Abstract

This study investigated whether the nurturing hypothesis – that breastfeeding serves as a proxy for family socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours – accounts for the association of breastfeeding with children's academic abilities. Data used were from the Child Development Supplement of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which followed up a cohort of 3563 children aged 0–12 in 1997. Structural equation modelling simultaneously regressed outcome variables, including three test scores of academic ability and two subscales of behaviour problems, on the presence and duration of breastfeeding, family socio‐economic characteristics, parenting behaviours and covariates. Breastfeeding was strongly related to all three tests scores but had no relationships with behaviour problems. The adjusted mean differences in the Letter–Word Identification, Passage Comprehension) and Applied Problems test scores between breastfed and non‐breastfed children were 5.14 [95% confidence interval (CI): 3.14, 7.14], 3.46 (95% CI: 1.67, 5.26) and 4.24 (95% CI: 2.43, 6.04), respectively. Both socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours were related to higher academic test scores and were associated with a lower prevalence of externalising and internalising behaviour problems. The associations of breastfeeding with behaviour problems are divergent from those of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours. The divergence suggests that breastfeeding may not be a proxy of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours, as proposed by the nurturing hypothesis. The mechanism of breastfeeding benefits is likely to be different from those by which family socio‐economic background and parenting practices exert their effects. Greater clarity in understanding the mechanisms behind breastfeeding benefits will facilitate the development of policies and programs that maximise breastfeeding's impact.

Keywords: academic ability, breastfeeding, behaviour problems, child development

Introduction

The importance of breastfeeding on a multitude of child development outcomes has been consistently validated in the literature, and the association between breastfeeding and increased cognitive development is widely acknowledged (e.g. Anderson et al. 1999; Kramer et al. 2008). Recent studies with more rigorous approaches have attempted to identify the causal relationship between breastfeeding and child outcomes and have generally found positive effects of breastfeeding on cognitive development (Borra et al. 2012; Fitzsimons & Vera‐Hernández 2012).

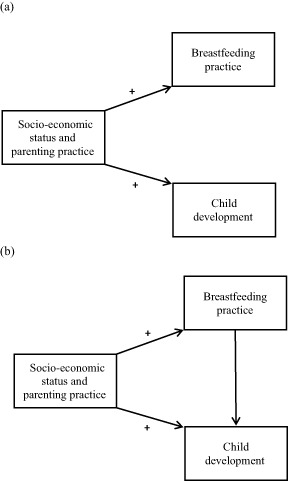

However, the mechanism by which breastfeeding improves child development has been debated, with researchers discussing both nutritional and nurturing links from breastfeeding (Gibbs & Forste 2014). On the one hand, increased cognitive development for breastfed infants may result from nutritional benefits of breastfeeding. For example, long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) found naturally in breast milk are necessary for neurodevelopment (Uauy & De Andraca 1995; Cockburn 2003; Der et al. 2006; Petryk et al. 2007; Zhou et al. 2007). On the other hand, it has been argued that breastfeeding may only serve as a proxy for family socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours (see Fig. 1a) that have important effects on child development (Der et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2007; Gibbs & Forste 2014). It is established that privileged mothers have a greater probability to breastfeed than less privileged mothers (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010; Der et al. 2006). A higher probability of breastfeeding is associated with supportive parenting behaviours as well. As infant‐to‐mother skin contact during breastfeeding has been found to be correlated with improved parent–child interaction (Uauy & De Andraca 1995; Jain et al. 2002; Petryk et al. 2007), a higher probability of breastfeeding is in effect associated with higher levels of supportive parenting behaviours. Suggested by this nurturing hypothesis, the link between breastfeeding and cognitive development may just be a reflection of the impacts of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

Figure 1.

Socio‐economic status, parenting practice, breastfeeding and child development: (a) proxy process and (b) mediation process.

Several studies provide evidence to support the nurturing hypothesis. Der et al. (2006) used the data from the U.S. National Longitudinal Survey of Youth and found that the association of breastfeeding with cognitive ability of children aged 5–14 became small and non‐significant after controlling for family income, mothers' education and IQ, and parenting behaviours (emotional support and cognitive stimulation). Zhou et al. (2007) collected data from a cohort of about 300 children in Australia and suggested that the duration of breastfeeding had no relationship with children's IQ at age 4, while the quality of the home environment, which included aspects of parents' emotional support and cognitive stimulation to children, was the strongest predictor of IQ. One recent study (Gibbs & Forste 2014) also confirmed that the positive correlation between breastfeeding and school readiness of children at age 4 disappeared after controlling for mothers' education, emotional support and cognitive stimulation. In addition, Gibbs and Forste (2014) demonstrated that breastfeeding did not improve school readiness among children whose mothers had low education in the data from the U.S Early Childhood Longitudinal Study‐Birth Cohort.

