Significance

This study provides evidence of a physical interaction between neurofibromin, an Ras-GTPase activating protein, and a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), the serotonin 5 hydroxytryptamine 6 (5-HT6) receptor. It also shows that constitutive activity of a GPCR depends on its association with GPCR-interacting proteins. Finally, it suggests that the 5-HT6 receptor may be considered as a potentially relevant therapeutic target to correct some neurofibromatosis type 1-related cognitive deficits, a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the gene encoding neurofibromin.

Keywords: 5-HT6 receptor, constitutive activity, G protein-coupled receptor, neurofibromin, neurofibromatosis type 1

Abstract

Active G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) conformations not only are promoted by agonists but also occur in their absence, leading to constitutive activity. Association of GPCRs with intracellular protein partners might be one of the mechanisms underlying GPCR constitutive activity. Here, we show that serotonin 5 hydroxytryptamine 6 (5-HT6) receptor constitutively activates the Gs/adenylyl cyclase pathway in various cell types, including neurons. Constitutive activity is strongly reduced by silencing expression of the Ras-GTPase activating protein (Ras-GAP) neurofibromin, a 5-HT6 receptor partner. Neurofibromin is a multidomain protein encoded by the NF1 gene, the mutation of which causes Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), a genetic disorder characterized by multiple benign and malignant nervous system tumors and cognitive deficits. Disrupting association of 5-HT6 receptor with neurofibromin Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain also inhibits receptor constitutive activity, and PH domain expression rescues 5-HT6 receptor-operated cAMP signaling in neurofibromin-deficient cells. Furthermore, PH domains carrying mutations identified in NF1 patients that prevent interaction with the 5-HT6 receptor fail to rescue receptor constitutive activity in neurofibromin-depleted cells. Further supporting a role of neurofibromin in agonist-independent Gs signaling elicited by native receptors, the phosphorylation of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) is strongly decreased in prefrontal cortex of Nf1+/− mice compared with WT mice. Moreover, systemic administration of a 5-HT6 receptor inverse agonist reduces CREB phosphorylation in prefrontal cortex of WT mice but not Nf1+/− mice. Collectively, these findings suggest that disrupting 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction prevents agonist-independent 5-HT6 receptor-operated cAMP signaling in prefrontal cortex, an effect that might underlie neuronal abnormalities in NF1 patients.

Among 14 serotonin [5 hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] receptor subtypes, the 5-HT6 receptor has emerged as a promising target for the treatment of cognitive impairment associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia: 5-HT6 receptor antagonists consistently enhance mnemonic performance in a broad range of procedures in rodents, and there is preliminary evidence for procognitive properties of 5-HT6 receptor antagonists and/or inverse agonists in humans (1–3).

The 5-HT6 receptor is a Gs-coupled receptor that activates cAMP formation on agonist stimulation in several recombinant systems (4–6) as well as in native systems, such as primary neurons (7) and pig caudate membranes (8). In addition to its coupling to G proteins, the 5-HT6 receptor interacts with the Src family tyrosine kinase Fyn (9), the Jun activation domain-binding protein 1 (10), and the microtubule-associated protein Map1b (11). The 5-HT6 receptor also recruits the mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Complex 1, and receptor-operated activation of mTOR signaling in prefrontal cortex (PFC) mediates its deleterious influence on cognition (12). Furthermore, 5-HT6 receptors associate with and activate Cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) in an agonist-independent manner through mechanisms involving receptor phosphorylation by associated Cdk5 to promote migration of neurons and neurite growth (13, 14).

Constitutive activity of 5-HT6 receptor was also established at Gs signaling in recombinant cells overexpressing WT or mutant receptors (5, 6), but the underlying mechanism remains to be established. In light of recent evidence indicating that G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) constitutive activity can be modulated by G protein-coupled receptor-interacting proteins (GIPs) (15), we focused on neurofibromin, another 5-HT6 receptor partner known to be involved in adenylyl cyclase activation by various GPCRs (12, 16). Neurofibromin is an Ras GTPase-activating protein (Ras-GAP) encoded by the tumor suppressor gene NF1. Mutations of the NF1 gene cause Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), one of the most common autosomal dominant diseases characterized by skin pigmentation (cafe au lait spots and freckling), multiple benign and malignant nervous system tumors, and learning and attention deficits (17). Learning deficits are observed in Nf1 heterozygous mice (Nf1+/−) (17, 18) and Nf1 null Drosophila melanogaster (19). Notably, learning impairments in Nf1 null flies are rescued by expression of a constitutively active form of PKA, suggesting that they are caused by decreased activation of adenylyl cyclase (19). Whether 5-HT6 receptors contribute to neurofibromin-dependent cAMP production remains to be explored. Likewise, the role of neurofibromin association with 5-HT6 receptor in receptor constitutive activity remains to be established.

Here, we show that constitutive activity of 5-HT6 receptor at Gs signaling is critically dependent on a physical interaction between the receptor C-terminal domain (CTD) and the neurofibromin Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain. Moreover, mutations located in the PH domain identified in NF1 patients, which disrupt the association of 5-HT6 receptor with neurofibromin, strongly inhibit agonist-independent receptor-operated Gs signaling that is also impaired in a mouse model of NF1. This study identifies the 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction as a molecular substrate that might contribute to neuronal abnormalities and cognitive impairment observed in NF1 patients.

Results

5-HT6 Receptor Recruits Neurofibromin via Its PH Domain and CTD.

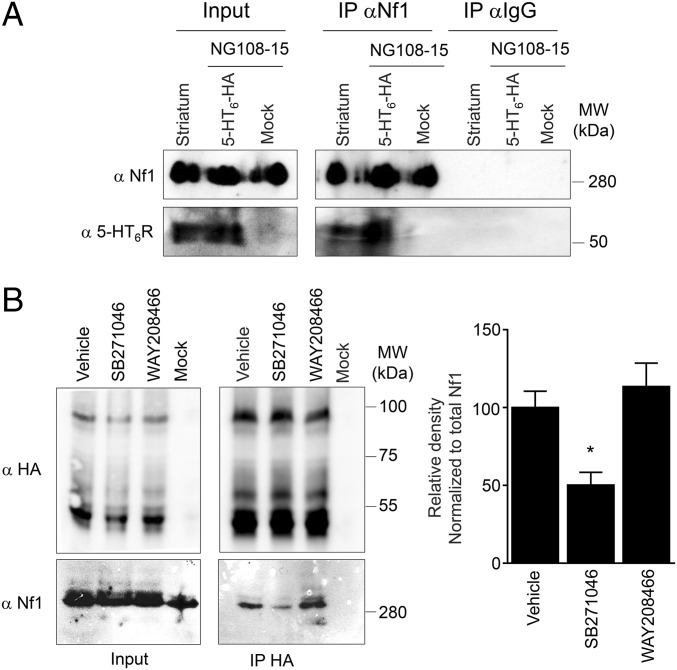

Our previous studies of the 5-HT6 receptor interactome identified neurofibromin as a candidate receptor partner (12). Immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis confirmed the interaction of endogenously expressed neurofibromin with human (HA)-tagged 5-HT6 receptor expressed in neuroblastoma–glioma NG108-15 cells (Fig. 1A). Native 5-HT6 receptor also coimmunoprecipitated with neurofibromin in protein extracts from mice striatum, the brain region expressing the highest receptor density (Fig. 1A). Because no 5-HT6 receptor antibody that efficiently immunoprecipitates the mouse receptor was available, we immunoprecipitated 5-HT6 receptors from knock-in mice expressing a GFP-tagged version of the receptor (5-HT6-GFP) using a GFP nanobody and found that neurofibromin coimmunoprecipitates with 5-HT6-GFP receptor (Fig. S1A). Furthermore, 5-HT6-GFP receptors and neurofibromin are colocalized at the surface of cell bodies of neurons from various brain regions, including the striatum and the CA3 area of the hippocampus (Fig. S1B). Collectively, these findings indicate that native 5-HT6 receptors form complexes with neurofibromin in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Association of 5-HT6 receptor with neurofibromin PH domain is dependent on receptor conformational state. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of neurofibromin with native 5-HT6 receptor from mouse striatum and human HA-tagged 5-HT6 receptor expressed in NG108-15. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation of neurofibromin with HA-5-HT6 receptor expressed in NG108-15 cells treated with vehicle, WAY208466, or SB271046 for 30 min. The histogram represents the results of densitometric analyses of three independent experiments. Data are means ± SEM. Inputs represent 5% of the total protein amount used for immunoprecipitations (IPs). Representative blots of three independent experiments are illustrated. MW, molecular mass. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

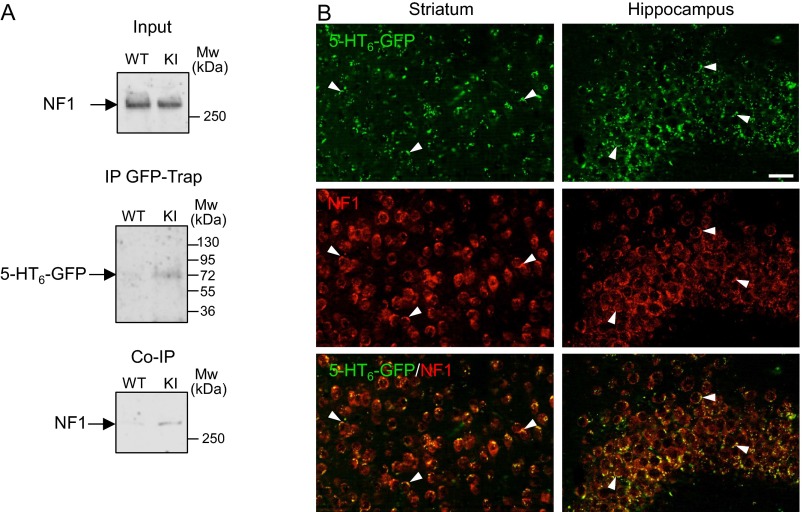

Fig. S1.

