Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a worldwide problem with serious health and economic repercussions. Since the 1940s, underuse, overuse, and misuse of antibiotics have had a significant environmental downside. Large amounts of antibiotics not fully metabolized after use in human and veterinary medicine, and other applications, are annually released into the environment. The result has been the development and dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria due to many years of selective pressure. Surveillance of AMR provides important information that helps in monitoring and understanding how resistance mechanisms develop and disseminate within different environments. Surveillance data is needed to inform clinical therapy decisions, to guide policy proposals, and to assess the impact of action plans to fight AMR. The Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit, based at the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro in Vila Real, Portugal, has recently completed 10 years of research surveying AMR in bacteria, mainly commensal indicator bacteria such as enterococci and Escherichia coli from the microbiota of different animals. Samples from more than 75 different sources have been accessed, from humans to food-producing animals, pets, and wild animals. The typical microbiological workflow involved phenotypic studies followed by molecular approaches. Throughout the decade, 4,017 samples were collected and over 5,000 bacterial isolates obtained. High levels of AMR to several antimicrobial classes have been reported, including to β-lactams, glycopeptides, tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, sulphonamides, and quinolones. Multi-resistant strains, some relevant to human and veterinary medicine like extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing E. coli and vancomycin-resistant enterococci, have been repeatedly isolated even in non-synanthropic animal species. Of particular relevance are reports of AMR bacteria in wildlife from natural reserves and endangered species. Future work awaits as this threatening yet unsolved problem persists.

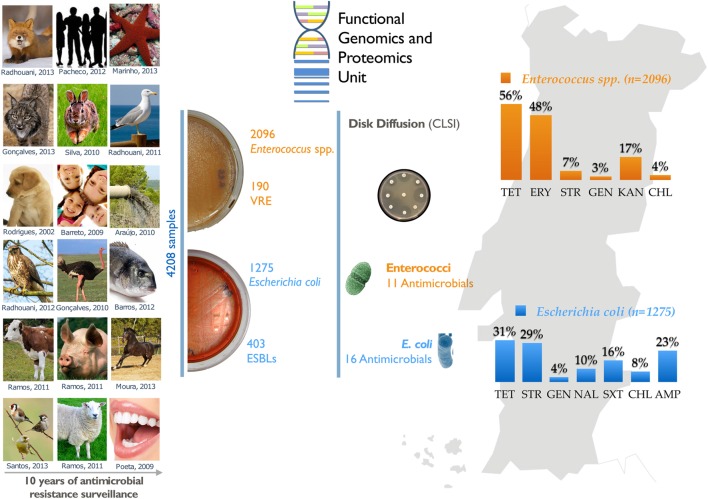

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT.

Summary diagram of the antimicrobial resistance surveillance work developed by the UTAD Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, surveillance, molecular microbiology, enterococci, Escherichia coli, wildlife

Introduction

The early XX century witnessed the beginning of the modern antibiotic era with the first true antibiotic treatment, an asfernamina (Salvarsan) discovered by Paul Ehrlich that was successfully used to treat Syphilis (Elsner, 1910; Aminov, 2010). The reign of antibiotics in clinical practice is commonly associated with the discovery of penicillin produced by the fungus Penicillium notatum by Fleming (2001). However, the first wide use of antibiotics was with a sulfanamide antibiotic powder carried by Second World War solders with effectiveness against a wide range of infections (Davenport, 2012). The use of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections became one of the main scientific accomplishments; leading many scientists to believe that the threat of infectious diseases had ended (Jones, 1999). However, this golden age has come to an end in recent decades as we have become aware of the evolution of antibiotic resistance in bacterial strains, particularly in pathogens developing resistance to an extensive range of antibiotics (Davies and Davies, 2010).

Antibiotics are small secondary metabolites, either naturally produced by microorganisms or chemically synthetized, to mediate competition among bacterial populations and communities (Allen et al., 2010; Cordero et al., 2012). Antibiotics are commonly found in the environment in sub-inhibitory concentrations diminishing the growth rate of competing populations rather than killing them. Natural or synthetic antibiotics can also act as signal molecules regulating expression of a large number of transcripts in different bacteria. Moreover, antimicrobial compounds might target self-regulation of growth, virulence, sporulation, motility, mutagenesis, stress response, phage induction, transformation, lateral gene transfer, intrachromosomal recombination, or biofilm formation (Goh et al., 2002; Yim et al., 2007; Baquero et al., 2013).

Currently, antibiotics available for consumption are produced either by microbial fermentation, semi- or full synthetically manufactured. Antibiotics cause bacterial death or inhibit growth by different mechanisms of action: (a) disrupting cell walls, e.g., β-lactam and glycopeptides; (b) targeting the protein synthetic machinery, e.g., macrolides, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, linezolid, and aminoglycosides; (c) affecting the synthesis of nucleic acids, e.g., fluoroquinolones and rifampin; (d) inhibiting metabolic pathways, e.g., sulphonamides and folic acid analogs; or (e) disrupting the membrane structure, e.g., polymyxins and daptomycin (Sengupta et al., 2013).

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) contributes to the homeostasis of microbial populations and communities by modulating the effect of naturally produced antibiotics (Cordero et al., 2012; Baquero et al., 2013). Human misuse of antibiotics has unbalanced this natural genetic system of resistance (Osterblad et al., 2001; Xi et al., 2009). In some developed countries, livestock alone represent about 50–80% of antibiotics consumption; crops, pets and aquaculture collectively account for an estimated 5%, and human therapy the remainder (Cully, 2014). The use of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine exerts a major selective pressure leading to the emergence and spread of resistance because about 30–90% of antibiotics used are not metabolized and are discarded basically unchanged (Sarmah et al., 2006). The period of time that an antibiotic takes to be degraded after release into the environment might influence how it spreads and accumulates. For instance, penicillins are easily degraded, while fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines persist for longer. Direct discharges from antibiotics industries into water effluents can be shockingly high, a reality in both developed and developing countries (Li et al., 2009; Joakim Larsson, 2014). Antibiotics are also released into the environment via agricultural application of manure and sewage water as fertilizers, and leakage from waste storage facilities (Sarmah et al., 2006; Le-Minh et al., 2010; Barrett, 2012).

The high concentration of antibiotics used prophylactically by humans might have led to contamination of human waste streams and exerted selection pressure on commensal and pathogenic bacteria. It is not surprising that non-metabolized antibiotics, resistance genes and mobile genetic elements are frequently detected in wastewaters and sewage treatment plants (Pellegrini et al., 2011). Often these compounds are not removed during sewage treatment to the extent that incidences of resistance genes are used as indicators of human impact on aquatic ecosystems (Zuccato et al., 2000; Araujo et al., 2010). Although antibiotics might be considered simply as chemical pollutants, genetic mobile elements are capable of self-replication and can be transmitted horizontally even between phylogenetically distant bacteria (Gillings and Stokes, 2012). Consequently, increased concentration of antibiotics in the environment raises the diversity and the abundance of resistance genes.

The consequences of antibiotic pollution are being actively examined, and there is an imperative need for novel strategies to curtail the release of antibiotics and bacteria from human sources (Baquero et al., 2013). Furthermore, the long-term consequences of spreading antibiotics and resistance genes cannot be predicted without quantitative analysis over suitable timescales (Chee-Sanford et al., 2009). The spread of AMR into the environment occurs not only through the contamination of natural resources but also through the food chain and direct contact between human and animals.

Currently, AMR has been reported for all antibiotic classes used both in human or veterinary medicine. An association between antibiotic use and clinical AMR proliferation has also been described (Skurnik et al., 2006; Pallecchi et al., 2008). AMR is now considered a major challenge requiring urgent action in the present to prevent a worldwide catastrophe in the future.

Portugal boasts some of the most diverse fauna and flora in Europe, and in relation to its size is considered one of the 25 biodiversity hotspots of the world (Pereira et al., 2004). Its farming systems are also numerous and varied. However, Portugal is at high risk of losing this diversity. With the mission of long-term surveillance of AMR in bacteria from different sources, the Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit, based at the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (Vila Real, Portugal), has recently completed a decade of unceasing research. Over the years, we have investigated the resistomes of several bacteria, mainly commensal indicator bacteria such as enterococci and Escherichia coli sampled from the microbiota of different animals or from other sources. Here, we present an overview of the resistance profiles of these bacteria in relation to where they were found.

