Abstract

The results of studies on the structure and reactivity of spiro[5.2]oct-5,7-diene-4yl carbocation [phenonium ion] have had a significant impact on the course of discussion about the distinction between classical and nonclassical carbocations. This minireview will present a brief overview of the structure, bonding and reactivity of ring substituted phenonium ions (X-4+), with an emphasis on work completed since 2004. The discussion will focus on the development of new experimental protocol for determination of the selectivity for addition of nucleophilic anions to X-4+ in aqueous solution. The existing relationships between carbocation lifetime and nucleophilic selectivity, and the known lifetime of ca 140 sec for spiro[2.5]oct-4,7-diene-6-one provide rough estimates of the lifetimes for 4-Me-X-4+ and 4-MeO-X-4+ in aqueous solution. Evidence is presented that nucleophile addition to X-4+ proceeds through an “exploded” transition state, with relatively weak bonding the nucleophile and leaving group, and the development of significant positive charge at the reacting primary cyclopropyl carbon.

TOC image

Ring-substituted phenonium ions are highlighted as early examples of bridging intermediates of solvolysis reactions at aliphatic carbon. Results from recent studies on the lifetime and the mechanism for nucleophilic substitution at these cations are reviewed.

Many interesting wrinkles in the fabric of organic chemistry have been encountered in the study of carbon skeletal rearrangement reactions that proceed through reactive carbocation intermediates.[1–4] The observation of these rearrangements, such as that featured in this minireview (Scheme 1), provided early evidence for the formation of novel reactive intermediates with unexpected bridging bonds at carbon. The structures of these intermediates were then characterized in exquisite detail through enormous batteries of experimental and theoretical studies.[5, 6] This minireview will present a brief overview of the structure, bonding and reactivity of phenonium ions, with an emphasis on work completed since the most recent 2004 review of these ions.[7]

Scheme 1.

The observation that acetolysis of either 3-phenyl-2-pentyl brosylate (1-OBs, Scheme 1) or 2-phenyl-3-pentyl brosylate (2-OBs) gave identical mixtures of the corresponding acetates provided early evidence for the formation of the bridging phenonium ion intermediate 2+.[3] Our work has focused on the solvolysis and nucleophilic substitution reactions of carbon-13 labeled ring-substituted 2-phenylethyl tosylates (X-3-[α-13C]OTs) in aqueous solution through the symmetrical bridged phenonium ion X-4+ (Scheme 2), where the extent scrambling of label in the solvent (X-3-OSolv) and nucleophile (X-3-Nu) adducts is quantified by [13C]-NMR.[8–10]

Scheme 2.

The strong stabilization of phenonium ion H-4+ by a 4-MeO substituent enables the generation of MeO-4+ from MeO-3-Cl by ionization using SbF5 in SO2 (Scheme 3A). The NMR spectrum of MeO-4+ is unexceptional and shows the expected three types of protons: four cyclopropyl –H at 3.47 ppm; the –OCH3 at 4.25 ppm, and protons from the A2B2 quartet at 7.47 and 8.12 ppm.[11] One important question is whether the phenonium ion should be treated as a classical spiro[2.5]oct-5,7-diene-4yl carbocation H-4+, or if there is also a substantial contribution from the nonclassical resonance structure H-5+ (Scheme 3B), where only two bonding electrons are used in a 3-centered bond to cyclopropyl carbon atoms.[12] This bonding is exemplified by the 2-norbornyl carbocation 6+.[13] The 13C chemical shift of the ipso carbon of H-4+ would appear to define its hybridization of sp3.[14] A theoretical study from 1993, which concluded that H-4+ was a non classical carbocation,[15] was disputed by Olah and coworkers on the basis of NMR studies and their own theoretical calculations.[16] The bonding in phenonium ions was examined by the B3LYP/6-31G* calculations.[17] The analysis of the Kohn-Sham orbitals and a Bader analysis of the computed electron density of H-4+ shows that the three membered ring is formed by back-bonding from the ethylene fragment to the phenyl cation moiety.[17] It was suggested that the bonding interactions between the cationic moiety and ethylene take place so that the shielding of the ipso carbon is similar to that for an sp3 center, but that the aromatic system is preserved and even “enlarged by the incorporation of the C2H4 fragment.”[17]

Scheme 3.

