Abstract

Background: Identifying the transition from relapsing-remitting to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) can be challenging for clinicians. Little previous research has explored how professionals experience working with patients during this specific stage of the disease. We explored the experiences of a group of multidisciplinary professionals who support patients in the transition to SPMS to describe this stage from a professional perspective.

Methods: This qualitative semistructured interview study included 11 professionals (medical, nursing, and allied health professionals; specialists and generalists) working with patients with MS in South Wales, United Kingdom. Thematic analysis of the interview data was performed.

Results: Two overarching themes were identified: the transition and providing support. The transition theme comprised issues related to recognizing and communicating about SPMS. Uncertainty influenced recognizing the transition and knowing how to discuss it with patients. The providing support theme included descriptions of challenging aspects of patient care, providing support for caregivers, using the multidisciplinary team, and working within service constraints. Providing adequate psychological support and engaging patients with self-management approaches were seen as particularly challenging.

Conclusions: Caring for patients in the transition to SPMS generates specific challenges for professionals. Further research on health-care interactions and patients'/professionals' experiences regarding the transition phase may help identify strategies for professional development and learning and how to optimize the patient experience at this difficult stage of disease.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling neurologic condition affecting young adults,1 but little research to date has specifically examined professionals' experiences of identifying and managing the transition to secondary progressive MS (SPMS). Most patients are diagnosed as having relapsing-remitting disease, but as time progresses, most will transition to SPMS.1 Secondary progressive MS is defined retrospectively once a sustained period of worsening neurologic impairment has been established over at least 6 to 12 months.2 However, applying this diagnosis in clinical practice is challenging and often results in a period of diagnostic uncertainty.3 Sand and colleagues3 showed that the time taken from clinicians' first recording the possibility of progression to actually definitively labeling SPMS was, on average, nearly 3 years. Professionals can interpret disease progression as a personal defeat for which they feel responsible.4 No biological markers or imaging methods are available to definitively predict disease course,5 which may result in true diagnostic uncertainty.3 Discussing this uncertainty with patients takes clinicians' time and emotional energy.6 In the United Kingdom it is recommended that disease-modifying agents be stopped once established nonrelapsing progressive disease is confirmed.7 Confirming the transition and stopping disease-modifying agents may also result in the patient being reviewed less frequently by a neurologist and being transferred to nurse-led rather than neurologist-led follow-up. Clinicians' awareness of these issues and the potential resultant patient anxiety may act as a further barrier to timely discussion.3

We aimed to explore in depth the experiences of specialists and generalists working with patients in the transition stage. We were interested in how clinicians addressed the transition with their patients and how they provided support throughout this phase. Because self-management strategies are advocated for people with MS dealing with the impact of their symptoms,8 we also explored how professionals currently promoted self-management. Data exploring patient and caregiver perspectives of the transition to SPMS are reported elsewhere.9 The aim was to inform future research and development of strategies for professional development and learning to optimize the patient experience at this difficult stage of disease.

Methods

Participants

The advisory group members developed a sampling frame based on their experience with multidisciplinary team involvement in patient care during the transition phase. We planned to interview three MS specialist nurses, two neurologists, and one of each of the following professionals: occupational therapist, physiotherapist, neuropsychologist, general practitioner, community nurse, and social worker. MS specialist nurses and neurologists represented nearly half of the proposed sample due to regularly working with patients in the transition and their depth of experience in the area. All the professionals were recruited from South Wales, United Kingdom (enabling face-to-face interviews), across three different University Health Board areas offering neurology services. Professionals working locally in the previously mentioned roles were identified using contacts of the advisory group members. There was a limited pool of potential participants from certain professional groups in the local area, making it inevitable that many of the participants would be known to the advisory group members, but this sampling approach enabled rapid recruitment and generated a good participation response. Participants were made aware that the study was commissioned by an MS charity and that results would be anonymized before reporting. Participants were aware of the researcher's (FD) background as a university-based academic general practitioner. No participants were known to the researcher before involvement in the study. We recognized that being interviewed by a fellow health professional might facilitate or inhibit certain participant responses.10

Setting

The participants all work in South Wales. Multiple sclerosis services in this area are provided by the publicly funded National Health Service. Secondary care services are led by consultant neurologists, and all patients have access to advice and support from a secondary-care–based MS specialist nurse. Patients also have access to allied health professionals who may operate specialist or generalist services. Community services, including general practitioners (primary-care physicians), community nurses (for people requiring nursing care at home), and social workers, also contribute to care provision. These community providers may not have any specialist knowledge of MS.

