Abstract

Importance

Child maltreatment is a risk factor for poor health throughout the life course. Existing estimates of the proportion of the U.S. population maltreated during childhood are based on retrospective self-reports. Records of officially confirmed maltreatment have been used to produce annual rather than cumulative counts of maltreated individuals.

Objective

To estimate the proportion of U.S. children who are substantiated or indicated for maltreatment by Child Protective Services (referred to as confirmed maltreatment) by age 18.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File includes information on all U.S. children with a confirmed report of maltreatment, totaling 5,689,900 children (2004-2011). We developed synthetic cohort life tables to estimate the cumulative prevalence of confirmed childhood maltreatment by age 18.

Main Outcome Measure

The cumulative prevalence of confirmed child maltreatment between birth and age 18 by race/ethnicity, sex, and year.

Results

At 2011 rates, 12.5% [95% CI: 12.5%, 12.6%] of U.S. children will experience a confirmed case of maltreatment by age 18. Girls have a higher cumulative prevalence than boys (13.0% [95% CI: 12.9%, 13.0%] vs. 12.0% [95% CI: 12.0%, 12.1%]). Black (20.9% [95% CI: 20.8%, 21.1%]), Native American (14.5% [95% CI: 14.2%, 14.9%]), and Hispanic (13.0% [95% CI: 12.9%, 13.1%]) children have higher prevalences than White (10.7% [95% CI: 10.6%, 10.8%]) or Asian/Pacific Islander (3.8% [95% CI: 3.7%, 3.8%]) children. The risk of maltreatment is highest in the first few years of life; 2.1% [95% CI: 2,1%, 2.1%] of children have confirmed maltreatment by age 1, and 5.8% [95% CI: 5.8%, 5.9%] have confirmed maltreatment by age 5. Estimates from 2011 were consistent with those from 2004-2010.

Conclusions and Relevance

Annual rates of confirmed child maltreatment dramatically understate the cumulative number of children confirmed as maltreated during childhood. Our findings indicate that 1 in 8 U.S. children will be confirmed as victims of maltreatment by age 18, far greater than the 1 in 100 children whose maltreatment is confirmed annually. For Black children, the cumulative prevalence is 1 in 5; for Native American children, it is 1 in 7.

INTRODUCTION

Child maltreatment—encompassing both neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse of children—is associated with myriad negative physical, mental, and social outcomes. Childhood maltreatment is associated with significantly higher rates of mortality,1-3 obesity,1, 4-7 and HIV infection.1, 8 Children who experience maltreatment also have significantly more mental health problems1, 9-14 and are up to 5 times more likely to attempt suicide.1, 15 Maltreated children are also more likely to engage in crime than other children1, 16, 17 and are more than 50% more likely to have a juvenile record than other children.17 Child maltreatment also has substantial social costs. Estimates suggest that child maltreatment costs the U.S. $124 billion annually, with per-person lifetime costs higher than or comparable to those of diseases such as a stroke or type-2 diabetes.18 Childhood maltreatment has thus been referred to as “a human rights violation and a global public health problem [that] incurs huge costs for both individuals and society.”19

There is a large disparity, however, between estimates of the prevalence of maltreatment based on retrospective self-reports and those derived from officially documented maltreatment by Child Protective Services (CPS). Retrospective self-reports indicate that child maltreatment is widespread both annually and cumulatively over the course of childhood, with two studies using recent data reporting that in excess of 40% of children will be maltreated during childhood.20, 21 In contrast, official CPS data indicate that far fewer children experience maltreatment. For example, in 2011, only 0.9% of children were confirmed as victims of maltreatment.22 It is unknown to what extent the difference between these two estimates is attributable to the fact that estimates of confirmed maltreatment only capture the number of children maltreated annually and thus do not reflect the population of children maltreated over the entirety of childhood.

Although other fields have employed synthetic cohort life tables to document the cumulative risk of experiencing an event, no such attempts have been made using official child maltreatment data.23 Therefore, the purpose of this study was to use synthetic life tables to determine the percentage of U.S. children confirmed as victims of maltreatment by CPS between birth and age 18. We also estimated differences in maltreatment by race/ethnicity, sex, and year from 2004-2011.

METHODS

Data Source

To estimate the cumulative prevalence of confirmed childhood maltreatment we used data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child File from 2004-2011,24-31 and estimates of the population of U.S. children by age, race/ethnicity, sex, and year from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.32 The NCANDS Child File is composed of case-level data for each report of maltreatment that was investigated by Child Protective Services (CPS) in the United States. CPS receives reports of alleged maltreatment from individuals who are required by law to report suspected abuse or neglect (such as physicians or teachers) as well as from other sources (such as neighbors). CPS typically screens reports and then investigates those that appear most likely to involve abuse or neglect. Following the CPS investigation, a case may or may not be confirmed as maltreatment. We defined confirmed maltreatment as a report that was substantiated or indicated, meaning there was sufficient evidence for CPS to conclude that abuse or neglect had occurred. (Most states use the term “substantiated” to imply sufficient proof to confirm maltreatment occurred, but some use the term “indicated” instead.) CPS data, which are initially reported by state CPS agencies, were provided by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect at Cornell University and collected under the auspices of the Children’s Bureau, an agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services.

