Abstract

Metagenomic sequencing increased our understanding of the role of the microbiome in health and disease, yet it only provides a snapshot of a highly dynamic ecosystem. Here, we show that the pattern of metagenomic sequencing read coverage for different microbial genomes contains a single trough and a single peak, the latter coinciding with the bacterial origin of replication. Furthermore, the ratio of sequencing coverage between the peak and trough provides a quantitative measure of a species' growth rate. We demonstrate this in vitro and in vivo, under different growth conditions, and in complex bacterial communities. For several bacterial species, peak to trough coverage ratios, but not relative abundances, correlated with the manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease and type II diabetes.

Characterization of microbiome composition and function through shotgun sequencing has provided many insights into its roles in health and disease. Gene calling (1, 2), functional/pathway analysis (3–6), metagenomic-wide association studies (7, 8), genome assembly (9, 10), and metagenomic single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection (11) have all shown associations between microbiome configurations and susceptibility to several diseases, including obesity (4, 12), type II diabetes (7), auto-inflammatory disorders (1, 13), metabolic disease (12, 14) and cancer (15, 16). However, these approaches, which only examine a static snapshot of the microbiome at the point of collection, cannot be used to observe the highly dynamic nature of the microbiota and the differential activity of its microbial members.

Here, we asked whether microbiota growth dynamics could be probed from a single metagenomic sample by examining the pattern of sequencing read coverage across bacterial genomes. Apart from a few examples (17), most bacteria harbor a single circular chromosome, which replicates bi-directionally from a single fixed origin towards a single terminus (18; Fig. 1A). Thus, during DNA replication, regions that have already been passed by the replication fork will have two copies while the yet unreplicated regions will have a single copy.

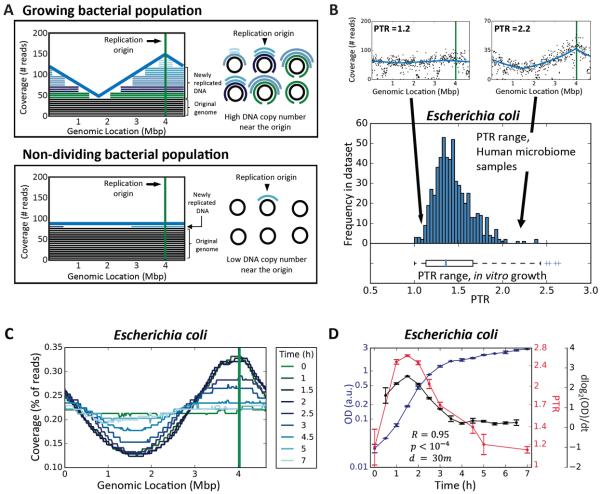

Fig. 1. Peak-to-trough coverage ratio (PTR) accurately measures in vitro growth rates of Escherichia coli.

(A) Sequenced reads (right) are mapped to complete bacterial genomes and the sequencing coverage across the genome is plotted. Each bacteria cell in a growing population (top) will be at a different stage of DNA replication, generating a coverage pattern that peaks near the known replication origin (green vertical line in graph), and thus produce a prototypical sequencing coverage pattern with a single peak and a single trough. Bacteria from a non-dividing population (bottom) have a single copy of the genome, producing a flat sequencing coverage pattern across the genome. (B) Above: sequencing coverage patterns of a non-replicating (left) and actively replicating (right) E. coli from two human gut metagenomic samples. Below: distribution of PTR of E. coli across 583 different human gut metagenomic samples (3, 7, 9; histogram) and 58 in vitro samples from four growth experiments (boxplot). (C) Genome coverage plots of E. coli, measured at different times during an in vitro cell growth experiment, showing that PTRs are highest during exponential growth (timepoints 1–2.5) and lowest in lag (timepoint 0) and stationary (timepoints 3–7) phases. (D) PTRs (red line) correlate (R=0.95, p<10−4) with the growth rate (black line), measured as the derivative of the logged abundance curve (abundance is measured as optical density of the culture; OD; blue line) in the subsequent 30 minutes (23). N=2. Symbols, mean; error bars, SEM.

