ABSTRACT

Bifidobacteria constitute a specific group of commensal bacteria typically found in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of humans and other mammals. Bifidobacterium breve strains are numerically prevalent among the gut microbiota of many healthy breastfed infants. In the present study, we investigated glycosulfatase activity in a bacterial isolate from a nursling stool sample, B. breve UCC2003. Two putative sulfatases were identified on the genome of B. breve UCC2003. The sulfated monosaccharide N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate (GlcNAc-6-S) was shown to support the growth of B. breve UCC2003, while N-acetylglucosamine-3-sulfate, N-acetylgalactosamine-3-sulfate, and N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate did not support appreciable growth. By using a combination of transcriptomic and functional genomic approaches, a gene cluster designated ats2 was shown to be specifically required for GlcNAc-6-S metabolism. Transcription of the ats2 cluster is regulated by a repressor open reading frame kinase (ROK) family transcriptional repressor. This study represents the first description of glycosulfatase activity within the Bifidobacterium genus.

IMPORTANCE Bifidobacteria are saccharolytic organisms naturally found in the digestive tract of mammals and insects. Bifidobacterium breve strains utilize a variety of plant- and host-derived carbohydrates that allow them to be present as prominent members of the infant gut microbiota as well as being present in the gastrointestinal tract of adults. In this study, we introduce a previously unexplored area of carbohydrate metabolism in bifidobacteria, namely, the metabolism of sulfated carbohydrates. B. breve UCC2003 was shown to metabolize N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate (GlcNAc-6-S) through one of two sulfatase-encoding gene clusters identified on its genome. GlcNAc-6-S can be found in terminal or branched positions of mucin oligosaccharides, the glycoprotein component of the mucous layer that covers the digestive tract. The results of this study provide further evidence of the ability of this species to utilize mucin-derived sugars, a trait which may provide a competitive advantage in both the infant gut and adult gut.

INTRODUCTION

The genus Bifidobacterium represents one of the major components of the intestinal microbiota of breastfed infants (1–5) while also typically constituting between 2% and 10% of the adult intestinal microbiota (6–11). Bifidobacteria are saccharolytic microorganisms whose ability to colonize and survive in the large intestine is presumed to depend on the ability to metabolize complex carbohydrates present in this environment (12, 13). Certain bifidobacterial species, including Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum, Bifidobacterium adolescentis, and Bifidobacterium breve, utilize a range of plant/diet-derived oligosaccharides such as raffinose, arabinoxylan, galactan, and cellodextrins (14–20). Bifidobacterial metabolism of human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs) is also well described, with the typically infant-derived species B. longum subsp. infantis and Bifidobacterium bifidum being particularly well adapted to utilizing these carbon sources in the infant gut (21–23). However, the ability to utilize mucin, the glycoprotein component of the mucous layer that covers the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract, is limited to members of the B. bifidum species (21, 24). Approximately 60% of the predicted glycosyl hydrolases encoded by B. bifidum PRL2010 are predicted to be involved in mucin degradation, most of which are conserved exclusively within the B. bifidum species (21).

Host-derived glycoproteins such as mucin and proteoglycans (e.g., chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate), which are found in the colonic mucosa and/or human milk, are often highly sulfated (25–29). Human colonic mucin is heavily sulfated, which is in contrast to mucin from the stomach or small intestine, the presumed purpose of which is to protect mucin against degradation by bacterial glycosidases (30–32). Despite this apparent protective measure, glycosulfatase activity has been identified in various members of the gut microbiota, e.g., Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides ovatus, and Prevotella sp. strain RS2 (33–38).

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic sulfatases uniquely require a 3-oxoalanine (typically called Cα-formylglycine or FGly) residue at their active site (39–41). Prokaryotic sulfatases carry either a conserved cysteine (Cys) or a serine (Ser) residue, which requires posttranslational conversion to FGly in the cytosol in order to convert the enzyme to an active state (42–44). In bacteria, two distinct systems have been described for the posttranslational modification of sulfatase enzymes. In Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the conversion of the Cys58 residue to FGly is catalyzed by an FGly-generating enzyme (FGE), which requires oxygen as a cofactor (45). In Klebsiella pneumoniae, the conversion of the Ser72 residue of the atsA-encoded sulfatase is catalyzed by the AtsB enzyme, which is a member of the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet)-dependent family of radical enzymes (43, 46). Similar enzymes have also been characterized from Clostridium perfringens and Ba. thetaiotaomicron, which are active on both Cys- and Ser-type sulfatases (37, 38, 47). Crucially, these enzymes are active under anaerobic conditions and were thus designated anaerobic sulfatase-maturing enzymes (anSMEs) (38). Sulfatase activity has yet to be described for bifidobacteria. In the present study, we identify two predicted sulfatase- and anSME-encoding gene clusters in B. breve UCC2003 (and other B. breve strains) and demonstrate that one such cluster is required for the metabolism of the sulfated monosaccharide N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate (GlcNAc-6-S).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. breve UCC2003 was routinely cultured in reinforced clostridial medium (RCM; Oxoid Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom). Carbohydrate utilization by bifidobacteria was examined by using modified De Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (mMRS) medium made from first principles (48), excluding a carbohydrate source, supplemented with 0.05% (wt/vol) l-cysteine HCl (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) and a particular carbohydrate source (0.5%, wt/vol). The carbohydrates used were lactose (Sigma-Aldrich), GlcNAc-6-S (Dextra Laboratories, Reading, United Kingdom) (see below), N-acetylglucosamine-3-sulfate (GlcNAc-3-S), N-acetylgalactosamine-3-sulfate (GalNAc-3-S), and N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfate (GalNAc-6-S) (see below). In order to determine bacterial growth profiles and final optical densities, 10 ml of freshly prepared mMRS medium, supplemented with a particular carbohydrate, was inoculated with 100 μl (1%) of a stationary-phase culture of a particular strain. Uninoculated mMRS medium was used as a negative control. Cultures were incubated anaerobically for 24 h, and the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was recorded. Bifidobacterial cultures were incubated under anaerobic conditions in a modular atmosphere-controlled system (Davidson and Hardy, Belfast, Ireland) at 37°C. Escherichia coli was cultured in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) at 37°C with agitation (49). Lactococcus lactis strains were grown in M17 medium supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose at 30°C (50). Where appropriate, growth media contained tetracycline (Tet) (10 μg ml−1), chloramphenicol (Cm) (5 μg ml−1 for E. coli and L. lactis and 2.5 μg ml−1 for B. breve), erythromycin (Em) (100 μg ml−1), or kanamycin (Kan) (50 μg ml−1). Recombinant E. coli cells containing pORI19 were selected on LB agar containing Em and Kan and supplemented with X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (40 μg ml−1) and 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant feature(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Escherichia coli | ||

| EC101 | Cloning host; repA+ kmr | 92 |

| EC101-pNZ-M.Bbrll+Bbr1 | EC101 harboring a pNZ8048 derivative containing the methyltransferase-encoding genes bbrIIM and bbrIIIM from B. breve UCC2003 | 57 |

| XL1-Blue | supE44 hsdR17 recA1 gyrA96 thi relA1 lac F′ [proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15 Tn10(Tetr)] | Stratagene |

| XL1-Blue-pBC1.2-atsProm | XL1-Blue harboring pBC1.2-atsProm | This study |

| L. lactis | ||

| NZ9000 | MG1363 pepN::nisRK; nisin-inducible overexpression host | 65 |

| NZ9000-pNZ8048 | NZ9000 containing pNZ8048 | This study |

| NZ9000-pNZ-atsR2 | NZ9000 containing pNZ-atsR2 | This study |

| NZ97000 | Nisin A-producing strain | 65 |

| B. breve | ||

| UCC2003 | Isolate from a nursling stool sample | 58 |

| UCC2003-atsR2 | pORI19-tetW-atsR2 insertion mutant of B. breve UCC2003 | This study |

| UCC2003-atsT | pORI19-tetW-atsT insertion mutant of B. breve UCC2003 | This study |

| UCC2003-atsA2 | pORI19-tetW-atsA2 insertion mutant of B. breve UCC2003 | This study |

| UCC2003-atsR2-pBC1.2-atsProm | pORI19-tetW-atsR2 insertion mutant of UCC2003 containing pBC1.2-atsProm | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pAM5 | pBC1-pUC19-Tcr | 64 |

| pNZ8048 | Cmr; nisin-inducible translational fusion vector | 65 |

| pNZ-atsR2 | Cmr; pNZ8048 derivative containing a translational fusion of an atsR2-containing DNA fragment to a nisin-inducible promoter | This study |

| pORI19 | Emr repA-negative ori+; cloning vector | 92 |

| pORI19-tetW-atsR2 | Internal 408-bp fragment of atsR2 and tetW cloned into pORI19 | This study |

| pORI19-tetW-atsT | Internal 416-bp fragment of atsT and tetW cloned into pORI19 | This study |

| pORI19-tetW-atsA2 | Internal 402-bp fragment of atsA2 and tetW cloned into pORI19 | This study |

| pBC1.2 | pBC1-pSC101-Cmr | 64 |

| pBC1.2-atsProm | AtsR2 promoter region cloned into pBC1.2 | This study |

Chemical synthesis of sulfated monosaccharides.