A strategy applied in these three studies was to adjust the association of breastfeeding with cognitive development through controlling for socio‐economic characteristics (e.g. family income and parents' education) and parenting behaviours (e.g. emotional and cognitive support) in the regression analyses. One concern of this strategy is that the nurturing hypothesis, or breastfeeding as a proxy of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours, may not be the only theory that can explain the attenuated relationship between breastfeeding and cognitive development after adjustment. An alternative explanation of the adjusted association is a mediation process (Fig. 1b), in which advantageous socio‐economic status and supporting parenting behaviours increase the probability of breastfeeding, and breastfeeding practice promotes children's cognitive development. If socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours are highly correlated with the probability of breastfeeding children in this mediation process, the inclusion of socio‐economic indicators and parenting behaviours in analyses is likely to greatly attenuate or even explain the association of breastfeeding with cognitive development despite the fact that breastfeeding practice does promote cognitive development. That is, the weakened relationship between breastfeeding and cognitive development after adjusting for socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours does not necessarily indicate that breastfeeding has no impacts at all. Figure 1 illustrates the proxy process and the mediation process, both of which could predict the weakened association of breastfeeding with cognitive development after adjusting for socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

The objective of this study thus was to further investigate the nurturing hypothesis (i.e., the proxy process in Fig. 1a) on the link between breastfeeding and child development in the context of family socio‐economic background and parenting behaviours. Specifically, we explored the associations of breastfeeding with children's academic ability and behaviour problems (i.e., poor behaviour) and compared them with those of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours. As discussed in detail in the following section, the inclusion of a different child development outcome from cognitive development may provide important insights into the investigation of the nurturing hypothesis.

Key messages.

The association of breastfeeding with children's academic ability is statistically positive after adjusting for family socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

The associations of breastfeeding with children's behaviour problems are divergent from those of family socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours, which suggest that the nurturing hypothesis may not be the primary mechanism of breastfeeding's impact on child development.

Interventions, such as peer counselling programmes, should be promoted to increase rates of breastfeeding and support child development.

Materials and methods

Sample

We used the data from the Child Development Supplement (CDS) of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a longitudinal survey that collects demographic information and socio‐economic characteristics from a nationally representative sample in the United States. Beginning in 1997, the PSID supplemented its core data with additional information from a group of children 0–12 years old (N = 3563) in the CDS to examine the dynamic process of early human development. The same children were interviewed three times in 1997, 2002 and 2007, respectively, if they were still younger than age 18 at the time of each interview. The recruiting, eligibility and attrition of the PSID‐CDS have been described elsewhere (Wright et al. 2001). The CDS collected retrospective breastfeeding information of children in the first wave (1997). It also conducted standardised academic ability tests on children older than 5, and measured externalising and internalising behaviour problems for children older than 3 in all three waves.

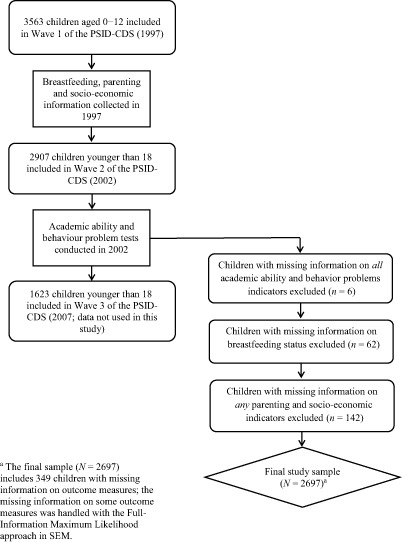

We included all CDS children who were interviewed in 2002 (N = 2907) because it provided the largest sample for analysis among the three waves. Compared with the second wave, a proportion of children were excluded from the third wave in 2007 due to age ineligibility, resulting in a smaller sample size (N = 1623). In the first wave of the PSID‐CDS, a proportion of children (e.g. those younger than 3), however, did not have valid information on standardised academic ability tests and behaviour problems. The study further limited the sample to children who had valid information on (1) any indicators of academic ability tests or behaviour problems in the second wave (2002) and (2) all predictor variables and covariates listed in Table 1. The final sample size was 2697; 210 children were excluded from the study due to missing information on family income and mother's education. The final sample includes 349 children with missing information among indicators of academic ability and behaviour problems. The Full‐Information Maximum Likelihood method (Muthén et al. 1987) was applied to address the missing information on these measures. Figure 2 presents the sample selection process in a flow chart.