This concept was previously used to detect the location of the replication origin in synchronized yeast colonies (19), but also holds true in an asynchronous bacterial population in which every cell may be at a different stage of replication. Summed across the population, the copy number of a DNA region will be higher the closer that region is to the replication origin and, conversely, lower the closer that region is to the terminus (20, 21). Hence, the ratio between DNA copy number near the replication origin and that near the terminus, which we term peak-to-trough ratio (PTR), should reflect the growth rate of the bacterial population. At higher growth rates, a larger fraction of cells undergo DNA replication and more active replication forks are present in each cell (22). This results in a ratio higher than 1:1 between near-origin DNA and near-terminus DNA, thereby providing a quantitative readout of the population growth rate (21).

We grew in vitro cultures of Escherichia coli (K-12 strain) and sequenced them at multiple time points during late lag phase, exponential phase, and early stationary phase (23). During stationary phase, when most of the cells in the culture are not growing and thus have a single copy of their genome, we found uniform coverage across the genome (Fig. 1A–C). In contrast, during exponential growth, when each bacterial cell may be at a different stage of DNA replication, the coverage pattern exhibited a single trough and a single peak, and the peak coincided with the known (24) replication origin (Fig. 1A–C).

Similar patterns to those seen in vitro were also found for E. coli in 583 publicly available (3, 7, 9) human metagenomic fecal samples (Fig. 1B). PTRs extracted from these samples varied across individuals, in the range of 1–2.4, resembling the 1–2.6 range of ratios measured in vitro (Fig. 1B). Ratios higher than 2 are indicative of multifork replication, previously documented for E. coli (18, 22).

To examine whether PTRs provide a quantitative measure of growth rate, we calculated the temporal growth rate of E. coli at different times during its growth experiment, as the derivative of its abundance across time (23). PTRs were correlated with the measured growth rate, preceding it by 30 minutes (R=0.95, p<10−4, Fig. 1D), indicating that PTR predicts the change in abundance. To test whether PTRs accurately reflect steady state growth rates (as opposed to temporal growth), we grew E. coli in an aerobic chemostat in which steady growth rates were controlled by changing the dilution rate of the system to induce a 16-fold range (23), and found excellent correlation (R=0.996, p<0.001; Fig. S1A) between the calculated PTRs and the measured growth rates. According to theoretical models (21), PTR=2C/G, where C is the replication time (C-period), and G is the generation time, and thus 1/log2(PTR) is proportional to G/C. This transformation was correlated with measured bacterial generation time (R=0.96, p<0.01; Fig S1B), confirming PTR as its proxy, even when the replication time is unknown.

The relationship between PTR and growth rate extends to other commensal strains, as we found that PTR and temporal measured growth rate were significantly correlated in similar cell growth experiments performed on Lactobacillus gasseri and Enterococcus faecalis under anaerobic conditions (L. gasseri, R=0.74, p<0.001; and E. faecalis, R=0.57, p<0.05; Fig. S2A, B). PTR also detects changes in growth rate mediated by changes in growth conditions, as PTRs and measured growth rate were correlated in additional cell growth experiments performed on E. faecalis in aerobic conditions, and on E. coli in restricted growth conditions (23; E. coli, R=0.92, p<0.001; E. faecalis, R=0.78, p<10−4; Fig. S2C, D). L. gasseri exhibited no growth in aerobic conditions, and accordingly we observed no change in PTRs (Fig. S2E). PTRs for L. gasseri and E. faecalis were significantly different between aerobic and anaerobic conditions (E. faecalis, p<0.05; L. gasseri, p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test, Fig. S2E).

To examine whether PTRs can be used to detect clinically relevant changes in culture conditions, we treated an in vitro culture of early log-phase nalidixic acid-resistant Citrobacter rodentium with the bacteriostatic antibiotic erythromycin. Since bacteriostatic antibiotics halt bacterial growth, and thus indirectly inhibit replication, we postulated that erythromycin treatment would decrease PTRs. As control, cultures were treated with nalidixic acid, with the bactericidal antibiotic kanamycin, or left untreated. Indeed, erythromycin treatment lowered the PTR compared with controls (Mann-Whitney p<0.001 and p<10−4 for untreated control or nalidixic acid treated control, respectively; Fig. 2A, B). PTR reduction under erythromycin was evident within 30 minutes after administration, and preceded the halt in exponential growth that was detected only 60 minutes after erythromycin treatment (Fig. 2A–C). During antibiotic recovery, obtained by washing the cultures after 2.5 hours and removing the antibiotics (23), PTRs increased, consistent with the rise in abundance (Mann-Whitney p<0.001; Fig. 2A, B).