5-HT6 receptor and neurofibromin form a complex in the brain of 5-HT6-GFP knock-in (KI) mice. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) of neurofibromin with 5-HT6 receptor from 5-HT6-GFP knock-in mouse brain. Control immunoprecipitation (IP) was performed from WT mouse brain protein extract. Representative results of three independent experiments performed with different mice are illustrated. Mw, molecular mass. (B) Immunofluorescent detection of 5-HT6-GFP receptor and neurofibromin in the striatum and the CA3 area of hippocampus of 5-HT6-GFP knock-in mice. One-micrometer slice images were acquired with a 20× objective using the Apotome mode. Representative fields from 10 sections originating from four mice are illustrated. Arrowheads indicate colocalization of 5-HT6-GFP receptor and neurofibromin at the cell surface of cell bodies of neurons in both brain regions. (Scale bar: 50 μm.)

Coimmunoprecipitation studies and bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) experiments showed that both PH domain and CTD of neurofibromin interact with the 5-HT6 receptor (SI Materials and Methods, SI Results, and Figs. S2 and S3A). Further supporting a specific interaction between neurofibromin and 5-HT6 receptor, no interaction was detected between PH domain and 5-HT4 or 5-HT7 receptor, two other Gs-coupled 5-HT receptors (SI Materials and Methods, SI Results, and Fig. S3B).

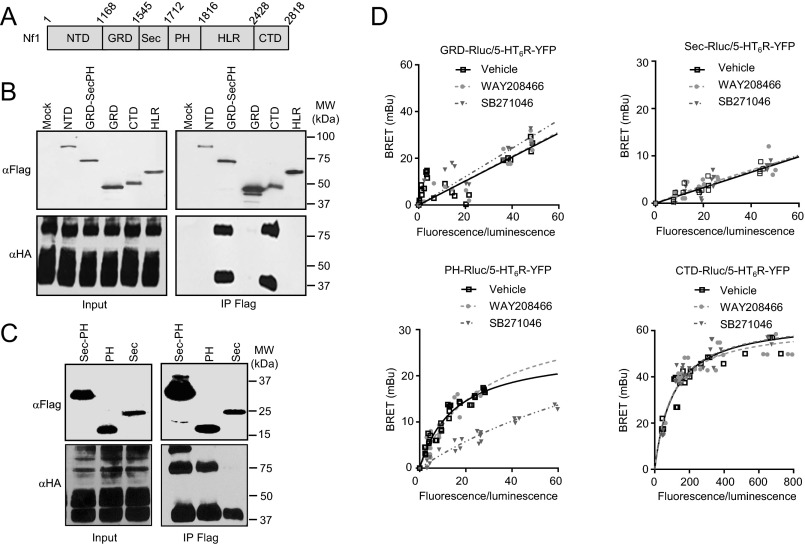

Fig. S2.

(A) Schematic representation of neurofibromin and its different domains analyzed for their ability to interact with 5-HT6 receptor: NTD, GRD, Sec, PH, and HLR. (B and C) Coimmunoprecipitations of HA-tagged 5-HT6 receptor with Flag-tagged neurofibromin domains expressed in HEK-293T cells as indicated. IP, immunoprecipitation; MW, molecular mass. (D) BRET analysis of the interaction between neurofibromin domains and 5-HT6 receptor. BRET titration curves were generated in HEK-293 cells expressing a constant amount of transfected RLuc-tagged constructs containing GRD, Sec domain, PH domain, or CTD (25 ng, donor) and increasing amounts of 5-HT6-YFP receptor (from 0 to 2 µg, acceptor) and exposed to vehicle, WAY208466 (1 µM), or SB271046 (1 µM) for 20 min. Plotted results are from three independent experiments.

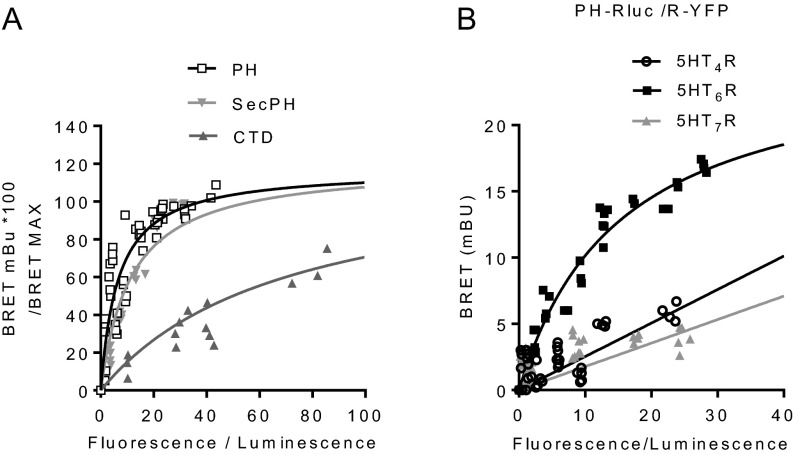

Fig. S3.

PH domain strongly and specifically interacts with 5-HT6 receptor. (A) PH and SecPH domains interact with 5-HT6 receptor with higher relative affinity compared with CTD. HEK-293 cells were transfected with a constant amount of 5-HT6-RLuc construct and increasing amounts of YFP-tagged constructs encoding neurofibromin domains (CTD, SecPH, or PH). BRET values were expressed as percentage of the maximal BRET reached (BRETmax) and plotted as a function of the fluorescence/luminescence ratio. Plotted results are from three independent experiments. BRET50 values obtained with SecPH and PH domains (BRET50 = 11.5 ± 3.2 and 6.6 ± 1.4, respectively) were significantly lower (P < 0.01) compared with that obtained with CTD (BRET50 = 92.1 ± 27.9). (B) Neurofibromin PH domain does not interact with serotonin 5-HT4 and 5-HT7 receptors. HEK-293 cells were transfected with a constant amount (25 ng) of PH-RLuc plasmid and increasing amounts of 5-HT4-YFP, 5-HT6-YFP, or 5-HT7-YFP constructs. Contrasting what was observed in 5-HT6 receptor-expressing cells, BRET signals increased linearly in cells expressing 5-HT4 or 5-HT7 receptor, indicating nonspecific and random interactions.

Association of YFP-tagged 5-HT6 receptor (5-HT6-YFP) with PH-Rluc and CTD-Rluc, already detected in absence of receptor ligand, was not further enhanced by exposure of cells to WAY208466, a specific 5-HT6 receptor agonist (Fig. S2D). Treatment of cells with SB271046, a 5-HT6 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist, induced a strong decrease in BRET signal between 5-HT6-YFP and PH-Rluc, whereas it did not affect association of 5-HT6-YFP with CTD-Rluc (Fig. S2D). Likewise, coimmunoprecipitation of neurofibromin with 5-HT6 receptor was not significantly enhanced by treating cells with WAY208466, whereas SB271046 strongly reduced the coimmunoprecipitation of neurofibromin with 5-HT6 receptor (Fig. 1B), suggesting a predominant contribution of PH domain vs. CTD in the association of both proteins. We, thus, focused on this interaction in additional experiments.

Neurofibromin Interacts with the CTD of 5-HT6 Receptor.

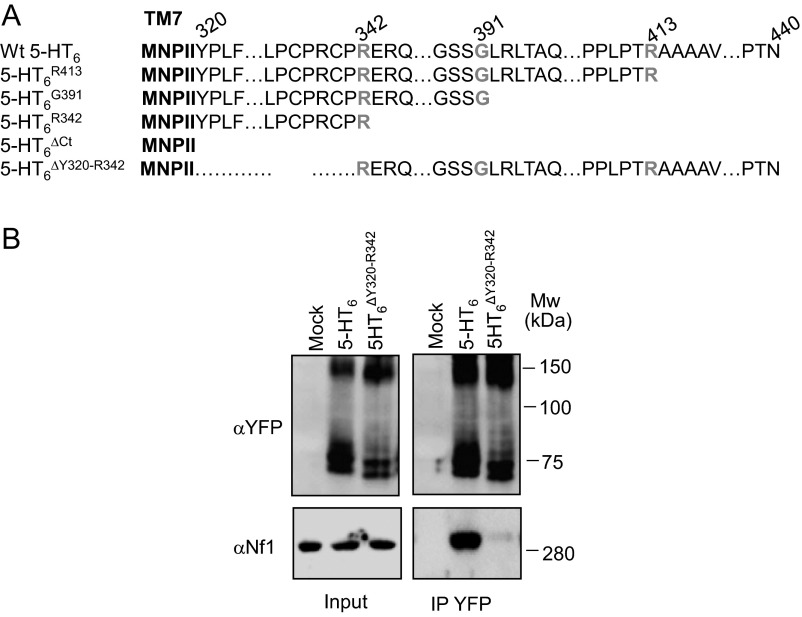

Previous studies have identified the CTD of GPCRs as a key domain involved in the recruitment of GIPs (20). Using several truncation mutants (deleted of C-terminal residues) of the receptor (Fig. S4A), we showed an essential role of 22 N-terminal residues of the receptor CTD in 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction (Fig. 2 A and B, SI Materials and Methods, SI Results, and Fig. S4B). We then generated a cell-permeable interfering peptide composed of the transduction domain of the HIV TAT protein fused to these residues (TAT Ct22 peptide) to block 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction. Treatment of cells with the TAT Ct22 peptide but not with a scrambled peptide abolished the specific BRET saturation signal observed in cells coexpressing 5-HT6-YFP and PH-RLuc (Fig. 2C). Collectively, these results show the importance of the 22 N-terminal residues of 5-HT6 receptor CTD in mediating the interaction with the PH domain of neurofibromin.

