Abstract

CMP-sialic acid synthetase (CSAS) is a key enzyme of the sialylation pathway. CSAS produces the activated sugar donor, CMP-sialic acid, which serves as a substrate for sialyltransferases to modify glycan termini with sialic acid. Unlike other animal CMP-Sia synthetases that normally localize in the nucleus, Drosophila melanogaster CSAS (DmCSAS) localizes in the cell secretory compartment, predominantly in the Golgi, which suggests that this enzyme has properties distinct from those of its vertebrate counterparts. To test this hypothesis, we purified recombinant DmCSAS and characterised its activity in vitro. Our experiments revealed several unique features of this enzyme. DmCSAS displays specificity for N-acetylneuraminic acid as a substrate, shows preference for lower pH and can function with a broad range of metal cofactors. When tested at a pH corresponding to the Golgi compartment, the enzyme showed significant activity with several metal cations, including Zn2+, Fe2+, Co2+ and Mn2+, while the activity with Mg2+ was found to be low. Protein sequence analysis and site-specific mutagenesis identified an aspartic acid residue that is necessary for enzymatic activity and predicted to be involved in coordinating a metal cofactor. DmCSAS enzymatic activity was found to be essential in vivo for rescuing the phenotype of DmCSAS mutants. Finally, our experiments revealed a steep dependence of the enzymatic activity on temperature. Taken together, our results indicate that DmCSAS underwent evolutionary adaptation to pH and ionic environment different from that of counterpart synthetases in vertebrates. Our data also suggest that environmental temperatures can regulate Drosophila sialylation, thus modulating neural transmission.

Keywords: sialylation, sialic acid, CMP-sialic acid synthetase, enzyme evolution, Drosophila glycosylation

INTRODUCTION

Cytidine monophosphate sialic acid synthetases (CSAS) are evolutionarily conserved enzymes mediating a key step in the biosynthetic pathway of sialylation. They generate the activated sugar donor, CMP-sialic acid (CMP-Sia), from free sialic acid (Sia) and cytidine triphosphate (CTP). The product of CSAS, CMP-Sia, is utilized by sialyltransferase enzymes to modify the termini of glycans attached to glycoproteins and glycolipids and produce various sialoglycoconjugates [1]. These sialylated molecules are eventually delivered to the cell surface or secreted to extracellular milieu, where they mediate a plethora of crucial biological functions [2, 3]. While organisms can possess multiple sialyltransferases (e.g. humans have twenty different sialyltransferase enzymes with distinct linkage and substrate specificities), there is usually only one CSAS (aka CMAS) enzyme mediating the sialic acid activation step in all known organisms mediating de novo sialylation, with the exception of some fish species that have two CSAS genes due to a presumptive gene duplication [4].

CMP-Sia synthetases are unique members of the family of sugar-activating enzymes because they generate an unusual nucleotide sugar donor, CMP-Sia, that represents a nucleoside monophosphate diester, as compared to other activated sugars having a diphosphate diester form. Furthermore, unlike other nucleotide-sugar synthetases that use phosphorylated sugar molecules as substrates, CMP-Sia synthetases can utilize non-phosphorylated sialic acid [5]. Finally, while other sugar-activating enzymes are normally found in the cytoplasm, CSAS localizes to the nucleus in vertebrates, with one reported exception of a zebrafish CMP-Sia synthetase, DreCMAS2, that can be also found in the cytoplasm [6].

Recent studies identified CSAS in Drosophila [7] and found that its function is important for the control of neural transmission [8]. CSAS mutations in Drosophila cause defects in neural excitability and locomotion, while also resulting in temperature-sensitive paralysis and significantly shortened life span [8]. Surprisingly, the DmCSAS protein was found to be localized to the secretory pathway compartment and present mainly in the Golgi when it was expressed in the Drosophila nervous system in vivo or heterologously expressed in mammalian cell cultures [7, 8]. Furthermore, recent experiments revealed that DmCSAS is a glycoprotein modified with N-linked glycans [8]. Thus the DmCSAS represents the first example of CMP-Sia synthetases with Golgi localization, which unveils an unprecedented example of a radical evolutionary change in subcellular localization of a metazoan enzyme that occurred within a family of orthologous proteins with conserved function. The pH and ionic environments of the Golgi and nuclear compartments differ significantly, and thus the unusual subcellular localization of DmCSAS suggests evolutionary adaptation of the enzyme to a distinct molecular environment, which poses important questions about properties of the Drosophila enzyme in comparison to the properties of vertebrate counterparts. While previous studies detected the activity of Drosophila and mosquito CSAS when these enzymes were heterologously expressed in mammalian tissue culture cells [7, 9], insect CSAS proteins were not purified and their enzymatic properties were not characterised. In this work, we purified the DmCSAS protein from Drosophila cultured cells, characterised its enzymatic properties in vitro, and compared them to those of its human orthologue assayed under the same conditions. Along with demonstrating general similarity between enzymatic activity of the Drosophila enzyme and its vertebrate counterparts, our analyses also revealed important differences between them. Our results suggested that insect and vertebrate CMP-Sia synthetases are regulated by different molecular and cellular mechanisms, which shed light on evolutionary adaptation of these proteins to distinct subcellular environments.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials and reagents

Sugars, nucleotides, mouse anti-FLAG antibody and FLAG affinity beads (anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel) were purchased from Sigma. EnzCheck pyrophosphate assay kit was obtained from Invitrogen. PNGaseF enzyme was from NEB. Rabbit GM130 antibody was from Abcam. Drosophila strains with GAL4 drivers were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN). DmCSAS mutants and the FLAG-tagged DmCSAS construct were previously described [8]. GFP-tagged human CMP-sialic acid synthetase construct was a gift from Michael Betenbaugh (The Johns Hopkins University).

Expression constructs, site-directed mutagenesis and cloning

The UAS-CSAS-FLAG expression construct for in vivo expression was described previously [8]. For expression in Drosophila tissue culture cells, the CSAS-FLAG coding region from UAS-CSAS-FLAG was subcloned under control of a metallothionein promoter between Bam HI and Spe I restriction sites of pMK33 vector using regular molecular cloning techniques. For generating the CSAS-DA mutant, we used a PCR-based site-specific mutagenesis protocol [10] and changed the codon 228, GAC to GCC, which resulted in D228A mutation in the CSAS protein. The final expression plasmids for CSAS-FLAG wildtype and DA mutant constructs were confirmed by sequencing and then used in transfection experiments with Drosophila S2 cells to generate stable lines.

Cell culture

Drosophila S2 cells were grown in M3 complete medium supplemented with 10% FBS, bactopeptone (2.5 g/L), yeast extract (1 g/L), penicillin/streptomycin solution (100u/100μg per ml) and fungizone (0.25 μg/ml). Cells were maintained at 25°C in a low-temperature incubator without CO2 control. For transient and stable transfections, we used Ca2+-phosphate protocol as previously described [11] or Effectene reagent (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Polyclonal stable lines were generated using hygromycin selection (200 μg/ml) for 4–6 weeks. Expression of recombinant constructs was induced from metallothionein promoter with 0.7 mM CuSO4 in cultures with cell density of 80–90% confluency. After 20 hours of induction, the cells were collected by centrifugation, washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and then processed for western blot analyses and protein purification.

