CME/CNE Information

Activity Available Online:

To access the article, post-test, and evaluation online, go to http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Target Audience:

The target audience for this activity is physicians, physician assistants, nursing professionals, and other health-care providers involved in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Learning Objectives:

Appropriately apply information learned in this activity to assign a severity grade to MS patients

Recognize the limitations of the severity grading scheme and be able to address those limitations in both treating and educating patients

Accreditation Statement:

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the accreditation requirements and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC), Nurse Practitioner Alternatives (NPA), and Delaware Media Group. The CMSC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The CMSC designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Nurse Practitioner Alternatives (NPA) is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation.

NPA designates this enduring material for 1.0 Continuing Nursing Education credit (none of these credits are in the area of pharmacology).

Disclosures:

Francois Bethoux, MD, Editor in Chief of the International Journal of MS Care (IJMSC), has served as Physician Planner for this activity. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Robert Charlson, MD, has served on an advisory board for Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Joshua Herbert, BA, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Ilya Kister, MD, has served as a consultant for Biogen Idec and Genentech. Dr. Kister has also performed contracted research for Bayer, Genzyme, and Biogen Idec.

Laurie Scudder, DNP, NP, has served as Nurse Planner for this activity. She has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The anonymous peer reviewers for the IJMSC have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

The staff at the CMSC, NPA, and Delaware Media Group who are in a position to influence content have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Method of Participation:

Release Date: October 1, 2016

Valid for Credit Through: October 1, 2017

In order to receive CME/CNE credit, participants must:

Review the CME/CNE information, including learning objectives and author disclosures.

Study the educational content.

Complete the post-test and evaluation, which are available at http://www.cmscscholar.org.

Statements of Credit are awarded upon successful completion of the post-test with a passing score of >70% and the evaluation.

There is no fee to participate in this activity.

Disclosure of Unlabeled Use:

This CME/CNE activity may contain discussion of published and/or investigational uses of agents that are not approved by the FDA. CMSC, NPA, and Delaware Media Group do not recommend the use of any agent outside of the labeled indications. The opinions expressed in the educational activity are those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent the views of CMSC, NPA, or Delaware Media Group.

Disclaimer:

Participants have an implied responsibility to use the newly acquired information to enhance patient outcomes and their own professional development. The information presented in this activity is not meant to serve as a guideline for patient management. Any medications, diagnostic procedures, or treatments discussed in this publication should not be used by clinicians or other health-care professionals without first evaluating their patients' conditions, considering possible contraindications or risks, reviewing any applicable manufacturer's product information, and comparing any therapeutic approach with the recommendations of other authorities.

Abstract

Currently used classification schemes for multiple sclerosis (MS) have not taken into account disease severity, instead focusing on disease phenotype (ie, relapsing vs. progressive). In this article, we argue that disease severity adds a crucial dimension to the clinical picture and may help guide treatment decisions. We outline a practical, easy-to-implement, and comprehensive scheme for severity grading in MS put forward by our mentor, Professor Joseph Herbert. We believe that severity grading may help to better prognosticate individual disease course, formulate and test rational treatment algorithms, and enhance research efforts in MS.

Currently, multiple sclerosis (MS) is divided into several subtypes according to clinical course (relapsing vs. progressive) and disease activity (eg, new magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] lesions) without regard to disease severity (how quickly a patient accumulates disability). The most recent phenotype-based MS classification jettisons traditional severity modifiers (ie, benign or malignant MS)1 and does not take into account other potentially important factors (ie, recovery from relapses, response to medications, etc.). Although phenotypes unquestionably provide critical information directly affecting treatment decisions, we argue herein that information regarding disease severity adds an important dimension to the clinical picture and should supplement phenotypic description in clinical practice and trial design.

