ABSTRACT

Store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) occurs when loss of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stimulates the Ca2+ sensor, STIM, to cluster and activate the plasma membrane Ca2+ channel Orai (encoded by Olf186-F in flies). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs, which are encoded by a single gene in flies) are assumed to regulate SOCE solely by mediating ER Ca2+ release. We show that in Drosophila neurons, mutant IP3R attenuates SOCE evoked by depleting Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin. In normal neurons, store depletion caused STIM and the IP3R to accumulate near the plasma membrane, association of STIM with Orai, clustering of STIM and Orai at ER–plasma-membrane junctions and activation of SOCE. These responses were attenuated in neurons with mutant IP3Rs and were rescued by overexpression of STIM with Orai. We conclude that, after depletion of Ca2+ stores in Drosophila, translocation of the IP3R to ER–plasma-membrane junctions facilitates the coupling of STIM to Orai that leads to activation of SOCE.

KEY WORDS: Ca2+ signalling, Drosophila, IP3 receptor, Orai, STIM, Store-operated Ca2+ entry

Summary: In Drosophila neurons, mutant IP3 receptors disrupt store-operated Ca2+ entry by destabilizing interaction of STIM with the Ca2+ channel, Orai. The interactions could coordinate store emptying with Ca2+ entry.

INTRODUCTION

Receptors that stimulate phospholipase C and, hence, formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) typically evoke both release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) through IP3 receptors (IP3Rs) and Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane. The latter is usually mediated by store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE), an almost ubiquitously present pathway through which empty Ca2+ stores stimulate Ca2+ entry across the plasma membrane (Putney and Tomita, 2012). The core molecular components of SOCE are stromal interaction molecule (STIM) and Orai (the gene for which is also known as Olf186-F in flies) (Hogan, 2015; Lewis, 2012). Orai forms a hexameric Ca2+-selective ion channel in the plasma membrane (Hou et al., 2012) and STIM is the Ca2+ sensor anchored in ER membranes (Carrasco and Meyer, 2011). Ca2+ dissociates from the luminal EF-hand of STIM when Ca2+ is lost from the ER. This causes STIM to oligomerize, unmasking residues that interact with Orai, and allowing STIM to accumulate at ER–plasma-membrane junctions, where the gap between membranes is narrow enough to allow the cytosolic CAD region of STIM to bind directly to Orai (Hogan, 2015). That interaction traps STIM and Orai clusters within ER–plasma-membrane junctions and it stimulates opening of the Orai channel (Wu et al., 2014). Additional proteins also regulate SOCE, often by modulating interactions between STIM and Orai (Srikanth and Gwack, 2012) or by facilitating their interactions by stabilizing ER–plasma-membrane junctions (Cao et al., 2015) or the organization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)-enriched membrane domains (Sharma et al., 2013).

SOCE can be activated by thapsigargin, which depletes Ca2+ stores by inhibiting the ER Ca2+ pump, but for SOCE evoked by physiological stimuli, the Ca2+ stores are depleted by activation of IP3Rs. In the present study, we use genetic manipulations in Drosophila neurons to ask whether IP3Rs regulate SOCE solely by mediating Ca2+ release from the ER or whether they can also play additional roles downstream of store depletion. Drosophila is well suited to this analysis because single genes encode IP3R, STIM and Orai, whereas vertebrates have several genes for each of these proteins. Our results demonstrate that in Drosophila, its IP3R contributes to assembly of the STIM–Orai complex. Comparison of results from Drosophila and vertebrates suggests that the STIM–Orai complex might assemble in plasma-membrane–ER regions equipped to allow local depletion of Ca2+ stores.

RESULTS

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate SOCE in Drosophila

SOCE evoked by depleting ER Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin in Drosophila neurons was abolished by RNA interference (RNAi) treatment for STIM or Orai (see Fig. 1D; Venkiteswaran and Hasan, 2009). This is consistent with evidence that STIM and Orai are core components of SOCE. Subsequent experiments examine the role of the IP3R, which is encoded by a single gene (itpr) in Drosophila, in regulating SOCE. To characterize SOCE in Drosophila neurons with mutant itpr, we examined five hetero-allelic combinations of a 15-residue C-terminal deletion and three point mutations located in different parts of the IP3R (Banerjee et al., 2004; Joshi et al., 2004) (Fig. 1A). We used these combinations because the adults with these mutations are viable with distinct flight phenotypes, whereas homozygotes and other hetero-allelic combinations are lethal (Joshi et al., 2004). We also used neurons heterozygous for each individual mutation. The peak Ca2+ signals evoked by addition of thapsigargin in Ca2+-free medium and the response to restoration of extracellular Ca2+ (SOCE) were measured in primary neuronal cultures for each genotype (Fig. 1B–D). Our use of fluo 4 fluorescence changes (ΔF/F0, see Materials and Methods) to report cytosolic free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]c) is vindicated by evidence that [Ca2+]c in unstimulated cells was unaffected by mutant IP3R (Fig. S1A) and the peak fluorescence changes evoked by SOCE in wild-type neurons were only 32±14% (mean±s.d., n=9) of those evoked by saturating the indicator with Ca2+.

