Abstract

Purpose

The approved dose of ipilimumab is 3 mg/kg infused over 90 minutes; however, in clinical trials, 10 mg/kg has also been infused over 90 minutes. At this higher dose, patients receive 3 mg/kg within the first 27 minutes of treatment. We sought to determine whether the standard dose of 3 mg/kg could be safely infused over 30 minutes.

Methods

We reviewed retrospectively the incidence of infusion-related reactions (IRRs) to ipilimumab at our institution in patients receiving doses of either 3 or 10 mg/kg infused over 90 minutes. Our findings led to a change in institutional guidelines for ipilimumab infusion time from 90 minutes to 30 minutes. We reviewed the first 14 months of our prospective experience using a 30-minute infusion of ipilimumab.

Results

Between April 1, 2008, and June 30, 2013, 595 patients received 2,507 doses of ipilimumab infused at either 3 mg/kg (n = 457) or 10 mg/kg (n = 138) over 90 minutes. Although the 10 mg/kg group had a higher incidence of IRRs (4.3%) than the 3 mg/kg group (2.2%), this difference was not statistically significant (P = .22). In 120 patients treated prospectively with ipilimumab 3 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes, seven patients (5.8%) had an IRR (P = .06 compared with 90-minute infusions). All IRRs occurred at dose 2; six were grade 2, and one was grade 3. All seven patients received subsequent doses of ipilimumab safely, the majority with premedication.

Conclusion

Ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg can be infused safely over 30 minutes with an acceptably low incidence of IRRs. After an IRR, patients can safely receive additional doses of ipilimumab with premedication.

INTRODUCTION

Ipilimumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody directed against the T-cell coinhibitory marker cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4. Ipilimumab was approved in March 2011 by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Ipilimumab was the first drug for metastatic melanoma associated with an improvement in overall survival.1 Ipilimumab is now approved worldwide and is one of the most common drugs used as front-line treatment for metastatic melanoma.

The approved dose and schedule for ipilimumab is 3 mg/kg infused over 90 minutes administered every 3 weeks for up to four doses. The basis for the 90-minute infusion requirement is unclear, but it presumably was intended to minimize the incidence of infusion-related reactions (IRRs). Nevertheless, there are few published data on the incidence of IRRs caused by ipilimumab. In a phase I pharmacokinetic study of ipilimumab with or without one of two different chemotherapy regimens, three of 20 patients receiving ipilimumab alone required infusion interruption.2 In a phase I/II study of ipilimumab, two of 88 patients were reported to have had a grade 1 IRR, which resolved with symptomatic treatment.3 Notably, no ipilimumab IRRs were reported in the two landmark randomized, controlled, phase III trials.1,4

Clinical trials evaluating ipilimumab doses of 10 mg/kg also used a 90-minute infusion. We reasoned that in these patients, the standard dose of 3 mg/kg had been administered in the first 27 minutes. This suggested that a standard 3 mg/kg dose of ipilimumab might be safely administered over 30 minutes, potentially leading to improved efficiency and convenience.

To test this hypothesis, we retrospectively reviewed the incidence of IRRs in patients treated at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center with either the 3 or 10 mg/kg doses given over 90 minutes. We then treated a cohort of patients prospectively with ipilimumab 3 mg/kg using a 30-minute infusion. In this report, we present the incidence of IRRs in both the retrospective and prospective cohorts.

METHODS

Using computerized pharmacy records, we retrospectively reviewed all patients with metastatic solid tumor malignancies who received at least one dose of ipilimumab at either the 3 or 10 mg/kg dose between April 1, 2008, and June 30, 2013. All patients who received the 10 mg/kg dose and some patients who received the 3 mg/kg dose were treated as part of a clinical trial. In some clinical trials, maintenance ipilimumab (every 3 months) was allowed. After 2011, most patients who received the 3 mg/kg dose were treated off protocol as a standard of care. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they were treated with ipilimumab in combination with any other drug. Patients on blinded studies (10 mg/kg v placebo) were also excluded unless the treatment code had been broken and the patient was known to have received ipilimumab or unless the patient had an IRR even if the treatment cohort was not known. All patients in these retrospective cohorts received ipilimumab over 90 minutes.