Data Collection

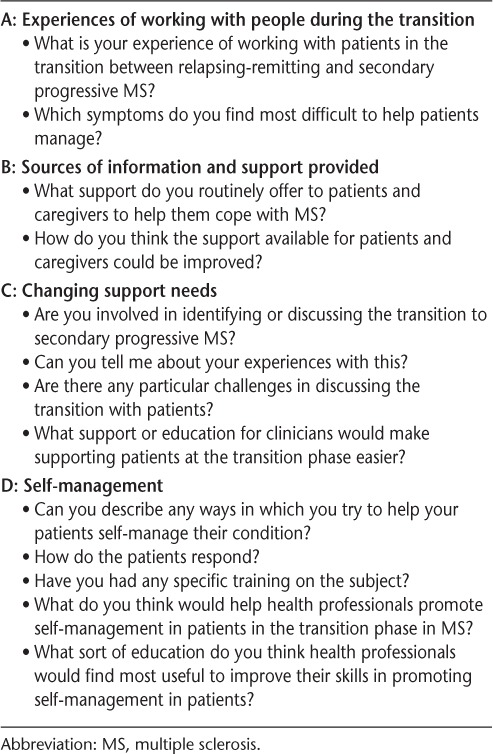

The project was approved by the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 01. Qualitative semistructured interviews were conducted with health professionals to explore their experiences of working with people in the transition to SPMS.11 The semistructured interview guide (summarized in Table 1) was developed iteratively with input from members of the multidisciplinary study advisory group, which included a patient representative. The questions were developed through discussion and based on the advisory group members' experience and knowledge of the existing literature. All the participants provided written informed consent. Interviews were performed by one of us (FD) in a quiet room at the professionals' workplaces.

Table 1.

Interview guide summary

Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers. Transcripts were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke.12 After data immersion, a codebook was generated by one of us (FD), and codes were applied to the transcripts using NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Victoria, Australia). Once all the interview transcripts were coded, one of us (FD) began the process of identifying candidate themes, which were then discussed with another author (FW) (who was also familiar with the data) and subsequently refined. The findings from the preliminary data analysis were also summarized and circulated to the participants by e-mail for comment and validation. This exercise suggested that the emerging findings were credible to the participants. The data were reviewed by one of us (FD) to ensure that the refined themes were representative, and the themes were named collaboratively (FD and FW). The researchers have differing professional backgrounds (FD as a clinician and FW as a social scientist) and brought their differing perspectives to the analysis. The sample size was too small to reach theoretical saturation in each professional group, although there was consensus across the differing groups on many of the issues discussed.

Results

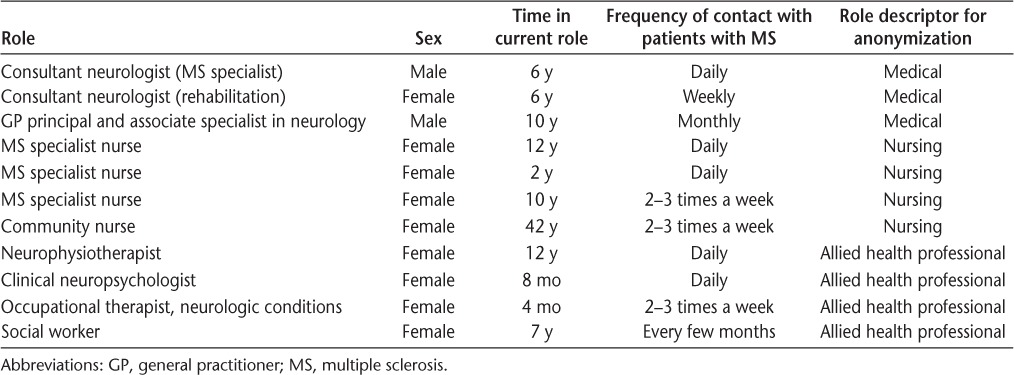

Three professionals did not respond to the e-mail invitation, so alternative participants were approached. Ten participants were recruited via e-mail. One further professional was recruited via an invitation from another participant. The participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. Interviews lasted between 20 and 52 minutes.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participating health professionals