AMR as a Public Health Concern

Antimicrobial resistance has become recognized as a major clinical and public health problem (Gillings, 2013). Every year about 25,000 patients perish in the European Union (EU) because of hospital-acquired resistant bacterial infection (ECDC, 2011). Likewise, in the United States of America (USA), infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria are more common among the population than cancer, with at least 2 million people infected every year, at least 23,000 of whom die (CDC, 2013). Besides the clinical consequences of AMR, there are also large societal costs. The number of new antibiotics coming to the market over the past three decades has dramatically declined as several pharmaceutical companies stopped searching for antibiotics in favor of other antimicrobial drugs (Spellberg et al., 2004; Walsh, 2013). When antimicrobial drugs are discovered and developed, it is imperative to understand and predict how resistance mechanisms might evolve in order to find a method to control dissemination (Walsh, 2013). Genome-scale research may offer insight into unknown mechanisms of AMR (Tenover, 2006; Rossolini and Thaller, 2010). This will then inform decisions on appropriate policies, surveillance, and control strategies. The ideal AMR surveillance system should be able to track long-term antibiotic resistance trends, regularly alert healthcare professionals to novel resistance profiles, identify emerging resistance patterns, and create an easy-access database for physicians and scientists (Jones, 1999). To avoid a crisis, governments must recognize the importance of this valuable resource and implement a wiser and more careful use of antibiotics, raising everyone’s awareness of this issue.

Investigating the zoonotic AMR problem in its full complexity requires the collection of many types of data. Identifying the most efficient points at which intervention can control AMR mainly depends on quality collaboration between all the stakeholders involved (Wegener, 2012). The One Health concept is a universal strategy for improving connections between stakeholders in all aspects of health for humans, animals and the environment. The aim is that the synergism achieved between interdisciplinary collaborations will push forward healthcare, accelerate biomedical research breakthroughs, increase the effectiveness of public health, extend scientific knowledge and improve clinical care. When properly implemented, millions of lives can be protected and saved in the near future (Pappaioanou and Spencer, 2008). The One Health initiative is therefore an ideal framework for addressing zoonotic transmission of AMR bacteria by monitoring and managing agricultural activities, food safety professionals, human and animal clinicians, environment and wildlife experts, while maintaining a global vision of the problem.

Resistome

The antibiotic resistome defines the pool of genes that contribute to an antibiotic resistance phenotype (D’Costa et al., 2006). Bacterial populations have exquisite mechanisms to transfer antibiotic resistance genes by horizontal transfer, mainly in densely populated microbial ecosystems. The human gut, for instance, offers ample opportunities for bacteria of different provenance to share genetic material, including the many antibiotic resistance genes harbored by gut microflora (van Schaik, 2015).

Currently, there is urgent focus on the natural resistome. A resistome database was set up in Liu and Pop (2009) and contains information on about 20,000 genes reported so far. Conclusions from several metagenomics approaches are that those 20,000 genes are just a small portion of all resistomes, since other genes with different purposes not directly related to antibiotic resistance may be implicated (Gillings, 2013). Recently, a new bioinformatics platform has been developed, the comprehensive antibiotic research database (CARD), which integrates molecular and sequence data allowing a fast identification of putative antibiotic resistance genes in newly annotated genome sequences (McArthur et al., 2013). Environmental and human associated microbial communities have been shown to harbor distinct resistomes, suggesting that antibiotic resistance functions are mainly constrained by ecology (Gibson et al., 2015). However, to date, studies investigating the roles of antibiotics and AMR outside of the clinical environment are scarce. To know more about resistome composition and the dynamics among AMR genes, new studies should be performed on AMR communities in the environment.

AMR Surveillance in Indicator Bacteria

Living organisms are defined by the genes they possess, while the control of expression of this gene set, both temporally and in response to the environment, determines whether an organism can survive changing conditions and compete for the resources it needs to reproduce. Changes to a bacterial genome are likely to threaten the microbe’s ability to survive, but acquisition of new genes may enhance its chances of thriving by allowing growth in a formerly hostile environment. If a pathogenic bacteria gains resistance genes it is more likely to survive in the presence of antimicrobials that would otherwise eradicate it, thus compromising clinical treatments. Bacterial genomes are dynamic entities evolving through several processes, including intrachromosome genetic rearrangements, gene duplication, gene loss and gene gain by lateral gene transfer, and several other chemical and genetic factors can trigger changes by locally altering nucleotide sequences (Lawrence, 2005). AMR strains emerge and spread as a combined result of intensive antibiotics use and bacterial genetic transfer, and the incidences of resistant bacteria from diverse habitats have been increasing (Coque et al., 2008).

Recently, several pathogens have been reported as being multidrug-resistant (MDR) and believed to be ‘unbeatable’ (Grundmann et al., 2006). Incidences of MDR strains of Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Salmonella, and Enterococcus are of international concern and have been reported thoroughly by global health organizations (ECDC, 2013; WHO, 2014). Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is one of the main causes of AMR associated clinical infections. Resistant isolates are still being reported at a high rate, as in Portugal where MRSA is recovered from more than 50% of isolates from humans (ECDC, 2013). In 2011, the percentage of E. coli isolates resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, through production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs), ranged from 3 to 36% in Europe. Over the last 4 years, MDR in E. coli has been reported to be on the increase (ECDC, 2013). Also on European territory, enterococci resistant to high-level aminoglycosides (25–50% of recovered isolates) and vancomycin (VRE) (less than 5% of isolates) have been reported with some countries noting an increase (ECDC, 2013). Salmonella are considered potential sources of zoonosis. MDR Salmonella strains are often recovered from human and animal isolates in Europe, with high incidence in children (ECDC, 2013).

Human and animal commensal gastrointestinal bacteria are continuously subject to diverse antimicrobial pressures (Levy and Marshall, 2004). Resistant strains may act as reservoirs of resistance genes that can easily be spread to pathogenic strains (Allen et al., 2013). The potential pathogens E. coli and enterococci are commonly used as indicators of the selection pressure and AMR evolution through the environment (Radhouani et al., 2014).

Escherichia coli are facultative anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the Enterobacteriaceae family. As a commensal bacterium E. coli colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of humans and animals, but it is found ubiquitously in soil, plants, vegetables and water (van den Bogaard and Stobberingh, 2000). E. coli is a potential pathogen and the leading cause of human urinary tract infection, bacteraemia and gastroenteritis, among many other infections that require therapeutic intervention (Fluit et al., 2001; Kaper et al., 2004). E. coli has an outstanding capacity to acquire and transfer antibiotic resistance genes from or to other bacteria, which can later be disseminated from humans to animals and to the natural environment, and vice versa (Teuber, 1999). AMR E. coli strains, particularly those resistant to important antibiotics, have been increasing (Collignon, 2009).

Likewise, Enterococcus are commensal bacteria from the intestinal flora of humans and animals, and are frequently monitored as indicators of fecal contamination of food products (Teuber and Perreten, 2000; Ramos et al., 2012). Enterococci are facultative anaerobes capable of persisting in extreme conditions caused by temperature and pH variations, dehydration, and oxidative stress. In the last two decades they have become dangerous nosocomial pathogens, persisting in hospital environments where selective pressure from the presence of antibiotics improves their resistome (Franz et al., 2011; Arias and Murray, 2012). Enterococci can cause urinary tract, wound and intra-abdominal infections, endocarditis, and bacteraemia. Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are the major species responsible for enterococci infections. Enterococci are intrinsically resistant to some antibiotics (β-lactams and aminoglycosides) and some species have specific AMR, such as E. faecalis to lincosamides and streptogramins A, and Enterococcus gallinarum and E. casseliflavus to vancomycin. They can also easily exchange resistance genes with other bacteria. Use of avoparcin, a glycopeptide antibiotic chemically similar to vancomycin, as an animal feed additive in Europe, and of high amounts of vancomycin in USA hospitals has led to the spread of VRE in animals, humans, food, and the environment (Kirst et al., 1998; Wegener, 1998). However, banning avoparcin in 2006 has not been sufficient to eradicate the AMR mechanisms present in bacteria and some VRE still persist in animals and the environment (Poeta et al., 2007b; Araujo et al., 2010; Ramos et al., 2012).

