Abstract

Patient: Female, 36

Final Diagnosis: Mediastinal cystic hygroma

Symptoms: Chest discomfort

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Pulmonology

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Lymphangioma is an atypical non-malignant, lymphatic lesion that is congenital in origin. Lymphangioma is most frequently observed in the head and neck, but can occur at any location in the body. About 65% of lymphangiomas are apparent at birth, while 80–90% are diagnosed by two years of age. Occurrence in adults is rare, as evidenced by less than 100 cases of adult lymphangiomas reported in the literature.

Case report:

A 36-year-old Indian woman with a medical history of recurrent pleural effusions presented with chief complaints of dyspnea on exertion for one year and a low-grade fever for one month. A thorax CT revealed left-sided pleural effusion with thin internal septations. Thoracoscopy revealed a large cystic lesion arising from the mediastinum from the hilum surrounding the mediastinal great vessels. The diagnosis of lymphangioma was confirmed via histopathologic examination of the cyst. It was managed with partial cystectomy along with the use of a sclerosing agent (talc).

Conclusions:

The size and location of lymphangiomas can vary, with some patients presenting with serious problems like respiratory distress, while others may be asymptomatic. Complete cyst resection is the gold standard treatment for mediastinal cystic lymphangioma. Partial cyst resection along with the use of sclerosing agents can be an effective option when complete cystectomy is not possible. Although lymphangioma is a rare patient condition, it should be included in the differentials for patients presenting with pleural effusions. Also, a biopsy should be done at the earliest opportunity to differentiate lymphangioma from other mediastinal malignant tumors.

MeSH Keywords: Cystectomy; Lymphangioma, Cystic; Pleural Effusion; Talc; Thoracoscopy

Background

Lymphangioma is an atypical, benign, lymphatic lesion that is congenital in origin. It is most frequently observed in the head and neck, but can occur at any location in the body. Other sites involved include the axilla, thoracic wall, groin, retroperitoneum (omentum, pancreas, and adrenals), pharynx, and mediastinum [1–3]. Amongst the mediastinal tumors, lymphangioma constitutes 0.7–4.5% [4]. About 65% of lymphangiomas are apparent at birth while 80–90% are diagnosed by two years of age [5]. Occurrence in adults is rare, as evidenced by less than 100 cases of adult lymphangioma reported in the literature [6] making mediastinal lymphangioma a rare condition (<1%). Higher prevalence of lymphangioma is seen in patients with chromosomal abnormalities like Downs syndrome, Turners syndrome, Edward syndrome, and Patau syndrome. They arise due to congenital malformations in the connection of lymphatics with the venous system, or due to abnormal growth of the lymphatic tissue leading to blockage of the lymphatic channels. This then leads to fluid accumulation in these spaces which results in the formation of lymphangioma [4]. A lymphangioma can be capillary, cystic, or cavernous depending on the tissue surrounding it. Ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the current imaging modalities used for its diagnosis. Complete surgical resection is the gold standard treatment while alternative treatment with sclerosing agents can be used in some scenarios. Here we present an unusual case of an adult Indian female with recurrent pleural effusions of unknown etiology that we later diagnosed as lymphangioma.

Case Report

A 36-year-old female Indian patient with a past medical history of recurrent pleural effusions presented to the outpatient clinic at Getwell Hospital and Research Institute, India, with the chief complaint of dyspnea on exertion for one year, and low-grade fever for one month. Her previous records revealed that she was diagnosed as a case of recurrent non-resolving pleural effusion. The pleural fluid had been aspirated on two occasions. Tuberculosis being a common cause of pleural effusion in this part of the world, an anti-tuberculosis treatment was empirically started before she presented to us. The patient was on anti-tuberculosis drugs for three months, without relief of symptoms, along with recurring pleural effusion. Her medications included isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. The patient was referred to our hospital since she had recurring pleural effusion despite receiving anti-tuberculosis treatment.