Protein purification

(i) Drosophila CSAS proteins

The cells with induced protein expression were washed twice with 1xTBS buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and then resuspended in 10 volumes (w/v) of Lysis buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X-100, 1 mM PMSF, and cOmplete protease inhibitors cocktail (Roche)). The cells were lysed by sonication, using Branson Sonifier® 150. Lysis was completed by rocking vials on nutator for 20 min. Non-soluble material was removed from lysates by centrifugation at 14,000g for 20 min. To isolate FLAG-tagged proteins, 20 μl of anti-FLAG affinity beads (Sigma), prewashed in Lysis buffer, were added per 1 ml of lysate. After incubation on a nutator for 4–8 hours, the beads were collected by centrifugation, washed 4 times in Lysis buffer, and then stored at 4°C in Storage buffer (50 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton-X100) until used in assays. All sample manipulations were performed on ice or at +4°C. Concentration and purity of isolated protein was determined by densitometric analysis of proteins separated on 12% SDS-PAGE gels and visualized by Coomassie G250 staining with BSA as quantification standard. Quantification of digitized gel images was performed using TotalLab Quant software.

(ii) Human CSAS protein

GFP-tagged human CSAS protein [7] was expressed in Drosophila using UAS-GAL4 expression system [12] with tubP-Gal4 driver [13]. Flies were homogenized in Dounce grinder using 1.5 ml of Lysis buffer per 100 flies. The homogenized tissue was collected and sonicated by Branson Sonifier using four series of 5-second pulses. The lysis was completed by rocking on nutator for 20 min. The lysates were pre-cleared by centrifugation at 25,000g for 30 min, and then incubated with GFP-affinity beads (Trap-A, Chromotek) prewashed 3 times in Lysis buffer, using 25 μl of beads per 1.5 ml of lysate. After 4–8 hours nutator incubation, the beads were washed 4 times in Lysis buffer and then stored at 4°C in Storage buffer. All manipulations with samples, starting from tissue homogenization, were performed on ice or at +4°C. Protein concentration was determined as described above.

CMP-Sia synthetase in vitro assays

Unless stated otherwise, CSAS assay was performed in Reaction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT) containing 3 mM Neu5Ac and 5 mM CTP. The reaction was started by mixing 200 μl of the reaction mixture with CSAS purified on beads. The reaction was mixed, centrifuged immediately for 30 sec at 3,000 rpm, and then 100 μl of supernatant was withdrawn and kept at −20°C as a sample corresponding to zero-time point. The remaining 100 μl of reaction mixture containing CSAS beads were resuspended and incubated in 0.2 ml PCR tubes with gentle rotations while submerged in a water bath with controlled temperature at 37°C for 1h. The concentration of the Drosophila CSAS protein was typically 200–300 ng per 100 μl of the reaction mixture. Reaction was stopped by transferring reaction tubes on ice for 5 min, followed by centrifugation through 10K Amicon Ultra spin filter (Merck Millipore) to remove beads and protein content. Filtered reactions could be stored at −20° C for up to 6 months without noticeable product degradation. Studies at various pH were performed using two buffers to insure the stability of pH during assays. Cacodylate buffer was used in assays with pH ≤ 7.4 (50 mM sodium cacodylate, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT), while Tris buffer (see above) was used for assays with pH ≥7.4. The pH conditions of the assays were also confirmed by measuring pH after addition of substrates, as adding substrates could substantially affect the final pH of the reaction buffer. DTT was found to be non-essential for CSAS activity and it was not included in assays analyzing the effect of different metal cofactors to avoid metal thiolate complex formation.

The amount of CMP-Sia was quantified using two approaches. In the first one, CMP-Sia was detected by high-performance anion- exchange chromatography (HPAEC) essentially as described previously [14]. Briefly, components of reaction mixture were separated on a 4 × 250 mm CarboPac PA-1 column (Dionex) using Ultimate3000 HPLC system (Thermo) equipped with variable wavelength detector VWD-3100. Column was equilibrated with 5 mM NaOH (eluent A) and elution was performed at flow rate 1 ml/min, using a gradient of 1 M sodium acetate in 5 mM NaOH (10%, 8 min; linear gradient 10–50%, 16 min, linear gradient 50–100%, 6 min; 100%, 12 min). Detection of eluted components was performed at 271 nm. Commercially available CMP-Neu5Ac (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a standard for quantification.

The second approach was based on enzymatic detection of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) by EnzCheck kit (Invitrogen) using manufacturer’s instructions with modifications. In a routine experiment, 5–20 μl from standard CSAS assay were added to EnzChek reaction mixture in total volume 100 μl (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM MESG substrate, 1 U purine nucleoside phosphorylase and 0.05 U inorganic pyrophosphatase) and incubated at 22 °C for 1 hour. The concentration of the product of enzymatic conversion of MESG substrate was detected with Ultrospec 2000 spectrophotometer (Pharmacia Biotech) at 360 nm. PPi concentrations were calculated with calibration curve plotted using PPi standards.

We tested the effect of different components of CMP-Sia synthetase reaction on EnzChek-mediated detection and found that Cu2+, Co2+, Ni2+, Mn2+, Ca2+, Zn2+ and Fe2+ could significantly affect PPi measurements. Thus we resolved to use the HPAEC-based detection of CMP-Sia for CSAS assays in the presence of these ions. We also found that the EnzCheck method can be vulnerable to changes in pH. To overcome this problem, the EnzCheck reactions were adjusted to 150 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, which improved accuracy of PPi quantification.

The HPAEC and EnzCheck – based methods of CMP-Sia quantification were found to produce consistent results and have comparable level of sensitivity over a broad range of substrate concentrations that we tested (~ 3 – 1,000 μM). With exceptions described above, these two methods were used interchangeably in our experiments.

Kinetic analyses

Kinetic parameters were determined for Neu5Ac, Neu5Gc and CTP at saturating concentration of one of the substrates and varied concentration of the second substrate. Assays were conducted at 37°C in 100 μL of reaction mixture consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT and 100 ng of Drosophila CSAS. Rate of reaction was determined using EnzCheck kit as described above. Kinetic parameters (Vmax and Km) were determined by fitting experimental data to the Michaelis-Menten equation, using SigmaPlot v.10 software package (Systat Software, Inc.).

PNGase F treatment

Purified CSAS proteins were eluted from beads by incubation with Glycoprotein Denaturing buffer (0.5% SDS, 40 mM DTT) at 95°C for 10 min. The reaction was briefly chilled, beads were removed by centrifugation, and the eluted protein was diluted 2x by adding H2O, 1% NP40 and 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5. PNGase F (NEB) was added to 500u per 20 μl of reaction, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 31°C for 2 hour. For the mock control, the protocol was repeated with all ingredients except for PNGase F.