Nucleophilicity of the aromatic ring

MeO-3-Cl undergoes an intramolecular nucleophilic displacement, where the loss stabilizing aromaticity at the neutral reactant is partially compensated by resonance stabilization of the cyclohexadienyl carbocation product (Scheme 3A).[18] The carbon nucleophilicity of the benzene ring is enhanced by electron donation from the 4-OMe substituent, which acts to stabilize the cyclohexadienyl carbocation fragment of the phenonium ion. For example, a Yukawa-Tsuno treatment of rate constants for acetolysis of 2-phenylethyl tosylates X-3-OTs through phenonium reaction intermediates (Scheme 3B) gives values of ρ = 3.9 and r = 0.63.[19–21] The values for the Hammett ρ and the Yukawa-Tsuno parameter r are smaller than for the reference solvolysis reactions of cumyl chlorides.[22–24] This is consistent with a transition state for solvolysis of X-3-OTs, where electron donation from 4-X is attenuated and the effective positive charge “seen”[25, 26] by the ring substituents reduced in comparison to the reference SN1 solvolysis.[27, 28]

Neutral phenol undergoes competitive O- and C-alkylation at carbon by the 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl carbocation (MeO-7+, Scheme 4) to give a 20/1 yield of the products of alkylation at oxygen and the C-4 carbon (Scheme 4).[29] This is consistent with a Mayr nucleophilicity parameter of N = 2.0 for the C-4 of phenol.[29, 30] 2-Hydroxyethyl tosylate has been prepared and used as an alkylating agent.[31, 32] It would be of interest to know the relative rates for cyclization of this tosylate to form the epoxide and for cyclization of MeO-3-OTs to form the phenonium ion MeO-4+ (Scheme 5).

Scheme 4.

Scheme 5.

Thermodynamic stability of the phenonium ion

The thermodynamically favorable isomerization of 2,4,6 trimethyl phenonium ion in the superacidic medium SbF5/SO2 to the 1-(2,4,6 trimethylphenyl)ethyl carbocation has been observed.[11] A driving force of for isomerization of H-4+ to H-7+ (Scheme 6) in a solvent with a relative permittivity of 40 was determined by quantum chemical calculations.[17] By comparison, the thermodynamic parameters for isomerization of H-3-OH to H-7-OH are estimated to be , Scheme 6), using thermochemical data for the group contributions of Benson and coworkers, and assuming ,[33, 34] The thermodynamic barrier for generation of H-4+ from the corresponding 2-phenylethyl alcohol H-3-OH is then calculated to be 6 kcal/mol more positive ( ) than determined for ionization of H-7-OH in a mixed aqueous/trifluoroethanol water solvent,[28] if possible solvent effects are neglected. It is interesting that the cyclopropyl ring strain released upon isomerization of H-4+ to H-7+ [≈ −27 kcal/mol][35] is 15 kcal/mol greater than the overall −12 kcal/mol reaction driving force. This difference may reflect a smaller ring strain at H-4+ compared with cyclopropane and/or a greater total resonance stabilization of H-4+ compared with the 1-phenylethyl carbocation H-7+.

Scheme 6.

Lifetimes of X-4+

Determination by direct methods

There are three requirements for the generation and determination of the lifetimes of reactive intermediates, such as X-4+, in a nucleophilic solvent (Scheme 7).[36] (1) A fast photochemical reaction to generate the cation must be identified. (2) Methods to monitor the formation and decay of the cation must be developed. (3) The lifetime of the cation (1/ks, s) must be sufficiently long to allow decay of the cation to be monitored. We are not aware of any successful determination of the lifetime of X-4+ in solution, or rate constant ks (Scheme 7) for a nucleophile addition reaction.

Scheme 7.

An experimental protocol has been developed, which may serve as a starting point for these lifetime determinations. The 4-methoxyphenylium ion 8+ was generated by photolysis of 4-chloroanisole in polar media and detected by flash photolysis (Scheme 8). When this photochemical reaction is carried out in a polar solvent in the presence of dimethylbutene a β-alkoxyanisole product is isolated, which is thought to arise from trapping by trifluoroethanol of the sufficiently long-lived 4-methoxy substituted phenonium ion 9+.[37, 38]

| (1) |

Scheme 8.