Fig. S4.

5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction depends on the presence of 22 N-terminal amino acids of 5-HT6 receptor CTD. (A) Amino acid sequences of WT and truncated mutants of 5-HT6 receptor CTD generated to identify neurofibromin binding motif. (B) HEK-293 cells were transfected with 5-HT6-YFP receptor constructs as indicated. Cell lysates were harvested 48 h after transfection. WT and mutated 5-HT6 receptors were immunoprecipitated using the GFP-Trap Kit. Inputs represent 5% of the total protein amount used for immunoprecipitation (IP). Receptor and neurofibromin were detected using the GFP and neurofibromin antibodies, respectively. Representative gels of three independent experiments performed on different cultures are illustrated. MW, molecular mass.

Fig. 2.

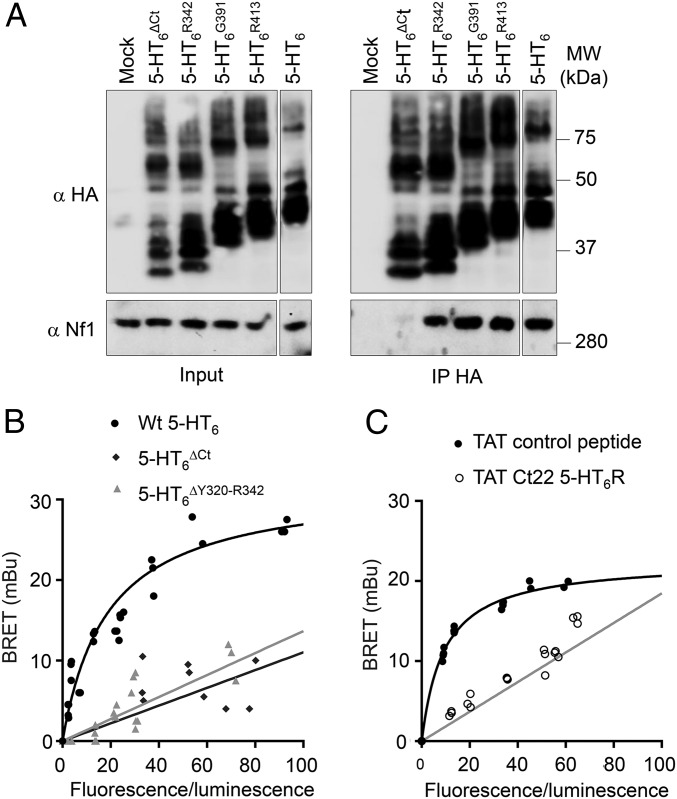

The juxtamembrane segment of 5-HT6 receptor CTD interacts with neurofibromin PH domain. (A) The corresponding constructs encoding HA-tagged 5-HT6 receptor were transfected in HEK-293 cells as indicated, and receptors were immunoprecipitated using anti-HA antibody-conjugated beads. Representative immunoblots of three independent experiments are illustrated. The different gel lanes for each panel originate from a unique original Western blot. Inputs represent 5% of the total protein amount used for immunoprecipitation (IP). (B) BRET titration curves were generated in HEK-293 cells expressing a constant amount of PH-RLuc (donor) and increasing amounts of 5-HT6-YFP (acceptor) as indicated. Plotted results are from three independent experiments. (C) Cells transfected with 5-HT6-Luc construct and increasing concentrations of PH-YFP construct were treated for 2 h with TAT control or TAT Ct22 peptide (10 µM) before BRET measurement. Plotted results are from three independent experiments. MW, molecular mass.

Neurofibromin Depletion Inhibits 5-HT6 Receptor Constitutive Activity at Gs Signaling.

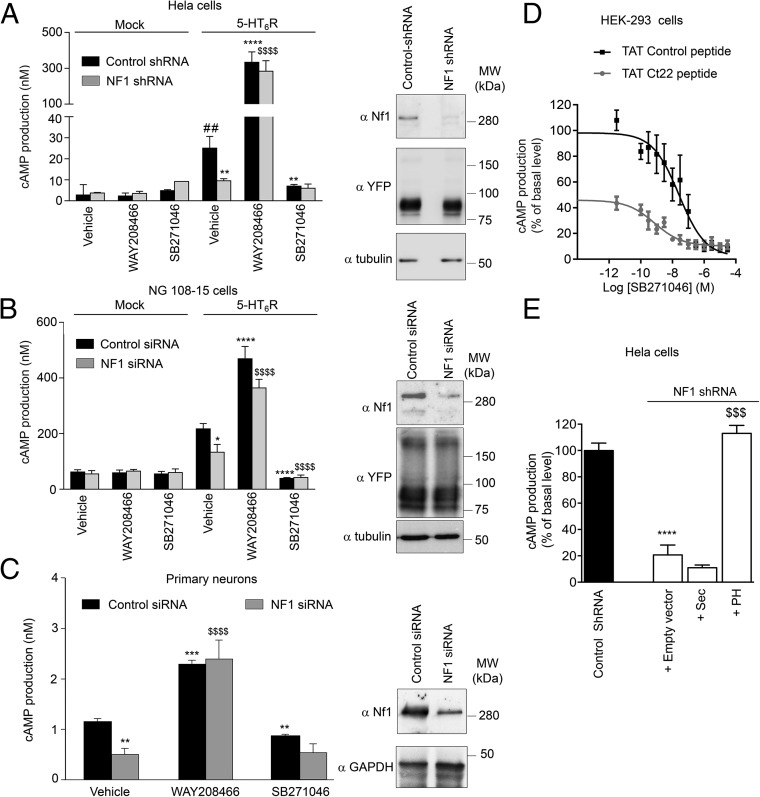

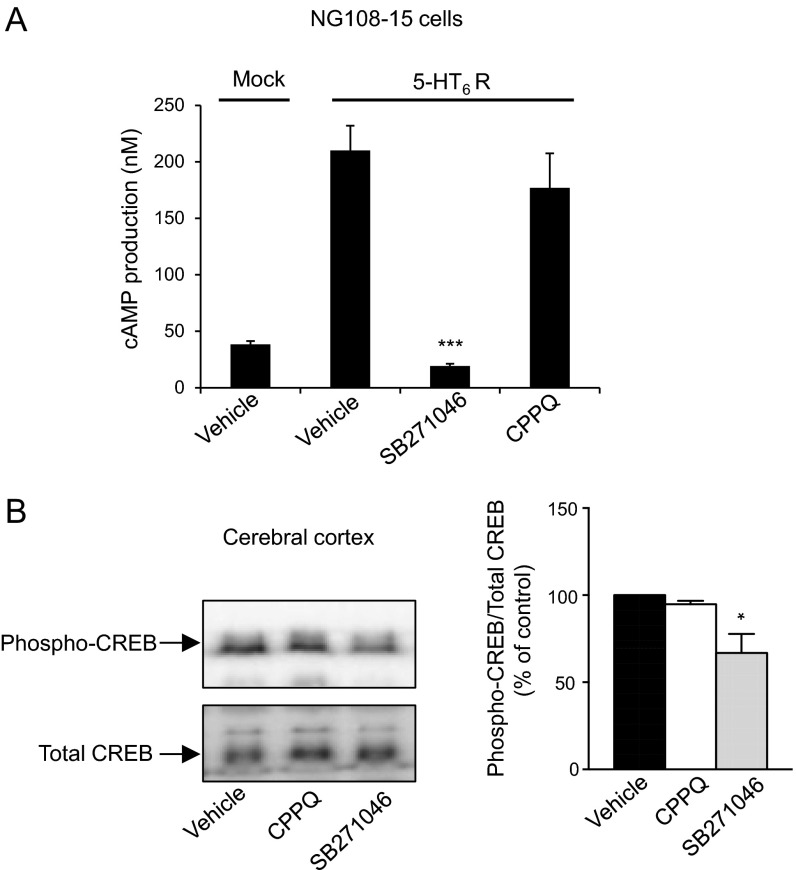

Stable silencing of neurofibromin expression using an shRNA strongly inhibited constitutive activation of cAMP production in HeLa cells induced by expression of the human 5-HT6 receptor (Fig. 3A and Fig. S5A). The amplitude of this inhibition represented about 80% of the reduction of constitutive activity induced by treating cells expressing control shRNA with a maximally effective concentration of SB271046 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S5A). This effect did not result from a decrease in 5-HT6 receptor expression in neurofibromin-depleted cells as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A, Right) and ELISA assessing 5-HT6 receptor plasma membrane expression (o.d. arbitrary unit = 1.60 ± 0.05 and 1.35 ± 0.20, P > 0.05 in HeLa cells expressing control shRNA and neurofibromin shRNA, respectively). In contrast, depleting cells of neurofibromin did not significantly affect cAMP production induced by WAY208466 (Fig. 3A). Neurofibromin depletion in cells expressing 5-HT4 receptor, another Gs-coupled 5-HT receptor that displays strong constitutive activity (21) but does not interact with neurofibromin PH domain, did not alter basal cAMP level or the amplitude of the inhibitory effect of Ro1162617, a 5-HT4 receptor inverse agonist (Fig. S5B). This finding suggests that neurofibromin specifically modulates 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity.

Fig. 3.

