Abstract

When treated with nerve growth factor, PC12 cells will differentiate over the course of several days. Here, we have followed changes during differentiation in the cellular levels of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) and its activator, Gαq, which together mediate Ca2+ release. We also followed changes in the level of the novel PLCβ binding partner TRAX (translin-associated factor X), which promotes RNA-induced gene silencing. We find that the level of PLCβ increases 4-fold within 24 h, whereas Gαq increases only 1.4-fold, and this increase occurs ∼24 h later than PLCβ. Alternately, the level of TRAX remains constant over the 72 h tested. When PLCβ1 or TRAX is down-regulated, differentiation does not occur. The impact of PLCβ on differentiation appears independent of Gαq as down-regulating Gαq at constant PLCβ does not affect differentiation. Förster resonance energy transfer studies after PLCβ association with its partners indicate that PLCβ induced soon after nerve growth factor treatment associates with TRAX rather than Gαq. Functional measurements of Ca2+ signals to assess the activity of PLCβ-Gαq complexes and measurements of the reversal of siRNA(GAPDH) to assess the activity of PLCβ-TRAX complexes additionally suggest that the newly synthesized PLCβ associates with TRAX to impact RNA-induced silencing. Taken together, our studies show that PLCβ, through its ability to bind TRAX and reverse RNA silencing of specific genes, plays a key role in switching PC12 cells to their differentiated state.

Keywords: calcium intracellular release, cell differentiation, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), G protein, Phospholipase C

Introduction

Differentiation of cells to a neuronal phenotype is a complex process involving a series of genetic and morphological changes. PC12 cells, which are derived from a pheochromocytoma of the rat adrenal medulla, have an embryonic origin from the neural crest (1) and are often used as model systems to study neural differentiation. PC12 cells are highly proliferative in their undifferentiated state. When treated with nerve growth factor (NGF), proliferation ceases and differentiation begins as seen by the onset of neurite growth as well as accumulation of Ca2+ vesicles (2). NGF binds to TrkA growth factor receptors (3, 4) leading to changes in transcription of a number of proteins that are associated with the differentiated state (5). Differentiation of PC12 cells is generally considered complete when the length of the neurites is three-four times the length of the cell body. One set of proteins that are associated with the differentiated state are those that control acetylcholine, serotonin, and dopamine pathways that lead to increased intracellular calcium (i.e. members of the G-protein/phospholipase Cβ signaling pathway) (6).

Our laboratory has actively studied the Gαq/PLCβ2 signaling system (e.g. Refs. 7–9). This pathway is activated by many types of neurotransmitters and hormones such as acetylcholine, dopamine, angiotensin II, bradykinin, etc. (10, 11). Binding of these ligands to their specific G protein-coupled receptor results in the activation of Gαq (GTP) that in turn stimulates the ability of PLCβ to catalyze the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate, which ultimately results in the release of intracellular Ca2+ from stores in the endoplasmic reticulum. PLCβ (β1–4) enzymes vary in their tissue distribution and their ability to be activated by Gαq. This study focuses on PLCβ1 as it is strongly activated by Gαq, is highly expressed in neural tissue, and can shuttle between the plasma membrane, cytosol, and nucleus (12–15).

In PC12 cells PLCβ1 is primarily found on the plasma membrane in a complex with Gαq, in addition to the cytoplasm and the nucleus (16). Recently, we made the surprising discovery that cytosolic PLCβ binds to the promoter of RNA-induced silencing, C3PO (17). Additionally, we found that the association of PLCβ to C3PO reverses the RNA-induced silencing of specific genes, such as GAPDH (8). Further studies using purified proteins suggested that this specificity results from the ability of PLCβ to inhibit the activity of C3PO toward substrates that are rapidly hydrolyzed (18). Because the binding region of C3PO on PLCβ enzymes directly overlaps with the Gαq binding site, C3PO competes with Gαq for PLCβ. Thus, whereas C3PO does not affect the basal activity of PLCβ, it prevents its activation by Gαq (8, 17).