Subcellular localization of CSAS-DA

The CSAS-DA mutant protein was expressed in Drosophila larval neurons essentially as described previously [8]. Briefly, the expression was induced in the brain using UAS-GAL4 system [12]. Third instar larval brains were dissected in ice-cold Ringers solution, rinsed and fixed in fresh Fixative solution (4% paraformaldehyde, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 M Pipes pH 7.2) for 20 minutes at room temperature on nutator. Fixed tissue was washed with PBT (PBS pH 7.5, 0.1% Triton X100, 1% BSA, 0.01% sodium azide) and analyzed by immunostaining and epifluorescent microscopy. CSAS-DA-FLAG was detected using mouse anti-FLAG M2 (Sigma) primary antibody (1:2,000). Rabbit GM130 antibody (Abcam) was used at 1:100 dilution. Incubation with fluorescent secondary antibodies was carried out essentially as described previously [15]. The following secondary antibodies and corresponding dilutions were used: goat anti-mouse Alexa-546 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa-488, 1:250 (Molecular Probes). Immunostained brains were mounted in Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed using Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope with ApoTome module for optical sectioning.

In vivo rescue experiments and paralysis assays

For rescue experiments, CSAS wildtype and CSAS-DA were expressed in CSAS loss-of-function homozygous mutant Drosophila [8] using UAS-GAL4 expression system [12]. Temperature-sensitive (TS) paralysis phenotype was assayed essentially as described previously [16]. Briefly, Drosophila strains were maintained using regular cornmeal–malt–yeast food in temperature, humidity and light-controlled environment (25°C, 38% humidity, 12 h light/darkness). For TS-paralysis assays, individual flies were collected on the day of eclosure and aged individually for 5 days. During this period they were transferred once, on day 3, to a fresh-food vial. Five days old flies were transferred to empty vials and temperature was raised to 38°C by submerging vials in a controlled-temperature water bath. We defined paralysis as a condition when a fly was paralyzed and unable to walk or keep standing position for at least 1 minute.

Protein sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis

Protein sequences were aligned using Clustal Omega server at EMBL-EBI [17]. Only N-terminal parts of sequences corresponding to the CMP-Sia synthetase domain were used for enzymes with bipartite domain architecture [4]. Phylogenetic tree was assembled by ClustalW2 program using neighbor-joining algorithm [18].

Statistical analyses

Unless indicated otherwise, all data points show average values obtained from at least three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard errors (SEM). For multiple-groups comparison (TS paralysis assays), one-way ANOVA (Kruskal-Wallis test) was used, followed by a post-hoc Wilcoxon Each Pair nonparametric test, to assess differences between the groups.

RESULTS

Expression, purification and in vitro assays of DmCSAS

DCSAS was previously expressed in vivo as a FLAG-tagged construct that was found to be active based on its ability to rescue the phenotype of DmCSAS mutants [8]. We decided to use that construct in purification experiments. To this end, the CSAS-FLAG protein was expressed in Drosophila S2 cell culture and purified using FLAG-affinity beads. The amount and purity of CSAS was evaluated by Coomassie staining of purified proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. The identity of CSAS bands on Coomassie-stained gels was confirmed by western blots (Fig. 1A). Purified CSAS was present on the gel as two bands corresponding to the two glycoforms of the protein that were previously detected in vivo [8]. We were able to consistently isolate up to 0.5 μg of CSAS per 1 ml of culture with a purity of about 90%, as estimated by the relative amount of CSAS compared to non-specific proteins co-purified on FLAG-affinity beads.

Figure 1.

Purification of Drosophila CSAS protein and its in vitro enzymatic activity. A, DmCSAS-FLAG protein purified on FLAG-affinity beads and analyzed by Coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE gels and western blot. Lane 1, non-specific proteins purified from S2 cells without DmCSAS-FLAG expression. Lane 2, DmCSAS-FLAG purified from S2 cells. Lane 3: western blot analysis of purified DmCSAS (same sample as on lane 2). The positions of two DmCSAS glycoforms, as well as heavy and light chains of FLAG antibody leached from the beads are indicated. B, HPLC chromatograms illustrating the detection of CMP-Neu5Ac. The top trace shows CMP-Neu5Ac acid standard as a control. Traces below show the gradual increase of CMP-Neu5Ac product over a period of 90 min in the assay with purified DmCSAS. C, Purified DmCSAS can stably produce CMP-Neu5Ac for up to 90 min. The assays were carried our at standard reaction conditions (100mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT, 3 mM sialic acid, 5.5 mM CTP, and 100 ng DmCSAS) at 40°C.

Purified DmCSAS protein has a stable CMP-sialic acid synthetase activity

Enzymatic activity of purified CSAS was assayed in vitro using CTP and Sia as substrates (see Experimental Procedures for details). We quantified the product of catalytic activity, CMP-Sia, by HPLC (the identity of product peaks was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Supplementary Material Fig. S1, Table S1)) as well as by the enzymatic detection of pyrophosphate, a byproduct of the CMP-Sia synthesis reaction (see Experimental Procedures). These two assays were compared in a number of experiments, which indicated that the assays produce consistent results and have similar sensitivity. Thus, we used the two assays interchangeably in our further experiments.

In our initial assays, we tested whether CSAS has a stable CMP-synthetase activity in vitro. Our experiments indicated that the purified enzyme was active and able to generate CMP-Sia in vitro with constant productivity for up to 90 minutes at 40°C (Fig. 1B–C).

Effect of temperature and pH on DmCSAS activity

We characterised the dependence of DmCSAS activity on temperature and pH. We found that the activity steadily increases with temperature from 20°C to 45°C by approximately an order of magnitude (Fig. 2A). The activity declines dramatically at temperatures above 45°C, which probably reflects the decrease of the protein stability at higher temperature.

Figure 2.

Effect of temperature and pH on DmCSAS activity. A, The dependence of enzyme activity on temperature. B, The dependence of enzyme activity on pH. Unless indicated otherwise, assays were performed at standard reaction conditions in the presence of 20 mM Mg2+ at 37°C, pH 8. Cacodylate buffer was used in assays with pH ≤ 7.4 (diamonds) and Tris-HCl buffer was used at pH ≥ 7.2 (squares).

The analysis of the dependence of DmCSAS activity on pH revealed that the enzyme has a relatively narrow optimum around pH 8 (Fig. 2B). In standard assay conditions, DmCSAS activity declines precipitously at lower pH, dropping to 20% around pH 7.4 and becoming practically negligible below pH 7.0. This result was surprising considering that DmCSAS localizes predominantly to the Golgi compartment that has estimated pH in the range of 6.2–6.7 [19, 20]. Above the optimal pH, the DmCSAS activity also declines substantially but more gradually, loosing ~ 50% at pH 9. Thus, in comparison to its mammalian and bacterial counterparts that generally have a broader optimum of activity at more basic pH conditions (pH 8.5–10 [21–23]), the Drosophila enzyme demonstrates the pH dependence with a relatively sharp optimum that is shifted toward lower pH.