After the change in institutional guidelines for ipilimumab infusion from 90 minutes to 30 minutes for nonprotocol patients, we prospectively collected data on all patients with metastatic melanoma treated with ipilimumab. All received 3 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes. We included in this analysis all patients who had completed their intended course of ipilimumab treatment. None of these patients were on a clinical trial. Patients who had received a prior course of ipilimumab were excluded.

For both the retrospective and prospective analyses, patient medical records were reviewed for the purposes of data collection and confirmation of any IRRs. Data collected included age, sex, stage, prior therapies, history of brain metastases, dose of ipilimumab, number of doses given, patient weight, total ipilimumab dose administered, time of IRR, amount of ipilimumab infused at the time of IRR, management of IRR, and outcome. Institutional review board approval was obtained for all analyses.

IRRs were reported and recorded prospectively but graded retrospectively according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.5 Grade 2 IRRs are defined as reactions that respond promptly to symptomatic treatment; grade 3 IRRs are defined as non–life-threatening reactions with prolonged symptoms, recurrence of symptoms after initial improvement, or reactions that require hospitalization. IRRs were treated according to our standard institutional guidelines for the management of IRRs caused by biologic therapy.

RESULTS

Retrospective Cohort: Comparing the Incidence of IRRs in Patients Treated With Ipilimumab 3 or 10 mg/kg Infused Over 90 Minutes

Between April 1, 2008, and June 30, 2013, 2,507 doses of ipilimumab were administered to 595 patients at either 10 mg/kg (138 patients; 776 doses) or the standard dose of 3 mg/kg (457 patients; 1,731 doses). Five hundred forty-three patients had metastatic melanoma (Appendix Table A1, online only), and 52 patients had other solid malignancies including carcinomas of the lung, breast, and prostate.

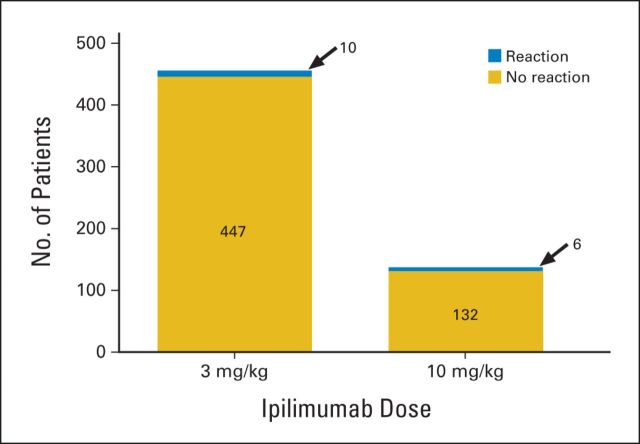

Of the 138 patients who received the 10 mg/kg dose, 26 (19%) received only one dose, 21 (15%) received two doses, 19 (14%) received three doses, and 22 (16%) received all four doses. Fifty patients (36%) received more than four doses as part of clinical trials that allowed maintenance therapy every 3 months. Of the 457 patients who received 3 mg/kg, 40 (9%) received only one dose, 57 (12%) received two doses, 66 (14%) received three doses, and 237 (52%) received all four doses. Fifty-seven patients (12%) received more than four doses as part of several clinical trials. The percentages of patients who had an IRR at the 10 mg/kg and 3 mg/kg dose levels were 4.3% (six of 138 patients) and 2.2% (10 of 457 patients), respectively (Fig 1). This difference was not statistically significant (P = .22, Fisher's exact test). All IRRs occurred during infusions; none were reported after completion of the infusion. Fifteen of 16 patients had grade 2 IRRs. There was one possible grade 3 IRR (hypotension) in a patient receiving the third dose of 10 mg/kg over 90 minutes.

Fig 1.

Incidence of infusion-related reactions with 90-minute infusions. Patients received either 3 mg/kg (457 patients) or 10 mg/kg (138 patients). Stacked bar graphs indicate patients who did not have an infusion reaction (gold bars) and those who did have a reaction (blue bars). Infusion reactions were seen in 10 patients (2.2%) and six patients (4.3%) at the 3 and 10 mg/kg doses, respectively (P = .22, Fisher's exact test).