Neurofibromin promotes 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity at Gs/cAMP signaling. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing neurofibromin shRNA or control shRNA were transfected with the plasmid encoding human HA-5-HT6 receptor and stimulated with vehicle, WAY208466, or SB271046 (1 μM). cAMP production was quantified by time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET). (B) NG108-15 cells, transiently transfected with control or neurofibromin siRNA and either empty vector (Mock) or plasmid encoding 5-HT6-YFP, were treated as in A. (C) Primary striatal neurons were transfected with control or neurofibromin siRNA and treated as in A. In A–C, data illustrated in histograms are means ± SEM of values obtained in four independent experiments, and A, Right, B, Right, and C, Right show efficient silencing of neurofibromin expression by shRNA/siRNA. MW, molecular mass. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle in cells expressing control siRNA and 5-HT6 receptor or vehicle in neurons expressing control siRNA; **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle in cells expressing control siRNA and 5-HT6 receptor or vehicle in neurons expressing control siRNA; ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle in cells expressing control siRNA and 5-HT6 receptor or vehicle in neurons expressing control siRNA; ****P < 0.0001 vs. vehicle in cells expressing control siRNA and 5-HT6 receptor or vehicle in neurons expressing control siRNA; ##P < 0.01 vs. vehicle in mock cells; $$$$P < 0.0001 vs. vehicle in cells transfected with neurofibromin siRNA and expressing 5-HT6 receptor. (D) HEK-293 cells expressing WT receptors were treated with TAT control or Ct22 peptide (10 µM) for 2 h before SB271046 application. (E) HeLa cells stably expressing neurofibromin shRNA were cotransfected with 5-HT6 receptor construct and plasmids encoding Flag-tagged Sec or PH domains of neurofibromin. Data in D and E are means ± SEM of values obtained in three independent experiments. ****P < 0.0001 vs. control shRNA; $$$P < 0.001 vs. empty vector in cells expressing neurofibromin shRNA.

Fig. S5.

Neurofibromin specifically enhances 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity. HeLa cells stably expressing neurofibromin shRNA or control shRNA were transfected with constructs encoding HA-tagged 5-HT6 (A) or 5-HT4 receptors (B); 48 h after transfection, cells were stimulated for 1 h with incremental concentrations of 5-HT6 or 5-HT4 receptor inverse agonists (SB271046 or ro116 2617, respectively). cAMP production was quantified by time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET). Data are means ± SEM of values obtained in a typical experiment performed in triplicate. Two other independent experiments performed on different cultures yielded similar results.

Silencing neurofibromin expression in both a neuronal cell line (NG108-15) and primary striatal neurons resulted in decreased basal cAMP levels, whereas it did not affect agonist-induced cAMP accumulation (Fig. 3 B, Left and C, Left). Notably, in mouse striatal neurons depleted of neurofibromin, basal cAMP level was similar to that measured in control siRNA-transfected neurons treated with SB271046. Moreover, the inverse agonist did not further decrease cAMP level, indicating a complete loss of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity in neurofibromin-depleted neurons (Fig. 3C).

Disruption of the 5-HT6 Receptor–Neurofibromin Interaction Inhibits Receptor Constitutive Activity.

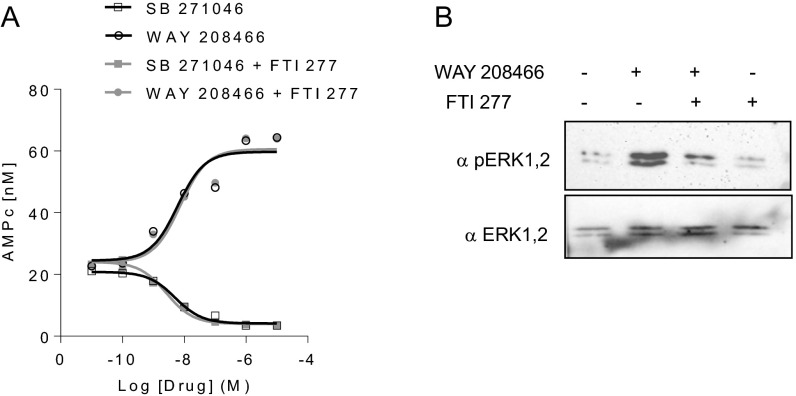

Pretreatment of HEK-293 cells expressing 5-HT6 receptor with the TAT Ct22 peptide, which disrupts receptor–neurofibromin interaction (Fig. 2C), strongly reduced the basal cAMP level (otherwise inhibited by incremental concentrations of SB271046) compared with that measured in cells treated with the TAT control peptide (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, expression of the PH domain but not the region homologous to the yeast Sec14p protein (Sec) domain in neurofibromin-depleted HeLa cells fully restored the level of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity measured in presence of neurofibromin (Fig. 3E), indicating that the receptor’s constitutive activity at Gs signaling is critically dependent on the physical interaction between 5-HT6 receptor CTD (residues 320–342) and neurofibromin PH domain. Neither basal nor agonist-stimulated cAMP production were altered in cells treated with FTI277, a specific Ras inhibitor, ruling out a role of Ras GTPase activity of neurofibromin in its control of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity (Fig. S6).

Fig. S6.

GTPase activity of neurofibromin is not involved in enhancement of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity. (A) HEK-293 cells transiently expressing 5-HT6 receptor were pretreated or not with the Ras inhibitor FTI277 (10 µM) and exposed to incremental concentrations of WAY208466 or SB271046 for 10 min. cAMP accumulation was measured using a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET) assay. (B) The ability of FTI277 to inhibit Ras was validated by measuring its impact on receptor-elicited activation of ERK signaling pathway as assessed by sequential immunoblotting with anti-pERK anti-ERK antibodies. A Western blot representative of three independent experiments performed on different sets of cultured cells is illustrated.

Impact of Nf1 Mutations on 5-HT6 Receptor Constitutive Activity.

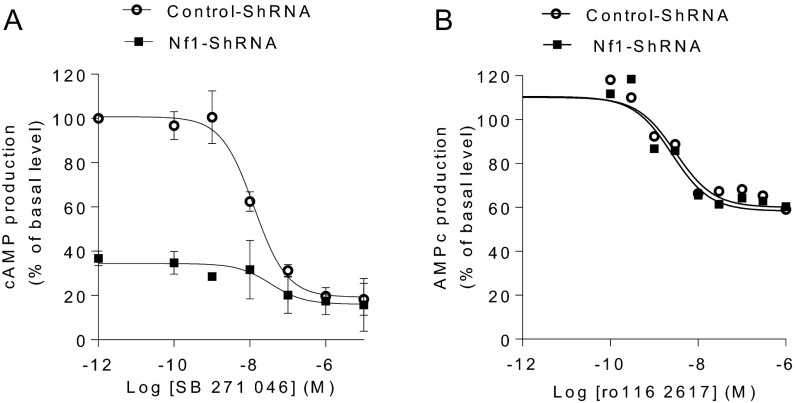

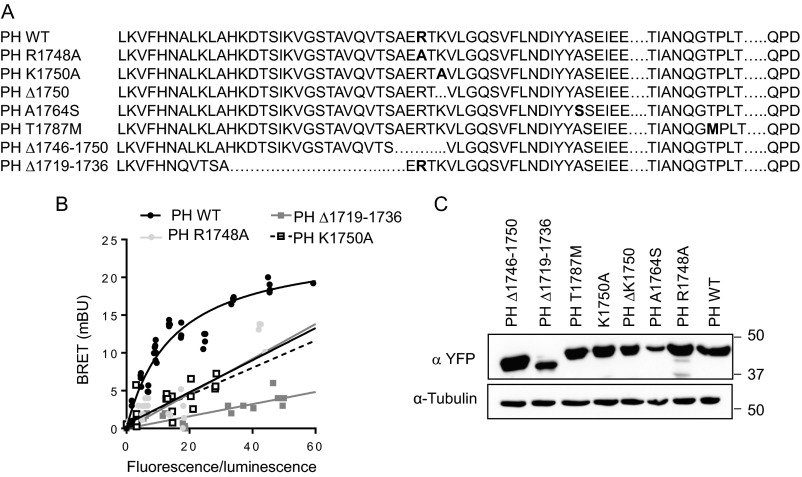

Mutations located in neurofibromin PH domain identified in NF1 patients (Fig. S7A) differentially affect its interaction with 5-HT6 receptor. The A1764S and T1787M PH domain mutants produced comparable BRET signals to those obtained with WT PH domain (Fig. 4A). In contrast, no specific BRET signal was detected in cells expressing R1748A, K1750A, Δ1719–1736, Δ1746–1750, or ΔK1750 mutant (Fig. 4A and Fig. S7B; Fig. S7C also shows expression of WT and mutant PH domains in HEK-293 cells). Corroborating their differential capabilities to interact with 5-HT6 receptor, expression of A1764S and T1787M mutants rescued the deficit in receptor constitutive activity induced by neurofibromin depletion and thus, reproduced the effect of reexpression of WT PH domain, whereas the Δ1746–1750 and ΔK1750 mutants did not restore cAMP levels resulting from agonist-independent receptor activation (Fig. 4B).

Fig. S7.

Neurofibromin PH domain mutants identified in NF1 patients: impact on association with 5-HT6 receptor. (A) Mutations or deletions in neurofibromin PH domain identified in NF1 patients. (B) HEK-293 cells were transfected with a constant amount of 5-HT6-RLuc construct and increasing concentrations of YFP-tagged PH domain constructs as indicated. BRET signals are plotted as a function of the total fluorescence/total luminescence ratio. Plotted results are from three independent experiments. (C) HEK-293 cells were transiently transected with plasmids encoding YFP-tagged neurofibromin PH domain as indicated. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed, and expression of PH domain was assessed by Western blot analysis. A representative Western blot of three independent experiments is illustrated.

Fig. 4.

