Abstract

The general view that only adaptive immunity can build immunological memory has recently been challenged. In organisms lacking adaptive immunity as well as in mammals, the innate immune system can mount resistance to reinfection, a phenomenon termed trained immunity or innate immune memory. Trained immunity is orchestrated by epigenetic reprogramming, broadly defined as sustained changes in gene expression and cell physiology that do not involve permanent genetic changes such as mutations and recombination, which are essential for adaptive immunity. The discovery of trained immunity may open the door for novel vaccine approaches, for new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of immune deficiency states, and for modulation of exaggerated inflammation in autoinflammatory diseases.

Introduction

Host immune responses are classically divided into innate immune responses, which react rapidly and nonspecifically upon encountering a pathogen, and adaptive immune responses, which are slower to develop but are specific (due to antigen receptor gene rearrangements) and result in classical immunological memory. This schematic distinction has been challenged by the discovery of pattern recognition receptors that confer some specificity to the recognition of microorganisms by innate immune cells (1), and by a growing body of literature showing that the innate immune system can adapt its function after previous insults (2, 3). Protection against reinfection has been reported not only in plants and invertebrates that do not have adaptive immunity (4), but also in mammals, with old and new studies demonstrating cross-protection between infections with different pathogens (5). These studies have led to the hypothesis that innate immunity can be influenced by previous encounters with pathogens or their products, and this property has been termed trained immunity or innate immune memory.

Compared to classical immunological memory, trained immunity has a number of defining characteristics. Firstly, it involves a set of cells (myeloid cells, natural killer (NK) cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs)) and germline encoded recognition and effector molecules (e.g. pattern recognition receptors, cytokines) different from those involved in classical immunological memory. Secondly, and in contrast to classical immunological memory that depends of gene rearrangement and proliferation of antigen-specific lymphocyte clones, the increased responsiveness to secondary stimuli during trained immunity is not specific for a particular pathogen and it is mediated through signals impinging on transcription factors and epigenetic reprogramming. These are broadly defined as sustained changes in transcription programs through epigenetic rewiring, leading to changes in cell physiology that do not involve permanent genetic changes such as mutations and recombination. Finally, trained immunity relies on an altered functional state of innate immune cells that persists for weeks-to-months, rather than years, after the elimination of the initial stimulus.

In this context, it important to note that some innate immune cells such as NK-cells display both trained immunity characteristics as defined above, as well as antigen-dependent (or even antigen-specific) immunity that is related to the classical immunological memory mediated by T- and B-lymphocytes (see below for detailed description). In addition, it is important to clearly discriminate between trained immunity and other immunological processes such as immune cell activation and immune cell differentiation. During immune cell activation transcription of genes takes place at the time of stimulation in response to a ligand directly acting on the cell. In contrast, during trained immunity innate immune cells display gene- or locus-specific changes in their chromatin profiles induced by a previous stimulation. These changes, however, allow increasing response to restimulation of the cells through both the same and different PRRs.. The discrimination between trained immunity and immune cell differentiation is more difficult, and to a certain degree is even semantic: one could argue that macrophage differentiation could also be considered an example of trained immunity. However, immune cell differentiation can (and does) occur also during homeostatic conditions, while trained immunity is defined as a reaction to a foreign insult. In addition, while the term “circulating differentiated monocyte” could also be used instead of “trained monocyte”, we believe that this may be confusing, as monocyte differentiation is generally considered equivalent to the process through which blood monocytes differentiate into macrophages in the tissues. Moreover, differentiated cells such as macrophages can be trained as well (e.g. after infection or vaccination), and thus their capacity to display increased function should be defined differently than cell differentiation.

Defining the properties of trained immunity will critically integrate our understanding of host defense, and in this review we will describe the concept as well as discuss recent data that support its important role in health and disease. We will not review classical immunological memory, as this is the subject of many excellent reviews.

Immunological memory in plants and invertebrate animals

A first line of evidence that innate immune system has the capacity to build memory to previous insults comes from a plethora of immunological studies in plants. Collectively, they provide compelling evidence of the capacity to respond more efficiently to reinfection, a phenomenon termed Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) (6). The molecular mechanisms and biochemical mediators of SAR are largely known (6), with epigenetic-based rewiring of host defense playing a central role (7). In addition, there is increasing evidence to suggest that innate immunity displays memory traits, not only in plants, but also in invertebrate animals (4). For example the microbiota has been shown to induce innate immune memory to protect mosquitoes against Plasmodium (8); the social insect Bombus terrestris displays innate immune memory against three different pathogens (9), and the tapeworm Schistocephalus solidus induces memory in the copepod crustacean (10): in these models the organism is protected against re-encounter with the pathogen by an improved clearance of the infection. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that immunological memory is found not only in vertebrates, but also in plants and lower animals (3, 4).

Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for innate immune memory in invertebrates, including the sustained up-regulation of immune regulatory pathways such as the Toll and Imd receptors on the haematocytes (11) or of the bacterial peptidoglycan recognition molecules and lectins (12), and quantitative and phenotypic changes in immune cell populations (8). Alternatively, memory may be due to the presence of diversity-generating mechanisms in insects, such as generation of variation in fibrinogen-related proteins (likely acting as pathogen sensors) with high rates of diversification at the genomic level through point mutations and recombinatorial processes (13). The Toll-like receptors (TLRs), that are the animal counterpart of Toll in Drosophila, also show great diversity in the sea urchin, which have an estimated 222 receptors (14).

Innate immune memory in vertebrates

The presence of memory characteristics in innate host defense of different plant and animal lineages suggests that innate immune memory may also be present in vertebrates. Important clues that vertebrate innate immunity also has adaptive characteristics came from experimental studies in mice showing that priming (or training) of mice with microbial ligands of pattern recognition receptors can protect against a subsequent lethal infection. For example, trained immunity induced by β-glucan (a polysaccharide component of mainly fungal cell walls) induces protection against infection with Staphylococcus aureus (15, 16). Similarly, the peptidoglycan component muramyl dipeptide induces protection against Toxoplasma (17), and prophylactic treatment with TLR9 agonists such as oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG dinucleotides three days before the infection protects against sepsis and Escherichia coli meningitis (18). Furthermore, flagellin can induce protection against S. pneumonia (19) and rotavirus (20), the latter being independent of adaptive immunity and induced by dendritic cell-derived interleukin (IL)-18, which in turn drives production of IL-22 by epithelial cells. In addition to microbial ligands, there is evidence that certain proinflammatory cytokines may induce trained immunity: injection of mice with one dose of recombinant IL-1 three days before infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa protected the mice against mortality (21). The nonspecific character of the trained immunity argues against a classical immunological memory effect and suggests instead the activation of nonspecific innate immune mechanisms.