Two overarching themes were identified: the transition and providing support. The themes and associated subthemes are shown in Table 3, together with the initial open codes to which they relate. Illustrative quotations are provided throughout the “Results” section. To help maintain anonymity for the respondents, quotations are labeled as coming from one of three subgroups: medical, nursing, or allied health professional. Participants are numbered according to the order in which they were interviewed.

Table 3.

Themes, subthemes, and associated initial open codes (from which the themes were derived)

Theme 1: The Transition

Recognition

The transition to SPMS is a retrospective diagnosis, and this meant that recognizing the transition took time and often required repeated assessments: “It takes a while to know for definite if they are in transition” (participant 6; nursing professional). Professionals described that continuity of care helped them feel more confident about reaching the diagnosis. Conversely, the lack of an objective test could cause uncertainty that resulted in a tendency to delay discussion: “That's part of our anxiety, I think, about the uncertainty because we can't stick them in the MRI scanner and have a result from [the radiologist] saying this person is now progressive” (participant 2; medical professional).

When faced with possible diagnostic error, clinicians usually waited for the situation to evolve before confirming SPMS. One clinician described giving patients the “benefit of the doubt” (participant 7; medical professional) in this situation before considering discontinuing disease-modifying medication. Clinicians recognized that the uncertainty of the situation could be difficult for their patients and that accepting disease progression was sometimes challenging for clinicians themselves. Some professionals shared their uncertainty about prognosis with their patients, whereas others dealt with the uncertainty by deferring the discussion.

Although diagnosing the transition was seen as the role of neurologists and specialist nurses, the allied health professionals described that if they felt that patients' disease course had changed, they would encourage patients to reflect on their own situations and come to their own conclusions: “Those sorts of decisions are best discussed, made with a consultant, saying you are secondary […] [we] perhaps try and sort of plant the seed a bit. So I'd maybe say to a patient, ‘Well, listen, 2 years ago, you could walk for an hour at a time, now you're only walking for 10 minutes, do you think things have changed?’” (participant 1; allied health professional).

There were differing views about how equipped patients were to interpret their own changing symptoms. Some participants suggested that although patients might recognize deterioration of their symptoms, they did not always have the necessary knowledge to interpret this deterioration as a sign of the transition and required professional support to understand the meaning of the changes they experienced: “I think patients don't understand necessarily that relapsing-remitting MS is likely to change into secondary progressive MS” (participant 8; nursing professional). Others suggested that patients probably knew “deep down” that their MS was worsening but were not ready to accept this and that this denial prevented full recognition of the transition.

Communication

Broaching the Subject. Professionals described the value of having an open dialogue about SPMS with patients as an important move away from the medical paternalism of the past. They recognized that discussing SPMS in a timely manner allowed their patients to prepare for their future. However, despite recognizing the importance of this open communication, initiating the conversation remained challenging. Professionals reported that patients rarely raised the subject of the transition themselves, so professionals struggled to know when they should tackle the issue: “It is very difficult when someone is relapsing to talk the sort of doom and gloom, what might happen to you however many years down the line because MS is so unpredictable isn't it, you can't be certain what's going to happen to them” (participant 2; medical professional).

Professionals felt that it was probably inappropriate to discuss SPMS soon after diagnosis, when it may be of limited current relevance to patients, but equally felt that when the transition was imminent it was probably too late. There was an overall feeling that some patients were left unprepared for the possibility of secondary progression: “Because we don't prepare them. [interviewer: No?] Not until we are asked by them mostly. [interviewer: Yeah, yeah if they do that.] Yeah if they bring it up. I wouldn't necessarily sit down and say ‘alright, you know 4 months now after your relapse, we keep an eye on this because possibly you are getting secondary’” (participant 6; nursing professional).

