Abstract

Prenatal exposure to excess androgen may result in impaired adult fertility in a variety of mammalian species. However, little is known about what feedback mechanisms regulate gonadotropin secretion during early gestation and how they respond to excess T exposure. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of exogenous exposure to T on key genes that regulate gonadotropin and GnRH secretion in fetal male lambs as compared with female cohorts. We found that biweekly maternal testosterone propionate (100 mg) treatment administered from day 30 to day 58 of gestation acutely decreased (P < .05) serum LH concentrations and reduced the expression of gonadotropin subunit mRNA in both sexes and the levels of GnRH receptor mRNA in males. These results are consistent with enhanced negative feedback at the level of the pituitary and were accompanied by reduced mRNA levels for testicular steroidogenic enzymes, suggesting that Leydig cell function was also suppressed. The expression of kisspeptin 1 mRNA, a key regulator of GnRH neurons, was significantly greater (P < .01) in control females than in males and reduced (P < .001) in females by T exposure, indicating that hypothalamic regulation of gonadotropin secretion was also affected by androgen exposure. Although endocrine homeostasis was reestablished 2 weeks after maternal testosterone propionate treatment ceased, additional differences in the gene expression of GnRH, estrogen receptor-β, and kisspeptin receptor (G protein coupled receptor 54) emerged between the treatment cohorts. These changes suggest the normal trajectory of hypothalamic-pituitary axis development was disrupted, which may, in turn, contribute to negative effects on fertility later in life.

Effects of T exposure initiated during fetal development lead to permanent organizational changes in external genital anatomy, brain structure, and neuroendocrine function that direct development of the male phenotype. Testicular androgen production starts in the male sheep fetus around gestational day (GD) 30, peaks around GD 70 and declines after GD 110 (1). This period of elevated circulating T is believed to encompass the broad limits of the critical period for sexual differentiation of reproductive anatomical dimorphism and function (2). Within this time frame, various sexually dimorphic traits have different individual periods of susceptibility to T and its metabolites. For example, the critical period for the ovine sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area, which is 2 times larger in male sheep than in females, occurs between GD 60 and GD 90 and follows the masculinization of the external genitalia, which occurs earlier between GD 30 and GD 60 (3). Both are androgen receptor dependent (4). Urination postures and sexual behaviors are sexually dimorphic and masculinized by T between GD 50 and GD 80 (5). In contrast, the neural mechanisms that time puberty and control the LH surge require exposure to T throughout the broader period and differ in their sensitivity to DHT, such that masculinization of puberty is androgen dependent, and defeminization of the LH surge appears to require the actions of both androgen and estrogens (2, 6).

Given the critical role played by steroid hormones in sexual development and reproductive function, it is not surprising that individuals affected by androgen excess disorders such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) often face immense challenges to their fertility (7). Females are particularly vulnerable to excess exposure from endogenous and exogenous androgens during the critical period, which can lead to genital virilization, impaired fertility, polycystic ovaries, masculinized sexual behavior, and altered metabolism (7, 8). Infertility is also one of the clinical features of CAH in male patients (7, 9). Studies in sheep demonstrate that when male fetuses are exposed to exogenous androgens during early gestation, the active hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis compensates by adjusting LH secretion and T synthesis to restore homeostasis to the endocrine milieu (4, 10). However, there appears to be a point at which feedback compensation during development can be pushed too far, resulting in hormone imbalances that can lead to impaired reproductive function that could negatively impact fertility. In various animal models, excess androgen exposure during male sexual differentiation is reported to alter testicular size, T concentration, seminiferous tubule size and function, germ cell number, sperm count, and motility (11–15). These adverse effects of prenatal T excess are initiated early in gestation, and by midgestation Leydig cell distribution is disturbed, expression of the Sertoli cell markers inhibin βA subunit and Wt1 is enhanced, and the expression of the germ cell marker homeobox gene POU5F1 is reduced (10).

Another target of potentially deleterious effects of excess fetal T may be the hypothalamus-pituitary gland axis. Fetal T normally programs the hypothalamus to have a masculine tonic secretory pattern of GnRH release in contrast to the cyclic pattern observed in females. Excess prenatal androgen exposure impairs cyclic GnRH release in females and masculinizes synaptic inputs to GnRH neurons (16, 17). There is also evidence in male sheep that excess prenatal androgen alters LH pulse characteristics, which suggests changes in the pattern of GnRH release from the hypothalamus (18). In adults, GnRH release is regulated by a subpopulation of neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus that coexpresses kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin (KNDy; ie, KNDy neurons). KNDy neurons are also thought to comprise a critical component of the circuitry responsible for generating GnRH and LH pulses through reciprocal autoregulatory connections (19, 20). Steroids are believed to exert feedback effects on GnRH neurons indirectly through kisspeptin neurons, although evidence exists that estrogen receptor-β (ESR2) is expressed in GnRH neurons and may play a role in GnRH gene expression and secretion (21). It is not known whether these feedback circuits are active in the ovine fetus and, if so, how early they become functional. The HPG axis in sheep differentiates and functions during fetal life. By midgestation, serum LH secretion in the fetal lamb is pulsatile (22) and can be stimulated by exogenous GnRH (23, 24). The pattern of gonadotropin secretion in the sheep fetus and their response to exogenous GnRH exhibits distinct sex differences (25, 26). Serum levels of both LH and FSH are higher in the female early in gestation and in both sexes peak around GD 110 and then fall progressively until term (26). Fetal castration demonstrates that prior to GD 130 the GnRH pulse generator is inhibited by the testis, but not the ovaries, whereas after GD 130 the pulse generator is inhibited by extragonadal factors (27).

It can be inferred from these studies that by midgestation LH secretion is regulated by pulsatile GnRH secretion from the fetal hypothalamus. However, it is not known whether KNDy neurons regulate GnRH pulsatility and steroid-negative feedback in the ovine fetus. The objective of this study was to determine the effect of exogenous exposure to T during the initial phase of the critical period for sexual differentiation on key genes that regulate gonadotropin and GnRH secretion in fetal male lambs compared with female cohorts. We hypothesized that exposure to excess T would suppress the fetal HPG axis and reduce developmental gene expression in the brain and pituitary that could lead to permanent (persistent) adverse changes in HPG function and ultimately impair male fertility.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

These studies were conducted in accordance with the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon State University.

Polypay ewes (n = 30) in their second breeding season underwent estrous cycle synchronization with intravaginal progesterone pessaries and prostaglandin F2α injections, as previously described (28), to allow for accurate calculation of gestational time points. Pregnant ewes were assigned randomly to control and treatment groups and received biweekly im injections of either control (C) corn oil vehicle or 100 mg testosterone propionate (TP; Steraloids) in 2 mL corn oil from GD 30 to GD 58. Fetuses were delivered either 24 hours after the last injection on GD59 or approximately 2 weeks after the last injection on GD 75. Deliveries were performed surgically under general anesthesia as described previously (28). The number and sexes of fetuses at each gestational age were as follows: GD 59; six C males, three C females, three T males, and six T females; and GD 75: four C males, three C females, four T males, and five T females. Fetal measures included body weight, brain weight, gonadal weight, adrenal weight, crown-rump length, and the ratio of anogenital distance to anoumbilical distance, a measure of external genital masculinization. The characteristics of the fetuses used in this study are presented in Supplemental Table 1, which shows that maternal androgen treatment effectively masculinized the genitalia of exposed female fetuses but had no effect on linear growth or body, gonad, and brain weights. Umbilical artery blood was sampled before the fetuses were exsanguinated, weighed, and measured.

