Abstract

Nucleobase radicals are major products of the reactions between nucleic acids and hydroxyl radical, which is produced via the indirect effect of ionizing radiation. The nucleobase radicals also result from hydration of cation radicals that are produced via the direct effect of ionizing radiation. The role that nucleobase radicals play in strand scission has been investigated indirectly using ionizing radiation to generate them. More recently, the reactivity of nucleobase radicals resulting from formal hydrogen atom or hydroxyl radical addition to pyrimidines has been studied by independently generating the reactive intermediates via UV-photolysis of synthetic precursors. This approach has provided control over where the reactive intermediates are produced within biopolymers and facilitated studying their reactivity. The contributions to our understanding of pyrimidine nucleobase radical reactivity by this approach are summarized.

Keywords: nucleic acid damage, radicals, reactive intermediates, reaction mechanism

Nucleic acid damage resulting from molecular oxidants that bind noncovalently to the biopolymer is typically ascribed to hydrogen atom abstraction from one or more positions of the (deoxy)ribose component.1–4 Some of the carbohydrate radicals result in direct strand breaks, while others give rise to lesions that yield strand breaks upon subsequent alkali treatment (alkali-labile lesions). The reactivity preference of hydroxyl radical (HO•), which is produced from H2O by ionizing radiation (the indirect effect) and the metal complex, Fe•EDTA is very different.5–7 Nucleobase radicals resulting from π-bond addition are the major family of reactive intermediates generated from HO•. Ionization of nucleic acids by γ-radiolysis, photosensitization, or chemical agents (e.g. persulfate radical anion) yields the formal HO• nucleobase adducts following H2O trapping. Pyrimidines and purines react via these processes, but reaction of HO• with the latter is less well understood, and recent publications concerning purine radical reactivity are at odds with previous reports. This review focuses on pyrimidine nucleobase radical adduct reactivity. Central questions regarding the reactivity of these molecules concern their transformation into strand breaks, tandem lesions, as well as their interconversion, particularly with respect to the dehydration and formal rearrangement of HO• adducts. A variety of tools have been applied to address these questions, including computational methods and organic photochemistry to independently generate the putative reactive intermediates.

The preference for HO• addition to nucleobase π-bonds versus carbohydrate hydrogen atom abstraction is consistent with kinetic studies on model systems.8 Some reports indicate that HO• addition to nucleobase π-bonds account for more than 90% of the reactions between this reactive oxygen species and pyrimidine nucleos(t)ides. While this may be an overestimation, the consensus is that nucleobase adducts are the major products formed between HO• and pyrimidines. Reports on the regioselectivity of HO• addition (e.g. 1, 2) also vary, and depend somewhat on the particular pyrimidine, but C5-addition is favored.5, 9–11 Hydroxyl radical adducts also form from hydration of nucleobase radical cations (e.g. 3, Scheme 1). Hydration occurs selectively at the C6-position formally yielding the C6-hydroxyl radical adduct. (Radical cation 3 also undergoes deprotonation at the methyl group to form 5-(2′-deoxyuridin)methyl radical.12–14) Hydroxyl radical regioselectivity is also potentially complicated via the rearrangement of the initially formed radical adducts from one to another.

Scheme 1.

Direct and indirect formation of HO• radical adducts.

The formal HO• nucleobase adducts (e.g. 1, 2) and pyrimidine radical cations (e.g. 3) have been proposed to ultimately yield strand breaks by abstraction hydrogen atoms from the (2′-deoxy)ribose backbone in DNA and RNA. Elegant experiments using random generation of the reactive intermediates via photolysis and γ-radiolysis were used in conjunction with a myriad of techniques including mass spectrometric product analysis, EPR spectroscopy to detect radicals, and laser light scattering to detect strand breaks in a time dependent manner.

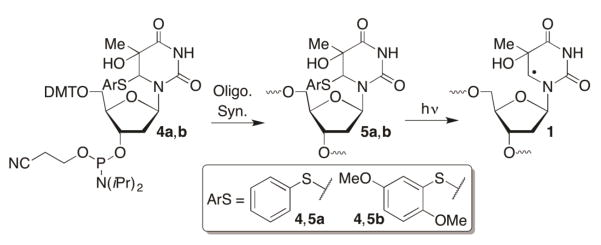

Independent generation of nucleobase radical adducts. Indiscriminate generation of reactive intermediates via γ-radiolysis or UV-irradiation makes determining the reactive of individual species more challenging. During the past two decades several pyrimidine nucleobase radicals have been generated photochemically from synthetic precursors. (Please note that photochemical precursors and nucleobase radicals are referred to using the same descriptor whether they are nucleosides or present in oligonucleotides.) These precursors have been used to examine reactivity of monomeric species and at site specific positions within oligonucleotides by introducing the appropriately functionalized (phosphoramidite, e.g. 4) monomers via solid phase synthesis (Scheme 2). The C5-thymidine HO• adduct (1 from 5, Scheme 2) has been studied using this approach, as have a number of formal hydrogen atom addition adducts of pyrimidine 2′-deoxy- and ribonucleosides.15–26 Norrish Type I cleavage of ketones (7, 10, 12, 14) has been the most common strategy (Scheme 3), although aryl sulfides (5) and phenyl selenides (8) have also been used (Schemes 2, 3). In several investigations the formal hydrogen atom adducts were generated. Although the respective alkyl radicals produced upon HO• addition are expected to be slightly more reactive (electrophilic), the corresponding hydrogen atom adduct precursors are typically more accessible synthetically.27, 28 The monomeric C5-hydroxyl radical adduct of thymidine (1) has also been generated via photoinduced single electron transfer from 15 (eqn. 1), but this method cannot be used in the biopolymer.29

Scheme 2.

