Abstract

Since its introduction as an alternative intestinal microbiota alteration approach, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been increasingly used as a treatment of choice for patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), but no reports exist regarding FMT via percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy (PEC). This report describes the case of a 24-year-old man with a 7-year history of recurrent, steroid-dependent UC. He received FMT via PEC once per day for 1 month in the hospital. After the remission of gastrointestinal symptoms, he was discharged from the hospital and continued FMT via PEC twice per week for 3 months at home. The frequency of stools decreased, and the characteristics of stools improved soon thereafter. Enteral nutrition was regained after 1 week, and an oral diet was begun 1 month later. Two months after the FMT end point, the patient resumed a normal diet, with formed soft stools once per day. The follow-up colonoscopy showed normal mucus membranes; then, the PEC set was removed. On the subsequent 12 months follow-up, the patient resumed orthobiosis without any gastrointestinal discomfort and returned to work. This case emphasizes that FMT via PEC can not only induce remission but also shorten the duration of hospitalization and reduce the medical costs; therefore, this approach should be considered an alternative option for patients with UC.

Keywords: Fecal microbiota transplantation, Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy, Colitis, ulcerative

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that affects the colorectum. UC is most commonly diagnosed in young adulthood patients although it can affect patients of any age and either sex.1 The course of UC is generally relapsing-remitting, with patients experiencing few or no gastrointestinal symptoms in between symptomatic relapses.2 The precise etiology of UC is unclear, however, over-stimulation of an inadequate mucosal immune response towards components of the commensal microbiota appears to be a major pathophysiological pathway.3 The therapy of UC is rapidly evolving, and both conventional and novel drug treatments have been proven efficacy, including 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), steroids, immunosuppressants and biological therapies.4,5 However, some patients become refractory to standard treatments and have a poor quality of life with many requiring surgery.6 Given the role of the gastrointestinal microbiota in driving inflammation in UC, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been investigated to alter the colonic microbiota and induce beneficial changes in colonic mucosa.7 However, limited reports of FMT in UC were delivered by means of colonoscopy and/or enemas,7–9 there was no report via percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy (PEC). Herein, we report the successful clinical application of FMT via PEC in a recurrent steroid-dependent UC patient who had suffered from gastrointestinal symptoms for 7 years.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old male patient with 7-year history of recurrent UC was admitted to Jinling Hospital. On July 23, 2007, he suffered from intermittent abdominal pain and mucopurulent bloody stools 4 to 6 times per day without fever. E3 type UC (pancolitis) according to Montreal classification had been confirmed after colonoscopy.10 A Mayo score of 9 was assessed.11 Before admission, he received standard drug therapies according to the UC guidelines of American College of Gastroenterology.12 Concomitant treatments such as 5-ASA, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressive therapy (e.g., azathioprine), and anti-tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNF-α) medications had been used at a stable dose for at least 12 weeks (4 weeks for glucocorticoids), but his symptoms couldn’t be relieved without glucocorticoids. Considering to facilitate the withdrawal of conventional therapies, we decided to attempt FMT via PEC once a day to alter the colonic microbiota and relieve his symptoms. The protocol was designed according to the ethical principles outlined by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the local ethics committee of Jinling Hospital. The participant had provided written informed consent.

Under basal anesthesia with Diprivan (AstraZeneca S.p.A, Basiglio, Italy), colonoscopy was performed and showed diffuse mucous hyperemia, erosion and ulcer formation in total colon and rectum (Fig. 1). The PEC procedure was similar to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) pull technique initially described by Ponsky et al.13 A colonoscope was inserted to the cecum and a transillumination light point was noted in the right lower quadrant of the abdominal wall. The correct position for PEC placement was verified by cecal indentation with direct digital pressure on the abdomen and by transillumination. The abdominal wall was then prepared, draped, and anesthetized in a sterile fashion. A 19-gauge Seldinger cannula was inserted through the abdominal wall into the cecum (Fig. 2A). A 300-cm-long wire was passed through the needle and tightened with the snare. Then colonoscope was then withdrawn from the colon along with the snare and the insertion wire. The catheter system (Freka PEG Set Gastric FR 15; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) was tied to the wire and was slowly pulled retrograde through the colon, exiting the abdominal wall, and was fixed in place with external bolsters. Finally, a colonoscope was repeated to check the final placement after the cecostomy tube was fixed (Fig. 2B).