Tissue collection

One fetal testis and half of the fetal anterior pituitary were immediately snap frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. The brain was bisected sagittally and half was used to dissect out the medial preoptic area (MPOA) and medial basal hypothalamus (MBH) using surface landmarks. Specifically, the hemisected brain was placed with the medial surface facing up, and the MPOA was obtained by making cuts rostral and caudal to the optic chiasm and extending from the base of the brain dorsally to the level of the anterior commissure. The MBH extended from the caudal optic chiasm cut to a cut made rostral to the mammillary bodies and limited dorsally by a horizontal cut extending caudally from the MPOA dissection. Fresh brain tissues were snap frozen and stored at −80°C.

Fetal sheep sex genotyping

Genetic sex was determined by PCR genotyping using fetal frontal cortex DNA extract (RED Extract-N-Amp kit; Sigma-Aldrich), ovine SRY primers (forward primer: 5′-CCGGGCTATAAATATCGACC-3′; reverse primer: 5′-GAGCGGCTTAATTGGCTTTC-3′; amplicon 173 bp) design based on the ovine SRY sequence (GenBank accession number Z30265) and ovine GADPH primers (Supplemental Table 2, 146 bp). PCR was run using Platinum PCR Supermix (Life Technologies) and the following program: 95°C for 3 minutes, 95°C for 30 seconds, 53°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 40 seconds (40 cycles) and 4°C. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel and visualized using ethidium bromide.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using an RNAqueous-4PCR kit (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. RNA sample concentration and purity was then determined using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Electrophoresis was performed to verify the integrity of the RNA. RNA (250 ng) was reverse transcribed to cDNA using oligodeoxythymidine primers with the Superscript III first-strand system (Invitrogen). Real-time PCRs were run in triplicate for each sample using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Invitrogen). Primer sets (Supplemental Table 2) for ovine genes were specifically designed to cross exon junctions using Clone Manager software version 8 (Sci-Ed Software). Reactions were run on the QuantStudio 7 Flex real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). The primer efficiencies were 87% or greater for all primer pairs and all melting curves showed a single peak. Quantification of gene expression was performed by the relative standard curve method (29), normalized against the reference gene GAPDH and reported as the fold difference relative to the mean expression level in the tissue of pooled control-treated animals.

Hormone analysis

Serum steroids were measured by a RIA after extraction and column chromatography by the Endocrine Support Core at the Oregon National Primate Research Center. The sensitivity per tube for estradiol, T, and progesterone was 1, 5, and 5 pg, respectively. The intra- and interassay variations were less than 10%. Serum LH was measured as described previously (4) using NIDDK-oLH-I-4 standard. The intra- and interassay variations were less than 8% and the assay sensitivity was 120 μg/tube.

Statistics

Hormone concentrations and gene expression data were analyzed for sex and treatment effects by a two-way ANOVA. Data were log10 transformed when necessary to equalize variance among groups. Post hoc comparisons were made with a Fisher's least squares difference test when a significant interaction between major effects was found. The expression of the testicular genes was compared between control and treatment groups using the Student's t test. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM, with P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Maternal androgen administration increased serum T and estradiol concentrations and suppressed gonadotropin secretion and synthesis in GD 59 fetuses

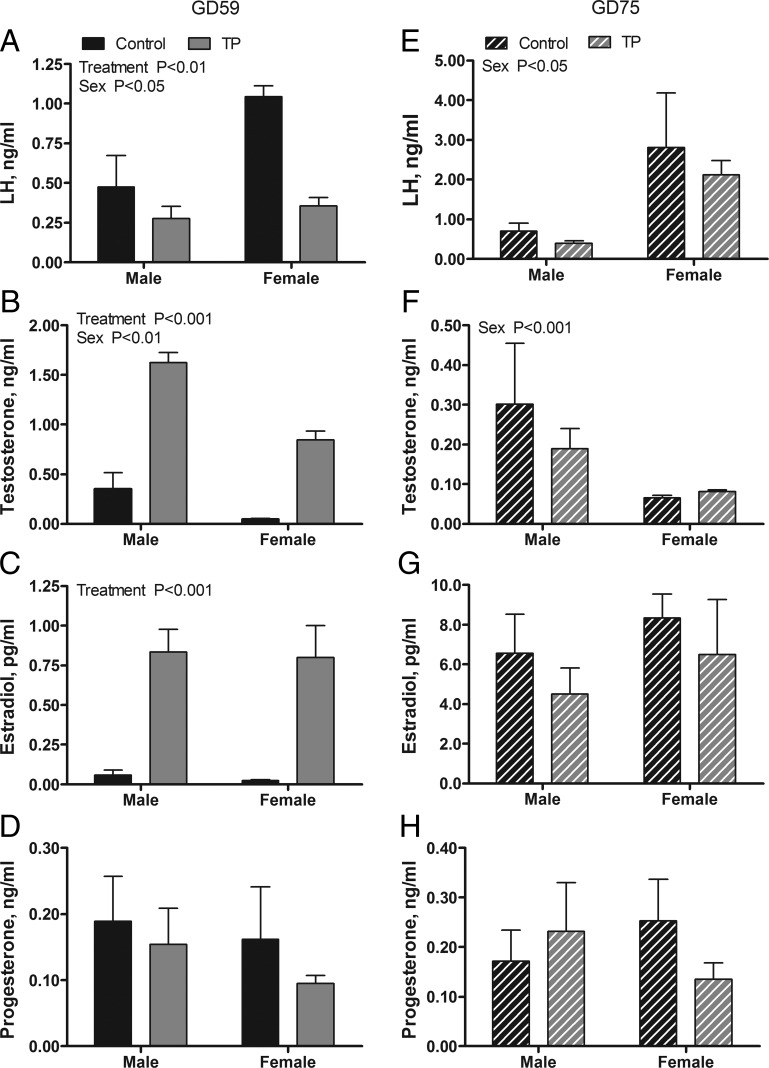

Fetal hormone levels in GD 59 fetuses immediately after 30 days of maternal androgen administration are presented in Figure 1, A–D. Limitations in the volume of serum available precluded measurement of both LH and steroid concentrations in all samples. Thus, LH is reported for only two of three C females and four of six C males. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of treatment on serum T (P < .001), estradiol (P < .001), and LH (P < .01) but not progesterone concentrations. Fetal T and estradiol were significantly elevated and LH was significantly suppressed in the T vs C cohorts. A significant main effect of sex was observed for T (P < .01) and LH (P < .05) but not for estradiol or progesterone. Serum T was higher in males than in females, whereas LH was greater in females than in males. Two weeks after maternal androgen treatment was stopped, serum LH, T, and estradiol concentrations were normalized between treatment cohorts of GD 75 fetuses (Figure 1, E–G). A two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of sex for LH (P < .01) and T (P < .01) but no effect of treatment. Males exhibited higher T and lower LH concentrations than females. No treatment effects or sex differences were observed on the serum levels of progesterone at GD 75 (Figure 1H).

Figure 1.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on serum LH and steroid concentrations in GD 59 (A–D) and GD 75 (E–H) ovine fetuses. Data for each age (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA.