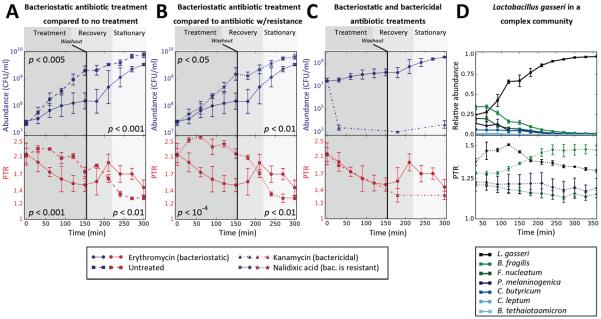

Fig. 2. Peak-to-trough coverage ratio (PTR) accurately measures in vitro growth rates in multiple conditions.

(A–C) Absolute abundance levels (colony forming units per ml; CFU/ml; top y-axis, blue) and PTR (bottom y-axis, red) as a function of time (minutes) of an in vitro culture of Citrobacter rodentium treated with erythromycin (bacteriostatic antibiotic in this setting, N=2), compared to those of (A) An untreated control culture (N=3); (B) A culture treated with nalidixic Acid, a drug to which C. rodentium is resistant (N=3); and (C) A culture treated with kanamycin, a bactericidal drug in this setting (N=3). Background color indicates the treatment period (dark gray, left), recovery period (gray, middle) and early stationary phase (light gray, right). The black vertical line denotes antibiotic washout. PTR changes precede changes in growth. P-values are Mann-Whitney U-test between abundance (top) or PTR (bottom) of the two different cultures show, at times 30–150 minutes (left) or times 210–300 minutes (right). (D) Bacterial abundances (CFU/ml; top panel) and PTR (bottom panel) of L. gasseri and a mixture of six additional bacterial strains that inhabit the human gut. N=4. Symbols, mean; error bars, SEM.

Next, we grew L. gasseri within a mixture of six commensal bacterial strains (23) and observed a rise in its PTR corresponding with the rise in abundance, with PTR and temporal growth being correlated (R=0.64, p<0.001; Fig. 2D).

Together, the in vitro experiments show that PTRs precede and predict changes in abundance even in the more complex setting of a mixed bacterial community, thereby establishing the link between PTRs and growth rate.

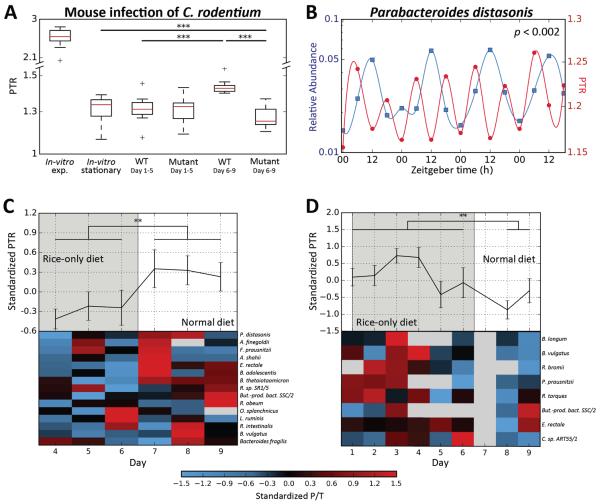

To test whether PTRs remained accurate predictors of bacterial activity in a disease setting, we compared the proliferative behavior of a virulent and non-virulent (tir-mutant) strains of C. rodentium, which we used to infect C57BL/6 mice previously depleted of their native microbiota by wide-spectrum antibiotic treatment (23). We compared the in vivo abundance of both strains with PTRs and found that both showed similar behaviors 1-5 days post-infection (p.i.), with counts steadily rising from ~104–105 CFU/ml at day 1 to ~108 CFU/ml by day 5 (Fig. S3). However, at 6-9 days p.i. the virulent strain displayed significantly higher counts (Mann-Whitney p<0.05, Fig. S3) and PTRs (Mann-Whitney p<0.001; Fig. 3A) than the non-virulent strain, likely reflecting preferential mucosal adhesion and proliferation (25). While PTRs of the virulent strain were higher at days 6-9 p.i. compared with days 1-5 p.i. (Mann-Whitney p<0.001; Fig. 3A), PTRs of the non-virulent strain 6-9 days p.i. were even lower than those of in vitro cultures of C. rodentium in stationary phase (Mann-Whitney p<0.001; Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. Peak-to-trough ratios (PTR) reflect the growth dynamics of in vivo microbial communities.

