Abstract

Background/Aims

The ability of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) to resect large early gastric cancers (EGCs) results in the need to treat large artificial gastric ulcers. This study assessed whether the combination therapy of rebamipide plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) offered benefits over PPI monotherapy.

Methods

In this prospective, randomized, multicenter, open-label, and comparative study, patients who had undergone ESD for EGC or gastric adenoma were randomized into groups receiving either rabeprazole monotherapy (10 mg/day, n=64) or a combination of rabeprazole plus rebamipide (300 mg/day, n=66). The Scar stage (S stage) ratio after treatment was compared, and factors independently associated with ulcer healing were identified by using multivariate analyses.

Results

The S stage rates at 4 and 8 weeks were similar in the two groups, even in the subgroups of patients with large amounts of tissue resected and regardless of CYP2C19 genotype. Independent factors for ulcer healing were circumferential location of the tumor and resected tissue size; the type of treatment did not affect ulcer healing.

Conclusions

Combination therapy with rebamipide and PPI had limited benefits compared with PPI monotherapy in the treatment of post-ESD gastric ulcer (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry, UMIN000007435).

Keywords: Stomach ulcer, Therapeutics, Endoscopy, Antiulcer agents, Proton pump inhibitors

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), an endoscopic resection technique first developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, has become a standard method for the treatment of early gastric cancers (EGC) and some gastric adenomas in Japan, Korea, and other countries.1 ESD has advantages over the prototype endoscopic resection procedure, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), mainly because ESD enables the resection of large lesions en bloc, enhancing complete resection rates.2 However, ESD procedures also have drawbacks, including higher rates of complications, such as delayed bleeding, than EMR.3 In addition, the use of ESD to remove large mucosal EGCs results in larger artificial gastric ulcers, making it necessary to develop therapeutic strategies to heal artificial ulcers after ESD.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the major class of drugs currently used to treat peptic ulcers. PPIs have shown efficacy in treating post-ESD artificial gastric ulcers, with significantly lower rates of delayed bleeding than histamine H2-receptor antagonists.4 However, initial ulcer size has been reported to affect artificial ulcer healing by PPI, as ulcers larger than 4 cm were likely to remain unhealed after 4 weeks of PPI treatment.5 Thus, strategies are needed to treat large artificial ulcers.

The efficacy of PPI therapy also depends on an individual’s ability to metabolize these drugs. PPIs are metabolized by CYP2C19.6,7 However, CYP2C19 genotypes vary, with patients classified into three types: rapid metabolizers (RM), intermediate metabolizers (IM), and poor metabolizers (PM). The PPI rabeprazole, while metabolized mainly nonenzymatically, is partially metabolized by CYP2C19 and shows reduced acid inhibition in individuals with the RM genotype.8,9 However, these data were obtained in healthy volunteers. Thus, the healing effect of rabeprazole in patients with post-ESD artificial gastric ulcer and different CYP2C19 genotypes has not been assessed.

No optimal therapeutic strategy has yet been established for patients with post-ESD gastric ulcers. Although rebamipide add-on therapy to a PPI has been shown more effective than PPI alone in healing artificial ulcers, that study was performed in a small number of patients, and the effects of the CYP2C19 genotype on ulcer healing were not determined.10,11 The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of combination treatment with rebamipide and a PPI in larger numbers of patients with artificial gastric ulcers after ESD. In addition, CYP2C19 polymorphisms were analyzed in patients with EGC or adenoma who underwent ESD, and the effect of CYP2C19 genotype on the efficacy of rebamipide add-on investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study setting

This prospective, randomized, multicenter, and open-labeled comparative study included patients who underwent ESD for EGC or gastric adenoma in the Department of Medicine and Bioregulatory Science of Kyushu University, Aso Iizuka Hospital, Kitakyushu Municipal Hospital, National Hospital Organization Kyushu Medical Center, Saiseikai Fukuoka General Hospital, and Harasanshin Hospital from August 2010 to September 2012. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of each institution. In addition, this trial was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This trial was registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry, number UMIN000007435.

