun C, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer. Digestion. 2006;74:118–25. doi: 10.1159/000098177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieveen van Dijkum EJ, Kuhlmann KF, Terwee CB, Obertop H, de Haes JC, Gouma DJ. Quality of life after curative or palliative surgical treatment of pancreatic and periampullary carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2005;92:471–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaw CM, O'Hanlon DM, McEntee GP. Long-term quality of life following pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:927–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gupta D, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer quality of life questionnaire: implications for prognosis in pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2006;37:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s12029-007-0001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tas F, Sen F, Odabas H, Kilic L, Keskin S, Yildiz I. Performance status of patients is the major prognostic factor at all stages of pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18:839–46. doi: 10.1007/s10147-012-0474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zabernigg A, Giesinger JM, Pall G, Gamper EM, Gattringer K, Wintner LM, et al. Quality of life across chemotherapy lines in patients with cancers of the pancreas and biliary tract. BMC cancer. 2012;12:390. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo TP, Burrell SA, Sauter PK, Kennedy EP, Lavu H, Leiby BE, et al. A progressive postresection walking program significantly improves fatigue and health-related quality of life in pancreas and periampullary cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:463–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.12.017. discussion 75-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vashi P, Popiel B, Lammersfeld C, Gupta D. Outcomes of systematic nutritional assessment and medical nutrition therapy in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2015;44:750–5. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nitenberg G, Raynard B. Nutritional support of the cancer patient: issues and dilemmas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;34:137–68. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mueller TC, Burmeister MA, Bachmann J, Martignoni ME. Cachexia and pancreatic cancer: are there treatment options? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9361–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrucci LM, Bell D, Thornton J, Black G, McCorkle R, Heimburger DC, et al. Nutritional status of patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1729–34. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1011-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beckjord EB, Finney Rutten LJ, Squiers L, Arora NK, Volckmann L, Moser RP, et al. Use of the internet to communicate with health care providers in the United States: estimates from the 2003 and 2005 Health Information National Trends Surveys (HINTS). J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.3.e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valle CG, Tate DF, Mayer DK, Allicock M, Cai J. A randomized trial of a Facebook- based physical activity intervention for young adult cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:355–68. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chou WY, Liu B, Post S, Hesse B. Health-related Internet use among cancer survivors: data from the Health Information National Trends Survey, 2003-2008. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:263–70. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hatchett A, Hallam JS, Ford MA. Evaluation of a social cognitive theory-based email intervention designed to influence the physical activity of survivors of breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013;22:829–36. doi: 10.1002/pon.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spark LC, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG, Reeves MM. Efficacy of a Text Message-Delivered Extended Contact Intervention on Maintenance of Weight Loss, Physical Activity, and Dietary Behavior Change. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3:e88. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goode AD, Lawler SP, Brakenridge CL, Reeves MM, Eakin EG. Telephone, print, and Web-based interventions for physical activity, diet, and weight control among cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:660–82. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bluethmann SM, Vernon SW, Gabriel KP, Murphy CC, Bartholomew LK. Taking the next step: a systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity and behavior change interventions in recent post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:331–42. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3255-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klaren RE, Hubbard EA, Motl RW. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for reducing sedentary behavior in persons with multiple sclerosis: a pilot examination. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:613–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alley S, Jennings C, Plotnikoff RC, Vandelanotte C. My Activity Coach - using video- coaching to assist a web-based computer-tailored physical activity intervention: a randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:738. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ylimaki EL, Kanste O, Heikkinen H, Bloigu R, Kyngas H. The effects of a counselling intervention on lifestyle change in people at risk of cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14:153–61. doi: 10.1177/1474515114521725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beesley VL, Janda M, Goldstein D, Gooden H, Merrett ND, O'Connell DL, et al. A tsunami of unmet needs: pancreatic and ampullary cancer patients' supportive care needs and use of community and allied health services. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papadakos J, Urowitz S, Olmstead C, Jusko Friedman A, Zhu J, Catton P. Informational needs of gastrointestinal oncology patients. Health Expect. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hex.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers LQ, Malone J, Rao K, Courneya KS, Fogleman A, Tippey A, et al. Exercise preferences among patients with head and neck cancer: prevalence and associations with quality of life, symptom severity, depression, and rural residence. Head & neck. 2009;31:994–1005. doi: 10.1002/hed.21053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rogers LQ, Markwell SJ, Verhulst S, McAuley E, Courneya KS. Rural breast cancer survivors: exercise preferences and their determinants. Psychooncology. 2009;18:412–21. doi: 10.1002/pon.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Surveillance Research Program NCI. [2015 October 16];Fast Stats: An interactive tool for access to SEER cancer statistics. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats.

- 32.Vroman KG, Arthanat S, Lysack C. “Who over 65 is online?” Older adults' dispositions toward information communication is technology. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;43:156–66. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsen DP, Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Niedzwiecki D, Passik SD, Tao Y, et al. Pain and depression in patients with newly diagnosed pancreas cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:748–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Capozzi LC, Nishimura KC, McNeely ML, Lau H, Culos-Reed SN. The impact of physical activity on health-related fitness and quality of life for patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mustian KM, Sprod LK, Janelsins M, Peppone LJ, Mohile S. Exercise Recommendations for Cancer-Related Fatigue, Cognitive Impairment, Sleep problems, Depression, Pain, Anxiety, and Physical Dysfunction: A Review. Oncol Hematol Rev. 2012;8:81–8. doi: 10.17925/ohr.2012.08.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, Pescatello SM, Ferrer RA, Johnson BT. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2011;20:123–33. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forbes CC, Blanchard CM, Mummery WK, Courneya KS. A Comparison of Physical Activity Preferences Among Breast, Prostate, and Colorectal Cancer Survivors in Nova Scotia, Canada. J Phys Act Health. 2015;12:823–33. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones LW, Courneya KS. Exercise counseling and programming preferences of cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:208–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.104003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zebrack B. Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:349–57. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zebrack B. Information and service needs for young adult cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:1353–60. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0435-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stull VB, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors: designing programs that meet the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. The Journal of nutrition. 2007;137:243S–8S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]