The main argument against severity modifiers is that the “severity and activity of [MS] can change significantly and unpredictably.”1(p282) This critique is valid. Studies have shown that approximately half of all patients labeled with benign MS after 10 years of disease will no longer be considered benign after another 10 to 20 years of follow-up.2,3 However, in our view, this should not lead to abandoning the concept of benign MS but to its modification. Disease benignity should not be regarded as an immutable trait but as a prognostic factor: earlier benign disease predicted long-term benign disease with 50% certainty. (Another problem with the traditional concept of benign MS, as used here, is that it is based on ambulation-based disability measures; its utility has been called into question, as it does not take into account “invisible disability”—cognitive impairment, fatigue, and depression.) More accurate prognosis could result from combining severity with other readily available clinical variables, such as age, disease duration, and disease course, in a prediction algorithm, as we demonstrate in a later section.

In addition to its prognostic utility, a disease severity metric provides a useful framework for the discussion of treatment options. For example, knowledge that a patient's course has thus far been severe or aggressive may be an important factor to consider when making a treatment decision. The severity grade could be incorporated into treatment algorithms in conjunction with other factors—disease type, age, comorbidities, MRI parameters, and individual treatment preferences. Severity measures could also be useful for clinical trials, as a guide to patient selection (eg, only severely affected patients would be considered for higher-risk interventions such as bone marrow transplant) as well as an outcome measure (ie, change in severity score could be assessed before and after the intervention4).

Severity classification is not a novel concept in medicine. From prenatal heart disease to systemic sclerosis to colon cancer, disease severity measures allow for patient comparisons and influence treatment decisions.5–7 The New York Heart Association functional classification, for example, provides a simple clinical tool to assess the severity of heart failure and guide interventions.8 In recent years, it has also been used to design clinical trials and measure outcomes.9 Severity classification in MS presents specific problems in view of the disease's notoriously variable course. We outline a practical and comprehensive schema for severity grading in MS put forth a decade ago by our late mentor, Professor Joseph Herbert.10

Herbert's Six Severity Grades

The idea underlying Herbert's proposal was to define disease severity not in absolute terms—by a set disability threshold reached within a specified time (ie, malignant MS is the “use of a cane or worse after 2 years of disease”11)—but in relative terms (ie, how an individual's disability compares with others' with similar disease duration). Such an approach allows for a nuanced stratification that can be applied to any patient with any disability at any point in the disease course rather than to subsets of patients on the extreme ends of the severity spectrum after a prespecified disease duration.

Herbert's severity grading is based on the concept of the Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score (MSSS) introduced by Roxburgh et al.12 The MSSS is a disease duration–adjusted disability rank score, explained in more detail in Figure 1. The disability rank score can be conceptualized as an approximation of the prevalence (frequency) of Expanded Disability Status Scale(EDSS) scores in the reference cohort of patients with the same disease duration. Thus, a patient with an MSSS of 1.7 is as much or more disabled than approximately 17% of patients with the same disease duration. An approximation of rank with prevalence improves the closer the spacing between disability strata gets (Figure 1).

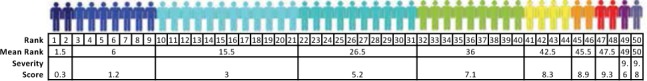

Figure 1.

Illustration of the concept of the Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score, a disease duration–adjusted disability score

Each color represents an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score. This hypothetical reference population of 50 patients with disease duration of x years has been lined up in order of increasing EDSS scores: two patients have EDSS scores of 0 (dark blue), ranked 1 and 2; seven have EDSS scores of 1 (blue), ranked 3 to 9; 12 have EDSS scores of 2 (cyan), ranked 10 to 21; ten have EDSS scores of 3 (turquoise), ranked 22 to 31; nine have EDSS scores of 4 (green), ranked 32 to 40; four have EDSS scores of 5 (yellow), ranked 41 to 44; two have EDSS scores of 6 (orange), ranked 45 and 46; two have EDSS scores of 7 (red), ranked 47 and 48; one has an EDSS score of 8 (purple), ranked 49; and one has an EDSS score of 9 (indigo), ranked 50. Severity score is the normalized mean rank, which is computed by taking the mean rank for each score divided by the total cohort count +1 and then multiplied by 10. For example, in the reference population, the severity score for the EDSS of 4 for patients with disease duration of 5 years would be 10×mean(32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40)/50+1 = 360/51 = 7.1.

