Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) may present with subtle clinical findings. Recognition of the imaging features of an impending rupture is key for timely diagnosis. This report reviews the classic computed tomography findings of impending AAA rupture and presents a recent case which illustrates the key features.

Keywords: abdominal aortic aneurysm, rupture, imaging, case report, review, hyperattenuating crescent, mural thrombus, aorta

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a dilation of the subdiaphragmatic aorta to a diameter greater than 3.0 cm. AAAs are found in 4–7% of men and 1% of women aged 50 and older (1). Although AAA is more common in men, women with AAA have a higher mortality rate, and more frequently present with a ruptured AAA (2). When AAAs rupture, the mortality rate is approximately 81% (3); therefore, efforts have been made toward early detection, especially in men aged over 65 with a smoking history, who, as a group, have the highest prevalence of AAA. Current screening guidelines from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend one-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography in men aged 65–75 who have ever smoked. The USPSTF recommends that clinicians selectively offer screening for AAA in men aged 65–75 who have never smoked rather than routinely screening all men in this group. In women, the USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for AAA in women aged 65–75 who have ever smoked. For women who are non-smokers, the USPSTF does not recommend screening (1, 4). When an AAA has been identified, intervention with open surgery or endovascular aneurysm repair is indicated when there is a significant risk of rupture (5).

Despite screening, undiagnosed aneurysms frequently present in the emergency department and inpatient settings. As many as 80% of aneurysmal ruptures occur in previously undiagnosed aneurysms (6). Unstable aneurysms are critical to recognize, as an impending rupture may have subtle or few warning signs. Pertinent features of the patient's history, bedside ultrasound, and knowledge of key computed tomography (CT) imaging signs can help physicians recognize patients at risk of rapid deterioration.

Case report

A 67-year-old male with a history of non-obstructive coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and bronchiectasis presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain of 8 h duration. He had no documented history of hypertension, and his medications included atorvastatin 20 mg daily and aspirin 81 mg daily. He described an aching pain in the lower abdomen which was sharp at times. He denied nausea, melena, hematochezia, or diarrhea. The patient had a 48 pack-year smoking history.

The patient's vital signs were within normal ranges. On physical examination, the patient was in mild discomfort due to abdominal pain. His pulses were intact and symmetrical in the upper and lower extremities. His abdomen was soft, with tenderness in the left lower quadrant. No pulsatile mass was present.

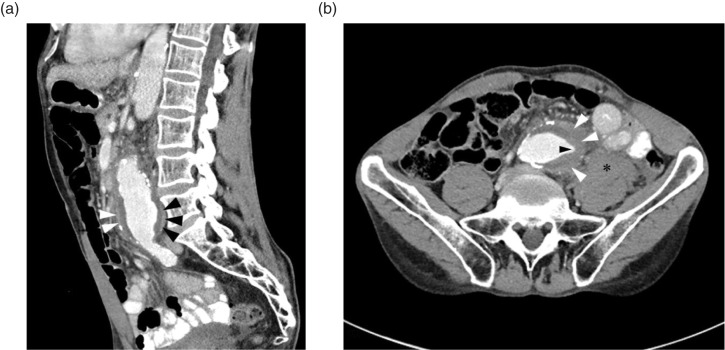

A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous iodinated contrast was performed, which revealed an infrarenal AAA measuring 6.5 cm in diameter. There was extensive mural thrombus, a patent lumen, and no evidence of frank rupture. There was a sharp, focal extension of the opacified lumen extending into the mural thrombus, and a hyperattenuating crescent in the wall of the thrombus (Fig. 1). Adjacent to the aneurysm, there was stranding of the mesenteric fat, as well as a collection of fluid obscuring the anterior margin of the psoas muscle (Fig. 1). The results of the scan were immediately relayed to the emergency physician.

Fig. 1.

(a) Sagittal CT of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast shows a 6.5 cm AAA with the ‘hyperattenuating crescent sign’ seen on both the anterior (white arrowheads) and posterior (black arrowheads) margin of the aorta. (b) Axial CT of the abdomen with contrast shows an AAA with a focal fissure extending into the mural thrombus (black arrowhead) and the ‘hyperattenuating crescent sign’ seen as a crescent-shaped area of enhancement (white arrowheads) in the lateral margin of the thrombus. The anterior margin of the psoas muscle is obscured by a blood collection (asterisk), representing a sentinel leak.