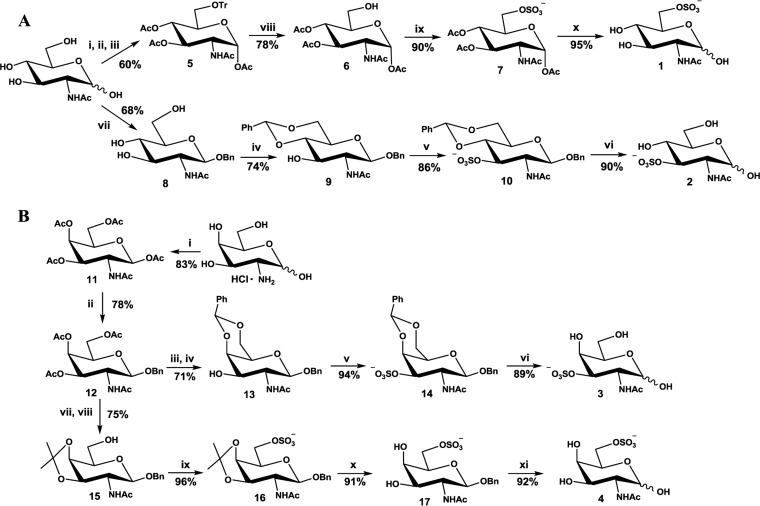

In brief, the 6-O-sulfated GlcNAc structure (structure 1) (Fig. 1A) was synthesized in four steps from GlcNAc in an overall 40% yield, while the other three target structures, 3-O-sulfated GlcNAc structure 2 (Fig. 1A), 3-O-sulfated GalNAc, and 6-O-sulfated GalNAc (structures 3 and 4, respectively) (Fig. 1B), were synthesized from their corresponding benzyl β-glycoside (structures 8 and 12) (Fig. 1A and B) in three or four steps, with an overall yield of about 60%. The benzyl glycoside was obtained either by direct alkylation of a hemiacetal (structure 8, GlcNAc) (Fig. 1A) or by glycosylation of a peracetylated precursor (structure 12, GalNAc) (Fig. 1B). Sulfations were performed by using a SO3·NEt3 complex in pyridine or dimethylformamide (DMF) (yields, 86 to 96%). Direct regioselective 6-O-tritylation of GlcNAc followed by in situ acetylation afforded compound 5, from which the trityl group was removed by using aqueous acetic acid, without any acetyl migration being detected, to yield the 6-OH derivative compound 6, the sulfation of which gave compound 7, which was subsequently deacetylated under Zemplen conditions to afford target structure 1 (Fig. 1A). Benzylidenation of compounds 8 and 12 gave 3-OH compounds 9 and 13, respectively. Sulfation (resulting in structures 10 and 14) followed by deprotection through catalytic hydrogenolysis yielded target structures 2 and 3. Isopropylidenation of compound 12 gave 6-OH compound 15, which was sulfated (resulting in structure 16) and then deprotected through acetal hydrolysis (resulting in structure 17) followed by catalytic hydrogenolysis to afford target structure 4 (Fig. 1). The experimental methods are described in further detail in the supplemental material.

FIG 1.

(A) Synthesis of 6-O- and 3-O-sulfate-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucose (structures 1 and 2). (i) BnBr, NaH, LiBr, and DMF; (ii) Ac2O and Py; (iii) NaOMe and methanol (MeOH); (iv) PhCH(OMe)2 and HCOOH; (v) SO3·NEt3 and Py at 85°C; (vi) 10% palladium on carbon (Pd/C), ethanol (EtOH), and 1,500 kPa H2; (vii) TrCl, CaSO4, and Py at 100°C (structure 1) and Ac2O (structure 2); (viii) AcOH and HBr; (ix) SO3·NEt3 and DMF at 55°C; (x) NaOMe and MeOH. (B) Synthesis of 3-O- and 6-O-sulfate-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-galactose (structures 3 and 4). (i) Ac2O and Py; (ii) BnOH, BF3·OEt2, CH2Cl2, 3 Å molecular sieve; (iii) NaOMe and MeOH; (iv) PhCH(OMe)2 and HCOOH; (v) SO3·NEt3 and DMF at 55°C; (vi) 10% Pd/C, EtOH, and 1,500 kPa H2; (vii) NaOMe and MeOH; (viii) Me2C(OMe)2, p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TSA), and DMF at 65°C; (xi) SO3·NEt3 and DMF at 55°C; (x) CF3COOH and H2O; (xi) 10% Pd/C, EtOH, and 1,000 kPa H2.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

Sequence data were obtained from the Artemis-mediated genome annotations of B. breve UCC2003 (51, 52). Database searches were performed by using the nonredundant sequence database accessible at the National Center for Biotechnology Information website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), using BLAST (53). Sequence analysis was performed by using the SeqBuilder and SeqMan programs of the DNASTAR software package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA). Inverted repeats were identified by using the PrimerSelect program of the DNASTAR software package, and a graphical representation of the identified motifs was obtained by using WebLogo software (54).

DNA manipulations.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated from B. breve UCC2003 as previously described (55). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli, L. lactis, and B. breve by using the Roche High Pure plasmid isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). An initial lysis step was performed by using 30 mg ml−1 of lysozyme for 30 min at 37°C prior to plasmid isolation from L. lactis or B. breve (56). Single-stranded oligonucleotide primers used in this study were synthesized by Eurofins (Ebersberg, Germany) (Table 2). Standard PCRs were performed by using Taq PCR master mix (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). B. breve colony PCRs were carried out as described previously (57). PCR fragments were purified by using the Roche High Pure PCR purification kit (Roche Diagnostics). Electroporation of plasmid DNA into E. coli, L. lactis, or B. breve was performed as previously described (49, 58, 59).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Purpose | Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning of a 408-bp fragment of atsR2 into pORI19 | AtsR2F | GACTAGAAGCTTGCCATCACGATCGACGACG |

| AtsR2R | TAGCATTCTAGAGCATCCCGGACGTCCACAG | |

| Cloning of a 416-bp fragment of atsT into pORI19 | AtsTF | GACTAGAAGCTTGATCTCCTTCCGCCAGCTC |

| AtsTR | TAGCATTCTAGACGTTGGTGCCGGTCAGCTG | |

| Cloning of a 402-bp fragment of atsA2 into pORI19 | AtsA2F | GACTAGAAGCTTGAATACGTCGCCTGGCTCAAG |

| AtsA2R | TAGCATTCTAGACCTCCACTGGTCGTTGTCG | |

| Amplification of tetW | TetWF | TCAGCTGTCGACATGCTCATGTACGGTAAG |

| TetWR | GCGACGGTCGACCATTACCTTCTGAAACATA | |

| Confirmation of site-specific homologous recombination | AtsR2confirm | CATCGACACGGCATACTGG |

| AtsTconfirm | CATCTTCGGCGCGTTATG | |

| AtsA2confirm | GGAAACCGACTGGACCTACAC | |

| Cloning of atsR2 into pNZ8048 | AtsR2FOR | TACGTACCATGGTGCATTTCGCATCGG |

| AtsR2REV | GCTAGCTCTAGAGTGGAATATGCGGTGCGTG | |

| Cloning of the atsR2 promoter into pBC1.2 | AtsRPromF | GTACTAAAGCTTCCAGTATGCCGTGTCGATG |

| AtsRPromR | TAGCTATCTAGACGCAATGCCAGAAACTCAGC | |

| IRD-labeled primers | AtsR2R1F | CATCGTGTTATTGGCGCGG |

| AtsR2R1R | GACGCCATATCACAGAGGGTTG | |

| AtsR2R2F | GCATGCGGCGTGAACTCC | |

| AtsR2R2R | CGCAATGCCAGAAACTCAGC | |

| AtsR2R3F | GATGTTGCCTTGCGGTATG | |

| AtsR2R3R | CAACGGCTGCCCACTGG | |

| AtsR2T1F | GGTCCTCCTTCGTCTGTGTGG | |

| AtsR2T1R | GTCGTGGCATATCGTTCGG | |

| AtsR2T2F | GGGCCGACGAAGTTGTTG | |

| AtsR2T2R | CGATGAGACCGCCGATG | |

| AtsR2T3F | CTAGCGGCATTCAGTATCGAG | |

| AtsR2T3R | GCGGCAGAACAGCAGGAAC |

Restriction sites incorporated into oligonucleotide primer sequences are indicated in italics.

Construction of B. breve UCC2003 insertion mutants.

Internal fragments of Bbr_0849, designated here atsR2 (fragment encompassing 408 bp, representing codons 134 through 271 of the 395 codons of this gene); Bbr_0851, designated atsT (fragment encompassing 416 bp, representing codons 149 through 288 of the 476 codons of this gene); and Bbr_0852, designated atsA2 (fragment encompassing 402 bp, representing codons 148 through 281 of the 509 codons of this gene) were amplified by PCR using B. breve UCC2003 chromosomal DNA as a template and primer pairs atsR2F and atsR2R, atsTF and atsTR, and atsA2F and atsA2R, respectively (Table 2). The insertion mutants were constructed as described previously (57). Site-specific recombination of potential Tet-resistant mutants was confirmed by colony PCR using primer combination TetWF and TetWR to verify tetW gene integration and primers atsR2confirm, atsTconfirm, and atsA2confirm (positioned upstream of the selected internal fragments of atsR2, atsT, and atsA2, respectively) in combination with primer TetWF to confirm integration at the correct chromosomal location.