2. Study design

Patients aged ≥20 years who underwent ESD for the treatment of EGC or gastric adenoma, in which the tumor was resected en bloc, were included. Patients were indicated for ESD to treat EGC if they had (1) differentiated mucosal cancer without ulcer findings, irrespective of tumor size; (2) differentiated mucosal cancer ≤30 mm with ulcer findings; (3) differentiated cancer ≤30 mm with minute submucosal invasion (<500 μm from the muscularis mucosa); or (4) undifferentiated mucosal cancer ≤20 mm without ulcer findings.12 Patients were excluded if they (1) were pregnant or possibly pregnant; (2) had a history of allergy to the test drugs; (3) had serious complications; (4) took nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including a cyclooxygenase 2 selective inhibitor or low-dose aspirin; or (5) took corticosteroids.

Patients who underwent piecemeal tumor resection, with resected specimens having affected horizontal or vertical margins, or who underwent gastrectomy as additional therapy after ESD were also excluded. Patients were admitted 1 day before ESD and hospitalized for at least 7 days after ESD. All patients received intravenous omeprazole on the first 2 days after ESD, followed by randomization 1:1 to the PPI rabeprazole (10 mg/day; monotherapy group) or to rabeprazole plus 100 mg rebamipide 3 times/day (combination therapy group) for 54 days. For randomization, the central registration center at Kyushu University assigned a trial drug code to each patient. Patients positive for antibody to Helicobacter pylori underwent eradication therapy after a course of antiulcer treatment with a PPI alone or PPI/rebamipide combination. Thus, the success or failure of H. pylori eradication did not influence the healing rate of post-ESD gastric ulcer.

3. ESD procedure

ESD was performed as described.13–15 Briefly, marks were made on the normal mucosa surrounding the lesion using a needle knife or argon plasma coagulation to indicate safety margins. The submucosal layer was injected with a solution of 10% glycerin, 0.9% NaCl, and 5% fructose (Glyceol; Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) or hyaluronic acid solution (MucoUp; Johnson and Johnson, Tokyo, Japan) to elevate the mucosa. Using an electrosurgical knife, such as an insulation-tipped knife (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), hook knife (Olympus), flex knife (Olympus), flush knife (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan), or clutch cutter (Fuji Film), the normal mucosa surrounding the markings was circumferentially incised and the submucosa beneath the lesion was dissected, with additional injections of Glyceol or MucoUp as required, to remove the entire lesion. Hemostatic forceps (Coagrasper; Olympus) or a clutch cutter was used for hemostasis.

4. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was transfer rate to the ulcer scar, as determined by endoscopy after 4 and 8 weeks, in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups. Secondary endpoints included scarring rates according to the size of the resected tissues and differences in CYP2C19 genotypes of the two groups.

5. Outcome evaluations

Artificial ulcer healing was evaluated endoscopically after 4 and 8 weeks by representative blinded gastroenterologists, with ulcer stage evaluated as described.10 Scar stage (S stage) was defined as healing of the ulcer, whereas healing stage (H stage) indicated that the ulcer had not yet healed. Ulcer size was endoscopically evaluated by inserting a scale thorough a forceps channel. The dissection size was measured by pinning the specimen flat on a rubber plate.

CYP2C19 genotype was assessed in all study subjects by a polymerase chain reaction restriction fragment length polymorphism method with allele-specific primers for identifying the CYP2C19 wild-type (*1) gene and the two mutant alleles, CYP2C19*2 (*2) and CYP2C19*3 (*3). The subjects were classified into three genotype groups: RM (*1/*1), IM (*1/*2 and *1/*3), and PM (*2/*2, *3/*3, and *2/*3).16

6. Sample size estimation

A previous study reported that 68% of patients who received PPI plus rebamipide improved to S stage, compared with 36% in the PPI monotherapy group (p=0.010).10 Based on this finding, and assuming an α-error <0.05 and a β-error <0.2, at least 52 patients per group would be needed to show a between-group difference. Assuming that 10% of patients screened are ineligible and 10% drop out during the study, 65 patients per arm were set as the target sample size.

7. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables in the two groups were compared using Student t-tests, whereas categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test. Factors predictive of ulcer scarring were determined by linear logistic regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of the patients in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups

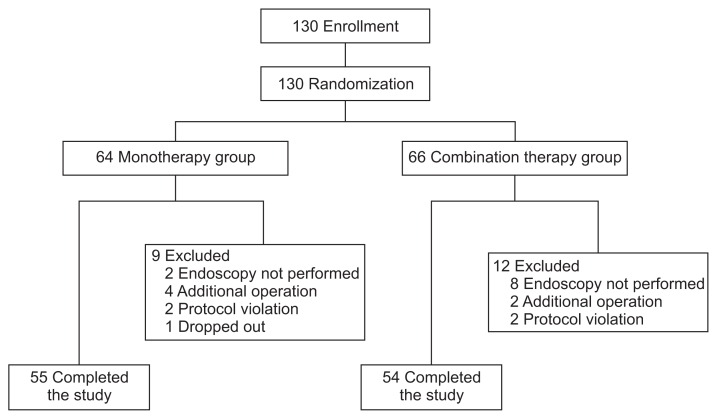

A total of 130 patients were deemed eligible and randomized to the two study groups (Fig. 1). Nine patients in the mono-therapy group and 12 in the combination therapy group were excluded from the study owing to the performance of additional gastrectomy, protocol violation, lack of endoscopy, or drop out, leaving 55 patients in the monotherapy group and 54 in the combination therapy group. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 130 enrolled patients. There were no significant differences in age, sex, drinking habits, smoking habits, presence or absence of H. pylori infection, history of treatment for gastric cancer, tumor locations, macroscopic and histological tumor types, severity of atrophic gastritis, association of ulcer findings with the tumor, size of resected tissue, and size of the post-ESD ulcer or tumor depth between two groups. CYP2C19 genotype was also similar in the two groups.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study participants.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Features of Patients and Lesions

| Clinicopathological feature | Monotherapy group (n=64) | Combination therapy group (n=66) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 70.3±8.6 | 68.7±8.5 | 0.289 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 41 | 43 | 1 |

| Female | 23 | 23 | |

| Drinking habit | |||

| Absent | 30 | 32 | 0.863 |

| Present | 34 | 34 | |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Absent | 44 | 42 | 0.581 |

| Present | 20 | 24 | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | |||

| Negative | 23 | 20 | 0.577 |

| Positive | 41 | 46 | |

| History of gastric cancer | |||

| Absent | 57 | 61 | 0.558 |

| Present | 7 | 5 | |

| Location | |||

| Upper | 5 | 7 | 0.396 |

| Middle | 27 | 34 | |

| Lower | 32 | 25 | |

| Circumference | |||

| Lesser curvature | 32 | 23 | 0.273 |

| Greater curvature | 11 | 11 | |

| Anterior wall | 11 | 15 | |

| Posterior wall | 10 | 17 | |

| Atrophic gastritis | |||

| Closed | 8 | 12 | 0.471 |

| Open | 54 | 54 | |

| Macroscopic type | |||

| 0–I | 7 | 4 | 0.357 |

| 0–IIa | 25 | 25 | |

| 0–IIb | 2 | 0 | |

| 0–IIc | 30 | 37 | |

| Histological type | |||

| Differentiated cancer | 44 | 50 | 0.236 |

| Undifferentiated cancer | 3 | 0 | |

| Adenoma | 17 | 16 | |

| Size of resected tissue, mm | 38.8±14.2 | 40.7±13.8 | 0.432 |

| Size of post-ESD ulcer, mm | 42.8±15.7 | 44.5±13.5 | 0.508 |

| Depth of the tumor | |||

| M (mucosal cancer and adenoma) | 58 | 62 | 0.092 |

| SM1 | 2 | 4 | |

| SM2 or deeper | 4 | 0 | |

| Association of ulcerative findings | |||

| Absent | 60 | 62 | 1 |

| Present | 4 | 4 | |

| Genotype of CYP2C19 | |||

| RM | 20 | 26 | 0.346 |

| IM | 30 | 23 | |

| PM | 8 | 11 | |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number.

Genotype of CYP2C19 was examined for 58 patients in the monotherapy group and 60 patients in the combination therapy group, who agreed to take such genetic tests.

ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; M, mucosa; SM, submucosa; RM, rapid metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer.

2. Outcomes of monotherapy and combination therapy for post-ESD gastric ulcers

The transfer rates of post-ESD artificial gastric ulcers to S stage in the monotherapy and combination groups were 19.3% and 9.5%, respectively, at 4 weeks and 84.5% and 81.8%, respectively, at 8 weeks in intention-to-treat analysis (ITT), without significant difference. In per-protocol (PP) analysis, the transfer rates to S stage at 4 weeks (17.3% vs 11.5%, p>0.05) and 8 weeks (85.5% vs 83.3%, p>0.05) were also similar in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups (Table 2). There was no significant add-on effect of rebamipide in the entire population.