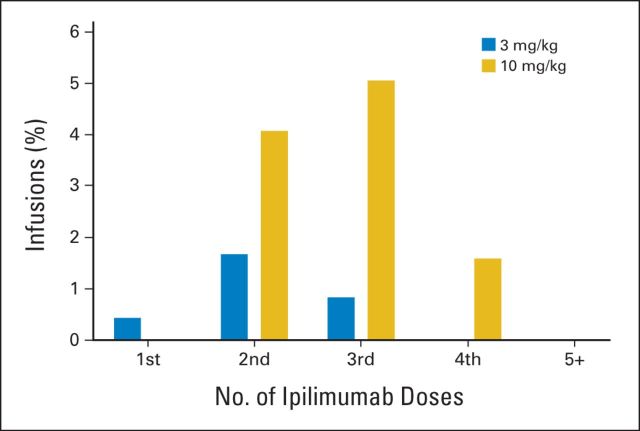

The distribution of IRRs by dose number is shown in Figure 2. At the 3 mg/kg dose, all IRRs were grade 2 and were most common after the second infusion (1.7% of second infusions resulted in IRRs); none were observed beyond dose 3. Of the 10 patients experiencing IRRs, nine received subsequent doses of ipilimumab. The one patient who did not receive subsequent doses had progression of disease and died shortly after dose 1. Of the nine patients who received subsequent doses, eight received premedication for the subsequent doses. Despite premedication, one patient had a subsequent IRR. One patient did not receive premedication for dose 3 and did not experience another IRR. At 10 mg/kg, IRRs were seen after the second, third, or fourth infusions, although at this higher dose, IRRs were most common after the third infusion (5% of third infusions resulted in IRRs).

Fig 2.

Initial infusion reactions according to dose and treatment number. Infusion reactions that occurred with the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth or greater infusions in patients treated at 3 mg/kg (blue bars) and 10 mg/kg (gold bars) are shown. For patients who had infusion reactions during subsequent ipilimumab doses, only the first infusion reaction in each patient is indicated.

These data indicated that the incidence of IRRs at 10 mg/kg was not significantly higher than at 3 mg/kg and implied that ipilimumab could be safely administered over 30 minutes. As a result, the Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center agreed to establish an institutional standard of a 30-minute ipilimumab infusion for nonprotocol patients as of October 21, 2013. A 1-hour observation period was maintained after the first ipilimumab dose.

Prospective Cohort: Incidence of IRRs in Patients Treated With Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg Infused Over 30 Minutes

After 14 months under the new treatment guidelines, 120 patients with metastatic melanoma had completed their intended course of ipilimumab therapy of 3 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes (Table 1). A total of 395 doses of ipilimumab were administered. The majority of patients had not received prior treatment, although five patients had received prior anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 antibodies as part of a clinical trial. Eleven patients (9.2%) received only one dose of ipilimumab, 19 (15.8%) received two doses, 13 (10.8%) received three doses, and 77 (64.2%) received all four doses. Ten of 11 patients discontinued ipilimumab after dose 1 because of progressive disease (usually CNS), and one patient developed severe pneumonitis felt to be related to prior immunotherapy. Eight of 19 patients discontinued ipilimumab after dose 2 because of progressive disease, four of 19 patients died after the second dose, and seven of 19 patients discontinued treatment because of immune-related adverse events (colitis, n = 4; neuropathy, n = 3). Five of 13 patients discontinued after dose 3 as a result of progressive disease, two of 13 patients died shortly after the third dose, and six of 13 patients discontinued as a result of immune-related adverse events (colitis, n = 5; hypophysitis, n = 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients Treated Prospectively With Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg Infused Over 30 Minutes

| Characteristic | No. of Patients (N = 120) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 78 |