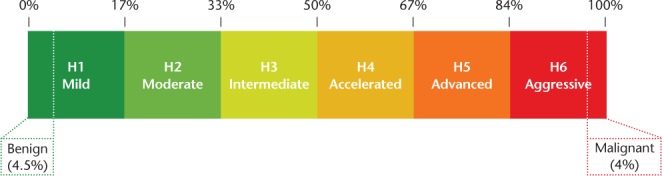

Herbert divided patients with MS into six approximately equipopulated tiers of disability based on their MSSS (Figure 2). Patients with an MSSS less than 1.7 (ie, the least disabled sextile) would be classified as having mild MS; patients with an MSSS of 1.7 to less than 3.4, moderate MS; patients with an MSSS of 3.4 to less than 5.0, intermediate MS; MSSS of 5.0 to less than 6.7, accelerated MS; MSSS of 6.7 to less than 8.3, advanced MS; and the most disabled sextile, MSSS greater than 8.3, aggressive MS. For simplicity, we label these as grades H1 to H6. In addition, Herbert suggested a rigorous MSSS-based definition for the two well-entrenched but variably defined terms benign and malignant MS, with benign defined as an MSSS less than 0.45 and malignant as greater than 9.6 (Figure 2).13,14

Figure 2.

Herbert's six severity grades: H1 to H6

Herbert's severity grading divides patients with multiple sclerosis into six approximately equipopulated tiers of disability based on their Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score.

Although the division of patients into six tiers of disability has not yet been validated for stability over time, it does agree with several previous attempts to classify the extremes of disability (see the next section on aggressive MS). Herbert's severity grading affords an intuitive, easy-to-understand assessment of a patient's disease on the spectrum of MS severity and provides a useful framework for the discussion of treatment approaches. Severity classification also lends itself to the testing of prognostic algorithms in MS.15 Moreover, it can be used as a research tool to compare disease course in different subpopulations, as in the demonstration of an accelerated rate of disability progression in African-American individuals,16 or different time epochs.

An important limitation of this severity grading is the requirement of an EDSS assessment, which can be made only by a specially trained examiner and is not always correctly performed in practice (eg, patients are often not walked 500 m as required for the EDSS). This largely limits the application of MSSS-based classification to specialty MS clinics and clinical trials. To circumvent this problem, Herbert et al. introduced the Patient-derived MSSS (P-MSSS), which is a ranking of Patient-Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale scores rather than clinician-rated EDSS scores.17 The P-MSSS stands in the same relation to the PDDS scale as the MSSS does to the EDSS. Previous work by our group and others18,19 has shown a strong correlation between the PDDS scale and the EDSS. A six-tiered classification using the P-MSSS, exactly analogous to an MSSS-based classification, could readily be implemented in any clinical setting and could find wide applicability. The P-MSSS has shown its utility in studies comparing the self-referred North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS) Registry with MS clinic populations20; in the assessment of the effects of a specific variable (ie, body mass index) on disease severity; and in the development of a risk calculator of severe disease.15

Other limitations of the severity-based system need to be acknowledged. First, disease onset may be uncertain in some patients. If a patient is unable to recognize or recall the inaugural symptoms of MS, the severity grade will be inaccurate. Most patients are diagnosed in their 20s and 30s, when the possibility of significant errors in timing of onset is unlikely, but the possibility of error may not be negligible in the apparently older-onset patients. An additional caveat relates to assigning severity grade in the setting of relapses. In view of the instability of disability measures during and following a relapse, we recommend that severity grade determination not be made within 6 months of a relapse. Furthermore, given the high degree of variability of the MSSS during the first year of disease,12 it may be preferable to avoid using severity grades obtained within 1 year of symptom onset in prognostic algorithms.