Compilation of UTAD AMR Surveillance Data

Antibiotic prescribing practices in the EU differ widely, and the introduction of standardization would be one way to monitor use more closely and possibly reduce the emergence of resistant bacteria. The antimicrobials market has been increasing with an average annual growth of 6.6% between 2005 and 2011. Worldwide demand for antibiotics is conjectured to reach about €34.1 billion in 2016. Currently, the market is dominated by aminoglycosides, which account for 79% of demand, while penicillins account for 8%, erythromycin 7%, tetracyclines 4%, and chloramphenicol 1%. Market expansion is expected to slow down to 4.6% in coming years (GR & DS, 2012). Between 2000 and 2010, consumption of antibiotic drugs increased by 36% (from 54 billion standard units to 73 billion standard units). The greatest increase was in low- and middle-income countries, but in general, high-income countries still use more antibiotics per capita (Van Boeckel et al., 2014). Portugal is in the top 10 European countries with the greatest consumption of antibiotics, at around 21–25 doses per 1,000 habitants each year (Hede, 2014). Nonetheless, exposure to antibiotics it is not only of antibiotic consumption through prescribed human treatments but also by their use in animal production. The antibiotic environmental contamination can contribute further to the increased emergence of resistance in pathogenic and environmental bacteria. The antibiotics used in animal production may be excreted directly into the environment, or accumulate in manure which could later be spread on land as fertilizer (Almeida et al., 2014). The global total consumption of antibiotics in livestock was estimated in 2010 to be around 63,151 tons and it is project to rise 67% by 2030. Increase driven by the growth in consumer demand for livestock products in middle-income countries and a shift to large-scale farms where antimicrobials are used routinely (Van Boeckel et al., 2014).

The Portuguese annual amount of antibiotics used in human and animal consumption was discussed in a report with data from 2010 to 2011. A first comparison of the antibiotic usage in human and veterinary medicine in Portugal indicates that two-thirds of the consumed antibiotics are used in veterinary medicine whereas the rest one-third in human medicine. For human medicine antibiotic prescription increased 4.5 tons (81.4–85.9 tons). In these two registered years, the annual amount of the different antibiotic groups was markedly larger for penicillins, which alone accounted for more than 65.0%, followed by quinolones (13.0%), macrolides (7.0%), cephalosporins (6.0%), and sulfonamides (5.0%). In veterinary medicine the annual amount of antibiotics sold was 179 tons in 2010 and 163 tons in 2011. Tetracyclines and penicillins were the most sold therapeutic solutions for the both years (Almeida et al., 2014).

Although it has been registered a decrease in the use of antibiotics in Portugal, their consumption and use is still high. Surveying AMR trends among bacteria is necessary to inform risk analyses and guide public policy. Over one decade at University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD), the antimicrobial profiles of indicator bacteria E. coli (Table 1) and enterococci (Table 2) have been studied in samples isolated from more than 75 different sources in Portugal. Figure 1 summarizes the data according to the four groups of sources from which samples were collected: humans, pets, food-producing animals, and wild animals.

Table 1.

Description of all sources of Escherichia coli isolates analyzed in a decade of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance in Portugal by the UTAD Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit.

| Sampling group | Sample source | Recovered samples (n = 1,841 | Recovered isolates (n = 1,275) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pets | Dogs and cats | 75 | 144 | Costa et al., 2008 |

| Humans | Children | 118 | 92 | Barreto et al., 2009 |

| Oral hygiene patients | 46 | 2 | Poeta et al., 2009 | |

| Food-producing animals | Pigs, cattle, and sheep | 198 | 192 | Ramos et al., 2012 |

| Wild animals | Diarrheic rabbits | 52 | 52 | Poeta et al., 2010 |

| Wild rabbits | 77 | 44 | Silva et al., 2010 | |

| Buzzards | 42 | 36 | Radhouani et al., 2012 | |

| Red foxes | 52 | 22 | Radhouani et al., 2013 | |

| Several wild animals | 72 | 56 | Costa et al., 2006 | |

| Seagulls | 53 | 53 | Radhouani et al., 2009 | |

| Lusitano horses | 90 | 71 | Moura et al., 2010 | |

| Iberian wolf | 237 | 195 | Goncalves et al., 2013a | |

| Iberian lynx | 27 | 18 | Goncalves et al., 2012 | |

| Iberian lynx | 98 | 96 | Goncalves et al., 2013b | |

| Echinoderms | 250 | 10 | Marinho et al., 2013 | |

| Wild birds | 218 | 115 | Santos et al., 2013 | |

| Wild rabbits | 136 | 77 | Silva et al., 2010 |

Table 2.

Description of all sources of Enterococcus spp. isolates analyzed in a decade of AMR surveillance in Portugal by the UTAD Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit.

| Sampling group | Sample source | Recovered samples (n = 2,730) | Recovered isolates (n = 2,287) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pets | Dogs and cats | 104 | 104 | Rodrigues et al., 2001 |

| Dogs and cats | 220 | 142 | Poeta et al., 2005a | |

| Humans | Humans | 220 | 146 | Poeta et al., 2005a |

| Children | 118 | 101 | Barreto et al., 2009 | |

| Oral hygiene patients | 46 | 8 | Poeta et al., 2009 | |

| Food-producing animals | Poultry | 220 | 152 | Poeta et al., 2005a |

| Pigs, cattle, and sheep | 198 | 194 | Ramos et al., 2012 | |

| Wild animals | Wild animals | 77 | 140 | Poeta et al., 2005b |

| Wild boars | 67 | 134 | Poeta et al., 2007b; Silva et al., 2010 | |

| Wild rabbit | 77 | 64 | Silva et al., 2010 | |

| Gilthead seabream | 118 | 73 | Barros et al., 2011 | |

| Seagulls | 57 | 54 | Radhouani et al., 2011 | |

| Buzzards | 42 | 31 | Radhouani et al., 2012 | |

| Iberian wolf | 237 | 227 | Goncalves et al., 2013a | |

| Iberian lynx | 30 | 27 | Goncalves et al., 2011 | |

| Iberian lynx | 98 | 96 | Goncalves et al., 2013b | |

| Echinoderms | 250 | 144 | Marinho et al., 2013 | |

| Lusitano horses | 90 | 71 | Moura et al., 2010 | |

| Red foxes | 52 | 50 | Radhouani et al., 2013; Santos et al., 2013 | |

| Wild birds | 218 | 138 | Santos et al., 2013 |

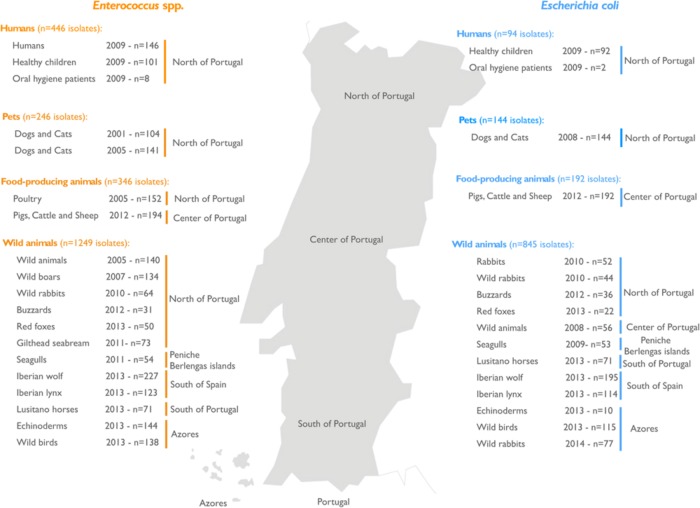

FIGURE 1.

Geographical distribution in Portugal showing the sources of samples containing bacterial isolates. The number and provenance of samples containing enterococci (orange) and Escherichia coli (blue) are shown. Both types of bacteria were frequently isolated from several samples from humans, pets, food-producing animals, and wild animals.