| Female | 42 |

| Age, years | |

| Median | 64 |

| Range | 33-91 |

| Stage of cutaneous melanoma at treatment start | 105 |

| IIIB | 5 |

| IIIC | 14 |

| IVM1a | 6 |

| IVM1b | 19 |

| IVM1c | 61 |

| Ballantyne stage of mucosal melanoma at treatment start | 11 |

| I | 1 |

| II | 2 |

| III | 8 |

| Stage of ocular melanoma at treatment start | 4 |

| IV | 4 |

| Known brain metastasis at treatment start | |

| Yes | 43 |

| No | 77 |

| Previous treatments | |

| None | 86 |

| Chemotherapy | 8 |

| Anti-PD1 or anti-PDL1 | 5 |

| BRAF or MEK inhibitor | 21 |

| Total ipilimumab doses received per patient | |

| 1 | 11 |

| 2 | 19 |

| 3 | 13 |

| 4 | 77 |

Seven (5.8%) of 120 patients experienced an IRR. All seven patients experienced the IRR at the second dose of ipilimumab. This proportion of patients experiencing an IRR is consistent with our previous observations in patients receiving 10 mg/kg over 90 minutes (4.3%) in which patients received the initial 3 mg/kg dose in 30 minutes. Although this is a low incidence of IRRs, it is somewhat higher than the incidence of IRRs using the standard infusion rate of 90 minutes (2.2%) but of borderline statistical significance (P = .06, Fisher's exact test). Six IRRs were grade 2 (Table 2), and only one was grade 3. These IRRs are described in the following section.

Table 2.

IRRs Among Patients Treated With Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg Infused Over 30 Minutes

| Patient No. | KPS/ECOG | Dose No. | Dose (mg) | Time of IRR (minutes into/after the infusion) | IRR CTCAE Grade | Premedication at Dose 3 | Dose 3 Infusion Time (minutes) | IRR at Dose 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KPS 90 | 2 | 330 | 4 | 2 | No | 45 | No |

| 2 | KPS 90 | 2 | 300 | 10 | 2 | No | 90 | Yes* |

| 3 | ECOG 1 | 2 | 270 | 20 | 2 | Yes | 90 | No |

| 4 | ECOG 0 | 2 | 200 | 6 | 2 | Yes | 90 | No |

| 5 | KPS 90 | 2 | 200 | 15 | 3 | Yes | 90 | No |

| 6 | ECOG 2 | 2 | 290 | 30 min after | 2 | Yes | 90 | No |

| 7 | ECOG 1 | 2 | 200 | Immediately after | 2 | Yes | 30 | No |

Abbreviations: CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IRR, infusion-related reaction; KPS, Karnofsky performance score.

Patient 2 experienced an IRR at dose 3 and responded rapidly to treatment. Dose 4 was given with premedication without incident.

Management of IRRs in Patients Treated With Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg Infused Over 30 Minutes

Patient 1.

A 50-year-old man with metastatic melanoma, atrial fibrillation, and hypertension received stereotactic radiosurgery to his brain metastases and was then started on ipilimumab. He tolerated dose 1 without incident. Four minutes into dose 2, the patient reported a warm sensation and experienced facial flushing with transient chest discomfort (grade 2). The infusion was stopped. Electrocardiogram was normal, and vital signs were stable. The patient received diphenhydramine 25 mg intravenously (IV) and famotidine 20 mg IV with immediate symptom relief. The remainder of the infusion was administered over 60 minutes without incident. The patient received dose 3 without premedication infused over 45 minutes without incident. The patient did not receive dose 4 because of progression of disease necessitating a change in treatment.

Patient 2.

A 61-year-old man with metastatic melanoma of unknown primary tolerated dose 1 without incident. Ten minutes into dose 2, the patient reported acute abdominal and back pain (grade 2). The infusion was stopped. Diphenhydramine 25 mg IV and a normal saline 500-mL bolus were administered. Symptoms resolved within 15 minutes, and then the remainder of dose 2 was administered over 45 minutes without further incident. Dose 3 was administered over 90 minutes without premedication; however, 8 minutes into the infusion, the patient again experienced abdominal and back pain (grade 2). Diphenhydramine 50 mg IV was administered, and the symptoms resolved. The remainder of the infusion was administered over 60 minutes. Dose 4 was infused over 90 minutes without incident after diphenhydramine premedication. The patient responded to ipilimumab and is under active observation.