When professionals did feel it was appropriate to broach the subject, finding a way to communicate the news empathically could be stressful: “It's trying to word it without frightening them, like the booklets [say], ‘they accumulate disability slowly over time,’ well that sounds good, but not when you're trying to tell someone that” (participant 5; nursing professional). Generally, professionals described more difficulties with raising the topic themselves, whereas responding to patients' queries or concerns was seen as much easier. Professionals also described that patients' interest in receiving information about their condition could be highly variable: “Some people need lots, some people don't want any, some people really don't want to know but […] you have to tailor it to the individuals I think” (participant 9; medical professional).

Dealing with the Response. The emotional impact of the confirmation of SPMS weighed heavily on the minds of practitioners, making the discussion sometimes more difficult. A spectrum of different coping reactions to SPMS was recognized, from acceptance as a natural progression to triggering a significant emotional response: “What I see in clinic is, like, a shrug of the shoulders or, it is what it is, so there's kind of that resignation to that” (participant 4; allied health professional). Specialists recognized that when patients were already dealing with increasing disability, discontinuation of treatment was difficult to manage, especially because they felt it could lead to a sense of abandonment among their patients. Denial, panic, and a sense of loss were other frequently encountered reactions.

Strategies Used. Professionals described how continuity of care allowed them to get to know their patients and to better judge how and when to provide information. Warning shots and hints were sometimes used to try to raise awareness of the possibility of transition when professionals became suspicious that it might be happening. To counter the worst-case scenario thinking that patients often expressed after hearing their disease course had changed, the professionals described trying to frame the transition to SPMS in a positive light. They tried to emphasize the possibility that decline of function might be very slow and focused on the support services available. A few described taking a proactive approach, finding it easier to discuss the possibility of transition routinely before it became relevant as a way of raising awareness of the potential for the disease course to change: “I talk about the stopping criteria even if they are nowhere near it so that they understand that progressive disease may well come along in the future” (participant 7; medical professional).

Some professionals explained how their working practices had facilitated a more open approach to discussing SPMS. One nurse described using a preclinic questionnaire (which included a question about a perceived worsening of symptoms not related to relapses) that patients completed as a way of opening the conversation about current disease stage. The practice of sending patients copies of clinic letters also made clinicians more mindful of ensuring that the content did not come as a surprise to patients. Written information was recognized as extremely useful for patients, although participants did not routinely provide literature about the transition. Often this was due to a lack of suitable resources available at hand, although even if resources were available, sometimes professionals felt it was the wrong moment at which to provide potentially upsetting information.

Theme 2: Providing Support

In addition to the difficulties surrounding identifying and discussing the transition, professionals described additional clinical and organizational challenges throughout the transition phase.

Challenging Aspects of Patient Care

Most professionals were involved to some extent in symptom management, with some symptoms described as more difficult to manage than others. In general, invisible symptoms, such as changes in mood, memory, and personality, were seen as more challenging because professionals often felt that they lacked the necessary skills and resources to manage these effectively: “I don't have that expertise. I can try and take them through some initial sort of steps and suggestions, but at the end of the day I'm not a trained counselor” (participant 8; nursing professional). Professionals recognized that often their own ability to provide adequate psychological support was limited and were then further frustrated that there was limited provision for more formal psychological support in the health-care system. Recognition of the wider social impact of cognitive symptoms increased the professionals' dissatisfaction with what they were able to offer: “What has such a significant impact on social relationships and everything else is the cognitive side of things, so people find it very distressing when, okay, physical adaptations can be made in the work environment to sustain employment; however, when you start noticing yourself that you're just not able to do things the way that you could before, that becomes very, very distressing” (participant 4; allied health professional).

Although symptoms such as spasticity and fatigue could also be very difficult, clinicians preferred dealing with situations in which there was an opportunity for them to feel that they were doing something active: “If you offer them a tablet, then somehow that helps you feel better at least” (participant 7; medical professional). Staff often expressed frustration with the challenge of promoting patient engagement, perceiving that the advice they provided was sometimes met with apathy or resistance: “Some people you can sort of keep on about things, you need to do this, and you need to do this, and it is like hitting a brick wall” (participant 1; allied health professional).