Within 15 min of the scan, the patient suddenly collapsed while ambulating. He was unconscious and pulseless, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated. The patient was intubated and placed on a cardiac monitor, and an external jugular venous central line was placed. Volume resuscitation with normal saline was initiated. The patient's abdomen became tense and distended, and he became pale. His heart rhythm deteriorated to ventricular fibrillation, and after unsuccessful resuscitation efforts, including defibrillation, the patient died.

Discussion

Aneurysms frequently present with subtle and non-specific signs, yet diagnosis of aneurysms is crucial because of the catastrophic complications that can occur. AAA rupture has a mortality rate of 81% (3), and interventions such as endovascular aneurysm repair or open surgery are performed to prevent rupture when the risk of rupture is significant (5).

The pathogenesis of AAA is a multifactorial process, with underlying genetic, inflammatory, and autoimmune components (7, 8). After an aneurysm has formed, many factors associated with greater risk of rupture have been identified including maximum diameter of the aneurysm, rate of increase in aneurysm size, hypertension, age, smoking history, COPD, bronchiectasis, and family history of aneurysms (9–11).

Among these factors, the maximum AAA diameter remains the most widespread criterion to predict risk of AAA rupture (5, 11). There is a direct relationship between the size of the aneurysm and risk of rupture, although size alone is not an adequate predictor. Other parameters, including AAA expansion rate, intraluminal thrombus thickness, and wall stress, all play a role (5). Even in asymptomatic unruptured aneurysms, repair of the aneurysm is indicated when the aneurysm exceeds 5.5 cm in size in patients with an acceptable surgical risk (1).

In recent years, ultrasound has become an increasingly useful modality for the initial detection and size measurement of AAA and has been shown to have a sensitivity of 98.9%, and a specificity of 99% (6, 12). For patients in whom AAA is suspected, ultrasound is the preferred initial imaging test and may be conducted at bedside (5, 6). Although ultrasound is useful for identifying aneurysms, it has limited ability to characterize features of impending rupture. In some cases, the usefulness of ultrasound may be limited by the patient's body habitus, or bowel gas may obscure visualization of the abdominal aorta (13).

Generally, CT with IV contrast is the preferred imaging modality when an AAA has been identified on ultrasound, or when the patient is experiencing severe symptoms, a pulsatile abdominal mass, or has significant risk factors for AAA (5). CT may reveal rupture, features of an impending rupture, or an alternative diagnosis for the patient's symptoms.

With the administration of IV contrast, aneurysms often reveal a patent lumen with thrombus lining the walls of the aneurysm. The mural thrombus is believed to be protective from rupture, and a thinner mural thrombus is associated with higher rupture risk (14). In cases of impending rupture, the contrast-enhanced blood may be seen penetrating into mural thrombus lining the aneurysm. This focal fissurization represents a tract of blood extruding into the unstable thrombus (10).

If blood transits beyond the mural thrombus, it may travel along the intimal margin of the aorta and perfuse the periphery of the organized thrombus (15). This produces the ‘hyperattenuating crescent’ sign, as shown in Fig. 1. The hyperattenuating crescent sign has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 93% for rupture, pseudoaneurysm, or intramural hematoma found at the time of surgery (16).

After extending through the mural thrombus, blood may begin to leak through the vessel wall. Small leaks can occur without frank rupture and exsanguination. Small aortic leaks may be seen as fluid or hematoma in the abdomen. Often, these collections are seen within the psoas muscle, or obscuring the anterior surface of the psoas (17).

In cases of impending rupture, prompt intervention is necessary. Emergent consultation with a vascular surgeon is required to establish a plan for definitive therapy. Blood pressure control is important for stabilization of unruptured aneurysms (5). In the event of aneurysm rupture, ‘hypotensive hemostasis’ has anecdotally been shown to improve patient outcomes (18). Although counterintuitive, physicians should consider deferring fluid resuscitation if the patient is conscious, and systolic pressure is at least 50–70 mmHg (19). Resuscitation with large fluid volumes may result in rapid exsanguination into the abdominal cavity. Larger transfusion volume requirements as well as large retroperitoneal hematomas have been associated with increased risk for abdominal compartment syndrome, characterized by intra-abdominal hypertension and multi-organ dysfunction (20).