Azide ion clock

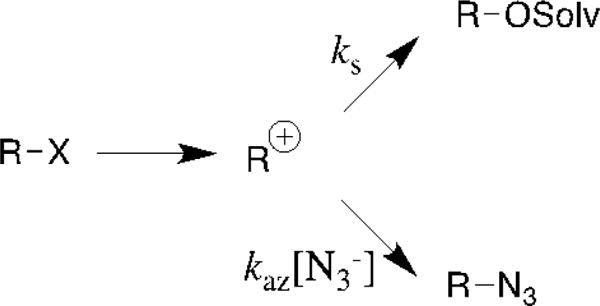

Carbocations generated by DN + AN reactions[39] in a nucleophilic solvent that contains azide ion react to form a mixture of the solvent and azide ion adducts (Scheme 9). The ratio of the yields of these adducts defines the nucleophile selectivity kaz/ks, M−1 (eq 1) for the carbocation R+. A sharp decrease in kaz/ks, with increasing electrophile reactivity (Figure 1) is observed for the partitioning of ring-substituted 1-phenylethyl,[28, 40] 1-(phenyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl,[41–43] and cumyl carbocations.[44] In each case the fast addition of azide anion serves as a “clock” for the slower reaction of solvent: the rate constant ks for solvent addition may be estimated from the value of kaz/ks using kaz = kd ≈ 5 × 109 M−1 s−1 (Figure 1) for the diffusion limited reaction of azide anion.[45] Scheme 10 shows representative carbocations, whose lifetime’s 1/ks have been determined using the azide ion clock.[28, 41, 46–52] This azide ion clock also provides lifetimes for carbocation-anion pairs in water.[53–60]

Scheme 9.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical plot of azide ion selectivity kaz/ks (M−1) against the reactivity of the carbocation intermediate of solvolysis of R-X (Scheme 9). The descending limb on the left hand side of this plot is for reactions where the carbocation lifetime 1/ks (s) is decreasing relative to the constant second-order rate constant kaz (M−1 s−1) for diffusion-limited addition of azide ion to the carbocation.

Scheme 10.

| (2) |

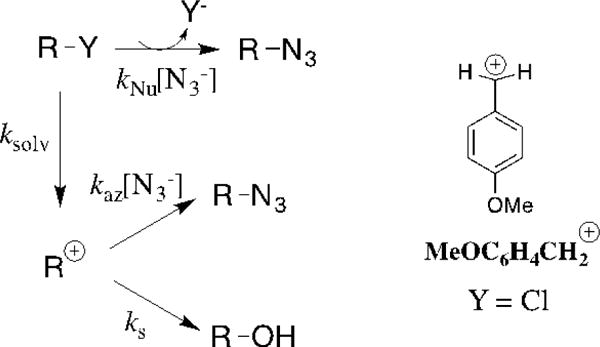

The product yields from reactions of ring-substituted 2–phenylethyl derivatives X-3-Y in nucleophilic solvents that contain azide anion give the observed azide anion selectivity (kaz/ks)obs. The problem then is to separate this observed ion selectivity into the contributions from the stepwise (kaz/ks) and concerted bimolecular nucleophilic substitution (kNu/ksolv) reactions of azide anion (Scheme 11). The following protocol was developed to determine these rate constant ratios for the concurrent stepwise (DN + AN) and concerted (ANDN)[39] reactions of MeOC6HCH2Cl.[50]

Scheme 11.

The effect of increasing [N3−] on the observed first-order rate constant kobs for the disappearance of MeOC6H4Cl was determined. The value of kNu/ksolv = 15 M−1 for the bimolecular substitution reaction in 80:20 (v/v) acetone:water was obtained as the ratio of the slope (kNu, M−1 s−1) and intercept (ksolv, s−1) of the plot of kobs against [N3−].