Direct and indirect formation of HO• radical adducts.

Scheme 3.

Independent generation of pyrimidine nucleobase radicals.

|

Eqn. 1 |

Dehydration and rearrangement of hydroxyl radical adducts. The yield and rate of direct strand breaks formed upon γ-irradiation of poly(U) increases as the pH is decreased.30 The rate constant for strand scission was reported to increase from ~1 s−1 to ~100 s−1 upon reducing the pH from 6.5 to 3.4. One explanation put forth to explain this phenomenon is that initially formed hydoxyl radical adduct(s) (16, 17) dehydrate to the cation radical (18), which then either adds water to yield a regioisomeric HO• adduct or directly abstracts a hydrogen atom from the carbohydrate backbone (H•abs) in RNA (Scheme 4).30–32 Electron donation by the C5-methyl group in 1 was expected to yield greater dehydration rates compared to the HO• adduct in uridine. However, no evidence for dehydration from 1 was obtained when it was produced from 15.29 The rate constant for dehydration was estimated using competitive kinetics to be less than 2 s−1, which based upon the rate constant noted above does suggests that this process is unlikely but does not rule it out as a source for direct strand scission.

Scheme 4.

Dehydration of HO• radical adducts.

Sevilla and Adhikary demonstrated that 1 does isomerize to 2 at less than 0 °C on the scale of minutes.33 However, this is in glasses at alkaline pH 9 at which the imido proton on thymidine is removed. Furthermore, even a timescale of minutes is far too long to compete with other radical processes that 1 undergoes in solution.

The transformation of nucleobase radicals into direct strand breaks and tandem lesions. Trapping of nucleobase radicals with O2 and/or reducing agents yields a range of products that are interesting in their own right.34–36 Some of these molecules (DNA lesions) are potent blocks of replication or are bypassed in an error prone manner.37–42 This review focuses on hydrogen atom abstraction by the nucleobase radicals and their O2 trapping products from their own carbohydrate component (intranucleotidyl) or carbohydrate backbone of proximal nucleotides (internucleotidyl). Hydrogen atom abstraction from the carbohydrate backbone is required but not necessarily sufficient for direct strand scission from a nucleobase radical.

In RNA, analysis of independent experiments suggested that nucleobase radicals must result give rise to some direct strand breaks. γ-Radiolysis experiments revealed that 40% of the reactions between HO• and RNA result in strand scission and a minimum of 80% of HO• reactions occur with the nucleobases.43, 44 These data suggest that at least 20% of the nucleobase (peroxyl) radicals must abstract a hydrogen atom from the carbohydrate backbone. Nucleobase derived strand scission in DNA is significantly less efficient. Elegant experiments involving the irradiation of DNA plasmids indicated that ≤5% of nucleobase (peroxyl) radicals give rise to direct strand breaks.45 Earlier product analyses by mass spectrometry on thymidine and oligomers of various length provided inferential support that thymine radicals must react with the carbohydrate backbones within polymers.46

Various positions on the DNA and RNA carbohydrate backbones have been suggested as sites of hydrogen atom abstraction by nucleobases.10, 11, 31, 32, 47–49 However, given the large differences in strand break efficiency in DNA and RNA, the C2′-position in the latter stands out as a prime candidate for reaction. Computational studies indicated that the bond dissociation energy (BDE) of the C2′-carbon-hydrogen bond in RNA (~86 kcal/mol) is several kcal/mol lower than any other carbon-hydrogen bond in the backbone of RNA or DNA.50 The weakest carbon-hydrogen bond in DNA (C5′-carbon-hydrogen) was predicted to have a BDE > 91 kcal/mol. The weaker C2′-carbon-hydrogen bond in RNA than DNA was also evident in computational studies on barriers of intranucleotidyl hydrogen atom abstraction.27, 28, 51, 52 Barriers for C2′-hydrogen atom abstraction by a nucleobase radical in ribonucleotides ranged between ~14–16 kcal/mol; whereas reactions at the respective position in DNA were > 19 kcal/mol. In addition, hydrogen atom abstraction from the C1′-, C2′-, or C3′-position of a 5′-adjacent nucleotide by a nucleobase peroxyl radical is predicted to incur an even greater barrier (> 20 kcal/mol).53 In the absence of a clear energetically favorable hydrogen atom abstraction pathway, other computation studies have focused on the reaction of DNA nucleobase peroxyl radicals with adjacent nucleobases to form tandem lesions.54 Peroxyl radical addition to the double bonds of adjacent nucleotides is favored in the 5′-direction and the most readily oxidized nucleobase, guanine, is the most reactive.