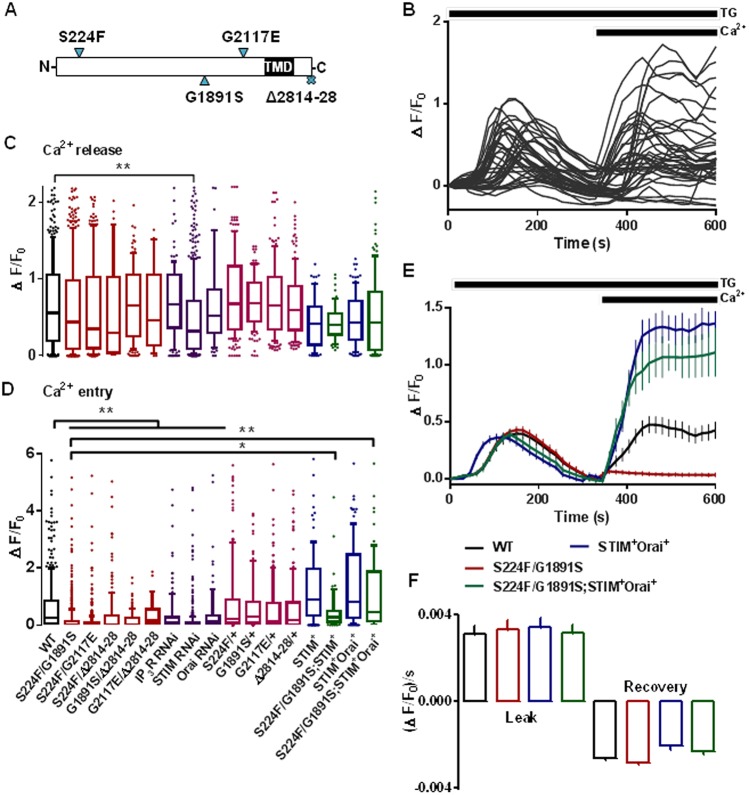

Fig. 1.

SOCE in Drosophila neurons is attenuated by mutant IP3Rs and rescued by overexpression of STIM and Orai. (A) IP3R mutations examined. TMD, transmembrane domains. (B) Traces from 40 individual wild-type (WT) neurons showing Ca2+ release evoked by thapsigargin (TG, 10 µM) in Ca2+-free HBM, and SOCE after restoration of extracellular Ca2+ (2 mM). (C,D) Summary results for peak responses evoked by thapsigargin (Ca2+ release) and Ca2+ restoration (SOCE) for neurons with the indicated genotypes and for WT neurons treated with the indicated siRNA. The box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the 10–90th percentiles. Outliers are represented by dots. Results are from >100 cells from at least five independent experiments.*P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Wilcoxon signed-rank post-hoc test). (E) Responses of neurons from WT or itpr mutants (S224F/G1891S) alone and after overexpression of STIM and Orai. Results (mean±s.d., from >100 cells from at least five independent experiments) show Ca2+ release evoked by thapsigargin (10 µM) in Ca2+-free HBM, and SOCE evoked by subsequent addition of extracellular Ca2+ (2 mM). (F) Rates of Ca2+ leak and recovery from the thapsigargin-evoked Ca2+ release, calculated from E. The colour key applies to panels E and F. STIM+, overexpression of STIM; Orai+, overexpression of Orai.

SOCE was significantly reduced in all five itpr mutant combinations (Fig. 1D; Table S1). However, the resting [Ca2+]c and thapsigargin-evoked release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores were unaffected, confirming that mutant IP3R selectively perturbed SOCE (Fig. 1C; Fig. S1A). The reduced SOCE in itpr mutant neurons was not, therefore, restricted to a single combination of mutant alleles. Mutant combinations in the ligand-binding domain (S224F), modulatory domain (G1891S and G2117E) and C-terminus (Δ2814–2828) of the IP3R all inhibited SOCE. SOCE was not significantly affected in neurons heterozygous for the individual mutants (Fig. 1D; Table S1). In adult flies, these heterozygous itpr mutants also have no significant effect on viability or flight phenotype (Banerjee et al., 2004; Joshi et al., 2004). The results establish that attenuated SOCE in Drosophila neurons is due to a perturbation of IP3R function in the recessive heteroallelic mutant combinations. This conclusion is supported by evidence that RNAi-mediated knockdown of IP3R also inhibited thapsigargin-evoked SOCE (Fig. 1D). It might seem surprising that so many combinations of four different itpr mutants should inhibit SOCE. However, selection of the original mutant combinations was based on flight phenotypes (Banerjee et al., 2004), and restoring SOCE can rescue these flight defects (Agrawal et al., 2010). The original selection might therefore have preferentially identified itpr mutants that attenuate SOCE. Immunoblots established that expression of IP3R, STIM and Orai were similar in the larval central nervous system from wild-type and itpr mutant flies (Fig. S1B,C).

Similar functional consequences of mutant itpr were observed in cultured haemocytes from Drosophila larvae, where itpr mutants attenuated thapsigargin-evoked SOCE without affecting basal [Ca2+]c or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (Fig. S2).

The results so far establish that loss of IP3R or mutations within IP3R attenuate SOCE without affecting the Ca2+ content of the intracellular stores. The effects are not due to loss of STIM or Orai.

Over-expressed STIM and Orai restores SOCE in neurons with mutant IP3Rs

We used the mutant itpr combination itprS224F/G1891S to examine the effects of overexpressing STIM and Orai on SOCE in cultured neurons. We chose this combination because it has been the most extensively studied of the heteroallelic mutant itpr combinations (Agrawal et al., 2010; Venkiteswaran and Hasan, 2009). The response to thapsigargin in Ca2+-free medium was unaffected by overexpression of STIM and Orai (Fig. 1C,E). Rates of recovery from these [Ca2+]c increases were also unaffected (Fig. 1F). These results demonstrate that the ER Ca2+ content, passive leak of Ca2+ from the ER, and rates of Ca2+ extrusion from the cytosol were similar in neurons with mutant or wild-type IP3R, and unaffected by overexpression of STIM and Orai. However, SOCE in neurons expressing mutant IP3R was restored by overexpression of STIM with Orai (Fig. 1D,E). This is consistent with behavioural analyses (Fig. S3A,B) (Agrawal et al., 2010). A similar restoration of SOCE upon overexpression of STIM has been reported in neurons in which IP3R expression was reduced by small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Deb et al., 2016). Hence, even though mutant IP3Rs do not affect expression of STIM or Orai, the attenuated SOCE can be compensated for by overexpressing STIM and Orai (Fig. 1D). The results so far suggest that the IP3R regulates SOCE downstream of ER Ca2+ release, perhaps by influencing interactions between STIM and Orai.