Effects of PH domain mutations identified in NF1 patients and neurofibromin depletion in mice on 5-HT6 receptor-operated cAMP signaling. (A) HEK-293 cells were transfected with a constant amount of 5-HT6-RLuc construct and increasing concentrations of YFP-tagged PH domain constructs as indicated. Plotted results are from three independent experiments. (B) HeLa cells stably expressing neurofibromin shRNA were transiently transfected with 5-HT6 receptor construct in the absence or presence of YFP-tagged PH domain constructs as indicated. Data are means ± SEM of values obtained in a representative experiment performed in triplicate. Two other independent experiments performed on different cultures yielded similar results. ***P < 0.001 vs. neurofibromin-depleted cells transfected with empty vector. (C) Western blot analysis of neurofibromin and 5-HT6 receptor expression in PFC of WT and Nf1+/− mice. (D) cAMP production in PFC microdisks from WT and Nf1+/− mice treated with vehicle, SB271046, CPPQ, or WAY208466 (1 μM each). Data are means ± SEM of values obtained in three different mice. *P < 0.05 vs. microdisks from WT mice treated with vehicle; $$P < 0.01 vs. microdisks from Nf1+/− mice treated with vehicle. (E) CREB phosphorylation (at Ser133) in PFC of both mice strains treated for 30 min with vehicle, WAY208466, or SB271046 (10 mg/kg i.p. each) was analyzed by sequential immunoblotting using antiphospho-CREB and total CREB antibodies. Representative Western blots are illustrated in C and E. The data in E are means ± SEM of values measured in four mice per group. MW, molecular mass. *P < 0.05 vs. WT mice treated with vehicle; ***P < 0.001 vs. WT mice treated with vehicle.

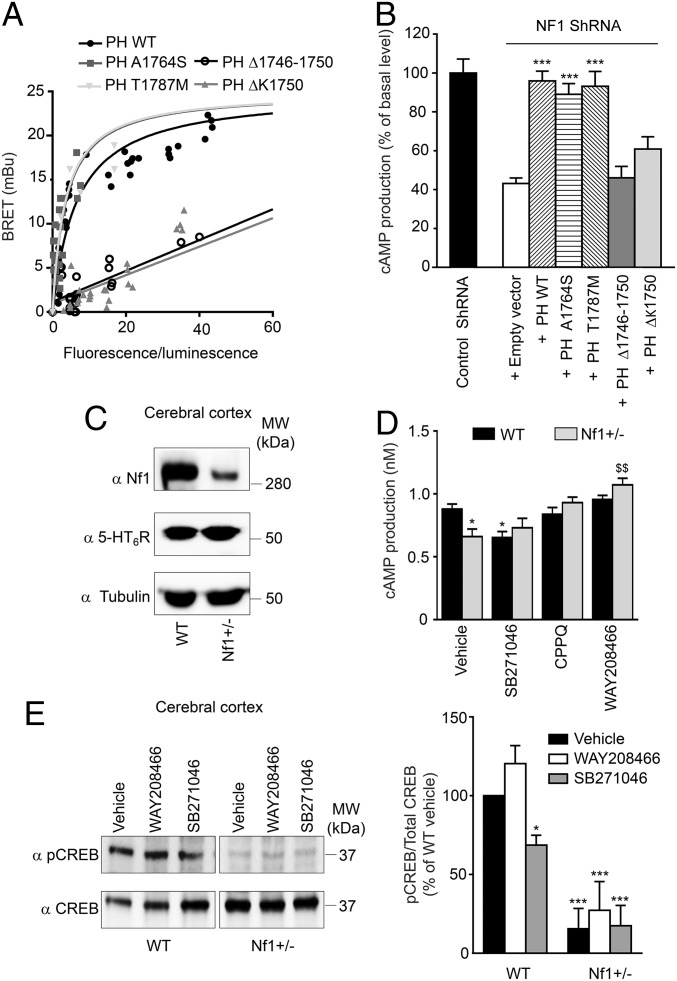

5-HT6 Receptor Constitutive Activity Is Impaired in a Mouse Model of Neurofibromatosis.

Whereas 5-HT6 receptor expression was not modified in Nf1+/− mice (Fig. 4C), we found a lower cAMP level in PFC compared with in WT mice (0.587 ± 0.026 vs. 0.441 ± 0.041 pmol/mg protein; n = 3, respectively). Treatment of PFC microdisks from WT mice with SB271046 (1 μM) decreased basal cAMP level but did not further reduce cAMP level in Nf1+/− mice (Fig. 4D). Further supporting a role of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity in brain cAMP production, (S)-1-[(3-chlorophenyl)sulfonyl]-4-(pyrrolidine-3-yl-amino)-1H-pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinolone (CPPQ), a recently described 5-HT6 receptor neutral antagonist (22), did not decrease cAMP production in either NG108-15 cells (Fig. S8A) or microdisks from WT and Nf1+/− mice (Fig. 4D). Exposure to WAY208466 slightly but not significantly enhanced cAMP production in microdisks from WT mice (Fig. 4D). A significant agonist-induced stimulation of cAMP production was only measured in PFC from Nf1+/− mice that exhibit a reduced level of receptor constitutive activity.

Fig. S8.

Influence of CPPQ and SB271046 on agonist-independent 5-HT6 receptor-operated Gs-cAMP signaling. (A) NG108-15 cells transfected with empty vector (Mock) or the plasmid encoding the 5-HT6 receptor were treated with vehicle, SB271046, or CPPQ (1 µM each) for 5 min. Data are means ± SEM of results obtained in a typical experiment performed in triplicate. Two other experiments performed on different sets of NG108-15 cells yielded similar results. ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle in 5-HT6 receptor-transfected cells. (B) WT mice were treated for 30 min with vehicle, CPPQ, or SB271046 (10 mg/kg i.p. each), and CREB phosphorylation (at Ser133) in PFC was analyzed by sequential immunoblotting using antiphospho-CREB and total CREB antibodies. The histogram represents means ± SEM of densitometric analyses of Western blots obtained from three mice per condition. *P < 0.05 vs. vehicle.

To further confirm the role of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity in activation of the cAMP pathway in vivo, we next measured the phosphorylation level of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) in PFC. Reminiscent of the impact of neurofibromin on cAMP level, CREB phosphorylation (at Ser133) was strongly reduced in PFC of Nf1+/− mice (−84 ± 13%) compared with WT mice (Fig. 4E). Systemic administration of SB271046 (10 mg/kg i.p.) also reduced the level of phosphorylated CREB in PFC of WT mice but to a lesser extent (−31 ± 6%; n = 3), whereas it had no effect on CREB residual phosphorylation level measured in PFC of Nf1+/− mice (Fig. 4E). This finding suggests that neurofibromin-dependent 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity at Gs signaling only partially contributes to basal CREB phosphorylation. As expected, treatment of WT mice with the neutral antagonist CPPQ (10 mg/kg i.p.) did not alter CREB phosphorylation (Fig. S8B), whereas administration of WAY208466 (10 mg/kg i.p.) induced a slight but not significant increase in CREB phosphorylation in both WT and Nf1+/− mice (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these results indicate that cAMP signaling is strongly affected in Nf1+/− mouse brain and that inhibition of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity contributes to this reduced cAMP production and the associated CREB phosphorylation.

SI Materials and Methods

Reagents.

Coelenterazine was from Interchim. The protease inhibitor mixture was from Roche. PVDF membrane and CL-X film were from GE Healthcare Life Sciences. Supersignal West Pico, and supersignal extended Dura chemiluminescent substrates were from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. CPPQ was synthesized according to the previously disclosed procedures (22). All other reagents and culture media were from Sigma Aldrich. NF1 siRNA (L-003916-00-0005) and control siRNA (D-001810-01-05) were from Dharmacon. Synthetic peptides (>90% purity) were purchased from Genscript. Peptide sequences were as follows: TAT Ct22 peptide: YGRKKRRQRRRPLFMRDFKRALGRFLPCPRCPR; and TAT control peptide: YGRKKRRQRRRRPCRPCPLFRGLARKFDRMFLP.

Antibodies.

The polyclonal antineurofibromin antibody (sc-67), the monoclonal antitubulin antibody, the antiphospho–CREB-1, and total CREB-1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; the anti-HA antibody was from Roche Diagnostics; the anti-Flag antibody was from Sigma Aldrich; the anti–5-HT6 receptor antibody (ab103016) was from Abcam; the antiphospho-ERK and total ERK were from Cell Signaling Technologies; and the anti-GFP antibody (Living Colors Full-Length GFP Polyclonal Antibody) was from Clontech. The goat anti-mouse, goat anti-rat, rabbit anti-goat, and goat anti-rabbit IgG HRP-linked whole antibodies were from Life Technologies. The anti-Flag and anti-HA affinity gels were from Sigma Aldrich, the antineurofibromin, and anti-IgG affinity gels were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and the anti-GFP affinity gel (GFP-Trap) was from Chromotek (Am Klopferspitz).

Animals.

Nf1+/− heterozygote mice (B6.129S6-Nf1tm1Fcr/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Knock-in mice expressing 5-HT6-GFP receptor and the methods used for experiments using these mice are described here. The procedures involving mice were approved by the local ethics committee on animal experimentations of the CNRS in Orleans, France (agreement CECO3 no. 1041).