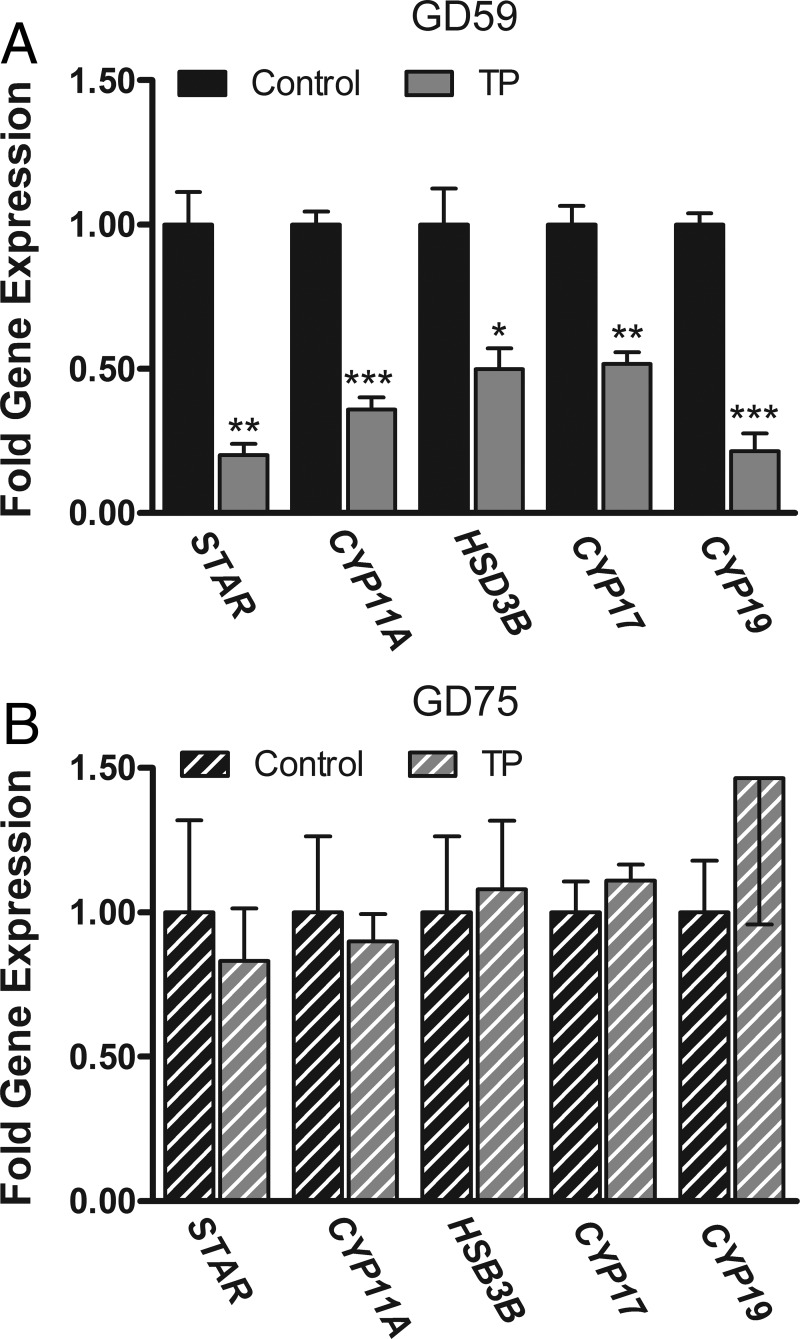

Maternal androgen administration suppressed fetal testicular steroidogenic enzyme mRNA expression in GD 59 fetuses

Figure 2A illustrates that maternal androgen treatment globally down-regulates the expression of steroidogenic enzyme mRNA in the fetal testes. Specifically there was a significant (P < .05) decrease in the mRNA expression of steroid acute regulatory protein (STAR), cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A), cytochrome P450 17α hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17), 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/δ4-δ5 isomerase (HSD3B), and aromatase (CYP19) in the T vs C fetuses. Maternal TP treatment had no effect on the expression of LH receptor (LHR), FSH receptor (FSHR), anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), inhibin-βA subunit (INHBA), androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor-α (ESR1) and ESR2 in the GD 59 testis (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). The effects on the testis were resolved 2 weeks after maternal androgen treatment was stopped. Expression levels of testicular steroidogenic genes were comparable between GD 75 fetal treatment cohorts (Figure 2B). No significant treatment effects were observed on gene expression of LHR, FSHR, AMH, INHBA, AR, and ESR1 in GD75 testis (Supplemental Figure 1, C and D). However, ESR2 mRNA levels in the testis were significantly (P < .05) lower in T males (0.68- ± 0.06-fold expression; mean ± SEM) relative to C males (1.0- ± 0.03-fold expression, Supplemental Figure 1C).

Figure 2.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on steroidogenic gene expression in the testes of GD 59 (A) and GD 75 (B) ovine fetuses. Data (mean ±SEM) were analyzed by a Student's t test. *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001, control vs TP treatments.

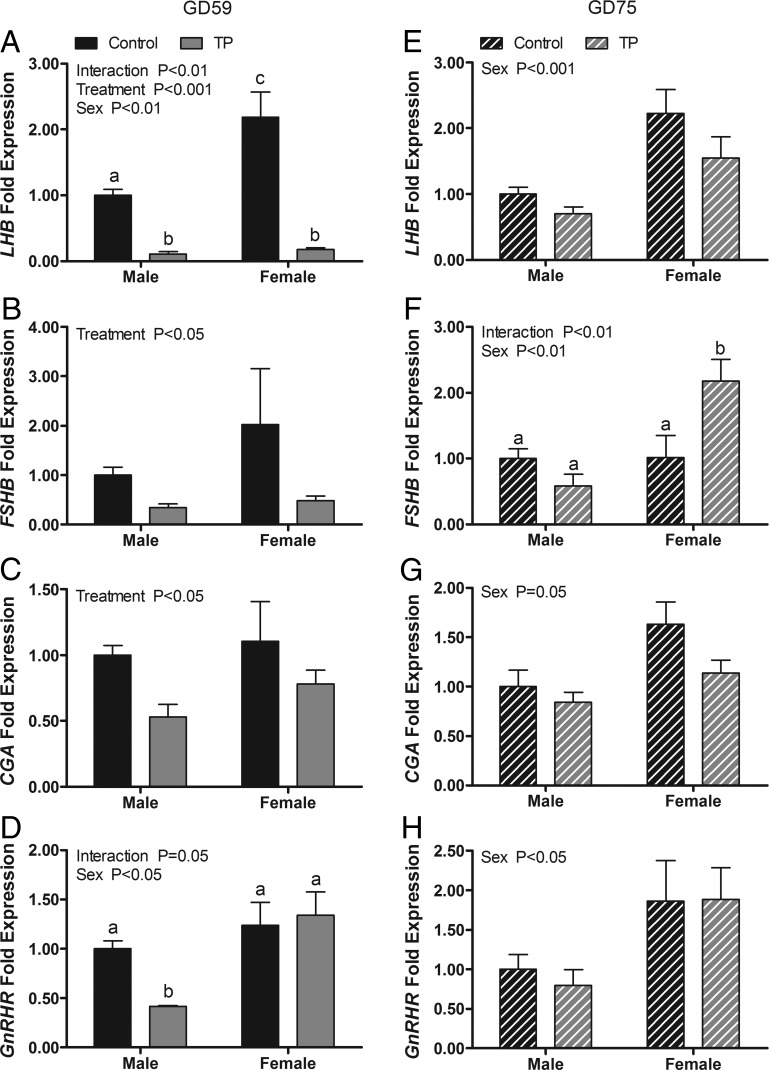

Maternal androgen administration suppressed gonadotropin subunit and GnRHR gene expression in fetal pituitaries in GD 59 fetuses

The effects of maternal androgen administration on gonadotropin subunit and GnRHR gene expression in the GD 59 fetal pituitary are shown in Figure 3, A–D. A two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of treatment on expression of mRNAs for LH-β subunit (LHB; P < .001), FSH-β subunit (FSHB; P = .05), and the common glycoprotein-α subunit (CGA; P < .05). Maternal TP treatment suppressed the mRNA expression of all three subunits, providing evidence that the fetal pituitary responds to exogenous T in the expected negative feedback manner. A significant main effect of sex (P < .01) and a significant treatment × sex interaction (P < .01) were observed also for LHB. LHB mRNA expression was significantly greater in C females than in C males and significantly reduced (P < .001) by T exposure in both sexes. There were significant main effects of sex (P < .05) and a significant treatment × sex interaction (P < .05) on the expression of GnRHR. Post hoc comparisons revealed that GnRHR mRNA in males was significantly lower (P < .05) than in all other groups. Although expression levels of LHB, CGA, and GnRHR mRNA did not differ significantly between treatments 2 weeks after maternal androgen treatment ceased, all three exhibited a significant sex difference (P < .05, Figure 3, E, G, and H). For all genes, mRNA levels were greater in females than in males. There was a significant main effect of sex (P < .01) for FSHB mRNA expression and a significant treatment × sex interaction (P < .01). Post hoc comparisons indicated that FSHB expression was significantly (P < .05) greater in T females than all other groups.