Table 1.

Weighted characteristics of the analytic sample: PSID‐CDS, 1997 and 2002 (N = 2697)

| Variables* | Mean (SD) or % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole sample | Breastfed (n = 1208) | Not breastfed (n = 1489) | |

| Outcome variables (measured in 2002) | |||

| WJ‐R LW score (n = 2440) † | 106.2 (19.0) | 109.7 (18.8) | 101.1 (18.1) |

| WJ‐R PC score (n = 2386) † | 104.8 (17.5) | 107.1 (17.8) | 101.2 (16.4) |

| WJ‐R AP score (n = 2449) † | 105.0 (17.3) | 108.4 (17.1) | 100.4 (16.6) |

| Externalising behaviours (n = 2688) † | 5.6 (4.2) | 5.4 (4.0) | 6.0 (4.4) |

| Internalising behaviours (n = 2674) | 3.3 (3.2) | 3.3 (3.2) | 3.4 (3.3) |

| Major predictor variables | |||

| Whether children were breastfed (%) | 58.8 | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding (month) | 3.3 (4.1) | ||

| Emotional support to children † | 9.8 (2.1) | 10.0 (2.1) | 9.5 (2.1) |

| Cognitive stimulation to children † | 9.7 (2.3) | 10.0 (2.3) | 9.5 (2.2) |

| Mother's education (%) † | |||

| High school and below | 51.5 | 45.6 | 61.4 |

| Some college | 26.2 | 25.6 | 25.5 |

| 4‐year college and above | 22.4 | 28.8 | 13.1 |

| Family income † | 51 373.7 (48 801.8) | 57 474.7 (50 946.4) | 42 846.2 (44 278.5) |

| Covariates | |||

| Children's characteristics | |||

| Race (%) † | |||

| White | 64.8 | 70.5 | 56.5 |

| Black | 15.5 | 6.7 | 28.3 |

| Others | 19.7 | 22.9 | 15.2 |

| Gender (male; %) | 49.0 | 48.9 | 50.7 |

| Age in years (measured in 2002) | 10.1 (3.7) | 10.2 (3.6) | 10.1 (3.6) |

PSID‐CDS, Panel Study of Income Dynamics–Child Development Supplement; WJ‐R LW, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Letter–Word Identification test; WJ‐R PC, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Passage Comprehension test; WJ‐R AP, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Applied Problems test. *All variables were measured in the 1997 PSID‐CDS except for those specified in the table. †The difference between breastfed and non‐breastfed children is statistically significant at the 0.001 level.

Figure 2.

Sample selection flow chart.

Outcome variables

Academic ability was measured by the scores of three subtests of the Woodcock–Johnson Revised (WJ‐R) Tests of Achievement administered in the second wave of the CDS (2002). Two subtests on reading ability – the Letter–Word Identification (LW) and the Passage Comprehension (PC) – and one subtest on math ability – the Applied Problems (AP) – were conducted on the PSID‐CDS children older than age 5. The raw scores of reading and math tests were standardised across age to a 0–200 continuous variable, respectively. The WJ‐R Tests of Achievement has been widely used and has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (Woodcock 1990).

Behaviour problems were indicated by a 32‐item Behavior Problem Index (BPI) adopted in the second wave of the CDS from the scale developed by Peterson & Zill (1986). The BPI asked the primary caregiver whether a set of children's problem behaviours (e.g. having sudden changes in mood or feeling, being fearful or anxious, bullying, demanding excessive attention) was often, sometimes or never true. The index was split into two subscales measuring externalising or aggressive behaviours and internalising or withdrawn behaviours. Possible scores range from 0 to 17 for the externalising subscale, and from 0 to 15 for the internalising subscale. The two subscales had Cronbach's alpha values above 0.80.

Predictor variables

All predictor variables were measured in the first wave of the CDS (1997) when children were 0–12 years old. Reported by primary caregivers, breastfeeding practice was indicated by a dichotomous variable on whether children were breastfed or not (‘1’ for yes and ‘0’ for no). We used the dichotomous measure because it is less likely to carry recall errors for this retrospective information. This strategy, using a dichotomous indicator of breastfeeding to increase reliability, has been applied in previous research (e.g. Der et al. 2006; Zhou et al. 2007). We also used two measures of the duration of breastfeeding – a continuous variable of 0–12 months and a three‐level categorical variable (0 months, 1–6 months and 7 months and above) – in supplemental tests, and consistent results were obtained.