C3PO crystallizes as an octamer containing 6 molecules of the single-stranded DNA/RNA-binding protein translin and 2 molecules of the nuclease translin-associated factor X (TRAX) (19). The expression of translin and TRAX are closely linked (20). Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that PLCβ binds to an external site on either one or both of the TRAX subunits to inhibit TRAX activity (18). In addition to playing a role in tRNA processing, C3PO has also been shown to promote RNA-induced gene silencing by promoting the degradation of the passenger strand of duplex silencing RNA to allow hybridization of the target mRNA to the guide strand of the interfering RNA (21).

Although we have gathered ample evidence that PLCβ binds to C3PO, the biological significance of this interaction has remained unclear. We have evidence that PLCβ can shuttle between Gαq on the plasma membrane and C3PO in the cytoplasm (22). Activation of Gαq reduces the association between PLCβ to C3PO, whereas treatment of cells with siRNA attenuates PLCβ-mediated Ca2+ signals (23), leading to the idea that the impact of PLCβ1 on RNA silencing may be related to the relative levels of the two PLCβ binding partners C3PO and Gαq. In this study we show that the initial stages of differentiation of PC12 cells depends on increased association between PLCβ and C3PO rather than between PLCβ and Gαq. Thus, the ability of PLCβ to modulate RNA silencing through its association with C3PO demonstrates that this unexpected secondary function of PLCβ plays a role in certain physiological processes.

Results

Differentiation Induces Large Changes in the Cellular Levels of PLCβ1 and Gαq at Different Rates but Not TRAX

In their undifferentiated state, PC12 cells have a spherical morphology. Upon NGF treatment, the cells begin to sprout neurites within a few hours. Differentiation is generally considered complete when the length of the neurites is three times the length of the cell body. Under our conditions, we find that the ratio of the length of the neurites versus the length of the body reaches 3.0 ∼36 h after NGF treatment under our conditions.

We followed the changes in expression of PLCβ1, TRAX, and Gαq as a function of time after NFG is added to PC12 cells to initiate differentiation. Interestingly, we found a marked increase in the level of PLCβ1 (i.e. 2.5–2.7-fold) in first 24 h. This increase peaks to 4-fold at 48 h (Fig. 1A) and decreases thereafter. Although Gαq also showed a large increase in expression with differentiation (1.6-fold), the onset of this increase was delayed 24 h relative to PLCβ (Fig. 1A). The levels of Gαq began to decline after 48 h but still remained higher than in the undifferentiated state (Fig. 1A). In contrast to PLCβ1 and Gαq, no changes in the level of TRAX, and in turn C3PO (20), were observed over 72 h after NGF treatment (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

A, changes in the cellular levels of PLCβ1, Gαq, and TRAX in PC12 cells after the addition of NGF as determined by Western blotting where protein levels were normalized to loading control (β-actin) and where the data were compiled from six independent experiments. Changes in TRAX were found to not be significant, but changes in PLCβ1 and Gαq at 48 and 72 h were significant compared with undifferentiated conditions (p < 0.001). Also shown on the right is a sample Western blot where UN refers to undifferentiated PC12 cells. B, increases in the membrane-associated PLCβ1 in PC12 cells where membrane fractions were isolated as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and the amount of enzyme was divided by the total cellular level of PLCβ1. The data were compiled from three separate experiments, and a sample Western blot is shown. All points on the graph are statistically different (p < 0.001).

Although we have only observed Gαq on the plasma membrane in PC12 cells (16), PLCβ has been identified in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and the plasma membrane (15, 16). We wanted to determine whether the increase in PLCβ that occurs with differentiation localizes to the plasma membrane or other compartments. These studies were done by assessing the amount of endogenous enzyme found in the whole cell by Western blotting and comparing it to the level found in the membrane fractions. We note that PLCβ1 in the cytosol is too dilute to accurately quantify. We find that 24 h after NGF treatment, when PLCβ production is highest, the level of membrane-bound PLCβ corresponds to approximately half the newly produced PLCβ (Fig. 1B). However, at 48 h, when Gαq levels peak, almost all of the enzyme is associated with the membrane fraction. These results suggest that half of the newly synthesized enzyme remains in the cytosol until enough available Gαq is made.

Down-regulation of PLCβ and TRAX, but Not Gαq, Prevents Differentiation

Based on the large increases in the levels of PLCβ and Gαq with differentiation, we tested the idea that eliminating the expression of PLCβ would prevent differentiation. PLCβ was down-regulated by ∼80% using siRNA 24 h before treatment with NGF. We find that cells transfected with siRNA (PLCβ1) did not differentiate as assessed by a lack of neurite growth over 72 h of NGF treatment (Fig. 2, A and B).