The reactivity of independently generated pyrimidine nucleobase radicals in DNA. The aforementioned γ-radiolysis experiments and computational studies were mostly affirmed upon independent generation of 1, 6, or 9. In the absence of O2 1, 6, or 9 do not lead to direct strand breaks or alkali-labile lesions, consistent with the ≥19 kcal/mol barrier predicted for hydrogen atom abstraction.15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 24, 51, 52 Direct strand breaks were detected at the 5′-adjacent nucleotide when the 5,6-dihydrothymidin-5-yl radical (6) was produced under aerobic conditions.15, 17 However, the direct strand break yield is very low. Isotopic labeling of the 5′-adjacent nucleotide was used to probe the site(s) of hydrogen atom abstraction. C4′-Deuteration or C2′-dideuteration had no effect on strand scission, suggesting that peroxyl radical 19 did not abstract hydrogen atoms from these positions (Scheme 5). In contrast, deuteration of the C1′-position of the 5′-adjacent nucleotide reduced strand scission ~4-fold.15 The observed direct strand scission could have been an artifact of sample handling, as C1′-oxidation typically produces alkali-labile 2-deoxyribonolactone (20).55–57 Product analysis of photolysis of a dinucleotide (8) provided additional support for internucleotidyl C1′-hydrogen atom abstraction by 19. Photoysis of 8 under aerobic conditions produced the tandem lesion containing 2-deoxyribonolactone (20) in low yield (Scheme 5).18

Scheme 5.

Tandem lesion formation from 5,6-dihydrothymidin-5-yl radical (6).

The C6-radicals 1 (Scheme 2) and 9 (Scheme 3) generated a variety of tandem lesions but direct strand scission was not detected under aerobic conditions.19, 22, 24 Evidence for tandem lesion formation upon irradiation had been obtained previously by mass spectrometry.58–60 The tandem lesions were detected by gel electrophoresis following alkali treatment, as well as by mass spectrometry. The peroxyl radical of the formal C5-hydrogen atom adduct of 2′-deoxyuridine (21) produces tandem lesions by reacting with the 5′- and 3′-adjacent nucleobases (Scheme 6). As was observed in experiments involving 19 (Scheme 5) selective C1′-hydrogen atom abstraction from the 5′-adjacent nucleotide was detected. Reactivity with the carbohydrate component of the 3′-adjacent nucleotide was not detected. The observation of a significant 2H KIE (4.4 ± 0.1) when the C1′-position of the 5′-adjacent nucleotide was labeled, was augmented by product studies. Chemical fingerprinting using a series of reactions that are diagnostic for 2-deoxyribonolactone (L) was complemented by reaction with a biotinylated sensor that selectively tags L. 2-Deoxyribonolactone was also observed by mass spectrometric analysis of photolyzed single-stranded oligonucleotides containing 10.19, 22, 55, 61 2-Deoxyribonolactone was also detected by mass spectrometry at the original site of the radical.19 This product is believed to result from intranucleotidyl C1′-hydrogen atom abstraction.

Scheme 6.

Tandem lesion formation from 5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridin-6-yl peroxyl radical (21).

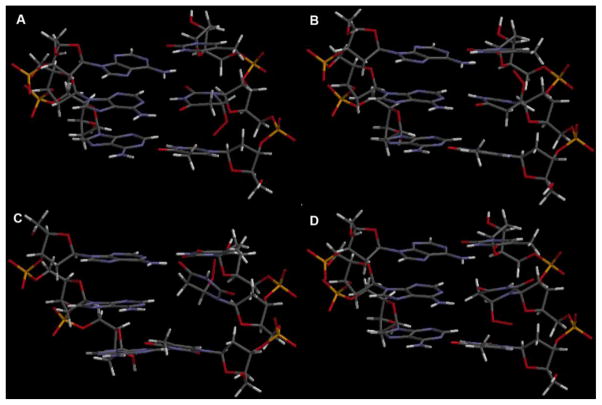

Competitive kinetic experiments indicated that the syn- and anti-conformations of 6R-21 and 6S-21 produce tandem lesions (Scheme 6) by reacting abstracting hydrogen atom(s) from the carbohydrate backbone and by adding to the adjacent nucleobase π-bonds.19, 20, 22 The distribution of tandem lesions is believed to depend on a combination of proximity and inherent selectivity of the radicals. For instance, peroxyl radical 21 selectively abstracts the C1′-hydrogen atom from the 5′-adjacent nucleotide. Molecular modeling indicates that the C1′-hydrogen atom on the 5′-adjacent nucleotide is within 1.3 Å of the radical center of anti-6R-21 and 1.5 Å of syn-6S-21 (Figure 1). In contrast, the lack of reactivity at the carbohydrate component of the 3′-adjacent nucleotide is consistent with the greater than 3 Å distance between syn-6R-21 or anti-6S-21 (~5.5 Å) and the corresponding C1′-hydrogen atom (Figure 1).22 The anti-6R-21 peroxyl radical is in a far more favorable position to react with the C1′-hydrogen atom (calculated BDE ~93.4 kcal/mol) on the 5′-adjacent nucleotide than the possibly weaker C5′-hydrogen atom (calculated BDE ~91.3 kcal/mol).50 The corresponding C2′-hydrogen atom is accessible but the carbon-hydrogen BDE (~97 kcal/mol) is considerably greater.