5-HT6-GFP knock-in C57BL/6N mice expressing 5-HT6 receptor fused C-terminally to GFP were generated by homologous recombination by the Institut Clinique de la Souris (www.ics-mci.fr/en/). In these mice, the EGFP cDNA was introduced in frame at the end of exon 4 of the HTR6 gene, removing the receptor’s stop codon and generating a C-terminally tagged receptor. The GFP-tagged receptor showed membrane expression and functionality similar to the WT receptor. Notably, the tagged construct displayed the same constitutive activity levels and apparent affinity for serotonin as the WT receptor as measured using the cAMP cell-based assay kit (Cisbio) in NG108-15 cells: constitutive activity: 669 ± 1.5 pmol cAMP per 1 mg protein for the WT receptor vs. 635 ± 3.4 pmol/mg protein for the GFP-tagged construct; EC50 = 0.764 ± 0.065 nM for the WT receptor vs. 0.784 ± 0.026 nM for the GFP-tagged construct. Western blot analysis of 5-HT6-GFP receptor immunoprecipitated from brain tissue of 5-HT6-GFP mice showed expression of an EGFP-immunoreactive protein of expected size, and the distribution pattern of 5-HT6-GFP receptor in brain was concordant with previous ligand autoradiographic studies (36).

Cell Cultures and Transfections.

HEK-293T cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) dialyzed FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin.

Control HeLa SilenciX cells and NF1 HeLa SilenciX cells were from Tebu Bio and obtained after transfection with control shRNA or neurofibromin shRNA, respectively. Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) dialyzed FCS and 125 μg/mL hygromycin B (Invitrogen).

NG108-15 cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) dialyzed FCS and 2% (vol/vol) hypoxanthine/aminopterin/thymidine (Life Technologies). Striatal neurons were prepared from mouse embryos at embryonic day 15. Neurons were plated on polyornithine-coated plastic culture dishes (50,000 cells per 1 cm2) and grown in neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with B27 (Invitrogen) and 2 mM l-glutamine.

For BRET experiments, cells were transfected with the calcium phosphate precipitation method. For coimmunoprecipitation and cAMP determinations, cells were transiently transfected with 10 µg plasmid per 100-mm dish with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and Opti-MEM (Gibco) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Experiments were performed 24–48 h after transfection. For NG108-15 cells, HEK-293 cells, and primary neurons, siRNA was transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Coimmunoprecipitation Assays.

HEK-293 and NG108-15 cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA, Flag, or YFP fusion proteins. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed on ice for 30 min in lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, and the protease inhibitor mixture. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatants were incubated with anti-HA affinity gel or GFP-Trap Beads for 3 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer [200 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 6.8, 4% (wt/vol) SDS, 40% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.02% bromophenol blue, 0.5 M β-mercaptoethanol]. Striata dissected from mice brain were homogenized in lysis buffer. Samples were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatants were incubated with antineurofibromin or anti-IgG affinity gels for 3 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed five times with lysis buffer and resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer.

For coimmunoprecipitation of neurofibromin with 5-HT6-GFP receptor, 20 mg mice brain proteins solubilized in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1.3% (wt/vol) CHAPS, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche) were incubated overnight at 4 °C with 50 μL GFP-Trap Beads (Chromotek). Beads were washed five times successively with low- and high-salt buffers containing 50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4 and either 0.15 or 0.5 M NaCl, respectively. Immunoprecipitated proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody (1:500 dilution; Roche) and the polyclonal antineurofibromin antibody (1:1,000 dilution).

Western Blotting.

Total lysates and immunoprecipitates from transfected HEK-293 or NG108-15 cells or mouse brain were separated by SDS/PAGE [8%, 10%, or 15% (wt/vol) gels] and transferred electrophoretically to PVDF membranes (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Blots were probed with anti-HA, anti-GFP, antineurofibromin, or anti–5-HT6 receptor antibodies. HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-rat antibodies (1:33,000) were used as secondary antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were detected using the Pico or Dura Detection Kit. Protein quantification on blots was performed using Quantity One software (Biorad).

cAMP Determination.

cAMP accumulation in cell cultures was measured using the LANCE cAMP Detection Kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were harvested in HBSS containing 5 mM Hepes, 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, and 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4. After centrifugation (1,000 × g for 5 min), cells were resuspended in the same buffer (2 × 106 per 1 mL). The Alexa Fluor 647 anti-cAMP antibody solution (1 µL) was added to the cell suspension (100 µL), and 6-µL aliquots of the mixture were dispensed in white 384-well microtiter plates (Optiplate; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences). Cells were then stimulated with increasing concentrations of different drugs. After 1 h of incubation at room temperature in the dark, lysis buffer (0.35% Triton X-100, 10 mM CaCl2, 50 mM Hepes) containing LANCE EU-W8044–labeled streptavidin and biotinylated cAMP was added to the cells. After 2 h of incubation at room temperature in the dark, plates were read on a Victor Microplate Reader (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences). Concentration/response curves were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software.

Immunohistochemistry.

Adult 5-HT6-GFP mice were rapidly anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg i.p.; Ceva SA) and perfused transcardially with fixative solution containing 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Brains were then postfixed with the same solution for 4 d at 4 °C. Fifty-micrometer-thick sections were cut with a vibratome (Leica) and incubated for 1 h at room temperature in PBS supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum (NGS) and 1% Triton X-100 to block nonspecific sites. Sections were then incubated at 4 °C for 48 h under gentle agitation in primary antibody solution containing GFP booster coupled to Atto488 Fluorophore (1:200 dilution; Chromotek) and the rabbit polyclonal antineurofibromin antibody (1:50 dilution; SC-67; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in PBS, 5% (vol/vol) NGS, and 0.1% Triton X-100. Sections were then washed three times in PBS (10, 15, and 30 min) and incubated with an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody [1:1,000 dilution in PBS, 5% (vol/vol) NGS, 0.1% Triton X-100; Molecular Probes] for 4 h at room temperature. Sections were washed four times in PBS and mounted in ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Thermofisher Scientific). Fluorescent images were acquired using an AxioImager Z1 Microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRm Camera, and the Apotome Slider system with an H1 transmission grid (Carl Zeiss, Inc.) using the AxioVision software (Carl Zeiss, Inc.). Posttreatment of images (level correction), annotations, and panel composition were performed using Photoshop software (Adobe).

BRET Analyses.

Luminescence and fluorescence were detected using a Mithras LB 940 Multireader (Berthold), which allows the sequential integration of luminescence signals detected with two filter settings (RLuc filter, 485 ± 10 nm; YFP filter, 530 ± 12 nm). Emission signals at 530 nm were divided by emission signals at 485 nm. The BRET ratio was defined as the difference between the emission ratio obtained with cotransfected RLuc and YFP fusion proteins and that obtained with the RLuc fusion protein alone. The results were expressed in milliBRET units (mBU; with 1 mBU corresponding to the BRET ratio values multiplied by 1,000). BRETmax is the maximal BRET signal obtained in milliBRET units, and BRET50 represents the acceptor/donor ratio yielding 50% of the maximal BRET signal. Total fluorescence and luminescence were used as relative measures of total expressions of the YFP- and RLuc-tagged proteins, respectively. BRET signals were plotted as a function of the ratio between total fluorescence and total luminescence ratio.

SI Results

5-HT6 Receptor Recruits Neurofibromin via Its PH Domain and CTD.

To identify the region(s) in the neurofibromin sequence involved in its association with 5-HT6 receptor, a series of Flag-tagged constructs containing different domains of neurofibromin was expressed in HEK-293T cells and immunoprecipitated using anti-Flag M2 affinity gel. Five domains of neurofibromin were initially tested: N-terminal domain (NTD), GTPase-activating protein-related domain (GRD), GTPase-activating protein-related domain, region homologous to the yeast Sec14p protein domain, and Pleckstrin Homology domain (GRD-Sec-PH), Heat-like repeat (HLR), and CTD (Fig. S2A). As shown in Fig. S2B, 5-HT6 receptors strongly interacted with CTD and GRD-Sec-PH domains but not with GRD, NTD, and HLR. To determine which of the Sec and PH domains interacts with the receptor, we then expressed Flag-tagged versions of each domain separately and found that 5-HT6 receptors specifically coimmunoprecipitate with the PH domain (Fig. S2C).

Corroborating coimmunoprecipitation experiments, BRET analysis showed specific association of 5-HT6-YFP with PH domain and CTD of neurofibromin fused to RLuc (PH-RLuc: BRETmax = 25.6 ± 2.0 mBU, BRET50 = 15.2 ± 2.4; CTD-RLuc: BRETmax = 65.0 ± 2.8 mBU, BRET50 = 108.2 ± 14.1), whereas no specific BRET signal was detected in cells coexpressing 5-HT6-YFP and GRD or Sec domain fused to RLuc (Fig. S2D). Reciprocal studies using 5-HT6 receptor fused to RLuc as donor and neurofibromin Sec-PH domains or its PH domain alone fused to YFP as acceptors confirmed a robust interaction of 5-HT6 receptor with the Sec-PH and PH domains, which both display a higher affinity for the receptor (BRET50 = 11.5 ± 3.2 and 6.6 ± 1.4, respectively) compared with the CTD (BRET50 = 92.1 ± 27.9) (Fig. S3A).

Neurofibromin Interacts with the CTD of 5-HT6 Receptor.

To explore the contribution of this domain in the recruitment of neurofibromin by 5-HT6 receptor, we generated several truncation mutants (deleted of C-terminal residues) of the receptor (Fig. S4A) and expressed them in HEK-293 cells to evaluate their capacity to interact with endogenous neurofibromin. Deleting distal 27 (), 49 (), or 98 () amino acids of the 5-HT6 receptor CTD did not affect neurofibromin coimmunoprecipitation with the receptor, whereas truncation of the entire CTD (120 amino acids; ) abolished 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction (Fig. 2A). Likewise, no specific BRET signal was found between -YFP and PH-Rluc (Fig. 2B). This finding suggests an essential role of 22 N-terminal residues of the receptor CTD in 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction. Consistent with this hypothesis, coimmunoprecipitation studies showed that a receptor mutant deleted of these residues () (Fig. S4A) does not interact with the entire neurofibromin (Fig. S4B). Moreover, receptor fused to YFP did not generate a specific BRET signal with PH-RLuc, further supporting the importance of Y320-R342 residues in the interaction with neurofibromin PH domain (Fig. 2B).