Analysis of global gene expression using B. breve DNA microarrays.

Global gene expression was determined during log-phase growth (OD600 of ∼0.5) of B. breve UCC2003 in mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% GlcNAc-6-S, and the obtained transcriptome was compared to that obtained from B. breve UCC2003 grown in mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% ribose. Similarly, global gene expression of the insertion mutant strain B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 was determined during log-phase growth (OD600 of ∼0.5) of the mutant in mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% ribose, and the transcriptome was also compared to that obtained from B. breve UCC2003 grown in 0.5% ribose. DNA microarrays containing oligonucleotide primers representing each of the 1,864 identified open reading frames of the genome of B. breve UCC2003 were designed and obtained from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, CA, USA). RNA was isolated and purified from bifidobacterial cells by using a combination of the “Macaloid” method and the Roche High Pure RNA isolation kit, as previously described (60). The RNA level was quantified spectrophotometrically as described previously by Sambrook et al. (49). Methods for cDNA synthesis and labeling were performed as described previously (61). Hybridization, washing of the slides, and processing of the DNA microarray data were also performed as previously described (62).

Plasmid constructions.

For the construction of plasmid pNZ-atsR2, a DNA fragment encompassing the complete coding region of the predicted transcriptional regulator atsR2 (Bbr_0849) was generated by PCR amplification from chromosomal DNA of B. breve UCC2003 using PfuUltra II DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies) and primer combination atsR2FOR and atsR2REV (Table 2). The generated amplicon was digested with NcoI and XbaI and ligated into the similarly digested nisin-inducible translational fusion plasmid pNZ8048 (63). The ligation mixture was introduced into L. lactis NZ9000 by electrotransformation, and transformants were selected based on Cm resistance. The plasmid content of a number of Cmr transformants was screened by restriction analysis, and the integrity of positively identified clones was verified by sequencing.

To clone the Bbr_0849 promoter region, a DNA fragment encompassing the intergenic region between the Bbr_0849 and Bbr_0850 genes was generated by PCR amplification employing B. breve UCC2003 chromosomal DNA as a template and using PfuUltra II DNA polymerase in combination with primer pair atsRPromF and atsRPromR (Table 2). The PCR product was digested with HindIII and XbaI and ligated into similarly digested pBC1.2 (64). The ligation mixture was introduced into E. coli XL1-Blue by electrotransformation, and transformants were selected based on Tet and Cm resistance. Transformants were checked for plasmid content by restriction analysis, and the integrity of several positively identified recombinant plasmids was verified by sequencing. One of these verified recombinant plasmids, designated pBC1.2-atsProm, was introduced into B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 by electrotransformation, and transformants were selected based on Tet and Cm resistance.

Heterologous protein production.

For the heterologous expression of AtsR2, 25 ml of M17 broth supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose was inoculated with a 2% inoculum of a culture grown overnight for 16 h of L. lactis NZ9000 harboring either pNZ-atsR2 or the empty vector pNZ8048 (used as a negative control), followed by incubation at 30°C until an OD600 of ∼0.5 was reached, at which point protein expression was induced by the addition of the cell-free supernatant of a nisin-producing strain (65), followed by continued incubation for a further 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and disrupted with glass beads in a mini-bead beater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation to produce an AtsR2-containing crude cell extract.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

DNA fragments representing different portions of each of the promoter regions upstream of the atsR2 and atsT genes were prepared by PCR using 5′ IRDye 700-labeled primer pairs synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) (Table 2). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed essentially as described previously (66). In all cases, the binding reactions were performed in a final reaction mixture volume of 20 μl in the presence of poly(dI-dC) in binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM KCl, and 10% glycerol at pH 7.0). Various amounts of the crude cell extract of L. lactis NZ9000 containing pNZ-atsR2 or pNZ8048 were mixed on ice with a fixed amount of a DNA probe (0.1 pmol) and subsequently incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Samples were loaded onto a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide (PAA) gel prepared in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris-acetate [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA) and run in a 0.5× to 2.0× gradient of TAE at 100 V for 120 min in an Atto Mini PAGE system (Atto Bioscience and Biotechnology, Tokyo, Japan). Signals were detected by using an Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences, United Kingdom, Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom), and images were captured by using the supplied Odyssey software v3.0. To identify the effector molecule of AtsR2, either GlcNAc or GlcNAc-6-S was added to the binding reaction mixture in concentrations ranging from 2.5 mM to 20 mM.

Primer extension analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from exponentially growing cells of B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 or B. breve UCC2003-atsR2-pBC1.2-atsRProm in mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% ribose, as previously described (61). Primer extension was performed by annealing 1 pmol of an 5′ IRDye 700-labeled synthetic oligonucleotide to 20 μg of RNA, as previously described (67), using primer AtsR2R1F or AtsR2T1R (Table 2). Sequence ladders of the presumed atsR2 and atsT promoter regions were produced by using the same primer as the one used for the primer extension reaction and a DNA cycle sequencing kit (Jena Bioscience, Germany) and were run alongside the primer extension products to allow precise alignment of the transcriptional start site with the corresponding DNA sequence. Separation was achieved on a 6.5% Li-Cor Matrix KB Plus acrylamide gel. Signal detection and image capture were performed with a Li-Cor sequencing instrument (Li-Cor Biosciences).

Accession number(s).

The microarray data obtained in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE81240.

RESULTS

Genetic organization of the sulfatase gene clusters in B. breve UCC2003.

Based on the presence of a sulfatase-associated PFAM domain, PF00884, and the previously described N-terminally located sulfatase signature (CxPxR, where x represents a variable amino acid) (68, 69), two putative Cys-type sulfatase-encoding genes were identified on the genome of B. breve UCC2003. The first, represented by the gene with the associated locus tag Bbr_0352 (and designated here atsA1), is located in a cluster of four genes, designated the ats1 cluster, which also includes a gene encoding a predicted hypothetical membrane-spanning protein (Bbr_0349); a gene specifying a putative anSME, which contains the signature motif CxxxCxxC characteristic of the radical AdoMet-dependent superfamily (Bbr_0350, designated here atsB1) (70); and a gene specifying a predicted LacI-type transcriptional regulator (Bbr_0351, designated atsR1). Adjacent to these four genes, but oppositely oriented, three genes that encode a predicted ABC-type transport system (corresponding to locus tags Bbr_0353 through Bbr_0355) are present (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

Comparison of the sulfatase- and anSME-encoding gene clusters of B. breve UCC2003 with corresponding loci in the currently available complete B. breve genome sequences and B. longum subsp. infantis BT1. Each solid arrow represents an open reading frame. The length of the arrows (which show the locus tag) is proportional to the size of the open reading frame. The corresponding gene name, which is indicative of putative function, is given above relevant arrows at the top. Orthologues are marked with the same color. The amino acid identity of each predicted protein to its equivalent protein encoded by B. breve UCC2003, expressed as a percentage, is given above each arrow.

The second predicted sulfatase-encoding gene, Bbr_0852 (designated here atsA2), is located in a cluster of four genes (Bbr_0851 through to Bbr_0854, designated here ats2). Bbr_0851, designated atsT, encodes a predicted transporter from the major facilitator superfamily. Bbr_0853 (designated atsB2) encodes a putative anSME, which contains the signature CxxxCxxC motif. Bbr_0854 encodes a predicted membrane-spanning protein, which shares 75% amino acid identity with the deduced protein encoded by Bbr_0349 of the ats1 gene cluster (Fig. 2). The AtsA1 and AtsA2 proteins share 28% amino acid identity, while the AtsB1 and AtsB2 proteins exhibit 74% identity between each other. Interestingly, the ats2 gene cluster has a notably different GC content (63.96%) compared to the B. breve UCC2003 genome average (58.73%), whereas the GC content of the ats1 cluster (57.6%) is comparable to that of the genome.

Based on the comparative genome analysis presented in Fig. 2, we found that the putative sulfatase clusters are well conserved among the B. breve strains whose genomes were recently reported (71). Of currently available complete B. breve genomes, B. breve NCFB2258, B. breve 689B, B. breve 12L, and B. breve S27 encode clear homologues of both identified putative sulfatase gene clusters described above. In contrast, the genomes of B. breve JCM7017, B. breve JCM7019, and B. breve ACS-071-V-Sch8b contain just a single but variable putative sulfatase cluster (Fig. 2). A clear homologue of the ats1 gene cluster was also identified in the recently reported genome of B. longum subsp. infantis BT1 (GenBank accession number CP010411). No other homologues of either sulfatase-encoding gene cluster were identified within the available bifidobacterial genome sequences by BLASTP analysis.

Growth of B. breve UCC2003 on sulfated monosaccharides.