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate the association of STIM with Orai after store depletion

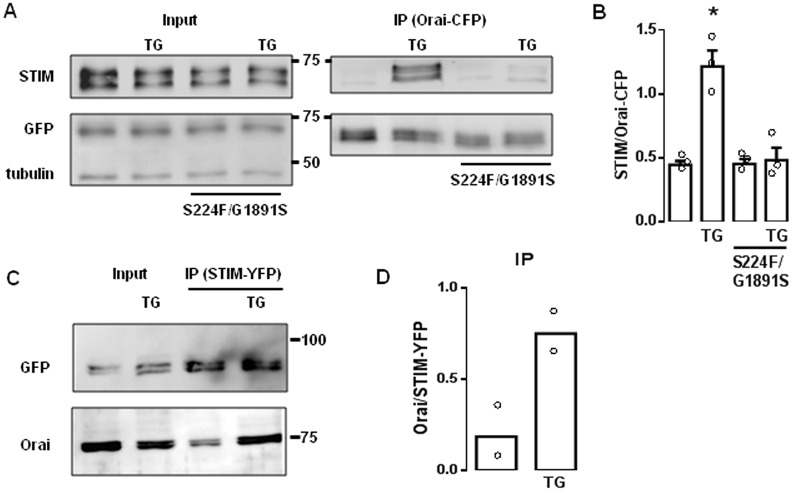

We tested whether IP3R mutations affect interactions between STIM and Orai using an ectopically expressed dOrai-CFP+ transgene with a pan-neuronal driver (ElavC155). This allowed immunoprecipitation of Orai with an anti-GFP antibody. Expression of Orai–CFP did not restore SOCE in itpr mutant neurons (Fig. S3C,D). Treatment with thapsigargin enhanced the pulldown of STIM with anti-GFP antibody from lysates of wild-type brain, consistent with enhanced interaction between STIM and Orai after store depletion. However, the pulldown of STIM from thapsigargin-treated brains with mutant IP3R was much reduced (Fig. 2A,B). In the reciprocal immunoprecipitation using wild-type brain expressing STIM–YFP, thapsigargin increased the pulldown of Orai with the anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 2C,D). There was no detectable IP3R in this immunoprecipitate (data not shown), suggesting that any interaction between IP3R and STIM or Orai, whether direct or through other proteins, might be too weak to survive immunoprecipitation. It was impracticable to assess the effects of mutant IP3R in these immunoprecipitation experiments because STIM–YFP rescued the mutant IP3R phenotypes (Fig. 1D) (Agrawal et al., 2010). These results suggest that wild-type IP3R stabilizes interactions between STIM and Orai after depletion of Ca2+ stores.

Fig. 2.

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate association of STIM and Orai after store depletion. (A) Western blots from brains of larval Drosophila expressing Orai–CFP with WT or mutant IP3Rs, and treated with thapsigargin (TG, 10 µM in Ca2+-free HBM for 10 min) as indicated. The input lysates (equivalent to 20% of the immunoprecipitated sample) and anti-GFP immunoprecipitates (IP) are shown. α-tubulin provides a loading control. The positions of molecular mass markers (kDa) are shown between blots. (B) Summary results for the ratio of the intensities of the STIM to Orai–CFP bands (mean±s.e.m., n=3). *P<0.05, paired Student's t-test relative to the respective control. (C) WT brains expressing STIM–YFP show results of immunoprecipitation (with anti-GFP antibody) after treatment with thapsigargin as indicated. The lysate lanes contain the equivalent of 20% of the immunoprecipitated sample lanes. (D) Summary results show the ratio of the intensities of the Orai to STIM–YFP bands (mean and individual values are shown; n=2).

