Abstract

The aim of the study was to identify Bacillus species from the Demodex folliculorum of patients with topical steroidinduced facial rosaceiform dermatitis. Of the 75 patients examined, 20% had clinical spinulosis, while 18.66% had dermoscopic features of Demodex: follicular plugs and tails. Of the 17.33% positive patients identified upon microscopy for Demodex, samples for bacterial culture were plated on trypticase soy Colombia agar. Identification was performed by microorganisms grown method mass spectrometry. We identified a strain of Bacillus cereus.

Keywords: Dermoscopy; Facial dermatoses; Mass spectrometry; Mite infestations; Receptors, steroid; Rosacea

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus oleronius isolated from Demodex folliculorum has been identified as a trigger of inflammation in rosacea.1 Skin lesions associated with an abnormal increase in Demodex mites, classified as secondary demodicosis, occur mostly in patients undergoing treatment with topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors.2

The aim of the study was to assess the microbioma in patients with topical steroid-induced facial rosaceiform dermatitis(TSIFRD) and the possible association between Bacillus and Demodex species.

METHODS

Patients with TSIFRD were included in this study, entailing clinical examination, dermoscopy and microscopy analysis of Demodex species. Furthermore, skin biopsies were performed on patients with inflammatory lesions. For the microscopic examination, samples were harvested from the affected area using a piece of Scotch transparent tape measuring 2cm, which was subsequently displayed in a microscope slide and examined under optical microscopy (10x-40x Zeiss). The sample for bacterial culture was spun two minutes and plated (trypticase soy agar and Columbia agar with 5% sheep's blood (Oxoid – Thermo Fischer, UK), then incubated at 37ºC for 48 hours. Identification was performed by microorganisms grown method MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Time-of-Flight ionization - Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). Colonies were transferred, emulsified and centrifuged, the supernatant was removed and the residue reconstituted in 70% formic acid. Measurements were performed using MALDI-TOF MS Microflex LT through the FlexControl software. The spectra were collected and analyzed via the Biotyper database (database [DB] -5627 Species list). Scores of above 2 were considered significant for genus and species identification. Mass spectrometry was used to identify the genus and species. The local ethics committee approved the study.