(A) Shown are PTRs of virulent (icc169; WT; N=3) and non-virulent (tir mutant; N=3) Citrobacter rodentium 1-5 or 6-9 days post infection (p.i.) of C57BL/6 mice previously depleted of their native microbiota. PTR of stationary and exponential in vitroC. rodentium cultures are shown for reference. P-values are Mann-Whitney U-test. See Fig. S3 for the corresponding measured abundances. (B) Relative abundance (left y-axis, blue) and PTRs (right y-axis, red) of Parabacteroides distasonis from fecal metagenomic samples obtained approximately every 6 hours from one human individual in 4 consecutive days (26). Plotted lines are spline interpolations using the displayed data points. Time is with respect to light cycles (Zeitgeber time, horizontal axis). P-value is for 24 hour oscillations (23). (C, D) Shown are standardized PTRs (top graphs, mean ± SEM) and specific PTRs for species present in the sample (bottom heatmaps), belonging to two human subjects that underwent a radical dietary change. Compared are days in which only white boiled rice was consumed (grey area) and days of normal diet (white area). A global change in bacterial growth dynamics was observed between dietary regimens (** - Mann-Whitney p<0.005, *** - p<0.001).

To explore the utility of the PTR measure within the complex metagenomic setting we devised a computational pipeline that extracts PTRs for multiple samples within large metagenomic cohorts (Supplementary online text, 23 and Fig. S4). In devising this pipeline, we took care to address (1) genomic differences between strains of a certain species; (2) copy number variation of different genomic regions and (3) variable coverage levels stemming from sequencing depth. We show that our method is robust to these drivers of noise (Fig. S5–8, supplementary online text), attributed to our examination of coverage across the entire genome, as opposed to comparing the coverage of origin and terminus regions directly.

Examining the full length of the genome also allows us to predict the replication origin location in different bacteria. We verified that coverage peak locations coincided with known locations of origins of replication. To this end, we applied our pipeline to 759 metagenomic stool samples from Chinese and European cohorts (7, 9) and predicted the location of the origin and terminus of replication for 187 different microbial strains. Indeed, these predictions, computed solely based on our analysis of the bacterial genome coverage patterns, agreed with the known replication origins of 132 different strains (24; R2=0.98, p<10−30, Fig. S8), and for 55 strains whose replication origin location is unknown our method generated novel predictions (Fig. S9).

To test whether PTRs can uncover a possible interplay between host genetics and gut microbiome growth dynamics we collected fecal samples from three mouse strains (Swiss Webster, BALB/c and C57BL/6, 23) grown under identical environmental conditions. Microbiota growth dynamics, as estimated by PTRs, differed significantly across the different mouse strains. In BALB/c mice, PTRs were lower overall compared with C57BL/6 and Swiss Webster mice (p<0.05; Fig. S10A). The reduction in growth in the BALB/c mice was driven by Parabacteroides distasonis, which displayed consistently lower PTR than in other mouse strains (Fig. S10B–D), indicating that host genetics may affect the growth dynamics of this bacterium.

Another example to the utility of PTRs in assessing physiological microbiome behavioral patterns is provided in microbiome diurnal oscillation patterns, which we recently linked to host susceptibility to obesity and glucose intolerance (26). Examining PTRs of fecal microbiomes collected from a human volunteer every 6 hours for four consecutive days, we identified two species, out of four that passed our PTR pipeline filters, that showed abundance levels cycling with a 24 hour periodicity (23). For both species, the PTRs also exhibited 24 hour oscillatory patterns (p<0.05; 23; Fig. 3B, S11), suggesting that diurnal changes in the abundance of some bacteria were reflected in their PTRs.