Patients' difficulties with low mood, cognition, and fatigue were all recognized as barriers to effective self-management. Professionals generally agreed that self-management did not appeal to all patients. It was difficult to encourage these patients to take control themselves rather than to defer the responsibility to the professionals. Some described that although they felt that they should do more to encourage self-management, they sometimes instinctively tried to help patients by doing things for them instead: “I think a bit like a doctor, writing a prescription you feel you want to do something for somebody and it is not always the right thing […] I probably ought to signpost people more instead of doing it all myself” (participant 3; allied health professional). Professionals often described that once they had provided the patient with the required information, it became the patient's choice how they used this information: “You know we can give them all the tools but if they are not motivated for whatever reasons they are, no, you know it's not going to help them” (participant 6; nursing professional).

Professionals often seemed to lack specific strategies to help support self-management in more challenging situations. When self-management did work well, professionals observed that it could help patients feel in control while discouraging excessive reliance on professional support. Concerns about patients receiving too much upsetting information could lead health professionals to discourage certain activities, such as joining support groups, although they had also seen some patients benefit from sharing their experiences with others. Although none of the professionals interviewed had received any specific self-management support training, most viewed it as a natural part of patient care: “That's the whole philosophy, really. You need to try and work in partnership with a person and let them make the decisions, as long as they've got the capacity” (participant 10; allied health professional).

Supporting Caregivers

Professionals recognized the important role of caregivers and the burden associated with being a caregiver: “My whole attitude with all family members is that if they're not supported, it doesn't work” (participant 11; nursing professional). Professionals described caregivers' reluctance to request support for themselves and reported that in some cases, caregivers actively resisted support. Support for caregivers was often largely described as services such as respite care and “sitting,” which would not become necessary until caregivers were taking on a greater role in providing physical care. Providing the other types of practical and emotional support that might be more important regarding the transition phase seemed to require either a direct request from the caregiver or for the professional to detect difficulties if caregivers happened to attend patients' routine appointments. Although professionals tried to identify caregivers' difficulties whenever possible, they recognized with some frustration that even if problems were identified there was a limited amount that they could actually offer due to limited resources: “Well, we always ask how they're managing at home and if they're coping, but that's about it” (participant 5; nursing professional).

Working with Others

Multidisciplinary working was important to all the professionals interviewed. The valuable expertise that colleagues could provide was recognized as beneficial to both professionals and patients: “I don't think you can do it on your own. If it's just me in a clinic on my own it wouldn't work. I need the nursing staff and the [occupational therapist] and the physio[therapist]” (participant 2; medical professional). Referrals to other members of the team seemed to occur for different reasons. Professionals described recognizing the limitations of their own expertise and feeling that the input of others would improve patient care. There were also suggestions that limited time and workload pressures could prompt professionals to delegate to others rather than taking personal responsibility for certain elements of patient care.

Service Constraints

Professionals wanted to be able to provide more services but were limited in what they could achieve due to time and service constraints. Having the time to develop a relationship with their patients improved the support professionals felt they could offer, but large workloads acted as barriers: “The caseloads are too big to give people enough time and attention” (participant 10; allied health professional). Professionals felt that having more time available would facilitate continuity of care and allow some patients' difficulties to be preempted. This more continuous model of care was suggested as a way to ensure that patients received the right help at the right time, potentially avoiding patients reaching crisis points before seeking support. Early SPMS was suggested as the right time to target patients for more intensive follow-up and support. However, it was recognized that individual support needs and preferences varied widely. Professionals aspired to see services tailored to incorporate more elements of choice and flexibility to meet individuals' personal requirements.

Discussion

This exploratory work described the experiences of the transition from the perspectives of a small group of multidisciplinary health professionals who regularly work with people with MS and their caregivers. The transition can be identified only over time. Professionals often felt unsure about when first to mention SPMS and recognized that they might be leaving their patients unprepared. Apprehension about discussing the transition was described because of the potential for a negative reaction. Managing invisible symptoms and providing adequate psychological support were ongoing challenges, especially within the constraints of the service described.