The presence of two putative sulfatase-encoding clusters in the genome of B. breve UCC2003 suggests that this gut commensal is capable of removing a sulfate ester from a sulfated compound, possibly a sulfated carbohydrate. In mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% GlcNAc-6-S as the sole carbon source, the strain was capable of substantial growth (final OD600 values following growth overnight varied between 0.6 and 0.8). However, no appreciable growth was observed on GlcNAc-3-S, GalNAc-3-S, or GalNAc-6-S. For growth on the positive control, 0.5% lactose, the strain reached an OD600 of almost 2, which is comparable to data from previous studies with this strain (17, 72, 73) (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

(A) Final OD600 values obtained following 24 h of growth of B. breve UCC2003 on mMRS medium without supplementation with a carbon source (negative control) or containing 0.5% (wt/vol) lactose, GlcNAc-6-S, GlcNAc-3-S, GalNAc-6-S, or GalNAc-3-S as the sole carbon source. (B) Final OD600 values obtained following 24 h of growth of B. breve UCC2003, B. breve UCC2003-atsT, and B. breve UCC2003-atsA2 in mMRS medium without supplementation with a carbon source (negative control) (horizontally striped bars) or containing 0.5% (wt/vol) lactose (diagonally striped bars) or GlcNAc-6-S (solid gray-filled bars) as the sole carbon source. The results are the mean values obtained from two separate experiments. Error bars represent the standard deviations.

Genome response of B. breve UCC2003 to growth on GlcNAc-6-S.

In order to investigate which genes are responsible for GlcNAc-6-S metabolism in B. breve UCC2003, global gene expression was determined by microarray analysis during growth of the strain in mMRS medium supplemented with GlcNAc-6-S and compared with the gene expression of the strain grown in mMRS medium supplemented with ribose. Ribose was considered an appropriate carbohydrate for comparative transcriptome analysis because the genes involved in ribose metabolism are known, and furthermore, it has successfully been used in a number of transcriptome studies of this strain (17, 18, 72–74). Of the two predicted sulfatase- and anSME-encoding gene clusters of B. breve UCC2003 (see above), transcription of the ats2 gene cluster was significantly upregulated (fold change of >3.0; P value of <0.001) during growth on GlcNAc-6-S, while no (significant) difference in the level of transcription was observed for the ats1 gene cluster (Table 3). Interestingly, three other gene clusters were also significantly upregulated (corresponding to locus tags Bbr_0846 through Bbr_0849 [Bbr_0846–0849 gene cluster], Bbr_1585 through Bbr_1590, and Bbr_1247 through Bbr_1249) (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of GlcNAc-6-S on the transcriptome of B. breve UCC2003a

| Locus tag (gene) | Predicted function | Level of upregulation (fold) |

|---|---|---|

| Bbr_0846 (nagA1) | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 12.63 |

| Bbr_0847 (nagB2) | Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | 6.17 |

| Bbr_0848 (nagK) | Sugar kinase, ROK family | 9.85 |

| Bbr_0849 (atsR2) | Transcriptional regulator, ROK family | 8.58 |

| Bbr_0851 (atsT) | Carbohydrate transport protein | 96.75 |

| Bbr_0852 (atsA2) | Sulfatase | 35.36 |

| Bbr_0853 (atsB2) | anSME | 31.25 |

| Bbr_0854 | Hypothetical membrane-spanning protein | 4.175 |

| Bbr_1247 (nagA2) | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | 10.84 |

| Bbr_1248 (nagB3) | Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | 11.88 |

| Bbr_1249 | Transcriptional regulator, ROK family | 3.07 |

| Bbr_1585 (galE) | UDP-glucose 4-epimerase | 3.09 |

| Bbr_1586 (nahK) | N-Acetylhexosamine kinase | 4.96 |

| Bbr_1587 (lnbP) | Lacto-N-biose phosphorylase | 6.58 |

| Bbr_1588 | Permease protein of the ABC transporter system | 6.24 |

| Bbr_1589 | Permease protein of the ABC transporter system | 8.27 |

| Bbr_1590 | Solute-binding protein of the ABC transporter system | 23.97 |

The cutoff point is 3-fold, with a P value of <0.001.

FIG 4.

Schematic representation of the four B. breve UCC2003 gene clusters upregulated during growth on GlcNAc-6-S as the sole carbon source. The length of the arrows (which show the locus tag) is proportional to the size of the open reading frame, and the gene locus name, which is indicative of its putative function, is given at the top. Genes are grouped by color based on their predicted function in carbohydrate metabolism.

Within the Bbr_0846–0849 gene cluster, which is separated from the ats2 cluster by a single gene (Fig. 3), Bbr_0846 (nagA1) and Bbr_0847 (nagB2) are predicted to encode an N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate (GlcNAc-6-P) deacetylase and a glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase, respectively. Bbr_0848 (designated here nagK) encodes a predicted repressor open reading frame kinase (ROK) family kinase, which contains the characteristic DxGxT motif at its N-terminal end (75). The B. breve UCC2003-encoded NagK protein exhibits 42% similarity at the protein level to the previously characterized E. coli K-12-encoded, ROK family NagK protein, which phosphorylates GlcNAc to produce GlcNAc-6-P (76). Therefore, this cluster is predicted to encode enzymes for the complete GlcNAc catabolic pathway, as previously described for E. coli, whereby GlcNAc is first phosphorylated by NagK, producing GlcNAc-6-P, followed by NagA-mediated deacetylation to produce glucosamine-6-phosphate and NagB-mediated deamination and isomerization to produce fructose-6-phosphate (76, 77). Bbr_0849 encodes a predicted transcriptional regulator from the ROK family (designated here atsR2).

The Bbr_1585–1590 cluster includes a predicted UDP-glucose-4-epimerase (Bbr_1585 [galE]), a predicted N-acetylhexosamine-1-kinase (Bbr_1586 [nahK]), and a predicted lacto-N-biose (LNB) (Galβ1-3GlcNAc) phosphorylase (Bbr_1586 [lnbP]), representing three of the four enzymes required for the degradation of galacto-N-biose (GNB) (Galβ1-3GalNAc), which is found in mucin, or LNB, a known HMO (78, 79). The other three genes of this cluster, Bbr_1588–1590, encode a predicted ABC transport system, including two predicted permease proteins and a solute-binding protein, respectively (Fig. 4). This gene cluster was previously shown to be transcriptionally upregulated when B. breve UCC2003 was grown in coculture with B. bifidum PRL2010 in mucin (80).

Finally, the Bbr_1247–1249 cluster contains an N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase (Bbr_1247)-encoding gene and a glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase (Bbr_1248)-encoding gene, designated nagA2 and nagB3, respectively. These genes were previously shown to be upregulated during B. breve UCC2003 growth on sialic acid (72). The NagA1 protein shares 74% identity with NagA2, while the NagB2 protein shares 84% identity with NagB1 of the nan-nag cluster for sialic acid metabolism (72) and 84% identity with NagB3. Bbr_1249 encodes a predicted transcriptional ROK family regulator (Fig. 4).

Disruption of the atsT and atsA2 genes.

In order to investigate if the disruption of individual genes from the ats2 gene cluster would affect the ability of B. breve UCC2003 to utilize GlcNAc-6-S, insertion mutations were constructed in the atsT and atsA2 genes, resulting in B. breve strain UCC2003-atsT and B. breve strain UCC2003-atsA2, respectively (see Materials and Methods). The insertion mutants were analyzed for their ability to grow in mMRS medium supplemented with GlcNAc-6-S compared to B. breve UCC2003. As expected, and in contrast to the wild type, there was a complete lack of growth of B. breve UCC2003-atsT and B. breve UCC2003-atsA2 in medium containing GlcNAc-6-S as the sole carbon source (Fig. 3B), thus demonstrating the involvement of the disrupted genes in GlcNAc-6-S metabolism. Growth of the insertion mutants was not impaired on lactose, where all strains reached final OD600 values comparable to that reached by the wild-type strain (Fig. 3B).

Transcriptome of B. breve UCC2003-atsR2.

The Bbr_0846–0849 gene cluster, which is upregulated when B. breve UCC2003 is grown on GlcNAc-6-S, and the ats2 gene cluster are separated by just a single gene (Fig. 2). An insertion mutant was constructed in the predicted ROK-type transcriptional regulator-encoding gene Bbr_0849 (atsR2). It was hypothesized that if this gene encoded a repressor, mutation of the gene would lead to increased transcription levels of the genes that it controls, even in the absence of the inducing carbohydrate. Microarray data revealed that in comparison to B. breve UCC2003, the genes of the ats2 cluster were indeed significantly upregulated (>3.0-fold change; P < 0.001) in the mutant strain, thus identifying atsR2 as a transcriptional repressor (Table 4). Transcription of the Bbr_0846–0849 gene cluster was downregulated in the mutant strain compared to the wild type when both strains were grown on ribose. It is speculated that since atsR2 represents the first gene of this presumed operon (Fig. 2), the insertion mutation caused a (negative) polar effect on the transcription of the genes located downstream.

TABLE 4.

Transcriptome analysis of B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 compared to B. breve UCC2003 grown on 0.5% (wt/vol) ribosea

| Locus tag (gene) | Predicted function | Fold upregulation | Fold downregulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bbr_0846 (nagA1) | N-Acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase | − | 3.77 |

| Bbr_0847 (nagB2) | Glucosamine-6-phosphate isomerase | − | 3.35 |

| Bbr_0848 (nagK) | Sugar kinase, ROK family | − | 4.45 |

| Bbr_0850 | Aldose-1-epimerase | 4.58 | − |

| Bbr_0851 (atsT) | Carbohydrate transport protein | 106.28 | − |

| Bbr_0852 (atsA2) | Sulfatase | 59.58 | − |

| Bbr_0853 (atsB2) | anSME | 15.57 | − |

| Bbr_0854 | Hypothetical membrane-spanning protein | 9.09 | − |

The cutoff point is 3-fold, with a P value of <0.001; values below the cutoff are indicated by a minus.