Figure 1.

Molecular modeling of duplex DNA containing 5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridin-6-yl peroxyl radical (21) in the sequence 5′-T•21•T/A•A•A. (A) anti-6R-21 (B) anti-6S-21 (C) syn-6R-21 (D) syn-6S-21.

Proximity effects aside, hydrogen atom abstraction from the carbohydrate backbone is a minor contributor to tandem lesion formation by peroxyl radical 21. Peroxyl radical addition to the π-bond of the 5′-adjacent nucleobase is the major pathway. Tandem lesions attributable to peroxyl radical addition to adjacent nucleotides were detected by mass spectrometry.19, 22 Consequently, incorporating 5,6-dihydrothymidine (dHT) at the 5′-adjacent nucleotide significantly reduced the contribution of piperidine-labile lesions that are indicative of nucleobase modifications at that position.22, 62 The rate constants for reaction of 21 with the 5′-adjacent nucleotide were estimated using glutathione (GSH) as a competitor. Reaction with the adjacent nucleotide was almost 30-times greater when dG (1.2 ± 0.2 × 10−1 s−1) was in that position than when dT (4.4 ± 0.6 × 10−3 s−1) was present.19, 24 These results are consistent with the more electron rich nature of dG and its relatively favorable oxidation potential compared to thymidine.63 Preferential reaction with dG is also consistent with computational studies on tandem lesion formation.54

The reactivity of the peroxyl radical (22, Scheme 7) of the C5-hydroxyl radical adduct of thymidine (1) was considerably different than that of 21.24 For instance, products resulting from hydrogen atom abstraction from the carbohydrate backbone, such as 2-deoxyribonolactone (23) were not detected. Furthermore, although tandem lesions were detected (e.g. 24, 25) by mass spectrometry, competitive kinetics revealed that 22 reacted more slowly than 21.64 This was true for the respective monomeric radical and peroxyl radicals, as well as when the latter was generated within oligonucleotides. Thymidine C5-hydroxyl radical adduct (1) reacted more than 10-fold less rapidly with β-mercaptoethanol (BME) (k = 4.7 – 5.7 ± 0.1 × 105 M−1s−1) than did 83 (k = 8.8 ± 0.5 × 106 M−1s−1).21, 23 Although the difference was smaller between the respective peroxyl radicals in oligonucleotides, 22 reacted with a 5′-adjacent dG (7.3 ± 0.9 × 10−2 s−1) approximately one-half as fast as did 21. The ability to monitor dG oxidation following independent generation of 22 was useful for testing a proposal that pyrimidine peroxyl radicals contribute to DNA electron transfer by oxidizing purine nucleotides.65 Outer sphere oxidation of dG by a DNA peroxyl radical was expected to be uphill by ~0.23 eV.63, 66 Although a variety of oxidation products from 22 were detected, examination of reactivity in a variety of duplex sequences that are frequently used to probe for electron transfer provided no evidence for this pathway.24, 67–69

Scheme 7.

Tandem lesion formation from 5,6-dihydro-thymidin-6-yl peroxyl radical (22).

The observed reactivity trend was surprising in one respect as the C5-hydroxyl group was expected to increase the electrophilicity of the radical. One possible reason as to why 22 (and 1) reacts more slowly and selectively than does 21 (and 9), is that disubstitution at C5 of the pyrimidine increases steric hindrance and/or disrupts base stacking making.24 The latter could increase the barrier for reaction between 22 and the 5′-adjacent nucleotide. Computational studies support the possibility that 5,6-dihydrothymidines that are disubstituted at C5 disrupt π-stacking.70, 71 However, additional studies of the type carried out by Dumont would be helpful.54

The reactivity of independently generated pyrimidine nucleobase radicals in RNA. The possible effects of sterics discussed above are not an issue in examining RNA nucleobase radical reactivity because of the absence of a C5-methyl group. Consequently, generating the formal C5- (11) and C6-hydrogen atom adducts (13) of uridine from the respective t-butyl ketones (12, 14, Scheme 3) instead of the true HO• adducts raises the possibility that the radicals studied are both less reactive due to the absence of the electronegative hydroxyl group.72–75 As expected from the work of Milligan and others (see above), direct strand breaks were observed 11 (Scheme 8) or 13 (Scheme 9) were generated under anaerobic conditions.44, 45, 72–74 Cleavage was observed at the 5′-adjacent nucleotide following generation of 11 or 13. The C6-radical (11) also yielded intranucleotidyl cleavage. Strand scission was as much as 4-fold more efficient in duplex RNA than in single stranded substrates.