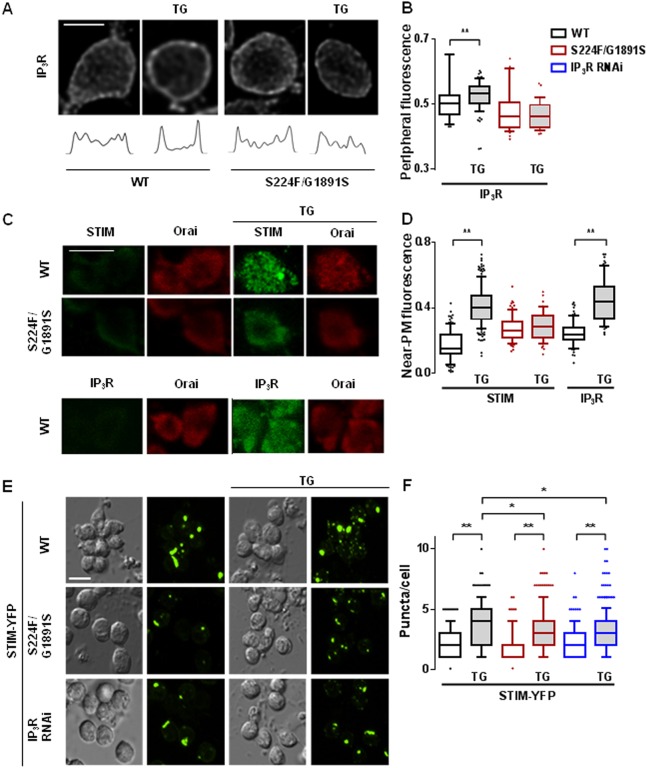

To avoid reversal of attenuated SOCE in neurons with mutant IP3Rs after overexpression of STIM (Fig. 1D), we used immunostaining of fixed neurons to examine the effects of store depletion on the distribution of endogenous STIM, Orai and IP3R. We quantified the near-plasma-membrane distribution of STIM and IP3R by measuring either peripheral fluorescence in confocal sections across a mid-plane of the cell (Fig. 3A,B; Movies 1–4) or total fluorescence within a plane that included mostly plasma membrane (Fig. 3C,D) (see Materials and Methods). In wild-type neurons, thapsigargin significantly increased the amount of STIM detected near the plasma membrane. This redistribution of STIM was attenuated in neurons with mutant IP3R (itprS224F/G1891S) (Fig. 3C,D). Store depletion also increased the intensity of IP3R immunostaining near the plasma membrane (Fig. 3A–D). There was no significant redistribution of IP3R in thapsigargin-treated neurons expressing mutant IP3R (Fig. 3A,B). Thapsigargin stimulated formation of STIM puncta in neurons expressing STIM–YFP (Fig. 3E), although the puncta were not detected with endogenous STIM. This is consistent with the effects of store depletion in mammalian cells, where STIM puncta are typically observed after overexpression of tagged STIM. The formation of STIM–YFP puncta after store depletion was significantly attenuated in Drosophila neurons with mutant IP3Rs (itprS224F/G1891S); and siRNA for the IP3R appeared to have a similar effect (Fig. 3E,F). The translocation of STIM and wild-type IP3R towards the plasma membrane after store depletion was not due to a general reorganization of the ER because co-staining of neurons for STIM and another ER protein (GFP-tagged protein disulphide isomerase, PDI–GFP) revealed that only STIM redistributed after thapsigargin treatment (Fig. S4). These results demonstrate that IP3R and STIM accumulate in peripheral ER near the plasma membrane after store depletion, and loss of IP3R or mutations within it inhibits the translocation of STIM.

Fig. 3.

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate translocation of IP3R and STIM after store depletion. (A) Typical confocal images across the mid-plane of fixed neurons immunostained for IP3R after treatment with thapsigargin (TG, 10 µM in Ca2+-free HBM for 10 min). Fluorescence profiles are shown below each image. (B) Summary results for peripheral IP3R immunostaining as a fraction of total cellular fluorescence for the indicated genotypes. The same colour key applies to panels B, D and F. (C) Optical section at the plasma membrane of neurons expressing mutant (itprS224F/G1891S) or WT IP3R with and without thapsigargin-treatment showing immunostaining for Orai and STIM or IP3R. (D) Summary results for near-plasma-membrane STIM and IP3R labelling (near-plasma membrane/total). (E) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and optical section of GFP fluorescence at plasma membrane of neurons expressing STIM–YFP with mutant (itprS224F/G1891S) or after treatment with siRNA to IP3R. The effects of treatment with thapsigargin are shown. (F) Summary results for the number of STIM–YFP puncta/cell. In B, D and F, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the 10–90th percentiles. Outliers are represented by dots. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Wilcoxon signed-rank post-hoc test [>50 cells from at least five independent experiments (B,D); >200 cells from at least five independent experiments (F)]. Scale bars: 5 µm.

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate formation of Orai puncta at the plasma membrane

Using an antibody to endogenous Orai, we observed that depletion of Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin stimulated formation of Orai puncta in neurons expressing wild-type IP3R, but not in neurons expressing mutant IP3Rs (itprS224F/G1891S) (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the sparse Orai puncta that did form in neurons with mutant IP3Rs were both smaller and less intensely stained than in neurons with wild-type IP3Rs (Fig. 4B–D). Overexpression of STIM had no effect on the formation of Orai puncta in neurons with either genotype, although it partially restored SOCE (Fig. 1D). However, after overexpression of both STIM and Orai, store depletion stimulated formation of Orai puncta that were similar in neurons with wild-type or mutant IP3Rs (Fig. 4B–D). The ability of overexpressed STIM and Orai to rescue formation of Orai puncta in neurons with mutant IP3Rs coincides with a similar rescue of SOCE in mutant neurons (Fig. 1D) and of flight in flies with mutant IP3R (Fig. S3A,B). These results suggest that overexpression of STIM with Orai can override the requirement of IP3R for formation of Orai puncta or SOCE after store depletion. However, when STIM and Orai are expressed at native levels in Drosophila, the interaction between them, the formation of Orai puncta and the activation of SOCE are enhanced by IP3R.

Fig. 4.

Mutant IP3Rs attenuate clustering of Orai after store depletion. (A) Typical confocal images from neurons with or without thapsigargin (TG) treatment and immunostained for endogenous Orai. The effects of the mutant IP3R combination (S224F/G1891S, red boxes), and overexpression of STIM alone (STIM+) or with Orai (STIM+Orai+) are shown. Scale bar: 5 µm. The representative confocal images show z-stacks of the deconvoluted sections. Each section was analysed individually for the summary analyses. (B–D) Summary data for the number of puncta/cell (B), intensity of fluorescence within puncta (C) and size of puncta (D). The colour key applies to all three panels. In B–D, the box represents the 25–75th percentiles, and the median is indicated. The whiskers show the 10–90th percentiles. Outliers are represented by dots. **P<0.01, Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Wilcoxon signed-rank post-hoc test (>150 cells from at least three independent experiments).