Patient 3.

A 73-year-old-man with unresectable locally advanced melanoma of the right lower extremity, psoriatic arthritis, hypothyroidism, and myelodysplastic syndrome received dose 1 of ipilimumab without incident. Twenty minutes into dose 2, the patient reported pruritus and a mild maculopapular rash (grade 2). He denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or throat tightness. Oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Diphenhydramine 25 mg IV gave rapid symptom relief. The remainder of the infusion was administered over 10 minutes without further incident. Doses 3 and 4 were each administered over 90 minutes with premedication (diphenhydramine 50 mg IV) without incident. The patient experienced disease stabilization and is on active observation.

Patient 4.

A 36-year-old woman with metastatic melanoma tolerated the first dose without incident. Six minutes into dose 2, she experienced coughing and facial flushing (grade 2). Ipilimumab infusion was stopped. She denied shortness of breath, chest pain, or throat tightness. Oxygen saturation was 99% on room air. She received diphenhydramine 25 mg IV, and after 15 minutes, her symptoms resolved. The remainder of the infusion was administered over 90 minutes. She received dose 3 with premedication (diphenhydramine 25 mg IV) infused over 90 minutes without incidence. After dose 3, she developed bloody diarrhea felt to be ipilimumab-induced colitis, and dose 4 was withheld.

Patient 5.

A 62-year-old woman with locally advanced mucosal melanoma arising from the cervix tolerated dose 1 without incident. Fifteen minutes into dose 2, the patient complained of chest/back pain and shortness of breath (grade 3). Ipilimumab infusion was stopped. Oxygen saturation was 84% on room air, although she denied having throat tightness. Hydrocortisone 100 mg IV and diphenhydramine 25 mg IV were administered, and 4 L of oxygen was delivered via nasal cannula. Oxygen saturation improved to 98%, and symptoms began to resolve within 10 minutes. Electrocardiogram revealed new T-wave inversions. Aspirin 325 mg was given. After 20 minutes, symptoms had resolved, and oxygen saturation was 100% on room air. Patient was transported to the emergency room for further evaluation. She was not rechallenged with the remainder of dose 2. Cardiac work-up was negative, and she was discharged from the emergency room. At dose 3, patient received premedication (diphenhydramine 50 mg IV and dexamethasone 20 mg IV) and ipilimumab infused over 90 minutes without incident. Her course was complicated by ipilimumab-induced colitis, and dose 4 was withheld.

Patient 6.

A 71-year-old man with metastatic melanoma to the brain, lungs, and soft tissue received dose 1 without incident. Immediately after dose 2, he began to experience shaking chills and rigors. Meperidine 25 mg IV was administered with resolution of symptoms. Doses 3 and 4 were given with diphenhydramine 25 mg IV premedication over 90 minutes without incident.

Patient 7.

A 58-year-old man with metastatic uveal melanoma to the lung, liver, peritoneum, and lymph nodes tolerated dose 1 without incident. Thirty minutes after completion of dose 2 of ipilimumab, he began to experience chills and rigors (grade 2). Vital signs were stable. The patient received diphenhydramine 25 mg IV and meperidine 25 mg IV with resolution of symptoms. The patient received dose 3 with diphenhydramine 50 mg oral premedication and dose 4 without premedication. Both were infused over 30 minutes and were well tolerated.

Subsequent Doses of Ipilimumab After IRRs

All seven patients received subsequent doses of ipilimumab, which were administered over 30 to 90 minutes. Five patients received premedication and tolerated dose 3 without incident. Two patients did not receive premedication, and one these patients experienced an IRR at dose 3. That same patient received dose 4 with premedication without incident. Although premedication with diphenhydramine seems to be important for subsequent ipilimumab treatment after an IRR, it is unclear from our experience whether the infusion rate needs to be slowed down.