To test the impact of an extreme dietary change on bacterial growth rates, two healthy human volunteers underwent an acute dietary change, in which they shifted their normal diet to one that contained only boiled white rice for one week, after which they reverted back to their regular dietary habits. In both participants, we observed a global change in gut bacterial growth dynamics between dietary regimens, as reflected in statistically significant differences in the PTRs of all bacteria between the days in which rice was consumed and the days in which the participant's regular diet was followed (P<0.005 for each participant; Fig. 3C,D).

We also examined body site-specific microbial growth rates in a metagenomic cohort (3) and found significantly higher PTRs in 229 tongue dorsum (1.36±0.006) and 193 buccal mucosa (1.37±0.007) samples, as compared with 325 stool samples (1.16±0.002; p<10−50in both cases; Fig. S12). Six species were present in both the oral cavity and stool with sufficient coverage to calculate PTRs, with three featuring significantly different PTRs between sites (FDR-corrected Mann-Whitney p<0.1; Fig. S12B–G), indicating that inter-site differences stem not only from distinct bacterial compositions, but also from site-specific differences in growth dynamics.

Overall, these results provide examples of functional insights that are not achievable using traditional metagenomics analysis methods, and indicate that microbiome growth dynamics vary across diverse physiological conditions and locations.

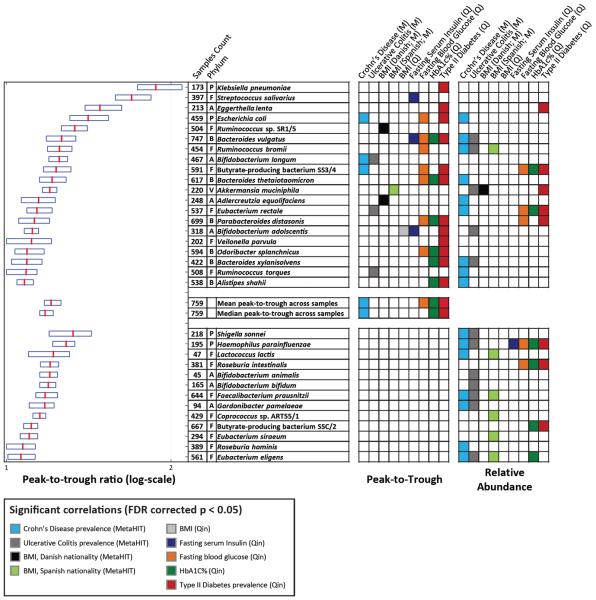

To test whether bacterial PTRs are associated with disease and different clinical parameters, we generated PTRs for every species in samples from European (N=396; 9) and Chinese (N=363; 7) cohorts. In both datasets, we found large variation in PTRs across samples (Fig. 4). Notably, we found statistically significant associations between the PTRs of 20 different bacteria and multiple clinical parameters, including significant correlations between the PTR of Bifidobacterium longum and occurrence of Crohn's disease in the Spanish nationals of the European cohort (9; FDR-corrected Mann-Whitney p<0.005; Fig. 4), and between the PTRs of 12 different bacteria and the occurrence of type II diabetes in the Chinese cohort (7). We also found significant correlations between PTRs and the occurrence of ulcerative colitis, body-mass index (BMI), the fraction of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c%, a common marker of long-term glycemic control; 27), fasting serum insulin, and fasting blood glucose levels (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Bacterial dynamics correlate with several diseases and metabolic disorders.

Peak-to-trough ratios (PTR) of species from Chinese (7; N=363; Q) and European (9; N=396; M) cohorts are shown (boxplots, left; red-median; boundaries-25–75th percentiles) if its relative abundances or PTRs were significantly associated with clinical parameters. Shown are phylum membership; the number of samples for which PTRs were calculated; and a row with colored entries for each statistically significant (FDR-corrected p<0.05) association between clinical parameters and its PTR (left column block) or relative abundance (right column block). Mann-Whitney U-test and Spearman correlations were used for binary and continuous clinical parameters, respectively. Top-block: species with significant associations between PTR and clinical parameters; bottom-block: species with significant associations only between relative abundance and clinical parameters. A-Actinobacteria, B-Bacteroidetes, E- Euryarchaeota. F-Firmicutes, P-Proteobacteria, V-Verrucomicrobia