To indicate parenting behaviours, we used two separate variables – emotional support and cognitive stimulation – obtained from the Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment–Short Form, a reliable and valid standardised measure to assess the caring environment for children (Totsika & Sylva 2004). Similar measures were used in previous research testing the nurturing hypothesis (e.g. Der et al. 2006; Gibbs & Forste 2014). Emotional support and cognitive stimulation were based on observed interactions between mothers and children in the home environment by well‐trained interviewers employed by the PSID program. Emotional support ranged from 2 to 14 and was summarised from survey items such as ‘mother caressed, kissed, or hugged child at least once’ and ‘mother conversed with child at least twice.’ Cognitive stimulation ranged from 2 to 14 and included items such as ‘how many books child has read’ and ‘mother provided toys or interesting activities.’ Having demonstrated their validity and reliability in previous surveys (e.g. the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth), both measures of emotional support and cognitive stimulation had Cronbach's alpha values greater than 0.80.

Family socio‐economic background was indicated by mother's education and family income. Mother's education was categorised into three groups (high school and below, some college, and college degree and above). As family income is positively skewed, we applied the logarithmic transformation on the income variable.

Covariates

All covariates were measured in the first wave of the CDS (1997). We adjusted for children's demographic characteristics, including race (White, Black, and others), gender (female and male) and age. We added additional covariates in supplemental tests, such as children's preterm birth (1 = yes and 0 = no), low birthweight (1 = below 2500 g and 0 = others), neonatal intensive care at birth (1 = yes and 0 = no) and physical/mental limitations (1 = yes and 0 = no); mother's age and employment status (1 = employed and 0 = others); and family size and number of children in the family. Children's physical/mental limitations were defined by whether children had physical/mental conditions that limit them in play, school attendance or school work. The inclusion of extensive covariates in supplemental tests did not change the relationships between predictor variables and outcome variables.

Statistical analyses

Following descriptive analyses, we conducted Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis in Mplus 7.0 using Maximum Likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (Muthén & Muthén 2012) to explore the relationships between predictor variables and five outcome variables. All statistical analyses were weighed to account for the oversampling of minority children and data attrition. As discussed earlier, the missing information on outcome variables (n = 349) was estimated using the Full‐Information Maximum Likelihood method, a model‐based solution for missing data that handles missing values and estimates model parameters in one single step (Muthén et al. 1987).

Two sets of SEM analyses were conducted. In the first set, we simultaneously regressed five outcome variables, including three academic test scores and two subscales of behaviour problems, on a dichotomous indicator of breastfeeding and children's demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender and race). The associations between breastfeeding practice and child outcomes estimated in this set of analyses did not adjust for socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

The second set of SEM analyses then added indicators of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours into the first set. Previous investigations have found socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours to be related to higher levels of children's cognitive development (Britton et al. 2006; Gutman et al. 2009) but lower prevalence of behaviour problems (Hart et al. 1998; Stormshak et al. 2000). We thus hypothesised that socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours were positively related to academic ability and negatively related to behaviour problems. If breastfeeding serves as a proxy for socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours, as proposed by the nurturing hypothesis in Fig. 1a, the associations of breastfeeding with children's academic abilities and behaviour problems are likely to have the same directions as those of socio‐economic and parenting variables. In addition, the inclusion of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours in the second set is likely to weaken the associations between breastfeeding practice and child outcomes. Nonetheless, if associations between breastfeeding and child outcomes have a pattern different from those of socio‐economic and parenting indicators, it might imply that the nurturing hypothesis is not likely to be the major mechanism by which breastfeeding improves cognition.

Several supplemental analyses were conducted to test the robustness of our findings. All of these supplemental tests adjusted for indicators of children's demographic characteristics, family socio‐economic background and parenting behaviours. Firstly, two measures of the duration of breastfeeding were used to replace the dichotomous indicator of breastfeeding in the analyses. Secondly, we limited our analyses, respectively, to a subsample of children younger than 8 years and a subsample of children whose mothers had education not greater than high school. Thirdly, we used the list‐wise deletion approach and missing indicator approach to address the missing information in child outcome measures, resulting in sample sizes of 2348 and 2901, respectively. Finally, we included additional covariates, such as children's health and disability conditions and mother's employment status, in the second set of SEM analyses.