DISCUSSION

IRRs are common during infusions of monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab (77%), trastuzumab (40%), and cetuximab (12% to 19%).6 IRRs are most commonly associated with symptoms of flushing, chills, pruritus, rash, nausea, dyspnea, cough, bronchospasm, fever, malaise, headache, hypotension/hypertension, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and pain.6 IRRs typically occur during the infusion or hours after completion of the infusion and vary depending on the infusional agent. IRRs caused by monoclonal antibodies have been noted to occur primarily with the first or second infusions.6–8

The pathophysiology of IRRs caused by monoclonal antibodies is not entirely defined but seems to be a result of cytokine release syndrome or a hypersensitivity (immunoglobulin E–mediated) reaction.6,9,10 For rituximab (anti-CD20), IRRs may be caused by the release of cytokines elicited when rituximab binds to CD20 and causes cell lysis.6 Cetuximab (anti–epidermal growth factor receptor) was found to express a glycolytic epitope (galactose-α-1,3-galactose) that is recognized by pre-existing antibodies in patients.10 Management of mild to moderate IRRs caused by monoclonal antibodies usually involves slowing the rate of infusion. For more severe IRRs, medical therapy with epinephrine, antihistamines, corticosteroids, oxygen, bronchodilators, and vasopressors has been effective.6

Although the mechanism of IRRs for ipilimumab has not been formally studied, 1.1% of 1,024 evaluable patients tested positive for binding antibodies against ipilimumab in an in vitro immunoassay.11 The clinical validity of this assay is in question, however, because none of these patients were noted to have IRRs to ipilimumab.

Because of concern for IRRs, it is common to recommend longer infusion times for novel monoclonal antibodies. However, as investigators accumulate more experience with the individual antibody, it has been found that shorter infusions times are feasible and safe.12–14 This results in more efficient use of infusion facilities and greater patient convenience.

In the case of ipilimumab, the 90-minute infusion time was initially selected as a conservative guideline but not based on any specific data of which we are aware. Now with extensive experience with the drug, we are in a position to reassess this guideline. Our data show that the incidence of IRRs for the 3 and 10 mg/kg doses at 90 minutes was low (2.2% and 4.3%, respectively) and not statistically different. This led to a change in our institutional guidelines to infuse standard-dose ipilimumab over 30 minutes because a shorter infusion time would be more convenient for patients and more cost effective for the institution. In the first 120 patients treated with 3 mg/kg infused over 30 minutes, the incidence of IRR was 5.8%, and the few reactions seen all occurred at dose 2. Two of the seven IRRs did not occur during the infusion. One IRR occurred immediately after the completion of infusion, and the second IRR occurred 30 minutes after the end of infusion, suggesting that it is may be reasonable to observe patients for a short period of time after the infusion. The finding that IRRs at dose 1 are uncommon suggests that, in most patients experiencing an IRR, the first dose is a sensitizing dose.

The incidence of IRRs in patients receiving 30-minute infusions was acceptably low; although slightly higher than for the standard 90-minute infusions, this difference did not quite reach statistical significance (P = .06). An important point is that six of seven IRRs were grade 2, and in no case was the IRR dose limiting. IRRs should be managed according to institutional guidelines for hypersensitivity reactions, which may include discontinuation of infusion and administration of appropriate rescue medications including antihistamines and corticosteroids. With appropriate premedication (diphenhydramine and/or corticosteroids), subsequent infusions after an IRR seem to be safe. It is unclear from our data whether subsequent infusions after an IRR need to be administered more slowly. This shorter infusion time enhances patient convenience and allows more efficient use of outpatient infusion facilities.

Acknowledgment

We thank Leonard Saltz, MD, chairman of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee, for several insightful discussions and encouragement to improve our institutional guidelines for ipilimumab infusions. We acknowledge the help of Nicole Kelly and Joyce Guillen in collecting and collating data.

Glossary Terms

- monoclonal antibody:

an antibody that is secreted from a single clone of an antibody-forming cell. Large quantities of monoclonal antibodies are produced from hybridomas, which are produced by fusing single antibody-forming cells to tumor cells. The process is initiated with initial immunization against a particular antigen, stimulating the production of antibodies targeted to different epitopes of the antigen. Antibody-forming cells are subsequently isolated from the spleen. By fusing each antibody-forming cell to tumor cells, hybridomas can each be generated with a different specificity and targeted against a different epitope of the antigen.