Population

Between 2004 and 2011, 5,689,900 children had a confirmed report of maltreatment. The vast majority (nearly 80%) of the cases in the NCANDS are cases of neglect, not abuse.

Measures

We relied on measures of age, sex, race/ethnicity, and whether it was the child’s first confirmed report of maltreatment in any given year to generate our estimates. Age, sex, and race/ethnicity were recorded by CPS caseworkers. We coded race/ethnicity into five categories: White, Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American. A child’s race/ethnicity was coded as Native American in all instances in which this group was entered. For all children who were not Native American, we coded the child as of Hispanic origin if this ethnic indicator was entered. All children who were not Native American or of Hispanic origin were considered Black if they reported Black as a remaining race and Asian/Pacific Islander if they reported as Asian/Pacific Islander and did not report as Native American, Hispanic, or Black. The remaining children were considered White. The measure of first confirmed maltreatment report was based on a variable in the original NCANDS data. In those instances in which a child had multiple CPS reports open for investigation at the same time and during the same year, only the first confirmed maltreatment report was counted. Recognizing the possibility of over counting of first confirmed maltreatments is vital for ensuring precision in the estimates because allowing individual children to have multiple first confirmed maltreatment reports in the same year would dramatically inflate estimates, an issue we return to later.

Management of Missing Data

Of all investigated reports, a total of 697,400 (12.3%) were missing information on age, sex, race/ethnicity, or prior maltreatment, with the majority of missing information involving race/ethnicity (7.0%). We addressed missing data on these four measures by generating five multiply imputed datasets. Given the low level of missing data in the NCANDS, alternative methods of dealing with missing data on these key variables produced very similar estimates.

In 20 of 408 (4.9%) state-years (with Washington, D.C. being treated as a state), the state did not report data about maltreatment to NCANDS, and information on that state is therefore missing in those years. Combined, the 4.9% of state-years missing represent 3.1% of the U.S. population between 2004 and 2011—and far less than that since 2009 (1.4% in 2009 and 1.2% in 2010 and 2011. In missing years, we assumed the state’s cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment shifted in a manner consistent with its relationship to the national estimate. So if a state’s cumulative prevalence was 1.2 times that of the national average in 2005 and missing in 2006, we assumed the state’s cumulative prevalence in 2006 was 1.2 times the national average.

Analytic Strategy

To produce cumulative estimates of children confirmed for maltreatment, we used synthetic cohort life tables,33 which were initially designed to provide estimates of life expectancy at birth and the probability of surviving to any given age from annual mortality rates. Synthetic cohort life tables can also be used to generate estimates of the proportion of individuals in a cohort who will experience an event for the first time by a given age if the age-specific risks of experiencing any event (death, marriage, maltreatment) were held at that year’s rates.33 So, for example, average life expectancy at birth in 2010 could be estimated using synthetic cohort life tables to see how long the average newborn could expect to live if they were exposed to the age-specific mortality rates in 2010 at each age. Although synthetic cohort life tables are widely used (including, for instance, to generate all Census Bureau predictions of life expectancy at birth in the U.S.), they produce the most reliable estimates when the rate of change in the age-specific rates is low and are less reliable when the rate of change in the age-specific rates is high.

In the present study, the synthetic cohort life table was structured using age-specific first-time confirmed maltreatment rates to determine the proportion of the cohort that will ever have a confirmed report of maltreatment by age 18 on the basis of first-time confirmation rates at each age between 0 and 18 for each year from 2004 to 2011. (A full life table for the analysis is presented in Table A1 for those interested in more detail.) We used Greenwood’s method34 for estimating standard errors and confidence intervals. Stata/MP 11.2 was used for all analyses.35

Table A1.