DISCUSSION

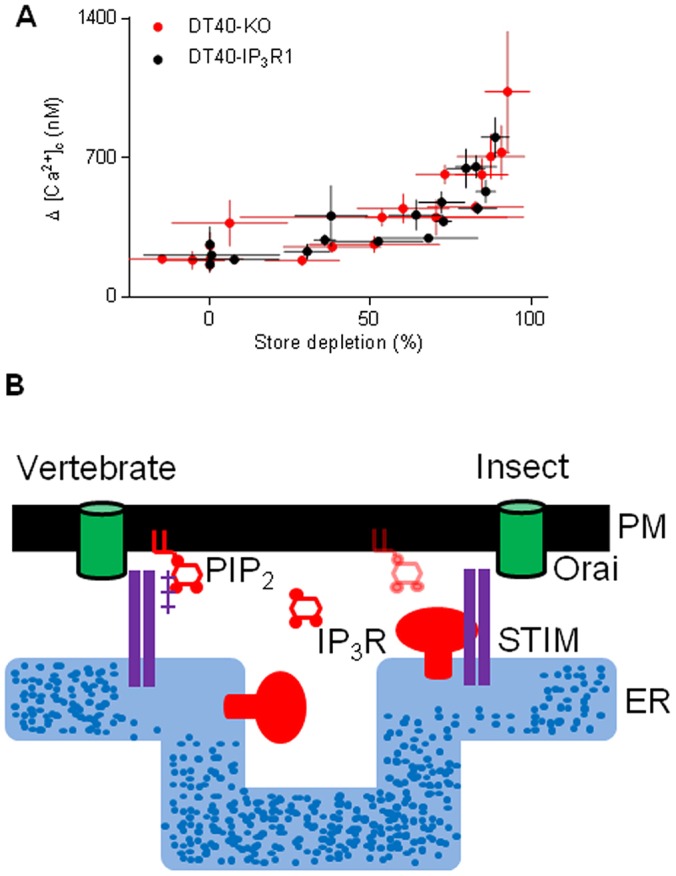

Before STIM was identified as the Ca2+ sensor that regulates SOCE, IP3Rs were speculated to adopt this role (Irvine, 1990). However, thapsigargin evokes SOCE in avian DT40 cells lacking IP3Rs (Sugawara et al., 1997) (Fig. 5A) and SOCE can be functionally reconstituted with Orai and STIM (Zhou et al., 2010). IP3Rs are not, therefore, essential for empty Ca2+ stores to activate SOCE. Our results, showing that SOCE is attenuated in Drosophila neurons with mutant IP3Rs (Fig. 1), suggest that IP3Rs can modulate SOCE. Depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores caused STIM and mutant IP3Rs to accumulate near the plasma membrane (Fig. 3A–F), STIM and Orai to associate (Fig. 2), formation of STIM and Orai puncta (Figs 3 and 4), and activation of SOCE (Fig. 1). These responses were attenuated in neurons with mutant IP3Rs. The effects of mutant IP3Rs were not due to a dominant-negative property of the mutants because SOCE was also attenuated when IP3Rs expression was reduced by siRNA (Fig. 1D) (Agrawal et al., 2010) and the mutant IP3Rs reduced SOCE only when both alleles were mutated (Fig. 1D). We suggest that after store-depletion, both STIM and IP3R translocate to ER–plasma-membrane junctions, where IP3R might stabilize the interaction of STIM with Orai, and thereby promote SOCE (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Coordination of store depletion and SOCE in insects and vertebrates. (A) DT40-KO or DT40-IP3R1 cells were incubated with different concentrations of a reversible inhibitor of the ER Ca2+ pump, cyclopiazonic acid (CPA, 0.1–3 µM) for 15 min in Ca2+-free HBS. In parallel wells, the peak increase in [Ca2+]c evoked by ionomycin (1 µM, to determine the Ca2+ content of the intracellular stores) or restoration of extracellular Ca2+ (1.5 mM, to determine SOCE) were measured. Results (means±s.e.m., n=3, with three replicates in each) show the relationship between store depletion and SOCE for the two cell lines. (B) Substantial loss of Ca2+ from the ER causes STIM to cluster and assemble with Orai at ER–plasma-membrane junctions. The polybasic cytoplasmic tail of vertebrate STIM1 binds to PIP2 within the plasma membrane and contributes to its targeting to junctions. Drosophila STIM lacks a PIP2-binding motif, but, after store-depletion, Drosophila STIM moves to ER–plasma-membrane junctions, and so too does IP3R where it might bind to PIP2. Physiological stimuli, through IP3, probably trigger the large decrease in luminal [Ca2+] needed to activate STIM1 in only a subset of the ER. Targeting of vertebrate STIM1 to plasma membrane enriched in the PIP2, from which IP3 is synthesized, ensures that the machinery needed to locally deplete Ca2+ stores remains closely associated with essential components of the SOCE pathway. We speculate that in Drosophila, association of IP3R with STIM and Orai at ER–plasma-membrane junctions might fulfil a similar role.

In some mammalian cells, IP3Rs have been shown to colocalize with Orai1 (Lur et al., 2011) and to interact with STIM1, Orai1 and transient receptor potential canonical channels (TRPCs) (Hong et al., 2011), but there is no functional evidence that IP3Rs directly contribute to SOCE mediated by Orai. Block of SOCE by an antagonist of IP3Rs, 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB), was originally suggested to reflect IP3R coupling to a SOCE channel (Ma et al., 2000), but it is now attributed to direct inhibition of STIM and Orai by 2-APB. However, most analyses of SOCE use thapsigargin to completely deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores, and overexpressed proteins to track movements of Orai and STIM. These exaggerated conditions successfully identify key features of SOCE, but they might override more subtle modulatory influences, including, for example, the contribution of PIP2 to recruitment of STIM1 to ER–plasma-membrane junctions (Hogan, 2015; Park et al., 2009). We used DT40 cells with and without IP3R1 (encoded by itpr1) and examined SOCE after graded depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores to assess whether partially depleted stores might more effectively activate SOCE in the presence of IP3R. However, the relationship between store depletion and SOCE was unaffected by expression of IP3R1 (Fig. 5A). Hence, there is no compelling evidence to suggest that the contribution of IP3R to SOCE in Drosophila is a feature shared with vertebrates.