Substrate specificity of DmCSAS

We further characterised the activity of DmCSAS by assessing its specificity. We measured its kinetic parameters for a number of substrates, including several types of sialic acid and structurally similar molecules found in various organisms. The apparent Km values were 410 μM and 450 μM for N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and CTP, respectively (Fig. 3 A–B). Estimated Vmax for these substrates was in the range of 3.4–3.6 μmol/min/mg. Other nucleoside triphosphates, including ATP, GTP and UTP, along with CDP and CMP, were also tested as potential substrates. However, none of them could be utilized by the enzyme (data not shown). We also tested N-glycolylneuraminic acid (Neu5Gc), another common sialic acid variant present in vertebrate species [1]. While CMP-Neu5Gc is usually produced in mammalian cells from CMP-Neu5Ac by CMP-Neu5Ac hydroxylase, human cells lack this enzyme and can generate CMP-Neu5Gc by CSAS, indicating that CSAS-mediated activation of Neu5Gc from dietary sources and salvage pathway play biological roles in animal organisms [24–26]. In comparison to Neu5Ac, Neu5Gc was found to be a relatively inferior substrate for DmCSAS. The kinetics for Neu5Gc showed no saturation, so we could only estimate that the Km for Neu5Gc was > 3.5 mM (Fig. 3C). Considering that the structural difference between Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc is relatively small, including just the hydroxylation of the 5-N-acetyl group in Neu5Gc, this result suggests that the N-acetyl group of sialic acid plays an important role in CSAS substrate recognition.

Figure 3.

Kinetic analysis of DmCSAS and comparison of substrate specificities of Drosophila and human CMP-Sia synthetases. A–C, Graphs show kinetics for CTP (A), Neu5Ac (B), and Neu5Gc (C). D–E, Substrate specificities of purified DmCSAS (D) and HsCSAS (E) with Neu5Ac, Neu5Gc, KDN and KDO as tested substrates. Unless indicated otherwise, assays were performed using standard reaction conditions that included 100mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 20mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM DTT, 3 mM sugar substrate, and 5.5 mM CTP. Drosophila and human enzymes were used at 100 ng and 30 ng per reaction, respectively. Reactions were incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The identity of CMP-Neu5Ac and CMP-Neu5Gc products was confirmed by MS analyses (see Supplementary Materal, Fig. S1 and Table S1).

In addition, two other structurally related sugars were tested as substrates, 2-keto-3-deoxynononic acid (KDN) and 2-keto-3-deoxyoctonic acid 3-deoxy-D-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO). The former is a common type of sialic acid abundantly present in simpler vertebrate species [27], while the latter is an eight-carbon sugar that is structurally similar to sialic acids and commonly found in Gram-negative bacteria and higher plants [28, 29]. We found that CSAS has a nearly undetectable activity toward KDN, while no activity was detected with KDO (Fig. 3D). In order to compare the activity of Drosophila CSAS to a mammalian counterpart assayed in similar conditions, we expressed human CMP-Sia synthetase (HsCSAS) in Drosophila cells and purified it on affinity beads (see Experimental Procedures). This recombinant human enzyme was found to be significantly more active when compared to DmCSAS, having ~ 20 times higher activity at 37°C in the same assay conditions. The relative preference for sialic acid substrates was very different for HsCSAS which showed equal activities toward Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc, and lower but still significant activity toward KDN. Similar to the Drosophila enzyme, HsCSAS could not utilize KDO as a substrate (Fig. 3E).

Requirement for divalent metal cations

Previous studies revealed that divalent metals, such as Mg2+ or Mn2+, are essential for the activity CMP-Sia synthetases as these metal ions bind in the vicinity of the enzyme active site and facilitate the orientation of substrates and catalysis [4]. Mg2+ is thought to be the preferred metal cofactor for CMP-Sia synthetases, and it was used in the majority of previous studies on in vitro activities of the synthetases. Hence, we first examined the requirement for the metal ions for DmCSAS activity by varying the concentration of Mg2+ in the reaction buffer. The enzyme was not active without a metal cofactor, and CSAS activity reached saturation at ~20–30 mM Mg2+ (Fig 4A).

Figure 4.

Effect of metal ions on CMP-Sia synthetase activity. A, DmCSAS requires the presence of divalent metal cations for its activity. The enzyme was assayed at different concentrations of Mg2+. B, DmCSAS can utilize different metal cofactors, while metal cofactors have differential effects on DmCSAS activity at distinct pH. C, Human CMP-Sia synthetase assayed with different metal ions at the same reaction conditions as the Drosophila enzyme in B. D–E, Substrate specificity (D) and temperature dependence (E) of DmCSAS activity in presence Mn2+ as a cofactor at pH 7.6. Unless indicated otherwise, assays were performed in standard reaction conditions using corresponding metal cofactor at 5 mM.

Interestingly, a previous study found that using Mn2+ instead of Mg2+ caused a shift of pH optimum of the bovine CMP-Sia synthetase to more neutral values, from ~ 9.5 to 8.0 [30].

Thus, we decided to test whether DmCSAS could utilize divalent metal cations other than Mg2+, and whether these other metals could activate Drosophila CSAS at pH 6.5 that corresponds to the endogenous environment of this synthetase in the Golgi compartment. We examined the activity of DmCSAS at pH 6.5 and 7.6 in the presence of different divalent metal cations (Fig. 4B). The effect of cations was analyzed at 5 mM concentration to avoid precipitation of the reaction mixture that was observed at higher concentrations for some ions, such as Mn2+ and Cu+2 (this concentration is also expected to be more physiologically relevant [31]). For comparison, the activity of human CMP-Sia synthetase was also analyzed in parallel experiments using the same conditions (Fig. 4C). We found that DmCSAS exhibits significant activity at pH 6.5 in the presence of Mn2+, Co2+, Zn2+, Fe2+ and Ni2+. All of these metals yielded a higher activity than Mg2+ at pH 6.5, while the activity with Mn2+ and Co2+ surpassed that with Mg2+ at pH 7.6 as well. These two preferred metal cofactors were also found to be the best cofactors for the human synthetase at the both pH conditions. However, the human enzyme was inactive in the presence of Zn2+ and Fe2+, irrespectively of pH (Fig. 4C). These data suggest that Drosophila CSAS can endogenously utilize a metal ion other than Mg2+ while working in a lower pH environment inside the Golgi compartment.

To test whether different metal cofactors may influence substrate specificity of DmCSAS, we assayed the enzyme in presence of Mn2+ with different types of sialic acids. We found that DmCSAS substrate preference was essentially the same with Mn2+ as with Mg2+ (Fig. 4D vs. 3D). Utilization of Mn2+ instead of Mg2+ somewhat enhanced the dependence of enzyme activity on temperature, which was found to increase 14 fold between 20°C and 45°C in presence of Mn2+ (as compared to10 fold increase in presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 4E vs. 2A)). Taken together, these results suggested that substrate specificity and temperature dependence of DmCSAS activity do not significantly change when the enzyme utilizes different metal cofactors.