Discussion

Using an unbiased proteomic strategy, we previously identified neurofibromin as a candidate partner of recombinant 5-HT6 receptor expressed in HEK-293 cells (12). In line with the common influence of 5-HT6 receptor and neurofibromin in brain development, learning and memory, and brain cAMP signaling (23, 24), we further characterized in this study 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction and showed that they form a complex in mouse brain. Moreover, we showed that 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction is a dynamic process that depends on receptor conformational state and can be prevented by a specific antagonist (SB271046), which thus behaves as an inverse agonist to disrupt this spontaneous (constitutive) association. Using BRET, we provided evidence that the PH domain and the CTD of neurofibromin independently interact with the receptor, suggesting that they contribute to the association of the receptor with full-length neurofibromin. Nonetheless, the higher affinity of PH domain for the receptor compared with CTD and the ability of the 5-HT6 inverse agonist to prevent association of 5-HT6 receptor with PH domain but not with CTD suggest a prominent role of PH domain in the interaction between both protein partners. PH-like domains have long been associated with proteins involved in signal transduction (25). Neurofibromin PH domain is adjacent to the central GTPase-activating protein-related domain and the Sec14-homologous Sec domain that interacts with glycerophospholipids (26). A hairpin-like protrusion of PH domain interacts with a helical lid segment of Sec domain and has been proposed to promote its binding to the lipid cage. However, neurofibromin PH domain alone cannot bind to lipids (26), whereas it is sufficient to associate with the 5-HT6 receptor, thus providing a demonstration of an Sec-independent function of this domain. Finally, we show that 22 N-terminal residues of the receptor CTD are essential for the association of neurofibromin with 5-HT6 receptor, consistent with numerous findings, which identified GPCR CTD as a key domain contributing to their association with GIPs (20). This 22-residue sequence comprises a stretch of four prolines that might be important for binding to neurofibromin PH domain (26).

In an effort to characterize the functional impact of the 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction, we showed that it promotes receptor constitutive activity at Gs signaling without affecting agonist-elicited cAMP production. Notably, neurofibromin similarly affects constitutive activity of human and mouse receptors, despite their divergent pharmacology and signal transduction properties. Indeed, down-regulating neurofibromin expression as well as any strategy leading to the disruption of the interaction between 5-HT6 receptor CTD and neurofibromin PH domain strongly reduced agonist-independent receptor-operated cAMP signaling in both heterologous cells expressing recombinant human 5-HT6 receptor and mice neurons expressing native receptors. Furthermore, reexpressing WT PH domain, but not mutant PH domains unable to interact with 5-HT6 receptor, rescued a normal level of receptor constitutive activity in neurofibromin-depleted cells. Collectively, these results suggest that 5-HT6 receptor association with neurofibromin maintains the receptor in a specific conformation, allowing the constitutive activation of Gαs protein and thereby, cAMP production through activation of adenylyl cyclase. Several lines of evidence support a role of PH-like domains present in other proteins in GPCR-operated signal transduction. For instance, the C-terminal one-half of GPCR Kinase 2 PH domain serves as a platform for G protein βγ-subunit binding (27). Whether the neurofibromin PH domain associated with 5-HT6 receptor favors recruitment of Gs protein remains to be explored. A recent study has shown that the regulation by neurofibromin of cAMP signaling requires Ras activation and operates through the activation of atypical PKC zeta (28), whereas other studies performed in Drosophila suggest that neurofibromin controls cAMP production in an Ras-independent manner (19, 29). Our results showing that expression of PH domain alone is sufficient to rescue normal 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity in neurofibromin-deficient cells are consistent with an Ras-independent mechanism. They also rule out a role for the CTD, which was previously shown to regulate adenylyl cyclase activity in Drosophila (16), in the constitutive activation of adenylyl cyclase by 5-HT6 receptor.

This study provides an example of modulation of GPCR constitutive activity by a GIP. Another example is the modulation of agonist-independent activity of group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1a and mGluR5) by the constitutively expressed Homer3 protein (30). In contrast to the 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction, the association of Homer3 with the CTD of mGluR1a or mGluR5 prevents the constitutive activation of these receptors, whereas the activity-dependent short Homer1a isoform behaves as a dominant negative regulator of the interaction between mGluR1a or mGluR5 and Homer3 and thereby, promotes constitutive activity of these receptors. Therefore, this work provides an example of constitutive activation of G protein signaling by a GPCR dependent on its physical association with a GIP.

The inability of neurofibromin mutants (mutated in PH domain) identified in NF1 patients to interact with 5-HT6 receptor and consequently, promote receptor constitutive activity suggests that agonist-independent 5-HT6 receptor-operated signaling might be altered in some NF1 patients. Corroborating this hypothesis, we found that CREB phosphorylation and to a lesser extent, cAMP level are diminished in Nf1+/− mice compared with WT mice and that the prototypic 5-HT6 receptor inverse agonist SB271046 does not further decrease this reduced cAMP level and CREB phosphorylation, whereas it affects basal cAMP level and CREB phosphorylation in WT mice. Further supporting a role of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity vs. receptor activation secondary to the release of its endogenous agonist (5-HT), cAMP production and CREB phosphorylation in mouse brain were not altered by the 5-HT6 receptor neutral antagonist CPPQ. Nonetheless, it is likely that other mechanisms in addition to reduction of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity at Gs signaling contribute to the strong decrease in CREB phosphorylation level in Nf1+/− mice. The alteration of cAMP signaling in Nf1+/− mice is also consistent with previous observations in Nf1 null Drosophila, which suggest that the associated learning deficits result from an inhibition of cAMP-mediated PKA activity (31, 32).

CREB has been identified as a key regulator of cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in the developing brain, and it has been involved in learning, memory, and neuronal plasticity in adult brain (33). Inhibition of cAMP signaling and the resulting CREB phosphorylation caused in part by the loss of 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity might thus contribute to neuronal abnormalities and cognitive impairment observed in NF1 patients. However, 5-HT6 receptor blockade by 5-HT6 receptor antagonists, improves cognition in a wide range of paradigms in rodents rather than it produces cognitive impairment. Another pathway engaged by 5-HT6 receptor that might contribute to cognitive impairment in NF1 patients is the mTOR pathway. Loss of neurofibromin Ras-GAP activity in NF1 leads to aberrant mTOR activation, which is essential for NF1-associated malignancies (34). Moreover, nonphysiological mTOR activation has been involved in cognitive deficits observed in several neurodevelopmental disorders (35). mTOR activation, under the control of 5-HT6 receptor, likewise underlies deficits in social cognition and episodic memory in rat developmental models of schizophrenia (12). mTOR activation by 5-HT6 receptors is critically dependent of its physical association with 5-HT6 receptor CTD. Neurofibromin might compete with mTOR to associate with 5-HT6 receptor because of the proximity of their target motif in the receptor sequence and thus, prevent engagement of mTOR signaling by the receptor. Consistent with this hypothesis, neurofibromin mutants unable to interact with 5-HT6 receptor identified in some NF1 patients would favor the recruitment of mTOR and receptor-operated mTOR signaling. Therefore, the contribution of 5-HT6 receptor in the enhanced mTOR signaling in NF1 certainly warrants additional exploration. Likewise, it would be of considerable interest to explore in future studies the impact of treatment with 5-HT6 receptor antagonists and mTOR inhibitors on the associated cognitive deficits.

In conclusion, this study provides evidence for a physical interaction between neurofibromin and a GPCR, the 5-HT6 receptor, and an example of modulation of constitutive activity of a GPCR through its interaction with a GIP. It also reveals a function of neurofibromin independent of its well-characterized Ras-GAP activity. Although the precise pathophysiological significance of 5-HT6 receptor–neurofibromin interaction and the resulting 5-HT6 receptor constitutive activity remain to be established, these findings suggest that it might be considered as a potentially relevant therapeutic target to correct some NF1-related deficits.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, plasmid constructs (Table S1), antibodies, and animals are detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Methods used for cell cultures, transfections, coimmunoprecipitation, and Western blot are described in SI Materials and Methods. The procedures involving mice were approved by the local ethics committee on animal experimentations of the CNRS in Orleans, France (agreement CECO3 n°1041).

Table S1.

List of plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Description | Source |

| p3xFlag | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Sigma Aldrich |

| pCDNA3 | AmpR, NeoR, Pro CMV | Sigma Aldrich |

| pEYFP-N1 | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Clontech |

| P3xFlag NTerm | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + NTD Nf1 (1-1168) | ||

| P3xFlag GAPSecPH5 | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + GRD-SecPH Nf1 (1169-1816) | ||

| P3xFlag GAP7 | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + GRD Nf1 (1169-1545) | ||

| P3xFlag SecPH | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 37 |

| + SecPH (1546-1816) | ||

| P3xFlag Sec | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + Sec (1546-1712) | ||

| P3xFlag PH | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + PH (1713- 1816) | ||

| P3xFlag HLR | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + HLR Nf1 (1817-2428) | ||

| P3xFlag CTerm | Tag Flag, AmpR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + CTD Nf1 (2429-2818) | ||

| PRK5-5-HT6 HA | Tag HA, AmpR, Pro CMV ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 12 |

| + 5HT6R | ||

| HA-5-HT6-YFP | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 13 |

| + 5HT6R | ||

| HA-5-HT6-Rluc | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + 5HT6R | ||

| HA-CTerm-YFP | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + CTD Nf1 (2429-2818) | ||

| HA-CTerm-Rluc | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + CTD Nf1 (2429-2818) | ||

| HA-SecPH-YFP | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + SecPH (1546-1816) | ||

| HA-SecPH-Rluc | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + SecPH (1546-1816) | ||

| HA-Sec-Rluc | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + Sec (1546-1712) | ||

| HA-Sec-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + Sec (1546-1712) | ||

| HA-PH-Rluc | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + PH (1713- 1816) | ||

| HA-PH-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| + PH (1713- 1816) | ||

| HA-5HT6ΔCt-YFP | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| +5HT6ΔCt | ||

| HA-5HT6 ΔY320-R342-YFP | Tag YFP, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| +5HT6 ΔY320-R342 | ||

| HA-5HT6R342 | Tag HA, AmpR, Pro CMV ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 12 |

| +5HT6R342 | ||

| HA-5HT6G391 | Tag HA, AmpR, Pro CMV ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 12 |

| +5HT6G391 | ||

| HA-5HT6R413 | Tag HA, AmpR, Pro CMV ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | Ref. 12 |

| +5HT6R413 | ||

| HA-PH R1748A-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH K1750A-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH Δ1750-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH R1764S-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH T1787M-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH Δ1746–1750-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

| HA-PH RΔ17191736-YFP | Tag Rluc, KanaR, Pro CMV, ORI eukaryote, ORI prokaryote | This study |

ORI, origin of replication.