These associations are independent of- and unobtainable by examining bacterial abundances, as: (1) in correlating PTRs with clinical parameters we only used samples in which that bacteria was present, thereby withholding information about the presence or absence of the examined bacteria (23); (2) in only five of the 38 statistically significant correlations were the abundance levels also correlated with the same clinical parameter; and (3) 36 of the 38 significant associations of PTR remained significant after correcting them for relative abundance levels. The PTR of some species were correlated with clinical parameters only after correction for relative abundance, including Eubacterium rectale and the occurrence of Crohn's disease (FDR corrected Mann-Whitney p<10−4).

As a global measure of the growth dynamics of the entire microbiota, for every sample we calculated both the mean and median of the PTRs of all of the bacteria present. This global measure correlated with fasting glucose and HbA1c% levels and with the occurrence of Crohn's disease and type II diabetes, indicating that global microbiome growth dynamics also associate with disease (Fig. 4).

A preliminary analysis of 40 samples from the Prospective Registry in IBD Study at MGH (PRISM) cohort (23) showed that only four bacteria passed our stringent pipeline filters for PTR calculation in more than half of the samples. Notwithstanding, Eggerthella lenta presented significantly different PTRs between patients with active Crohn's disease and patients in remission (FDR corrected Mann-Whitney p<0.1). Neither the abundance of E. lenta, nor of the other three species differed between active and quiescent Crohn's patients, highlighting the fact that PTRs reflect an independent feature of the effect of the gut microbiome on its host.

Overall, we present a new type of metagenomic data analysis that provides an accurate quantitative estimate of the growth dynamics of the microbiota from a single snapshot sample. These estimates have clinical relevance and correspond to changes in absolute abundances, which are masked by and unobtainable through relative abundances.

Using PTRs to 'fish out' microbial kinetic behavior in a complex microbiome population could extend our understanding of how flexibly the microbiota responds functionally to environmental signals. We may be able to identify active 'driver' and 'modulator' species, distinguish them from bystander commensal species and pinpoint disease-causing or disease-modulating microbes that contribute to multi-factorial diseases whose activities may be masked by other bacteria. Furthermore, our method may be able to detect, follow, and assess therapeutic responsiveness of pathogenic, or probiotic species introduced into the microbiome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Segal and Elinav labs for fruitful discussions. T.K. and D.Z. are supported by the Ministry of Science, Technology & Space, Israel. T.K. is the recipient of the Strauss Institute fellowship for nutritional research. C.A.T. is the recipient of a Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds PhD Fellowship. E.E. is supported by Yael and Rami Ungar, Israel; Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust; the Gurwin Family Fund for Scientific Research; Crown Endowment Fund for Immunological Research; estate of Jack Gitlitz; estate of Lydia Hershkovich; the Benoziyo Endowment Fund for the Advancement of Science; Adelis Foundation; John L. and Vera Schwartz, Pacific Palisades; Alan Markovitz, Canada; Cynthia Adelson, Canada; CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique); estate of Samuel and Alwyn J. Weber; Mr. and Mrs. Donald L. Schwarz, Sherman Oaks; grants funded by the European Research Council; the German-Israel Binational foundation; the Israel Science Foundation; the Minerva Foundation; the Rising Tide foundation; E.E. is the incumbent of the Rina Gudinski Career Development Chair. This work was supported by grants from the European Research Council (ERC) and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) to E. S.

The European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) accession number for the microbial shotgun sequences is PRJEB9718.

Footnotes

Author contributions T.K. and D.Z. conceived the project, designed and conducted the analyses, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. J.S. devised and performed all experiments in mice, anaerobic, and pathogenic bacteria. A.W. directed some of the experiments, and the production of libraries and sequencing from samples collected in this study and provided critical insights to the manuscript. T.K., D.Z., J.S. and A.W. equally contributed to this work. T.A.S., M.P.L. and E.M. performed experiments and extraction and sequencing of samples. M.P.F. performed experiments. G.J. performed chemostat experiments. A.H. supervised germ free mouse experiments. N.C. aided in the design of the computational pipeline and in conducting the analyses. A.S.M. and R.X. directed the PRISM cohort. C.A.T. and E.E. directed the circadian experiments. R.S. and E.S. directed the dietary intervention study. E.E. and E.S. conceived and directed the project and analyses, designed experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript.

