Abstract

Despite global reductions in HIV incidence and mortality, the 15 UNAIDS-designated countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) that gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 constitute the only region where both continue to rise. HIV transmission in EECA is fuelled primarily by injection of opioids, with harsh criminalisation of drug use that has resulted in extraordinarily high levels of incarceration. Consequently, people who inject drugs, including those with HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis, are concentrated within prisons. Evidence-based primary and secondary prevention of HIV using opioid agonist therapies such as methadone and buprenorphine is available in prisons in only a handful of EECA countries (methadone or buprenorphine in five countries and needle and syringe programmes in three countries), with none of them meeting recommended coverage levels. Similarly, antiretroviral therapy coverage, especially among people who inject drugs, is markedly under-scaled. Russia completely bans opioid agonist therapies and does not support needle and syringe programmes—with neither available in prisons—despite the country’s high incarceration rate and having the largest burden of people with HIV who inject drugs in the region. Mathematical modelling for Ukraine suggests that high levels of incarceration in EECA countries facilitate HIV transmission among people who inject drugs, with 28–55% of all new HIV infections over the next 15 years predicted to be attributable to heightened HIV transmission risk among currently or previously incarcerated people who inject drugs. Scaling up of opioid agonist therapies within prisons and maintaining treatment after release would yield the greatest HIV transmission reduction in people who inject drugs. Additional analyses also suggest that at least 6% of all incident tuberculosis cases, and 75% of incident tuberculosis cases in people who inject drugs are due to incarceration. Interventions that reduce incarceration itself and effectively intervene with prisoners to screen, diagnose, and treat addiction and HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis are urgently needed to stem the multiple overlapping epidemics concentrated in prisons.

Introduction

The negative and mutually reinforcing nature of incarceration, substance use disorders, and blood-borne viruses such as HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis is especially problematic in the 15 UNAIDS-designated countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA), and results in a concentration and deleterious interaction between these comorbid health and social conditions.1,2 EECA is now the only region where the number of new HIV infections has increased annually, from 120 000 to 190 000 between 2010 and 2015, resulting in the number of people with HIV increasing from 1.0 million to 1.5 million in the same period.3 Although new WHO guidelines recommend treatment for all people living with HIV irrespective of CD4 count, coverage with antiretroviral therapy in the region is less than 10%4 and is compounded both by suboptimal screening for diseases and low coverage of evidence-based HIV prevention strategies (eg, opioid agonist therapies with methadone or buprenorphine, or needle and syringe programmes).5,6

In EECA, proscriptive policies that promote arrest of socially vulnerable individuals at increased risk of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis (eg, people who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, and sex workers) result in a concentration of risk within prisons, which amplifies disease and leads to onwards transmission in the community after release.7 These epidemics converge in the EECA region, where abrupt and far-reaching social, economic, and political transitions since the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 have resulted in poor public health consequences. Where such negatively reinforcing comorbidities exist, effective HIV prevention and treatment must address all problems simultaneously to have a noticeable effect.1 Yet, the HIV response remains inadequate as HIV incidence and mortality continue to increase in EECA, despite reductions worldwide.3

Although EECA countries are culturally and religiously distinct and have undergone different political, economic, and social trajectories since independence, they share sociopolitical, philosophical, and organisational vestiges of the former Soviet Union, which now shape the evolving synergistic epidemics (also known as syndemics) of mass incarceration, substance use disorders, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis. Aside from the high-income countries of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia, the 12 other EECA countries are low-income or middle-income countries. Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, in this setting of political and economic instability, heroin entered through new trade routes from Afghanistan.8,9 Use of injected heroin increased and led to explosive HIV transmission among people who inject drugs, where the epidemic remains mostly concentrated today. Harsh drug policies and criminalisation laws ensued targeting people who inject drugs, with resultant mass incarceration, prison overcrowding10 and high incarceration rates (five of the highest ten globally).11 The concentration of people who inject drugs, people living with HIV with compromised immune systems, and individuals with tuberculosis in criminal justice systems creates especially high-risk environments for HIV and tuberculosis transmission.12–14 The unresponsive health authorities, unaccustomed to implementing HIV and tuberculosis prevention and treatment in prison settings, did not meet human rights recommendations.