Figure 3.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on gonadotropin subunit and GnRHR gene expression in the pituitary of GD 59 (A–D) and GD 75 (E–H) ovine fetuses. Data (means ±SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bars with different superscripts differ significantly (P < .05).

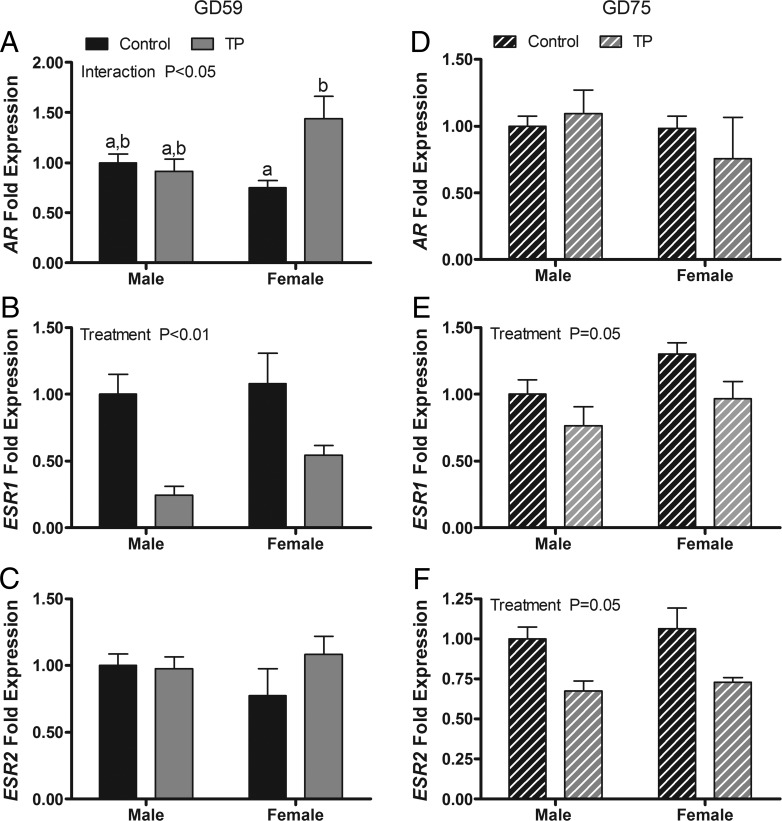

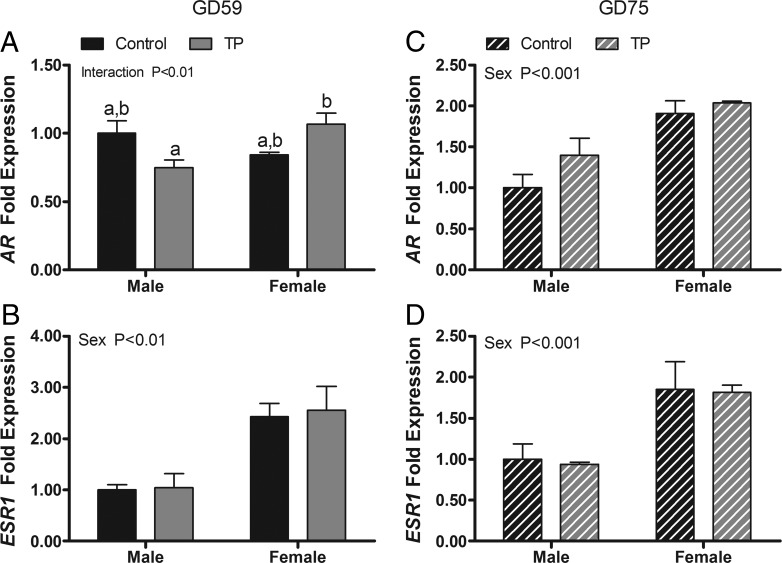

Effect of maternal androgen administration on pituitary AR and estrogen receptor mRNA expression.

The expression of AR and ESR1, but not ESR2, was altered by maternal T administration (Figure 4, A–C). A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of treatment on expression of ESR1 mRNA (P < .001) and a treatment × sex interaction for expression of AR mRNA (P < .05). Maternal TP treatment suppressed ESR1 expression in both sexes and elevated AR mRNA expression in females. Two weeks after maternal treatments ceased, residual suppression (P < .05) of ESR1 by T exposure was evident and a significant (P < .05) main effect of treatment on ESR2 newly appeared (Figure 4, D–F).

Figure 4.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on gene expression in the pituitary of GD 59 (A–C) and GD 75 (D–F) ovine fetuses. Data (mean ±SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bars with different superscripts are significantly different (P < .05).

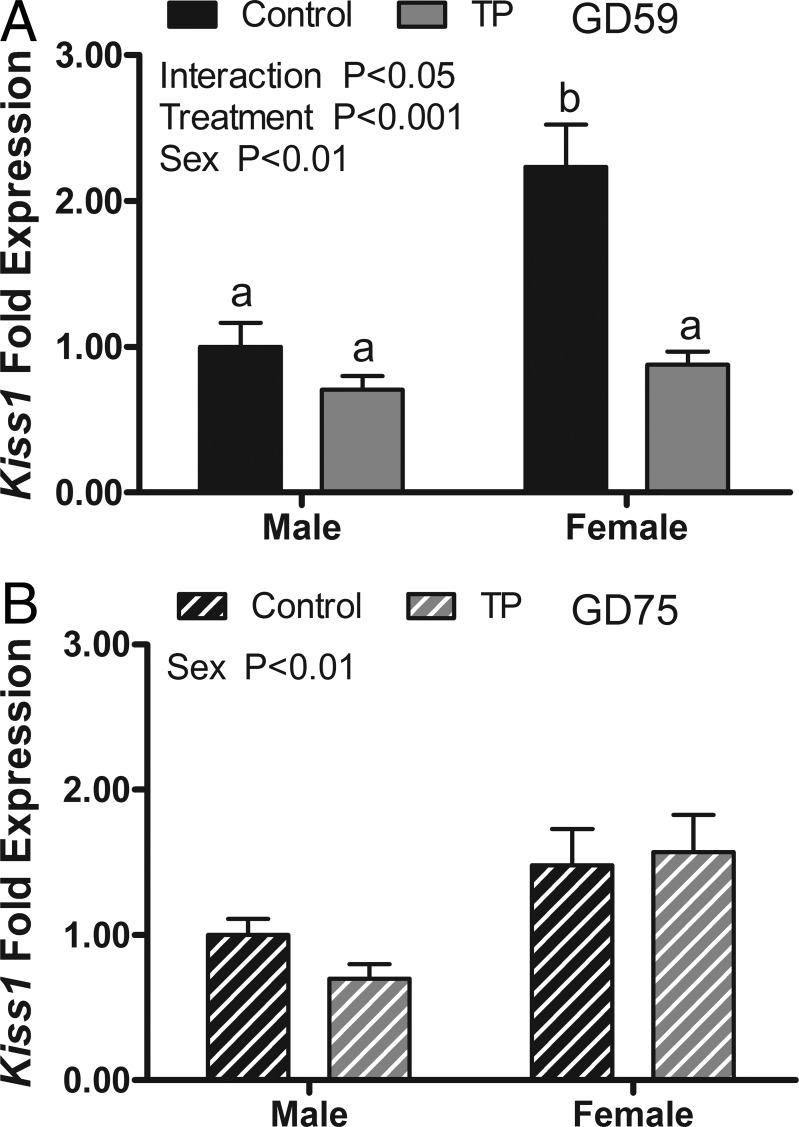

Effect of maternal androgen administration on kisspeptin (Kiss1) mRNA and other hypothalamic regulators of gonadotropins