Appendix

Table A1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Melanoma Treated Retrospectively With 10 mg/kg and 3 mg/kg of Ipilimumab Infused Over 90 Minutes

| Characteristic | No. of Patients |

|

|---|---|---|

| Ipilimumab 3 mg/kg (n = 440) | Ipilimumab 10 mg/kg (n = 103) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 276 | 67 |

| Female | 164 | 36 |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 69 | 65 |

| Range | 21-97 | 33-87 |

| Stage of cutaneous melanoma at treatment start | 378 | 97 |

| II | 1 | 0 |

| IIIB | 3 | 4 |

| IIIC | 19 | 13 |

| IV | 355 | 80 |

| Ballantyne stage of mucosal melanoma at treatment start | 36 | 2 |

| I | 1 | 0 |

| II | 4 | 0 |

| III | 31 | 2 |

| Stage of ocular melanoma at treatment start | 26 | 4 |

| IV | 26 | 4 |

| Known brain metastasis at treatment start | ||

| Yes | 45 | 27 |

| No | 395 | 76 |

| Previous treatments | ||

| None | 422 | 15 |

| Chemotherapy | 15 | 72 |

| Interleukin-2 | 1 | 10 |

| High-dose interferon | 1 | 15 |

| BRAF inhibitor | 3 | 3 |

| Total ipilimumab doses received per patient | ||

| 1 dose | 34 | 12 |

| 2 doses | 54 | 15 |

| 3 doses | 63 | 14 |

| 4 doses | 233 | 17 |

| > 4 doses | 56 | 45 |

Footnotes

Supported in part by the John K. Figge Fund (P.B.C.).

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Paul B. Chapman

Collection and assembly of data: Parisa Momtaz, Vivian Park, Paul B. Chapman

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Safety of Infusing Ipilimumab Over 30 Minutes

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Parisa Momtaz

No relationship to disclose

Vivian Park

No relationship to disclose

Katherine S. Panageas

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AztraZeneca

Michael A. Postow

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bioconnections LLC, FirstWord, Millennium Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Margaret Callahan

Employment: Bristol-Myers Squibb (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Kiowa Hakko Kiran

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Jedd D. Wolchok

Honoraria: EMD Serono, Janssen Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, MedImmune, Ziopharm, Polynoma, Polaris, Jounce, GlaxoSmithKline, Potenza Therapeutics, Vesuvius Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), MedImmune (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: I am a co-inventor on an issued patent for DNA vaccines for treatment of cancer in companion animals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Paul B. Chapman

Honoraria: Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech/Roche, Provectus, Momenta Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech/Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Provectus, Momenta Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech/Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Bristol-Myers Squibb

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber J, Hamid O, Amin A, et al. Randomized phase I pharmacokinetic study of ipilimumab with or without one of two different chemotherapy regimens in patients with untreated advanced melanoma. Cancer Immun. 2013;13:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber JS, O'Day S, Urba W, et al. Phase I/II study of ipilimumab for patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5950–5956. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf.

- 6.Chung CH. Managing premedications and the risk for reactions to infusional monoclonal antibody therapy. Oncologist. 2008;13:725–732. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cersosimo RJ. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of cancer, Part 2. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:1631–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cersosimo RJ. Monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of cancer, Part 1. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:1531–1548. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/60.15.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dillman RO. Infusion reactions associated with the therapeutic use of monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of malignancy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1999;18:465–471. doi: 10.1023/a:1006341717398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CH, Mirakhur B, Chan E, et al. Cetuximab-induced anaphylaxis and IgE specific for galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1109–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bristol-Myers Squibb. YERVOY (ipilimumab) [US package insert] Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reidy DL, Chung KY, Timoney JP, et al. Bevacizumab 5 mg/kg can be infused safely over 10 minutes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2691–2695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritchard CH, Greenwald MW, Kremer JM, et al. Safety of infusing rituximab at a more rapid rate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Results from the RATE-RA study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribas A, Chesney JA, Gordon MS, et al. Safety profile and pharmacokinetic analyses of the anti-CTLA4 antibody tremelimumab administered as a one hour infusion. J Transl Med. 2012;10:236. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]