RESULTS

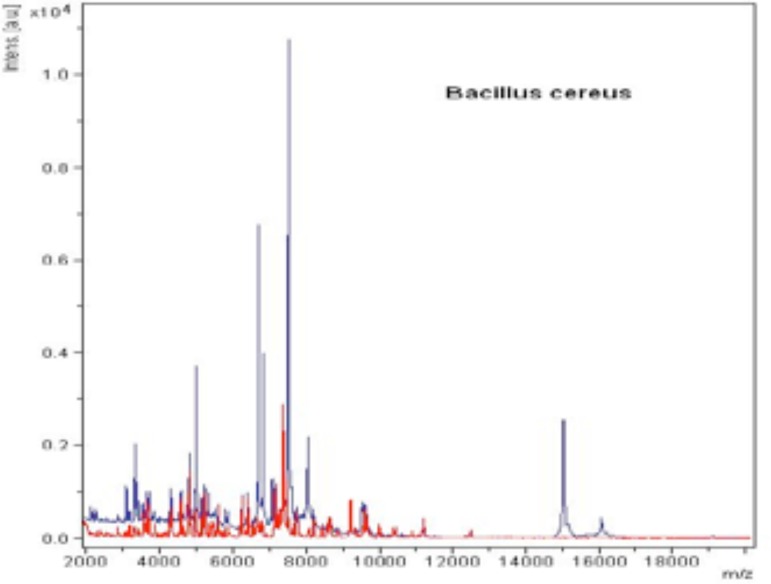

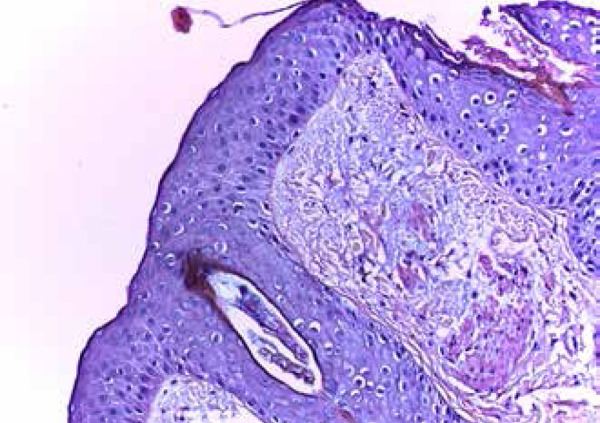

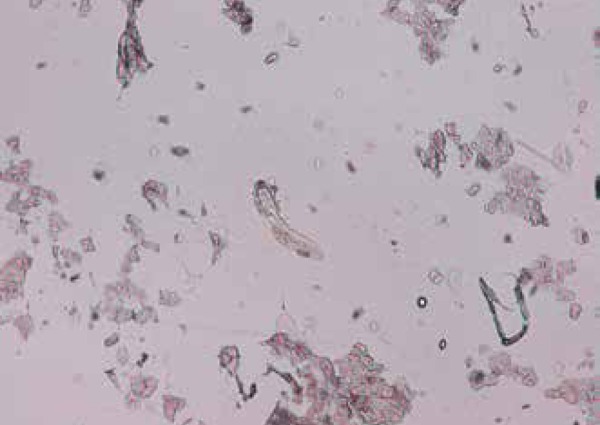

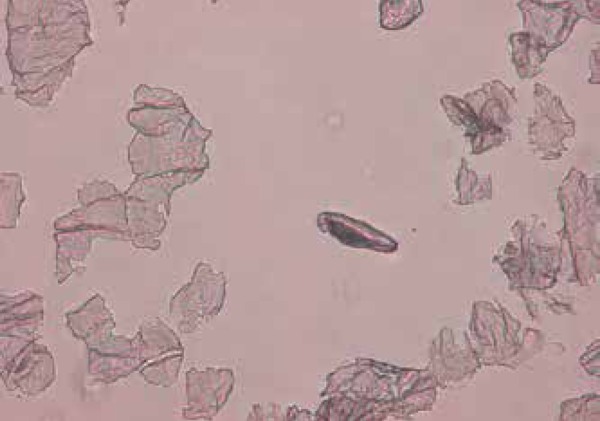

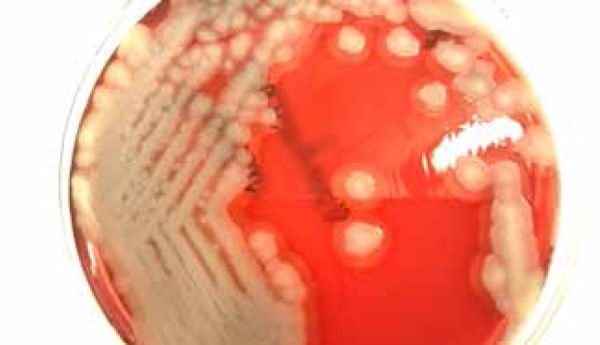

Seventy-five patients with variable TSIFRD subtypes were examined. Dermoscopy revealed: telangiectasias (100% of patients), pustules (80%), scales (54.66%) and atrophy (20%), as white structureless patches between vessels. Clinical spinulosis was found in 15 patients (20%), of which 14-18.66% bore dermoscopic features of Demodex: follicular plugs and Demodex tails (Figures 1 and 2). A biopsy performed on one spinulosis area showed a histopathologically characteristic image (Figure 3). Thirteen patients (17.33%) were positive for Demodex upon microscopy: 8 for D. folliculorum and 5 for D. brevis (Figures 4 and 5). Among the 8 patients with D. folliculorum, one had positive Bacillus cereus cultures. No B. oleronius or any other bacillus species were found. An analysis of the macroscopic diagnosis of bacterial cultures of the Bacillus species oriented morphology B. cereus colonies, which were dull gray and opaque, with a rough matted surface.The genus and species were identified by mass spectrometry (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 1.

Spinulosis of the face

Figure 2.

Dermoscopic follicular plugs and Demodex tails

Figure 3.

Histopathology of spinulosis revealed Demodex folliculorum; hematoxylin/eosine staining,40x

Figure 4.

Demodex folliculorum smear,10x

Figure 5.

Demodex brevis smear,20x

Figure 6.

Bacillus cereus culture at 72 hours on Colombia agar with 5% sheep's blood

Figure 7.