Compelling evidence that trained immunity is induced in vertebrates and mediates at least some of the protective effects of vaccination came from studies showing that immunization of mice with bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG, the tuberculosis vaccine that is also the most commonly used vaccine worldwide), induces T cell-independent protection against secondary infections with Candida albicans or Schistosoma mansoni (22, 23). The hypothesis that trained immunity can be elicited in vertebrates is further supported by studies investigating the mechanism of protection against disseminated candidiasis conferred by attenuated strains of C. albicans. For example, when an attenuated PCA-2 strain of C. albicans that is incapable of germination is injected in mice, protection is induced against the virulent strain CA-6 (24). Importantly, this protection was also induced in athymic mice and Rag1-deficient animals (that cannot rearrange their antigen receptors), demonstrating a lymphocyte-independent mechanism (25, 26). The protection against reinfection was instead dependent on macrophages (24) and proinflammatory cytokine production (27), both prototypical innate immune components.

In addition to BCG and C. albicans, some viral and parasitic organisms can exert protective effects through mechanisms independent of adaptive immunity. Herpes virus latency increases resistance to the bacterial pathogens Listeria monocytogenes and Yersinia pestis (28), with protection achieved through enhanced production of the cytokine interferon (IFN)γ and systemic activation of macrophages. Similarly, infection with the helminth parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis induces a long-term macrophage phenotype that on the one hand damages the parasite and on the other induces T and B lymphocyte-independent protection from reinfection (29).

Other studies have shown that natural killer (NK) cells also display immune memory. This was first demonstrated in mice that showed hapten-induced contact hypersensitivity dependent on NK-cells that persisted for at least 4 weeks (30). Consistent with this notion, several subsequent studies reported that infection with murine cytomegalovirus (mCMV) induces immunological memory independent of T- and B-cells (31-34). The protection in these models is mediated by NK-cells, which proliferate and persist in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs. Upon reinfection, these “memory” NK cells undergo a secondary expansion, rapidly degranulating and releasing cytokines, thus inducing a protective immune response (31). Interestingly, it has also been shown that NK cells can prime monocytes in the bone marrow during infection, and this may also induce long-term effects on innate immune responses (35).

In addition to experimental studies showing induction of innate immune memory in mice, emerging data suggest that similar trained immunity effects can be generated in humans. Firstly, a large number of epidemiological studies have shown nonspecific beneficial effects of live vaccines such as BCG, measles vaccines, and oral polio vaccine against infections other than the target diseases (36). The identification of these nonspecific (or heterologous) effects suggests that these vaccines induce trained immunity that protects against unrelated pathogens. This hypothesis was proposed in proof-of-principle trials with BCG vaccine in healthy adult volunteers (37), and thereafter validated in clinical trials in newborn children vaccinated with BCG (38) or exposed in utero to hepatitis B vaccine (39). Secondly, certain infections such as malaria can also induce a state of hyper-responsiveness that is functionally equivalent to the induction of trained immunity (40, 41). Finally, non-specific protective effects through innate immunity-dependent mechanisms are provided by the use of BCG for treatment of malignancies such as bladder cancer (42), melanoma (43), leukemia (44), and lymphoma (45): although direct inflammatory effects are likely important, long-term innate immune memory persisting between the BCG treatments is also likely involved. In this respect, it has been recently suggested that these anti-cancer effects of BCG are directly dependent on the capacity to mount trained immunity, as individuals unable to mount trained immunity due to autophagy defects show a diminished recurrence-free survival after BCG treatment in bladder carcinoma (46).

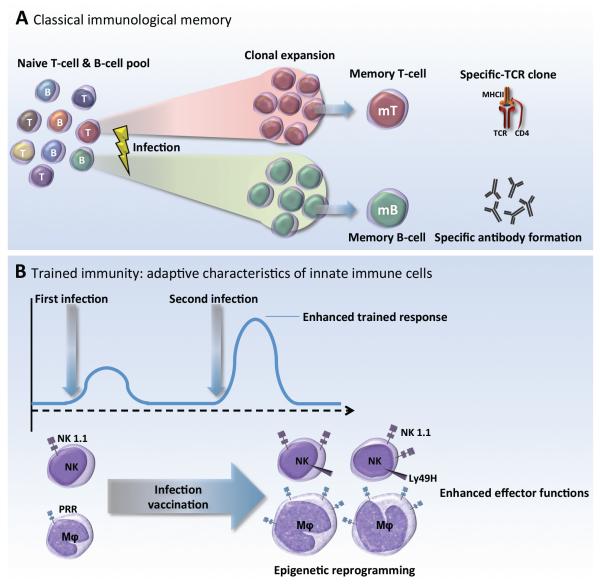

Taken together, these complementary murine and human studies suggest that innate immune responses have the capacity to be “primed” or “trained,” and thereby exert a new type of immunological memory upon re-infection, for which the term trained immunity has been proposed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A. Classical adaptive immunological memory involves gene recombination in B- and T-lymphocytes, which confers high specificity and very often long-term, pathogen-specific protection (up to decades). B. Trained immunity defines a de-facto innate immune memory that induces enhanced inflammatory and antimicrobial properties in innate immune cells, responsible for an increased non-specific response to subsequent infections and improved survival of the host.

Mechanisms responsible for mediating trained immunity

Innate immune cells that build innate immune memory

Innate immune memory properties have been described in several cell populations including monocytes/macrophages and NK cells, while preliminary observations suggest that similar characteristics may also be present in other cell types such as innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) or polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Unlike lymphocytes, innate immune cells do not express rearranging antigen receptor genes, but they do express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) and other receptors that allow them to recognize and respond to pathogen-derived structures (pathogen-associated molecular patterns, PAMPs) and endogenous danger signals (damage-associated molecular patterns, DAMPs) (47, 48). Although these responses are not specific to the degree conferred by antigen receptors, there is evidence that expression of distinct members of pattern recognition receptor families (e.g., Toll-like receptors, NOD-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors, RIG-I-like receptors, or combinations thereof) on macrophages and dendritic cells does indeed trigger different signaling pathways that lead to innate immune responses that are tailored on the type of pathogen encountered (49).

Among the various cell types implicated in innate immune memory, the major focus has been on monocytes/macrophages and NK cells. We note that this attention does not necessarily mean that these cells are more amenable to training than other innate immune cells (or conceivably other somatic cell types). Instead, this focus may merely reflect historical connection of these cells with lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced tolerance (LPS is a component of Gram-negative bacterial cell walls). Indeed, some of the first evidence that macrophages may exhibit memory-like features came from investigations of LPS-induced tolerance at the molecular level (50). In one such study, gene-specific chromatin modifications were associated with silencing of genes coding for inflammatory molecules, while priming other genes coding for antimicrobial molecules (50). These findings suggested that macrophages could be primed by LPS to become more or less responsive to subsequent activation signals. This observation was expanded by studies that demonstrated that exposure of monocytes/macrophages to C. albicans or β-glucan enhanced their subsequent response to stimulation with unrelated pathogens or PAMPs, process termed as trained immunity (26). Training was demonstrated to be accompanied by significant reprogramming of chromatin marks (26, 51) (50), as detailed further below. Besides bacterial and fungal pathogens, monocytes/macrophages can also mount trained immunity responses following infection with parasitic (29) and viral (28) pathogens.

