Abstract

Depressed facial scars are still a challenge in medical literature, despite the wide range of proposed treatments. Subcision is a technique that is frequently performed to improve this type of lesions. This article proposes a new method to release depressed scars, reported and named by the author as dermal tunneling. This study presents a simple and didactic manner to perform this method. The results in 17 patients with facial scars were considered promising. Thus, the technique was deemed to be safe and reproducible.

Keywords: Cicatrix, Collagen, Fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Changes in color, texture, elasticity, and uniformity of the skin surface, which occurs in the presence of scars, are secondary to inflammatory alterations that affect the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis, in block or separately. These sites are, therefore, the target of the proposed treatment.1 Several techniques and technologies have been used to correct these sequelae, and the combination of procedures seems to provide better results.2 Subcutaneous incision, or subcision, is an effective technique for the correction of depressed scars. Initially described by Orentreich and Orentreich (1995), this technique is based on the rupture of fibrotic tissue and the trigger of an inflammatory reaction, with bleeding, which culminates in the production of collagen.3,4 Needles with unique characteristics have been used by different authors to perform this technique, including 19 G, 20 G, 21 G, and 18 G 1.5 Nokor, providing specific technical advantages in their experiments.4,5,6 Adverse effects may be observed immediately after the procedure, such as edemas, hematomas, pain, or, later, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, hypercorrection of the treated depressed scar, and fibrotic nodules.4 Complications may be avoided or conducted properly when intervention is performed by an experienced and judicious professional.7 The author proposes loosening fibrotic tissues at the dermis level of depressed scars using a new instrument and an easily executable methodology, which we have named dermal tunneling (TD®). The instrument used to perform TD® is a 1.20 X 25mm 18G X 1" sterile aspiration needle (Figure 1). Treatment should be performed in a procedure room that is thoroughly prepared for a surgical intervention. Initially, the area to be treated is marked, considering the tracing of four straight lines that meet at their ends, forming a diamond shape, which encompasses the entire depressed scar. Antisepsis with chlorhexidine 2%, followed by anesthesia with 2% lidocaine without a vasoconstrictor agent, are then performed at the four corners of the diamond shape. The aspiration needle is then introduced into transepidermal pathways, at dermal level depth, in a tunnel route, with a consequent rupture of fibrotic tissues. The needles moves back and forth, starting at the vertexes, called "A", towards the center of the diamond shape, called "B", creating a tunnel with each movement (Figure 1). The following tunnel is formed by the same rule, starting at the other three vertexes, so that the columns cross one another, until the entire area has been loosened (Figure 1). The group was evaluated retrospectively, from January 2013 to January 2015, including charts of 12 female and 5 male patients with facial depressed scars, and treated with TD®, in accordance with the methodology described above, performed by the same physician. The patients ranged from 23 to 48 years of age. Photographic documentation was performed by the same researcher, using the same digital camera, immediately after and two months after the procedure. After the procedure, patients received micropore dressings at the diamond-shaped vertexes, which were removed on the following day. Patients were only instructed to apply FPS 60 industrial sunscreen on the sites.

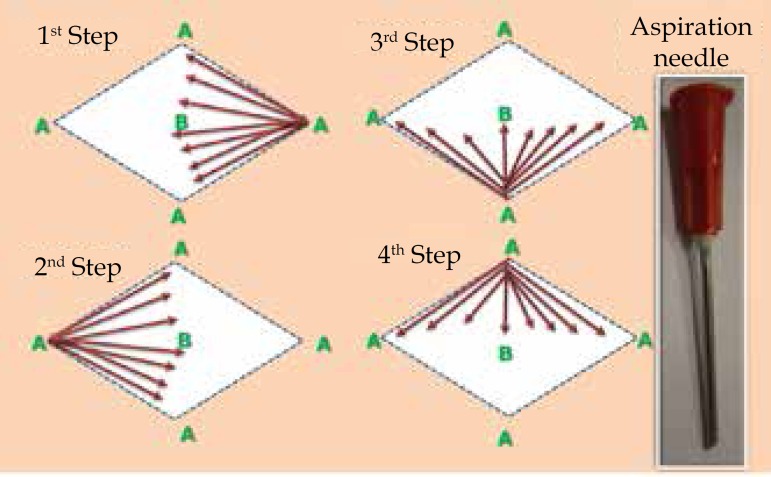

Figure 1.

Methodology proposed for TD®. The scheme shows the routing of the aspiration needle, starting at the diamond shape vertexes, A, toward the center, B

RESULTS

All of the patients reported being satisfied with the results and the autor considered the results to be evaluated as good to very good. The pain felt during treatment was considered quite tolerable. Patients returned to their work activities between the fifth and seventh day after the procedure, with a significant reduction of edema and hematoma. No complications, such as infection, hypercorrection, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, or persistent fibrotic nodules, were observed in this group (Figure 2). Among the patients evaluated, seven have undergone follow-up for 24 months and have maintained satisfactory results.

Figure 2.

Patients with depressed acne scars and inflammatory post-acne flaccidity, before (B) and after (A) dermal tunneling (TD®) treatment.

DISCUSSION

Despite the many proposals, depressed scar treatment is still a great challenge. The author proposes a new surgical approach to treat these lesions, in an attempt to optimize the results observed with current loosening techniques, thus standardizing an intervention methodology that may be reproduced by other physicians in a large number of patients. Therefore, the author concludes that TD®, following the methodology described above by the creator of this new therapeutic proposal, was considered an effective treatment for depressed scars. Results were promising and compatible with the author's and the patients' expectations, which allows to suggest the inclusion of this methodology proposed in the therapeutic arsenal for depressed scars. The pain and discomfort reported by the patients' post-surgery were compatible with that expected for such procedures The absence of post-surgical complications motivates the author to treat new patients in a similar manner. The author suggests the technique be evaluated in other patient groups to confirm the results and the conclusions provided in this article.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Financial Support: None

Work conducted at the Recife Santa Casa de Misericórdia Hospital, Recife, PE, Brazil.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goodman GJ. Postacne scaring: a review of its pathophysiology and treatment. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:857–871. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper JS, Lee BT. Treatment of facial scaring lasers , filler, and nonoperative techniques. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:311–315. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orentreich DS, Orentreich N. Subcutaneuos incisionless (subcision) surgery for correction of depressed scars and wrinkles. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1995.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hexsel DM, Mazzuco R. Subcision: uma alternativa cirúrgica para a lipodistrofia ginóide (celulite) e outras alterações no relevo corporal. An Bras Dermatol. 1997;77:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 5.AlGhamdi KM. A better way to hold a Nokor needle during subcision. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:378–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balighi K, Robati RM, Moslehi H, Robati AM. Subcision in acne scar with and without subdermal implant: a clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:707–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hexsel DM, Mazzuco R. Subcision: a treatment for celulite. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:539–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]