Figure 5A shows the results of T exposure on Kiss1 mRNA expression in the MBH of GD 59 fetuses. A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of sex (P < .05) and maternal androgen treatment (P < .001) and a significant treatment × sex interaction (P < .01). Post hoc comparisons found that Kiss1 expression was significantly higher in the control females than in the control males. Maternal androgen treatment suppressed Kiss1 expression in the females to levels that were equivalent to C and T males. Maternal androgen treatment did not affect the expression of kisspeptin receptor (G protein-coupled receptor 54 [GPR54]), tachykinin 3/neurokinin B [TAC3]), TAC receptor 3 (TACR3), prodynorphin (PDYN), opiate-κ1 receptor (OPKR1) mRNAs in the MBH (Supplemental Figure 2). The expression of ESR1 and AR mRNA were not affected by treatment; however, ESR1 expression was significantly (P < .01) higher in the MBH of females than males, and AR expression was greater in T females than in T males (Figure 6, A and B). Two weeks after maternal androgen treatments had ceased, there was no longer a treatment effect on Kiss1 mRNA in GD 75 fetuses, but there was a significant sex difference (females > males; P < .05, Figure 5B). No differences between GD 75 treatment cohorts were observed for GPR54, TAC3, TACR3, PDYN, and OPKR1, but the expression of TACR3 and OPKR1 was significantly (P < .001) greater in males than in females at this age (Supplemental Figure 2). The expression of AR and ESR1 mRNAs at GD 75 was also unaltered by treatment and significantly (P < .001) greater in females than in males (Figure 6, C and D).

Figure 5.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on Kiss1 gene expression in the medial basal hypothalamus of GD 59 (A) and GD 75 (B) ovine fetuses. Data (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bars with different superscripts are significantly different (P < .05).

Figure 6.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on AR and ESR1 gene expression in the MBH of GD 59 (A and B) and GD 75 (C and D) ovine fetuses. Data (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bars with different superscripts are significantly different (P < .05).

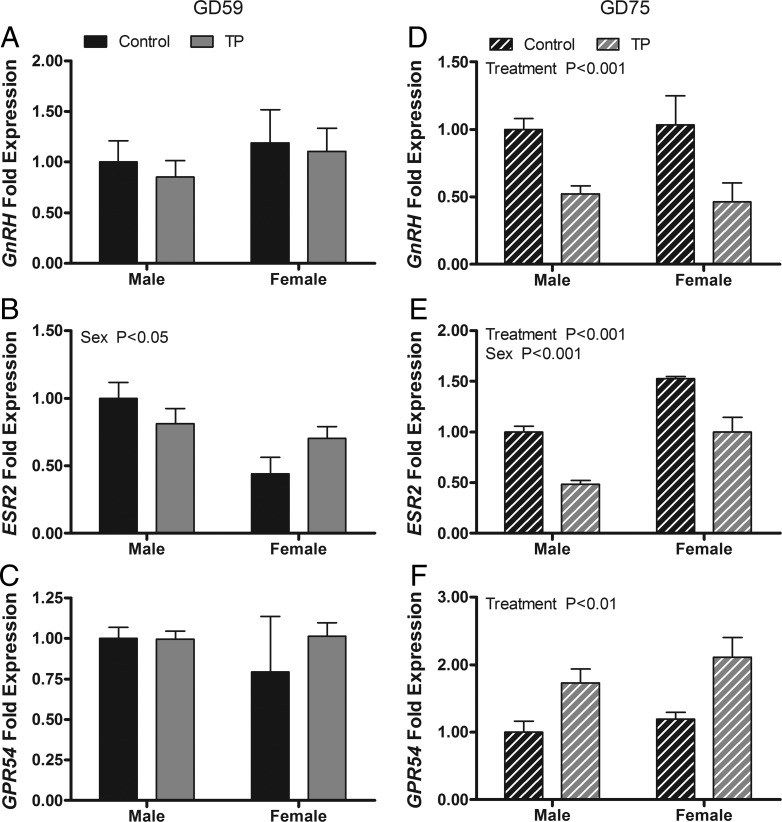

Effect of maternal androgen administration on GnRH mRNA and other preoptic area regulators of gonadotropins

Maternal androgen treatment did not affect the expression of GnRH, ESR2, or GPR54 mRNAs in the MPOA of GD 59 fetuses (Figure 7, A–C). However, the expression of ESR2 was significantly greater (P < .05) in males than in females. In GD 75 fetuses (Figure 7, D–F), significant treatment effects were observed for the expression of GnRH (P < .001), ESR2 (P < .001), and GPR54 (P < .01). GnRH and ESR2 mRNA expression was lower in the T cohort than in controls; GPR54 was higher in the T cohort. ESR2 mRNA expression was higher (P < .001) in females than in males.

Figure 7.

Effects of twice-weekly maternal TP (100 mg/injection) and control oil vehicle (2 mL) injections from GD 30 to GD 58 on gene expression in the medial preoptic area of GD 59 (A–C) and GD 75 (D–F) ovine fetuses. Data (mean ± SEM) were analyzed by a two-way ANOVA. Bars with different superscripts are significantly different (P < .05).

Discussion

Findings from this study demonstrated that maternal TP treatment, which exposed fetuses to excess T during the onset of the critical period, decreased serum LH concentrations and reduced the expression of gonadotropin subunit mRNA in both sexes and the levels of GnRHR mRNA in males. These results are consistent with enhanced negative feedback at the level of the pituitary and were accompanied by reduced mRNA levels for components of the testicular steroidogenic pathway, suggesting that Leydig cell function was also suppressed in males. No effects were noted on the expression of other testicular genes measured, indicating that other aspects of Leydig and Sertoli cell function were not altered. The expression of Kiss1 mRNA, a key regulator of GnRH neurons, was reduced in females by T exposure, indicating that hypothalamic regulation of gonadotropin secretion is also affected. The effects of excess T exposure on hormone levels and HPG gene expression were mostly resolved 2 weeks after maternal treatments ended, suggesting that feedback homeostasis was restored. Differences emerged between control and T-exposed fetuses in the abundance of GnRH and GPR54 mRNA in the preoptic area and ESR2 mRNA in pituitary, testes, and preoptic area. These results demonstrate that excess exposure to T suppresses the fetal HPG axis much earlier than examined previously and alters the trajectory of developmental gene expression in the hypothalamus and pituitary of both males and females (10, 12, 30–32). However, it should be stressed that mRNA levels do not always translate into equivalent changes in protein levels and secretory activity. Thus, further studies will be needed to determine whether the changes in mRNA levels observed in GD 75 fetuses are biologically significant and can produce permanent effects on reproductive function.