FIGURE 2.

A, images of PC12 cells 24 h after NGF treatment where cells were treated with various reagents as noted 24 h before NGF addition. B, graph showing the change in the ratio of neurite to body length for cells under various treatments 24 h after NGF treatment where 30 points were taken over 2–5 separate experiments and p ≤ 0.001. C, top, Western blot showing the effect of down-regulating Gαq and PLCβ1 by siRNA treatment on the expression of other proteins where the lines note the specific treatment. This study was reproduced four times in independent experiments. Bottom, Western blot showing the effect of down-regulation of Gαq and TRAX on PLCβ1 levels where each of the samples were run on five lanes as indicated by the line above the lanes.

To determine whether the lack of differentiation caused by PLCβ1 down-regulation is due to its ability to mediate G protein signals, we repeated the study down-regulating Gαq. Because down-regulating Gαq also reduced the expression of PLCβ1 (Fig. 2C), we cotransfected PLCβ1 with siRNA(Gαq) to maintain a constant level of PLCβ (see Fig. 2C) and measured differentiation. We find that the cells differentiated normally (Fig. 2, A and B), suggesting that Gαq is not involved in differentiation.

We then tested the role of TRAX on differentiation and note that down-regulation of TRAX down-regulates translin and hence C3PO (see Ref. 20). We also note that down-regulating TRAX does not affect PLCβ1 expression (Fig. 2C). Similar to the results seen for PLCβ1, down-regulating TRAX blocks PC12 cell differentiation (Fig. 2, A and B). Taken together, these results suggest that PLCβ and C3PO, either together or in isolation, play a key role in PC12 cell differentiation.

PLCβ Changes Its Association with Its Gαq and TRAX Binding Partners during Differentiation

To test whether the association between TRAX and PLCβ1 was one of the factors that prevented PC12 cells differentiation, we followed the association of PLCβ to TRAX and also to Gαq after NGF treatment using Főrster resonance energy transfer (FRET) (see Ref. 16). We first examined changes in the relative number of eCFP-Gαq/eYFP-PLCβ1 complexes, which based on the results above, are not expected to affect differentiation. We note that FRET is a ratiometric quantity, and in order to obtain accurate FRET values we viewed cells in which the donor and acceptor intensities were within a factor of 10, which should not bias the results (see Ref. 25). Measurements were limited to the plasma membrane region where Gαq is localized, and this was verified by the absence of PLCβ-Gαq FRET in the cytoplasm. The results are shown in Fig. 3, A and B. We find little change in FRET from 0 to 24 h after the addition of NGF, suggesting that the amount of PLCβ-Gαq FRET is unchanged. This result suggests that the increased cellular amount of PLCβ that is produced during this time does not result in an increase in the number of PLCβ-Gαq complexes. At 48 h, where the level of Gαq sharply rises, we find a large population of fluorescent-tagged proteins is not associated with PLCβ, which may reflect initial association of the newly synthesized Gαq still being trafficked to the plasma membrane as noted by the observation of the protein in cytosolic endosomes or not in optimal orientation for productive FRET. However, as the levels of Gαq on the plasma membrane rise at 72 h, the level of FRET reaches a higher value consistent with previous studies (8).

FIGURE 3.

A, raw images of undifferentiated and differentiated PC12 cells expressing eCFP-TRAX (left), eYFP-PLCβ1 (middle), and the corresponding FRET image (right) for the two sets of images. B, changes in FRET values of eCFP-Gαq and eYFP-PLCβ1 expressed in PC12 cells where n = 30 from 4 independent experiments. 48 and 72 h are statistically significant (p = 0.008 and p < 0.001, respectively). In these studies, FRET for the negative control (i.e. free CFP and free YFP) equaled 0.008 ± 0.005, and FRET for the positive control (eCFP-X12-eYFP) equaled 0.432 ± 0.024. C, similar FRET study monitoring changes in eCFP-TRAX and eYFP-PLCβ1 where n = 30 over 4 independent experiments and p < 0.001. UN, undifferentiated PC12 cells. D, Western blot showing the levels of PLCβ1, Gαq, and TRAX during PC12 cell differentiation when eYGP-PLCβ1 is overexpressed before NGF treatment.