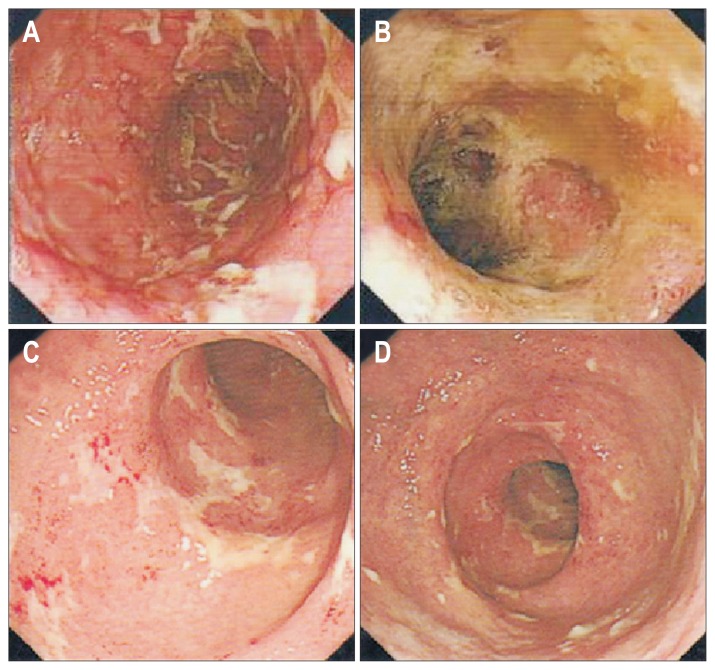

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopic examination showed diffuse mucus hyperemia, erosion and ulcer formation in the total colon and rectum. (A) Transverse colon; (B, C) sigmoid colon; (D) rectum.

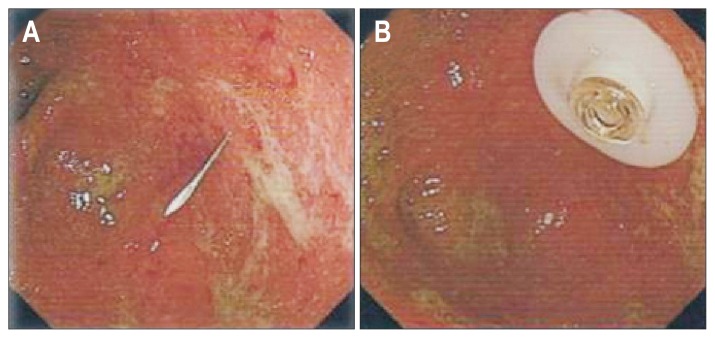

Fig. 2.

Endoscopic view of the cecum during percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy. (A) A 19-gauge Seldinger cannula was inserted into the cecum; (B) the gasket of the cecostomy tube.

FMT was prepared from stool donated by his father who was 51-year-old and was healthy as assessed by a screening questionnaire. He did not smoke or take drugs with negative screening investigations for hepatitis A, B and C virus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human immunodeficiency virus, and negative stool tests for Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia coli, Campylobacter, Yersinia, ova, parasites, and Clostridium difficile. He had not suffered diarrhea, blood in stool or antibiotic use within 1 month before FMT. He had no history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), or gastrointestinal malignancy. Other examinations include electrocardiogram, abdominal computed tomography, urine routine, blood routine, blood biochemistry and blood coagulate function were normal. Before FMT, the donor took regular diet without alcohol and spicy foods, and he did not take any antibiotics. Donor stool was handled as a level 2 biohazard with appropriate universal precautions. About 100 g of donor stool was mixed with 250 mL sterile warm normal saline by an electric blender in a sterilized glass beaker for 5 minutes. Filter paper was then placed over the mixture to remove larger sediments, and nearly 250 mL filtered stool suspension was gathered. The stool suspension was poured into an aseptic glass bottle and administered with the patient in the supine position into colon via PEC tube for more than 1 hour each time.