Severity grade, such as the MSSS, has been validated as a predictive tool at the cohort level but not in individual patients. Thus, severity grade should not be considered in isolation but in the context of the broader clinical picture and in conjunction with other determinants of disease prognosis. Herbert suggested that severity grade could be communicated in conjunction with other key clinical data (age, sex, disease onset, phenotype, and disability). Such a quick and efficient way of presenting key clinical data was inspired by the gravida/para/abortus shorthand that is universally adopted by obstetricians. A clinic note that starts off with a standard notation—for example, “37 yo woman/onset 5 years/active, relapsing (phenotype)/advanced/H4(severity grade)”—succinctly communicates a wealth of data about the clinical picture. In the future, such descriptions could be supplemented by validated radiographic, serologic, and genomic markers. As communicating disease severity has the potential to cause negative psychological effects (especially regarding the aggressive and malignant MS designations), clinicians need to exercise discretion in discussing disease severity with patients. In some instances, information about disease severity could be relayed indirectly without mention of a specific grade, and may help a patient to better understand the rationale for a proposed treatment plan.

Herbert's Definition of Aggressive MS

There is no consensus on how to define severe MS, but it is well established from observational studies that a small minority of patients with MS follow a rapidly disabling disease course.11,21 Many terms have been proposed for this phenomenon—malignant MS, aggressive MS, catastrophic MS, fulminant MS—with a seemingly equal number of definitions, both qualitative and quantitative.22–24

The lack of consensus likely stems from the difficulty of applying a uniform definition of severe MS to patients in different stages of the disease, as can be illustrated with the following examples. One patient is a woman who is wheelchair-bound, but able to transfer, after 15 years with MS; the other patient is a young man who requires a cane 2 years after MS onset. Both patients have considerable disability. Do either of these patients have aggressive MS? Clearly, this depends on the definition. Previous attempts at defining aggressive disease were often difficult to apply in practice because they relied on a fixed number of attacks over a set period or on a certain disability threshold after a specified number of years.

Herbert's definition of aggressive MS, on the other hand, can be applied to patients with any disease duration and any disability level. The starting point of the definition is a choice of coordinates on the MSSS table that correspond to an EDSS score of 6.0 (obligatory use of cane to walk 100 m) after 7 years of disease onset, which is consistent with the original definition of severe MS set forth by Poser et al.11 This set of EDSS score/disease duration coordinates yields an MSSS cutoff value of 8.24 and predicts the prevalence of aggressive MS to be approximately 17.5%, or one-sixth of the MS population, corresponding to grade H6.

Herbert's severity grading is, thus, free of predetermined cutoff values for either EDSS score or disease duration. For the previous example, the woman in the wheelchair at 15 years' duration has an MSSS of 8.17 (in our system, H5, or advanced MS), and the man using a cane after 2 years has an MSSS of 9.59 (H6, or aggressive MS). This example emphasizes the importance of placing disability in the context of disease duration. Although in absolute terms the second patient's disability (cane) is less than that of the first (wheelchair), the pace of disease in the second patient is relatively more rapid than in the first patient.

Some patients accrue disability at an exceptionally fast rate; Herbert proposed to designate this subset of patients with aggressive MS as having malignant MS. This subgroup is defined by an MSSS of 9.6 or greater, which corresponds to an EDSS score of 6.0 or worse after 2 years of disease onset. This group comprises approximately 4% of the MS population. Again, this definition of malignant MS is disease duration invariant, and clinicians can stratify patients into the malignant MS subgroup as early as 1 year after disease onset. The young man in the example would, therefore, be characterized as having malignant MS, which may have implications for how clinicians view his case and approach treatment.

The potential utility of Herbert's severity grading in an increasingly complex therapeutic landscape is apparent. Patients with aggressive MS should be considered for early initiation of the most aggressive, high-risk treatment options (ie, monoclonal antibodies, chemotherapies, and even allogeneic stem cell transplant). Additional factors other than disease severity—age, whether the patient has relapses, MRI activity, and so on—must also be taken into account when making treatment decisions. Yet by rigorously defining patients with aggressive disease in terms of MSSS or P-MSSS grades, clinicians can rapidly identify patients who may be in need of above-average treatment aggressiveness very early in the disease course. This is especially important in view of the concept of a window of therapeutic opportunity,25 which posits that treatments are most effective when given at an earlier stage before irreversible disability thresholds have been reached.