We used the same FRET approach to monitor changes in the association between PLCβ and TRAX with differentiation in the cytosol where the majority of the complexes have been identified (17, 23). Upon NGF treatment, we observed an ∼2-fold increase in the amount of FRET (14.2 ± 0.08 to 28.2 ± 0.09% (p < 0.001) when normalized to positive and negative controls) in the first 12 h and a reduction in FRET thereafter (Fig. 3C). We note that the increase in association at 12 h rather than 24 reflects the higher initial level of PLCβ due to overexpression of the fluorescent construct (see Fig. 3D).

Changes in the Relative Levels of Gαq and TRAX with Differentiation Affect Ca2+ Signals and RISC Activity

We measured changes in Ca2+ responses through the Gαq-PLCβ pathway in undifferentiated cells and after NGF treatment. These studies were carried out by stimulating a suspension of cells (106 cells/ml) loaded with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator (Fura-2) with carbachol. We find that the amount of Ca2+ released at 0 and 24 h after NGF treatment were similar to each other and lower than the amount released at 48 h (Fig. 4). This behavior parallels the increase in Gαq levels with differentiation.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in Ca2+ release with stimulation of Gαq/PLCβ by 5 μm carbachol in undifferentiated PC12 cells and after NGF treatment. Measurements were taken of 30–45 single cells loaded with Ca2+ Green and analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

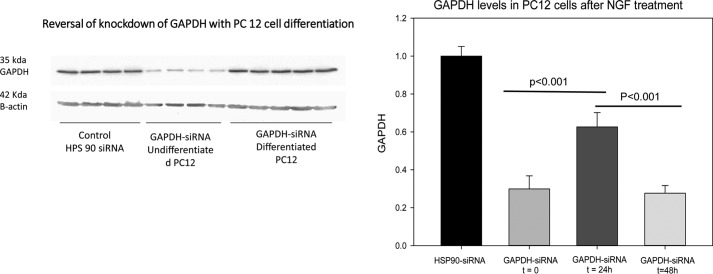

We have previously shown that overexpression of PLCβ1 can reverse down-regulation of specific proteins through its association with C3PO (8). We tested reversal in siRNA down-regulation of GAPDH and compared these results to an siRNA for a message that PLCβ1 is not able to reverse (siRNA(Hsp90)). The results (Fig. 5) show that at 24 h after NGF treatment, when the PLCβ1 levels are high but Gαq levels are low, the ability of PLCβ1 to reverse down-regulation of GAPDH by siRNA is significantly less efficient, whereas Hsp90 levels are unaffected. However, when Gαq levels rise to drive PLCβ binding, as seen by an increased calcium response, the ability of PLCβ to reverse C3PO activity is greatly reduced. These studies show that higher PLCβ levels impacts on RISC activity through its association with TRAX.

FIGURE 5.

Levels of GAPDH in undifferentiated PC12 cells treated with either siRNA(Hsp90) as a control or with siRNA(GAPDH) and then 24 and 48 h after NGF treatment. The band intensities of GAPDH were normalized to β-actin loading controls. n = 8 over 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study we show that PLCβ and TRAX are required for PC12 cell differentiation. This finding demonstrates that the ability of PLCβ to inhibit TRAX may play a key biological role in specific cellular functions. Previously, PLCβ enzymes were not thought to impact differentiation. Instead, changes in phosphatidylinositide signals during differentiation were found to be initiated by PLCγ subsequent to activation of TrkA receptors upon NGF treatment (see Ref. 26). It is notable that the Ca2+ released by PLCγ activity in turn stimulates the highly active PLCδ synergizing the calcium signal. The very high specific activity of PLCδ as compared with PLCβ upon NFG treatment, especially at low Gαq concentrations, suggests that PLCβ would contribute little, if any, to phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate hydrolysis and the Ca2+ levels. This observation supports the idea that PLCβ's traditional role as the main effector of Gαq does not impact differentiation.