Strengths and Limitations

A range of different professionals involved in patient care were included in the study, and considerable variation in attitudes and in current practices toward addressing the transition with patients was identified. The qualitative approach supported a more in-depth understanding of the complexity of working at this stage than would have been possible using a quantitative method. Although confirming the transition was generally a concern for neurologists and MS nurses, the other themes were well represented across the specialist and generalist participants. Data analysis was performed collaboratively, and participant validation suggested that the emerging themes had strong credibility. All the participants worked in a single geographic area, and we recognize that the challenges described may be specific to the local context. The small sample may have resulted in a failure to capture the full range of varying viewpoints that exist. Additional data from each professional group would have also allowed the relative importance placed on different issues to be assessed.

Putting the Findings into Context

The challenges that the participants described regarding confidently identifying the transition to SPMS seem to be reflected in previous quantitative research, suggesting that the confirmation of SPMS can take several years.3 Bamer et al.5 found that people with MS were more likely to classify themselves as progressive compared with physician evaluators. Our complementary qualitative research showed that some patients felt that they had transitioned to SPMS without the issue having been directly discussed at a consultation.9 In other settings, as in this study, clinician discomfort with delivering negative or uncertain diagnoses and prognoses has been described.13,14 This discomfort may decrease the clarity of information clinicians provide to patients.15 Consultation observations have shown that neurologists do not regularly assess patients' preferences for information provision around the time of diagnosis.16 The medical model of care predominated in the way participants in this study addressed the issue of the transition with their patients, with some professionals describing making decisions on their patient's behalf about when they might be ready to take on information. In other cases, professionals seemed to wait for patients to ask questions rather than initiating the discussion themselves. People with MS have described that they do not want to be protected from troubling possibilities.17 It may be that some patients would prefer to be kept fully informed regarding the transition but that professionals are not sufficiently recognizing this desire. From a professional perspective it seems that deferring the discussion is used to improve diagnostic certainty and help facilitate a gradual recognition of changing symptoms in their patients. However, for patients who are experiencing changing symptoms, this may add to the confusion and uncertainty regarding how SPMS is diagnosed and what it means for them as an individual.9 Our work exploring the transition to SPMS from the patient perspective showed that people with MS wanted clarification of what having SPMS meant for them, reassurance about how they would be supported by the health-care team, and self-help information.9 A move to a more proactive patient-centered model of care whereby information needs are actively assessed and addressed might improve transition care, although this still represents a major culture shift for some professionals.

The challenges of managing invisible symptoms, such as cognitive impairment and fatigue, and of providing psychosocial support identified in these interviews have also been described elsewhere.18,19 Patients' psychological well-being and fatigue are also recognized barriers to engaging with self-management approaches. Future continuing professional development activities for professionals working with patients in the transition to SPMS could include training in psychological techniques that promote positive coping, which has been trialed with some success elsewhere.20,21 Supporting self-management in this patient group is challenging, and professionals may need help to develop advanced facilitation skills.

The development of new biomarkers22 and clearer diagnostic criteria for the transition to SPMS may in the future help alleviate some clinician uncertainty about whether the label of SPMS should be confirmed. However, the challenges of dealing with the emotional impact of the transition will remain. Further research across a range of settings and with greater numbers of participants from each professional group is required to understand whether the challenges described herein are common to health professionals working elsewhere. Although much research has explored how to improve communication in the diagnostic stage,23 the transition to SPMS has previously been largely overlooked. Our research suggests that it may be important to further explore how and when clinicians choose to broach the subject of SPMS and how this can be better facilitated given both the variation in practice and the difficulties that professionals described. Gathering data about patients' perspectives on their preferences regarding discussing disease progression could helpfully inform health professionals. Exploring how differing working practices and service delivery models might facilitate or inhibit the provision of high-quality care during the transition would also be useful to inform service design.

Conclusion

The transition to SPMS is a diagnostic challenge for professionals, which, in turn, makes communicating with patients at this time difficult. Some professionals felt that they lacked all of the skills that could be useful in supporting patients through the transition, particularly in relation to psychological support and self-management. Although multidisciplinary working provides great support for professionals, they remain frustrated by service constraints. The present data suggest that health-care interactions and patients'/professionals' experiences regarding the transition to SPMS should be researched further as a basis for identifying strategies for professional development and learning and how to optimize patient outcomes and experiences at this difficult stage of disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the interview participants; Tracy Nicolson, Rebecca Pearce, Gayle Sheppard, and Barbara Stensland for their contributions as members of the study advisory group; and the MS Trust, and the National Institute for Health Research, through the Comprehensive Clinical Research Network, for their support.