Full Synthetic Cohort Life Table for the Entire Population of US Children, 2011

| Age | nNx | nAdjusted Nx | nDx | nmx | nax | nqx | npx | nlx | ndx | 0cx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3,821,941 | 3,821,941 | 80,717 | 0.0211 | 0.5 | 0.0209 | 0.9791 | 100,000 | 2,090 | 0.0209 |

| 1 | 3,796,036 | 3,716,704 | 40,770 | 0.0110 | 0.5 | 0.0109 | 0.9891 | 97,910 | 1,068 | 0.0316 |

| 2 | 3,831,079 | 3,710,943 | 38,074 | 0.0103 | 0.5 | 0.0102 | 0.9898 | 96,864 | 989 | 0.0415 |

| 3 | 3,929,063 | 3,768,219 | 34,745 | 0.0092 | 0.5 | 0.0092 | 0.9908 | 95,906 | 880 | 0.0503 |

| 4 | 3,936,598 | 3,742,206 | 31,800 | 0.0085 | 0.5 | 0.0085 | 0.9915 | 95,062 | 804 | 0.0583 |

| 5 | 3,908,190 | 3,685,310 | 29,347 | 0.0080 | 0.5 | 0.0079 | 0.9921 | 94,297 | 747 | 0.0658 |

| 6 | 3,901,541 | 3,651,517 | 27,159 | 0.0074 | 0.5 | 0.0074 | 0.9926 | 93,592 | 692 | 0.0727 |

| 7 | 3,899,482 | 3,624,273 | 25,070 | 0.0069 | 0.5 | 0.0069 | 0.9931 | 92,942 | 639 | 0.0791 |

| 8 | 3,873,841 | 3,577,368 | 22,742 | 0.0064 | 0.5 | 0.0063 | 0.9937 | 92,347 | 584 | 0.0849 |

| 9 | 3,886,529 | 3,568,077 | 21,207 | 0.0059 | 0.5 | 0.0059 | 0.9941 | 91,806 | 542 | 0.0903 |

| 10 | 3,972,977 | 3,627,594 | 20,178 | 0.0056 | 0.5 | 0.0055 | 0.9945 | 91,307 | 505 | 0.0954 |

| 11 | 4,000,256 | 3,633,997 | 18,970 | 0.0052 | 0.5 | 0.0052 | 0.9948 | 90,844 | 471 | 0.1001 |

| 12 | 3,947,683 | 3,569,272 | 18,816 | 0.0053 | 0.5 | 0.0053 | 0.9947 | 90,414 | 473 | 0.1048 |

| 13 | 3,948,136 | 3,552,707 | 18,878 | 0.0053 | 0.5 | 0.0053 | 0.9947 | 89,984 | 474 | 0.1096 |

| 14 | 3,960,340 | 3,546,689 | 18,743 | 0.0053 | 0.5 | 0.0053 | 0.9947 | 89,555 | 469 | 0.1143 |

| 15 | 4,002,101 | 3,567,166 | 18,554 | 0.0052 | 0.5 | 0.0052 | 0.9948 | 89,132 | 460 | 0.1189 |

| 16 | 4,083,721 | 3,623,080 | 16,082 | 0.0044 | 0.5 | 0.0044 | 0.9956 | 88,720 | 390 | 0.1228 |

| 17 | 4,160,067 | 3,676,308 | 10,349 | 0.0028 | 0.5 | 0.0028 | 0.9972 | 88,371 | 247 | 0.1252 |

Note: Where nNx is the population of children in the population in the interval, nAdjusted Nx is the number of children in the population at risk of experiencing the event in the interval, nDx is the number of children in the population who experience the event in the interval, nmx is the rate at which children experience the event in the interval, nax is how far into the interval the average child who experiences the event does so, nqx is the probability of experiencing the event in the interval (contingent upon making it to the beginning of this interval without experiencing the event), npx is the probability of not experiencing the event in the interval (contingent upon making it to the beginning of this interval without experiencing the event), nlx is the number of children in a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 children who will not have experienced the event by the beginning of the interval, ndx is the number of children in a hypothetical cohort of 100,000 children who will experience the event during the interval, and 0cx is the cumulative probability of ever experiencing that event by the end of the interval.

Human Subjects Protections

All analyses were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University.

RESULTS

A total of 670,000 children (0.9% of all U.S. children) experienced a confirmed report of maltreatment in 2011 (Table 1). The percentage of White children in the U.S. with a confirmed report of maltreatment (0.8%) was significantly lower than the percentage of Black (1.5%), Native American (1.1%), and Hispanic (0.9%) children, although higher than the percentage of Asian/Pacific Islanders (0.2%). Rates of confirmed maltreatment were slightly but significantly higher for males than females. Rates of confirmed maltreatment were significantly higher in the North (1.0%), the South (1.0%), and the Midwest (0.9%) than in the West (0.8%).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, 2011

| All US Children | All CPS-Confirmed Maltreated Children |

First-Time CPS-Confirmed Maltreated Children |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Age (Mean) | 9.1 | 6.8 | 6.2 | |||

|

| ||||||

| N | N | % | N | % | ||

| All Children | Total | 75,091,700 | 670,000 | 0.9 | 492,400 | 0.7 |

| White | 41,327,000 | 317,900 | 0.8 | 227,200 | 0.5 | |

| Black | 11,602,400 | 174,400 | 1.5 | 127,700 | 1.1 | |

| Hispanic Origin | 16,921,800 | 153,400 | 0.9 | 119,000 | 0.7 | |

| Asian/PI | 3,863,000 | 9,300 | 0.2 | 7,800 | 0.2 | |

| Native American | 1,377,500 | 15,000 | 1.1 | 10,800 | 0.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| Male | Total | 38,029,200 | 326,800 | 0.9 | 239,700 | 0.6 |