On history, she denied having a cough, sputum, or weight loss. A review of systems was otherwise negative. Her past medical and surgical histories were non-contributory. Her personal history was negative for smoking and alcohol. Her social, occupational, and family history was not significant. On examination, the vitals were within normal limits except for a mild fever (101.5°F, 38.6°C) and increased respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. On examination of the respiratory system, stony dullness to percussion, decreased breath sounds on auscultation, decreased vocal resonance, and fremitus on the left side of the chest while the right side was within normal limits. Neurologic, cardiac, and abdominal examination revealed no abnormalities.

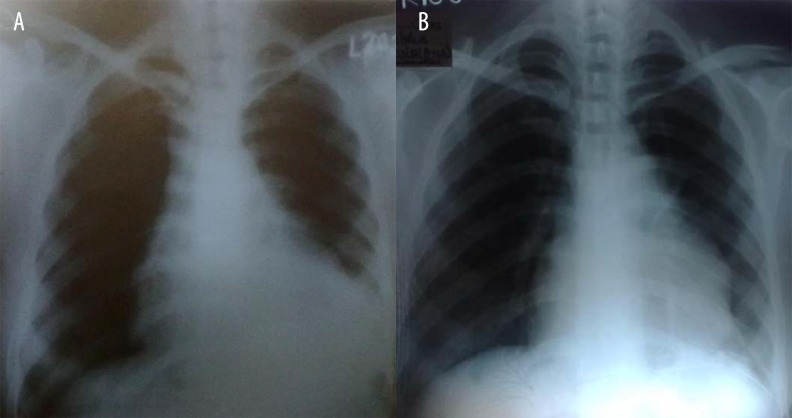

Chest x-ray posterior anterior view showed homogenous opacity in the left side with signs of pleural effusion (Figure 1). CT thorax revealed left-sided pleural effusion with thin internal septations (Figures 2, 3). Routine laboratory investigations like CBC, serum BUN, and serum creatinine were within normal limits except for a rise in ESR of 30 mm/hour. Screening for HIV and HBsAg was negative. The differentials included tubercular effusion, soft tissue tumor, bronchogenic cyst, pericardial cyst, and lymphangioma. The bronchoscopy samples were negative for bacterial culture, including tuberculosis and cell cytology. Thoracoscopy was done with an aim to aid the diagnosis and obtain a pleural fluid sample for laboratory analysis. During the procedure, a large cystic lesion was visualized arising from the mediastinum from the medial part of the hilum surrounding the mediastinal great vessels. When the cyst was incised, and its interior was visualized, no infection or inflammation was observed. The appearance of the cyst suggested a congenital cyst. The cyst was present close to the great vessels which made complete excision difficult. Hence, a partial excision of the cyst (deroofing) was done. The biopsy samples of the cyst were sent for histopathological examination. The pleural fluid was drained and sent for laboratory analysis. A chest tube was placed to drain the fluid. The patient was stable after the procedure. Collection of fluid from the drain continued to be more than 500 mL per day even after six days post-thoracoscopy.

Figure 1.

Chest x-ray illustrating the left-sided pleural effusion on initial presentation of the patient.

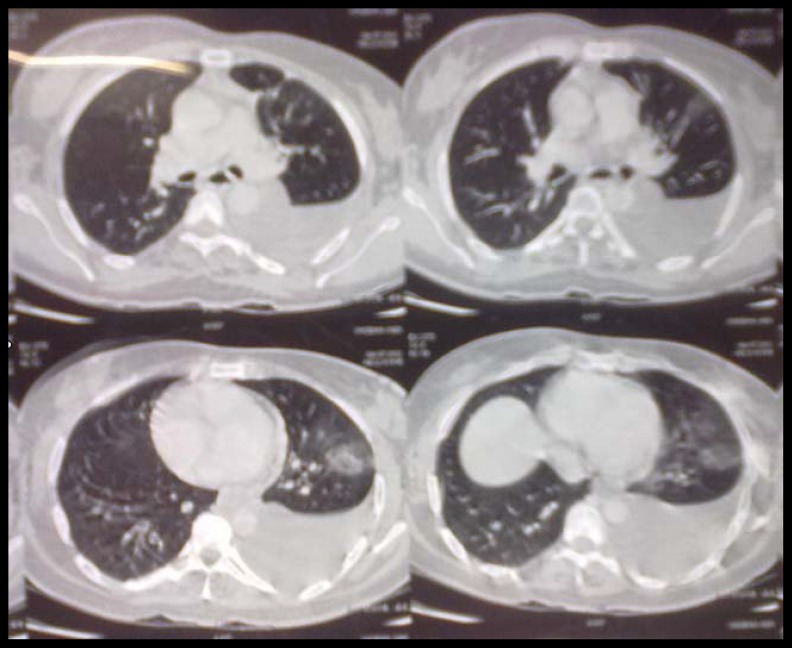

Figure 2.