Previous reports show that during normal development, serum LH concentrations are higher in female than in male lamb fetuses between GD 55 and GD 100 (26, 33), whereas serum T levels are significantly higher in males than in females (28, 34–36). Castration causes an increase in LH pulse frequency and amplitude in midgestation males but has no effect in females (27), indicating the GnRH pulse generator is active and being suppressed by the fetal testes but not the ovaries. Indeed, maternal treatment with the AR antagonist flutamide significantly increases serum LH and T secretion in midgestation males, whereas treatment with T or DHT suppresses LH secretion and basal testicular T production (4, 10). The present study confirms that pituitary negative-feedback mechanisms are in place early in the critical period for brain differentiation in sheep (4, 26). We found an inverse relationship between LH and T in both GD 59 and GD 75 fetuses. LH levels are higher in females than in males, and T levels are greater in males than in females. At GD 59, maternal TP treatment elevated T levels in fetal serum and suppressed LH levels. By GD 75, the effects of exogenous T had mostly dissipated, but LH levels were higher in females than in males and T levels were greater in males than in females. Changes in LHB mRNA that reflected the differences in LH between the sexes and treatment groups were observed. Pituitary steroid receptor mRNA expression was not altered with the exception of ESR1, which was reduced. Most evidence suggests that suppression of gonadotropin synthesis by steroids is mediated indirectly via decreased hypothalamic GnRH secretion or altered pituitary responsiveness to GnRH (37–39). Our observation that GnRHR mRNA expression is reduced in T-exposed male supports this concept. The decrease in pituitary ESR1 mRNA may relate to another aspect of pituitary development or function regulated by estrogens and underscores a limitation of using quantitative PCR on a mixed population of pituitary cells.

We found that maternal TP treatment led to a general down-regulation of genes involved in T and estradiol production by the testis, which is likely due to decreased gonadotropin support. T treatment did not affect LHR mRNA levels, indicating that Leydig cell sensitivity to LH was not altered. These results suggest that in sheep, testicular androgen synthesis becomes dependent on LH as early as the end of the first trimester, soon after differentiation of the genitalia and onset of HPG axis functioning. A previous study found that maternal TP treatment starting at GD 62 not only suppresses serum LH and pituitary LHB mRNA expression but also alters Leydig cell distribution and decreases the steroidogenic capacity of fetal testes at GD 70 and GD 90 (10). Similar results were achieved by direct fetal injection of T, but not diethylstilbestrol, supporting a direct androgen effect. The same study found that Sertoli and germ cells were also affected when T administration started on GD 30. Other studies using sheep showed that the adverse effects of androgen exposure on testicular size, seminiferous tubule size and function, germ cell number, sperm count, and motility persist after birth in males; however, there is no general agreement on whether postnatal T increases, decreases, or remains unchanged (12–15, 40).

Maternal TP treatment suppressed FSHB mRNA in GD 59 fetuses, suggesting that fetal FSH, like LH, is sensitive to androgen-negative feedback. Unlike with LH, we did not observe sex differences in the expression of either FSHB or CGA mRNAs at GD 59. A sex difference in FSH levels and mRNA expression appears to emerge after GD 70, reflecting a difference in the maturation of fetal sheep gonadotrophs (4, 26, 41) and is evident in the present study in GD 75 fetuses. A recent report in females found that FSHB mRNA was increased at GD 65 and decreased at GD 90 after continuous maternal TP treatment, starting on GD 30, and presents evidence this may occur through paracrine changes in activin and inhibin signaling (30). The role of FSH in normal fetal testis development is not clear. A large part of fetal testis development involves Sertoli cell proliferation. The number of Sertoli cells in the adult testis is critically dependent on numbers that develop during gestation. The number of adult Sertoli cells, in turn, will determine adult testis size and sperm production because each Sertoli cell will support only a limited number of germ cells (42). Data from rats and mice indicate that proliferation of Sertoli cells during fetal and neonatal development is regulated largely by androgens, not FSH (43). The role of FSH in regulating Sertoli cell function or proliferation in nonrodent species is uncertain. Treatment of fetal lambs with octylphenol, an endocrine-disrupting chemical, reduces FSH and Sertoli cell numbers without significantly affecting LH levels, but a role for androgen was not assessed in this study and cannot be ruled out (44). We found no effect of maternal TP treatment on gene expression associated with Sertoli cell function including FSHR or INHBA, suggesting that excess androgen exposure neither enhances nor impairs fetal Sertoli cells in fetal ram lambs.

In the adult arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, kisspeptin is colocalized with two other neuropeptides, neurokinin B ([NKB]/TAC3) and dynorphin (Dyn) in a cell population that is named KNDy neurons (45). KNDy neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus form a reciprocally interconnected circuit that is believed to generate GnRH pulses and mediate steroid control over pulse frequency (19, 20). We found that the levels of Kiss1 mRNA in the medial basal hypothalamus of GD 59 fetuses were significantly higher in control females than in control males and significantly reduced by maternal TP treatment in females. In contrast, prenatal T exposure had no effect on the expression of any other component of this arcuate circuitry in GD 59 fetuses, including GPR54, TAC3, TACR3, PDYN, and OPKR1. Additionally, prenatal T exposure did not alter the expression of AR and ESR1 in the MBH. These results provide evidence that T may acutely regulate LH secretion in the ovine fetus in part through actions on kisspeptinergic neurons upstream of GnRH neurons. In a related study, Bellingham et al (46) found that hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA was significantly decreased in GD 110 ovine fetuses by maternal ingestion of a complex cocktail of environmental endocrine disruptors absorbed from sewage sludge used as pasture fertilizer. In adult sheep, the KNDy cell subpopulation of the arcuate is sexually dimorphic, exhibiting greater numbers of kisspeptin-, NKB/TAC3-, Dyn-, and progesterone-positive cells in adult females than in males (47). Prenatal T treatment decreases the number of NKB/TAC3, Dyn, and progesterone neurons but not the number of kisspeptin neurons in the female arcuate nucleus, leading to a potential mechanism by which progesterone sensitivity is reduced. Thus, although T acutely regulates Kiss1 expression prenatally as shown in the present study, it is probably not solely responsible for determining the fate of kisspeptin neurons that ultimately establishes adult sex differences in steroid feedback on the hypothalamus.

Androgens have also been shown to down-regulate hypothalamic Kiss1 mRNA in embryonic mice as well as adult rodents and monkeys (48–51). In contrast to our results in fetal sheep, T has been found to also reduce the expression of GPR54/Kiss1 receptor, TAC2/NKB, and PDYN in rodents (51, 52). The difference between fetal sheep and adult rodents may reflect developmental or species differences. Recent studies in mice found that the arcuate kisspeptin/GnRH neuronal circuitry is established and operative before birth (49, 53, 54). Arcuate kisspeptin neurons coexpress AR and ESR1 in fetal mouse brain, indicating that gonadal steroids could impact their development and/or synaptic activity (53, 54). The present study demonstrates that androgen feedback regulation through kisspeptin may occur as early as GD 59 in sheep, soon after the vascular connections between the hypothalamus and pituitary are established and subsequent to the masculinization of the internal and external genitalia (55, 56). Further research is needed to establish at what age functional neural circuits develop between kisspeptin and GnRH neurons in the fetal sheep and determine their role in reproductive development.

Although the prevailing doctrine is that negative feedback is indirect and conveyed through presynaptic afferents from Kiss 1 neurons that activate GPR54 in GnRH neurons (57), another body of evidence documents the presence of functional estrogen receptors in GnRH neurons (21). The predominant estrogen receptor found in preoptic GnRH neurons is believed to be ESR2, which was first located in GnRH neurons in rats (58) and has subsequently been found in GnRH neurons in sheep (59). Furthermore, evidence exists that ESR2 contributes to the regulation of GnRH neuronal activity, gene expression, and pulsatile release (21). In the present experiment, maternal TP exposure did not alter the expression of GnRH, ESR2, or GPR54 in the MPOA of GD 59 ovine fetuses, in which the greatest numbers of GnRH neurons reside in adult and fetal sheep (60, 61). These results suggest that T does not acutely regulate synthesis of GnRH or alter the potential of preoptic neurons to respond to estrogens through ESR2 or kisspeptin through GPR54.