| White | 20,865,000 | 155,500 | 0.7 | 110,800 | 0.5 | |

| Black | 5,950,600 | 86,400 | 1.5 | 63,400 | 1.1 | |

| Hispanic Origin | 8,592,000 | 73,100 | 0.9 | 56,600 | 0.7 | |

| Asian | 1,938,500 | 4,600 | 0.2 | 3,800 | 0.2 | |

| Native American | 683,100 | 7,300 | 1.1 | 5,200 | 0.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| Female | Total | 37,062,400 | 343,200 | 0.9 | 252,700 | 0.7 |

| White | 20,462,000 | 162,400 | 0.8 | 116,400 | 0.6 | |

| Black | 5,651,800 | 88,000 | 1.6 | 64,300 | 1.1 | |

| Hispanic Origin | 8,329,800 | 80,200 | 1.0 | 62,500 | 0.7 | |

| Asian | 1,924,500 | 4,800 | 0.2 | 4,000 | 0.2 | |

| Native American | 694,300 | 7,800 | 1.1 | 5,600 | 0.8 | |

|

| ||||||

| Location | Northeast | 12,915,900 | 122,700 | 1.0 | 77,600 | 0.6 |

| Midwest | 16,060,400 | 143,100 | 0.9 | 106,700 | 0.7 | |

| West | 18,002,200 | 135,700 | 0.8 | 109,400 | 0.6 | |

| South | 28,113,190 | 268,500 | 1.0 | 198,700 | 0.7 | |

Note: All values have been rounded to the hundreds to highlight that they are estimates, not exact counts.

Of the 670,000 children confirmed as victims of maltreatment in 2011, it was the first confirmed report for 73.4% (492,400) (Table 1). Those children for whom it was a first-time confirmed report were significantly more likely to be Black, Native American, or Hispanic than White or Asian/Pacific Islander. They were also significantly more likely to be female, although sex differences in this population were small (0.7% to 0.6%).

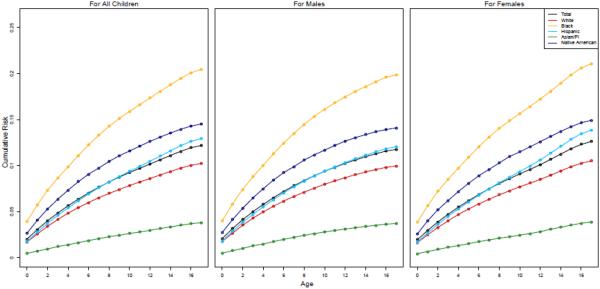

For all U.S. children, the cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment was 12.5% [95% CI: 12.5%, 12.6%] in 2011 (Figure 1; Table 2). That is, approximately 1 in 8 American children were confirmed for maltreatment between birth and age 18. This is 13.9 times as many children as experience a confirmed maltreatment case annually (12.5/0.9; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of Children Having Ever Experienced Confirmed Maltreatment, 2011

Table 2.

Cumulative Rates of Confirmed CPS Maltreatment by Race/Ethnicity and Age, 2011

| Age | Total (95% CI) | White (95% CI) | Black (95% CI) | Hispanic (95% CI) | Asian/PI (95% CI) | Native American (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 0 | 0.021 (0.021, 0.021) | 0.018 (0.018, 0.018) | 0.040 (0.040, 0.041) | 0.018 (0.017, 0.018) | 0.005 (0.004, 0.005) | 0.026 (0.025, 0.028) |

| 1 | 0.032 (0.031, 0.032) | 0.027 (0.027, 0.027) | 0.059 (0.058, 0.060) | 0.028 (0.028, 0.029) | 0.007 (0.007, 0.008) | 0.040 (0.039, 0.042) |

| 2 | 0.041 (0.041, 0.042) | 0.036 (0.036, 0.036) | 0.075 (0.074, 0.076) | 0.038 (0.037, 0.038) | 0.010 (0.009, 0.010) | 0.053 (0.051, 0.055) |

| 3 | 0.050 (0.050, 0.051) | 0.044 (0.043, 0.044) | 0.089 (0.088, 0.090) | 0.046 (0.046, 0.047) | 0.012 (0.011, 0.013) | 0.063 (0.061, 0.066) |

| 4 | 0.058 (0.058, 0.059) | 0.051 (0.051, 0.051) | 0.102 (0.101, 0.103) | 0.055 (0.054, 0.055) | 0.014 (0.013, 0.015) | 0.073 (0.071, 0.076) |