Table 2.

Stages of Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Gastric Ulcer after 4 and 8 Weeks of Treatment

| Monotherapy group | Combination therapy group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat analysis | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 46 | 57 | 0.189 |

| S stage | 11 | 6 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 9 | 10 | 0.803 |

| S stage | 49 | 45 | |

| Per-protocol analysis | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 43 | 46 | 0.578 |

| S stage | 9 | 6 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 8 | 9 | 0.797 |

| S stage | 47 | 45 | |

H stage, healing stage; S stage, scar stage.

As PPI monotherapy may not be sufficient to heal large post-ESD gastric ulcers and rebamipide may have some additive effect, patients were divided by the size of the resected tissue. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis showed that the cutoff of resected tissue size for distinguishing transfer to S stage at 8 weeks was 42.78 mm in ITT analysis and 42.1 mm in PP analysis. However, the rates of S stage at 4 and 8 weeks in patients with large and small resected tissue size did not differ significantly in the two groups, in either ITT or PP analysis (Table 3). Thus, rebamipide add-on did not have a substantial effect in patients with large post-ESD ulcers.

Table 3.

Stages of Large and Small Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Gastric Ulcers after 4 and 8 Weeks of Treatment

| Monotherapy group | Combination therapy group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat analysis | |||

| Resected tissue, ≤42.8 mm | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 36 | 38 | 0.549 |

| S stage | 8 | 5 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 3 | 5 | 0.483 |

| S stage | 40 | 37 | |

| Resected tissue, >42.8 mm | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 10 | 19 | 0.276 |

| S stage | 3 | 1 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| S stage | 9 | 8 | |

| Per-protocol analysis | |||

| Resected tissue, ≤42.1 mm | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 34 | 35 | 0.756 |

| S stage | 7 | 5 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 3 | 5 | 0.713 |

| S stage | 39 | 37 | |

| Resected tissue, >42.1 mm | |||

| 4 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 9 | 11 | 0.591 |

| S stage | 2 | 1 | |

| 8 Weeks | |||

| H stage | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| S stage | 8 | 8 | |

H stage, healing stage; S stage, scar stage.

Another possibility is that the healing of post-ESD ulcer may be delayed in patients with the CYP2C19 RM or IM genotype treated with PPI monotherapy and that rebamipide may have some additive effect on PPI. In analyzing the CYP2C19 genotype, the transfer rates to S stage at 8 weeks in patients with RM, IM, and PM were 80.0%, 80.8%, and 100%, respectively, in the monotherapy group, and 81.0%, 81.8%, and 88.9% in the combination therapy group, in ITT analysis. In PP analysis, transfer rates to S stage at 8 weeks were 80.0%, 82.6%, and 100%, respectively, in the monotherapy group, and 81.0%, 85.7% and 88.9%, respectively, in the combination therapy group. None of the between-group differences was statistically significant in either ITT or PP analysis (Table 4). Similarly, transfer rates to S stage at 4 weeks for each genotype were similar in the two groups in both analysis sets.

Table 4.

Stages of Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Gastric Ulcer at 4 and 8 Weeks of Treatment in the CYP2C19 Genotype Subgroup

| Monotherapy group | Combination therapy group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat analysis | ||||

| 4 Weeks | ||||

| RM | H stage | 13 | 24 | 0.067 |

| S stage | 5 | 1 | ||

| IM | H stage | 23 | 18 | 0.715 |

| S stage | 4 | 5 | ||

| PM | H stage | 6 | 10 | 0.183 |

| S stage | 2 | 0 | ||

| 8 Weeks | ||||

| RM | H stage | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| S stage | 16 | 17 | ||

| IM | H stage | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| S stage | 21 | 18 | ||

| PM | H stage | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| S stage | 8 | 8 | ||

| Per-protocol analysis | ||||

| 4 Weeks | ||||

| RM | H stage | 13 | 19 | 0.083 |

| S stage | 5 | 1 | ||

| IM | H stage | 21 | 16 | 0.232 |

| S stage | 2 | 5 | ||

| PM | H stage | 6 | 9 | 0.206 |

| S stage | 2 | 0 | ||

| 8 Weeks | ||||

| RM | H stage | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| S stage | 16 | 17 | ||

| IM | H stage | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| S stage | 19 | 18 | ||

| PM | H stage | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| S stage | 8 | 8 | ||

RM, rapid metabolizer; H stage, healing stage; S stage, scar stage; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer.