An important aspect to be considered regarding trained immunity in monocytes is the lifespan of these cells. Monocytes are cells with a short half-life in circulation, with recent studies suggesting it to be up to one day (52). The observation that trained monocytes have been identified in the circulation of BCG-vaccinated individuals for at least three months after vaccination (37) suggests that reprogramming must take place at the level of progenitor cells in the bone marrow as well. Indeed, recent evidence has emerged that innate immune memory can be transferred via hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Macrophages derived from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells rendered tolerant by TLR2 ligand exposure and transferred to irradiated mice retain a tolerant phenotype and produce lower amounts of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species in response to inflammatory stimulation (53). Furthermore, exposure of the skin of mice to UV radiation induces immunosuppression that was originally attributed to defective T-cell priming by dendritic cells (54), but was subsequently shown to involve epigenetic reprogramming and a long-lasting effect on dendritic cell progenitors in the bone marrow that altered the function of their differentiated progeny (55). In addition, recent studies have suggested that microbiota can induce long-term functional reprogramming of bone marrow progenitors, and subsequently dendritic cells, to induce protection against Entamoeba histolytica (56). Whether vaccines know to induce trained immunity, such as BCG, can also confer or induce similar effects at the level of progenitor cells remains to be established.

Emerging evidence suggests that NK cells also respond more vigorously after a previous challenge. NK cell memory has been documented following exposure to cytokine combinations (e.g., IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18) (32) or hapten sensitization, which induced long-lived NK cells that mediate contact hypersensitivity and long-lived antigen-specific recall responses independently of B and T cells (30). In addition, NK cells undergo expansion during virus infections such as those with murine CMV (31), influenza A (57), or vaccinia virus (58). Studies of CMV infection have shown that NK cell activation may provide T cell-independent protection against reinfection by rapidly degranulating and producing cytokines (31). Furthermore, adoptive transfer experiments have demonstrated that activated NK cells can proliferate in vivo and protect naïve recipient mice against virus infection, suggesting that they could confer protective immunological memory. The nonspecific protective effects of BCG infection have also been linked with activation of NK cells. NK cells from BCG-vaccinated individuals have enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in response to mycobacteria and other unrelated pathogens, and studies in mice have shown that BCG confers nonspecific protection against C. albicans at least partially through NK-cells (59).

A number of mechanisms have been put forward that may mediate the memory properties of NK cells: some of them are responsible for induction of innate immune memory, and others for the survival of the NK memory cells. The former include enhanced responsiveness of the IL-12/IFNγ axis (32) or the activation of the co-stimulatory molecule DNAM-1 (DNAX accessory molecule-1, CD226) on the membrane of the cells (60), while survival of the memory NK cells during the contraction phase after murine CMV infection necessitates mitophagy through an Atg3-dependent mechanism (61). The issue of specificity of the NK memory immune responses is complex. Evidence that NK memory is specific was provided by the demonstration that in the mouse mCMV-induced NK cells protected against mCMV but not Epstein-Barr virus, another herpesvirus (62). Interestingly, mCMV impaired heterologous immunity against influenza and L. monocytogenes (57, 63). Memory responses of NK cells towards other stimuli such as haptens and viruses also induced antigen-specific immune memory (41). Another important aspect concerns the mechanisms responsible for the persistence of NK memory cells. NK cell memory of haptens and viruses depends on CXCR6, a chemokine receptor on hepatic NK cells that is required for the persistence of memory NK cells but not for antigen recognition (41). In addition, recent studies revealed evidence of NK memory in primates: splenic and hepatic NK cells from Adenovirus 26-vaccinated macaques efficiently lysed antigen-matched but not antigen-mismatched targets five years after vaccination. These data demonstrate that robust, durable, antigen-specific NK cell memory can be induced in primates after both infection and vaccination. This finding has important implications for the development of vaccines against HIV-1 and other pathogens (64).

In addition to studies showing antigen-specific mechanisms of NK cell immune memory, other recent studies have suggested that memory in NK cells is also mediated by epigenetic changes. In a study in patients recovering from CMV virus infection, the DNA methylation patterns of NK-cells and cytotoxic T-cells were similar, and very different from those of canonical NK cells. Subsequently, the capacity of these adaptive NK cells to secrete cytokines was modulated and this was dependent on the transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger (PLZF) (34, 65) Similarly, another study showed that these “memory-like NK cells” are defective in the Syk-dependent stimulation pathway, which is correlated with epigenetic changes at the level of the gene promoter (60).

Taken together, the published data suggest that NK immune memory is complex and may display aspects of both antigen-dependent (and in certain circumstances antigen-specific) memory, as well as epigenetic reprogramming as seen in trained immunity.

The molecular basis of trained immunity: transcriptional and epigenetic reprogramming

A distinguishing feature of the trained innate immune cell is its ability to mount a qualitatively different – and to some extent quantitatively stronger – transcriptional response compared to untrained cells when challenged with pathogen or danger signals. The molecular bases of such enhanced activation of a subset of inflammatory genes are only partially defined, but evidence supports the convergence of multiple regulatory layers, including changes in chromatin organization and the persistence of microRNAs (miRNAs) induced by the primary stimulus.

In myeloid cells, many loci encoding inflammatory genes are in a repressed configuration (66-68), as inferred by their limited accessibility to nucleases (used as tools to probe chromatin structure), the low acetylation of the nucleosomal histones, and the very low amount of RNA polymerase II loaded onto both the coding body of the genes and the genomic regulatory elements (enhancers and promoters) that control their expression (69). Upon primary stimulation, the changes observed at these loci, in terms of gain in chromatin accessibility, increased histone acetylation and RNA polymerase II recruitment, are massive and of magnitudes that are uncommonly observed in other responses to micro-environmental changes. These significant alterations, which in some cases result in the activation of gene expression hundreds of times higher than baseline in a short window of time, are driven by the recruitment of stimulation-responsive transcription factors (e.g., NF-κB, AP-1, and STAT family members) to enhancers and gene promoters, which are usually pre-marked by lineage-determining transcription factors such as PU.1 (70-73). In turn, transcription factors control the recruitment of coactivators (including histone acetyltransferases and chromatin remodelers) (67, 68) that locally modify chromatin to make it more accessible to transcriptional machinery.

Maintenance of such enhanced accessibility may underlie the more efficient induction of genes primed by the initial stimulation (50). Moreover, since histone modifications are specifically bound by recognition domains contained in various proteins implicated in transcriptional control (as in the case of the bromodomain-acetyl lysine interaction) (74), the persistence of histone modifications deposited at promoters or enhancers after the initial stimulus may itself impact the secondary response (26). The possible contribution of chromatin modifications to trained immunity must be examined taking into account the different stability of individual covalent chromatin modifications, with more stable modifications (e.g., histone methylation) being potentially more suitable to perpetuate a functional change than those with a typically short half-life (e.g., histone acetylation). Therefore, the observed long-term persistence of some histone modifications in myeloid cells after removal of the initial activation stimulus may reflect either their stability or, alternatively, the sustained activation of the upstream signaling pathways and transcription factors that control their deposition.