Scheme 8.

Direct strand scission from the C5-hydrogen atom adduct of uridine (11) in RNA.

Scheme 9.

Direct strand scission from the C6-hydrogen atom adduct of uridine (13) in RNA.

The position of hydrogen atom abstraction by the nucleobase radicals was established by a series of diverse experiments that were consistent with expectations based upon calculated bond dissociation energies and accessibility.50 Large deuterium isotope effects were observed when the C2′-position of the 5′-adjacent nucleotide was labeled. Radical 13 yielded a KIE = 3.6 ± 0.7 but no effect when the C3′-position was deuterated.72 Cleavage at the 5′-adjacent nucleotide via 11 decreased more than 7-fold when deuterium was introduced at the C2′-position.74 Furthermore, the decrease in reactivity at this nucleotide was offset to some extent by increased intramolecular cleavage. This is consistent with competition between intranucleotidyl and internucleotidyl hydrogen atom abstraction (Scheme 8).

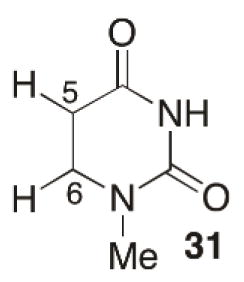

The deuterium isotope effects suggested strand cleavage from 11 and 13 proceeded through a common intermediate, C2′-radical 26. This was further supported by product analysis via by gel electrophoresis following chemical and enzymatic reactions of photolysates, and mass spectrometry, which revealed that 11 and 13 gave rise to common products (28–30, Scheme 8). The mechanism for strand scission was proposed to involve C2′-hydrogen atom abstraction (26), followed by rapid heterolytic cleavage of the 3′-phosphate (27, Scheme 8). The C5-radical (13, Scheme 9) abstracts the C2′-hydrogen atom from the 5′-adjacent nucleotide ~25-times faster than does 11.72, 73 This is consistent with computational experiments that suggest that the C5-carbon-hydrogen bond in N1-methyl-5,6-dihydrouracil (31) is ~2.8 kcal/mol stronger than the C6-carbon-hydrogen bond.72

|

Eqn. 2 |

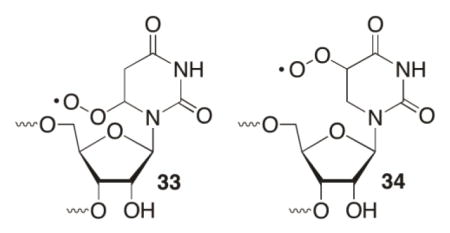

The viability of rapid phosphate cleavage from 26 was established by independently generating this species from benzyl ketone 32 (eqn. 2).76 Conservative estimates based upon competition studies indicate that the rate constant for strand scission is > 106 s−1. This rate constant is faster than O2 trapping, whose presence has no effect on strand scission from 26. Independent generation of 26 answered a number of questions concerning strand scission from 11 and 13. The rapid rate of cleavage from 26 revealed that selective strand scission under anaerobic conditions was due to greater reactivity of the alkyl radicals (11, 13) than the respective peroxyl radicals (33, 34) and that hydrogen atom abstraction by the nucleobase radicals is the rate determining step. How the radical cation is transformed into the final products is still uncertain.

Summary

By standing on the shoulders of radiation scientists, organic chemists have been able to provide additional insight into the reactivity of the major family of reactive intermediates produced in nucleic acids by ionizing radiation. Independent generation of nucleobase radicals has provided an explanation for the greater susceptibility of RNA than DNA to γ-radiolysis induced strand scission, and a greater understanding of tandem lesion formation in general. Investigations of purine radical intermediates via their independent generation are in the early stages but could provide valuable insight into this less well-understood family of radicals.77, 78 Independent generation of nucleobase radical cations is another pursuit that would enhance our understanding of radiation induced nucleic acid damage, which has not been carried out within biopolymers.

Highlights.

RNA nucleobase radicals abstract hydrogen atoms to yield direct strand breaks.

DNA nucleobase peroxyl radicals yield tandem lesions.