Thorax CT illustrating the left-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 3.

Thorax CT depicting the encysted left-sided effusion.

Pleural fluid analysis results were as follows: cloudy appearance, pH of 7.25, specific gravity 1.050, protein content 6 grams, WBC 1500/mm3 with lymphocytic predominance, glucose 45 mg/dL, LDH 489 IU/L, and adenosine deaminase was negative. The pleural fluid microscopic examination, culture, and cytological results were negative. Histopathological examination of the thoracoscopic biopsy sample showed features consistent with benign lymphatic cyst or lymphangioma. Hence, the diagnosis of mediastinal lymphangioma was established.

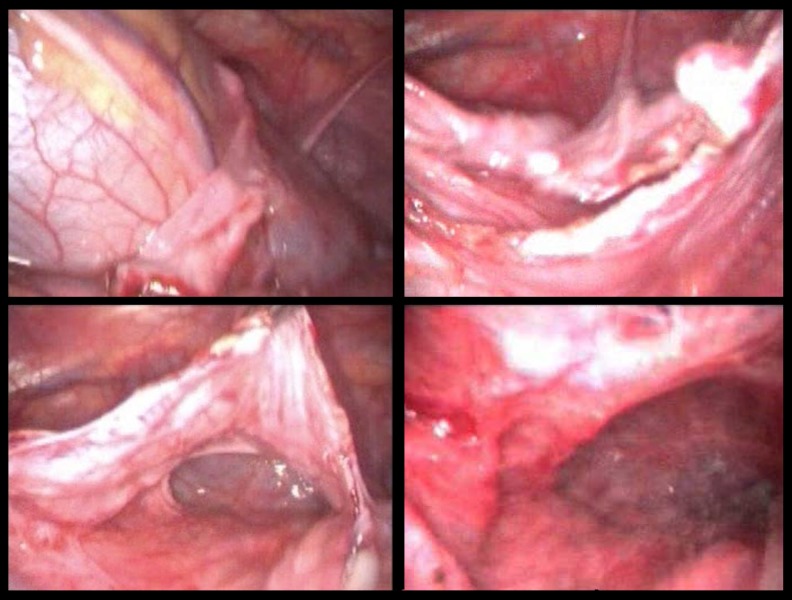

To manage the persistent secretion of fluid, a repeat thoracoscopy was done with talc insufflation (Figure 4) in the remnant of the cyst, and a chest drain was placed. The patient was stable postoperatively. There were no complications. The anti-tubercular drugs were stopped. The patient was then discharged two days later with a drain in situ. A chest x-ray was taken before the patient was discharged (Figure 5A). The proper care of the drain was explained to the patient. After one week follow-up, the intercostal drain collection decreased to less than 50 mL per day and was removed. The patient has been symptom-free since discharge and her chest x-ray shows complete resolution of the left-sided pleural effusion. She had a follow-up chest x-ray after an interval of two months to check for any signs of recurrence (Figure 5B). The patient comes for regular medical follow-up, and no recurrence of the cyst has been seen over the past year.

Figure 4.

Thoracoscopic partial cystectomy and talc poudrage of the cyst wall.

Figure 5.

Chest x-rays showing gradual improvement of the pleural effusion postoperatively.