| 5 | 0.066 (0.065, 0.066) | 0.057 (0.057, 0.058) | 0.114 (0.113, 0.115) | 0.062 (0.062, 0.063) | 0.016 (0.016, 0.017) | 0.083 (0.080, 0.085) |

| 6 | 0.073 (0.072, 0.073) | 0.063 (0.063, 0.064) | 0.126 (0.125, 0.127) | 0.070 (0.069, 0.070) | 0.019 (0.018, 0.019) | 0.091 (0.088, 0.093) |

| 7 | 0.079 (0.079, 0.079) | 0.068 (0.068, 0.069) | 0.137 (0.136, 0.138) | 0.077 (0.076, 0.077) | 0.021 (0.020, 0.022) | 0.098 (0.095, 0.100) |

| 8 | 0.085 (0.085, 0.085) | 0.073 (0.073, 0.074) | 0.147 (0.146, 0.148) | 0.083 (0.082, 0.084) | 0.023 (0.022, 0.024) | 0.105 (0.102, 0.108) |

| 9 | 0.090 (0.090, 0.091) | 0.078 (0.077, 0.078) | 0.156 (0.154, 0.157) | 0.089 (0.088, 0.090) | 0.024 (0.024, 0.025) | 0.111 (0.108, 0.114) |

| 10 | 0.095 (0.095, 0.096) | 0.082 (0.082, 0.083) | 0.163 (0.162, 0.165) | 0.095 (0.094, 0.095) | 0.026 (0.025, 0.027) | 0.116 (0.113, 0.119) |

| 11 | 0.100 (0.100, 0.100) | 0.086 (0.086, 0.087) | 0.171 (0.170, 0.172) | 0.100 (0.099, 0.101) | 0.028 (0.027, 0.029) | 0.121 (0.118, 0.124) |

| 12 | 0.105 (0.104, 0.105) | 0.090 (0.090, 0.091) | 0.178 (0.177, 0.179) | 0.105 (0.105, 0.106) | 0.030 (0.029, 0.031) | 0.126 (0.123, 0.130) |

| 13 | 0.110 (0.109, 0.110) | 0.094 (0.094, 0.095) | 0.185 (0.184, 0.187) | 0.111 (0.110, 0.112) | 0.032 (0.031, 0.033) | 0.131 (0.128, 0.134) |

| 14 | 0.114 (0.114, 0.115) | 0.098 (0.097, 0.099) | 0.193 (0.191, 0.194) | 0.117 (0.116, 0.118) | 0.034 (0.033, 0.035) | 0.136 (0.132, 0.139) |

| 15 | 0.119 (0.118, 0.119) | 0.102 (0.101, 0.102) | 0.200 (0.198, 0.201) | 0.122 (0.121, 0.123) | 0.035 (0.034, 0.036) | 0.140 (0.136, 0.143) |

| 16 | 0.123 (0.122, 0.123) | 0.105 (0.104, 0.106) | 0.206 (0.204, 0.207) | 0.127 (0.126, 0.128) | 0.037 (0.036, 0.038) | 0.143 (0.140, 0.146) |

| 17 | 0.125 (0.125, 0.126) | 0.107 (0.106, 0.108) | 0.209 (0.208, 0.211) | 0.130 (0.129, 0.131) | 0.038 (0.037, 0.039) | 0.145 (0.142, 0.149) |

The cumulative risks of confirmed maltreatment differed by race/ethnicity (Figure 1; Table 2). Black children had the highest risks at 20.9% [95% CI: 20.8%, 21.1%], followed by Native American children at 14.5% [95% CI: 14.2%, 14.9%], Hispanic children at 13.0% [95% CI: 12.9%, 13.1%], White children at 10.7% [95% CI: 10.6%, 10.8%], and Asian/Pacific Islander children at 3.8% [95% CI: 3.7%, 3.9%]. All differences were statistically significant.

Sex differences in the cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment were small but statistically significant (Figure 1). The cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment was 13.0% [95% CI: 12.9%, 13.0%] for girls vs 12.1% [95% CI: 12.0%, 12.1%] for boys. These small but significant differences held for all racial/ethnic groups. Black females had the highest cumulative prevalence at 21.6% [95% CI: 21.5%, 21.8%].