The fecal samples used in all studies, either from Human or animal origin, were obtained following similar guidelines. The fecal samples (one per animal) were recovered from patients (in the case of human studies) and directly from the intestinal tract in the animal studies. Samples were transported in Cary-Blair medium from the place of recovery to the Centre of Studies of Animal and Veterinary Sciences (CECAV) facilities for processing. For E. coli selection, fecal samples were seeded onto Levine agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. One colony per sample with typical E. coli morphology was selected and identified by classical biochemical methods (Gram-staining, catalase, oxidase, indol, Methyl-Red, Voges-Proskauer, citrate, urease, and triple sugar iron), and by the API 20E system (BioMerieux, La Balme Les Grottes, France). As for the enterococcal isolation, fecal samples were sampled onto Slanetz-Bartley agar plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. One colony with typical enterococcal morphology were identified to the genus level by cultural characteristics, Gram staining, catalase test, and bile-aesculin reaction. Antibiotic susceptibility tests were made by the disk diffusion method following CLSI recommendations. 16 antibiotics were tested against E. coli isolates: ampicillin (10 mg), amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (20 mg + 10 mg), cefoxitin (30 mg), cefotaxime (30 mg), ceftazidime (30 mg), aztreonam (30 mg), imipenem (10 mg), gentamicin (10 mg), amikacin (30 mg), tobramycin (10 mg), streptomycin (10 mg), nalidixic acid (30 mg), ciprofloxacin (5 mg), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (1.25 mg + 23.75 mg), tetracycline (30 mg), and chloramphenicol (30 mg). The identification of phylogenetic groups was performed as described by Clermont E. coli phylo-typing method (Clermont et al., 2000). In the case of enterococci, the isolates were tested for 11 antibiotics: [vancomycin (30 μg), teicoplanin (30 μg), Ampicillin (10 μg), streptomycin (300 μg), gentamicin (120 μg), kanamycin (120 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), erythromycin (15 μg), quinupristin-dalfopristin (15 μg), and ciprofloxacin (5 μg)], also by the disk diffusion method. Species identification was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using primers and conditions for the different enterococcal species. E. coli and enterococci isolates with resistance to one or more antibiotics were selected for the characterization of antibiotic-resistance genes. Their DNA was extracted and tested by PCR with specific primers already published. E. coli resistant isolates were screened for the following resistance genes: blaTEM and blaSHV (in ampicillin-resistant isolates); tetA and tetB (in tetracycline resistant isolates); aadA, aadA5, strA, and strB (in streptomycin-resistant isolates); and sul1, sul2, and sul3 (in sulfa-methoxazoletrimethoprim-resistant isolates). Also, the presence of intI, intI2 and qacED + sul1 genes was analyzed by PCR in all sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim-resistant isolates. On the other hand, enterococci resistant isolates were tested by PCR for detection of the following resistance genes: erm(B) and erm(C) (in erythromycin-resistant isolates), tet(M) and tet(L) (in tetracycline-resistant isolates), aph(3′)-IIIA (in kanamycin-resistant isolates), aac(6′)-aph(2′′) (in gentamicin-resistant isolates), ant(6)-Ia (in streptomycin-resistant isolates), vat(D) and vat(E) (in quinupristin/dalfopristin-resistant isolates), and van(A) (in vancomycin-resistant isolates). Positive and negative controls were used in all PCR reactions, from the strain collection of the University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (Portugal).

In this collation of data, a total of 1,841 samples were collected and screened for E. coli. The overall E. coli recovery rate was 69.26% (Table 1), but rates were different among the different sampling groups, ranging from 96.97% in fecal samples from food-producing animals down to 52.08% in fecal samples from pets. These are higher percentages than the E. coli recovery rate (51%) from humans, domestic and food-producing animal feces, or sewage and surface water in the USA (Sayah et al., 2005). A total of 2,539 samples were screened for enterococci, and a total of 2,096 enterococci isolates were obtained giving a recovery rate of 78.1% (Table 2). Rates of recovery from the four sampling groups were similar (75.93% for pet fecal samples, 66% for human samples, 82.78% for fecal samples from food-producing animals; and 88.39% for fecal samples from wild animals). These rates are very similar to previously reported rates (77%) of enterococci recovery from human, animal and environmental samples in several European countries (Kuhn et al., 2003).

Escherichia coli Data Description

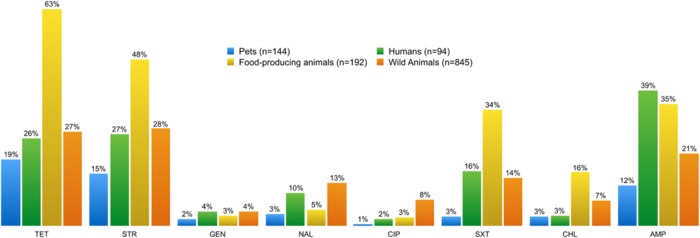

Phenotypic and genotypic studies were used to assess the AMR profile of the isolates. Figures 2 and 3 summarize the results of tests for antibiotic resistance and identification of associated resistance genes in E. coli isolates, comparing the four different sample groups described in Table 1. Resistance to all the antibiotics tested was found among the samples. Remarkably, E. coli from food-producing animals showed higher rates of resistance to tetracycline, streptomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol than E. coli from humans (Figure 2). Indeed fecal E. coli isolates recovered from food-producing animals all across Europe have shown a high prevalence of resistance to these antimicrobial agents (Guerra et al., 2003; Enne et al., 2008; Lapierre et al., 2008). Despite the ban on chloramphenicol use in farming in Europe since 1994, food-producing animals still carry resistant strains. Regular and multipurpose use of antibiotics, dissemination of resistant bacteria via fecal contamination and intensive animal production have turned husbandry facilities into important reservoirs of AMR bacteria (van den Bogaard and Stobberingh, 2000). High levels of resistance to tetracycline and streptomycin have been found in bacteria from wild animals. The high prevalence of tetracycline resistance in either E. coli or enterococci found in different wild animal species might be related to the recurrent use of this antibiotic in veterinary medicine. The same may be true of the prevalence of resistance to erythromycin, ampicillin, aminoglycosides, and quinolones. One of the main routes of transmission of resistant strains and resistant genes has been shown to be through the food chain (Aarestrup et al., 2008). Antibiotics can be administered to animals to treat (therapy) or prevent (prophylaxis or metaphylaxis) illness and in the past were also used to promote animal growth. Several classes of antimicrobial agents are frequently used in veterinary medicine. A 2013 report showed that in 2011 in 25 countries from the EU/European Economic Area, tetracyclines (37%) were the most sold antimicrobial class for administering to food-producing species, followed by penicillins (23%), sulfonamides (11%), macrolides (8%), lincosamides (2.9%), aminoglycosides (2%), trimethoprim (1.6%), and fluoroquinolones (1.6%) (European Medicines Agency, 2013). Antimicrobial use in veterinary medicine and AMR in commensal E. coli from various food-producing animals has indeed been correlated (Chantziaras et al., 2014). Ampicillin is a β-lactam used as a farm animal growth promoter (Sayah et al., 2005). E. coli from human samples differ from E. coli from other sampling groups in terms of their ampicillin resistance, which is of particular importance considering that ampicillin is a first-line antibiotic commonly effective against a broad spectrum of pathogens.

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of phenotypic antibiotic resistance detected in enterococci and E. coli isolates from each of the four sampling groups. The resistance profile of enterococci from food-producing animals is distinct from those of the other sampling groups, showing the highest resistance to tetracycline, streptomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and chloramphenicol. Enterococci from pets displayed the lowest resistance profile to all tested antibiotics. TET, tetracycline; STR, streptomycin; GEN, gentamicin; NAL, nalidixic acid; CIP, ciproflaxin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; CHL, chloramphenicol; AMP, ampicillin.

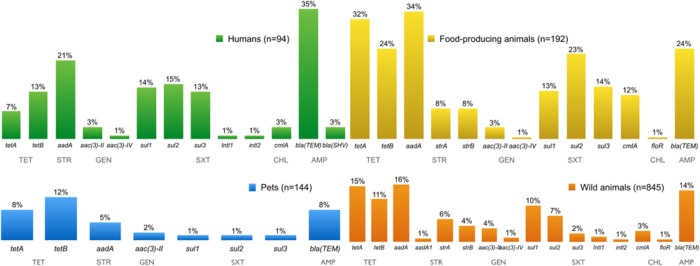

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes detected in E. coli resistant isolates from all sources over a decade.

Comparing AMR E. coli from independent sources, several genes conferring AMR were found in resistant isolates (Figure 3). Fourteen different tet genes have been reported in Gram-negative bacteria, encoding proteins active in the three mechanisms of tetracycline resistance, namely an efflux pump, ribosomal protection, or direct enzymatic inactivation of the antibiotic. The resistance genes tetA and tetB confer resistance to tetracycline, and were found at similar frequencies in all different sources of resistant E. coli. However, tetA and tetB are more likely to be associated with tetracycline resistance in E. coli isolated from human and animal samples (Bryan et al., 2004).

The streptomycin resistance genes aadA, strA, strB, and aadA1 were found, in descending order of frequency, in resistant E. coli. The strA and strB genes encode streptomycin-inactivating enzymes which confer streptomycin resistance in many Gram-negative bacteria distributed worldwide. The aadA gene encodes an adenylylation enzyme that modifies streptomycin and, in the aadA1 gene cassette, is often found in streptomycin-resistant E. coli strains from human, animal, and food samples (Saenz et al., 2004).