Discussion

Cystic lymphangioma, first described by Wernher in 1843, is a rare congenital entity due to lymphatic malformations. Lymphangiomas are of three types: capillary, cystic, and cavernous [7]. Capillary lymphangiomas are dilatations of capillary-sized lymphatic vessels that are connected to a normal lymphatic network. The cavernous variant contains dilated lymphatic sinuses in an actively growing lymphoid stroma, which are also connected to a normal lymphatic network. Cystic lymphangiomas are characterized by multiple, large cyst-like spaces lined with flat endothelial cells that may be empty or filled with clear proteinaceous or chylous fluid containing lymphocytes and sometimes red blood cells. Less than 1% of lymphangiomas occur in the mediastinum [8,9]. The most common location of lymphangiomas are in the head and neck area (unlike the adult case presented here) and they are more common in females [4].The present case is rare in its presentation in terms of its location in the mediastinum.

Most lymphangiomas are diagnosed in children and 90% of cases are diagnosed by two years of age. A study of 37 cases with lymphangioma, with patients in the age group 8 years to 77 years (mean age of 45 years), found that of the 37 cases, 33 (89%) had the lymphangioma located in the mediastinum, similar to the location of the lymphangioma of our patient. The mean age of 45 years was much higher than the age of our patient (36 years).

Pathogenesis of lymphangioma occurs during the embryonic development of the lymphatics when there is a lack of connection between the primitive lymph sac and rest of the lymphatic system. As a result, the cisterns arising from this lymph sac are separated from the normal functioning lymphatics [11]. An acquired variant of lymphangioma can occur in patients due to chronic obstruction of the lymphatics. This is seen more commonly in middle-aged patients with a history of surgery, those undergoing radiation therapies for malignancy, and those suffering from a chronic infection. The fact that in older adults lymphangiomas are found in the posterior or middle mediastinum and are purely liquid cysts suggest an acquired origin. Lymphangiomas can be seen in cases of chromosomal abnormalities such as Turner syndrome, Down syndrome, and trisomy 13 and 18 abnormalities.

Lymphangiomas are hemodynamically inactive, mature tumors with a low potential for carcinogenesis. Most of them are asymptomatic [8], unlike our patient who presented with progressive dyspnea. Symptomatic patients are often found to have large lesions. The symptomatic manifestation can be variable. Dyspnea and respiratory distress are the most common symptoms that occur when the lymphangioma compresses the tracheobronchial tree, pharynx, or phrenic nerve, or presents as pleural effusion [12] as in the present case. Compression of the esophagus can lead to dysphagia. It can also cause hoarseness via recurrent laryngeal nerve compression [15]. In children, lymphangioma can present with feeding, speech, and respiratory difficulties. The presentation can be acute when the lymphangioma bleeds or ruptures, particularly in patients with retroperitoneal lymphangioma in adrenals or pancreas [2,3].

Teratomas, bronchogenic cysts, and pericardial cysts can have a similar presentation to cystic lymphangioma. Also, malignant tumors like thymomas, neuroblastomas, thyroid carcinomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and lymphomas can have a similar presentation. Most lymphangiomas are diagnosed incidentally, as in the present case. Although there is no described case of malignant transformation of a cystic lymphangioma, a biopsy is essential to rule out the differentials.

The definitive treatment is complete surgical resection of the cyst. Complete resection may occasionally be difficult because of the lymphangia’s close proximity to vital structures. In such cases, marsupialization, injection of sclerosing agents, steroids, diathermy, and radiotherapy are generally ineffective and may lead to hemorrhage and infection. OK-432 seems beneficial in extra-thoracic lymphangioma [13]. The scenario in our present case included involvement of the neurovascular bundles, so a decision to proceed with a partial cystectomy was made.

Sclerosing agents that induce inflammation such as bleomycin, ethanol, sodium tetradecyl sulfate, and doxycycline have been used for lymphangioma therapy [13]. The induced inflammation results in the fibrosis of the cyst. A new sclerosing agent OK-432 (an inactive strain of group A Streptococcus pyogenes) has shown promising results in the treatment of large unilocular cystic lymphangioma [14]. However, its efficacy with small cysts is poor [15]. Bleomycin is a poor candidate as it causes pulmonary fibrosis and has resulted in many adverse drug events in several studies [16,17]. In our case, we used video-assisted thoracoscopic talc insufflation as it has been approved by the FDA and European countries for use in nonmalignant pleural effusions. Talc is extremely safe and has no long-term detrimental effects, making it safe in young, healthy individuals who have no lung impairment, fibrosis, or increased likelihood of cancer or mortality [18–20]. Although the use of sclerosing agents is a minimal invasive procedure, it can cause minor complications such as inflammation and infections. None of these complications were seen in our patient after administration of sclerosing agents.