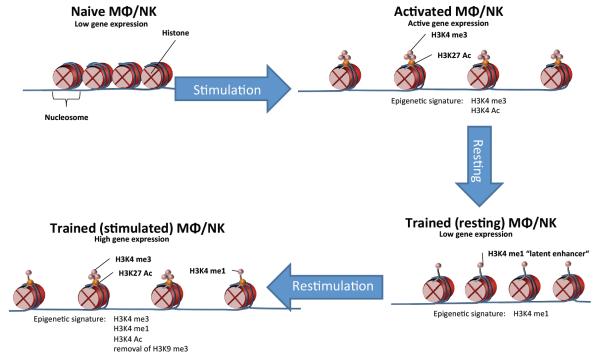

One interesting paradigm is provided by latent or de novo enhancers (75, 76), which are genomic regulatory elements that are epigenetically unmarked or marked at low levels in unstimulated cells but gain histone modifications characteristic of enhancers (such as monomethylation of histone H3 at K4, H3K4me1) only in response to specific stimuli. In vitro, upon removal of the stimulus that triggered their functionalization, a fraction of latent enhancers retain their modified histones and can undergo a stronger activation in response to restimulation (Figure 2). This observation is reminiscent of the fact that in vivo macrophages acquire repertoires of active enhancers that are largely instructed by the micro-environmental signals specific to a given tissue, and are thus to a large extent different depending on the organ in which a macrophage is located (77, 78). In turn, such signals act by specifically inducing regulation by distinct combinations of transcription factors eventually responsible for the activation of different sets of genes mediated by epigenetic modifying enzymes. Transferring macrophages from one tissue to another results in an extensive reprogramming of the enhancer repertoire (78). Therefore, a complex equilibrium exists between mechanisms that promote the persistence of the modified epigenome instructed by the previously encountered stimuli, and mechanisms that reprogram it in response to a changing environment. The very same dynamic equilibrium likely underlies the persistence of chromatin states that are relevant to enhanced transcriptional responses in trained immunity.

Figure 2.

Epigenetic rewiring underlies the adaptive characteristics of innate immune cells during trained immunity. Initial activation of gene transcription is accompanied by the acquisition of specific chromatin marks, which are only partially lost after elimination of the stimulus. The enhanced epigenetic status of the innate immune cells, illustrated by the persistence of histone marks such as H3K4me1 characterizing ‘latent enhancers’, results in a stronger response to secondary stimuli upon re-challenge.

Recent studies have investigated the changes in epigenomic programs in innate immune cells during induction of trained immunity. One early study proposed that changes in epigenetic status underlie the repression of inflammatory genes during LPS tolerance, however genes mainly involved in antimicrobial responses were either normally produced or even displayed an increased production capacity (50). The repression of inflammatory mediators production and the potentiation of antimicrobial proteins synthesis were accompanied by histone repressive or activating marks, respectively. Similarly, exposure of monocytes/macrophages to C. albicans or β-glucan modulated their subsequent response to stimulation with unrelated pathogens or PAMPs, and the changed functional landscape of the trained monocytes was accompanied by epigenetic reprogramming (26, 51). Pathway analysis identified important immunological (cAMP-PKA activation) and metabolic (aerobic glycolysis) pathways that play crucial roles in induction of trained immunity (51, 79). In addition, a recent study showed that both LPS and β–glucan induce trained immunity through a MAPK-dependent pathway that phosphorylates the transcription factor ATF7, subsequently reducing the repressive histone mark H3K9me2 (80). Moreover, the immunological networks activated in trained monocytes depend on STAT1 activation (80), and the importance of STAT1 for the induction of trained immunity is supported by the defects in trained immunity reported in patients with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis due to STAT1 mutations (81).

BCG vaccination has also been shown to result in an increase in inflammatory mediators produced by monocytes from healthy volunteers, which correlated with parallel changes in a histone modification associated with gene activation (37). Similarly to monocytes and macrophages, the induction of CMV-induced NK cell memory at least partially relies on epigenetic reprogramming, which is linked to reduced expression of PLZF (34) and the tyrosine kinase SYK (65). Finally, human CMV also drives epigenetic priming of the IFNG locus in NK cells, which ‘tags’ the gene and leads to consistent IFNγ production in a subset of NK cells, providing a molecular basis for the adaptive feature of these cells (82). Finally, we note that the epigenetic machinery of the immune system may also be hijacked by certain bacterial pathogens such as L. monocytogenes (83), and this may represent a more general escape mechanism from host defense (84, 85).

miRNAs may also contribute to trained immunity (86), mainly because of the reportedly long half-life of these molecules (87) that, combined with the limited proliferative ability of myeloid cells, would result in their persistence after removal of the primary stimulus. Among miRNAs, miR-155 may have particular relevance because its up-regulation in response to inflammatory signals such as microbial components is associated with the hyperactivation of myeloid cells, possibly due to the derepression of phosphatases that negatively regulate transducers of several signaling pathways (88). It can be predicted that myeloid cells expressing miR-155 in a sustained manner would remain in a primed, hyper-sensitive state: upon exposure to a secondary stimulus of identical strength, they would be able to respond in an enhanced manner compared to the primary stimulation.

While the discussion above addresses the role of epigenetic programing as a mechanism for mediating innate immune memory, one crucial aspect remains open: what cellular processes induce and maintain these epigenetic changes? There is increasing evidence to suggest that rewiring of cellular metabolism is involved, with a role for metabolites as cofactors for enzymes involved in epigenetic modulation of gene transcription.

Immunometabolic circuits: the role of cellular metabolites for shaping the epigenetic program of trained innate immune cells

Recent work revealed extensive rewiring of metabolic pathways in different immune cells upon activation (89). The best example concerns macrophages, where the M1 phenotype (i.e., macrophages activated with LPS and IFNγ, producing mainly inflammatory cytokines) and M2 phenotype (macrophages activated by IL-4-related cytokines and expressing genes involved in tissue repair) use distinct metabolic pathways (90, 91). M1 macrophages are largely glycolytic, with impairment of oxidative phosphorylation and disruption of the Krebs cycle at two steps, after citrate and after succinate. Citrate is withdrawn for fatty acid biosynthesis (which enables the increased production of inflammatory prostaglandins), whereas succinate activates the transcription factor HIF1α, which regulates a wide range of genes, including the one encoding the inflammatory mediator IL-1β (90, 91). In M2 macrophages, the Krebs cycle is intact; a key feature is the synthesis of uridine diphosphate N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) from glucose and glutamine, which is needed for the extensive glycosylation occurring in receptors such as mannose-binding lectin, which are hallmarks of the M2 phenotype (91).