Results

As shown in Table 1, in the study sample, the mean scores were 106.2 (SD = 19.0), 104.8 (SD = 17.5) and 105.0 (SD = 17.3), respectively, for the LW, the PC and the AP tests. On average, children in the sample had an externalising behaviour subscale value of 5.6 (SD = 4.2) and an internalising behaviour subscale value of 3.3 (SD = 3.2). Nearly 60% of children were breastfed, and the mean duration of breastfeeding was 3.3 months. The mean scores for emotional support and cognitive stimulation to children were 9.8 (SD = 2.1) and 9.7 (SD = 2.3), respectively. Slightly more than half of the mothers had a high school degree or below, and the average family income was above $50 000 (SD = $48 802) in 1997. In terms of children's demographic characteristics, about 65% of the sampled children were White and nearly half were male. The average age of children in 2002 was 10 years old (SD = 3.7). We also report sample characteristics by children's breastfeeding status in Table 1. Breastfed children had statistically higher scores in all three academic ability tests and a statistically lower score in the externalising behaviour subscale than non‐breastfed children (P < 0.001). Compared with those not breastfed, breastfed children were also more likely to be White, have mothers with a higher level of education, live in families with a higher income and receive stronger emotional support and cognitive stimulation from their parents.

Table 2 presents the results of two sets of SEM analyses and several supplemental tests. The first set of SEM analyses, as shown in panel A, estimated the association between breastfeeding and child outcomes only controlling for children's age, gender and race. The mean differences in test scores for breastfed children and non‐breastfed children were 6.80 [95% confidence interval (CI): 4.81, 8.79; P < 0.001], 4.72 (95% CI: 2.90, 6.54; P < 0.001) and 6.00 (95% CI: 4.17, 7.83; P < 0.001), respectively, for the LW, PC and AP tests. However, breastfed and non‐breastfed children did not have significant differences in subscales of externalising (−0.41, P = 0.08) and internalising (−0.18, P = 0.31) behaviour problems.

Table 2.

Predicting child development using breastfeeding, parenting and socio‐economic characteristics (N = 2697)

| Variables |

WJ‐R LW test b (95% CI) P‐value |

WJ‐R PC test b (95% CI) P‐value |

WJ‐R AP test b (95% CI) P‐value |

Externalising b (95% CI) P‐value |

Internalising b (95% CI) P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Not adjusted by parenting and family background | |||||

| Whether children were breastfed (Yes) |

6.80*** (4.81, 8.79) <0.001 |

4.72*** (2.90, 6.54) <0.001 |

6.00*** (4.17, 7.83) <0.001 |

−0.41 † (−0.87, 0.05) 0.08 |

−0.18 (−0.52, 0.17) 0.31 |

| R 2 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Panel B: Adjusted by parenting and family background | |||||

| Whether children were breastfed (Yes) |

5.14*** (3.14, 7.14) <0.001 |

3.46*** (1.67, 5.26) <0.001 |

4.24*** (2.43, 6.04) <0.001 |

−0.14 (−0.60, 0.32) 0.56 |

−0.00 (−0.36, 0.35) 0.99 |

| Parenting indicators | |||||

| Emotional support to children |

−0.01 (−0.70, 0.79) 0.98 |

0.05 (−0.56, 0.66) 0.87 |

0.27 (−0.33, 0.88) 0.38 |

−0.21** (−0.35, −0.06) <0.01 |

−0.15** (−0.27, −0.03) <0.01 |

| Cognitive stimulation to children |

0.77*** (0.30, 1.24) <0.001 |

0.96*** (0.55, 1.37) <0.001 |

0.89*** (0.42, 1.36) <0.001 |

−0.11 † (−0.23, 0.02) 0.08 |

−0.07 † (−0.16, 0.01) 0.10 |

| Family socio‐economic indicators | |||||

| Mother's education (reference group: High school and below) | |||||

| Some college |

4.77*** (2.33, 7.20) <0.001 |

4.19*** (2.13, 6.25) <0.001 |

4.05*** (1.93, 6.16) <0.001 |

−0.39 (−0.89, 0.11) 0.13 |

−0.19 (−0.60, 0.22) 0.36 |

| 4‐year college and above |

7.87*** (5.26, 10.49) <0.001 |

5.06*** (2.71, 7.41) <0.001 |

7.80*** (5.51, 10.09) <0.001 |

−0.77*** (−1.34, −0.20) <0.001 |

−0.57** (−1.00, −0.14) <0.01 |

| Log‐transformed income |

1.40*** (0.38, 2.43) <0.001 |

0.85 † (−0.05, 1.74) 0.06 |

1.14*** (0.45, 2.37) <0.001 |

−0.34** (−0.57, −0.11) <0.01 |

−0.17 † (−0.37, 0.03) 0.09 |

| R 2 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Panel C: Months of breastfeeding | |||||