Inhibition of Orai clustering in Drosophila neurons with mutant IP3Rs is reminiscent of the effects of septin depletion in mammalian cells. Septin 4 concentrates PIP2 around Orai1 and facilitates recruitment of STIM1 through its polybasic cytoplasmic tail (Sharma et al., 2013). Assembly of STIM–Orai complexes at PIP2-enriched plasma membrane domains concentrates the complexes at regions best equipped to sustain production of the IP3 that evokes Ca2+ release from stores. Such colocalization of Ca2+ release and SOCE might be important because activation of SOCE by physiological stimuli probably requires substantial local depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Bird et al., 2009; Luik et al., 2008). However, Drosophila STIM lacks the polybasic tail through which mammalian STIM1 binds to PIP2 (Huang et al., 2006). Association of Drosophila STIM with IP3R, which might itself bind to PIP2 (Lupu et al., 1998), could serve a function analogous to PIP2-mediated targeting of STIM1 in mammals. Recent evidence demonstrating a link between Septin 7, IP3R and SOCE (Deb et al., 2016) suggests that IP3R might influence STIM–Orai interactions within a larger macromolecular complex. We speculate that interaction of mammalian STIM1 with PIP2 might ensure that intracellular stores locally depleted of Ca2+ by IP3 are effectively localized to STIM–Orai complexes (Fig. 5B). Translocation of both IP3R and STIM to ER–plasma-membrane junctions after store depletion, where IP3R facilitates the interaction of STIM with Orai, might fulfil a similar role in Drosophila (Fig. 5B).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila strains

Single-point mutants of the itpr gene were characterized as described previously (Joshi et al., 2004; Srikanth et al., 2004). UAS transgenic strains were generated by injecting Drosophila embryos with a pUAST construct. All fly strains, including ElavC155GAL4 (pan neuronal, Bloomington Stock Center, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN), and RNAi lines for itpr (no. 1063, National Institute of Genetics, Japan), STIM (no. 47073) and Orai (no. 12221) were procured from the Vienna Drosophila Resource Centre, Austria. The Canton-S strain was used as the wild-type control.

Measurements of [Ca2+]c in primary cultures of Drosophila neurons

Materials, unless stated otherwise, were from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Methods for primary cultures were adapted from Wu et al. (1983). The brain and ventral ganglia from Drosophila third-instar larvae were dissociated by incubation for 20 min at 25°C in Schneider's medium containing collagenase (0.75 µg/µl) and dispase (0.4 µg/µl, Roche, Burgess Hill, UK). After centrifugation (600 g for 5 min), cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips in HEPES-buffered medium [HBM, in mM: HEPES (30), NaCl (150), KCl (5), MgCl2 (1), CaCl2 (1), sucrose (35), pH 7.2] or (for most experiments) Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with F12 and Glutamax-I, NaHCO3 and sodium pyruvate, and supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) and 10% fetal bovine serum. This enriched medium substantially reduced the heterogeneity of the Ca2+ signals between neurons. All culture media contained 50 units/ml penicillin, 50 µg/ml streptomycin and 10 µg/ml amphotericin B. Cells were incubated at 25°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. After 14–16 h, cells were loaded with fluo 4 by incubation at 25°C for 30 min with fluo 4-AM (2.5 µM) and Pluronic F-127 (0.02%) in HBM. Medium was then replaced with HBM, and after a further 10–30 min, with Ca2+-free HBM containing 0.5 mM EGTA. Cells were immediately imaged at 15-s intervals with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 520 nm using a Nikon TE2000 microscope with a 60×1.4 NA objective, Evolution QEi CCD camera and QED imaging software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). Background fluorescence (measured from an area without cells) was subtracted from all measurements before calculation of ΔF/F0, where F0 is the initial fluorescence and ΔF is the difference between basal and peak fluorescence.

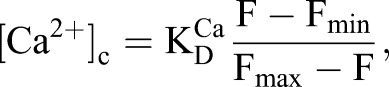

Measurements of SOCE in DT40 cells

Avian DT40 cells in which endogenous IP3R genes are disrupted (DT40-KO cells) (Sugawara et al., 1997) or the same cells stably expressing rat IP3R1 (DT40-IP3R1) were used to determine the contribution of IP3R to SOCE in cells from vertebrates. DT40 cells (107 cells/ml) were loaded with fluo-4 by incubation at 20°C with fluo-4 AM (2 µM) in HBS containing BSA (1 mg/ml) and Pluronic F-127 (0.02% w/v) [HBS in mM: NaCl (135), KCl (5.8), MgCl2 (1.2), CaCl2 (1.5), HEPES (11.6), d-glucose (11.5) pH 7.3]. After 60 min, cells were centrifuged (650 g, 2 min), re-suspended in HBS (5×106 cells/ml) and distributed (50 µl/well) into poly-l-lysine-coated half-area 96-well plates. After centrifugation (300 g, 2 min) fluorescence (excitation 485 nm, emission 525 nm) was recorded at 1.44-s intervals at 20°C in a FlexStation 3 plate-reader. Fluorescence signals (F) were calibrated to [Ca2+]c from:

|

(1) |

where, Fmin and Fmax are the fluorescence values determined in parallel wells by addition of Triton X-100 (0.1% w/v) and either BAPTA (10 mM) for Fmin, or CaCl2 (10 mM) for Fmax, and KDCa=345 nM.