Before FMT, patient characteristics and baseline condition were assessed thoroughly. Clinical disease activity was followed by the Mayo scoring system, and with a Mayo score of 9.11 All conventional medications for UC except mesalazine were stopped prior to the first FMT, and mesalazine 3.0 g daily was given during FMT. The patient was monitored for 30 minutes after FMT for any immediate adverse events. On the first day, he complained about a watery stool with little blood 90 minutes after FMT, and the peripheral blood leukocyte count rose up to 12.3×109/L on day 2 but returned to normal on day 5. Blood C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were all in normal ranges during the period. The patient resumed enteral nutrition (EN) 3 days later. He was concomitantly recovered total EN without total parenteral nutrition 7 days later. He formed a nearly regular bowel habit with symptom-free and resumed oral liquid diet 1 month after treatment. One month after FMT, a colonoscope was repeated and showed only scattered small ulcers in the rectum with smooth mucous membrane in the colon (Fig. 3A and B). The clinical disease activity was assessed using the Mayo scoring system with a Mayo score of 4.11 He was discharged home and performed FMT twice a week for 3 months at home. Three months later, the patient has resumed to normal diet with formed soft stool once a day. On examination, the colonoscopy showed no lesions in the colon and rectum (Fig. 4A and B). The Mayo score was assessed as 0.11 We decided to remove the PEC set. After FMT, mesalazine 2.0 g daily was given as a sustain treatment for one month, no other medication was used. In the following 12 months, we learnt nothing was abnormal through telephone follow-up survey. He resumed normal life with symptom-free and got his job back.

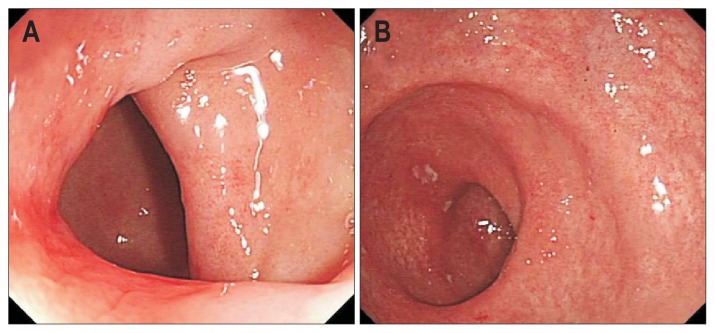

Fig. 3.

Colonoscopic examination showed scattered small ulcers in the rectum with smooth mucus membranes in the colon. (A) Sigmoid colon; (B) rectum.

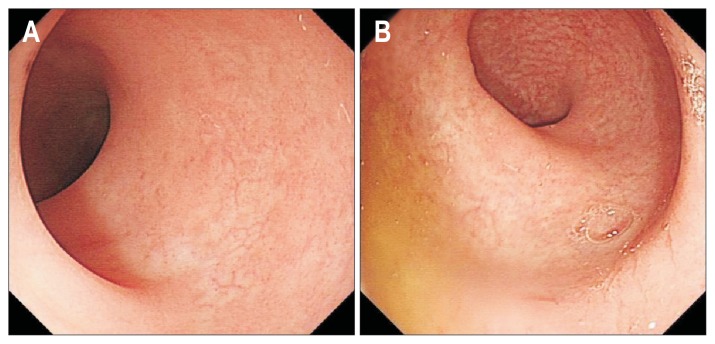

Fig. 4.