Herbert's definition of aggressive MS can be incorporated as an inclusion criterion in trials of high-risk treatments as well. This would allow for a more homogenous population selection across study arms. Severity grade could also be used as an outcome measure (ie, measuring the percentage of patients in each arm that “exited” from the most severe grade into milder grades or vice versa). The utility of the MSSS as an outcome measure has recently been illustrated in a reanalysis of data from a pivotal natalizumab trial, which showed a significantly greater effect for natalizumab-treated patients with highly active disease compared with more traditional first-line treatments.4 Similar reanalyses of other studies, such as the recent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation efforts, may prove equally instructive.

Predicting Aggressive MS

One application of Herbert's severity grading has been in the development of a risk calculator for predicting aggressive MS by Kister et al.15 We took as a starting point the definition of aggressive MS as the group of patients with P-MSSSs greater than 0.83 (this would correspond to the most disabled sextile in Herbert's grading, H6). Data from a large self-report registry, NARCOMS, were gathered, including disease duration, self-reported disability, age, and sex. At baseline, patients were stratified into six groups based on disease severity (grades H1–H6). The contribution of each baseline group to those ultimately found to have aggressive MS 2 years later was then calculated, and a logistic regression model was developed and validated using only sex, age, and baseline P-MSSSs to estimate that probability. The risk calculator was found to be sensitive and specific for predicting severe disease 2 years after baseline.

The proposed risk calculator provides a simple tool to predict the development of aggressive MS. As an example, consider a 37-year-old woman with a 7-year disease duration and a PDDS scale score of 2 (“no limitations in gait, but significant problems from MS that limit her in other ways”). The risk calculator predicts a 2% chance of advancing to the severe MS group 2 years later. Another patient, a woman with a PDDS scale score of 4 (“early use of a cane”) and a 7-year disease duration, on the other hand, has a 21% chance of aggressive MS within 2 years. Validated prognostic models using Herbert's disease severity classification can help make discussions of future disability much more evidence based and can provide patients and clinicians with valuable information for guiding treatment decisions.

Summary

Herbert's severity grading scheme allows physicians to efficiently stratify patients with MS according to their relative disease severity. The severity metric adds a dimension to the clinical picture that is absent in the phenotype-based classification. The concept of relative disease is intuitive and easy to communicate to other clinicians involved in the patient's care, as well as to the patient himself or herself (when appropriate). The classification system could use either clinician- or patient-derived ranking, with the latter (P-MSSS based) having the advantage of wider applicability. Severity grade, in conjunction with other key clinical and paraclinical characteristics, could help inform prognosis, as well as the formulation and testing of rational treatment algorithms in which intensity of treatment is linked to disease severity. Future work should be directed toward validating severity grade–based prognostic algorithms in clinical and research settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The PDDS scale and P-MSSS table have been included as Supplementary Appendix 1 (232.8KB, pdf) and Supplementary Appendix 2 (232.8KB, pdf) (published in the online version of this article at ijmsc.org). The PDDS scale is provided for use by the NARCOMS Registry (http://www.narcoms.org/pdds). NARCOMS is supported in part by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC) and the CMSC Foundation. The P-MSSS table is reproduced with permission from Kister et al.17

PracticePoints

The concept of disease severity grading can inform treatment decision making, research efforts, and patients' understanding of their disease status.

The proposed severity grading system for MS allows physicians to easily stratify patients with MS by relative disease severity using clinician-rated (the Expanded Disability Status Scale) or patient-rated (the Patient-Determined Disease Steps) disability scales.

The proposed severity grading system needs to be validated in clinical and research settings.