Immunoprecipitation, western blotting and immunocytochemistry

For immunoprecipitation analyses, neuronal cultures were stimulated, washed and lysed in cold PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1% NP-40 and 5 mM EDTA, Roche protease inhibitor tablet and 10 µM MG-132. The lysate was homogenized by passage through a 26 G needle, mixed (30 min, 4°C) and after centrifugation (14,000 g, 20 min), the supernatant (0.5 µg protein/µl in PBS) was incubated with Dynabeads (2 mg) bound to anti-GFP antibody (15 µg, #A-11122). After 18–20 h at 4°C, the beads were washed and lysed according to the manufacturer's protocol, and used for western blotting. The antibodies used were: Drosophila STIM (1:10; Abexome, Bangalore, India) (Agrawal et al., 2010), GFP (1:5000; #SC9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) and α-tubulin (1:5000; #E7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, IA). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit-IgG (#32260; Thermo Scientific), anti-mouse-IgG (#7076S; Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) and anti-rat-IgG (#012030003; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) secondary antibodies were used and visualized with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate. For immunostaining, methods were adapted from Wegener et al. (2004). Cultured neurons were treated with thapsigargin and then fixed (30 min, 25°C, 3.5% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS), washed three times (PBS with 0.5% BSA, 0.05% Triton X-100 and 0.05% glycerol) and permeabilized (1 h, PBS with 5% BSA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5% glycerol). Cells were incubated for 12 h with primary antibody [rabbit for Drosophila IP3R (1:300) (Srikanth et al., 2004), mouse for Drosophila STIM (1:10) (Agrawal et al., 2010) and rat for Drosophila Orai (1:1000) (Pathak et al., 2015)]. Cells were then washed, incubated (30 min, 4°C) with appropriate secondary antibody (1:500) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (#A1108; Thermo Scientific), Alexa Fluor 594 (#20185) or Alexa Fluor 633 (#A201948) and washed. Images were acquired using an Olympus laser-scanning FV1000 SPD confocal microscope with 60×1.3 NA oil immersion objective. All images were corrected for background by subtraction of fluorescence recorded outside the cell.

Image analysis

Confocal images were deconvoluted using Huygens 4.5 software (SVI, The Netherlands) as described previously (Deb et al., 2016). To quantify the peripheral fluorescence of immunostained IP3R in each neuron, most of which have a near-circular profile (Fig. 3A), an automated algorithm (Matlab) was used to identify the confocal section with the maximal perimeter. Within this section, which we describe as the ‘mid-section’, the centre of the cell was identified and an average radius calculated (r). Fluorescence intensities were then calculated for the central circular region (with r/2) and for the remaining peripheral annulus. The ratio (peripheral fluorescence to total fluorescence) was then used to report the redistribution of IP3R.

To quantify near-plasma-membrane immunostaining of STIM and IP3R, we used Orai immunostaining to manually identify the confocal section within which most plasma membrane apposed the coverslip (Fig. 3C). The fluorescence intensity within this optical section relative to that from the entire cell was used to report the near-plasma-membrane distribution.

To quantify the distribution of STIM–YFP (Fig. 3G,H) and Orai (Fig. 4) puncta, every confocal section (∼15 sections/cell) was analysed (Deb et al., 2016). Puncta were identified automatically (Matlab) as fluorescence spots that exceeded average cellular fluorescence by at least 1.9× the s.d. and occupied a square with sides of 1–12 pixels (1 pixel=103 nm×103 nm) with a circularity of 0–0.3. Analysis of sequential sections within the z-stack allowed non-redundant counting of puncta, from which the total number of puncta/cell was determined. The section in which a punctum had the brightest intensity was used for analysis, and then normalized to the mean intensity of Orai for the cell.

Statistical analysis

Most data were analysed using non-parametric methods (Kruskal–Wallis test for variance followed by Wilcoxon signed-rank post-hoc tests). These data are presented as box and whisker plots showing medians, 25–75th percentiles (boxes), 10–90th percentiles (whiskers) and points for values beyond the 10th and 90th percentiles. Student's t-tests were used for statistical analysis of western blots (Fig. 2B) and Ca2+ signals in DT40 cells (Fig. 5A).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Central Imaging and Flow Cytometry Facility (NCBS), Dr R. Roy (Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore) for immunostaining protocols, B. Ramalingam (NCBS) for help with Matlab and Dr S. Ziegenhorn (NCBS) for UASdOrai-CFP transgenic lines.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

S.C., B.K.D. and T.C. performed experiments with Drosophila. V.K. performed experiments with DT40 cells. S.C., G.H. and. C.W.T. designed and interpreted experiments, analysed data and wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Funding

The work was supported by funding from National Centre for Biological Sciences, India to G.H.; Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, India to G.H.; and by the Wellcome Trust [grant number 101844 to C.W.T.]. S.C. and B.K.D. were supported by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India (CSIR) fellowships. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/jcs.191585.supplemental