Data have not, however, been comprehensively synthesised to understand how the criminal justice system contributes to the expanding HIV and related epidemics in EECA. In this Series paper, we apply the risk environment framework to describe how incarceration, HIV, hepatitis C virus, tuberculosis, and substance use disorders converge to produce drug-related harm and clarify how individual HIV risk behaviours are embedded within social processes, specifically incarceration within EECA.15,16 Further, mathematical modelling and statistical analyses are used to estimate the degree to which incarceration contributes to HIV and tuberculosis transmission among people who inject drugs in Ukraine, and analyse the effectiveness of evidence-based HIV prevention strategies in reducing the harms of incarceration.

Methods

Analytical framework

In this comprehensive review, we aimed to review the historical features occurring during a devastating transitional period after the dissolution of the Soviet Union that now shape the concurrent epidemics of incarceration, HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis in EECA; present a theoretical framework—termed the “risk environment”—for understanding how the criminal justice system, including policing and incarceration practices, influences the evolving HIV and tuberculosis epidemics; provide an analysis of up-to-date legal, criminal justice, and epidemiological data from the 15 countries of EECA; use detailed data from Ukraine to estimate the degree to which incarceration contributes to HIV transmission among people who inject drugs (using dynamic mathematical modelling) and tuberculosis transmission among people who inject drugs and the general population (using statistical analyses); and recommend new directions for prevention, treatment, and research.

Here, we examine how the risk environment within the criminal justice system synergistically reinforces, concentrates, and amplifies the effect of several medical conditions (eg, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis). This is not only affected by social conditions (eg, incarceration, poverty) but also includes the policing practices that influence arrest and entry into the criminal justice system and the experiences within the prison environment itself, which result in the syndemic of social and medical comorbidities. The amplification of drug-related harm in prisons17–19 is best understood using the risk environment framework.15 This conceptual model posits that individual decisions about disease prevention and treatment are rooted in structural risk such as spaces (in this case, prisons) that, while exogenous to the individual, independently contribute to risk-taking and health-seeking behaviours. Hierarchical social structures within the criminal justice system, interpersonal violence, and the lack of safety, stigma, privacy, and autonomy often limit decision making by prisoners, including choices about health-care engagement and drug use.16,20 Access to prison-Wbased HIV and other health-care services (eg, opioid agonist therapy), and the capacity to reduce drug-related harm, is affected by these environmental factors at the social, economic, and political levels.21

Survey methods

In most EECA countries, access to accurate prison-related data and formal and informal operations of the penitentiary systems is limited. We therefore aimed to compile data about prisoner health and access to health services focusing on drug-related and comorbid conditions, and to compile supplemental survey information from prison medical departments with assistance from the United Nations Office on Drug Control (UNODC) using official governmental requests in each country. Among 15 surveys requested, 11 responded, with findings included in tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Overview of prison populations in Eastern Europe and Central Asia

| Azerbaijan | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Turk- menistan |

Uzbekistan | Russia | Ukraine | Belarus | Moldova | Lithuania | Latvia | Estonia | Armenia | Georgia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prison population | 16 500* | 44 893 | 7961 | 9000* | 30 568 | 42 000* | 656 618 | 57 396 | 31 700 | 5329 | 6634 | 3276 | 2775 | 3894 | 9724 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Estimated number of people who inject drugs | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 71 283 | 116 840 | 25 000 | 25 000 | .. | 80 000 | 1.8 million | 332 500 | 75 000 | 30 200 | 5403 | 10 034 | 9000 | 3310 | 45 000 |

| Prison | 31.9% | .. | 30.4% | .. | .. | .. | .. | 48.7% | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 5.5% | .. |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Antiretroviral therapy coverage | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 14% | 4639 | 13% | 10% | .. | 24% | 178 711 | 26% | 21% | 17% | 542 | 1055 | 2998 | 16% | 39% |

| Prison | 63.2% | 34.3% | 69.9% of those registered | 59.1% | .. | .. | 5.0% | 6.4% | .. | 63.1% | 23.2% | 19.3% | .. | 77.3% | 87.5% |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HIV prevalence | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.4% | <0.2% | 0.2% | 1.1% | 1.2% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 0.2% | 0.3% |