| Duration of breastfeeding (0–12 months) |

0.31** (0.11, 0.50) <0.01 |

0.29*** (0.12, 0.46) <0.001 |

0.36*** (0.18, 0.50) <0.001 |

0.03 (−0.03, 0.03) 0.17 |

−0.00 (−0.03, 0.03) 0.99 |

| Panel D: Categorical measure of breastfeeding | |||||

| Categorical measure of breastfeeding (reference category: No breastfeeding) | |||||

| 1–6 months |

3.57*** (1.89, 5.25) <0.001 |

2.39** (0.82, 3.96) <0.01 |

3.08*** (1.64, 4.53) <0.001 |

−0.11 (−0.48, 0.28) 0.59 |

−0.13 (−0.41, 0.16) 0.40 |

| 7 months and above |

3.67*** (1.57, 5.78) <0.001 |

3.33*** (1.43, 5.22) <0.001 |

4.07*** (2.18, 5.96) <0.001 |

−0.37 (−0.81, 0.08) 0.11 |

−0.10 (−0.45, 0.26) 0.60 |

| Panel E: Subsample of young children (age < 8, n = 620) | |||||

| Whether children were breastfed (Yes) |

5.81*** (2.40, 9.21) <0.001 |

3.12* (0.22, 6.01) 0.04 |

9.16*** (5.21, 13.10) <0.001 |

0.22 (−0.60, 1.04) 0.60 |

0.35 (−0.32, 1.01) 0.31 |

| Panel F: Subsample of low‐education mothers (n = 1528) | |||||

| Whether children were breastfed (Yes) |

6.61*** (4.23, 8.99) <0.001 |

3.77*** (1.15, 6.34) <0.001 |

5.87*** (3.47, 8.26) <0.001 |

−0.54 (−1.21, 0.13) 0.12 |

−0.17 (−0.68, 0.34) 0.52 |

| Panel G: List‐wise selection (n = 2348) | |||||

| Whether children were breastfed (Yes) |

5.17*** (3.14, 7.20) <0.001 |

3.48*** (1.69, 5.27) <0.001 |

4.08*** (1.73, 5.87) <0.001 |

−0.19 (−0.69, 0.31) 0.45 |

−0.07 (−0.44, 0.31) 0.73 |

WJ‐R LW, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Letter–Word Identification test; WJ‐R PC, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Passage Comprehension test; WJ‐R AP, Woodcock–Johnson Revised Applied Problems test. Five regression models were conducted simultaneously in each panel. Analyses in all panels were adjusted for children's age, gender and race. Parenting and socio‐economic indicators were adjusted in analyses from panel B to panel G. The inclusion of additional covariates (e.g. preterm birth, low birthweight, neonatal intensive care, physical/mental limitations, mother's age, employment status, household's size and number of children) in sensitivity tests did not change the relationships between predictor variables and outcome variables. Model fit indices of SEM analyses [the comparative fit index = 1.00, Tucker‐Lewis Index = 1.00, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.00 (90% CI: 0.00 to 0.00), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual = 0.00] suggested that overall the model fits the sample data well. † P < 0.1, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

The second set of analyses (reported in panel B) included socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours as predictor variables. After controlling for these variables, the mean differences in test scores for breastfed children and non‐breastfed children were 5.14 (95% CI: 3.14, 7.14), 3.46 (95% CI: 1.67, 5.26), and 4.24 (95% CI: 2.43, 6.04), respectively, for the LW, PC and AP tests; all differences are statistically significant at P < 0.001. Still, breastfed and non‐breastfed children did not have significant differences in subscales of externalising and internalising behaviour problems. The inclusion of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours reduced the magnitude of regression coefficients on the variable of breastfeeding, but did not remove its significance on academic ability test scores.