Product nucleophile selectivities of (kaz/ks)obs > kNu/ksolv were determined for the reaction of MeOC6H4CH2Cl in 80:20 (v/v) acetone:water. This shows that MeOC6H4CH2Cl reacts with azide anion by concurrent stepwise and concerted pathways (Scheme 11). The values of (kaz/ks)obs increase linearly with increasing [N3−] (not shown). The slope and intercept of this linear correlation are equal to and from eq 2. The value of kaz/ks = 8 M−1 for partitioning of MeOC6H4CH2+ (Scheme 11) was determined from the linear least-squares fit of these product rate constant ratios to eq 2 using kNu/ksolv = 15 M−1 (above) for the bimolecular nucleophilic substitution reaction of azide anion.[50]

A related analysis of the effect of increasing [N3−] on the rate and products of the reaction of MeO-3-OTs in 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O (I = 0.5, NaClO4) and at 25 °C gave the rate constant ratios for the several pathways shown in Scheme 12, except that for these reactions the unlabeled substrate was examined.[10]

Scheme 12.

The slope and intercept of a linear plot of kobs, determined by monitoring the disappearance of MeO-4-OTs, gave the rate constant ratio of kNu/kΔ = 1.9 M−1 for the bimolecular (kNu) and the stepwise nucleophilic substitution reactions (kΔ).

The dependence of the product selectivity (kaz/ks)obs on [N3−] (Figure 2) is more complicated than the linear dependence observed for reactions of MeOC6H4CH2Cl. The product rate constant ratios (kaz/ks)obs ranged from 90 – 100 M−1, and are much larger than kNu/kΔ = 1.9 M−1 from the kinetic experiment. This shows that MeO-4-N3 forms mainly by trapping of the phenonium ion intermediate MeO-4+. The downward curvature for the plot of (kaz/ks)obs against [N3−] (Figure 2) requires an additional pathway for azide ion catalysis of direct solvent addition to MeO-4-OTs (Scheme 12). The product data from Figure 2 were fit to a complex equation (not shown) to obtain values of kaz/ks = 83 M−1 and kB/kNu = 0.016.

Figure 2.

The effect of increasing [N3−] on the rate constant ratio (kaz/ks)obs obtained from the yields of the products of nucleophilic addition of azide anion and solvent to MeO-3-OTs in 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O (I = 0.5, NaClO4) and at 25 °C. Reprinted with permission from Ref 10. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

A second protocol provides an independent check of these nucleophile selectivities for partitioning of MeO-4+ and Me-4+. The carbon-13 labeled substrates MeO-1-[α–13C]OTs and Me-1-[α–13C]OTs were prepared, and the reaction products examined by carbon-13 NMR to determine the extent of scrambling of carbon-13 label between the α– and β–carbon (fα + fβ = 1.0). This distribution defines the product yields by stepwise and concerted reactions pathways (Scheme 12), because MeO-1-[β-13C]Nu (Nu = −N3 or –OSolv) only forms by partitioning of the phenonium ion intermediate MeO-4+. The total product yield from the reaction of this intermediate [(fR-Nu)Δ] is equal to the two times the yield of MeO-1-[β-13C]Nu ((fR-Nu)Tfβ, eq 3), while the yield from the concerted reaction [(fR-Nu)con] is equal to the difference between the yields of MeO-1-[α-13C]Nu and MeO-1-[β-13C]Nu. (eq 4). The product yields determined from eq 3 and 4 were used to obtain the rate constant ratios (Scheme 12) for the stepwise (eq 5) and concerted (eq 6) reactions in 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O. The rate constant ratios for reactions of Me-1-[α–13C]OTs and MeO-1-[α–13C]OTs determined from the distribution of label at the α and β carbon atoms of the reaction products (Scheme 12) are in good agreement with the ratios determined from the rate and product analyses described above for the reactions of unlabeled MeO-1-OTs and Me-1-OTs.[9, 10]