Our results show that pituitary and testes function had mostly returned to normal 2 weeks after maternal TP treatments were stopped. Serum hormone concentrations no longer differed between treatment groups, and gene expression of gonadotropin subunits and steroidogenic enzymes were also comparable between cohorts. Thus, the acute negative feedback effects of early excess T exposure resolved after maternal treatment ceased. Serum LH was significantly higher in GD 75 females than in males. Corresponding sex differences were observed in the expression of LHB, CGA, and GnRHR mRNAs, indicating that pituitary gonadotropin synthesis and GnRH responsiveness are regulated at least in part at the transcriptional. Kiss1 mRNA expression in MBH was also greater in females than in males, consistent with greater stimulatory drive to GnRH neurons. There was no sex difference in the expression of TAC3/NKB and PDYN, although there are almost twice the number NKB- and Dyn-positive cells in the arcuate nucleus of adults (47). However, both TACR3 and OKPR1 mRNA levels were higher in GD 75 females than in males. These results are intriguing because the current model in adults suggests that TAC3 and Dyn are synchronously released and drive pulsatile kisspeptin secretion at the synaptic level (20, 62). Thus, we speculate that the elevated mean levels of LH in GD 75 females compared with males could be due to the enhanced pulsatile release of kisspeptin and GnRH. Further studies are needed to identify the specific cell populations in which these molecules are regulated to unravel their roles.

Androgen exposure in utero induced changes in pituitary (ESR1 and ESR2), testis (ESR2), and preoptic (GnRH, ESR2, and GPR54) gene expression in GD 75 fetuses. These effects are difficult to reconcile with acute regulation of gonadotropin secretion in the fetus. However, they provide circumstantial evidence that disruption of hypothalamic and testicular gene expression by early prenatal T exposure may alter normal development of the reproductive axis and lead possibly to some of the consequences on sexual maturation and fertility observed later in life (18, 63, 64).

In summary, our results demonstrate that excess exposure of fetal sheep to T early in the critical period for sexual differentiation elicits acute negative feedback on gonadotropin secretion in both sexes and suppression of testicular steroidogenic gene expression in males. Coincident changes in hypothalamic Kiss1, pituitary gonadotropin subunits, and testicular steroidogenic gene expression indicate that homeostatic regulation is mediated at all levels of the HPG axis. Although endocrine homeostasis was reestablished after maternal TP treatment was ceased, changes in gene expression emerged that indicate the normal trajectory of HPG development was disrupted and could affect the timing of puberty and/or alter adult male fertility. These results provide insights into possible mechanisms and targets affected by clinical syndromes of inappropriate prenatal androgen exposure such as CAH or disrupted by exposure to environmental contaminants with endocrine actions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mary Meaker and the Oregon State University Sheep Center for supplying the healthy ewes bred for these studies and thank our work study students for helping with the care of our animals. We also acknowledge Dr Hernan Montilla and Oregon State University veterinary students for helping with the surgical delivery of fetuses. Hormone measurements performed by the Endocrine Technology and Support Core was supported by the Oregon National Primate Research Center Core.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01OD011047 (to C.E.R.) and Oregon National Primate Research Center Core Grant P51 OD011092 (to Endocrine Technology and Support Core).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AR

- androgen receptor

- C

- control

- CAH

- congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- CGA

- common glycoprotein-α subunit

- Dyn

- dynorphin

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor-α

- ESR2

- estrogen receptor-β

- FSHB

- FSH-β subunit

- FSHR

- FSH receptor

- GD

- gestational day

- GPR54

- G protein-coupled receptor 54

- HPG

- hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

- INHBA

- inhibin-βA subunit

- Kiss1

- kisspeptin

- KNDy

- kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin

- LHB

- LH-β subunit

- LHR

- LH receptor

- MBH

- medial basal hypothalamus

- MPOA

- medial preoptic area

- NKB

- neurokinin B

- OPKR1

- opiate-κ1 receptor

- PDYN

- prodynorphin

- TAC3

- tachykinin 3

- TACR3

- TAC receptor 3

- TP

- testosterone propionate.