BRET Measurements.

Forty-eight hours after transfection, HEK-293T cells resuspended in HBSS saline buffer (Invitrogen) were incubated for 15 min at 25 °C in the absence or presence of the indicated ligands. Coelenterazine H substrate (Molecular Probes) was added at a final concentration of 5 µM. Luminescence and fluorescence were detected using a Mithras LB 940 Multireader (Berthold). BRET measurement and calculation are described in SI Materials and Methods.

cAMP Determination.

cAMP accumulation in cell cultures was measured using the LANCE cAMP Detection Kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences) as described in SI Materials and Methods.

For cAMP measurement in brain tissue, the LANCE Ultra cAMP Kit (Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences) was used. Brains were rapidly extracted after animals were killed. Tissue samples were punched out from PFC slices (300-µm thick, obtained with a microtome) to obtain circular microdisks of 1.5-mm diameter. The microdisks were treated for 10 min with drugs diluted in the stimulation buffer (HBSS containing 5 mM Hepes, 1 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 1% BSA). After removal of buffer containing drugs, the microdisks were lysed and sonicated in cAMP detection buffer (provided in the kit). After centrifugation, samples were dispensed in white 384-well microtiter plates and incubated with solution containing ULight-anti–cAMP and Eu-cAMP for 1 h. Plates were read on a Victor Microplate Reader.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anthony Guillemain, Fabienne Godin, and Rudy Clemençon for technical assistance; Stéphane Mortaud for his help in the preparation of microdisks; and Catherine Grillon, Martine Decoville, and Elodie Robin for all discussions. This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche under Grant ANR-BLAN-SVSE4-LS-110627, CNRS, INSERM, the University of Orléans, and the University of Montpellier. W.D.N. was the recipient of a PhD fellowship from the French Ministry of Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1600914113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Codony X, Burgueño J, Ramírez MJ, Vela JM. 5-HT6 receptor signal transduction second messenger systems. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2010;94:89–110. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-384976-2.00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsden CA, King MV, Fone KC. Influence of social isolation in the rat on serotonergic function and memory--relevance to models of schizophrenia and the role of 5-HT₆ receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61(3):400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benhamú B, Martín-Fontecha M, Vázquez-Villa H, Pardo L, López-Rodríguez ML. Serotonin 5-HT6 receptor antagonists for the treatment of cognitive deficiency in Alzheimer’s disease. J Med Chem. 2014;57(17):7160–7181. doi: 10.1021/jm5003952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruat M, et al. A novel rat serotonin (5-HT6) receptor: Molecular cloning, localization and stimulation of cAMP accumulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;193(1):268–276. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohen R, Fashingbauer LA, Heidmann DE, Guthrie CR, Hamblin MW. Cloning of the mouse 5-HT6 serotonin receptor and mutagenesis studies of the third cytoplasmic loop. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;90(2):110–117. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Purohit A, Herrick-Davis K, Teitler M. Creation, expression, and characterization of a constitutively active mutant of the human serotonin 5-HT6 receptor. Synapse. 2003;47(3):218–224. doi: 10.1002/syn.10157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sebben M, Ansanay H, Bockaert J, Dumuis A. 5-HT6 receptors positively coupled to adenylyl cyclase in striatal neurones in culture. Neuroreport. 1994;5(18):2553–2557. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoeffter P, Waeber C. 5-Hydroxytryptamine receptors with a 5-HT6 receptor-like profile stimulating adenylyl cyclase activity in pig caudate membranes. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1994;350(4):356–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00178951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun HM, et al. The novel cellular mechanism of human 5-HT6 receptor through an interaction with Fyn. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(8):5496–5505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun HM, Baik JH, Kang I, Jin C, Rhim H. Physical interaction of Jab1 with human serotonin 6 G-protein-coupled receptor and their possible roles in cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(13):10016–10029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.068759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SH, et al. Direct interaction and functional coupling between human 5-HT6 receptor and the light chain 1 subunit of the microtubule-associated protein 1B (MAP1B-LC1) PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meffre J, et al. 5-HT(6) receptor recruitment of mTOR as a mechanism for perturbed cognition in schizophrenia. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4(10):1043–1056. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duhr F, et al. Cdk5 induces constitutive activation of 5-HT6 receptors to promote neurite growth. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(7):590–597. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobshagen M, Niquille M, Chaumont-Dubel S, Marin P, Dayer A. The serotonin 6 receptor controls neuronal migration during corticogenesis via a ligand-independent Cdk5-dependent mechanism. Development. 2014;141(17):3370–3377. doi: 10.1242/dev.108043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bockaert J, Perroy J, Bécamel C, Marin P, Fagni L. GPCR interacting proteins (GIPs) in the nervous system: Roles in physiology and pathologies. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:89–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannan F, et al. Effect of neurofibromatosis type I mutations on a novel pathway for adenylyl cyclase activation requiring neurofibromin and Ras. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(7):1087–1098. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa RM, et al. Mechanism for the learning deficits in a mouse model of neurofibromatosis type 1. Nature. 2002;415(6871):526–530. doi: 10.1038/nature711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui Y, et al. Neurofibromin regulation of ERK signaling modulates GABA release and learning. Cell. 2008;135(3):549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo HF, Tong J, Hannan F, Luo L, Zhong Y. A neurofibromatosis-1-regulated pathway is required for learning in Drosophila. Nature. 2000;403(6772):895–898. doi: 10.1038/35002593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bockaert J, Marin P, Dumuis A, Fagni L. The ‘magic tail’ of G protein-coupled receptors: An anchorage for functional protein networks. FEBS Lett. 2003;546(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00453-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claeysen S, Sebben M, Becamel C, Bockaert J, Dumuis A. Novel brain-specific 5-HT4 receptor splice variants show marked constitutive activity: Role of the C-terminal intracellular domain. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55(5):910–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grychowska K, et al. Novel 1H-pyrrolo[3,2-c]quinoline based 5-HT6 receptor antagonists with potential application for the treatment of cognitive disorders associated with Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7(7):972–983. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutmann DH, Parada LF, Silva AJ, Ratner N. Neurofibromatosis type 1: Modeling CNS dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2012;32(41):14087–14093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3242-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dayer AG, Jacobshagen M, Chaumont-Dubel S, Marin P. 5-HT6 receptor: A new player controlling the development of neural circuits. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2015;6(7):951–960. doi: 10.1021/cn500326z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheffzek K, Welti S. Pleckstrin homology (PH) like domains - versatile modules in protein-protein interaction platforms. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(17):2662–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Angelo I, Welti S, Bonneau F, Scheffzek K. A novel bipartite phospholipid-binding module in the neurofibromatosis type 1 protein. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(2):174–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lodowski DT, et al. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction studies of a complex between G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and Gbeta1gamma2. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59(Pt 5):936–939. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903002622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anastasaki C, Gutmann DH. Neuronal NF1/RAS regulation of cyclic AMP requires atypical PKC activation. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(25):6712–6721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker JA, et al. Genetic and functional studies implicate synaptic overgrowth and ring gland cAMP/PKA signaling defects in the Drosophila melanogaster neurofibromatosis-1 growth deficiency. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(11):e1003958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ango F, et al. Agonist-independent activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors by the intracellular protein Homer. Nature. 2001;411(6840):962–965. doi: 10.1038/35082096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo HF, The I, Hannan F, Bernards A, Zhong Y. Requirement of Drosophila NF1 for activation of adenylyl cyclase by PACAP38-like neuropeptides. Science. 1997;276(5313):795–798. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The I, et al. Rescue of a Drosophila NF1 mutant phenotype by protein kinase A. Science. 1997;276(5313):791–794. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory: cAMP, PKA, CRE, CREB-1, CREB-2, and CPEB. Mol Brain. 2012;5:14. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerjee S, Crouse NR, Emnett RJ, Gianino SM, Gutmann DH. Neurofibromatosis-1 regulates mTOR-mediated astrocyte growth and glioma formation in a TSC/Rheb-independent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(38):15996–16001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bockaert J, Marin P. mTOR in brain physiology and pathologies. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(4):1157–1187. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00038.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberts JC, et al. The distribution of 5-HT(6) receptors in rat brain: An autoradiographic binding study using the radiolabelled 5-HT(6) receptor antagonist [(125)I]SB-258585. Brain Res. 2002;934(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02360-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vallée B, et al. Nf1 RasGAP inhibition of LIMK2 mediates a new cross-talk between Ras and Rho pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]