| Prison | 3.7% | 3.9% | 10.3% | 2.4% | 0 | 4.7% | 6.5% | 19.4% | .. | 2.6% | 3.4% | 20.4% | 14.1% | 2.4% | 0.90% |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Tuberculosis incidence or prevalence per 100 000 | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 77 | 99 | 142 | 91 | 64 | 82 | 84 | 94 | 58 | 153 | 62 | 49 | 20 | 45 | 106 |

| Prison | 152 | 2110 | 145 | 162 | 184 | 58 | 69 | 56 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Opioid-dependent individuals | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 1.5% | 1.0% | 0.80% | 0.54% | .. | 0.80% | 2.3% | 0.91% | 0.59% | .. | 0.24% | 0.66% | .. | 0.16% | 1.36% |

| Prison | 32.5% | 3.0%‡ | 13.7% | 5.0% | .. | .. | .. | 44.3% | .. | 6.6%† | 7.6% | 30.0% | .. | .. | .. |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Number of opioid agonist therapy sites | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 2 | 10 | 23 | 6 | .. | .. | .. | 169 | 19 | 3 | 23 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 21 |

| Prison | .. | .. | 7 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 9 | .. | 9 | 4 | 9 | 2‡ |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Number of individuals receiving opioid agonist treatments | |||||||||||||||

| Community | 137 | 205 | 1227 | 677 | .. | .. | .. | 8264 | 1066 | 392 | 930 | 424 | 919 | 430 | 2600 |

| Prison | .. | .. | 400 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 68 | .. | 26 | 56 | 151 | .. |

All values are from the survey administered for this study in collaboration with UNODC and refer to 2015, unless otherwise specified in the appendix. UNODC=United Nations Office on Drug Control.

Approximate number.

Present only as a pilot programme in SIZO (pre-trial detention) for detoxification and not for maintenance therapy.

Refers only those officially registered as opioid dependent with the National Narcological Registry.

Table 2.

Policies and practices related to HIV infection and harm reduction services in prisons of Eastern Europe and Central

| Azerbaijan | Kazakhstan | Kyrgyzstan | Tajikistan | Turkmenistan | Uzbekistan | Russia | Ukraine | Belarus | Moldova | Lithuania | Latvia | Estonia | Armenia | Georgia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry overseeing prisoner health | Justice | Interior | Prison | Justice | Interior | Interior | Prison | Prison | Interior | Justice | Justice | Justice | Justice | Justice | Prison |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Number of prisons | 35 | 76 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 42 | .. | 146 | .. | 12 | 7 | 11 | .. | 12 | 15 |

| Male | 16 | 69 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 39 | .. | 131 | .. | 10 | 6 | 10 | .. | 11 | 11 |

| Female | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | .. | 15 | .. | 1 | 1 | 1 | .. | 1 | 1 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Number of prisoners | 16 500* | 44 893 | 7961 | 9000* | 30 568 | 42 000* | 656 618 | 57 396 | 31 700 | 5329 | 6643 | 3276 | 2775 | 3894 | 9724 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Proportion female | 2.8%† | 7.7% | 4.0% | 3.3% | 6.5% | 3.0% | .. | 5.6% | .. | 6.6% | 3.7% | 7.4% | .. | 4.5% | 3.3% |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Incarceration rate‡ | 236 | 231 | 181 | 130 | 583 | 152 | 446 | 193 | 306 | 215 | 268 | 239 | 218 | 132 | 274 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Occupancy | 81.4% | 71.8% | 55.5% | 61.5% | 85.0% | 80.0% | 94.2% | 120.24% | 96.8% | 102.9% | 83.1% | 59.5% | 96.3% | 89.3% | 47.8% |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Needle and syringe programmes in prison | No | No | Yes (2005) | Yes (2010) | No | No | .. | No | .. | Yes (1999) | No | No | .. | Yes (2004) | No |

| Number of facilities | .. | .. | 10 | 1 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 10 | .. | .. | .. | 9 | .. |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Opioid agonist therapy | No | No | Yes (2008) | No | No | No | .. | No | .. | Yes (2005) | No | Yes (2012) | .. | Yes (2011) | No |