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

The nucleophile selectivities kaz/ks for partitioning of X-4+ between addition of azide anion and the common solvent of 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O are summarized in Chart 1. The selectivities for X-7+ show a sharp 100-fold decrease, with increasing carbocation reactivity, as the ring substituent X is changed from 4-OMe to 4-Me, and the value of ks increases relative to the constant kaz = kd ≈ 5 × 109 M−1 s−1 for the diffusional trapping reaction of azide anion. This change from X = 4-OMe to X = 4-Me is expected to cause the same large change in the nucleophile for MeO-C6H4CH2+. By contrast, the selectivity for partitioning of X-4+ decreases by < 3-fold [83 to 38 M−1] for a change in ring-substituent from 4-OMe to 4-Me. We expected that this change in ring substituent would cause a >> 3-fold increase in the absolute rate constant for addition of solvent to the strongly resonance stabilized phenonium ion Me-4+. The small decrease in kaz/ks reflects the larger increase, with increasing cation reactivity, in ks compared with kaz << 5 × 109 M−1 s−1. The diffusional rate constant therefore only sets an upper limit on ks for solvent addition to X-4+.[9]

Chart 1.

Lifetime of phenonium Ions

The rate constants for capture of neutral spiro[2.5]oct-4,7-diene-6-one 10 (ks = 3.4 × 10−3 s−1)[61] and p-quinone methide 11 (ks = 3.3 s−1) by water provide a point of reference for the estimation of rate constants for addition of water to the more reactive X-4+ (Chart 2). The value of ks = 2 × 108 s−1 [50] for addition of 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O to MeOC6H4CH2+ and the assumption that the 1000-fold difference in reactivity for neutral 10 and 11 is also observed for the O-methylated carbocations MeOC6H4CH2+ and MeO-4+ gives ks ≈ 2 × 105 s−1 for addition of solvent to MeO-4+. This corresponds to a lifetime of several μsec. The rate constant ratio (kaz/ks) = 83 M−1 then gives kaz ≈ 2 × 107 M−1 s−1 (Chart 1). The rate constant for addition of 50/50 (v/v) TFE/H2O to MeC6H4CH2+ has not been determined, but should be greater than ks = 6 × 109 s−1 for solvent addition the more stable 1-(4-methylphenylethyl) carbocation (X-7+).[62] This allows rough estimates of ks ≈ 107 s−1 and kaz ≈ 3 × 108 M−1 s−1 for reactions of Me-4+ reported in Chart 1. These estimates suggest that the lifetimes of X-4+ are long enough to allow their determination by direct measurement.

Chart 2.

Mechanism for Nucleophile Addition to Phenonium Ions

We now look past the similarities in the absolute reactivity and charge delocalization of X-7+ and X-4+, and consider the effect of differences in the structures of these cations on the kinetic barrier to nucleophile addition reactions. The trivalent cationic carbon at MeOC6H4CH2+ is stabilized by direct electron donation from the aromatic ring to the benzylic center. The intrinsic barrier to this nucleophile addition is related to the barrier for the reorganization of electron density from the reactant cationic carbon of the product aromatic ring.[63–65] However, the barrier to nucleophile addition to X-4+ reflects not only that for electronic reorganization, but also the barrier associated with formation of a metastable pentavalent species in which there are five partial bonds to carbon.[66, 67] The barrier for addition of azide ion to Me-4+ (kaz ≈ 3 × 108 M−1 s−1) is unusually small for bimolecular aliphatic substitution at carbon. The concerted reaction mechanism for addition of azide anion is “enforced” because the lifetime of the primary carbocation intermediate of the stepwise reaction (X-3+, Scheme 13) is shorter than that for a bond vibration.[68–72] The small barrier to addition of azide anion reflects the balance between the large favorable driving force for cleavage of the strained cyclopropyl ring at X-4+ and for restoration of aromaticity, the small stabilization from partial bond formation to the azide anion nucleophile, and the energetically demanding shift of positive charge onto the central primary carbon at the exploded transition state described below.

Scheme 13.

The small 2.6-fold change in nucleophile selectivity from kaz/ks = 83 M−1 for MeO-4+ to 32 M−1 for Me-4+[8] reflects the shift, with decreasing pKa of the carbon leaving group, to a “looser” transition state with weakened bonding of the nucleophile and leaving group to the central carbon, as has been observed and rationalized for other nucleophilic aliphatic substitution reactions.[73, 74] The selectivities (kNu/ks) determined for reactions of 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)ethyl tosylate (MeO-1-OTs) and 2-(4-methyphenyl)ethyl tosylate (Me-1-OTs) with several nucleophilic anions in 50/50 (v/v) trifluoroethanol/water at 25 °C give logarithmic Swain-Scott plots that are correlated by slopes of s = 0.78 and s = 0.73 for reactions of MeO-4+ and Me-4+, respectively,[8] so that the sensitivity of bimolecular substitution at X-4+ to changes in nucleophile reactivity is smaller than for the reference nucleophilic substitution reactions at methyl iodide for which s = 1.0.[66, 75]