Conclusion

AAA rupture is a critical event with a high mortality rate. A thorough knowledge of the risk factors and tomographic imaging features of impending rupture allow physicians to be prepared to respond decisively. Important risk factors for rupture include maximum diameter of the aneurysm, smoking history, and age. On CT scan, focal fissuring of thrombus, the hyperattenuating crescent sign, and small aortic leaks may signify an impending rupture and should prompt rapid surgical consultation. In cases of rupture, cardiopulmonary resuscitation and aggressive intervention may be required. Volume resuscitation is indicated only when the patient is unresponsive, or if systolic pressure is less than 70 mmHg.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of information, have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

References

- 1.Mussa FF. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62(3):774–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McPhee JT, Hill JS, Eslami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001–2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reimerink JJ, van der Laan MJ, Koelemay MJ, Balm R, Legemate DA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2013;100(11):1405–13. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LeFevre ML. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):281–90. doi: 10.7326/M14-1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaikof EL, Brewster DC, Dalman RL, Makaroun MS, Illig KA, Sicard GA, et al. The care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(Suppl 4):S2–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, Paladino L, Sinert R. Systematic review: Emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosis of suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(2):128–38. doi: 10.1111/acem.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dale MA, Ruhlman MK, Baxter BT. Inflammatory cell phenotypes in AAAs: Their role and potential as targets for therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35(8):1746–55. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuivaniemi H, Platsoucas CD, Tilson MD 3rd. Aortic aneurysms: An immune disease with a strong genetic component. Circulation. 2008;117(2):242–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.690982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun KC, Teng KY, Chavez LA, Van Spyk EN, Samadzadeh KM, Carson JG, et al. Risk factors associated with the diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients screened at a regional Veterans Affairs health care system. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28(1):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vu KN, Kaitoukov Y, Morin-Roy F, Kauffmann C, Giroux MF, Thérasse E, et al. Rupture signs on computed tomography, treatment, and outcome of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Insights Imaging. 2014;5(3):281–93. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0327-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan S, Verma V, Verma S, Polzer S, Jha S. Assessing the potential risk of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Clin Radiol. 2015;70:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindholt JS, Vammen S, Juul S, Henneberg EW, Fasting H. The validity of ultrasonographic scanning as screening method for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:472–5. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.1999.0835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffmann B, Bessman ES, Um P, Ding R, McCarthy ML. Successful sonographic visualisation of the abdominal aorta differs significantly among a diverse group of credentialed emergency department providers. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(6):472–6. doi: 10.1136/emj.2009.086462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rakita D, Newatia A, Hines JJ, Siegel DN, Friedman B. Spectrum of CT findings in rupture and impending rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Radiographics. 2007;27(2):497–507. doi: 10.1148/rg.272065026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonsalves C. The hyperattenuating crescent sign. Radiology. 1999;211(1):37–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.1.r99ap1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehard W, Heiken J, Sicard G. High-attenuating crescent in abdominal aortic aneurysm wall at CT: A sign of acute or impending rupture. Radiology. 1994;192(2):359–62. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.2.8029397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadgaonkar AD, Black JH, 3rd, Weihe EK, Zimmerman SL, Fishman EK, Johnson PT. Abdominal aortic aneurysms revisited: MDCT with multiplanar reconstructions for identifying indicators of instability in the pre- and posoperative patient. Radiographics. 2015;35(1):254–68. doi: 10.1148/rg.351130137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer D, Pfammatter T, Rancic Z, Hechelhammer L, Wilhelm M, Veith FJ, et al. 10 years of emergency endovascular aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortoiliac aneurysms: Lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2009;249(3):510–15. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31819a8b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veith FJ, Ohki T, Lipsitz EC, Suggs WD, Cynamon J. Endovascular grafts and other catheter-directed techniques in the management of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Semin Vasc Surg. 2003;16(4):326–31. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta M, Darling RC, 3rd, Roddy SP, Fecteau S, Ozsvath KJ, Kreienberg PB, et al. Factors associated with abdominal compartment syndrome complicating endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(6):1047–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]