Colonoscopy examination showed no lesions in the colon and rectum. (A) Colon; (B) rectum.

DISCUSSION

UC, an inflammatory disorder affects the colorectum, is a chronic relapsing IBD characterised by superficial mucosal inflammation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and rectal bleeding.14,15 The precise etiology of UC is unclear but it is thought to arise from an inadequate immune response to commensal microbiota.7 Current medical treatments remain imperfect and including 5-ASA, steroids, immunosuppressants and biological therapies.4 However, some patients become refractory to conventional treatments and some have significant side effects. Given the role of the gastrointestinal microbiota in driving inflammation in UC, therapies that alter the microbiota have been investigated.6

FMT, which is the transfer of fecal suspension from a healthy donor into the gastrointestinal tract of another person, has emerged as a novel approach for specific diseases.16 Although, it is first known as a treatment of pseudomembranous colitis caused by Micrococcus pyogenes (Staphylococcus) in 1958,17 FMT has been ignored for about 25 years. Until 1983, Schwan et al. reported their first use of FMT by enema for C. difficile infection (CDI).18 The success of FMT in treating CDI has raised the possibility that FMT may be beneficial in IBD, IBS, and other disorders.16 Excitement around the possibility of FMT for UC has grown rapidly, Borody et al.19 first reported their successful use of FMT for UC patient in 1989. Subsequently, there have been some reports describing the use of FMT for UC patients. A systematic review of case reports in 2014 by Sha et al.20 counted 94 UC patients had been treated by FMT and approximately 90% showed clinical response after FMT.3 In 2015, Kellermayer et al.,8 Rossen et al.,21 and Moayyedi et al.7 also published their successful experiences in treating UC patients by FMT. Until 1989, retention enema was the most common approach for FMT. However, alternative methods have been used subsequently, including fecal infusion via nasogastric tube,22 colonoscopy,23 and retention enemas.24 To date, more than 800 cases of FMT have been reported worldwide including approximately 25% by nasogastric tube and 75% by colonoscopy or retention enema.16,20

Although FMT has gained increasing recognition as a potential treatment for UC, its optimal route of administration remains uncertain. Administration of stool suspension via the nasogastric tube is convenient, inexpensive, and technically simple. However, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth is a theoretical risk in those patients. The colonoscopic approach is favored over retention enema for UC whereas enemas only reach the splenic flexure. Administration via colonoscopy, the entire colon can be infused with stool suspension, and the extent and severity of UC can also be elucidated at the same time therapy is being given.16 However, colonoscopy must be performed in hospital and most patients can’t tolerate frequent colonoscope. What’s more, in patients with significant colonic distention and severe colitis, colonoscopy may be technically challenging and potentially dangerous. In such patients, colonoscope may scrape off scabs of deep ulcers, which may result in severe complications such as enterobrosis and massive haemorrhage.25

An effective, comfortable and acceptant technique of FMT for UC patients is needed. PEC, first described in 1986 by Ponsky et al.,13 was mainly used to the management of recurrent pseudoobstruction and chronic intractable constipation.26 Up to now, most of the FMT were conducted through conventional approaches, there was no report of FMT via PEC in patients with UC. Herein, we first reported our successful attempt to use FMT through PEC in a recurrent steroid-dependent UC patient. Before admission, our patient received standard drug therapies according to the UC guidelines, but his symptoms cannot be relieved without glucocorticoids. Considering to facilitate the withdrawal of conventional therapies, we attempted in-hospital and home FMT via PEC. Our patient tolerated the procedure well and withdrew immunotherapy with symptom-free for at least 1 year following FMT. The preliminary result was satisfactory and our patient experienced subjective and clinical improvement, which showed the safety and feasibility of FMT via PEC.