References and Notes

- 1.Qin J, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rho M, Tang H, Ye Y. FragGeneScan: predicting genes in short and error-prone reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Human T, Project M. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature. 2012;486:207–14. doi: 10.1038/nature11234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbaugh PJ, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Markowitz VM, et al. IMG/M-HMP: a metagenome comparative analysis system for the Human Microbiome Project. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40151. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer F, et al. The metagenomics RAST server - a public resource for the automatic phylogenetic and functional analysis of metagenomes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin J, et al. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2012;490:55–60. doi: 10.1038/nature11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson FH, et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature. 2013;498:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen HB, et al. Identification and assembly of genomes and genetic elements in complex metagenomic samples without using reference genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014;32:822–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh J, et al. Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature. 2014;514:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schloissnig S, et al. Genomic variation landscape of the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2013;493:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature11711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Chatelier E, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature. 2013;500:541–6. doi: 10.1038/nature12506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manichanh C, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn's disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55:205–11. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.073817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlsson F, Tremaroli V, Nielsen J, Bäckhed F. Assessing the human gut microbiota in metabolic diseases. Diabetes. 2013;62:3341–9. doi: 10.2337/db13-0844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn J, et al. Human gut microbiome and risk for colorectal cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1907–11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimoto S, et al. Obesity-induced gut microbial metabolite promotes liver cancer through senescence secretome. Nature. 2013;499:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinnebusch J, Tilly K. Linear plasmids and chromosomes in bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 1993;10:917–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang JD, Levin PA. Metabolism, cell growth and the bacterial cell cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:822–7. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu J, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of replication origins by deep sequencing. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R27. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-4-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skovgaard O, Bak M, Løbner-Olesen A, Tommerup N. Genome-wide detection of chromosomal rearrangements, indels, and mutations in circular chromosomes by short read sequencing. Genome Res. 2011;21:1388–93. doi: 10.1101/gr.117416.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bremer H, Churchward G. An examination of the Cooper-Helmstetter theory of DNA replication in bacteria and its underlying assumptions. J. Theor. Biol. 1977;69:645–54. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(77)90373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper S, Helmstetter CE. Chromosome replication and the division cycle of Escherichia coli B/r. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;31:519–40. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.See supplementary materials on Science Online for details.

- 24.Gao F, Luo H, Zhang C-T. DoriC 5.0: an updated database of oriC regions in both bacterial and archaeal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D90–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiles S, et al. Organ specificity, colonization and clearance dynamics in vivo following oral challenges with the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Cell. Microbiol. 2004;6:963–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thaiss CA, et al. Transkingdom Control of Microbiota Diurnal Oscillations Promotes Metabolic Homeostasis. Cell. 2014;159:514–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koenig RJ, et al. Correlation of glucose regulation and hemoglobin AIc in diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976;295:417–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197608192950804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francis OE, et al. Pathoscope: species identification and strain attribution with unassembled sequencing data. Genome Res. 2013;23:1721–9. doi: 10.1101/gr.150151.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suez J, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514:181–186. doi: 10.1038/nature13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koch V, et al. Effect of antifoam agents on the medium and microbial cell properties and process performance in small and large reactors. Process Biochem. 1995;30:435–446. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusova T, Ciufo S, Fedorov B, O'Neill K, Tolstoy I. RefSeq microbial genomes database: new representation and annotation strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D553–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flicek P, et al. Ensembl 2014. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D749–55. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marco-Sola S, Sammeth M, Guigó R, Ribeca P. The GEM mapper: fast, accurate and versatile alignment by filtration. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:1185–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Newville M, Ingargiola A, Stensitzki T, Allen DB. Zenodo. 2014. LMFIT: Non-Linear Least-Square Minimization and Curve-Fitting for Python. doi:10.5281/zenodo.11813. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB, Kornacker K. JTK_CYCLE: an efficient nonparametric algorithm for detecting rhythmic components in genome-scale data sets. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2010;25:372–80. doi: 10.1177/0748730410379711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:357–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.