References

- Agrawal N., Venkiteswaran G., Sadaf S., Padmanabhan N., Banerjee S. and Hasan G. (2010). Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor and dSTIM function in Drosophila insulin-producing neurons regulates systemic intracellular calcium homeostasis and flight. J. Neurosci. 30, 1301-1313. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3668-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Lee J., Venkatesh K., Wu C.-F. and Hasan G. (2004). Loss of flight and associated neuronal rhythmicity in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mutants of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 24, 7869-7878. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0656-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G. S., Hwang S.-Y., Smyth J. T., Fukushima M., Boyles R. R. and Putney J. W. Jr (2009). STIM1 is a calcium sensor specialized for digital signaling. Curr. Biol. 19, 1724-1729. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.08.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Choi S., Maleth J. J., Park S., Ahuja M. and Muallem S. (2015). The ER/PM microdomain, PI(4,5)P2 and the regulation of STIM1-Orai1 channel function. Cell Calcium 58, 342-348. 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco S. and Meyer T. (2011). STIM proteins and the endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 973-1000. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061609-165311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb B. K., Pathak T. and Hasan G. (2016). Store-independent modulation of Ca2+ entry through Orai by Septin 7. Nat. Commun. 7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11751 10.1038/ncomms11751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan P. G. (2015). The STIM1-ORAI1 microdomain. Cell Calcium 58, 357-367. 10.1016/j.ceca.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J. H., Li Q., Kim M. S., Shin D. M., Feske S., Birnbaumer L., Cheng K. T., Ambudkar I. S. and Muallem S. (2011). Polarized but differential localization and recruitment of STIM1, Orai1 and TRPC channels in secretory cells. Traffic 12, 232-245. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01138.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X., Pedi L., Diver M. M. and Long S. B. (2012). Crystal structure of the calcium release-activated calcium channel Orai. Science 338, 1308-1313. 10.1126/science.1228757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G. N., Zeng W., Kim J. Y., Yuan J. P., Han L., Muallem S. and Worley P. F. (2006). STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, Icrac and TRPC1 channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1003-1010. 10.1038/ncb1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine R. F. (1990). “Quantal” Ca2+ release and the control of Ca2+ entry by inositol phosphates - a possible mechanism. FEBS Lett. 263, 5-9. 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80692-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R., Venkatesh K., Srinivas R., Nair S. and Hasan G. (2004). Genetic dissection of itpr gene function reveals a vital requirement in aminergic cells of Drosophila larvae. Genetics 166, 225-236. 10.1534/genetics.166.1.225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis R. S. (2012). Store-operated calcium channels: new perspectives on mechanism and function. Cold Spring Harb. Persp. Biol. 3, a003970. 10.1101/cshperspect.a003970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luik R. M., Wang B., Prakriya M., Wu M. M. and Lewis R. S. (2008). Oligomerization of STIM1 couples ER calcium depletion to CRAC channel activation. Nature 454, 538-542. 10.1038/nature07065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupu V. D., Kaznacheyeva E., Krishna U. M., Falck J. R. and Bezprozvanny I. (1998). Functional coupling of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14067-14070. 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lur G., Sherwood M. W., Ebisui E., Haynes L., Feske S., Sutton R., Burgoyne R. D., Mikoshiba K., Petersen O. H. and Tepikin A. V. (2011). InsP3 receptors and Orai channels in pancreatic acinar cells: co-localization and its consequences. Biochem. J. 436, 231-239. 10.1042/BJ20110083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H.-T., Patterson R. L., van Rossum D. B., Birnbaumer L., Mikoshiba K. and Gill D. L. (2000). Requirement of the inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Science 287, 1647-1651. 10.1126/science.287.5458.1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C. Y., Hoover P. J., Mullins F. M., Bachhawat P., Covington E. D., Raunser S., Walz T., Garcia K. C., Dolmetsch R. E. and Lewis R. S. (2009). STIM1 clusters and activates CRAC channels via direct binding of a cytosolic domain to Orai1. Cell 136, 876-890. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak T., Agrawal T., Richhariya S., Sadaf S. and Hasan G. (2015). Store-operated calcium entry through Orai is required for transcriptional maturation of the flight circuit in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 35, 13784-13799. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1680-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney J. W. and Tomita T. (2012). Phospholipase C signaling and calcium influx. Adv. Enzyme Reg. 52, 152-164. 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2011.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S., Quintana A., Findlay G. M., Mettlen M., Baust B., Jain M., Nilsson R., Rao A. and Hogan P. G. (2013). An siRNA screen for NFAT activation identifies septins as coordinators of store-operated Ca2+ entry. Nature 499, 238-242. 10.1038/nature12229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth S. and Gwack Y. (2012). Orai1, STIM1, and their associating partners. J. Physiol. 590, 4169-4177. 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.231522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth S., Wang Z., Tu H., Nair S., Mathew M. K., Hasan G. and Bezprozvanny I. (2004). Functional properties of the Drosophila melanogaster inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor mutants. Biophys. J. 86, 3634-3646. 10.1529/biophysj.104.040121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara H., Kurosaki M., Takata M. and Kurosaki T. (1997). Genetic evidence for involvement of type 1, type 2 and type 3 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in signal transduction through the B-cell antigen receptor. EMBO J. 16, 3078-3088. 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G. and Hasan G. (2009). Intracellular Ca2+ signaling and store-operated Ca2+ entry are required in Drosophila neurons for flight. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 10326-10331. 10.1073/pnas.0902982106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener C., Hamasaka Y. and Nassel D. R. (2004). Acetylcholine increases intracellular Ca2+ via nicotinic receptors in cultured PDF-containing clock neurons of Drosophila. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 912-923. 10.1152/jn.00678.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. F., Suzuki N. and Poo M. M. (1983). Dissociated neurons from normal and mutant Drosophila larval central nervous system in cell culture. J. Neurosci. 3, 1888-1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. M., Covington E. D. and Lewis R. S. (2014). Single-molecule analysis of diffusion and trapping of STIM1 and Orai1 at endoplasmic reticulum-plasma membrane junctions. Mol. Biol. Cell 25, 3672-3685. 10.1091/mbc.E14-06-1107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Meraner P., Kwon H. T., Machnes D., Oh-hora M., Zimmer J., Huang Y., Stura A., Rao A. and Hogan P. G. (2010). STIM1 gates the store-operated calcium channel ORAI1 in vitro. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 112-116. 10.1038/nsmb.1724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]