The role of conserved aspartic acid residues

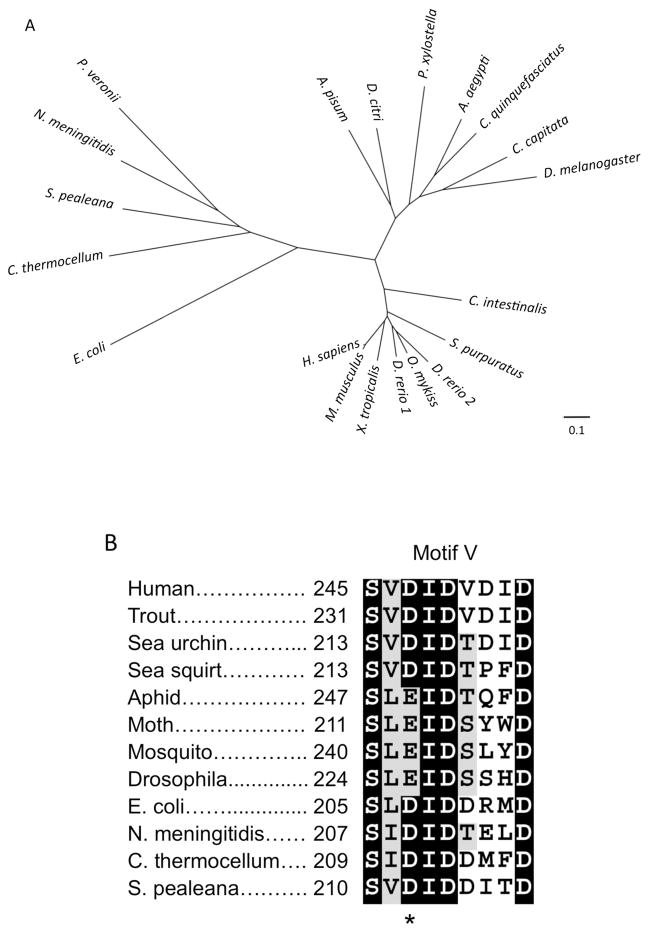

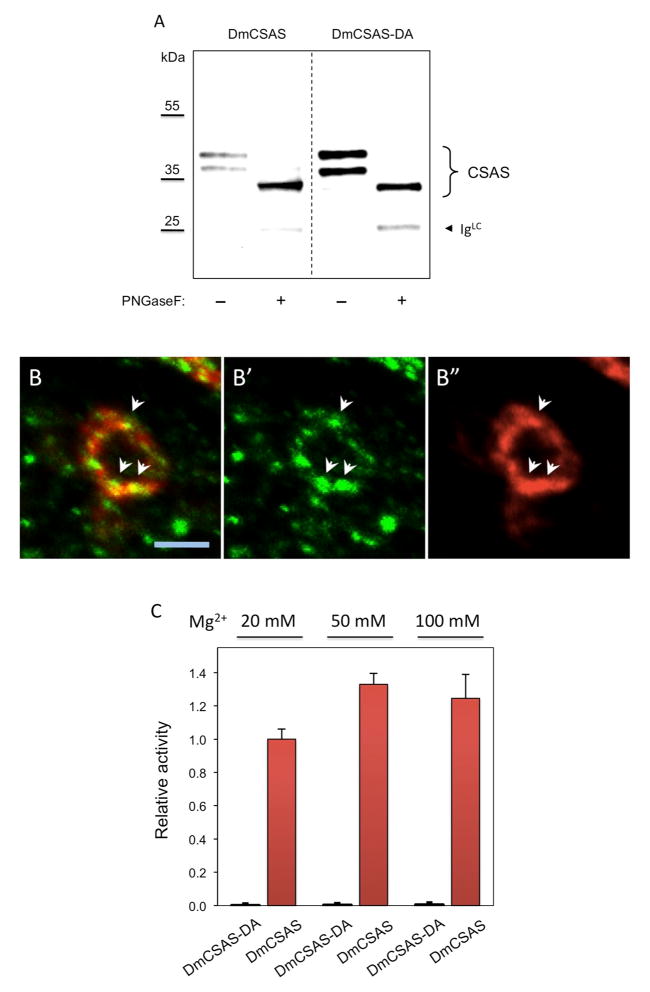

Our phylogenetic analysis of CMP-Sia synthetase sequences from different species indicated that these enzymes in insects, more complex animals (such as tunicates and vertebrates) and bacteria represent three different well-separated clades (Fig. 5A). The clear phylogenetic separation between synthetases from insects and vertebrates presumably reflects the fact that these enzyme subfamilies evolved in distinct subcellular environments, as insect CSAS proteins are predicted to localize to the secretory compartment due to the presence of a putative signal peptide sequence, while the vertebrate enzymes are nuclear-localized proteins. Since the adaptation of insect synthetases to the milieu of the Golgi compartment is potentially associated with utilizing different metal cofactors (Fig. 4B), the insect enzymes may have evolved distinct interactions with metal cations. Thus, we decided to examine more closely the amino acid sequences of insect CSAS proteins, while focusing on the residues that are predicted to coordinate metal cations within catalytic centers. Two conserved aspartic acid residues in the motif V were proposed to coordinate metal cations at the active site of mammalian and bacterial CMP-Sia synthetase [32–34]. Interestingly, the sequence alignment of the motif V indicated that one of these aspartic acids, thought to be essential for coordinating the catalytic metal ion [34], is not conserved in insect enzymes (Fig. 5B). This observation suggested that metal cofactors are bound differently in the insect enzymes, being primarily coordinated by one aspartic acid. Therefore mutating this remaining conserved Asp residue is predicted to completely eliminate enzymatic activity. To test this hypothesis, we created a DmCSAS-DA mutant that has the D228A substitution. This mutant was expressed in Drosophila S2 cultured cells and the CNS in vivo and its level of expression, subcellular localization and glycosylation were analyzed and compared to that of the wildtype DmCSAS protein. These experiments revealed no significant differences between DmCSAS-DA and wildtype DmCSAS, which indicated that the mutant protein was folded properly within the cell (Fig 6A–B and data not shown). At the same time, we could not detect any measurable activity of DmCSAS-DA when it was purified and assayed in vitro, even at increased Mg2+ concentration (Fig. 6C), the condition that was previously shown to elevate the activity of a bacterial CMP-Sia synthetase with the analogous mutation [34]. These results indicated that D228 is essential for DmCSAS catalytic activity and suggested that this residue plays a key role in coordinating metal cation in the enzyme active site. We also tested the activity of DmCSAS-DA in vivo using temperature-sensitive paralysis assays. DmCSAS mutant flies are paralyzed at elevated temperature due to abnormalities in neural transmission. This phenotype can be rescued by transgenic expression of DmCSAS [8]. The DmCSAS-DA protein was unable to rescue the phenotype (Fig. 6D), which indicated that enzymatic activity is essential for DmCSAS function in vivo.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis and metal binding site comparison between CMP-Sia synthetases from different species. A, Phylogenetic tree illustrating evolutionary relationship between CMP-Sia synthetases from bacteria, insects and complex animals (deuterostomes). The tree was built by ClustalW2 program using neighbor-joining algorithm. The accession numbers of bacterial sequences: Pseudomonas veronii, WP_017848838.1; Shewanella pealeana, CP000851.1; Clostridium thermocellum, CP002416.1; Neisseria meningitidis, AAB60780.1; Escherichia coli, J05023.1. The accession numbers of insect proteins: Acyrthosiphon pisum (pea aphid), NP_001156112.1; Diaphorina citri (Asian citrus psyllid), XM_008472953.1; Plutella xylostella (moth), XM_011559466.1; Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito), XM_001662967.1; Culex quinquefasciatus (southern house mosquito) XP_001842321.1; Ceratitis capitata (Mediterranean fruit fly), XM_004522975.1. The accession numbers of deuterostome proteins: Ciona intestinalis (sea squirt), NM_001100127.1; Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (sea urchin) CSAS NM_001126308.1; Danio rerio (zebrafish) JQ015186.1, JQ015187.1; Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout), NM_001124190.1; Xenopus tropicalis (frog), NM_001097281.1; Mus musculus (mouse), NP_034038.2; Homo sapiens (human), NP_061156.1. B, The fragment of CMP-Sia synthetase multiple sequence alignment showing the conserved Motif V involved in metal cofactor coordination. Asterisk indicates the aspartic acid residue of the DID triad that is conserved in bacterial and vertebrate sequences but is substituted by glutamic acid in insect CSAS proteins. The multiple alignments were generated by Clustal Omega server at EMBL.