Gentamicin resistance genes aac(3)-II and aac(3)-IV were present in resistant E. coli isolates. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-resistant E. coli isolates had sul1, sul2 and/or sul3 genes, and the integrons intI1 and intI2 genes, encoding class 1 and class 2 integrases, respectively. The sul1, sul2, and sul3 genes each encode dihydropteroate synthases to confer plasmid-mediated resistance to sulphonamides (Perreten and Boerlin, 2003; Skold, 2010). The sul1 gene is frequently found linked to other resistance genes in class 1 integrons, while sul2 is normally located on small plasmids of the incQ incompatibility group, or other small plasmids represented by pBP1 (Skold, 2010). The sul1 and sul2 genes have been regularly found at similar frequencies among sulphonamide resistant Gram-negative clinical isolates. However, an increase in prevalence of the sul2 gene has been observed. The association between sul2 and multiresistance plasmids, which may be co-selected through the use of other antimicrobial agents, might explain the increased prevalence (Blahna et al., 2006; Frank et al., 2007).

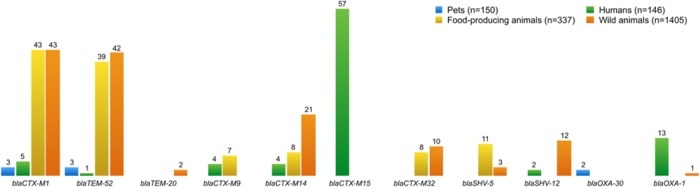

Chloramphenicol resistant E. coli isolates have the resistance genes cmlA and floR, both coding efflux pumps that reduce the intracellular concentration of antibiotics by exporting different molecules (Saenz et al., 2004). Some infections are difficult to treat because of bacterial expression of multidrug efflux systems causing resistance. ESBLs confer resistance to penicillins and most cephalosporins, including third-generation cephalosporins, and more than 700 different ESBLs have now been described (van Duijn et al., 2011). A total of 403 isolates of ESBL-producing E. coli were obtained from all four sampling groups: humans (n = 138), pets (n = 8), food-producing animals (n = 116), and wild animals (n = 141). Figure 4 shows all genes encoding ESBLs that were detected in these isolates. The most prevalent ESBL genes were blaCTX-M-1 (n = 94) and blaTEM-52 (n = 85), specifically isolated from E. coli from food-producing and wild animals, followed by the blaCTX-M-32 (n = 57) gene found in isolates from human samples. The mechanisms of resistance against one antibiotic might not be exclusive, and activity may be exhibited against other similar compounds. For instance, it has been proven that mutations in the genes encoding penicillin-inactivating enzymes (e.g., TEM and SHV) can also confer resistance to third-generation cephalosporins or β-lactamase inhibitors (Martinez et al., 2007).

FIGURE 4.

Number of ESBL-producing E. coli and resistance genes present in all isolates from different groups. blaCTX-M15 was the most frequent ESBL gene recovered from E. coli, followed by blaCTX-M-1 and blaTEM-52. Otherwise, blaTEM-20, blaOXA-30, and blaCTX-M-9 genes were found in a few ESBL-producing E. coli.

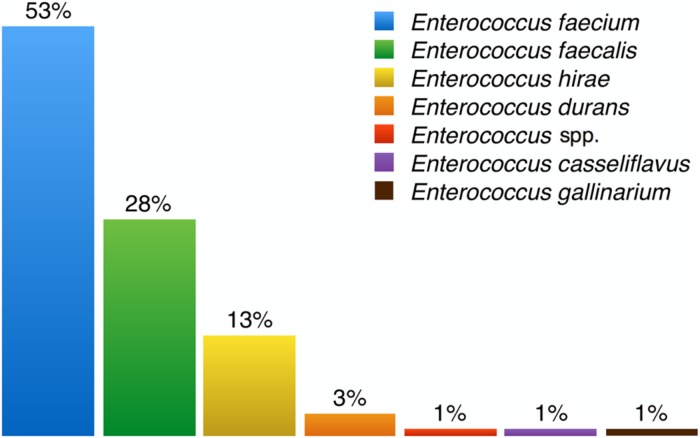

Enterococci Data Description

Several species of enterococci were recovered from different environments, with some being more common than others depending on the source of the sample. Figure 5 summarizes all data on enterococci species prevalence reported in the publications listed in Table 2. E. faecalis is the most common enterococcal species in human stools and the most frequent cause of clinical infection. The natural resistance of this species to penicillin, cephalosporins, and quinolones has contributed to its emergence as a cause of nosocomial infection. However, E. faecium is inherently more antibiotic-resistant and has also gradually become a major hospital pathogen (French, 2010; Radimersky et al., 2010). Overall from all the enterococci species we isolated, E. faecium was by far the most frequently recovered (52.9%), followed by E. faecalis, E. hirae, E. durans, E. casseliflavus, and E. gallinarum (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Percentages of enterococci species isolated from samples. Enterococcus faecium is the most frequently isolated enterococci species among all recovered samples and Enterococcus gallinarum the least.

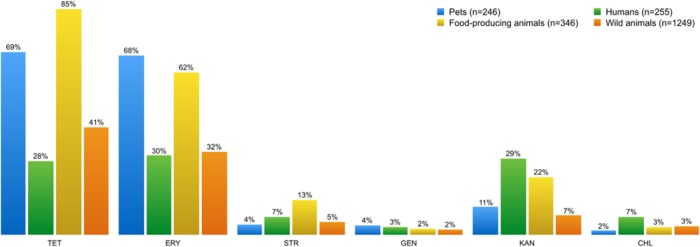

Figures 6 and 7 show the collated antibiotic resistance data of enterococci isolates from the different sources listed in Table 2. Remarkably, more enterococci from the group of food-producing animals were resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin than from the human group (Figure 6). Many enterococci resistant to tetracycline and erythromycin were also found in the wild animals group. Enterococci resistant to kanamycin and chloramphenicol were more frequent in samples from humans than from other sources.

FIGURE 6.

Percentage of phenotypic antibiotic resistance detected in Enterococcus spp. isolates from each of the four sampling groups. Enterococci isolates showed high resistance levels to tetracycline and erythromycin, regardless of the source. However, food-producing animals and pets stand out from the other sampling groups. Streptomycin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol-resistant enterococci are more frequent in samples from humans than from other sources. TET, tetracycline; ERY, erythromycin; STR, streptomycin; GEN, gentamicin, KAN, kanamycin; CHL, chloramphenicol.

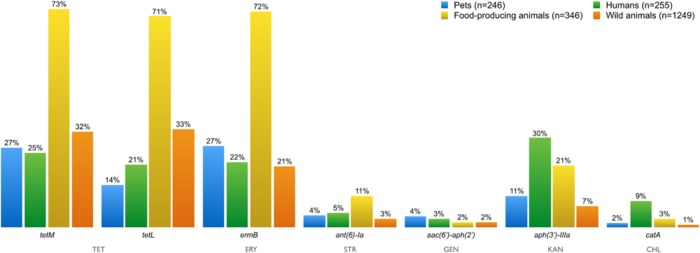

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of AMR genes detected in resistant Enterococci isolates from all sources over a decade. Resistance genes tet(M)/tet(L), erm(B), ant(6)-Ia, aac(6′)-aph(2′), aph(3′)-IIIA, and catA were present in enterococci isolates resistant to tetracycline, erythromycin, streptomycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol, respectively. TET, tetracycline; ERY, erythromycin; STR, streptomycin; GEN, gentamicin; KAN, kanamycin, CHL, chloramphenicol.

The distribution of AMR genes in the different sampling groups is illustrated in Figure 7. The tetM and tetL genes are associated with the tetracycline-resistance phenotype in enterococci. Tetracycline resistance due to TetL efflux proteins has been becoming more frequently reported among Gram-positive bacteria from animal sources (Figueiredo et al., 2009; Radhouani et al., 2010).

Erythromycin-resistance in enterococci is usually associated with the presence of the ermB gene. The ermB and tetM genes have been frequently identified together in the same isolate, probably because of they both occur in the mobile conjugative transposon Tn1545, prevalent in clinically important Gram-positive bacteria (De Leener et al., 2004). The resistance genes ant(6)-Ia, aac(6′)-aph(2′), aph(3′)-IIIA and catA were present in enterococci isolates resistant to streptomycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, and chloramphenicol, respectively. Resistance to all tested antibiotics has been showed in isolates from all groups.