It has been established that PLCβ1 levels correlate closely with neuronal differentiation in both cat and rat somatosensory cortex (27), establishing a role of PLCβ1 in brain development. Therefore, it is not surprising that large increases of both Gαq and PLCβ levels are associated with PC12 cell differentiation as the cells establish sensory Ca2+ signaling pathways. However, it was surprising to find that a very large increase in PLCβ expression occurs before the onset of increased Gαq levels. This finding correlates well with the idea that the phosphoinositide lipid signaling function of PLCβ does not appear to play a role in the initial stages of differentiation, as indicated by the lack of effect of Gαq down-regulation.

Our studies suggest that the increase in PLCβ levels and the relative changes in its two binding partners coordinate to allow PC12 cell differentiation. PLCβ levels increased 24 h before Gαq, and the newly synthesized enzyme interacts with TRAX as observed by FRET studies showing an increase in the number of PLCβ-TRAX complexes. However, this increase in FRET reverses at 48 h, which correlates to the increased level of Gαq. Localization studies at these later times show a large increase in the membrane-bound population of PLCβ consistent with the idea that it is being driven to the membrane and away from TRAX as Gαq is synthesized and more PLCβ1 binding sites become available. Although we expected to observe an increase in FRET between Gαq and PLCβ at 48 h, we instead find a strong contribution of weakly transferring species. This low FRET population may be due to either uncomplexed protein or proteins in an orientation where the probability of FRET is reduced. Previous diffusion studies of PLCβ in PC12 cells 48 h after NGF treatment show a very limited mobility (16), indicating that PLCβ is associated with slower moving species (presumably Gαq). Thus, at 48 h after NGF treatment PLCβ may be driven to the membrane by Gαq but not in close enough proximity to the protein or in a favorable orientation for FRET. In any event, our results suggest that the delayed synthesis of new Gαq competes with TRAX for PLCβ until the final differentiated state is reached. The idea that differentiation proceeds through changes in the number of PLCβ-TRAX versus PLCβ-Gαq complexes can be seen in studies where we overexpressed Gαq to drive PLCβ from TRAX, and we find that differentiation no longer occurs.

Previous studies have suggested that PLCβ is not involved in PC12 cell differentiation (28). However, in those studies, the importance of PLCβ was assessed by over-expressing the enzyme, and here we also show that over-expressing PLCβ does not affect differentiation. Instead, we find that a minimal amount of PLCβ is needed to interact with TRAX and drive differentiation. This idea is supported by the absolute need for TRAX in the differentiation process. The observation that excess PLCβ neither diminishes nor promotes this process suggests that there is a limited number of TRAX binding sites for PLCβ.

C3PO has been reported to play a role in tRNA processing and promote mRNA degradation by the RNA-induced silencing complex (17, 19, 21). Like PLCβ1, TRAX also is associated with neuronal development (24). Thus, the finding that TRAX, which is responsible for C3PO nuclease activity, is required for PC12 cell differentiation was not unexpected. We have previously shown that PLCβ binds to the TRAX subunits of C3PO and inhibits its activity (18). Thus, it is possible that in the undifferentiated state, C3PO helps to transiently silence specific genes that interfere with the progression of cells into the differentiated state. Our studies showing the reversal of siRNA(GAPDH) silencing at 24 h, when the levels of Gαq are low and PLCβ binding to TRAX is promoted, correlate well with this idea. After this initial period, as more Gαq is synthesized, PLCβ dissociates from TRAX and presumably moves to the plasma membrane to carry out its traditional role in G protein signaling as differentiation is completed. In this way, PLCβ acts as an off/on switch to inhibit the transcription of genes that interfere with differentiation. We are in the process of identifying the specific genes.

Experimental Procedures

PC12 Cell Culture and Differentiation

PC12 cells were purchased from American Tissue Cell Culture and cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) with 10% horse serum from PAA (Ontario, Canada), 5% FBS (Atlanta Biological, Atlanta, GA), and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were incubated in 37 °C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity. Differentiation was carried out in a medium of 1% horse serum, 0.5% FBS, 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin and was initiated by the addition of nerve growth factor (NGF 7S) from Sigma. Medium was changed every 24 h.