As expected, academic supportive parenting behaviours (mainly cognitive stimulation to children) were associated with higher academic test scores. Supportive parenting behaviours were correlated to lower prevalence of behaviour problems as well. One point increase in cognitive stimulation raised the LW test score by 0.77 points (95% CI: 0.30, 1.24; P < 0.001), and one point increase in emotional support reduced the subscale of externalising behaviour problems by 0.21 points (95% CI: −0.35, −0.06; P < 0.001). More advantageous socio‐economic status (indicated by higher family income or mothers' educational attainment) was related to higher levels of academic ability and lower levels of behaviour problems. For example, after controlling for other variables in SEM analysis, children whose mothers graduated from college or above had an AP test score 7.87 points (95% CI: 5.26, 10.49; P < 0.001) higher than those whose mothers had a high school degree or below. While breastfeeding, parenting behaviours and socio‐economic characteristics were all positively related to academic ability, the associations of breastfeeding with behaviour problems clearly were different from those of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

The results of supplemental tests are consistent with those reported in panel B. All of these supplemental tests adjusted for parenting behaviours and socio‐economic indicators. As demonstrated in panels C and D, both measures of the duration of breastfeeding had positive associations with WJ‐R test scores but had no associations with two subscales of behaviour problems. Similar findings were obtained from the subsamples of young children (age < 8, n = 620), children whose mother had low‐level of education (n = 1528) and those with full information on all outcome variables (n = 2348).

Discussion

Previous research has investigated the association of breastfeeding, separately, with cognitive development and behaviour problems and generally found consistent results with our study – breastfeeding was positively associated with academic tests but had no relationships with behaviour problems (Borra et al. 2012; Fitzsimons & Vera‐Hernández 2012). Our study makes unique contributions by examining the associations of breastfeeding with these two outcomes simultaneously in the context of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours.

The inclusion of behaviour problems as a child development outcome in analyses is valuable in investigating the nurturing hypothesis of breastfeeding benefits. The nurturing hypothesis was proposed mainly because breastfeeding, family socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours all are positively associated with cognitive development, and breastfeeding is likely to be confounded with socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours. This suggests that, without an appropriate identification strategy, only examining the adjusted association of breastfeeding with cognitive development is difficult to distinguish the nurturing hypothesis from other possible mechanisms. The inclusion of behaviour problems in the model, however, provided an opportunity to further explore the nurturing hypothesis. If breastfeeding serves as a proxy for parenting behaviours and other environmental factors, as suggested in Fig. 1a by the nurturing hypothesis, then the associations of breastfeeding with behaviour problems should be negative and statistically significant, similar to those of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours. This is because when socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours are not presented in the model (e.g., panel A of Table 2), breastfeeding practice is just an indicator of these factors. Our results show a clear divergence in the associations of behaviour problems with breastfeeding, parenting behaviours and socio‐economic characteristics. Both socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours are negatively related to children's subscale values of externalising and internalising behaviour problems, but breastfeeding had no relationships with behaviour problems. Such divergence is less likely to be caused by the mechanism in which breastfeeding is a proxy of socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours. What these results suggest is that the mechanism behind the observed relationship between breastfeeding and child development is likely to be different from those by which family socio‐economic background and parenting behaviours exert their effects. The results of the SEM analysis do not support the nurturing hypothesis; this may instead indicate that the effect of breastfeeding observed in the literature is likely to reflect other mechanisms, such as the nutritional effect of breastfeeding practices.

The relationship between breastfeeding and academic ability adjusted for socio‐economic characteristics and parenting behaviours in the PSID‐CDS is also stronger than those estimated from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (Der et al. 2006) and the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study‐Birth Cohort (Gibbs & Forste 2014), another two nationally representative samples in the United States. Breastfeeding was statistically and positively associated with all three test scores of academic ability in the second set of SEM analyses (panel B of Table 2). This might be caused by different covariates controlled in analyses and a different age range for the PSID‐CDS children. Nonetheless, similar results were obtained in supplemental analyses when we limited our sample to younger children and children of low‐education mothers and when we added additional covariates.

The study has limitations. The breastfeeding decision could still be an endogenous variable in the analyses and may raise the concern of selection bias. Some confounding factors may not be controlled in the analyses, and there may be recall bias for the retrospective measure of breastfeeding. About 7% of sample participants were excluded from the analysis and may affect the findings' external validity. In addition, it may be possible that breastfeeding practice affects different child outcomes in distinct ways. For example, if the nurturing hypothesis only works specifically for cognitive development but not all other child development outcomes universally, the study findings should be interpreted carefully. Despite the limitations, our results suggest that the primary mechanism of breastfeeding on development outcomes is still not clear and should be further explored. Promoting supportive parenting behaviours and improving socio‐economic status may not completely reduce the gap in cognitive development between breastfed and non‐breastfed children. Thus, exploring ways to increase breastfeeding and important nutritional substrates such as DHA throughout the population are perhaps important interventions to promote cognitive development. Interventions such as peer counselling programmes, which provide new mothers with the emotional and informational support to continue breastfeeding, have been shown to significantly increase rates of breastfeeding (Kistin et al. 1994; Arlotti et al. 1998).