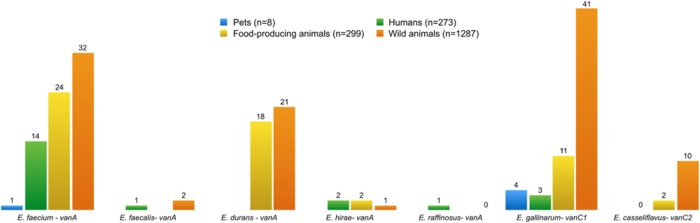

The presence of VRE isolates was noted in all four groups (Figure 8): humans (n = 21), pets (n = 5), food-producing animals (n = 57), and wild animals (n = 107). The presence of VRE isolates in diverse samples from Portugal is likely to be related to the use of avoparcin to promote growth of food animals in Europe since the 1970s until its prohibition in 2006. VRE was first characterized in Uttley et al. (1988), and has been repeatedly isolated since then from several sources. Many antimicrobials used in food animals belong to the same classes as those used in humans, leading to concerns about cross-resistance (Furuya and Lowy, 2006). For instance, vancomycin is still the most widely used antibiotic to treat serious infections like MRSA. Vancomycin resistance has emerged in S. aureus through acquisition of the vanA gene from VRE (Chang et al., 2003). It is important therefore to highlight the higher number of vancomycin resistant determinants found in wild animals compared to humans. In Europe, spread from animals to humans appears to have occurred outside hospital facilities, which explains why VRE is more commonly found in the environment than in the community (Furuya and Lowy, 2006).

FIGURE 8.

Number of vancomycin-resistant enterococci species, and resistance genes present in all isolates from different groups. E. gallinarum and E. casseliflavus are intrinsically resistant to vancomycin, and harbor the genes vanC1 and vanC2, respectively, in their genome.

Conclusion

Generalized use of antibiotics by humans is a recent addition to the natural and ancient process of antibiotic production and resistance evolution that still occurs on a global scale in the soil (Woolhouse et al., 2015). The main attributed cause of the rise and spread of AMR is the extensive clinical use of antibiotics in both human and veterinary medicine (Levy, 2001). However, antibiotic use in veterinary medicine alone does not explain the spread and persistence of AMR bacteria in animal populations in which the antibiotic use is discontinued or else is very sporadic or limited like in wildlife. AMR does not have borders, so it can freely cross through several populations, and homologous resistance genes have been reported in bacteria from pathogens, normal flora and soil. Farm animals are a significant factor in this system and they are still exposed to large amounts of antibiotics and act as reservoirs of many resistance genes. Other risk factors such as antibiotic residues in the environment and AMR gene dissemination in different human and animal populations also have an impact on the AMR levels (Alali et al., 2009). We are currently facing the potential loss of antimicrobial therapy, so it is essential to continue tracking AMR.

Future Perspectives

Human use of antibiotics for medicine and agriculture may have consequences far beyond their intended applications. The environment is a major reservoir of resistant organisms and antibiotic drugs freely circulating; though not much is known about the antibiotic resistome, shading their hypothetical impact on clinically important bacteria (Allen et al., 2010). Several resistance genes have been reported in distinct bacterial species, from diverse sources (Poeta et al., 2007a; Pallecchi et al., 2008; Gillings and Stokes, 2012). Nonetheless, more studies using standardized methods are required to recognize roles and patterns of antibiotic resistance genes in microbial communities. In the meantime, it is important to moderate the use of antimicrobials and restrain the rise and dissemination of AMR bacteria, so the management of emerging zoonotic diseases and their impacts might be forecasted (Allen et al., 2010). The foreseen decline in antibiotics effectiveness and the current lack of new antimicrobials on the horizon to replace those that become ineffective brings added urgency to the protection of the efficacy of existing drugs (Carlet, 2012; WHO, 2014). Meanwhile, omics approaches to generate molecular data on AMR mechanisms will continue to be the foundation of our work at the Functional Genomics and Proteomics Unit at UTAD.