Figure 6.

Analyses of the DmCSAS-DA mutant protein. A, DmCSAS-DA (DmCSAS with D228->A substitution) is properly glycosylated, as indicated by PNGase F treatment. DmCSAS wildtype protein was used as a control. Proteins were purified on FLAG affinity beads, treated with PNGase F, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by western blot detection. Both proteins are expressed as two glycoforms represented by two bands on the gel. Upon PNGaseF – mediated removal of N-glycans, these bands collapse into one band of a lower molecular mass corresponding to deglycosylated protein. B, DmCSAS-DA is localized in the Golgi compartment when expressed in the CNS neurons in vivo, as reveled by double immunofluorescent staining with the GM130 Golgi marker [47]. B′ and B″ show single channel staining for GM130 (green) and DmCSAS-DA (red), respectively. B is the overlay of B′ and B″. Arrows point at examples of co-localization between GM130 and DmCSAS-DA. DmCSAS-DA was expressed in the CNS using UAS-GAL4 system. Images of fixed, dissected and stained brains were obtained using epifluorescent microscopy with optical sectioning. The image shows a confocal section through the cell body of a single neuron. Scale bar is 5 μm. C, CMP-Sia synthetase activity assays of DmCSAS-DA mutant at increasing concentrations of Mg2+. DmCSAS wildtype protein was used as a positive control. No enzymatic activity of DmCSAS-DA was detected. D, DmCSAS activity was tested in vivo using a transgenic rescue approach. DmCSAS-DA and DmCSAS wildtype proteins were expressed in DmCSAS homozygous null mutants (DmCSAS−) using UAS-GAL4 system. The rescue of DmCSAS− phenotype was analyzed by TS-paralysis assays. At least 20 flies were assayed for each genotype. o and *** indicate not statistically significant and highly significant differences, respectively. Error bars represent SEM in all panels.

DISCUSSION

Our work provided the detailed characterisation of purified Drosophila CMP-Sia synthetase, the first purified and characterised member of the subfamily of CSAS proteins with unique secretory compartment localization. The phylogenetic comparison between insect and vertebrate CMP-Sia synthetases indicated that the insect enzymes belong to a separate clade of proteins (Fig. 5). This clear separation suggests that their evolution was significantly affected by differences in physiological environment, as insect CSAS proteins are predicted to work in the secretory pathway compartment, while vertebrate CMP-Sia synthetases are normally localized to the nucleus.

The phylogenetic separation between insect CSAS and their counterparts from more complex animals is consistent with unique enzymatic properties of the Drosophila CMP-Sia synthetase that were revealed in our experiments. Unlike most other characterised synthetases that prefer relatively basic pH conditions, the Drosophila enzyme shows preference for lower pH, with a sharp optimum around pH 8.0 in the presence of Mg2+ as a cofactor (Fig. 2B). Surprisingly, we found that the activity of the enzyme is negligible at the pH corresponding to the conditions inside the Golgi (6.3–6.7), the subcellular locale where the enzyme is predominantly found in vivo [8]. This apparent conundrum can be resolved by the fact that the synthetase is able to efficiently utilize several metal cofactors beside Mg2+, while showing significant activity with some of them at lower pH conditions. Remarkably, in the presence of Zn2+ and Fe2+ the activity is even higher at pH 6.5 than at 7.6 (Fig. 4B). On the other hand, our data on the recombinant human CMP-Sia synthetase, purified and assayed in vitro using the same conditions, indicate that fewer metals can activate the human enzyme (Fig. 4C). This observation is consistent with previously published data on other vertebrate CSAS orthologues [23]. The human CMP-Sia synthetase is unable to utilize Zn2+ and Fe2+, while showing higher activity at pH 7.6, as compared to 6.5, with all tested cofactors (Fig. 4C). These differences between the human and Drosophila enzyme support the hypothesis of evolutionary adaptation of these enzymes to distinct subcellular environments. Interestingly, Zn2+ and Fe2+ are both present in Drosophila at relatively high levels [35]. They are essential for Drosophila development and physiology and known to be specifically transported to the Golgi compartment [36, 37], which indicates that these metal ions are reasonable candidates for endogenous cofactors of DmCSAS.

The presence of divalent metal cations is a strict requirement for the activity of CMP-Sia synthetase [4], including Drosophila CSAS (Fig. 4A). So far, however, no metal cofactors have been revealed on crystal structures of these enzymes [4]. The position of metal ions and the residues that coordinate them were proposed based on models using the structural information on bacterial CMP-Kdo synthetases, enzymes with similar fold architecture [38, 39]. These models suggested that the catalytic metal cation is coordinated by two aspartic acids within the conserved DID triad of the CSAS motif V [4, 34, 38]. Surprisingly, our sequence alignments revealed that the first D in this motif is not conserved and is substituted with E in insect CSAS sequences (Fig. 5B). This observation further supports the idea that the molecular evolution of insect CSAS enzymes resulted in metal cofactor interactions that are different from those of CMP-Sia synthetases localized outside of the secretory compartment. The importance of the remaining D residue conserved in insect enzymes was examined in our analyses of DmCSAS-DA, the mutant version of DmCSAS with D228A substitution. The level of expression, subcellular localization and glycosylation of this mutant were all similar to those of the wildtype protein, which strongly suggested that DmCSAS-DA was normally expressed and properly folded (Fig. 6A–B). However, we could not detect any enzymatic activity of the DmCSAS-DA protein. The analogous D211A mutation in the CMP-Sia synthetase from N. meningitidis also resulted in significant loss of activity, however some residual activity still remained [34]. Moreover, increased Mg2+ concentration was able to partially restore the activity of that mutant, while the mutation in the first D of the DID triad (D209 in the N. meningitidis sequence, Fig. 5B) caused a more dramatic loss of activity and was not restored by increased metal concentration [34]. Thus, the D209 of N. meningitidis appears to play a more important role in metal binding than D211, which is consistent with putative bidentate interactions of D209 with a metal cofactor proposed by analogy to CMP-Kdo synthetases [34, 38]. On the other hand, the activity of DmCSAS-DA was not detectable even at elevated metal concentrations (Fig. 6C), which suggests that the key role of metal cofactor coordination is “reassigned” in Drosophila CSAS to the last residue of the (D/E)ID triad of the motif V. Taken together, our data suggested that the coordination of catalytic metal cofactors is different in insect CMP-Sia synthetases, as compared to vertebrate and bacterial counterparts. Our results also demonstrated that the aspartic acid residue of the EID triad is essential for the activity of DmCSAS and suggested that this residue plays similar role in other insect CSAS enzymes.