Source of funding

The authors are grateful for support from the Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk, the Institute on Educational Sciences grants (R324A100022 & R324B080008) and from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50 HD052117).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributions

JH conceptualized the study question and approach, carried out the data analyses, drafted most of the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MGV drafted the abstract, the conclusion section and part of the implication section, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. KPK drafted parts of the introduction and discussion sections, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for support from the Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk, the Institute on Educational Sciences grants (R324A100022 and R324B080008) and from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50 HD052117).

Huang, J. , Vaughn, M. G. , and Kremer, K. P. (2016) Breastfeeding and child development outcomes: an investigation of the nurturing hypothesis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 12: 757–767. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12200.

References

- Anderson J.W., Johnstone B.M. & Remley D.T. (1999) Breast‐feeding and cognitive development: a meta‐analysis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 70, 525–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlotti J., Cottrell B., Lee S. & Curtin J. (1998) Breastfeeding among low‐income women with and without peer support. Journal of Community Health Nursing 15, 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borra C., Lacovou M. & Sevilla A. (2012) The Effect of Breastfeeding on Children's Cognitive and Noncognitive Development. The Institute for the Study of Labor: Bonn, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Britton J.R., Britton H.L. & Gronwaldt V. (2006) Breastfeeding, sensitivity, and attachment. Pediatrics 118, e1436–e1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010) Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state – National Immunization Survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 59, 327–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn F. (2003) Role of infant dietary long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, liposoluble vitamins, cholesterol and lecithin on psychomotor development. Acta Paediatrica 442, 19–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der G., Batty G.D. & Deary I.J. (2006) Effect of breast feeding on intelligence in children: prospective study, sibling pairs analysis, and meta‐analysis. British Medical Journal 333, 945–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons E. & Vera‐Hernández M. (2012) The Causal Effects of Breastfeeding on Children's Development. Institute for Fiscal Studies: London. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs B. & Forste R. (2014) Breastfeeding, parenting, and early cognitive development. The Journal of Pediatrics 164, 487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman L.M., Brown J. & Akerman R. (2009) Nurturing Parenting Capability: The Early Years. Centre for Research on the Wider Benefits of Learning, Institute of Education, University of London: London. [Google Scholar]

- Hart C.H., Nelson D.A., Robinson C.C., Olsen F.S. & McNeilly‐Choque M.K. (1998) Overt and relationship aggression in Russian nursery school‐age children: parenting style and marital linkages. Developmental Psychology 34, 687–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A., Concato J. & Leventhal J.M. (2002) How good is the evidence linking breastfeeding and intelligence? Pediatrics 109, 1044–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin N., Abramson R. & Dublin P. (1994) Effect of peer counselors on breastfeeding initiation, exclusivity, and duration among low income urban women. Journal of Human Lactation 10, 11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer M.S., Aboud F., Mironova E., Vanilovich I., Platt R.W., Matush L. et al (2008) Breastfeeding and child cognitive development. Archives of General Psychiatry 65, 578–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B., Kaplan D. & Hollis M. (1987) On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika 52, 431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. & Muthén B. (2012) Mplus. The Comprehensive Modelling Program for Applied Researchers: User's Guide, 7th edn Muthén and Muthén: Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J.L. & Zill N. (1986) Marital disruption, parent‐child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family 48, 295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Petryk A., Harris S.R. & Jongbloed L. (2007) Breastfeeding and neurodevelopment. Infants & Young Children 20, 120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak E.A., Bierman K.L., McMahon R.J., Lengua L.J. & the Conduct Problems Research Group (2000) Parenting problems and child disruptive behavior problems in early elementary school. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 29, 17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika V. & Sylva K. (2004) The home observation for measurement of the environment revisited. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 9, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uauy R. & De Andraca I. (1995) Human milk and breast feeding for optimal mental development. The Journal of Nutrition 125, 2278S–2280S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock R.W. (1990) Theoretical foundations of the WJ‐R measures of cognitive ability. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 8, 231–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wright J.C., Huston A.C., Vandewater E.A., Bickham D.S., Scantlin R.M., Kotler J.A. et al (2001) American children's use of electronic media in 1997: a national survey. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 22, 31–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.J., Baghurst P., Gibson R.A. & Makrides M. (2007) Home environment, not duration of breast‐feeding, predicts intelligence quotient of children at four years. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 23, 236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]