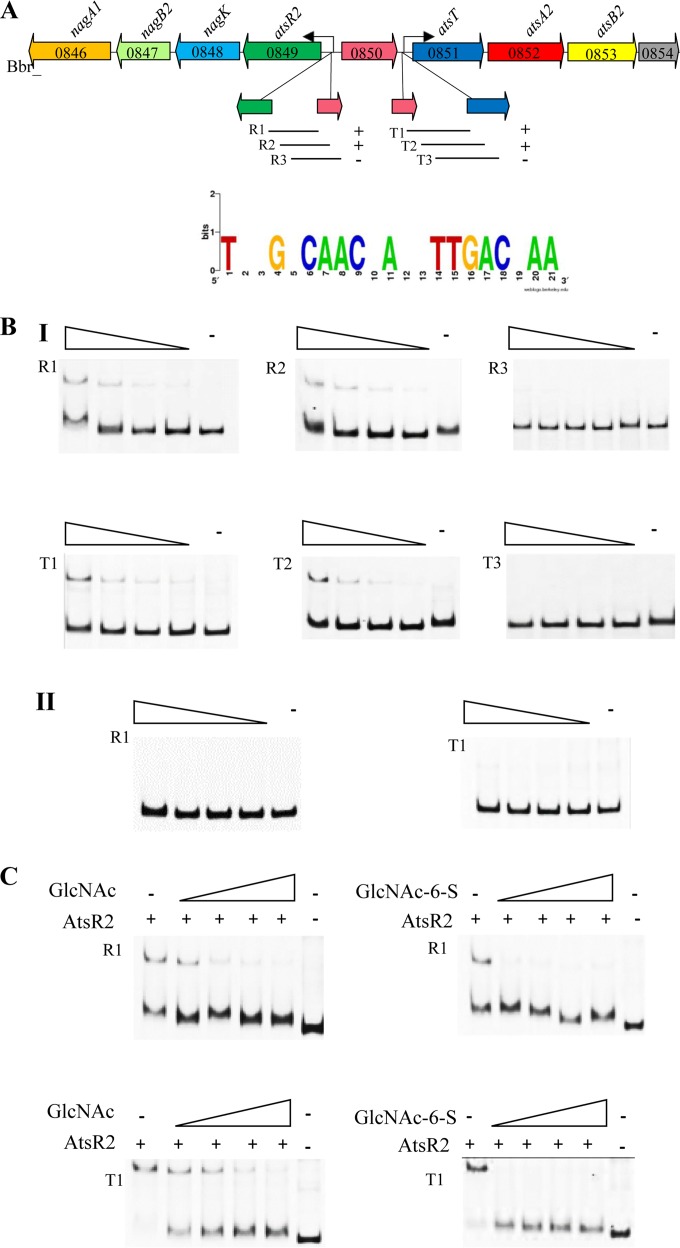

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays.

In order to determine if the AtsR2 protein directly interacts with promoter regions of the ats2 gene cluster, crude cell extracts of L. lactis NZ9000-pNZ-atsR2 were used to perform EMSAs, with crude cell extracts of L. lactis NZ9000-pNZ8048 (empty vector) being used as a negative control. As expected, the negative control did not alter the electrophoretic behavior of any of the tested DNA fragments (Fig. 5B). The results obtained with crude cell extracts expressing AtsR2 demonstrate that this presumed regulator specifically binds to DNA fragments encompassing the upstream regions of atsR2 and atsT (Fig. 5A and B). Dissection of the promoter region of atsR2 showed that AtsR2 binding required a 184-bp region, within which a 21-bp imperfect inverted repeat was identified. Similarly, dissection of the atsT promoter region revealed that AtsR2 binding required a 192-bp region, which also includes a 21-bp imperfect repeat, similar to that identified upstream of atsR2. When either of the inverted repeats was excluded, binding of AtsR2 to such DNA fragments was abolished, suggesting that these inverted repeats contained the operator sequence of AtsR2 (Fig. 5A and B).

FIG 5.

(A) Schematic representation of the ats2 gene cluster of B. breve UCC2003 and DNA fragments used in EMSAs for the atsR2 and atsT promoter regions, together with a WebLogo representation of the predicted operator of AtsR2. Plus or minus signs indicate the ability or inability of AtsR2 to bind to the DNA fragment. The bent arrows represent the position and direction of the proven promoter sequences (Fig. 6). (B) EMSAs showing the interactions of a crude cell extract containing pNZ-AtsR2 with DNA fragments R1, R2, R3, T1, T2, and T3 (I) and of a crude cell extract containing pNZ8048 (empty vector) with DNA fragments R1 and T1 (II). The minus symbol indicates reaction mixtures to which no crude cell extract was added, while the remaining lanes represent binding reactions with the respective DNA probes incubated with increasing amounts of the crude cell extract. Each successive lane from right to left represents a doubling of the amount of the crude cell extract. (C) EMSAs showing AtsR2 interactions with DNA fragments R1 and T1 with the addition of GlcNAc or GlcNAc-6-S at concentrations ranging from 2.5 mM to 20 mM.

To demonstrate if the binding of AtsR2 to its DNA target is affected by the presence of a carbohydrate effector molecule, GlcNAc and GlcNAc-6-S were tested for their effects on the formation of the AtsR2-DNA complex. The ability of AtsR2 to bind to the promoter region of atsR2 or atsT was eliminated in the presence of 2.5 mM GlcNAc-6-S, the lowest concentration used in this assay. The presence of GlcNAc was shown to inhibit the binding of AtsR2 to the atsR2 and atsT promoter regions but only at GlcNAc concentrations above 5 mM (Fig. 5C). This finding suggests that while GlcNAc-6-S has the highest affinity for the regulator and is therefore the most likely effector of this repressor protein, the structurally similar GlcNAc is also able to bind this regulator but at concentrations that are probably not physiologically relevant.

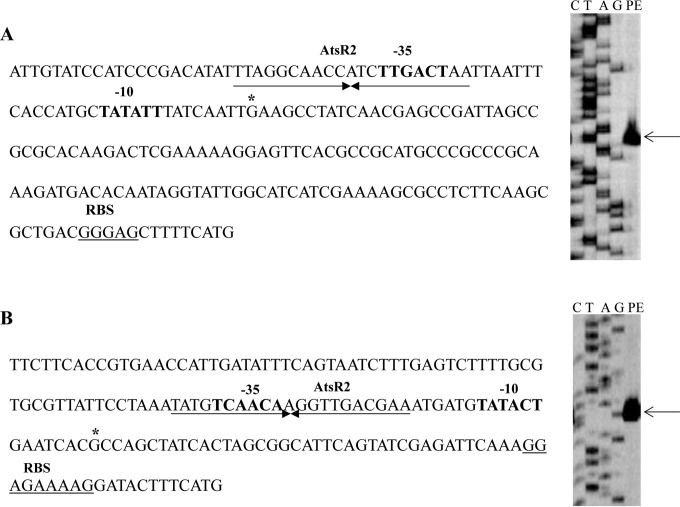

Identification of the transcription start sites of atsR2 and atsT.

Based on the EMSA results and the transcriptome of B. breve UCC2003-atsR2, it was deduced that an AtsR2-dependent promoter is located upstream of both atsR2 and atsT (Fig. 2). In order to determine the transcriptional start site of these presumed promoters, primer extension analysis was performed by using RNA extracted from B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 grown in mMRS medium supplemented with 0.5% ribose. Microarray analysis had shown that the expression levels of atsT were high when the B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 strain was grown on ribose (Table 4). For this reason, the mutant strain was considered the most suitable for primer extension analysis. For the atsR2 promoter region, initial attempts to attain a primer extension product from mRNA isolated from B. breve UCC2003-atsR2 cells were unsuccessful. In an attempt to increase the amount of mRNA transcripts of this promoter region, a DNA fragment encompassing the deduced promoter region was cloned into pBC1.2 and introduced into B. breve UCC2003-atsR2, generating B. breve strain UCC2003-atsR2-pBC1.2-atsRProm. A primer extension product was obtained for the atsT promoter region using mRNA isolated from B. breve UCC2003-atsR2; therefore, it was not necessary to clone this promoter. Single extension products were identified upstream of atsR2 and atsT (Fig. 6). Potential promoter recognition sequences resembling consensus −10 and −35 hexamers were identified upstream of each of the transcription start sites (Fig. 6). The deduced operator sequences of AtsR2 overlap the respective −35 or −10 sequences, consistent with our findings that AtsR2 acts as a transcriptional repressor.

FIG 6.

Schematic representation of the atsR2 (A) and atsT (B) promoter regions. Boldface type and underlining indicate −10 and −35 hexamers (as deduced from the primer extension results) and the ribosomal binding site (RBS); the transcriptional start site is indicated by an asterisk. The arrows below the indicated DNA sequences indicate the inverted repeats that represent the presumed AtsR2-binding site. The arrows in the right panels indicate the primer extension products. C, cytosine; T, thymine; A, adenine; G, guanine; PE, primer extension product.