Footnotes

Dedication: This article is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Joseph Herbert, a consummate physician, an innovative researcher, a generous mentor, a founder of two large MS centers, and a remarkably courageous man. He is greatly missed.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Charlson has served on an advisory board for Teva Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Kister has served as a consultant for Biogen Idec and Genentech. Dr. Kister has also performed contracted research for Bayer, Genzyme, and Biogen Idec. Mr. Herbert has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Lublin FD, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: the 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014; 83: 278– 285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawkins SA, McDonnell GV. Benign multiple sclerosis? clinical course, long term follow up, and assessment of prognostic factors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999; 67: 148– 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sayao A, Devonshire V, Tremlett H. Longitudinal follow up of “benign” multiple sclerosis at 20 years. Neurology. 2007; 68: 496– 500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herbert J, Kappos L, O'Connor PW, et al. Effect of natalizumab on MS severity score in highly active patients. Poster presented at: 21st Annual Meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers; May 30–June 2, 2007; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davey BT, Donofrio MT, Moon-Grady AJ, et al. Development and validation of a fetal cardiovascular disease severity scale. Pediatr Cardiol. 2014; 35: 1174– 1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Medsger TA, Silman AJ, Steen VD, et al. A disease severity scale for systemic sclerosis: development and testing. J Rheumatol. 1999; 26: 2159– 2167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dukes CE. The classification of cancer of the rectum. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1932; 35: 323. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. Boston, MA: Little Brown & Co; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Holland R, Rechel B, Stepien K, et al. Patient's self-assessed functional status in heart failure by New York Heart Association class: a prognostic predictor of hospitalizations, quality of life, and death. J Card Fail. 2010; 16: 150– 156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Herbert J. A new classification system for multiple sclerosis. Poster presented at: 22nd Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis; September 27–30, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Poser S, Wikstrom J, Bauer HJ. Clinical data and identification of the special forms of multiple sclerosis in 1271 cases studied with a standardized documentation system. J Neurol Sci. 1979; 40: 159– 168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roxburgh RH, Seaman SR, Masterman T, et al. Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score: using disability and disease duration to rate disease severity. Neurology. 2005; 64: 1144– 1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Herbert J. Defining “malignant MS.” Poster presented at: 22nd Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis; September 27–30, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Herbert J. Rigorous definitions for “benign” and “mild” multiple sclerosis. Poster presented at: 22nd Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis; September 27–30, 2006; Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kister I, Cutter G, Salter A, Herbert J, Chamot E. Novel prediction tool that uses Patient-derived Multiple Sclerosis Severity Score (P-MSSS) successfully estimates the probability of “severe MS” at 2-year follow up. Poster presented at: 67th American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; April 18–25, 2015; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kister I, Chamot E, Bacon JH, et al. Rapid disease course in African-Americans with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010; 75: 217– 223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kister I, Chamot E, Salter AR, et al. Disability in multiple sclerosis: a reference for patients and clinicians. Neurology. 2013; 80: 1018– 1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pandey KS, Cutter G, Green R, Kister I, Herbert J. Single question patient reported disability strongly correlates with Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). Paper presented at: 31st Congress of the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis; October 8, 2015; Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Learmonth YC, Motl RW, Sandroff BM, et al. Validation of Patient Determined Disease Steps (PDDS) scale scores in persons with multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol. 2013; 13: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Antezana A, Herbert J, Chamot E, et al. Comparing disability of multiple sclerosis cohort within a tertiary clinic and volunteer North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis registry using Patient-derived Multiple Sclerosis Score. Poster presented at: 66th American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; April 26–May 3, 2014; Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Menon S, Shirani A, Zhao Y, et al. Characterising aggressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013; 84: 1192– 1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rush CA, MacLean HJ, Freedman MS. Aggressive multiple sclerosis: proposed definition and treatment algorithm. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015; 11: 379– 389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gholipour T, Healy B, Baruch NF, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of malignant multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011; 76: 1996– 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fagius J, Lundgren J, Oberg G. Early highly aggressive MS successfully treated by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Mult Scler. 2009; 15: 229– 237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Edan G, Comi G, LePage E, et al. Mitoxantrone prior to interferon beta-1b in aggressive relapsing multiple sclerosis: a 3-year randomized trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011; 82: 1344– 1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.