PracticePoints

Professionals may feel reluctant to initiate discussions about secondary progressive disease and may defer the conversation because of uncertainty about the stage of disease and how to discuss the transition.

Routinely discussing the possibility of progression or asking patients to perform self-assessments of their own condition may facilitate this discussion.

Providing psychological support and promoting self-management are important but are hard to achieve. Increasing professionals' training in these areas may improve future patient care.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the MS Trust (grant 505859).

References

- 1. Murray TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple sclerosis. BMJ. 2006; 332: 525– 527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rovaris M, Confavreux C, Furlan R, Kappos L, Comi G, Filippi M. Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: current knowledge and future challenges. Lancet Neurol. 2006; 5: 343– 354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sand IK, Krieger S, Farrell C, Miller AE. Diagnostic uncertainty during the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014; 20: 1654– 1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Golla H, Galushko M, Pfaff H, Voltz R. Unmet needs of severely affected multiple sclerosis patients: the health professionals' view. Palliat Med. 2012; 26: 139– 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bamer AM, Cetin K, Amtmann D, Bowen JD, Johnson KL. Comparing a self report questionnaire with physician assessment for determining multiple sclerosis clinical disease course: a validation study. Mult Scler. 2007; 13: 1033– 1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holloway RG, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology. 2013; 80: 764– 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scolding N, Barnes D, Cader S, et al. Association of British Neurologists: revised (2015) guidelines for prescribing disease-modifying treatments in multiple sclerosis. Pract Neurol. 2015; 15: 273– 279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fraser R, Ehde D, Amtmann D, et al. Self-management for people with multiple sclerosis: report from the first international consensus conference, November 15, 2010. Int J MS Care. 2013; 15: 99– 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davies F, Edwards A, Brain K, et al. “You are just left to get on with it”: patient and carer experiences of the transition to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. BMJ Open. 2015; 5e007674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chew-Graham CA, May CR, Perry MS. Qualitative research and the problem of judgement: lessons from interviewing fellow professionals. Fam Pract. 2002; 19: 285– 289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pope C, van Royen P, Baker R. Qualitative methods in research on healthcare quality. Qual Saf Health Care. 2002; 11: 148– 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006; 3: 77– 101. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell AJ. Reluctance to disclose difficult diagnoses: a narrative review comparing communication by psychiatrists and oncologists. Support Care Cancer. 2007; 15: 819– 828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaduszkiewicz H, Bachmann C, van den Bussche H. Telling “the truth” in dementia: do attitude and approach of general practitioners and specialists differ? Patient Educ Couns. 2008; 70: 220– 226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fallowfield LJ, Jenkins VA, Beveridge HA. Truth may hurt but deceit hurts more: communication in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2002; 16: 297– 303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pietrolongo E, Giordano A, Kleinefeld M, et al. Decision-making in multiple sclerosis consultations in Italy: third observer and patient assessments. PLoS One. 2013; 8: e60721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thorne S, Con A, McGuinness L, McPherson G, Harris SR. Health care communication issues in multiple sclerosis: an interpretive description. Qual Health Res. 2004; 14: 5– 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartung H-P, Matthews V, Ross AP, Pitschnau-Michel D, Thalheim C, Ward-Abel N. Disparities in nursing of multiple sclerosis patients: results of a European nurse survey. Eur Neurol Rev. 2011; 6: 106– 109. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Turner AP, Martin C, Williams RM, et al. Exploring educational needs of multiple sclerosis care providers: results of a care-provider survey. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2006; 43: 25– 34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mjaaland TA, Finset A. Communication skills training for general practitioners to promote patient coping: the GRIP approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2009; 76: 84– 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stensrud TL, Gulbrandsen P, Mjaaland TA, Skretting S, Finset A. Improving communication in general practice when mental health issues appear: piloting a set of six evidence-based skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2014; 95: 69– 75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dickens AM, Larkin JR, Griffin JL, et al. A type 2 biomarker separates relapsing-remitting from secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2014; 83: 1492– 1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Solari A. Effective communication at the point of multiple sclerosis diagnosis. Mult Scler. 2014; 20: 397– 402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]