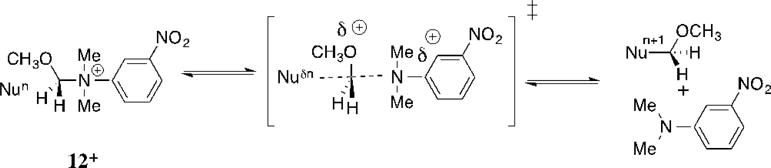

Brønsted coefficients of βnuc = 0.09 and 0.06, respectively, for MeO-4+ and Me-4+ were determined as the slope of a logarithmic correlation of nucleophile selectivity (kRCOO/ks) for substitution reactions (Scheme 13) of CH3CO2− (pKa = 4.8) and CHCl2CO2− (pKa = 1.3). Larger coefficients of βnuc = 0.14 and 0.13 were reported, respectively, for nucleophilic substitution reactions of substituted alkyl amines at N-(methoxymethyl)-N,N-dimethyl(3-nitroanilinium) ion (12+, Scheme 14),[76] and for nucleophilic substitution reactions of substituted alkyl alcohols at (1-4-nitrophenyl)-2-propyl tosylate.[77]

Scheme 14.

These results are consistent with “exploded” transition state structures for nucleophile addition to MeO-4+, and a large positive charge development at the central carbon, due to the weak bonding of the nucleophile and leaving group at the pentavalent transition state.[72, 76] They may be rationalized using two-dimensional structure-reactivity diagrams, which assign separate coordinates to bond formation between the nucleophile (C-Nu) or leaving group (C-LG) and the central carbon atom.[74, 78, 79] In the case of nucleophilic substitution at 12+ (Scheme 14), the “exploded” transition state reflects an anti-Hammond shift of the transition state towards the carbocation reaction intermediate, where there is full charge stabilization by the α-alkoxy group.[74, 76] In the case of substitution at X-4+ (Scheme 13) the “exploded” transition state is favored because it allows for relief of cyclopropyl ring strain and the development of aromaticity at the leaving group: this is sufficient to drive positive charge onto central primary carbon.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (GM 39754) for generous support of this work.

References

- 1.Cram DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1949;71:3863. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saunders M, Kronja O. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2004:213. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cram DJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1949;71:3875. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Lee YG, Jagannadham V. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:10833. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancelot CJ, Cram DJ, Schleyer PvR. In: Carbonium Ions. Olah GA, Schleyer PvR, editors. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1972. p. 1347. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capon B, McManus SP. Neigboring Group Participation. Vol. 1. Plenum Press; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prakash GKS, Reddy VP. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2004:73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsuji Y, Richard JP. Can J Chem. 2015;93:428. doi: 10.1139/cjc-2014-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji Y, Ogawa S, Richard JP. J Phys Org Chem. 2013;26:970. doi: 10.1002/poc.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsuji Y, Hara D, Hagimoto R, Richard JP. J Org Chem. 2011;76:9568. doi: 10.1021/jo202118s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olah GA, Comisarow MB, Namanworth E. J Am Chem Soc. 1967;89:5259. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winstein S. In: Carbonium Ions. Olah GA, Schleyer PvR, editors. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1972. p. 965. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sargent GD. In: Carbonium Ions. Olah GA, Schleyer PvR, editors. Vol. 3. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1972. p. 1099. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olah GA, Porter RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1970;92:7627. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sieber S, Schleyer PvR, Gauss J. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:6987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olah GA, Head NJ, Rasul G, Prakash GKS. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:875. [Google Scholar]