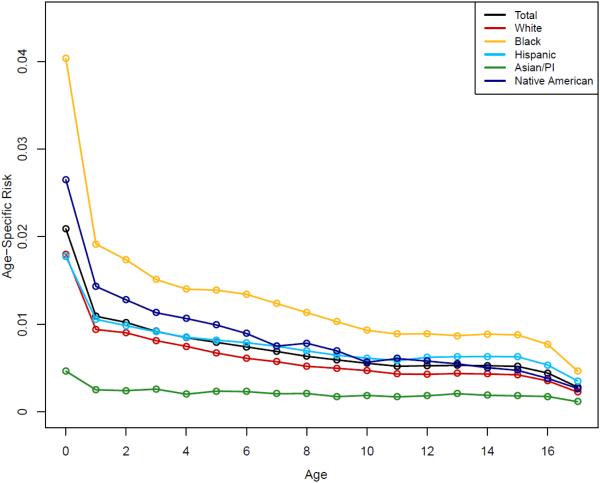

First-time rates of confirmed maltreatment were especially high during the first few years of life (Figure 2). The rate of first confirmed maltreatment was highest in the first year of life, during which 2.1% [95% CI: 2.1%, 2.1%] of children had a confirmed report of maltreatment. This figure was roughly halved to 1.1% [95% CI: 1.1%, 1.1%] during the second year of life. The rate then gradually decreased until age 11, where it essentially held steady through age 18.

Figure 2.

Age–Specific Risk for First Confirmed Maltreatment, 2011

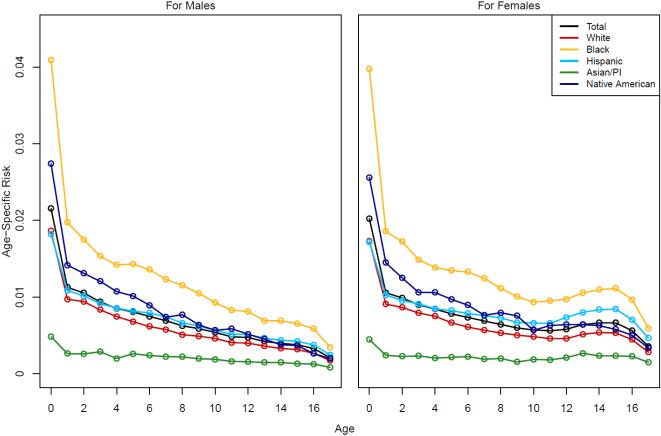

All racial/ethnic groups and both sexes experienced similar age-patterns of first reports of confirmed maltreatment (Figure 2; Figure A1). Black children had the highest occurrence of first-time confirmed maltreatment before their first birthday, with 4.0% [95% CI: 4.0%, 4.1%] of Black children experiencing this outcome.

Figure A1.

Age–Specific Risk for First Confirmed Maltreatment, 2011

For the total population, roughly one-quarter of children’s first confirmed reports occurred before age 2, with 3.2% [95% CI: 3.2%, 3.2%] of all children confirmed as a victim of child maltreatment before their second birthday (Table 2). Nearly half of confirmed maltreatment happened before age 5, with 5.8% [95% CI: 5.8%, 5.9%] of all children confirmed victims of child maltreatment before their fifth birthday (Table 2).

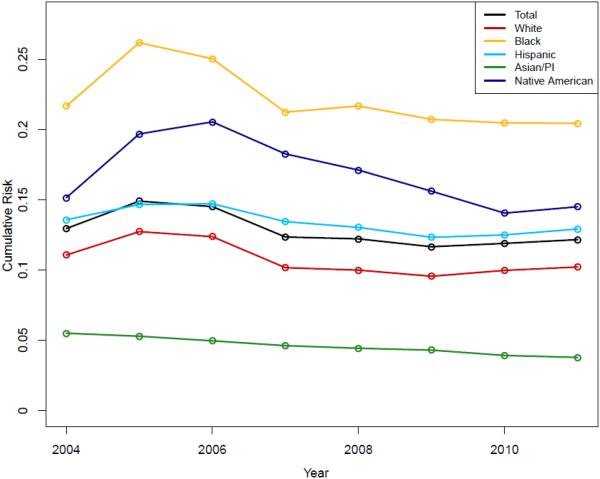

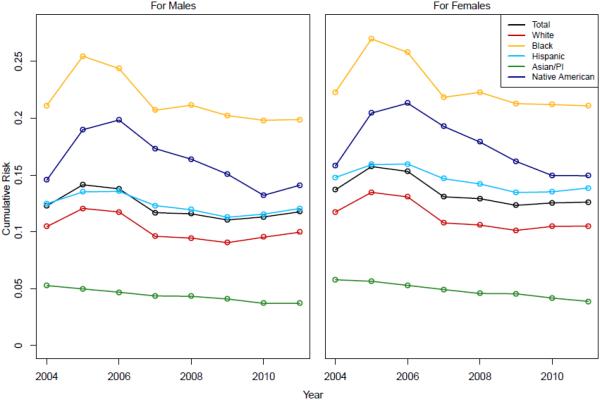

When data were examined from the eight years included in our analyses, the cumulative prevalence differed significantly between 2004 and 2011 for all U.S. children, but even in the year with the lowest prevalence, it was high. The cumulative prevalence fluctuated from 12.0% [95% CI: 12.0%, 12.0%] in 2009 to 15.1% [95% CI: 15.1%, 15.1%] in 2005 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cumulative Risk of Confirmed Maltreatment by Age 18, 2004–2011

Patterns were similar across race/ethnicity (Figure 3; Figure A2). The largest fluctuations were for Blacks, for whom it fluctuated from 20.9% [95% CI: 20.9%, 21.0%] in 2011 to 26.2% in 2005 [95% CI: 26.1%, 26.3%], and Native Americans, for whom it fluctuated from 14.0% [95% CI: 13.7%, 14.2%] in 2010 to 20.5% [95% CI: 20.2%, 20.8%] in 2006.