Conclusions

We present a case of a patient with lymphangioma with an unusual presentation of recurrent pleural effusion. We know that the size and location of lymphangiomas can vary, and some patients can have symptoms such as respiratory distress, while other patients can be asymptomatic. Thus, each patient should be evaluated individually and treated accordingly. This case study demonstrated that thoracoscopy can be effectively used to diagnose lymphangiomas located in the mediastinum. While complete cyst resection is the gold standard treatment for lymphangioma, complete surgical resection is difficult under certain circumstances when the cyst infiltrates the mediastinum, displacing the mediastinal structures, or if it envelopes the neurovascular bundles or great vessels. In such cases, partial cyst resection along with the use of sclerosing agents can be used as a possible treatment. Although lymphangioma is a rare patient condition, it should be included in the differentials for patients presenting with pleural effusions.

References:

- 1.Bossert T, Gummert JF, Mohr FW. Giant cystic lymphangioma of the mediastinum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:340. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(01)01096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayashi J, Yamashita Y, Kakegawa T, et al. A case of cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas. J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:372–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02358380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iderne A, Duchene H, Bruant P. Cystic lymphangioma of the adrenal gland. J Chir (Paris) 1995;132:87–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaffer K, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Patz EF, Jr, et al. Thoracic lymphangioma in adults: CT and MR imaging features. Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:283–89. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.2.8310910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saleiro S, Magalhães A, Moura CS, Hespanhol V. Linfangioma cístico do mediastino. Rev Port Pneumol. 2006;12(6):731–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naidu SI, McCalla MR. Review Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck in adults: A case report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):218–22. doi: 10.1177/000348940411300309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khobta N, Tomasini P, Trousse D, et al. Solitary cystic mediastinal lymphangioma. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(127):91–93. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson C, Askin FB, Heitmiller RF. Solitary pulmonary lymphangioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(4):1337–38. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamagishi S, Koizumi K, Hirata T, et al. Experience of thoracoscopic extirpation of intrapulmonary lymphangioma. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;53(6):313–16. doi: 10.1007/s11748-005-0135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riquet M, Briere J, Le Pimpec-Barthes F, et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the neck and mediastinum. Rev Mal Respir. 1999;16(1):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94(5):473–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1976.tb05134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robie DK, Gursoy MH, Pokorny WJ. Mediastinal tumors – airway obstruction and management. Sem Pediatr Surg. 1994;3:259–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acevedo JL, Shah RK, Brietzke SE. Nonsurgical therapies for lymphangiomas: A systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138(4):418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler JS, Morreau P, Mahadevan M, Pease P. OK-432 and lymphatic malformations in children: the Starship Children’s Hospital experience. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(10):855–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters DA, Courtemanche DJ, Heran MK, et al. Treatment of cystic lymphatic vascular malformations with OK-432 sclerotherapy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(6):1441–46. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000239503.10964.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niramis R, Watanatittan S, Rattanasuwan T. Treatment of cystic hygroma by intralesional bleomycin injection: Experience in 70 patients. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20(3):178–82. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sainsbury DC, Kessell G, Fall AJ, et al. Intralesional bleomycin injection treatment for vascular birthmarks: A 5-year experience at a single United Kingdom unit. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):2031–44. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820e923c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cardillo G, Carleo F, Giunti R, et al. Videothoracoscopic talc poudrage in primary spontaneous pneumothorax: A single-institution experience in 861 cases. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;15(1):81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noppen M. Who’s still afraid of talc? Eur Respir J. 2007;29(4):619–21. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00001507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt I, Barber B, Southon R, Treasure T. Is talc pleurodesis safe for young patients following primary spontaneous pneumothorax? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6(1):117–20. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2006.147546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]