Several advantages of FMT via PEC for treating UC merit discussion in this case. First, FMT was almost always applied to UC patient through colonoscopy or retention enemas and there was no report about the FMT via PEC, while this case was a recurrent steroid-dependent UC patient, and finally gained the successful treatment. Second, it is a simple, inexpensive, and acceptable endoscopic procedure, the stool suspension passes anterogradely through the colon and rectum which conforms to human’s physiology and is beneficial to flora reconstruction. Third, the FMT procedure is easy to learn and can be repeated easily at home when necessary. Furthermore, the PEC set can be removed easily without further intervention if the treatment is completed or unsuccessful. Although FMT via PEC has a wide range of advantages, several points must be emphasized to avoid intraprocedural or postprocedural complications: placing the PEC device in the appropriate position to avoid hematoma during surgery; keeping the skin clean and dry to prevent infection around the PEC; adjusting the external bolsters of PEC to a suitable tension every 48 hours in early postoperative period to decrease the risk of pressure necrosis.

In our experience, FMT via PEC is a convenient, safe, and effective option in the management of UC. FMT via PEC may induce beneficial changes in gastrointestinal microbiota and colonic mucosa of UC patient. However, further randomized trials will be required in the future to answer many challenging questions with respect to the clinical indications, therapeutic possibilities, and potential complications.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kane SV. Systematic review: adherence issues in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:577–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinsley A, Naymagon S, Mathers B, Kingsley M, Sands BE, Ullman TA. Early readmission in patients hospitalized for ulcerative colitis: incidence and risk factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1103–1109. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1020862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson JL, Edney RJ, Whelan K. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talley NJ, Abreu MT, Achkar JP, et al. An evidence-based systematic review on medical therapies for inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106( Suppl 1):S2–S25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park SC, Jeen YT. Current and emerging biologics for ulcerative colitis. Gut Liver. 2015;9:18–27. doi: 10.5009/gnl14226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Hanauer SB. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 2013;346:f432. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:102–109. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.001. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellermayer R, Nagy-Szakal D, Harris RA, et al. Serial fecal microbiota transplantation alters mucosal gene expression in pediatric ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:604–606. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grinspan AM, Kelly CR. Fecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis: not just yet. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:15–18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1371–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ponsky JL, Aszodi A, Perse D. Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy: a new approach to nonobstructive colonic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:108–111. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(86)71770-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conrad K, Roggenbuck D, Laass MW. Diagnosis and classification of ulcerative colitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:463–466. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eun CS, Han DS. Does the cyclosporine still have a potential role in the treatment of acute severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis? Gut Liver. 2015;9:567–568. doi: 10.5009/gnl15293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandt LJ, Aroniadis OC. An overview of fecal microbiota transplantation: techniques, indications, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:240–249. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.03.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery. 1958;44:854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwan A, Sjölin S, Trottestam U, Aronsson B. Relapsing clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of homologous faeces. Lancet. 1983;2:845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)90753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borody TJ, George L, Andrews P, et al. Bowel-flora alteration: a potential cure for inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome? Med J Aust. 1989;150:604. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sha S, Liang J, Chen M, et al. Systematic review: faecal microbiota transplantation therapy for digestive and nondigestive disorders in adults and children. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1003–1032. doi: 10.1111/apt.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:110–118. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.045. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aas J, Gessert CE, Bakken JS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: case series involving 18 patients treated with donor stool administered via a nasogastric tube. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:580–585. doi: 10.1086/367657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Persky SE, Brandt LJ. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea by administration of donated stool directly through a colonoscope. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3283–3285. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverman MS, Davis I, Pillai DR. Success of self-administered home fecal ransplantation for chronic Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Gastroenterol epatol. 2010;8:471–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guo B, Harstall C, Louie T, Veldhuyzen van Zanten S, Dieleman LA. Systematic review: faecal transplantation for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:865–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynch CR, Jones RG, Hilden K, Wills JC, Fang JC. Percutaneous endoscopic cecostomy in adults: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]