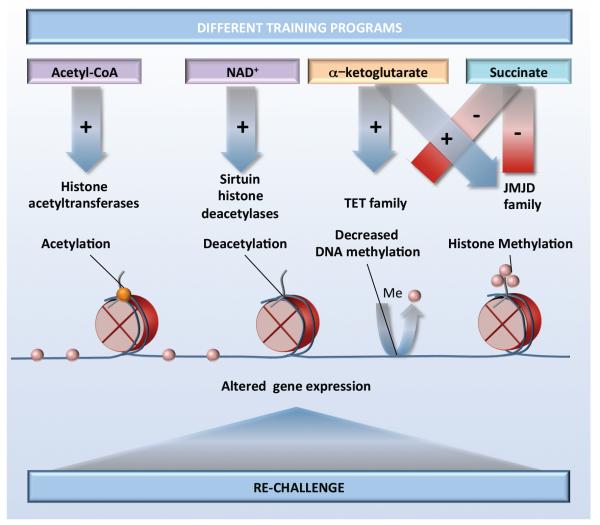

The importance of cellular metabolism for macrophage programming suggests that similar mechanisms may play a role for the long-term functional changes in monocytes and macrophages during trained immunity. In line with this, an important role for a shift from oxidative phosphorylation towards glycolysis through an Akt/mTOR/HIF-1α-dependent pathway has been recently reported to be essential for trained immunity induced by β–glucan (51, 79). Whether and how this shift influences epigenetic processes in trained immunity is still under investigation, but important clues have been given by studies linking chromatin regulation to intermediary metabolism (for reviews see (92, 93). In this respect, a critical metabolic intermediate that is increased in trained monocytes, acetyl-CoA, is required for histone acetylation. In addition, the ratio of the TCA cycle metabolites α-ketoglutarate and succinate is a critical determinant for the activity of two families of enzymes controlling epigenetic modifications, the JMJ (Jumonji domain-containing) family of lysine demethylases and the TET (ten-eleven translocation) family of methyl-cytosine hydroxylases (51, 94). These enzymes require α-ketoglutarate as a cofactor, whereas succinate limits their activity (Figure 3). An additional possibility for innate immune memory may be that stimulation of macrophages causes an elevation in succinate; this would then inhibit JMJD3, leading to enhanced H3K27 trimethylation of particular genes (e.g., those associated with the M2 phenotype), suppressing their expression (95). This process would maintain a proinflammatory phenotype of trained macrophages upon restimulation. Important links between altered metabolites and epigenetic changes have been also demonstrated in LPS-induced tolerance, in which NAD+-dependent activation of class III histone deacetylases (sirtuins) functions with sirtuin-1 and sirtuin-6 in coordinating a switch from glucose to fatty acid oxidation (96). The challenges to the field are on the one hand to explain how these potentially non-specific functions of metabolites could have locus/gene-specific effects, and on the other hand to provide direct evidence for metabolites altering the activity of enzymes that modify DNA and histones during trained immunity.

Figure 3.

Stimulation of innate immune cells with training stimuli induces changes in cellular metabolism. Various metabolites function as co-factors for epigenetic enzymes, which in turn induce chromatin and DNA modifications, modulate gene transcription and result in different trained immunity programs.

Adaptive and maladaptive programs

As described above, trained immunity most likely evolved as a primitive form of immune memory, aimed to provide improved protection of the host against reinfection, with beneficial effects for survival. It is also likely that trained immunity plays an important role in ontogeny, enabling the maturation of the innate immune system of the newborn (97), a process in which microbiota plays an important role (98). In line with the notion that microbiota might influence the functional program of immune cells, a recent study showed increased H3K4me3 in NK cells from conventionally housed mice compared with germ-free animals (99). However, there may also be situations in which reprogramming of innate immunity and increased inflammatory responses to exogenous or endogenous stimuli may also have deleterious effects.

Several pathological conditions have been described in which innate immune reprogramming may have deleterious effects. During LPS-induced tolerance, reprogramming of innate immune cells likely plays a beneficial role in maintaining a relatively high threshold of cellular activation in organs in which LPS naturally occurs at physiological levels, such as in the gastrointestinal tract (50). In contrast, in the case of systemic activation of innate immune cells during sepsis, LPS-induced tolerance can contribute to immune paralysis, placing the individual at greater risk for opportunistic infections (100). Persistent silencing of important host defense genes, possibly due to epigenetic mechanisms, has been proposed to mediate these effects (101, 102). Hence, maladaptive responses that inappropriately affect cell populations such as systemic monocytes, as opposed to local tissue-resident macrophages, can have detrimental effects for the host.

There are also examples of deleterious systemic consequences of trained immunity. In general, trained immunity is an adaptive response resulting in the long-lasting capacity to respond more strongly to stimuli (36). While this type of high-alert immune state has beneficial effects during host defense, it could also trigger enhanced tissue damage during chronic inflammatory conditions in which trained immunity is induced by endogenous ligands of innate receptors. For example, there is strong epidemiological evidence for an increased susceptibility of atherosclerosis in patients with autoimmunity or chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (103). It is tempting to speculate that the maladaptive state of innate immune cells triggered by the underlying chronic inflammatory condition would change the local immune responsiveness of immune cells in atherosclerotic lesions and that this could contribute to the increased disease risk (104). It is also possible that Western-type diets, which are known to trigger systemic inflammatory responses, can precipitate maladaptive trained immune responses. A strong argument for this hypothesis is the recent demonstration of trained immunity induced by oxidized LDL in human monocytes via epigenetic reprogramming (105). Furthermore, this type of maladaptation of innate immune cells could be a culprit for other common inflammatory diseases prevalent in Western societies such as type 2 diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease. In diabetes, a bout of hyperglycemia can result in long-term deleterious effects, a process termed “hyperglycemic memory”: this condition is accompanied by sustained NF-κB activation by increased H3K4me1 and decreased H3K9me3 at selected genes (106).

The data presented above argue that the adaptive ability of innate immune cells to tune their responses to changing environments appears to be an important feature that evolved to prepare innate immune cells for unpredictable events, such as invading pathogens. However, the epigenetic mechanisms that control the memory of the environmental trigger may also lead to persistence of disease-associated phenotypes. Hence, altering the changed epigenetic landscape by pharmacologic means or behavioral changes could be a promising strategy to restore homeostatic healthy gene expression patterns.

Trained immunity: a modified steady-state of innate immunity after infection

In this review, we reappraised the various arguments pointing to the presence of innate immune memory in plants, lower animals as well as in vertebrates. We defined trained immunity as a non-specific immunological memory resulting from rewiring the epigenetic program and the functional state of the innate immune system, eventually resulting in protection against secondary infections. We also compared data assessing the mechanisms of tolerance and trained immunity. However, one important question remains: are tolerance and training two fundamentally opposing functional programs, or do they represent different facets of the same phenomenon?

When one considers the traditional appraisal of the effects of tolerance as a hypo-inflammatory state, and trained immunity resulting in an increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, these two programs may seem to be functional opposites. However, one needs to consider the evidence carefully: whole-genome transcriptional and epigenetic analysis has clearly demonstrated that while in the process of LPS-induced tolerance many proinflammatory genes are downregulated, others are not modified or even upregulated (50). Similarly, the assessment of the trained immunity program induced by β-glucans also shows that it contains both up- and down-regulated genes (51). It thus becomes evident that both tolerance and training represent manifestations of long-term epigenetic reprogramming of the innate immune system after encountering an infection or a microbial ligand.