DISCUSSION

A large-scale metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from 13 individuals of various ages revealed that genes predicted to encode anSMEs are enriched in the gut microbiomes of humans compared to microbial communities not in the gut (81). Interestingly, in that same study, it was found that such genes are found more commonly in members of the gut microbiota of adults and weaned children than in unweaned infants. The present study describes two gene clusters in a bacterium isolated from an infant, namely, B. breve UCC2003, each encoding a (predicted) sulfatase and the accompanying anSME as well as an associated transport system and transcriptional regulator. The ats2 gene cluster was shown to be required for the metabolism of GlcNAc-6-S, while GlcNAc-3-S, GalNAc-3-S, and GalNAc-6-S did not support the growth of B. breve UCC2003. The substrate(s) for the sulfatase encoded by the ats1 gene cluster is as yet unknown. However, as recently shown in a study of sulfatases from Ba. thetaiotaomicron, these enzymes can vary quite significantly in their substrate specificities. It is therefore possible that, similar to the recently characterized BT_3349 and BT_1596 enzymes from Ba. thetaiotaomicron, the AtsA1 sulfatase might be active on sulfated di- or oligosaccharides rather than monosaccharides (35) or that the transport system encoded by the ats1 cluster is specific for an as-yet-unknown sulfated substrate. However, at present, this is mere speculation, and further study is required to expand this premise.

Interestingly, the two gene clusters ats1 and ats2 are quite dissimilar in terms of their genetic organizations. The gene order and composition of the ats1 cluster resemble those of a typical bifidobacterial carbohydrate utilization cluster, as it includes genes encoding a predicted ABC-type transport system, a LacI-type repressor (atsR1), and the carbohydrate-active atsA1-encoded sulfatase and atsB-encoded anSME, which in this case replace the typical glycosyl hydrolase-encoding gene(s) (16, 82). In the ats2 cluster, the atsT gene encodes a predicted transporter of the major facilitator superfamily, while the atsA2 and atsB2 genes are adjacent, as is also the case for their homologous genes in K. pneumoniae and Prevotella strain RS2 (83, 84). We obtained compelling evidence that the ats2 cluster is coregulated with the Bbr_0846–0849 cluster by the ROK family transcriptional repressor AtsR2. The only previously characterized bifidobacterial ROK family transcriptional regulator is RafA, the transcriptional activator of the raffinose utilization cluster in B. breve UCC2003 (73). The Bbr_0846–0848 genes are presumed to be involved in the metabolism of GlcNAc following the removal of the sulfate residue from GlcNAc-6-S. The fructose-6-phosphate produced from GlcNAc by the combined activities of NagK, NagA, and NagB is expected to enter the fructose-6-phosphate phosphoketolase pathway or bifid shunt, the central metabolic pathway of bifidobacteria (85). It is interesting that B. breve UCC2003 is capable of growth on GlcNAc-6-S, but apparently not on GlcNAc, as a sole carbon source (16). Since the B. breve UCC2003 genome seems to encode the enzymes required to metabolize GlcNAc, this suggests that the atsT transporter has (high) affinity for only the sulfated form of this N-acetylated carbohydrate.

A novel method of desulfating mucin that does not require a sulfatase enzyme has been characterized for Prevotella strain RS2, whereby a sulfoglycosidase removes GlcNAc-6-S from purified porcine gastric mucin (86). The presence of a signal sequence on this glycosulfatase (86), thus indicating extracellular activity, is interesting in relation to the present study, as it presents a source of GlcNAc-6-S to B. breve strains, which is suggestive of a cross-feeding opportunity for members of this species. This is particularly noteworthy considering that the sulfatase enzymes produced by B. breve UCC2003 are intracellular, implying that B. breve UCC2003 is reliant on the extracellular glycosyl hydrolase activity of other members of the gut microbiota in order to gain access to mucin-derived sulfated monosaccharides. Recent studies have shown that B. breve UCC2003 employs a cross-feeding strategy to great effect, as it can utilize components of 3′ sialyllactose (a HMO) and mucin following the degradation of these sugars by B. bifidum PRL2010, whereas in the absence of B. bifidum PRL2010, it is not capable of utilizing either of these sugars as a sole carbon source (72, 80). A recent study provided further transcriptomic evidence for carbohydrate cross-feeding between bifidobacterial species. Four bifidobacterial strains, namely, B. bifidum PRL2010, B. breve 12L, B. adolescentis 22L, and B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 25697, were cultivated either in pairs (biassociation) or as a combination of all four strains (multiassociation) under in vivo conditions in a murine model. In all strains, transcription of predicted glycosyl hydrolase-encoding genes, particularly those involved in xylose or starch utilization, was affected by co- or multiassociation. In relation to xylose metabolism, the authors of that study speculated that in co- or multiassociation, the combined glycosyl hydrolase activities of the strains may allow them to degrade xylose-containing polysaccharides that would otherwise be inaccessible (87).