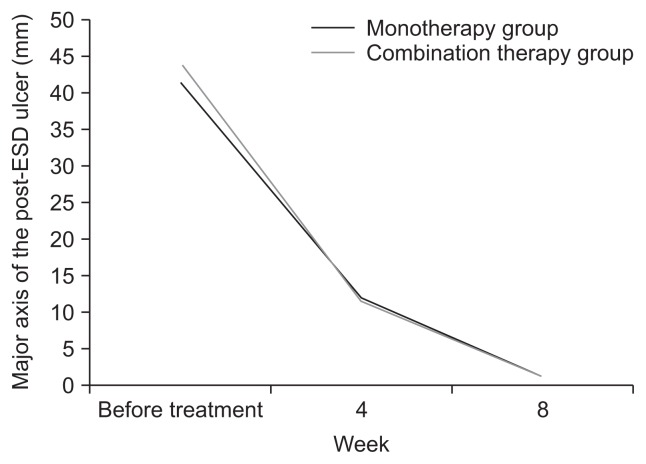

Fig. 2 shows the mean sizes of post-ESD ulcers before treatment and 4 and 8 weeks after treatment. The rate of reduction in ulcer size was similar in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups.

Fig. 2.

Rates of reduction of post-endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) gastric ulcer size in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups. Repeated measurement analysis interaction: p=0.386.

Delayed bleeding was observed in one patient in the mono-therapy group 22 days after ESD and in one patient in the combination therapy group 14 days after ESD: there was no significant difference.

3. Factors influencing the healing of post-ESD ulcer

As the scarring ratios were similar in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups, factors influencing the healing of post-ESD ulcer at 8 weeks were analyzed. Univariate analysis showed that smoking habit, histological type, size of the resected tissue, and size of the post-ESD artificial ulcer were significant factors affecting scarring (Table 5). Post-ESD ulcer size was excluded from the subsequent multivariate analysis, owing to the strong correlation between resected tissue size and ulcer size (r=0.81). Thus, circumferential location of the tumor and size of the resected tissue were independent factors for scarring (Table 6). Treatment type, whether monotherapy or combination therapy, was not associated with the healing of post-ESD ulcers.

Table 5.

Univariate Analyses of Factors Influencing the Healing of Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Ulcer at 8 Weeks

| H stage | S stage | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 72.0±8.3 | 68.8±8.7 | 0.154 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 11 | 65 | 0.423 |

| Female | 8 | 29 | |

| Drinking habit | |||

| Absent | 12 | 42 | 0.208 |

| Present | 7 | 52 | |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Absent | 17 | 57 | 0.017 |

| Present | 2 | 37 | |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | |||

| Negative | 5 | 37 | 0.313 |

| Positive | 14 | 57 | |

| History of gastric cancer | |||

| Absent | 18 | 84 | 0.687 |

| Present | 1 | 10 | |

| Location | |||

| Upper | 1 | 8 | 0.233 |

| Middle | 6 | 47 | |

| Lower | 12 | 39 | |

| Circumference | |||

| Lesser curvature | 4 | 42 | 0.147 |

| Greater curvature | 3 | 17 | |

| Anterior wall | 5 | 18 | |

| Posterior wall | 7 | 17 | |

| Atrophic gastritis | |||

| Closed | 2 | 15 | 0.732 |

| Open | 17 | 77 | |

| Macroscopic type | |||

| 0–I | 0 | 11 | 0.495 |

| 0–IIa | 8 | 32 | |

| 0–IIb | 0 | 2 | |

| 0–IIc | 11 | 49 | |

| Histological type | |||

| Differentiated cancer | 18 | 63 | 0.005 |

| Undifferentiated cancer | 1 | 2 | |

| Adenoma | 0 | 29 | |

| Size of resected tissue, mm | 50.2±15.4 | 36.5±12.9 | 0.001 |

| Size of post-ESD ulcer, mm | 52.4±17.0 | 41.3±14.1 | 0.003 |

| Depth of the tumor | |||

| M (mucosal cancer and adenoma) | 18 | 89 | 0.397 |

| SM1 | 0 | 4 | |

| SM2 or deeper | 1 | 1 | |

| Association of ulcerative findings | |||

| Absent | 17 | 89 | 0.334 |

| Present | 2 | 5 | |

| Genotype of CYP2C19 | |||

| RM | 8 | 33 | 0.446 |

| IM | 9 | 39 | |

| PM | 1 | 16 | |

| Treatment | |||

| Monotherapy | 9 | 49 | 0.803 |

| Combination therapy | 10 | 45 | |

Data are presented as mean±SD or number.