We also analyzed the activity of DmCSAS-DA in vivo using a transgenic rescue approach, which revealed that enzymatic activity of DmCSAS is essential for its biological function (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, previous genetic interaction experiments suggested that DmCSAS could potentially have some non-enzymatic functions in vivo, while studies in vertebrate systems have also led to speculations that CSAS proteins may have some yet unidentified role not associated with their CMP-Sia synthetase activity. Our experiments provided the first in vivo test for potential non-enzymatic functions of CSAS proteins. While it remains possible that DmCSAS has some in vivo functions not directly associated with its enzymatic activity, they are probably minor as our data demonstrated that DmCSAS enzymatic activity is essential for the main biological role of DmCSAS in maintaining normal neural transmission.

Our characterisation of substrate specificity of Drosophila CSAS indicated that the enzyme is very selective in utilizing certain types of sialic acids. It shows the highest activity toward Neu5Ac, having Km value among the lowest reported for animal CMP-Sia synthetases (e.g., Km of the synthetase purified from rat, 0.72–1.3 mM; frog, 1.6 mM; hog, 0.8 mM; calf, 0.9–1.4 mM [21, 40–42]), which is consistent with the fact that the concentration of sialic acid in Drosophila is low [43, 44]. Despite subtle structural differences between Neu5Ac and Neu5Gc (just a single hydroxylation of the 5-N-acetyl group in Neu5Gc [1]), the latter is a significantly poorer substrate for the Drosophila enzyme (Fig. 3). Mammalian CMP-Sia synthetases commonly do not discriminate between these sialic acid versions (Fig. 3E, [21, 23]), suggesting that the N-acetyl group plays a more important role in DmCSAS substrate recognition, as compared to mammalian CMP-Sia synthetases. This conclusion is consistent with the fact that KDN, a desamino form of sialic acid that carries a hydroxyl instead of the N-acetyl group [1], cannot be utilized by the Drosophila enzyme (Fig. 3D, 4D). KDN is a common type of sialic acid present in simpler vertebrates [27], and the possibility that Drosophila can also synthesize KDN-modified glycans was previously discussed [45]. Our results now indicate that this scenario is unlikely since the CSAS protein is thought to be the only enzyme that can activate sialic acids in Drosophila [8, 45].

Our analyses of DmCSAS activity at different temperature conditions revealed a remarkable stability of the enzyme and a robust increase of enzymatic activity at elevated temperatures up to 45°C (Fig. 2A). For comparison, the counterpart enzymes from ectothermic vertebrates were found to reach optimum at 37 °C (frog CSAS [40]) or be unstable at a higher temperature (the trout CSAS is unstable above 25° C [46]), whereas most bacterial synthetases have optimum at 37 °C [22]. Intriguingly, DmCSAS activity increases ≥9 fold between 20°C and 40°C (Fig. 2A, 4E), within the range of temperature of Drosophila natural habitats. Drosophila is a poikilotherm, having organism’s temperature regulated by ambient conditions. These data indicate that environmental temperature can potentially play an important role in the regulation of Drosophila sialylation. Our previous experiments revealed that CSAS is essential for the regulation of neural excitability. In vivo analyses demonstrated that Drosophila CSAS mutants cannot maintain a sustainable level of neural activity and are paralyzed at elevated temperature (Fig. 6C, [8]). Thus, the significant temperature-dependent increase in DmCSAS enzymatic activity can potentially underlie a novel regulatory mechanism that controls the level of neural activity at different environmental temperatures, which is expected to have important implications for Drosophila neurophysiology and behavior.

Supplementary Material

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

DmCSAS has unique localization in the cell secretory compartment. Our results demonstrated that DmCSAS has unusual enzymatic properties that revealed evolutionary adaptation to the milieu of the Golgi compartment and suggested mechanisms that control sialylation in insect organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Betenbaugh for human CMP-Sia synthetase plasmid. We are grateful to Paul Lindahl, Frank Raushel and all members of Panin laboratory for valuable discussions. We appreciate help of Dmitry Lyalin, Michiko Nakamura and Thomas Hunt with molecular cloning and tissue culture experiments. We are thankful to Ryan Baker and Daria Panina for comments on this manuscript. We acknowledge the use of Drosophila strains from the Bloomington Stock Center at Indiana University. We also acknowledge support provided by TAMU OVPR Research Development Fund for Metabolomics Core MS instrumentation in Protein Chemistry Laboratory directed by LD.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grant NS075534 to VMP.

Abbreviations

- Sia

sialic acid

- Neu5Ac

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- Neu5Gc

N-glycolylneuraminic acid

- KDN

2-keto-3-deoxy-D-glycero-D-galacto-nononic acid

- KDO

2-keto-3-deoxy-D-mannooctanoic acid

- PPi

inorganic pyrophosphate

- CMP-Neu5Ac

cytidine monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid

- CMP-Sia

cytidine monophosphate sialic acid

- CSAS

CMP-sialic acid synthetase

- CMAS

cytidine monophosphate N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HPAEC

high-performance anion-exchange chromatography

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- UAS

upstream activation sequence

- CNS

central nervous system

- MS

mass spectrometry

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

ABM, BNN and VMP designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. ABM, BNN and HS performed the experiments and analyzed experimental data. HS also assisted in the editing of the manuscript. LD performed MS analyses and helped with MS data interpretation.