Author Contributions

CM and TS wrote the manuscript. AG, PP, and GI helped interpret compiled data. GI conceived the review. All the authors reviewed and contributed to the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aarestrup F. M., Wegener H. C., Collignon P. (2008). Resistance in bacteria of the food chain: epidemiology and control strategies. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6 733–750. 10.1586/14787210.6.5.733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alali W. Q., Scott H. M., Christian K. L., Fajt V. R., Harvey R. B., Lawhorn D. B. (2009). Relationship between level of antibiotic use and resistance among Escherichia coli isolates from integrated multi-site cohorts of humans and swine. Prev. Vet. Med. 90 160–167. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2009.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen H. K., Donato J., Wang H. H., Cloud-Hansen K. A., Davies J., Handelsman J. (2010). Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8 251–259. 10.1038/nrmicro2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen S. E., Janecko N., Pearl D. L., Boerlin P., Reid-Smith R. J., Jardine C. M. (2013). Comparison of Escherichia coli recovery and antimicrobial resistance in cecal, colon, and fecal samples collected from wild house mice (Mus musculus). J. Wildl. Dis. 49 432–436. 10.7589/2012-05-142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida A., Duarte S., Nunes R., Rocha H., Pena A., Meisel L. (2014). Human and veterinary antibiotics used in Portugal—a ranking for ecosurveillance. Toxics 2 188–225. 10.3390/toxics2020188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov R. I. (2010). A brief history of the antibiotic era: lessons learned and challenges for the future. Front. Microbiol. 1:134 10.3389/fmicb.2010.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo C., Torres C., Silva N., Carneiro C., Goncalves A., Radhouani H., et al. (2010). Vancomycin-resistant enterococci from Portuguese wastewater treatment plants. J. Basic Microbiol. 50 605–609. 10.1002/jobm.201000102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias C. A., Murray B. E. (2012). The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10 266–278. 10.1038/nrmicro2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquero F., Tedim A. P., Coque T. M. (2013). Antibiotic resistance shaping multi-level population biology of bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 4:15 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto A., Guimaraes B., Radhouani H., Araujo C., Goncalves A., Gaspar E., et al. (2009). Detection of antibiotic resistant E. coli and Enterococcus spp. in stool of healthy growing children in Portugal. J. Basic Microbiol. 49 503–512. 10.1002/jobm.200900124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett J. R. (2012). Preventing antibiotic resistance in the wild: a new end point for environmental risk assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 120 a321 10.1289/ehp.120-a321a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros J., Igrejas G., Andrade M., Radhouani H., Lopez M., Torres C., et al. (2011). Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) carrying antibiotic resistant enterococci. A potential bioindicator of marine contamination? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 62 1245–1248. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blahna M. T., Zalewski C. A., Reuer J., Kahlmeter G., Foxman B., Marrs C. F. (2006). The role of horizontal gene transfer in the spread of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance among uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Europe and Canada. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57 666–672. 10.1093/jac/dkl020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan A., Shapir N., Sadowsky M. J. (2004). Frequency and distribution of tetracycline resistance genes in genetically diverse, nonselected, and nonclinical Escherichia coli strains isolated from diverse human and animal sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 2503–2507. 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2503-2507.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlet J. (2012). World Alliance against antibiotic resistance (WAAR): safeguarding antibiotics. Intensive Care Med. 38 1723–1724. 10.1007/s00134-012-2643-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC (ed.) (2013). Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Sievert D. M., Hageman J. C., Boulton M. L., Tenover F. C., Downes F. P., et al. (2003). Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 348 1342–1347. 10.1056/NEJMoa025025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantziaras I., Boyen F., Callens B., Dewulf J. (2014). Correlation between veterinary antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in food-producing animals: a report on seven countries. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 69 827–834. 10.1093/jac/dkt443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chee-Sanford J. C., Mackie R. I., Koike S., Krapac I. G., Lin Y. F., Yannarell A. C., et al. (2009). Fate and transport of antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistance genes following land application of manure waste. J. Environ. Qual. 38 1086–1108. 10.2134/jeq2008.0128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clermont O., Bonacorsi S., Bingen E. (2000). Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 4555–4558. 10.1128/AEM.66.10.4555-4558.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collignon P. (2009). Resistant Escherichia coli–we are what we eat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49 202–204. 10.1086/599831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coque T. M., Novais A., Carattoli A., Poirel L., Pitout J., Peixe L., et al. (2008). Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 14 195–200. 10.3201/eid1402.070350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero O. X., Wildschutte H., Kirkup B., Proehl S., Ngo L., Hussain F., et al. (2012). Ecological populations of bacteria act as socially cohesive units of antibiotic production and resistance. Science 337 1228–1231. 10.1126/science.1219385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D., Poeta P., Saenz Y., Coelho A. C., Matos M., Vinue L., et al. (2008). Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance and resistance genes in faecal Escherichia coli isolates recovered from healthy pets. Vet. Microbiol. 127 97–105. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa D., Poeta P., Saenz Y., Vinue L., Rojo-Bezares B., Jouini A., et al. (2006). Detection of Escherichia coli harbouring extended-spectrum beta-lactamases of the CTX-M, TEM and SHV classes in faecal samples of wild animals in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 58 1311–1312. 10.1093/jac/dkl415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cully M. (2014). Public health: the politics of antibiotics. Nature 509 S16–S17. 10.1038/509S16a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport D. (2012). The war against bacteria: how were sulphonamide drugs used by Britain during World War II? Med. Humanit. 38 55–58. 10.1136/medhum-2011-010024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J., Davies D. (2010). Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74 417–433. 10.1128/MMBR.00016-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Costa V. M., Mcgrann K. M., Hughes D. W., Wright G. D. (2006). Sampling the antibiotic resistome. Science 311 374–377. 10.1126/science.1120800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leener E., Martel A., Decostere A., Haesebrouck F. (2004). Distribution of the erm (B) gene, tetracycline resistance genes, and Tn1545-like transposons in macrolide- and lincosamide-resistant enterococci from pigs and humans. Microb. Drug Resist. 10 341–345. 10.1089/mdr.2004.10.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ECDC (ed.) (2011). Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance in Europe. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC (ed.) (2013). Surveillance Report: Anual Epidemiological Report 2013. Stockholm: Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner H. (1910). The new treatment of syphilis (ehrlich-hata): observations and results. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 55 2052–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Enne V. I., Cassar C., Sprigings K., Woodward M. J., Bennett P. M. (2008). A high prevalence of antimicrobial resistant Escherichia coli isolated from pigs and a low prevalence of antimicrobial resistant E. coli from cattle and sheep in Great Britain at slaughter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278 193–199. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00991.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2013). Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial Agents in 25 EU/EEA Countries in 2011. Report EMA/236501/2013 London: European Medicines Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo N., Radhouani H., Goncalves A., Rodrigues J., Carvalho C., Igrejas G., et al. (2009). Genetic characterization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci isolates from wild rabbits. J. Basic Microbiol. 49 491–494. 10.1002/jobm.200800387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A. (2001). On the antibacterial action of cultures of a penicillium, with special reference to their use in the isolation of B. influenzae, 1929. Bull. World Health Organ. 79 780–790. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluit A. C., Schmitz F. J., Verhoef J., European S. P. G. (2001). Frequency of isolation of pathogens from bloodstream, nosocomial pneumonia, skin and soft tissue, and urinary tract infections occurring in European patients. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20 188–191. 10.1007/s10096-001-8078-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank T., Gautier V., Talarmin A., Bercion R., Arlet G. (2007). Characterization of sulphonamide resistance genes and class 1 integron gene cassettes in Enterobacteriaceae, Central African Republic (CAR). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59 742–745. 10.1093/jac/dkl538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz C. M., Huch M., Abriouel H., Holzapfel W., Galvez A. (2011). Enterococci as probiotics and their implications in food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 151 125–140. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French G. L. (2010). The continuing crisis in antibiotic resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36(Suppl. 3), S3–S7. 10.1016/S0924-8579(10)70003-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya E. Y., Lowy F. D. (2006). Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in the community setting. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4 36–45. 10.1038/nrmicro1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M. K., Forsberg K. J., Dantas G. (2015). Improved annotation of antibiotic resistance determinants reveals microbial resistomes cluster by ecology. ISME J. 9 207–216. 10.1038/ismej.2014.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillings M. R. (2013). Evolutionary consequences of antibiotic use for the resistome, mobilome and microbial pangenome. Front. Microbiol. 4:4 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillings M. R., Stokes H. W. (2012). Are humans increasing bacterial evolvability? Trends Ecol. Evol. 27 346–352. 10.1016/j.tree.2012.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh E. B., Yim G., Tsui W., Mcclure J., Surette M. G., Davies J. (2002). Transcriptional modulation of bacterial gene expression by subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 17025–17030. 10.1073/pnas.252607699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A., Igrejas G., Radhouani H., Correia S., Pacheco R., Santos T., et al. (2013a). Antimicrobial resistance in faecal enterococci and Escherichia coli isolates recovered from Iberian wolf. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 56 268–274. 10.1111/lam.12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A., Igrejas G., Radhouani H., Estepa V., Alcaide E., Zorrilla I., et al. (2012). Detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates in faecal samples of Iberian lynx. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 54 73–77. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A., Igrejas G., Radhouani H., Lopez M., Guerra A., Petrucci-Fonseca F., et al. (2011). Detection of vancomycin-resistant enterococci from faecal samples of Iberian wolf and Iberian lynx, including Enterococcus faecium strains of CC17 and the new singleton ST573. Sci. Total Environ. 41 266–268. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.09.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves A., Igrejas G., Radhouani H., Santos T., Monteiro R., Pacheco R., et al. (2013b). Detection of antibiotic resistant enterococci and Escherichia coli in free range Iberian Lynx (Lynx pardinus). Sci. Total Environ. 45 115–119. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.03.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GR & DS (ed.) (2012). Global Antibiotics Market to 2016. Lahti: GlobalResearch & Data Services. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann H., Aires-De-Sousa M., Boyce J., Tiemersma E. (2006). Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet 368 874–885. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68853-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra B., Junker E., Schroeter A., Malorny B., Lehmann S., Helmuth R. (2003). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in German Escherichia coli isolates from cattle, swine and poultry. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52 489–492. 10.1093/jac/dkg362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hede K. (2014). Antibiotic resistance: an infectious arms race. Nature 509 S2–S3. 10.1038/509S2a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joakim Larsson D. G. (2014). Pollution from drug manufacturing: review and perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 369:20130571 10.1098/rstb.2013.0571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M. E. (1999). Towards better surveillance of bacterial antibiotic resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5 61–63. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1999.tb00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Nataro J. P., Mobley H. L. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirst H. A., Thompson D. G., Nicas T. I. (1998). Historical yearly usage of vancomycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 1303–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn I., Iversen A., Burman L. G., Olsson-Liljequist B., Franklin A., Finn M., et al. (2003). Comparison of enterococcal populations in animals, humans, and the environment–a European study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 88 133–145. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00176-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapierre L., Cornejo J., Borie C., Toro C., San Martin B. (2008). Genetic characterization of antibiotic resistance genes linked to class 1 and class 2 integrons in commensal strains of Escherichia coli isolated from poultry and swine. Microb. Drug Resist. 14 265–272. 10.1089/mdr.2008.0810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. G. (2005). “The dynamic bacterial genome,” in The Bacterial Chromosome, ed. Higgins N. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Le-Minh N., Khan S. J., Drewes J. E., Stuetz R. M. (2010). Fate of antibiotics during municipal water recycling treatment processes. Water Res. 44 4295–4323. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B. (2001). Antibiotic resistance: consequences of inaction. Clin. Infect. Dis 33(Suppl. 3), S124–S129. 10.1086/321837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S. B., Marshall B. (2004). Antibacterial resistance worldwide: causes, challenges and responses. Nat. Med. 10 S122–S129. 10.1038/nm1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Yang M., Hu J., Zhang J., Liu R., Gu X., et al. (2009). Antibiotic-resistance profile in environmental bacteria isolated from penicillin production wastewater treatment plant and the receiving river. Environ. Microbiol. 11 1506–1517. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01878.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Pop M. (2009). ARDB–antibiotic resistance genes database. Nucleic Acids Res. 37 D443–D447. 10.1093/nar/gkn656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho C., Silva N., Pombo S., Santos T., Monteiro R., Goncalves A., et al. (2013). Echinoderms from Azores islands: an unexpected source of antibiotic resistant Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli isolates. Mar. pollut. Bull. 69 122–127. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. L., Baquero F., Andersson D. I. (2007). Predicting antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5 958–965. 10.1038/nrmicro1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur A. G., Waglechner N., Nizam F., Yan A., Azad M. A., Baylay A. J., et al. (2013). The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 3348–3357. 10.1128/AAC.00419-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moura I., Radhouani H., Torres C., Poeta P., Igrejas G. (2010). Detection and genetic characterisation of vanA-containing Enterococcus strains in healthy Lusitano horses. Equine Vet. J. 42 181–183. 10.2746/042516409X480386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterblad M., Norrdahl K., Korpimaki E., Huovinen P. (2001). Antibiotic resistance. How wild are wild mammals? Nature 409 37–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallecchi L., Bartoloni A., Paradisi F., Rossolini G. M. (2008). Antibiotic resistance in the absence of antimicrobial use: mechanisms and implications. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6 725–732. 10.1586/14787210.6.5.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappaioanou M., Spencer H. (2008). “One Health” initiative and ASPH. Public Health Rep. 123:261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini C., Celenza G., Segatore B., Bellio P., Setacci D., Amicosante G., et al. (2011). Occurrence of class 1 and 2 integrons in resistant Enterobacteriaceae collected from a urban wastewater treatment plant: first report from central Italy. Microb. Drug Resist. 17 229–234. 10.1089/mdr.2010.0117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira H. M., Domingos T., Vicente L. (eds) (2004). Portugal Millennium Ecosystem Assessment: State of the Assessment Report. Lisbon: Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa. [Google Scholar]