Dehydration of nucleobase hydroxyl radical adducts is slow.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to National Institute of General Medical Science (GM-054996) for support of this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burger RM. Cleavage of nucleic acids by bleomycin. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1153–1169. doi: 10.1021/cr960438a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xi Z, Goldberg IH. DNA-damaging enediyne compounds. In: Kool ET, editor. Comprehensive natural products chemistry. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1999. pp. 553–592. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigman DS, Mazumder A, Perrin DM. Chemical nucleases. Chem Rev. 1993;93:2295–2316. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bales BC, Pitié M, Meunier B, Greenberg MM. A minor groove binding copper-phenanthroline conjugate produces direct strand breaks via β-elimination of 2-deoxyribonolactone. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9062–9063. doi: 10.1021/ja026970z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.von Sonntag C. Free-radical-induced DNA damage and its repair. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Sonntag C. The chemical basis of radiation biology. Taylor & Francis; London: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pogozelski WK, McNeese TJ, Tullius TD. What species is responsible for strand scission in the reaction of [FeIIEDTA]2− and H2O2 with DNA? J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:6428–6433. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB. Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH, •O−) in aqueous solution. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1988;17:513–886. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner JR, Decarroz C, Berger M, Cadet J. Hydroxyl-radical-induced decomposition of 2′-deoxycytidine in aerated aqueous solutions. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:4101–4110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeble DJ, von Sonntag C. Radiolysis of poly(U) in oxygented solution. Int J Radiat Biol. 1986;49:927–936. doi: 10.1080/09553008514553161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeble DJ, Schulz D, von Sonntag C. Reactions of OH radicals with poly(U) in deoxygenated solutions: Sites of OH radical attack and the kinetics of base release. Int J Radiat Biol. 1986;49:915–926. doi: 10.1080/09553008514553151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanvah S, Joseph J, Schuster GB, Barnett RN, Cleveland CL, Landman U. Oxidation of DNA: Damage to nucleobases. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:280–287. doi: 10.1021/ar900175a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weng L, Horvat SM, Schiesser CH, Greenberg MM. Deconvoluting the reactivity of two intermediates formed from modified pyrimidines. Org Lett. 2013;15:3618–3621. doi: 10.1021/ol401472m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagner JR, van Lier JE, Berger M, Cadet J. Thymidine hydroperoxides: Structural assignment, conformational features, and thermal decomposition in water. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:2235–2242. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg MM, Barvian MR, Cook GP, Goodman BK, Matray TJ, Tronche C, Venkatesan H. DNA damage induced via 5,6-dihydrothymidin-5-yl in single-stranded oligonucleotides. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:1828–1839. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barvian MR, Greenberg MM. Independent generation of 5,6-dihydrothymid-5-yl and investigation of its ability to effect nucleic acid strand scission via hydrogen atom abstraction. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1916–1917. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barvian MR, Greenberg MM. Independent generation of 5,6-dihydrothymid-5-yl in single-stranded polythymidylate. O2 is necessary for strand scission. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8291–8292. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tallman KA, Greenberg MM. Oxygen-dependent DNA damage amplification involving 5,6-dihydrothymidin-5-yl in a structurally minimal system. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5181–5187. doi: 10.1021/ja010180s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong IS, Carter KN, Sato K, Greenberg MM. Characterization and mechanism of formation of tandem lesions in DNA by a nucleobase peroxyl radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4089–4098. doi: 10.1021/ja0692276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong IS, Carter KN, Greenberg MM. Evidence for glycosidic bond rotation in a nucleobase peroxyl radical and its effect on tandem lesion formation. J Org Chem. 2004;69:6974–6978. doi: 10.1021/jo0492158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter KN, Greenberg MM. Independent generation and study of 5,6-dihydro-2′-deoxyuridin-6-yl, a member of the major family of reactive intermediates formed in DNA from the effects of γ-radiolysis. J Org Chem. 2003;68:4275–4280. doi: 10.1021/jo034038g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter KN, Greenberg MM. Tandem lesions are the major products resulting from a pyrimidine nucleobase radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13376–13378. doi: 10.1021/ja036629u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.San Pedro JMN, Greenberg MM. Photochemical generation and reactivity of the major hydroxyl radical adduct of thymidine. Org Lett. 2012;14:2866–2869. doi: 10.1021/ol301109z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.San Pedro JMN, Greenberg MM. 5,6-Dihydropyrimidine peroxyl radical reactivity in DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:3928–3936. doi: 10.1021/ja412562p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Wang Y. The reactivity of the 5-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymidin-6-yl radical in oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1897–1906. doi: 10.1021/tx050195u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Q, Wang Y. Independent generation of the 5-hydroxy-5,6-dihydrothymidin-6-yl radical and its reactivity in dinucleoside monophosphates. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13287–13297. doi: 10.1021/ja048492t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Zhang R, Eriksson LA. The fate of H• atom adducts to 3′-uridine monophosphate. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:9617–9621. doi: 10.1021/jp100116w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang RB, Eriksson LA. Distinct hydroxy-radical-induced damage of 3 ′-uridine monophosphate in rna: A theoretical study. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:2394–2402. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barvian MR, Barkley RM, Greenberg MM. Reactivity of 5,6-dihydro-5-hydroxythymid-6-yl generated via photoinduced single electron transfer and the role of cyclohexa-1,4-diene in the photodeoxygenation process. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:4894–4904. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulte-Frohlinde D, Hildenbrand K. Electron spin resonance studies of the reactions of •OH and of SO4−• radicals with DNA, polynucleotides and single base model compounds. In: Minisci F, editor. Free Radicals in Synthesis and Biology. Kluwer; Dorderecht: 1989. pp. 335–359. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hildenbrand K, Behrens G, Schulte-Frohlinde D. Comparison of the reaction of •OH and of SO4−• radicals with pyrimidine nucleosides. An electron spin resonance study in aqueous solution. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans II. 1989:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Catterall H, Davies MJ, Gilbert BC. An EPR study of the transfer of radical-induced damage from the base to sugar in nucleic acid components: Relevance to the occurrence of strand-breakage. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans II. 1992:1379–1385. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adhikary A, Kumar A, Heizer AN, Palmer BJ, Pottiboyina V, Liang Y, Wnuk SF, Sevilla MD. Hydroxyl ion addition to one-electron oxidized thymine: Unimolecular interconversion of C5 to C6 OH-adducts. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:3121–3135. doi: 10.1021/ja310650n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: Induction, repair and significance. Mutat Res. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dizdaroglu M, Jaruga P. Mechanisms of free radical-induced damage to DNA. Free Rad Res. 2012;46:382–419. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.653969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner JR, Cadet J. Oxidation reactions of cytosine DNA components by hydroxyl radical and one-electron oxidants in aerated aqueous solutions. Acc Chem Res. 2010;43:564–571. doi: 10.1021/ar9002637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takata K-i, Shimizu T, Iwai S, Wood RD. Human DNA polymerase η (poln) is a low fidelity enzyme capable of error-free bypass of 5S-thymine glycol. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23445–23455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang H, Imoto S, Greenberg MM. The mutagenicity of thymidine glycol in escherichia coli is increased when it is part of a tandem lesion. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7833–7841. doi: 10.1021/bi900927d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aller P, Rould MA, Hogg M, Wallace SS, Doublie S. A structural rationale for stalling of a replicative DNA polymerase at the most common oxidative thymine lesion, thymine glycol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:814–818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606648104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fischhaber PL, Gerlach VL, Feaver WJ, Hatahet Z, Wallace SS, Friedberg EC. Human DNA polymerase k bypasses and extends beyond thymine glycols during translesion synthesis in vitro, preferentially incorporating correct nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37604–37611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basu AK, Loechler EL, Leadon SA, Essigmann JM. Genetic effects of thymine glycol: Site-specific mutagenesis and molecular modeling studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7677–7681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenberg MM, Matray TJ. Inhibition of klenow fragment (exo−) catalyzed DNA polymerization by (5r)-5,6-dihydro-5-hydroxythymidine and structural analogue 5,6-dihydro-5-methyltymidine. Biochemistry. 1997;36:14071–14079. doi: 10.1021/bi971630p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lemaire DGE, Bothe E, Schulte-Frohlinde D. Yields of radiation-induced main chain scission of poly U in aqueous solution: Strand break formation via base radicals. Int J Radiat Biol. 1984;45:351–358. doi: 10.1080/09553008414550491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hildenbrand K, Schulte-Frohlinde D. E.S.R. Studies on the mechanism of hydroxyl radical-induced strand breakage of polyuridylic acid. Int J Radiat Biol. 1989;55:725–738. doi: 10.1080/09553008914550781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milligan JR, Aguilera JA, Nguyen T-TD. Yield of DNA strand breaks after base oxidation of plasmid DNA. Radiat Res. 1999;151:334–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karam LR, Dizdaroglu M, Simic MG. Intramolecular H-atom abstraction from the sugar moiety by thymine radicals in oligo- and polydeoxynucleotides. Radiat Res. 1988;116:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones GDD, O’Neill P. Kinetics of radiation-induced strand break formation in single-stranded pyrimidine polynucleotides in the presence and absence of oxygen; a time-resolved light-scattering study. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991;59:1127–1145. doi: 10.1080/09553009114551031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones GDD, O’Neill P. The kinetics of radiation-induced strand breakage in polynucleotides in the presence of oxygen: A time-resolved light-scattering study. Int J Radiat Biol. 1990;57:1123–1139. doi: 10.1080/09553009014551241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolf P, Jones GDD, Candeias LP, O’Neill P. Induction of strand breaks in polyribonucleotides and DNA by the sulphate radical anion: Role of electron loss centres as precursors of strand breakage. Int J Radiat Biol. 1993;64:7–18. doi: 10.1080/09553009314551061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li MJ, Liu L, Wei K, Fu Y, Guo QX. Significant effects of phosphorylation on relative stabilities of DNA and RNA sugar radicals: Remarkably high susceptibility of H-2′ abstraction in RNA. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:13582–13589. doi: 10.1021/jp060331j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schyman P, Eriksson LA, Zhang Rb, Laaksonen A. Hydroxyl radical - thymine adduct induced DNA damages. Chem Phys Lett. 2008;458:186–189. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Rb, Eriksson LA. The role of nucleobase carboradical and carbanion on DNA lesions: A theoretical study. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:23583–23589. doi: 10.1021/jp063605b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schyman P, Eriksson LA, Laaksonen A. Hydrogen abstraction from deoxyribose by a neighboring 3′-uracil peroxyl radical. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6574–6578. doi: 10.1021/jp9007569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dupont C, Patel C, Ravanat JL, Dumont E. Addressing the competitive formation of tandem DNA lesions by a nucleobase peroxyl radical: A dft-d screening. Org Biomol Chem. 2013;11:3038–3045. doi: 10.1039/c3ob40280k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang J-T, Tallman KA, Greenberg MM. The reactivity of the 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion in single-stranded DNA and its implication in reaction mechanisms of DNA damage and repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3805–3810. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roupioz Y, Lhomme J, Kotera M. Chemistry of the 2-deoxyribonolactone lesion in oligonucleotides: Cleavage kinetics and products analysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9129–9135. doi: 10.1021/ja025688p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng Y, Sheppard TL. Half-life and DNA strand scission products of 2-deoxyribonolactone oxidative DNA damage lesions. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:197–207. doi: 10.1021/tx034197v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patrzyc HB, Dawidzik JB, Budzinski EE, Freund HG, Wilton JH, Box HC. Covalently linked tandem lesions in DNA. Radiat Res. 2012;178:538–542. doi: 10.1667/RR2915.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Box HC, Budzinski EE, Dawidzik JB, Wallace JC, Iijima H. Tandem lesions and other products in X-irradiated DNA oligomers. Radiat Res. 1998;149:433–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Box HC, Budzinski EE, Dawidzik JB, Gobey JS, Freund HG. Free radical-induced tandem base damage in DNA oligomers. Free Rad Biol & Med. 1997;23:1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sato K, Greenberg MM. Selective detection of 2-deoxyribonolactone in DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2806–2807. doi: 10.1021/ja0426185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.San Pedro JMN, Beerman TA, Greenberg MM. DNA damage by C1027 involves hydrogen atom abstraction and addition to nucleobases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4744–4750. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. How easily oxidizable is DNA? One-electron reduction potentials of adenosine and guanosine radicals in aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Douki T, Riviere J, Cadet J. DNA tandem lesions containing 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine and formamido residues arise from intramolecular addition of thymine peroxyl radical to guanine. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:445–454. doi: 10.1021/tx0155909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bergeron F, Auvré F, Radicella JP, Ravanat JL. HO• radicals induce an unexpected high proportion of tandem lesion base lesions refractory to repair by DNA glycosylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5528–5533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000193107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jovanovic SV, Jankovic I, Josimovic L. Electron-transfer reactions of alkyl peroxy radicals. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:9018–9021. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshioka Y, Kitagawa Y, Takano Y, Yamaguchi K, Nakamura T, Saito I. Experimental and theoretical studies on the selectivity of GGG triplets toward one-electron oxidation in B-form DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8712–8719. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sugiyama H, Saito I. Theoretical studies of GG-specific photocleavage of DNA via electron transfer: Significant lowering of ionization potential and 5′-localization of homo of stacked GG bases in B-form DNA. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7063–7068. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Saito I, Nakanura T, Nakatani K, Yoshioka Y, Yamaguchi K, Sugiyama H. Mapping of the hot spots for DNA damage by one-electron oxidation: Efficacy of GG doublets and GGG triplets as a trap in long-range hole migration. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:12686–12687. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miaskiewicz K, Miller J, Ornstein R, Osman R. Molecular dynamics simulations of the effects of ring-saturated thymine lesions on DNA structure. Biopolymers. 1995;35:113–124. doi: 10.1002/bip.360350112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miaskiewicz K, Miller J, Osman R. Energetic basis for structural preferences in 5/6-hydroxy-5,6-dihydropyrimidines: Products of ionizing and ultraviolet radiation action on DNA bases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1218:283–291. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Resendiz MJE, Pottiboyina V, Sevilla MD, Greenberg MM. Direct strand scission in double stranded RNA via a C5-pyrimidine radical. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3917–3924. doi: 10.1021/ja300044e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jacobs AC, Resendiz MJE, Greenberg MM. Product and mechanistic analysis of the reactivity of a C6-pyrimidine radical in RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5152–5159. doi: 10.1021/ja200317w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jacobs AC, Resendiz MJE, Greenberg MM. Direct strand scission from a nucleobase radical in RNA. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:3668–3669. doi: 10.1021/ja100281x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Newman CA, Resendiz MJE, Sczepanski JT, Greenberg MM. Photochemical generation and reactivity of the 5,6-dihydrouridin-6-yl radical. J Org Chem. 2009;74:7007–7012. doi: 10.1021/jo9012805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paul R, Greenberg MM. Rapid RNA strand scission following C2-hydrogen atom abstraction. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:596–599. doi: 10.1021/ja511401g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kuttappan-Nair V, Samson-Thibault F, Wagner JR. Generation of 2′-deoxyadenosine N6-aminyl radicals from the photolysis of phenylhydrazone derivatives. Chem Res Toxicol. 2010;23:48–54. doi: 10.1021/tx900268r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kaloudis P, Paris C, Vrantza D, Encinas S, Perez-Ruiz R, Miranda MA, Gimisis T. Photolabile N-hydroxypyrid-2(1H)-one derivatives of guanine nucleosides: A new method for independent guanine radical generation. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:4965–4972. doi: 10.1039/b909138f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]