References

- 1.Varki A, Schauer R. Sialic Acids. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME, editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2009. pp. 199–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varki A. Sialic acids as ligands in recognition phenomena. FASEB J. 1997;11:248–255. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.4.9068613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varki A. Sialic acids in human health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellmeier M, Weinhold B, Münster-Kühnel A. CMP-Sialic Acid Synthetase: The Point of Constriction in the Sialylation Pathway. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 1–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeze HH, Elbein AD. Glycosylation Precursors. In: Varki A, Cummings RD, Esko JD, Freeze HH, Stanley P, Bertozzi CR, Hart GW, Etzler ME, editors. Essentials of Glycobiology. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 2009. pp. 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaper W, Bentrop J, Ustinova J, Blume L, Kats E, Tiralongo J, Weinhold B, Bastmeyer M, Munster-Kuhnel AK. Identification and biochemical characterization of two functional CMP-sialic acid synthetases in Danio rerio. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13239–13248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.327544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Viswanathan K, Tomiya N, Park J, Singh S, Lee YC, Palter K, Betenbaugh MJ. Expression of a functional Drosophila melanogaster CMP-sialic acid synthetase. Differential localization of the Drosophila and human enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15929–15940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam R, Nakamura M, Scott H, Repnikova E, Carnahan M, Pandey D, Caster C, Khan S, Zimmermann T, Zoran MJ, Panin VM. The role of Drosophila cytidine monophosphate-sialic Acid synthetase in the nervous system. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12306–12315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5220-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cime-Castillo J, Delannoy P, Mendoza-Hernandez G, Monroy-Martinez V, Harduin-Lepers A, Lanz-Mendoza H, de Hernandez-Hernandez FL, Zenteno E, Cabello-Gutierrez C, Ruiz-Ordaz BH. Sialic acid expression in the mosquito Aedes aegypti and its possible role in dengue virus-vector interactions. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:504187. doi: 10.1155/2015/504187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panin VM, Shao L, Lei L, Moloney DJ, Irvine KD, Haltiwanger RS. Notch ligands are substrates for protein O-fucosyltransferase-1 and Fringe. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29945–29952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherbas L, Moss R, Cherbas P. Transformation techniques for Drosophila cell lines. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:161–179. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60912-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brand AH, Manoukian AS, Perrimon N. Ectopic expression in Drosophila. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;44:635–654. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomiya N, Ailor E, Lawrence SM, Betenbaugh MJ, Lee YC. Determination of nucleotides and sugar nucleotides involved in protein glycosylation by high-performance anion-exchange chromatography: sugar nucleotide contents in cultured insect cells and mammalian cells. Anal Biochem. 2001;293:129–137. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyalin D, Koles K, Roosendaal SD, Repnikova E, Van Wechel L, Panin VM. The twisted gene encodes Drosophila protein O-mannosyltransferase 2 and genetically interacts with the rotated abdomen gene encoding Drosophila protein O-mannosyltransferase 1. Genetics. 2006;172:343–353. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.049650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Repnikova E, Koles K, Nakamura M, Pitts J, Li H, Ambavane A, Zoran MJ, Panin VM. Sialyltransferase regulates nervous system function in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2010;30:6466–6476. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5253-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llopis J, McCaffery JM, Miyawaki A, Farquhar MG, Tsien RY. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6803–6808. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paroutis P, Touret N, Grinstein S. The pH of the secretory pathway: measurement, determinants, and regulation. Physiology (Bethesda) 2004;19:207–215. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00005.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kean EL, Roseman S. The sialic acids. X Purification and properties of cytidine 5′-monophosphosialic acid synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:5643–5650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizanur RM, Pohl NL. Bacterial CMP-sialic acid synthetases: production, properties, and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;80:757–765. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1643-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kean EL. Sialic acid activation. Glycobiology. 1991;1:441–447. doi: 10.1093/glycob/1.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banda K, Gregg CJ, Chow R, Varki NM, Varki A. Metabolism of vertebrate amino sugars with N-glycolyl groups: mechanisms underlying gastrointestinal incorporation of the non-human sialic acid xeno-autoantigen N-glycolylneuraminic acid. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28852–28864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.364182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou HH, Takematsu H, Diaz S, Iber J, Nickerson E, Wright KL, Muchmore EA, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Varki A. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irie A, Koyama S, Kozutsumi Y, Kawasaki T, Suzuki A. The molecular basis for the absence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15866–15871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue S, Kitajima K. KDN (deaminated neuraminic acid): dreamful past and exciting future of the newest member of the sialic acid family. Glycoconj J. 2006;23:277–290. doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-6484-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raetz CR. Biochemistry of endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Neill MA, Ishii T, Albersheim P, Darvill AG. Rhamnogalacturonan II: structure and function of a borate cross-linked cell wall pectic polysaccharide. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:109–139. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higa HH, Paulson JC. Sialylation of glycoprotein oligosaccharides with N-acetyl-, N-glycolyl-, and N-O-diacetylneuraminic acids. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:8838–8849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Romani AM. Cellular magnesium homeostasis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;512:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosimann SC, Gilbert M, Dombroswki D, To R, Wakarchuk W, Strynadka NC. Structure of a sialic acid-activating synthetase, CMP-acylneuraminate synthetase in the presence and absence of CDP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8190–8196. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krapp S, Munster-Kuhnel AK, Kaiser JT, Huber R, Tiralongo J, Gerardy-Schahn R, Jacob U. The crystal structure of murine CMP-5-N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase. J Mol Biol. 2003;334:625–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horsfall LE, Nelson A, Berry A. Identification and characterization of important residues in the catalytic mechanism of CMP-Neu5Ac synthetase from Neisseria meningitidis. FEBS J. 2010;277:2779–2790. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rempoulakis P, Afshar N, Osorio B, Barajas-Aceves M, Szular J, Ahmad S, Dammalage T, Tomas US, Nemny-Lavy E, Salomon M, Vreysen MJ, Nestel D, Missirlis F. Conserved metallomics in two insect families evolving separately for a hundred million years. Biometals. 2014;27:1323–1335. doi: 10.1007/s10534-014-9793-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pham DQ, Winzerling JJ. Insect ferritins: Typical or atypical? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:824–833. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dechen K, Richards CD, Lye JC, Hwang JE, Burke R. Compartmentalized zinc deficiency and toxicities caused by ZnT and Zip gene over expression result in specific phenotypes in Drosophila. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;60:23–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heyes DJ, Levy C, Lafite P, Roberts IS, Goldrick M, Stachulski AV, Rossington SB, Stanford D, Rigby SE, Scrutton NS, Leys D. Structure-based mechanism of CMP-2-keto-3-deoxymanno-octulonic acid synthetase: convergent evolution of a sugar-activating enzyme with DNA/RNA polymerases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:35514–35523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt H, Mesters JR, Wu J, Woodard RW, Hilgenfeld R, Mamat U. Evidence for a two-metal-ion mechanism in the cytidyltransferase KdsB, an enzyme involved in lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schauer R, Haverkamp J, Ehrlich K. Isolation and characterization of acylneuraminate cytidylyltransferase from frog liver. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1980;361:641–648. doi: 10.1515/bchm2.1980.361.1.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Eijnden DH, Meems L, Roukema PA. The regional distribution of cytidine 5′-monophospho-N-acetyl-neuraminic acid synthetase in calf brain. J Neurochem. 1972;19:1649–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb06210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Dijk W, Ferwerda W, van den Eijnden DH. Subcellular and regional distribution of CMP-N-acetylneuraminic acid synthetase in the calf kidney. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973;315:162–175. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(73)90139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koles K, Lim JM, Aoki K, Porterfield M, Tiemeyer M, Wells L, Panin V. Identification of N-glycosylated proteins from the central nervous system of Drosophila melanogaster. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1388–1403. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aoki K, Perlman M, Lim JM, Cantu R, Wells L, Tiemeyer M. Dynamic developmental elaboration of N-linked glycan complexity in the Drosophila melanogaster embryo. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9127–9142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606711200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koles K, Repnikova E, Pavlova G, Korochkin LI, Panin VM. Sialylation in protostomes: a perspective from Drosophila genetics and biochemistry. Glycoconj J. 2009;26:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakata D, Munster AK, Gerardy-Schahn R, Aoki N, Matsuda T, Kitajima K. Molecular cloning of a unique CMP-sialic acid synthetase that effectively utilizes both deaminoneuraminic acid (KDN) and N-acetylneuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) as substrates. Glycobiology. 2001;11:685–692. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.8.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura N, Rabouille C, Watson R, Nilsson T, Hui N, Slusarewicz P, Kreis TE, Warren G. Characterization of a cis-Golgi matrix protein, GM130. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1715–1726. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.