Figure A2.

Cumulative Risk of Confirmed Maltreatment by Age 18, 2004–2011

DISCUSSION

At 2011 rates, between birth and their 18th birthday, 1 in 8 U.S. children will experience maltreatment so persistent or so severe that it results in a state-confirmed maltreatment report. For Black and Native American children, the cumulative prevalence is even greater. About 1 in 5 Black children and 1 in 7 Native American children will have a confirmed maltreatment report before age 18. This means Black children are about as likely to have a confirmed report of maltreatment during childhood as they are to complete college.36

The estimates generated in this analysis are significant for at least two reasons. First, this study provides the first national estimate of the proportion of children who experience maltreatment that is reported to and confirmed by CPS. Although other data sources have been used to produce state-37, 38 or county-specific39 estimates, this is the first study to present national estimates of the cumulative prevalence of child maltreatment.

Second, these data highlight that the burden of confirmed maltreatment is far greater than suggested by single-year national estimates of confirmed child maltreatment and that the risk of maltreatment is particularly high for Black children, who had cumulative risks of confirmed maltreatment in excess of 25% for many years (and never lower than 20%). As such, these estimates are valuable for informing public health monitoring and investments.

This study, nonetheless, has several limitations.

First, the estimates presented here may underestimate the true cumulative prevalence of maltreatment and misestimate racial/ethnic disparities in child maltreatment because our estimates are based on maltreatment that came to the attention of CPS and was confirmed by CPS. Indeed, the most recent estimate of the cumulative risk of self-reported maltreatment in a national sample shows that over 40% of children ever experience maltreatment, indicating that the cumulative prevalence of self-reported maltreatment is roughly three times the cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment.20 Although this is a limitation of all CPS data, it still bears mentioning.40

Second, although the level of missing data in NCANDS is modest, especially since 2004, our estimates may be slightly imprecise because children missing information on multiple measures included in our analysis potentially introduce bias.

Third, because CPS data are collected by states and then aggregated, children may be counted more than once if maltreated in multiple states in different years. Although this is a limitation because it makes our estimates less precise, its effect on our estimates is likely small.

Fourth, definitions of maltreatment (a) vary across states and (b) have also been changing over time within states. Variation in definitions across states means that the national estimates we have produced are based not on a single definition of maltreatment, as would be ideal, but on many definitions of maltreatment. Definitional variation over time also means that we are uncertain as to how much of the change in the cumulative risk of confirmed maltreatment is due to actual changes in rates of maltreatment versus changes in definitions of maltreatment. We thus cannot speak with confidence about how the cumulative risk of actual maltreatment has changed over this period.

Fifth, if the NCANDS data incorrectly code later confirmed reports of maltreatment as first confirmed reports, we would overestimate the cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment. In order to address this possibility, we followed a cohort of children from birth in 2004 until 2011. Results suggested that few later confirmed maltreatment cases were incorrectly coded as first confirmed maltreatment cases. This finding is relevant because it means that the data are reliable to age 8. In light of this, even if we assume that all first confirmed maltreatments after age 8 are incorrectly coded as first maltreatments (which is unlikely), the lowest the cumulative risk of confirmed maltreatment could be is 8.5% (the cumulative risk by age 8), which is two-thirds of the cumulative risk by age 18 (12.5%). For Black children, the lowest the cumulative risk of confirmed maltreatment could be is 14.7% (relative to 20.9% by age 18).

Sixth, because of the structure of the NCANDS data, we were not able to estimate differences in the cumulative prevalence of different types of maltreatment (such as neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse), as is common in much research in this area, 20,21 because doing so would have involved using a multiple decrement life table for a birth cohort and made it possible for us to consider cumulative prevalences only to age eight rather than age eighteen.