- Perreten V., Boerlin P. (2003). A new sulfonamide resistance gene (sul3) in Escherichia coli is widespread in the pig population of Switzerland. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47 1169–1172. 10.1128/AAC.47.3.1169-1172.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Costa D., Igrejas G., Rodrigues J., Torres C. (2007a). Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in faecal enterococci from wild boars (Sus scrofa). Vet. Microbiol. 125 368–374. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Costa D., Igrejas G., Rojo-Bezares B., Saenz Y., Zarazaga M., et al. (2007b). Characterization of vanA-containing Enterococcus faecium isolates carrying Tn5397-like and Tn916/Tn1545-like transposons in wild boars (Sus Scrofa). Microb. Drug Resist. 13 151–156. 10.1089/mdr.2007.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Costa D., Rodrigues J., Torres C. (2005a). Study of faecal colonization by vanA-containing Enterococcus strains in healthy humans, pets, poultry and wild animals in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 55 278–280. 10.1093/jac/dkh549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Costa D., Saenz Y., Klibi N., Ruiz-Larrea F., Rodrigues J., et al. (2005b). Characterization of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors in faecal enterococci of wild animals in Portugal. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 52 396–402. 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2005.00881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Igrejas G., Goncalves A., Martins E., Araujo C., Carvalho C., et al. (2009). Influence of oral hygiene in patients with fixed appliances in the oral carriage of antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli and Enterococcus isolates. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 108 557–564. 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poeta P., Radhouani H., Goncalves A., Figueiredo N., Carvalho C., Rodrigues J., et al. (2010). Genetic characterization of antibiotic resistance in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli carrying extended-spectrum beta-lactamases recovered from diarrhoeic rabbits. Zoonoses Public Health 57 162–170. 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2008.01221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Igrejas G., Goncalves A., Pacheco R., Monteiro R., Sargo R., et al. (2013). Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes in Escherichia coli and enterococci from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Anaerobe 23 82–86. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Igrejas G., Pinto L., Goncalves A., Coelho C., Rodrigues J., et al. (2011). Molecular characterization of antibiotic resistance in enterococci recovered from seagulls (Larus cachinnans) representing an environmental health problem. J. Environ. Monit. 13 2227–2233. 10.1039/c0em00682c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Pinto L., Coelho C., Sargo R., Araujo C., Lopez M., et al. (2010). MLST and a genetic study of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in vanA-containing Enterococcus from buzzards (Buteo buteo). Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 50 537–541. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02807.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Poeta P., Goncalves A., Pacheco R., Sargo R., Igrejas G. (2012). Wild birds as biological indicators of environmental pollution: antimicrobial resistance patterns of Escherichia coli and enterococci isolated from common buzzards (Buteo buteo). J. Med. Microbiol. 61 837–843. 10.1099/jmm.0.038364-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Poeta P., Igrejas G., Goncalves A., Vinue L., Torres C. (2009). Antimicrobial resistance and phylogenetic groups in isolates of Escherichia coli from seagulls at the Berlengas nature reserve. Vet. Rec. 165 138–142. 10.1136/vr.165.5.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhouani H., Silva N., Poeta P., Torres C., Correia S., Igrejas G. (2014). Potential impact of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife, environment and human health. Front. Microbiol. 5:23 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radimersky T., Frolkova P., Janoszowska D., Dolejska M., Svec P., Roubalova E., et al. (2010). Antibiotic resistance in faecal bacteria (Escherichia coli. Enterococcus spp.) in feral pigeons. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109 1687–1695. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos S., Igrejas G., Rodrigues J., Capelo-Martinez J. L., Poeta P. (2012). Genetic characterisation of antibiotic resistance and virulence factors in vanA-containing enterococci from cattle, sheep and pigs subsequent to the discontinuation of the use of avoparcin. Vet. J. 193 301–303. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues J., Poeta P., Martins A., Costa D. (2001). The importance of pets as reservoirs of resistant Enterococcus strains, with special reference to vancomycin. J. Vet. Med. 49 278–280. 10.1046/j.1439-0450.2002.00561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossolini G. M., Thaller M. C. (2010). Coping with antibiotic resistance: contributions from genomics. Genome Med. 2:15 10.1186/gm136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz Y., Brinas L., Dominguez E., Ruiz J., Zarazaga M., Vila J., et al. (2004). Mechanisms of resistance in multiple-antibiotic-resistant Escherichia coli strains of human, animal, and food origins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48 3996–4001. 10.1128/AAC.48.10.3996-4001.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos T., Silva N., Igrejas G., Rodrigues P., Micael J., Rodrigues T., et al. (2013). Dissemination of antibiotic resistant Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli from wild birds of Azores Archipelago. Anaerobe 24 25–31. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2013.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah A. K., Meyer M. T., Boxall A. B. (2006). A global perspective on the use, sales, exposure pathways, occurrence, fate and effects of veterinary antibiotics (VAs) in the environment. Chemosphere 65 725–759. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayah R. S., Kaneene J. B., Johnson Y., Miller R. (2005). Patterns of antimicrobial resistance observed in Escherichia coli isolates obtained from domestic- and wild-animal fecal samples, human septage, and surface water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 1394–1404. 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1394-1404.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta S., Chattopadhyay M. K., Grossart H. P. (2013). The multifaceted roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front. Microbiol. 4:47 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva N., Igrejas G., Figueiredo N., Goncalves A., Radhouani H., Rodrigues J., et al. (2010). Molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance in enterococci and Escherichia coli isolates from European wild rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Sci. Total Environ. 408 4871–4876. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skold O. (2010). Sulfonamides and trimethoprim. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 8 1–6. 10.1586/eri.09.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skurnik D., Ruimy R., Andremont A., Amorin C., Rouquet P., Picard B., et al. (2006). Effect of human vicinity on antimicrobial resistance and integrons in animal faecal Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57 1215–1219. 10.1093/jac/dkl122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellberg B., Powers J. H., Brass E. P., Miller L. G., Edwards J. E., Jr. (2004). Trends in antimicrobial drug development: implications for the future. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38 1279–1286. 10.1086/420937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenover F. C. (2006). Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria. Am. J. Infect. Control 34 S3–S10. 10.1016/j.ajic.2006.05.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuber M. (1999). Spread of antibiotic resistance with food-borne pathogens. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 56 755–763. 10.1007/s000180050022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuber M., Perreten V. (2000). Role of milk and meat products as vehicles for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Acta Vet. Scand. Suppl. 93 75–87;discussion 111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uttley A. H., Collins C. H., Naidoo J., George R. C. (1988). Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet 1 57–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)91037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Boeckel T. P., Gandra S., Ashok A., Caudron Q., Grenfell B. T., Levin S. A., et al. (2014). Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14 742–750. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaard A. E., Stobberingh E. E. (2000). Epidemiology of resistance to antibiotics. Links between animals and humans. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 14 327–335. 10.1016/S0924-8579(00)00145-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijn P. J., Dautzenberg M. J., Oostdijk E. A. (2011). Recent trends in antibiotic resistance in European ICUs. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 17 658–665. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c9d87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schaik W. (2015). The human gut resistome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370 20140087 10.1098/rstb.2014.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. (2013). The multiple roles of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Front. Microbiol. 4:255 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener H. (2012). “Antibiotic resistance - linking human and animal health,” in Improving Food Safety Through a One Health Approach: Workshop Summary, ed. Institute of Medicine (Washington, DC: National Acedemies Press; ). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener H. C. (1998). Historical yearly usage of glycopeptides for animals and humans: the American-European paradox revisited. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (ed.) (2014). Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report in Surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse M., Ward M., Van Bunnik B., Farrar J. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370 20140083 10.1098/rstb.2014.0083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi C., Zhang Y., Marrs C. F., Ye W., Simon C., Foxman B., et al. (2009). Prevalence of antibiotic resistance in drinking water treatment and distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 5714–5718. 10.1128/AEM.00382-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim G., Wang H. H., Davies J. (2007). Antibiotics as signalling molecules. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362 1195–1200. 10.1098/rstb.2007.2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuccato E., Calamari D., Natangelo M., Fanelli R. (2000). Presence of therapeutic drugs in the environment. Lancet 355 1789–1790. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02270-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]