References

- 1. Ford JJ, D'Occhio MJ. Differentiation of sexual behavior in cattle, sheep, and swine. J Anim Sci. 1989;67:1816–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wood RI, Foster DL. Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Rev Reprod. 1998;3:130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roselli CE, Estill C, Stadelman HL, Meaker M, Stormshak F. Separate critical periods exist for testosterone-induced differentiation of the brain and genitals in sheep. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2409–2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roselli CE, Reddy R, Estill C, et al. Prenatal influence of an androgen agonist and antagonist on the differentiation of the ovine sexually dimorphic nucleus in male and female lamb fetuses. Endocrinology. 2014;155:5000–5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke IJ, Scaramuzzi RJ, Short RV. Effects of testosterone implants in pregnant ewes on their female offspring. J Embryol Exp Morph. 1976;36:87–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jackson LM, Timmer KM, Foster DL. Sexual differentiation of the external genitalia and the timing of puberty in the presence of an antiandrogen in sheep. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4200–4208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reichman DE, White PC, New MI, Rosenwaks Z. Fertility in patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Padmanabhan V, Veiga-Lopez A. Sheep models of polycystic ovary syndrome phenotype. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;373:8–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sugino Y, Usui T, Okubo K, et al. Genotyping of congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency presenting as male infertility: case report and literature review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2006;23:377–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Connolly F, Rae MT, Bittner L, Hogg K, McNeilly AS, Duncan WC. Excess androgens in utero alters fetal testis development. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1921–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramezani Tehrani F, Noroozzadeh M, Zahediasl S, Ghasemi A, Piryaei A, Azizi F. Prenatal testosterone exposure worsen the reproductive performance of male rat at adulthood. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rojas-Garcia PP, Recabarren MP, Sarabia L, et al. Prenatal testosterone excess alters Sertoli and germ cell number and testicular FSH receptor expression in rams. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299:E998–E1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rojas-Garcia PP, Recabarren MP, Sir-Petermann T, et al. Altered testicular development as a consequence of increase number of Sertoli cell in male lambs exposed prenatally to excess testosterone. Endocrine. 2013;43:705–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Recabarren SE, Rojas-Garcia PP, Recabarren MP, et al. Prenatal testosterone excess reduces sperm count and motility. Endocrinology. 2008;149:6444–6448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bormann CL, Smith GD, Padmanabhan V, Lee TM. Prenatal testosterone and dihydrotestosterone exposure disrupts ovine testicular development. Reproduction. 2011;142:167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim SJ, Foster DL, Wood RI. Prenatal testosterone masculinizes synaptic input to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in sheep. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson LM, Mytinger A, Roberts EK, et al. Developmental programming: postnatal steroids complete prenatal steroid actions to differentially organize the GnRH surge mechanism and reproductive behavior in female sheep. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1612–1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Recabarren SE, Recabarren M, Rojas-Garcia PP, Cordero M, Reyes C, Sir-Petermann T. Prenatal exposure to androgen excess increases LH pulse amplitude during postnatal life in male sheep. Horm Metab Res. 2012;44:688–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goodman RL, Hileman SM, Nestor CC, et al. Kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and dynorphin act in the arcuate nucleus to control activity of the GnRH pulse generator in ewes. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4259–4269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wakabayashi Y, Nakada T, Murata K, et al. Neurokinin B and dynorphin A in kisspeptin neurons of the arcuate nucleus participate in generation of periodic oscillation of neural activity driving pulsatile gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion in the goat. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3124–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wolfe A, Wu S. Estrogen receptor-β in the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuron. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30:23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clark SJ, Ellis N, Styne DM, Gluckman PD, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus. XVII: demonstration of pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion by the fetal pituitary gland. Endocrinology. 1984;115:1774–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mueller PL, Sklar CA, Gluckman PD, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus. IX. Luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone response to luteinizing hormone-releasing factor in mid- and late gestation and in the neonate. Endocrinology. 1981;108:881–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brooks AN, Currie IS, Gibson F, Thomas GB. Neuroendocrine regulation of sheep fetuses. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1992;45:69–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matwijiw I, Faiman C. Control of gonadotropin secretion in the ovine fetus. II. A sex difference in pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion after castration. Endocrinology. 1989;124:1352–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sklar CA, Mueller PL, Gluckman PD, Kaplan SL, Rudolph AM, Grumbach MM. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus. VII. Circulating luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone in mid- and late gestation. Endocrinology. 1981;108:874–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mesiano S, Hart CS, Heyer BW, Kaplan SL, Grumbach MM. Hormone ontogeny in the ovine fetus. XXVI. A sex difference in the effect of castration on the hypothalamic-pituitary gonadotropin unit in the ovine fetus. Endocrinology. 1991;129:3073–3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reddy RC, Estill CT, Meaker M, Stormshak F, Roselli CE. Sex differences in expression of oestrogen receptor α but not androgen receptor mRNAs in the foetal lamb brain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2014;26:321–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larionov A, Krause A, Miller W. A standard curve based method for relative real time PCR data processing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:62–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Manikkam M, Thompson RC, Herkimer C, Welch KB, Flak J, Karsch FJ, Padmanabhan V. Developmental programming: impact of prenatal testosterone excess on pre- and postnatal gonadotropin regulation in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2008;78:648–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luense LJ, Veiga-Lopez A, Padmanabhan V, Christenson LK. Developmental programming: gestational testosterone treatment alters fetal ovarian gene expression. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4974–4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hogg K, McNeilly AS, Duncan WC. Prenatal androgen exposure leads to alterations in gene and protein expression in the ovine fetal ovary. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2048–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foster DL, Roach JF, Karsch FJ, Norton HW, Cook B, Nalbandov AV. Regulation of luteinizing hormone in the fetal and neonatal lamb. I. LH concentrations in blood and pituitary. Endocrinology. 1972;90:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sklar CA, Mueller PL, Gluckman PD, Kaplan SL, Rudolph AM, Grumbach MM. The ontogeny of gonadotropins and sex steroids in the sheep fetus. Pediatr Res. 1978;12(suppl):420. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Veiga-Lopez A, Steckler TL, Abbott DH, et al. Developmental programming: impact of excess prenatal testosterone on intra-uterine fetal endocrine milieu and growth in sheep. Biol Reprod. 2011;84:87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pomerantz DK, Nalbandov AV. Androgen levels in the sheep fetus during gestation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1975;149:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scully KM, Gleiberman AS, Lindzey J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Rosenfeld MG. Role of estrogen receptor-α in the anterior pituitary gland. Mol Endocrinol. 1997;11:674–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hara L, Curley M, Tedim Ferreira M, Cruickshanks L, Milne L, Smith LB. Pituitary androgen receptor signalling regulates prolactin but not gonadotrophins in the male mouse. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rispoli LA, Nett TM. Pituitary gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor: structure, distribution and regulation of expression. Anim Reprod Sci. 2005;88:57–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wilson PR, Tarttelin MF. Studies on sexual differentiation of sheep. I. Foetal and maternal modifications and post-natal plasma LH and testosterone content following androgenisation early in gestation. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1978;89:182–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brooks AN, Hagan DM, Sheng C, McNeilly AS, Sweeney T. Prenatal gonadotrophins in the sheep. Anim Reprod Sci. 1996;42:471–481. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Orth JM, Gunsalus GL, Lampis AA. Evidence from Sertoli cell-depleted rats indicates that spermatid number in adults depends on numbers of Sertoli cells produced during perinatal development. Endocrinology. 1988;122:787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. O'Shaughnessy PJ, Fowler PA. Endocrinology of the mammalian fetal testis. Reproduction. 2011;141:37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sweeney T, Nicol L, Roche JF, Brooks AN. Maternal exposure to octylphenol suppresses ovine fetal follicle-stimulating hormone secretion, testis size, and Sertoli cell number. Endocrinology. 2000;141:2667–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lehman MN, Coolen LM, Goodman RL. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology. 2010;151:3479–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bellingham M, Fowler PA, Amezaga MR, et al. Exposure to a complex cocktail of environmental endocrine-disrupting compounds disturbs the kisspeptin/GPR54 system in ovine hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1556–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cheng G, Coolen LM, Padmanabhan V, Goodman RL, Lehman MN. The kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cell population of the arcuate nucleus: sex differences and effects of prenatal testosterone in sheep. Endocrinology. 2010;151:301–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shibata M, Friedman RL, Ramaswamy S, Plant TM. Evidence that down regulation of hypothalamic KiSS-1 expression is involved in the negative feedback action of testosterone to regulate luteinising hormone secretion in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). J Neuroendocrinol. 2007;19:432–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Knoll JG, Clay C, Bouma G, et al. Developmental profile and sexually dimorphic expression of Kiss1 and Kiss1r in the fetal mouse brain. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;4:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Smith JT, Dungan HM, Stoll EA, et al. Differential regulation of KiSS-1 mRNA expression by sex steroids in the brain of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2976–2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Navarro VM, Castellano JM, Fernández-Fernández R, et al. Developmental and hormonally regulated messenger ribonucleic acid expression of KiSS-1 and its putative receptor, GPR54, in rat hypothalamus and potent luteinizing hormone-releasing activity of KiSS-1 peptide. Endocrinology. 2004;145:4565–4574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Navarro VM, Gottsch ML, Wu M, et al. Regulation of NKB pathways and their roles in the control of kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4265–4275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kumar D, Freese M, Drexler D, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Marquardt A, Boehm U. Murine arcuate nucleus kisspeptin neurons communicate with GnRH neurons in utero. J Neurosci. 2014;34:3756–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kumar D, Periasamy V, Freese M, Voigt A, Boehm U. In utero development of kisspeptin/GnRH neural circuitry in male mice. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3084–3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Matwijiw I, Thliveris JA, Faiman C. Hypothalamo-pituitary portal development in the ovine fetus. Biol Reprod. 1989;40:1127–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Caldani M, Antoine M, Batailler M, Duittoz A. Ontogeny of GnRH systems. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1995;49:147–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Herbison AE, d'Anglemont de Tassigny X, Doran J, Colledge WH. Distribution and postnatal development of Gpr54 gene expression in mouse brain and gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology. 2010;151:312–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hrabovszky E, Kallo I, Szlavik N, Keller E, Merchenthaler I, Liposits Z. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons express estrogen receptor-β. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2827–2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Skinner DC, Dufourny L. Oestrogen receptor β-immunoreactive neurones in the ovine hypothalamus: distribution and colocalisation with gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Caldani M, Batailler M, Thiery JC, Dubois MP. LHRH-immunoreactive structures in the sheep brain. Histochemistry. 1988;89:129–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wood RI, Newman SW, Lehman MN, Foster DL. GnRH neurons in the fetal lamb hypothalamus are similar in males and females. Neuroendocrinology. 1992;55:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Qiu J, Nestor CC, Zhang C, et al. High-frequency stimulation-induced peptide release synchronizes arcuate kisspeptin neurons and excites GnRH neurons. eLife. 2016;5:e16246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Padmanabhan V, Manikkam M, Recabarren S, Foster D. Prenatal testosterone excess programs reproductive and metabolic dysfunction in the female. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;246:165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Recabarren MP, Rojas-Garcia PP, Einspanier R, Padmanabhan V, Sir-Petermann T, Recabarren SE. Pituitary and testis responsiveness in young male sheep exposed to testosterone excess during fetal development. Reproduction. 2013;145:567–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]