A crucial aspect of trained immunity that needs further investigation is its duration. Invitro studies have demonstrated long-term memory effects in monocytes and macrophages lasting days (26, 75), while experimental studies reported effects that extended to weeks (26, 107). Epidemiological studies on the non-specific effects of vaccines such as BCG or measles have suggested positive effects on susceptibility to infections lasting for months and even years (36), although it is highly unlikely for this protection to be as long-lived as classical immunological memory. These data are supported by proof-of-principle studies demonstrating the presence of trained immunity effects on circulating monocytes of volunteers for three months and even one year after vaccination with BCG (108). This would imply effects of vaccination on bone marrow progenitors as well, as pointed out earlier. More studies are warranted to describe in more detail the duration of trained immunity effects after infection and vaccination.

Conclusions and future directions for research

The arguments presented above suggest that trained immunity is a fundamental property of host defense in mammalian immune response. Whereas classical immunological memory mediated by T and B lymphocytes is specific and antigen-dependent, with antigen specificity being mediated by gene rearrangement in specific lymphocyte clones that undergo expansion and contraction, trained immunity (innate immune memory) is non-specific and mediated through epigenetic reprogramming in myeloid cells or NK-cells. An important difference between classical immunological memory and trained immunity also concerns the persistence of the effects: memory within trained immunity has a shorter duration than classical adaptive immune memory.

Much remains to be learned in this exciting new field of immunology in the coming years. Firstly, the molecular mechanisms that mediate trained immunity should be elucidated at the level of the cell types involved, and the immunological, metabolic and epigenetic processes mediating it need to be unraveled further. It will be also important to delineate the duration of innate immune memory and the impact on the innate immune cell precursors in the bone marrow and tissue macrophage populations. Secondly, the fast progress of cutting edge technologies such as single cell transcriptomics and epigenomics, in particular DNA methylation, will permit the identification of the potential novel subpopulations of cells that are prone to display innate immune memory characteristics. This will enhance our understanding of immunological processes and open up possibilities for new therapeutics that target specific cell subpopulations. Thirdly, future research should explore the impact of trained immunity on disease: on the one hand, its role in diseases with impaired host defense such as post-sepsis immune paralysis or cancers, and on the other hand, its role in autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases in which maladaptive programs may be in place.

Finally, the concept of innate immune memory has considerable potential in helping the design of novel therapeutic approaches, with at least three potential lines of investigation: (1) the design of new generation vaccines that combine adaptive and innate immune memory, as recently proposed with a novel Bordetella pertussis vaccine (109); (2) the use of inducers of trained immunity for the treatment of immune paralysis, such as the muramyl dipeptide preparation mufamurtide for osteosarcoma (110) or beta-glucan in various cancer types (111); and (3) the modulation of the potentially deleterious consequences of trained immunity in autoinflammatory diseases (e.g. the potential use of the recently described iBET inhibitors). Only when this is accomplished will the full potential of the discovery of trained immunity be achieved.

Table 1.

Overview of innate immune memory mechanisms described for various types of innate immune cells.

| Innate immune cell type |

Primary challenge | Type of memory | Pathway involved | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monocytes - macrophages |

LPS | tolerance / trained immunity |

TLR4/MAPK-dependent ATF7-dependent |

Epigenetic changes: latent enhancers (H3K4me1), other modifications (H3K4me3, H2K27me, H3K9me2) |

Foster & Medzhitov (50) Ostuni et al (74) Yoshida et al (79) |

| Monocytes - macrophages |

β-glucan, Candida infection |

trained immunity | Dectin-1/Raf1/Akt-dependent STAT1-dependent |

Epigenetic changes (H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H2K27Ac, H3K9me2), metabolic rewiring |

Quintin et al (26) Saeed et al (51) Cheng et al (78) Yoshida et al (79) |

| NK-cells | Hapten-induced Influenza A Vaccinia virus HIV-1 infection |

antigen-specific | CXCR6-dependent NKG2D-dependent |

O’Leary et al (30) Paust et al. (57) Gillard et al (58) Reeves et al (63) |

|

| NK-cells | CMV infection | antigen-dependent | Atg3-mediated mitophagy | BNIP3-/BNIP3L-dependent | Sun et al (31) O’Sullivan et al (59) |

| NK-cells | CMV infection | trained immunity | Stable downregulation of adaptors and transcription factors (e.g. Syk, PLZF) |

Epigenetic modification of gene promotors DNA methylation |

Lee et al (64) Schlums et al (34) |

Acknowledgements

M.G.N. was supported by a Vici grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, and an ERC Consolidator Grant (#310372). E.L. is supported the grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Excellence Cluster ImmunoSensation and an ERC Consolidator Grant. G.N. work on this topic was supported by an ERC grant (NORM). K.H.G.M. is supported by a PI grant from Science Foundation Ireland (#11/P1/1036). We thank Mark Gresnigt for the help with the figures. The authors apologize to authors of studies that could not be cited due to space constraints.