H stage, healing stage; S stage, scar stage; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; M, mucosa; SM, submucosa; RM, rapid metabolizer; IM, intermediate metabolizer; PM, poor metabolizer.

Table 6.

Multivariate Analyses of Predictive Factors for Nonhealing of Post-Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Gastric Ulcer at 8 Weeks

| β | SE | R | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size of the resected tissue (larger) | 0.0495 | 0.021 | 0.18 | 0.0213 | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

| Smoking habit (no vs yes) | 1.3142 | 0.838 | 0.07 | 0.1171 | 3.73 (0.72–19.29) |

| Location (L vs M vs U) | 0.9833 | 0.561 | 0.11 | 0.0797 | 2.67 (0.89–8.03) |

| Circumference (PW vs AW vs GC vs LC) | 0.5188 | 0.259 | 0.14 | 0.0455 | 1.66 (1.00–2.79) |

| Histological type (DC vs UC vs adenoma) | 1.4649 | 0.796 | 0.12 | 0.0658 | 4.33 (0.91–20.59) |

SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; L, lower; M, middle; U, upper; PW, posterior wall; AW, anterior wall; GC, greater curvature; LC, lesser curvature; DC, differentiated cancer; UC, undifferentiated cancer.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies reported that rebamipide had an additive effect on the treatment of post-ESD gastric ulcer when included with a PPI.10,11 However, this study found no difference in the transfer rate to S stage between patients treated with rabeprazole alone and patients treated with a combination of rabeprazole and rebamipide. Compared with rabeprazole 20 mg/day alone, the addition of rebamipide 300 mg/day to rabeprazole 20 mg/day was reported to significantly improve transfer rates to S stage at 8 weeks, from 54.8% to 86.7%.11 That study employed a similar study design as ours, except that the dosage of rabeprazole (20 mg/day) was higher than ours (10 mg/day). Despite the higher dosage of rabeprazole, the scarring rate in the monotherapy group was higher in our study (85.5%) than in the earlier trial (54.8%). Although the earlier study showed that the between-group differences in healing rates were not significant for ulcers located in the upper and middle thirds of the stomach, the rates for ulcers located in the lower third of the stomach were much lower in the monotherapy than in the combination therapy group (41.7% vs 91.7%). In our study, however, we did not observe any between-group difference in healing rates of ulcers located in the lower third of the stomach (data not shown). The previous study also reported that the between-group difference in ulcer healing rates differed in patients with O-3 type atrophic gastritis, a difference not observed in our study (data not shown).

The addition of rebamipide 300 mg/day to rabeprazole 10 mg/day was reported to significantly improve the scarring ratio of post-ESD gastric ulcer after 4 weeks, from 36% to 68%.10 Although that study failed to show a significant between-group difference in healing rates for ulcers >40 mm, a later study showed that the addition of rebamipide increased healing rates for ulcers >40 mm.17 In the present study, scarring rates at 4 weeks were 17.3% and 11.5% in the monotherapy and combination therapy groups, respectively, with no additive effect of rebamipide observed. The reasons for these discrepancies remain unclear.

The above mentioned studies had relatively small sample sizes (n=62 and n=64, respectively).10,11 To analyze the add-on effect of rebamipide in larger numbers of patients, we enrolled 130 patients, but found that rebamipide did not have a substantial add-on effect. However, another study with a similar design in an even larger number of patients (n=309) found that rebamipide had an additive effect when administered along with a PPI.18 Thus, one limitation of the current study may have been insufficient statistical power. However, the other study tested a different type of PPI (pantoprazole), preventing a simple comparison of the results of the two studies.

Another limitation of the study is that we analyzed only serum H. pylori antibody as the test for H. pylori infection. As the presence of H. pylori antibody does not always means the current infection of H. pylori, it might be ideal to employ two different types of diagnostic modalities such as H. pylori antibody and rapid urease test. However, only H. pylori antibody was employed due to the feasibility reason. Thus, it is considered some of the patients with prior infection were included in the H. pylori positive group.