Western Blotting

Samples were placed in 6-well plates and collected in 250 μl of lysis buffer that included Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors. After SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, protein bands were transfer to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Primary antibodies to PLCβ1 (D-8), Gαq (E-17), and TRAX (E-11) were from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX). Antibodies for β-actin and GAPDH from were from Abcam. Membranes were treated with antibodies diluted 1:1000 in 0.5% dry milk and washed 3 times for 5 min before applying secondary antibiotic (anti-mouse or anti-goat from Santa Cruz) at a concentration of 1:500. Membranes were washed 3 times for 5 min before imaging on a Bio-Rad imager to determine the band intensities. Bands were measured at several sensitivities to ensure the intensities were in a linear range. Data were analyzed using Image J in grayscale plot profile. Bands were normalized to loading control.

Transfection

Plasmid transfections were accomplished using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Transfection of siRNAs was also carried out using Lipofectamine 3000.

Transfection for FRET Studies

Cells were seeded in 35-ml dishes. At 60% confluence cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 with 1 μl of DNA of the target protein according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were given 3 days to express the fluorescent proteins. Four separate samples were prepared: empty vectors, donor alone, acceptor alone, and both donor and acceptor.

Plasma Membrane Isolation

1 × 107 cells were collected and homogenized manually. Trypan blue was used to check the quality of homogenization. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 4 °C for 3 min at 4000 rpm to isolate nuclei. The supernatant was collected and subjected to ultracentrifugation at 45,000 rpm for 45 min to separate the cell membrane.

Confocal Imaging

Cells were seeded in poly-d-lysine-coated glass-covered dishes from Mat-Tek. Images were acquired on an Olympus Fluorview 1000 confocal microscope and Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope. Data were analyzed using Olympus Fluoview 1000 software and Image J software.

Calcium Measurements

Single cell calcium measurements were carried out by labeling the cells with calcium green (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in incubated in HBSS for 45 min and washed twice with HBSS before imaging. Ensemble calcium measurements were carried out by preparing cells in 100-ml dishes, washing with HBSS, harvesting, and labeling with Fura-2 (Invitrogen) for 45 min in HBSS with 1% BSA and 5 mm glucose. Cells were washed twice, adjusted to a count of 1 × 106 cells/ml, and placed in 1-ml cuvettes. Cells were stimulated with 1 μm carbachol. Calcium range was determined by disrupting cells by 10% Triton X-100 and by 200 mm EDTA to chelate calcium.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Sigma Plot 11 statistical packages that included Student's t test and one way analysis of variance.

Author Contributions

O. G. carried out the experimental work and analysis. S. S. helped with experimental design, data analysis, and the writing of this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Imanol Gonzàlez-Burguera for initiating this study, Simon Haleguoa for advice, and Giuseppe Caso and Yuanjian Guo for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1GM116187 and RO172853. This work was also supported by the Richard Whitcomb endowment. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- TRAX