References

- 1.Medzhitov R, Janeway C., Jr. Innate immune recognition: mechanisms and pathways. Immunol Rev. 2000 Feb;173:89. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowdish DM, Loffredo MS, Mukhopadhyay S, Mantovani A, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors implicated in the "adaptive" form of innate immunity. Microbes Infect. 2007 Nov-Dec;9:1680. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Netea MG, Quintin J, van der Meer JW. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011 May 19;9:355. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtz J. Specific memory within innate immune systems. Trends Immunol. 2005 Apr;26:186. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quintin J, Cheng SC, van der Meer JW, Netea MG. Innate immune memory: towards a better understanding of host defense mechanisms. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014 Aug;29:1. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kachroo A, Robin GP. Systemic signaling during plant defense. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2013 Aug;16:527. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luna E, Ton J. The epigenetic machinery controlling transgenerational systemic acquired resistance. Plant Signal Behav. 2012 Jun;7:615. doi: 10.4161/psb.20155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010 Sep 10;329:1353. doi: 10.1126/science.1190689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadd BM, Schmid-Hempel P. Insect immunity shows specificity in protection upon secondary pathogen exposure. Curr Biol. 2006 Jun 20;16:1206. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurtz J, Franz K. Innate defence: evidence for memory in invertebrate immunity. Nature. 2003 Sep 4;425:37. doi: 10.1038/425037a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutros M, Agaisse H, Perrimon N. Sequential activation of signaling pathways during innate immune responses in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2002 Nov;3:711. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner H. Peptidoglycan recognition proteins: on and off switches for innate immunity. Immunol Rev. 2004 Apr;198:83. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SM, Adema CM, Kepler TB, Loker ES. Diversification of Ig superfamily genes in an invertebrate. Science. 2004 Jul 9;305:251. doi: 10.1126/science.1088069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibino T, et al. The immune gene repertoire encoded in the purple sea urchin genome. Dev Biol. 2006 Dec 1;300:349. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Luzio NR, Williams DL. Protective effect of glucan against systemic Staphylococcus aureus septicemia in normal and leukemic mice. Infect Immun. 1978 Jun;20:804. doi: 10.1128/iai.20.3.804-810.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marakalala MJ, et al. Dectin-1 plays a redundant role in the immunomodulatory activities of beta-glucan-rich ligands in vivo. Microbes Infect. 2013 Jun;15:511. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krahenbuhl JL, Sharma SD, Ferraresi RW, Remington JS. Effects of muramyl dipeptide treatment on resistance to infection with Toxoplasma gondii in mice. Infect Immun. 1981 Feb;31:716. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.716-722.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribes S, et al. Intraperitoneal prophylaxis with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides protects neutropenic mice against intracerebral Escherichia coli K1 infection. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munoz N, et al. Mucosal administration of flagellin protects mice from Streptococcus pneumoniae lung infection. InfectImmun. 2010 Oct;78:4226. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00224-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang B, et al. Viral infection. Prevention and cure of rotavirus infection via TLR5/NLRC4-mediated production of IL-22 and IL-18. Science. 2014 Nov 14;346:861. doi: 10.1126/science.1256999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Meer JW, Barza M, Wolff SM, Dinarello CA. A low dose of recombinant interleukin 1 protects granulocytopenic mice from lethal gram-negative infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Mar;85:1620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van 't Wout JW, Poell R, van Furth R. The role of BCG/PPD-activated macrophages in resistance against systemic candidiasis in mice. Scand J Immunol. 1992 Nov;36:713. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1992.tb03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tribouley J, Tribouley-Duret J, Appriou M. [Effect of Bacillus Callmette Guerin (BCG) on the receptivity of nude mice to Schistosoma mansoni] C R Seances Soc Biol Fil. 1978;172:902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bistoni F, et al. Evidence for macrophage-mediated protection against lethal Candida albicans infection. Infect Immun. 1986 Feb;51:668. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.2.668-674.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bistoni F, et al. Immunomodulation by a low-virulence, agerminative variant of Candida albicans. Further evidence for macrophage activation as one of the effector mechanisms of nonspecific anti-infectious protection. J Med Vet Mycol. 1988;26:285. doi: 10.1080/02681218880000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quintin J, et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2012 Aug 16;12:223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vecchiarelli A, et al. Protective immunity induced by low-virulence Candida albicans: cytokine production in the development of the anti-infectious state. Cell Immunol. 1989 Dec;124:334. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(89)90135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton ES, et al. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature. 2007 May 17;447:326. doi: 10.1038/nature05762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen F, et al. Neutrophils prime a long-lived effector macrophage phenotype that mediates accelerated helminth expulsion. Nat Immunol. 2014 Oct;15:938. doi: 10.1038/ni.2984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Leary JG, Goodarzi M, Drayton DL, von Andrian UH. T cell- and B cell-independent adaptive immunity mediated by natural killer cells. Nat Immunol. 2006 May;7:507. doi: 10.1038/ni1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature. 2009 Jan 29;457:557. doi: 10.1038/nature07665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun JC, et al. Proinflammatory cytokine signaling required for the generation of natural killer cell memory. J Exp Med. 2012 May 7;209:947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nabekura T, Girard JP, Lanier LL. IL-33 Receptor ST2 Amplifies the Expansion of NK Cells and Enhances Host Defense during Mouse Cytomegalovirus Infection. J Immunol. 2015 Jun 15;194:5948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlums H, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection drives adaptive epigenetic diversification of NK cells with altered signaling and effector function. Immunity. 2015 Mar 17;42:443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Askenase MH, et al. Bone-Marrow-Resident NK Cells Prime Monocytes for Regulatory Function during Infection. Immunity. 2015 Jun 16;42:1130. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Benn CS, Netea MG, Selin LK, Aaby P. A small jab - a big effect: nonspecific immunomodulation by vaccines. Trends Immunol. 2013 Sep;34:431. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kleinnijenhuis J, et al. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012 Oct 23;109:17537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen KJ, et al. Heterologous immunological effects of early BCG vaccination in low-birth-weight infants in Guinea-Bissau: a randomized-controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2015 Mar 15;211:956. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong M, et al. Trained immunity in newborn infants of HBV-infected mothers. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6588. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCall MB, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection causes proinflammatory priming of human TLR responses. J Immunol. 2007 Jul 1;179:162. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ataide MA, et al. Malaria-induced NLRP12/NLRP3-dependent caspase-1 activation mediates inflammation and hypersensitivity to bacterial superinfection. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Jan;10:e1003885. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Redelman-Sidi G, Glickman MS, Bochner BH. The mechanism of action of BCG therapy for bladder cancer--a current perspective. Nat Rev Urol. 2014 Mar;11:153. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart J. H. t., Levine EA. Role of bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of advanced melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2011 Nov;11:1671. doi: 10.1586/era.11.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grange JM, Stanford JL, Stanford CA, Kolmel KF. Vaccination strategies to reduce the risk of leukaemia and melanoma. J R Soc Med. 2003 Aug;96:389. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.8.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villumsen M, et al. Risk of lymphoma and leukaemia after bacille Calmette-Guerin and smallpox vaccination: a Danish case-cohort study. Vaccine. 2009 Nov 16;27:6950. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buffen K, et al. Autophagy controls BCG-induced trained immunity and the response to intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Oct;10:e1004485. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bianchi ME. DAMPs, PAMPs and alarmins: all we need to know about danger. JLeukoc Biol. 2007 Jan;81:1. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010 May;11:373. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mills KH. TLR-dependent T cell activation in autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011 Dec;11:807. doi: 10.1038/nri3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster SL, Hargreaves DC, Medzhitov R. Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin modifications. Nature. 2007 Jun 21;447:972. doi: 10.1038/nature05836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saeed S, et al. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science. 2014 Sep 26;345:1251086. doi: 10.1126/science.1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013 Jan 24;38:79. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanez A, et al. Detection of a TLR2 agonist by hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells impacts the function of the macrophages they produce. Eur J Immunol. 2013 Aug;43:2114. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ng RL, Bisley JL, Gorman S, Norval M, Hart PH. Ultraviolet irradiation of mice reduces the competency of bone marrow-derived CD11c+ cells via an indomethacin-inhibitable pathway. J Immunol. 2010 Dec 15;185:7207. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ng RL, et al. Altered immunity and dendritic cell activity in the periphery of mice after long-term engraftment with bone marrow from ultraviolet-irradiated mice. J Immunol. 2013 Jun 1;190:5471. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burgess SL, et al. Bone marrow dendritic cells from mice with an altered microbiota provide interleukin 17A-dependent protection against Entamoeba histolytica colitis. mBIO. 2014;5:e01817. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01817-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paust S, et al. Critical role for the chemokine receptor CXCR6 in NK cell-mediated antigen-specific memory of haptens and viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010 Dec;11:1127. doi: 10.1038/ni.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gillard GO, et al. Thy1+ NK [corrected] cells from vaccinia virus-primed mice confer protection against vaccinia virus challenge in the absence of adaptive lymphocytes. PLoSPathog. 2011 Aug;7:e1002141. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kleinnijenhuis J, et al. BCG-induced trained immunity in NK cells: Role for non-specific protection to infection. Clin Immunol. 2014 Dec;155:213. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nabekura T, et al. Costimulatory molecule DNAM-1 is essential for optimal differentiation of memory natural killer cells during mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Immunity. 2014 Feb 20;40:225. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Sullivan TE, Johnson LR, Kang HH, Sun JC. BNIP3- and BNIP3L-Mediated Mitophagy Promotes the Generation of Natural Killer Cell Memory. Immunity. 2015 Aug 18;43:331. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hendricks DW, et al. Cutting edge: NKG2C(hi)CD57+ NK cells respond specifically to acute infection with cytomegalovirus and not Epstein-Barr virus. J Immunol. 2014 May 15;192:4492. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Min-Oo G, Lanier LL. Cytomegalovirus generates long-lived antigen-specific NK cells with diminished bystander activation to heterologous infection. J Exp Med. 2014 Dec 15;211:2669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reeves RK, et al. Antigen-specific NK cell memory in rhesus macaques. Nat Immunol. 2015 Sep;16:927. doi: 10.1038/ni.3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee J, et al. Epigenetic Modification and Antibody-Dependent Expansion of Memory-like NK Cells in Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Individuals. Immunity. 2015 Mar 17;42:431. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saccani S, Pantano S, Natoli G. Two waves of nuclear factor kappaB recruitment to target promoters. J Exp Med. 2001 Jun 18;193:1351. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.12.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, et al. A unifying model for the selective regulation of inducible transcription by CpG islands and nucleosome remodeling. Cell. 2009 Jul 10;138:114. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ramirez-Carrozzi VR, et al. Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2beta nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes Dev. 2006 Feb 1;20:282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1383206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smale ST, Tarakhovsky A, Natoli G. Chromatin contributions to the regulation of innate immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:489. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghisletti S, et al. Identification and characterization of enhancers controlling the inflammatory gene expression program in macrophages. Immunity. 2010 Mar 26;32:317. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heinz S, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010 May 28;38:576. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barozzi I, et al. Coregulation of transcription factor binding and nucleosome occupancy through DNA features of mammalian enhancers. Mol Cell. 2014 Jun 5;54:844. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smale ST, Natoli G. Transcriptional control of inflammatory responses. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014 Nov;6:a016261. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nicodeme E, et al. Suppression of inflammation by a synthetic histone mimic. Nature. 2010 Dec 23;468:1119. doi: 10.1038/nature09589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ostuni R, et al. Latent enhancers activated by stimulation in differentiated cells. Cell. 2013 Jan 17;152:157. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaikkonen MU, et al. Remodeling of the enhancer landscape during macrophage activation is coupled to enhancer transcription. Mol Cell. 2013 Aug 8;51:310. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gosselin D, et al. Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell. 2014 Dec 4;159:1327. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lavin Y, et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014 Dec 4;159:1312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cheng SC, et al. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014 Sep 26;345:1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yoshida K, et al. The transcription factor ATF7 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced epigenetic changes in macrophages involved in innate immunological memory. Nat Immunol. 2015 Oct;16:1034. doi: 10.1038/ni.3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ifrim DC, et al. Defective trained immunity in patients with STAT1-dependent chronic mucocutaneaous candidiasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015 Apr 16; doi: 10.1111/cei.12642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luetke-Eversloh M, et al. Human cytomegalovirus drives epigenetic imprinting of the IFNG locus in NKG2Chi natural killer cells. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Oct;10:e1004441. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Eskandarian HA, et al. A role for SIRT2-dependent histone H3K18 deacetylation in bacterial infection. Science. 2013 Aug 2;341:1238858. doi: 10.1126/science.1238858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamon MA, Cossart P. Histone modifications and chromatin remodeling during bacterial infections. Cell Host Microbe. 2008 Aug 14;4:100. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bierne H, Hamon M, Cossart P. Epigenetics and bacterial infections. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012 Dec;2:a010272. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Monticelli S, Natoli G. Short-term memory of danger signals and environmental stimuli in immune cells. Nat Immunol. 2013 Aug;14:777. doi: 10.1038/ni.2636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet. 2010 Sep;11:597. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Apr 28;106:7113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ganeshan K, Chawla A. Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2014;32:609. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tannahill GM, et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2013 Apr 11;496:238. doi: 10.1038/nature11986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jha AK, et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015 Mar 17;42:419. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Donohoe DR, Bultman SJ. Metaboloepigenetics: interrelationships between energy metabolism and epigenetic control of gene expression. J Cell Physiol. 2012 Sep;227:3169. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gut P, Verdin E. The nexus of chromatin regulation and intermediary metabolism. Nature. 2013 Oct 24;502:489. doi: 10.1038/nature12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Benit P, et al. Unsuspected task for an old team: succinate, fumarate and other Krebs cycle acids in metabolic remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Aug;1837:1330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Carey BW, Finley LW, Cross JR, Allis CD, Thompson CB. Intracellular alpha-ketoglutarate maintains the pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2015 Feb 19;518:413. doi: 10.1038/nature13981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu TF, Vachharajani VT, Yoza BK, McCall CE. NAD+-dependent sirtuin 1 and 6 proteins coordinate a switch from glucose to fatty acid oxidation during the acute inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2012 Jul 27;287:25758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.362343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007 May;7:379. doi: 10.1038/nri2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clarke TB. Microbial programming of systemic innate immunity and resistance to infection. PLoS Pathog. 2014 Dec;10:e1004506. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ganal SC, et al. Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota. Immunity. 2012 Jul 27;37:171. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Host-pathogen interactions in sepsis. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2008 Jan;8:32. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Carson WF, Cavassani KA, Dou Y, Kunkel SL. Epigenetic regulation of immune cell functions during post-septic immunosuppression. Epigenetics. 2011 Mar;6:273. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.3.14017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ishii M, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the alternatively activated macrophage phenotype. Blood. 2009 Oct 8;114:3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-217620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mankad R. Atherosclerotic vascular disease in the autoimmune rheumatologic patient. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2015 Apr;17:497. doi: 10.1007/s11883-015-0497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bekkering S, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Riksen NP. The epigenetic memory of monocytes and macrophages as a novel drug target in atherosclerosis. Clin Ther. 2015 Apr 1;37:914. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bekkering S, et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014 Aug;34:1731. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Brasacchio D, et al. Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that coexist on the lysine tail. Diabetes. 2009 May;58:1229. doi: 10.2337/db08-1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yoshida K, Ishii S. Innate immune memory via ATF7-dependent epigenetic changes. Cell Cycle. 2015 Nov 10;:0. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1112687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kleinnijenhuis J, et al. Long-Lasting Effects of BCG Vaccination on Both Heterologous Th1/Th17 Responses and Innate Trained Immunity. J Innate Immun. 2013 Oct 30; doi: 10.1159/000355628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Locht C, Mielcarek N. Live attenuated vaccines against pertussis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Sep;13:1147. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.942222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Meyers PA, et al. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival--a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 1;26:633. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.14.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Muramatsu D, et al. beta-Glucan derived from Aureobasidium pullulans is effective for the prevention of influenza in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41399. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]