Finally, because the rate of first-time confirmed maltreatment has decreased sharply in some recent years (although less than the total confirmed maltreatment rate), our synthetic cohort life table estimates will be higher the cumulative prevalence of confirmed maltreatment in 2012, assuming rates of first-time confirmed maltreatment decline. However, since first-time rates of confirmed maltreatment have declined only moderately since 2007, as indicated by the stable cumulative prevalence for the total population from 2007 to 2011 (Figure 3; Figure A2), we expect the estimates presented here to be quite similar to what the 2012 and 2013 data find.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from these analyses—which provide cumulative rather than annual estimates—indicate that confirmed child maltreatment is common, on the scale of other major public health concerns that affect child health and wellbeing. Moreover, child maltreatment is unequally distributed by race/ethnicity, with many more Black, Native American, and Hispanic children experiencing a confirmed report of maltreatment at some point than White or, especially, Asian/Pacific Islander children. Because child maltreatment is also a risk factor for poor mental and physical health outcomes throughout the life-course, the results of this study provide valuable epidemiological information. Being able to accurately assess the extent and severity of maltreatment across populations and time can inform policies and practices that can be used to not only reduce maltreatment but also improve population health and reduce health disparities.

Acknowledgments

The collector of the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) Child Files, 2004-2011, the funder, NDACAN, Cornell University, and the agents or employees of these institutions bear no responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. The information and opinions expressed reflect solely the opinions of the authors. The authors thank Michael Dineen for data assistance and Debra Houle for computing support. Natalia Emanuel had full access to all of the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest or funding to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Putnam-Hornstein E. Report of maltreatment as a risk factor for injury death: A prospective birth cohort study. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16(3):163–174. doi: 10.1177/1077559511411179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Putnam-Hornstein E, Cleves MA, Licht R, Needell B. Risk of fatal injury in young children following abuse allegations: Evidence from a prospective, population-based study [published ahead of print on August 15, 2013] American Journal of Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301516. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Childhood adversities associated with risk for eating disorders or weight problems during adolescence or early adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(3):394–400. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noll JG, Zeller MH, Trickett PK, Putnam FW. Obesity risk for female victims of childhood sexual abuse: a prospective study. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1):e61–e67. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas C, Hyppönen E, Power C. Obesity and type 2 diabetes risk in midadult life: the role of childhood adversity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1240–e1249. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lissau I, Sorensen TI. Parental neglect during childhood and increased risk of obesity in young adulthood. Lancet. 1994;343(8893):324–327. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson HW, Widom CS. An examination of risky sexual behavior and HIV in victims of child abuse and neglect: a 30-year follow-up. Health Psychology. 2008;27(2):149–158. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. The long-term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: An exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):697–715. doi: 10.1023/A:1013085904337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(6):607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl RC, Rupert LJ, Egolf BP, Lutz JG. Risk factors for behavioral dysfunction: the relative impact of maltreatment, SES, physical health problems, cognitive ability, and quality of parent-child interaction. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(2):191–203. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)00116-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molnar BE, Buka SL, Kessler RC. Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(5):753–760. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.5.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13(04):957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Currie J, Tekin E. Understanding the Cycle Childhood Maltreatment and Future Crime. Journal of Human Resources. 2012;47(2):509–549. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244(4901):160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36(2):156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reading R, Bissell S, Goldhagen J, Harwin J, Masson J, Moynihan S, et al. Promotion of children's rights and prevention of child maltreatment. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):332–343. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61709-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Violence, Crime, and Abuse Exposure in a National Sample of Children and Youth: An Update. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167(7):614–621. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Administration for Children and Families. Administration on Children, Youth, and Families. Children’s Bureau Child Maltreatment 2011. Available at: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm11.pdf.

- 23.Wildeman C. Parental imprisonment, the prison boom, and the concentration of childhood disadvantage. Demography. 2009;46(2):265–280. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2004. 2006.

- 25.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2005. 2007.

- 26.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2006. 2008.

- 27.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2007. 2009.

- 28.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2008. 2010.

- 29.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2009. 2011.

- 30.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2010. 2012.

- 31.National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (Child File), FFY 2011. 2013.

- 32.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC WONDER Online Database Bridged-Race Population Estimates 1990-2009 Request. http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2009.html.

- 33.Preston SH, Heuveline P, Guillot M. Demography: Measuring and Modeling Population Processes. Blackwell Publishers; Oxford: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Greenwood M. A Report on the Natural Duration of Cancer. Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects. Ministry of Health. 1926;(33) [Google Scholar]

- 35.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pettit B, Western B. Mass imprisonment and the life course: Race and class inequality in US incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(2):151–169. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Putnam-Hornstein E, Needell B, King B, Johnson-Motoyama M. Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2013;37(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magruder J, Shaw TV. Children ever in care: An examination of cumulative disproportionality. Child Welfare. 2008;87(2):169–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabol W, Coulton C, Polousky E. Measuring child maltreatment risk in communities: A life table approach. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28(9):967–983. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drake B, Jolley JM, Lanier P, Fluke J, Barth RP, Jonson-Reid M. Racial bias in child protection? A comparison of competing explanations using national data. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):471–478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]