For Ba. thetaiotaomicron, the in vivo contribution of sulfatase activity to bacterial fitness has been well established. In previous studies of chondroitin sulfate and heparan sulfate metabolism by this species, mutagenesis of a gene designated chuR, which was first predicted to encode a regulatory protein but was later found to encode an anSME, resulted in an inability to compete with wild-type Ba. thetaiotaomicron in germfree mice (37, 88). In a recent study, 28 predicted sulfatase-encoding genes were identified in the genome of Ba. thetaiotaomicron, 20 of which are predicted extracellular enzymes, yet the previously described chuR gene is the sole anSME-encoding gene (36, 89, 90). Recently, this anSME was shown to be of significant importance in this strain's ability to colonize the gut, as an isogenic derivative of this strain (designated ΔanSME) carrying a deletion in the anSME-encoding gene displayed reduced fitness in vivo (36). The authors of that study speculated that anSME activity and associated sulfatase activities are important as the bacterium adapts to the gut environment (36). Given that sulfatase activity within the Bifidobacterium genus is limited to the B. breve species and a single strain of B. longum subsp. infantis (at least based on currently available genome sequences), it is interesting to speculate on the effect that this activity may have on bacterial fitness in the large intestine. It is intriguing that human intestinal mucins increase in acidity along the intestinal tract, with more than half of mucin oligosaccharide structures in the distal colon containing either sialic and/or sulfate residues (91). We recently showed that 11 of 14 strains of B. breve tested were capable of growth on sialic acid, while sialic acid utilization genes can also be found in the genomes of B. longum subsp. infantis strains (20, 22, 72). The ability of B. breve strains and possibly certain B. longum subsp. infantis strains to utilize both sialic acid and sulfated GlcNAc-6-S may provide them with a competitive advantage over other members of the Bifidobacterium genus and other members of the gut microbiota, thus contributing to their successful colonization ability in this highly competitive environment.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02022-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Turroni F, Peano C, Pass DA, Foroni E, Severgnini M, Claesson MJ, Kerr C, Hourihane J, Murray D, Fuligni F, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, De Bellis G, O'Toole PW, van Sinderen D, Marchesi JR, Ventura M. 2012. Diversity of bifidobacteria within the infant gut microbiota. PLoS One 7:. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vaishampayan PA, Kuehl JV, Froula JL, Morgan JL, Ochman H, Francino MP. 2010. Comparative metagenomics and population dynamics of the gut microbiota in mother and infant. Genome Biol Evol 2:53–66. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bäckhed F, Roswall J, Peng Y, Feng Q, Jia H, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Li Y, Xia Y, Xie H, Zhong H, Khan MT, Zhang J, Li J, Xiao L, Al-Aama J, Zhang D, Lee YS, Kotowska D, Colding C, Tremaroli V, Yin Y, Bergman S, Xu X, Madsen L, Kristiansen K, Dahlgren J, Wang J. 2015. Dynamics and stabilization of the human gut microbiome during the first year of life. Cell Host Microbe 17:690–703. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jost T, Lacroix C, Braegger CP, Rochat F, Chassard C. 2014. Vertical mother-neonate transfer of maternal gut bacteria via breastfeeding. Environ Microbiol 16:2891–2904. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tannock GW, Lawley B, Munro K, Gowri Pathmanathan S, Zhou SJ, Makrides M, Gibson RA, Sullivan T, Prosser CG, Lowry D, Hodgkinson AJ. 2013. Comparison of the compositions of the stool microbiotas of infants fed goat milk formula, cow milk-based formula, or breast milk. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:3040–3048. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03910-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turroni F, Ribbera A, Foroni E, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2008. Human gut microbiota and bifidobacteria: from composition to functionality. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 94:35–50. doi: 10.1007/s10482-008-9232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson AF, Lindberg M, Jakobsson H, Bäckhed F, Nyrén P, Engstrand L. 2008. Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS One 3:. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwielehner J, Liszt K, Handschur M, Lassl C, Lapin A, Haslberger AG. 2009. Combined PCR-DGGE fingerprinting and quantitative-PCR indicates shifts in fecal population sizes and diversity of Bacteroides, bifidobacteria and Clostridium cluster IV in institutionalized elderly. Exp Gerontol 44:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agans R, Rigsbee L, Kenche H, Michail S, Khamis HJ, Paliy O. 2011. Distal gut microbiota of adolescent children is different from that of adults. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 77:404–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishijima S, Suda W, Oshima K, Kim S-W, Hirose Y, Morita H, Hattori M. 6 March 2016. The gut microbiome of healthy Japanese and its microbial and functional uniqueness. DNA Res doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Milani C, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Duranti S, Turroni F, Ferrario C, Mangifesta M, Viappiani A, Ferretti P, Gorfer V, Tett A, Segata N, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2015. Exploring vertical transmission of bifidobacteria from mother to child. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:7078–7087. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milani C, Lugli GA, Duranti S, Turroni F, Mancabelli L, Ferrario C, Mangifesta M, Hevia A, Viappiani A, Scholz M, Arioli S, Sanchez B, Lane J, Ward DV, Hickey R, Mora D, Segata N, Margolles A, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2015. Bifidobacteria exhibit social behavior through carbohydrate resource sharing in the gut. Sci Rep 5:15782. doi: 10.1038/srep15782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milani C, Turroni F, Duranti S, Lugli GA, Mancabelli L, Ferrario C, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 20 November 2015. Genomics of the genus Bifidobacterium reveals species-specific adaptation to the glycan-rich gut environment. Appl Environ Microbiol doi: 10.1128/AEM.03500-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margolles A, de los Reyes-Gavilan CG. 2003. Purification and functional characterization of a novel alpha-l-arabinofuranosidase from Bifidobacterium longum B667. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:5096–5103. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5096-5103.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pokusaeva K, O'Connell-Motherway M, Zomer A, MacSharry J, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2011. Cellodextrin utilization by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:1681–1690. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01786-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pokusaeva K, Fitzgerald G, van Sinderen D. 2011. Carbohydrate metabolism in bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr 6:285–306. doi: 10.1007/s12263-010-0206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Connell Motherway M, Kinsella M, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2013. Transcriptional and functional characterization of genetic elements involved in galacto-oligosaccharide utilization by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb Biotechnol 6:67–79. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Connell KJ, O'Connell Motherway M, O'Callaghan J, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP, Ventura M, Stanton C, van Sinderen D. 2013. Metabolism of four α-glycosidic linkage-containing oligosaccharides by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:6280–6292. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01775-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivière A, Moens F, Selak M, Maes D, Weckx S, De Vuyst L. 2014. The ability of bifidobacteria to degrade arabinoxylan oligosaccharide constituents and derived oligosaccharides is strain dependent. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:204–217. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02853-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Callaghan A, Bottacini F, O'Connell Motherway M, van Sinderen D. 2015. Pangenome analysis of Bifidobacterium longum and site-directed mutagenesis through by-pass of restriction-modification systems. BMC Genomics 16:1–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turroni F, Bottacini F, Foroni E, Mulder I, Kim J-H, Zomer A, Sanchez B, Bidossi A, Ferrarini A, Giubellini V, Delledonne M, Henrissat B, Coutinho P, Oggioni M, Fitzgerald G, Mills D, Margolles A, Kelly D, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 2010. Genome analysis of Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 reveals metabolic pathways for host-derived glycan foraging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:19514–19519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011100107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sela DA, Chapman J, Adeuya A, Kim JH, Chen F, Whitehead TR, Lapidus A, Rokhsar DS, Lebrilla CB, German JB, Price NP, Richardson PM, Mills DA. 2008. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis reveals adaptations for milk utilization within the infant microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:18964–18969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809584105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrido D, Ruiz-Moyano S, Lemay DG, Sela DA, German JB, Mills DA. 2015. Comparative transcriptomics reveals key differences in the response to milk oligosaccharides of infant gut-associated bifidobacteria. Sci Rep 5:13517. doi: 10.1038/srep13517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruas-Madiedo P, Gueimonde M, Fernández-García M, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Margolles A. 2008. Mucin degradation by Bifidobacterium strains isolated from the human intestinal microbiota. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1936–1940. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02509-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newburg D, Linhardt R, Ampofo S, Yolken R. 1995. Human milk glycosaminoglycans inhibit HIV glycoprotein gp120 binding to its host cell CD4. J Nutr 125:419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oshiro M, Ono K, Suzuki Y, Ota H, Katsuyama T, Mori N. 2001. Immunohistochemical localization of heparan sulfate proteoglycan in human gastrointestinal tract. Histochem Cell Biol 115:373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eliakim R, Gilead L, Ligumsky M, Okon E, Rachmilewitz D, Razin E. 1986. Histamine and chondroitin sulfate E proteoglycan released by cultured human colonic mucosa: indication for possible presence of E mast cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83:461–464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsson JM, Karlsson H, Sjovall H, Hansson GC. 2009. A complex, but uniform O-glycosylation of the human MUC2 mucin from colonic biopsies analyzed by nanoLC/MSn. Glycobiology 19:756–766. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guérardel Y, Morelle W, Plancke Y, Lemoine J, Strecker G. 1999. Structural analysis of three sulfated oligosaccharides isolated from human milk. Carbohydr Res 320:230–238. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6215(99)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filipe M. 1978. Mucins in the human gastrointestinal epithelium: a review. Invest Cell Pathol 2:195–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brockhausen I. 2003. Sulphotransferases acting on mucin-type oligosaccharides. Biochem Soc Trans 31:318–325. doi: 10.1042/bst0310318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson AM, Wright DP. 1997. Bacterial glycosulphatases and sulphomucin degradation. Can J Gastroenterol 11:361–366. doi: 10.1155/1997/642360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salyers AA, Vercellotti JR, West SE, Wilkins TD. 1977. Fermentation of mucin and plant polysaccharides by strains of Bacteroides from the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol 33:319–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberton A, McKenzie C, Sharfe N, Stubbs L. 1993. A glycosulphatase that removes sulphate from mucus glycoprotein. Biochem J 293:683–689. doi: 10.1042/bj2930683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ulmer JE, Vilén EM, Namburi RB, Benjdia A, Beneteau J, Malleron A, Bonnaffé D, Driguez P-A, Descroix K, Lassalle G, Le Narvor C, Sandström C, Spillmann D, Berteau O. 2014. Characterization of glycosaminoglycan (GAG) sulfatases from the human gut symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron reveals the first GAG-specific bacterial endosulfatase. J Biol Chem 289:24289–24303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.573303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benjdia A, Martens EC, Gordon JI, Berteau O. 2011. Sulfatases and a radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) enzyme are key for mucosal foraging and fitness of the prominent human gut symbiont, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J Biol Chem 286:25973–25982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benjdia A, Subramanian S, Leprince J, Vaudry H, Johnson MK, Berteau O. 2008. Anaerobic sulfatase-maturating enzymes, first dual substrate radical S-adenosylmethionine enzymes. J Biol Chem 283:17815–17826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710074200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berteau O, Guillot A, Benjdia A, Rabot S. 2006. A new type of bacterial sulfatase reveals a novel maturation pathway in prokaryotes. J Biol Chem 281:22464–22470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602504200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bond CS, Clements PR, Ashby SJ, Collyer CA, Harrop SJ, Hopwood JJ, Guss JM. 1997. Structure of a human lysosomal sulfatase. Structure 5:277–289. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(97)00185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lukatela G, Krauss N, Theis K, Selmer T, Gieselmann V, Von Figura K, Saenger W. 1998. Crystal structure of human arylsulfatase A: the aldehyde function and the metal ion at the active site suggest a novel mechanism for sulfate ester hydrolysis. Biochemistry 37:3654–3664. doi: 10.1021/bi9714924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt B, Selmer T, Ingendoh A, von Figura K. 1995. A novel amino acid modification in sulfatases that is defective in multiple sulfatase deficiency. Cell 82:271–278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90314-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beil S, Kehrli H, James P, Staudenmann W, Cook AM, Leisinger T, Kertesz MA. 1995. Purification and characterization of the arylsulfatase synthesized by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO during growth in sulfate-free medium and cloning of the arylsulfatase gene (atsA). Eur J Biochem 229:385–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.0385k.