The spectrum obtained from the identification of Bacillus cereus by MALDI-TOF spectrometry

DISCUSSION

B. oleronius was isolated from only one dissected Demodex harvested from one patient with papulopustular rosacea.3 The absence of serum reactivity to Bacillus spp. antigens in 20% of patients with initial rosacea, along with the presence of antibodies in 40% of the controls without visible rosacea (as recorded in previous studies), raises questions about the role of these bacteria as atrigger of the post-steroid rosacea inflammatory process.4 B. cereus is a Gram-positive, aerobic-to-facultative, spore-forming rod widely distributed environmentally, bearing close phenotypic and genetic (16S rRNA) links to several other Bacillus species, especially B. anthracis.5 One reservoir for B. cereus is the intestinal tract of invertebrates. It has been observed in the guts of certain arthropods which is regarded as the normal intestinal stage in soil-dwelling insects attached to the arthropod intestinal epithelium, where they sporulate. 6,7 In the food industry, B. cereus spores are particularly troublesome because spores can be refractory to pasteurization and gamma radiation, while their hydrophobic nature allows them to adhere to surfaces.8 B. cereus spores may colonize skin on the hands and feet, which are often in contact with the environment through microscopic skin abrasions.The pathogenicity of B. cereus is intimately associated with tissue-destructive or reactive exoenzyme production: four hemolysins, three phospholipases, one emesis-inducing toxin, and three enterotoxins: hemolysin BL (HBL), nonhemolytic enterotoxin (NHE) and cytotoxin K.9 In 2008,Dohmae et al. described a B. cereus nosocomial infection from reused towels in Japan.10 This study focused on the correlation between D. folliculorum and types of Bacillus species.The low density of Demodex species in the patients included in the study could explain the lack of identification of B. oleronius culture, which may underline the difference of microbiome between typical rosacea and TSIFRD.

CONCLUSIONS

In a series of 75 patients with topical steroid-induced facial rosaceiform dermatitis (TSIFRD), 15 had clinical spinulosis, 14 had dermoscopic features of D. folliculorum - follicular plugs, Demodex tails confirmed by scraping, microscopy and histopathology. Eight out of 15 patients had D. folliculorum, and one case revealed associations with positive B. cereus cultures; while no B. oleronius was isolated. These results show a possible difference between the microbiome found in TSIFRD and previously reported data on microbiome in rosacea. Larger studies are needed to confirm correlations between Demodex and Bacillus species in different forms of rosacea and their implication in the inflammatory process.q

Funding Statement

Financial Support: Acknowledgements: This paper is supported by the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development(SOP HRD), financed by the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under the contract POSDRU/159/1.5/S/137390/

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none

Financial Support: Acknowledgements: This paper is supported by the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Resources Development(SOP HRD),financed by the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under the contract POSDRU/159/1.5/S/137390/

Work performed at the University Dunarea de Jos, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy; Central Reference Laboratory Synevo, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila – Bucharest, Romania.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen W, Plewig G. Human demodicosis: revisit and a proposed classification. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1219–1225. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antille C, Saurat JH, Lübbe J. Induction of rosaceiform dermatitis during treatment of facial inflammatory dermatoses with tacrolimus ointment. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:457–460. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lacey N, Ní Raghallaigh S, Powell FC. Demodex mites - commensals, parasites or mutualistic organisms? Dermatology. 2011;222:128–130. doi: 10.1159/000323009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Reilly N, Menezes N, Kavanagh K. Positive correlation between serum immunoreactivity to Demodex-associated Bacillus proteins and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:1032–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Auger S, Ramarao N, Faille C, Fouet A, Aymerich S, Gohar M. Biofilm formation and cell surface properties among pathogenic and nonpathogenic strains of the Bacillus cereus group. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6616–6618. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00155-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jensen GB, Hansen BM, Eilenberg J, Mahillon J. The hidden lifestyles of Bacillus cereus and relatives. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:631–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Margulis L, Jorgensen JZ, Dolan S, Kolchinsky R, Rainey FA, Lo SC. The arthromitus stage of B cereus: intestinal symbionts of animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:1236–1241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson A, Granum PE, Rönner U. The adhesion of Bacillus cereus spores to epithelial cells might be an additional virulence mechanism. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;39:93–99. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakai C, Iuchi T, Ishii A, Kumagai K, Takagi T. Bacillus cereus brain abssesses occurring in severely neutropenic patients: successful treatment with antimicrobial agents, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and surgical drainage. Intern Med. 2001;40:654–657. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dohmae S, Okubo T, Higuchi W, Takano T, Isobe H, Baranovich T, et al. Bacillus cereus nosocomial infection from reused towels in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2008;69:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]