- 17.del Rio E, Menendez ML, Lopez R, Sordo TL. J Phys Chem A. 2000;104:5568. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cozens F, Li JH, McClelland RA, Steenken S. Angew Chem, Int Ed Engl. 1992;31:743. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujio M, Funatsu K, Goto M, Seki Y, Mishima M, Tsuno Y. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1987;60:1091. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yukawa Y, Tsuno Y, Sawada M. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1966;39:2274. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yukawa Y, Tsuno Y. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1959;32:971. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown HC, Brady JD, Grayson M, Bonner WH. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:1897. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okamoto Y, Brown HC. J Am Chem Soc. 1958;80:4976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoefnagel AJ, Wepster BM. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:5357. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams A. Adv Phys Org Chem. 1992;27:1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hupe DJ, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:451. doi: 10.1021/ja00467a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young PR, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:3288. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richard JP, Rothenberg ME, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1361. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuji Y, Toteva MM, Garth HA, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15455. doi: 10.1021/ja037328n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phan TB, Breugst M, Mayr H. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:3869. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradshaw JS, Krakowiak KE, LindH GC, Izatt RM. Tetrahedron. 1987;43:4271. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsutsumi H, Inoue K, Ishido Y. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1979;52:1427. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hine J. Structural Effects on Equilibria in Organic Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benson SW, Cruickshank FR, Golden DM, Haugen GR, O’Neal HE, Rodgers AS, Shaw R, Walsh R. Chem Rev. 1969;69:279. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fuchs R. J Chem Ed. 1984;61:131. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClelland RA. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:6823. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Protti S, Dondi D, Mella M, Fagnoni M, Albini A. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;17:3229. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manet I, Monti S, Grabner G, Protti S, Dondi D, Dichiarante V, Fagnoni M, Albini A. Chem Eur J. 2008;14:1029. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guthrie RD, Jencks WP. Acc Chem Res. 1990;23:270. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richard JP, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4689. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:1455. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:6819. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Bei L, Stubblefield V. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9513. doi: 10.1021/ja00182a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Vontor T. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:5871. [Google Scholar]

- 45.McClelland RA, Kanagasabapathy VM, Banait NS, Steenken S. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:1009. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richard JP, Toteva MM, Amyes TL. Org Lett. 2001;3:2225. doi: 10.1021/ol016103j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toteva MM, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:11434. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amyes TL, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:7888. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amyes TL, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3677. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:9507. doi: 10.1021/ja00182a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Stevens IW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4255. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amyes TL, Richard JP. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1991;200 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teshima M, Tsuji Y, Richard JP. J Phys Org Chem. 2010;23:730. doi: 10.1002/poc.1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsuji Y, Toteva MM, Amyes TL, Richard JP. Org Lett. 2004;6:3633. doi: 10.1021/ol0484409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Toteva MM, Tsuji Y. Adv Phys Org Chem. 2004;39:1. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386047-7.00002-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsuji Y, Mori T, Toteva MM, Richard JP. J Phys Org Chem. 2003;16:484. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsuji Y, Mori T, Richard JP, Amyes TL, Fujio M, Tsuno Y. Org Lett. 2001;3:1237. doi: 10.1021/ol015706s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richard JP, Tsuji Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3963. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tsuji Y, Richard JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:17139. doi: 10.1021/ja066235d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsuji Y, Richard JP. Chem Rec. 2005;5:94. doi: 10.1002/tcr.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baird R, Winstein S. J Am Chem Soc. 1957;79:4238. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Richard JP, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1373. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Toteva MM. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:981. doi: 10.1021/ar0000556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richard JP, Amyes TL, Williams KB. Pure Appl Chem. 1998;70:2007. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richard JP. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:1535. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pearson RG, Sobel H, Sonstad J. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:319. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pearson RG, Songstad J. J Org Chem. 1967;32:2899. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jencks WP. Chem Soc Rev. 1981;10:345. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jencks WP. Acc Chem Res. 1980;13:161. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dietze PE, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2057. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dietze PE, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:4549. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richard JP, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:1383. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lewis ES, Vanderpool SH. J Am Chem Soc. 1978;100:6421. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jencks WP. Chem Rev. 1985;85:511. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Swain CG, Scott CB. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:141. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Knier BL, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:6789. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dietze P, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:5880. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jencks DA, Jencks WP. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:7948. [Google Scholar]

- 79.More O’Ferrall RA. J Chem Soc (B) 1970:274. [Google Scholar]