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szameit C, Miech C, Balleininger M, Schmidt B, von Figura K, Dierks T. 1999. The iron sulfur protein AtsB is required for posttranslational formation of formylglycine in the Klebsiella sulfatase. J Biol Chem 274:15375–15381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miech C, Dierks T, Selmer T, von Figura K, Schmidt B. 1998. Arylsulfatase from Klebsiella pneumoniae carries a formylglycine generated from a serine. J Biol Chem 273:4835–4837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlson BL, Ballister ER, Skordalakes E, King DS, Breidenbach MA, Gilmore SA, Berger JM, Bertozzi CR. 2008. Function and structure of a prokaryotic formylglycine-generating enzyme. J Biol Chem 283:20117–20125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800217200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang Q, Peng J, Dierks T. 2004. Post-translational formylglycine modification of bacterial sulfatases by the radical S-adenosylmethionine protein AtsB. J Biol Chem 279:14570–14578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grove TL, Ahlum JH, Qin RM, Lanz ND, Radle MI, Krebs C, Booker SJ. 2013. Further characterization of Cys-type and Ser-type anaerobic sulfatase maturating enzymes suggests a commonality in mechanism of catalysis. Biochemistry 52:2874–2887. doi: 10.1021/bi400136u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Man JC, Rogosa M, Sharpe ME. 1960. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J Appl Bacteriol 23:130–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1960.tb00188.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terzaghi BE, Sandine WE. 1975. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol 29:807–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rutherford K, Parkhill J, Crook J, Horsnell T, Rice P, Rajandream M-A, Barrell B. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualization and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944–945. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.10.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Connell Motherway M, Zomer A, Leahy SC, Reunanen J, Bottacini F, Claesson MJ, O'Brien F, Flynn K, Casey PG, Moreno Munoz JA, Kearney B, Houston AM, O'Mahony C, Higgins DG, Shanahan F, Palva A, de Vos WM, Fitzgerald GF, Ventura M, O'Toole PW, van Sinderen D. 2011. Functional genome analysis of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 reveals type IVb tight adherence (Tad) pili as an essential and conserved host-colonization factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:11217–11222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105380108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia J-M, Brenner SE. 2004. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riordan O. 1998. Studies on antimicrobial activity and genetic diversity of Bifidobacterium species: molecular characterization of a 5.75 kb plasmid and a chromosomally encoded recA gene homologue from Bifidobacterium breve. PhD thesis National University of Ireland, Cork, Cork, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pokusaeva K, O'Connell-Motherway M, Zomer A, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2009. Characterization of two novel alpha-glucosidases from Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:1135–1143. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02391-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Connell Motherway M, O'Driscoll J, Fitzgerald GF, Van Sinderen D. 2009. Overcoming the restriction barrier to plasmid transformation and targeted mutagenesis in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb Biotechnol 2:321–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2008.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Maze A, O'Connell-Motherway M, Fitzgerald G, Deutscher J, van Sinderen D. 2007. Identification and characterization of a fructose phosphotransferase system in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:545–553. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01496-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wells JM, Wilson PW, Le Page RWF. 1993. Improved cloning vectors and transformation procedure for Lactococcus lactis. J Appl Bacteriol 74:629–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb05195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Hijum S, de Jong A, Baerends R, Karsens H, Kramer N, Larsen R, den Hengst C, Albers C, Kok J, Kuipers O. 2005. A generally applicable validation scheme for the assessment of factors involved in reproducibility and quality of DNA-microarray data. BMC Genomics 6:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zomer A, Fernandez M, Kearney B, Fitzgerald GF, Ventura M, van Sinderen D. 2009. An interactive regulatory network controls stress response in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. J Bacteriol 191:7039–7049. doi: 10.1128/JB.00897-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pokusaeva K, Neves AR, Zomer A, O'Connell-Motherway M, MacSharry J, Curley P, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2010. Ribose utilization by the human commensal Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Microb Biotechnol 3:311–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2009.00152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mierau I, Kleerebezem M. 2005. 10 years of the nisin-controlled gene expression system (NICE) in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68:705–717. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Álvarez-Martín P, O'Connell-Motherway M, van Sinderen D, Mayo B. 2007. Functional analysis of the pBC1 replicon from Bifidobacterium catenulatum L48. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:1395–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Ruyter PG, Kuipers OP, de Vos WM. 1996. Controlled gene expression systems for Lactococcus lactis with the food-grade inducer nisin. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:3662–3667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamoen LW, Van Werkhoven AF, Bijlsma JJE, Dubnau D, Venema G. 1998. The competence transcription factor of Bacillus subtilis recognizes short A/T-rich sequences arranged in a unique, flexible pattern along the DNA helix. Genes Dev 12:1539–1550. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ventura M, Zink R, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. 2005. Gene structure and transcriptional organization of the dnaK operon of Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 and application of the operon in bifidobacterial tracing. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:487–500. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.1.487-500.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dierks T, Lecca MR, Schlotterhose P, Schmidt B, von Figura K. 1999. Sequence determinants directing conversion of cysteine to formylglycine in eukaryotic sulfatases. EMBO J 18:2084–2091. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sardiello M, Annunziata I, Roma G, Ballabio A. 2005. Sulfatases and sulfatase modifying factors: an exclusive and promiscuous relationship. Hum Mol Gen 14:3203–3217. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sofia HJ, Chen G, Hetzler BG, Reyes-Spindola JF, Miller NE. 2001. Radical SAM, a novel protein superfamily linking unresolved steps in familiar biosynthetic pathways with radical mechanisms: functional characterization using new analysis and information visualization methods. Nucleic Acids Res 29:1097–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bottacini F, O'Connell Motherway M, Kuczynski J, O'Connell K, Serafini F, Duranti S, Milani C, Turroni F, Lugli G, Zomer A, Zhurina D, Riedel C, Ventura M, van Sinderen D. 2014. Comparative genomics of the Bifidobacterium breve taxon. BMC Genomics 15:170. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Egan M, O'Connell Motherway M, Ventura M, van Sinderen D. 2014. Metabolism of sialic acid by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4414–4426. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01114-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Connell KJ, O'Connell Motherway M, Liedtke A, Fitzgerald GF, Ross RP, Stanton C, Zomer A, van Sinderen D. 2014. Transcription of two adjacent carbohydrate utilization gene clusters in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 is controlled by LacI- and repressor open reading frame kinase (ROK)-type regulators. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3604–3614. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00130-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Egan M, O'Connell Motherway M, van Sinderen D. 2015. A GntR-type transcriptional repressor controls sialic acid utilization in Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003. FEMS Microbiol Lett 362:1–9. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnu056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Conejo M, Thompson S, Miller B. 2010. Evolutionary bases of carbohydrate recognition and substrate discrimination in the ROK protein family. J Mol Evol 70:545–556. doi: 10.1007/s00239-010-9351-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uehara T, Park JT. 2004. The N-acetyl-d-glucosamine kinase of Escherichia coli and its role in murein recycling. J Bacteriol 186:7273–7279. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7273-7279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.White R. 1968. Control of amino sugar metabolism in Escherichia coli and isolation of mutants unable to degrade amino sugars. Biochem J 106:847–858. doi: 10.1042/bj1060847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nishimoto M, Kitaoka M. 2007. Identification of N-acetylhexosamine 1-kinase in the complete lacto-N-biose I/galacto-N-biose metabolic pathway in Bifidobacterium longum. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:6444–6449. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01425-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kitaoka M, Tian J, Nishimoto M. 2005. Novel putative galactose operon involving lacto-N-biose phosphorylase in Bifidobacterium longum. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3158–3162. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.3158-3162.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Egan M, O'Connell Motherway M, Kilcoyne M, Kane M, Joshi L, Ventura M, van Sinderen D. 2014. Cross-feeding by Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 during co-cultivation with Bifidobacterium bifidum PRL2010 in a mucin-based medium. BMC Microbiol 14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kurokawa K, Itoh T, Kuwahara T, Oshima K, Toh H, Toyoda A, Takami H, Morita H, Sharma VK, Srivastava TP, Taylor TD, Noguchi H, Mori H, Ogura Y, Ehrlich DS, Itoh K, Takagi T, Sakaki Y, Hayashi T, Hattori M. 2007. Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res 14:169–181. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schell M, Karmirantzou M, Snel B, Vilanova D, Berger B, Pessi G, Zwahlen M-C, Desiere F, Bork P, Delley M, Pridmore D, Arigoni F. 2002. The genome sequence of Bifidobacterium longum reflects its adaptation to the human gastrointestinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212527599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murooka Y, Ishibashi K, Yasumoto M, Sasaki M, Sugino H, Azakami H, Yamashita M. 1990. A sulfur- and tyramine-regulated Klebsiella aerogenes operon containing the arylsulfatase (atsA) gene and the atsB gene. J Bacteriol 172:2131–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wright DP, Knight CG, Parkar SG, Christie DL, Roberton AM. 2000. Cloning of a mucin-desulfating sulfatase gene from Prevotella strain RS2 and its expression using a Bacteroides recombinant system. J Bacteriol 182:3002–3007. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.11.3002-3007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Scardovi V, Trovatelli ID. 1965. The fructose-6-phosphate shunt as a peculiar pattern of hexose degradation in the genus Bifidobacterium. Ann Microbiol 15:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rho JH, Wright DP, Christie DL, Clinch K, Furneaux RH, Roberton AM. 2005. A novel mechanism for desulfation of mucin: identification and cloning of a mucin-desulfating glycosidase (sulfoglycosidase) from Prevotella strain RS2. J Bacteriol 187:1543–1551. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.5.1543-1551.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Turroni F, Milani C, Duranti S, Mancabelli L, Mangifesta M, Viappiani A, Lugli GA, Ferrario C, Gioiosa L, Ferrarini A, Li J, Palanza P, Delledonne M, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. 9 February 2016. Deciphering bifidobacterial-mediated metabolic interactions and their impact on gut microbiota by a multi-omics approach. ISME J doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cheng Q, Hwa V, Salyers AA. 1992. A locus that contributes to colonization of the intestinal tract by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron contains a single regulatory gene (chuR) that links two polysaccharide utilization pathways. J Bacteriol 174:7185–7193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sonnenburg ED, Sonnenburg JL, Manchester JK, Hansen EE, Chiang HC, Gordon JI. 2006. A hybrid two-component system protein of a prominent human gut symbiont couples glycan sensing in vivo to carbohydrate metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103:8834–8839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603249103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sonnenburg JL, Xu J, Leip DD, Chen C-H, Westover BP, Weatherford J, Buhler JD, Gordon JI. 2005. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science 307:1955–1959. doi: 10.1126/science.1109051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Robbe C, Capon C, Maes E, Rousset M, Zweibaum A, Zanetta J-P, Michalski J-C. 2003. Evidence of regio-specific glycosylation in human intestinal mucins: presence of an acidic gradient along the intestinal tract. J Biol Chem 278:46337–46348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Law J, Buist G, Haandrikman A, Kok J, Venema G, Leenhouts K. 1995. A system to generate chromosomal mutations in Lactococcus lactis which allows fast analysis of targeted genes. J Bacteriol 177:7011–7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.