- translin-associated factor X

- HBSS

- Hanks' balanced salt solution

- RISC

- RNA-induced silencing complex

- eCFP

- enhanced cyano fluorescent protein

- eYFP

- enhanced yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1. Greene L. A., and Tischler A. S. (1976) Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 73, 2424–2428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Das K. P., Freudenrich T. M., and Mundy W. R. (2004) Assessment of PC12 cell differentiation and neurite growth: a comparison of morphological and neurochemical measures. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 26, 397–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Toni T., Dua P., and van der Graaf P. H. (2014) Systems Pharmacology of the NGF Signaling Through p75 and TrkA Receptors. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 3, e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marchetti L., De Nadai T., Bonsignore F., Calvello M., Signore G., Viegi A., Beltram F., Luin S., and Cattaneo A. (2014) Site-specific labeling of neurotrophins and their receptors via short and versatile peptide tags. PloS ONE 9, e113708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klesse L. J., Meyers K. A., Marshall C. J., and Parada L. F. (1999) Nerve growth factor induces survival and differentiation through two distinct signaling cascades in PC12 cells. Oncogene 18, 2055–2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Westerink R. H., and Ewing A. G. (2008) The PC12 cell as model for neurosecretion. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 192, 273–285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drin G., and Scarlata S. (2007) Stimulation of phospholipase Cβ by membrane interactions, interdomain movement, and G protein binding: how many ways can you activate an enzyme? Cell. Signal. 19, 1383–1392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Philip F., Sahu S., Caso G., and Scarlata S. (2013) Role of phospholipase Cβ in RNA interference. Adv. Biol. Regul. 53, 319–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weinstein H., and Scarlata S. (2011) The correlation between multidomain enzymes and multiple activation mechanisms: the case of phospholipase Cβ and its membrane interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808, 2940–2947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rebecchi M. J., and Pentyala S. N. (2000) Structure, function, and control of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C. Physiol. Rev. 80, 1291–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Suh P. G., Park J. I., Manzoli L., Cocco L., Peak J. C., Katan M., Fukami K., Kataoka T., Yun S., and Ryu S. H. (2008) Multiple roles of phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C isozymes. BMB Rep. 41, 415–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berstein G., Blank J. L., Jhon D. Y., Exton J. H., Rhee S. G., and Ross E. M. (1992) Phospholipase Cβ1 is a GTPase-activating protein for Gq/11, its physiologic regulator. Cell 70, 411–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ciruela A., Hinchliffe K. A., Divecha N., and Irvine R. F. (2000) Nuclear targeting of the β isoform of type II phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase) by its α-helix 7. Biochem. J. 346, 587–591 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cocco L., Martelli A. M., Vitale M., Falconi M., Barnabei O., Stewart Gilmour R., and Manzoli F. A. (2002) Inositides in the nucleus: regulation of nuclear PI-PLCβ1. Adv. Enzyme Regul. 42, 181–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aisiku O., Dowal L., and Scarlata S. (2011) Protein kinase C phosphorylation of PLCβ1 regulates its cellular localization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 509, 186–190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dowal L., Provitera P., and Scarlata S. (2006) Stable association between Gαq and phospholipase Cβ1 in living cells. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 23999–24014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Aisiku O. R., Runnels L. W., and Scarlata S. (2010) Identification of a novel binding partner of phospholipase Cβ1: translin-associated factor X. PloS ONE 5, e15001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sahu S., Philip F., and Scarlata S. (2014) Hydrolysis Rates of different small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) by the RNA silencing promoter complex, C3PO, determines their regulation by phospholipase Cβ. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5134–5144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ye X., Huang N., Liu Y., Paroo Z., Huerta C., Li P., Chen S., Liu Q., and Zhang H. (2011) Structure of C3PO and mechanism of human RISC activation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 650–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang S., Cho Y. S., Chennathukuzhi V. M., Underkoffler L. A., Loomes K., and Hecht N. B. (2004) Translin-associated factor X is post-transcriptionally regulated by its partner protein TB-RBP, and both are essential for normal cell proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12605–12614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Y., Ye X., Jiang F., Liang C., Chen D., Peng J., Kinch L. N., Grishin N. V., and Liu Q. (2009) C3PO, an endoribonuclease that promotes RNAi by facilitating RISC activation. Science 325, 750–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Philip F., Sahu S., Golebiewska U., and Scarlata S. (2016) RNA-induced silencing attenuates G protein-mediated calcium signals. FASEB J. 30, 1958–1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Philip F., Guo Y., Aisiku O., and Scarlata S. (2012) Phospholipase Cβ1 is linked to RNA interference of specific genes through translin-associated factor X. FASEB J. 26, 4903–4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li Z., Wu Y., and Baraban J. M. (2008) The Translin/Trax RNA binding complex: clues to function in the nervous system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1779, 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Golebiewska U., Johnston J. M., Devi L., Filizola M., and Scarlata S. (2011) Differential response to morphine of the oligomeric state of μ-opioid in the presence of δ-opioid receptors. Biochemistry 50, 2829–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim U. H., Fink D. Jr., Kim H. S., Park D. J., Contreras M. L., Guroff G., and Rhee S. G. (1991) Nerve growth factor stimulates phosphorylation of phospholipase Cγ in PC12 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 1359–1362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hannan A. J., Kind P. C., and Blakemore C. (1998) Phospholipase C-β1 expression correlates with neuronal differentiation and synaptic plasticity in rat somatosensory cortex. Neuropharmacology 37, 593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bortul R., Aluigi M., Tazzari P. L., Tabellini G., Baldini G., Bareggi R., Narducci P., and Martelli A. M. (2001) Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase Cβ1 expression is not linked to nerve growth factor-induced differentiation, cell survival or cell cycle control in PC12 rat pheocromocytoma cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 84, 56–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]