PPI monotherapy for 4 weeks was reported to be insufficient for healing large post-ESD ulcers,5 suggesting that rebamipide add-on to PPI may be more effective in patients with large post-ESD ulcers. However, no such additive effect was observed, even in patients with large resected tissue. Moreover, CYP2C19 genotype was thought to affect the healing of post-ESD ulcer by PPIs. It was predicted that a PPI alone may be sufficient for the treatment of post-ESD ulcers in patients classified as PM, whereas the addition of rebamipide may be necessary in patients classified as RM and IM. However, no differences in these subgroups were observed between patients treated with monotherapy and combination therapy.

Compared with H2 receptor antagonists, PPIs were reported to significantly reduce the incidence of delayed bleeding after ESD.4 In this study, only one patient in each group experienced delayed bleeding; however, the sample size was too small to detect any differences. As the incidence of delayed bleeding in patients receiving PPI monotherapy is estimated to be small, a very large sample size will be necessary to determine the effects of additional rebamipide on delayed bleeding rates.

Multivariate analyses of factors that influence the healing of post-ESD-ulcer showed that circumferential location of the tumor and the size of the resected tissue were independent factors affecting ulcer healing. Tumor location in the lesser curvature seemed to be predictive of scarring, but this factor was not assessed in previous reports.10,11 Type of treatment, whether mono-therapy or combination therapy, was not predictive of ulcer healing, providing further evidence that rebamipide had little additive effect on PPIs.

In conclusion, rebamipide add-on therapy to PPI did not show substantial benefits, when compared with PPI monotherapy, in the treatment of post-ESD ulcers. Another approach may therefore be necessary to improve the treatment of post-ESD ulcers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mr. Noriya Taki for performing the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Kazuhiko Nakamura received research grants from Eisai Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Johnson and Johnson. Eikichi Ihara received research grants from Eisai Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gotoda T. Endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, et al. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262–270. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0389-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929–942. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1954-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Yamada T, et al. Effect of a proton pump inhibitor or an H2-receptor antagonist on prevention of bleeding from ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1610–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh TH, Jung HY, Choi KD, et al. Degree of healing and healing-associated factors of endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcers after pantoprazole therapy for 4 weeks. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1494–1499. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0506-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson T, Miners JO, Veronese ME, Birkett DJ. Identification of human liver cytochrome P450 isoforms mediating secondary omeprazole metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;37:597–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katsuki H, Nakamura C, Arimori K, Fujiyama S, Nakano M. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19 and lansoprazole pharmacokinetics in Japanese subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:391–396. doi: 10.1007/s002280050307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horai Y, Kimura M, Furuie H, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects and kinetic disposition of rabeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotypes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:793–803. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirai N, Furuta T, Moriyama Y, et al. Effects of CYP2C19 genotypic differences in the metabolism of omeprazole and rabeprazole on intragastric pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1929–1937. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato T, Araki H, Onogi F, et al. Clinical trial: rebamipide promotes gastric ulcer healing by proton pump inhibitor after endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled study. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:285–290. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara S, Morita Y, Toyonaga T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of rebamipide plus rabeprazole for the healing of artificial ulcers after endoscopic submucosal dissection. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0372-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3) Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura K, Honda K, Akahoshi K, et al. Suitability of the expanded indication criteria for the treatment of early gastric cancer by endoscopic submucosal dissection: Japanese multicenter large-scale retrospective analysis of short- and long-term outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:413–422. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.940377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akahoshi K, Honda K, Motomura Y, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection using a grasping-type scissors forceps for early gastric cancers and adenomas. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:24–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itaba S, Iboshi Y, Nakamura K, et al. Low-frequency of bacteremia after endoscopic submucosal dissection of the stomach. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubota T, Chiba K, Ishizaki T. Genotyping of S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation in an extended Japanese population. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:661–666. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki H, Kato T, Onogi F, et al. Combination of proton pump inhibitor and rebamipide, a free radical scavenger, promotes artificial ulcer healing after endoscopic submucosal dissection with dissection size >40 mm. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;51:185–188. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.12-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shin WG, Kim SJ, Choi MH, et al. Can rebamipide and proton pump inhibitor combination therapy promote the healing of endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcers? A randomized, prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:739–747. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]