| Number of facilities | .. | .. | 7 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 9 | .. | 9 | .. | 9 | .. |

| Number of patients | .. | .. | 400 | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | .. | 68 | .. | 26 | .. | 151 | .. |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Detoxification with methadone or buprenorphine | No | No | No | No | No | No | .. | No | .. | Yes | No | No | .. | No | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Non-pharmacological detoxification | Yes | No | Yes | No | .. | No | .. | Yes | .. | No | Yes | Yes | .. | Yes | No |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HIV testing and counselling (year) | Yes | Yes (1997) | Yes (2001) | Yes (2003) | Yes | Yes (2003) | .. | Yes (2006) | .. | Yes (2008) | Yes | Yes (1994) | .. | Yes (2004) | Yes (2004) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Condom provision (year) | Yes (2011) | Yes (2002) | Yes (2005) | Yes (2003) | No | No | .. | Yes (2008) | .. | Yes (1999) | Yes (2004) | No | .. | .. | Yes (2004) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Antiretroviral therapy (year) | Yes (2007) | Yes (2005) | Yes | Yes (2007) | No | Yes (2008) | .. | Yes (2008) | .. | Yes (2004) | Yes | Yes (1998) | .. | Yes (2005) | Yes (2005) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Tuberculosis fluorography (year) | Yes (1995) | Yes (1998) | Yes (1997) | Yes | Yes | Yes (1991) | .. | Yes | .. | Yes (1996) | Yes | Yes (2011) | .. | Yes (2004) | Yes (1998) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| TB treatment (year) | Yes (1995) | Yes | Yes (1998) | Yes | Yes§ | Yes (2004) | .. | Yes | .. | Yes (1996) | Yes (1998) | Yes | .. | Yes | Yes (1998) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HCV diagnostics (year) | Yes (2006) | Yes | Yes (2005) | Yes (2015)¶ | .. | Yes | .. | No | .. | Yes (2004) | Yes | Yes | .. | No | Yes (2014) |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Treatment of HCV | No | No | No | No | .. | No | .. | No | .. | No | Yes (acute only) | No | .. | No | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HBV diagnostics | No | Yes | Yes | .. | .. | Yes | .. | No | .. | Yes | No | Yes | .. | No | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Treatment of HBV | No | No | No | .. | .. | Yes | .. | No | .. | No | No | Yes | .. | No | No |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HBV vaccination | No | No | No | .. | .. | No | .. | No | .. | No | No | No | .. | No | No |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Programmes on prevention of physical and sexual violence | Yes | Yes | No | .. | .. | Yes | .. | No | .. | No | .. | No | .. | Yes | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Staff protection programme against HIV as an occupational hazard | No | Yes | Yes | .. | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | Yes | Yes | .. | No | Yes |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Post-exposure prophylaxis | No | Yes | Yes (2010) | Yes | .. | Yes | .. | No | .. | Yes | No | No | .. | Yes | No |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections | Yes | Yes | Yes | .. | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | .. | Yes | Yes |

All values are from the survey administered for this study in collaboration with UNODC and refer to 2015, unless otherwise specified. Start date is listed in brackets when available. HCV=hepatitis C virus. HBV=hepatitis B virus. UNODC=United Nations Office on Drug Control.

Approximate number.

Number of prisoners per 100 000 population.

People, treated, and tested refer to the total number of people receiving service in 2014.

Available only as a pilot project.

Women and juveniles housed in the same facility.

Modelling the contribution of incarceration to HIV and tuberculosis transmission

We conducted dynamic HIV transmission modelling to assess the long-term contribution of incarceration to HIV transmission among people who inject drugs in Ukraine, and assessed the impact of eliminating incarceration and scaling up of prison-based opioid agonist therapy. Additional statistical analyses were used to estimate the contribution of current or recent incarceration on yearly tuberculosis transmission both in people who inject drugs and in the general population in Ukraine. Modelling and epidemiological methods and results are described in the Ukraine case study, with further details and model equations included in boxes 1 and 2 and the appendix.

Box 1. Modelling the impact of incarceration and scale-up of opioid agonist therapies in prisons on HIV transmission among people who inject drugs in Ukraine.

We developed a national, dynamic model of incarceration and HIV transmission through drug injection that stratified people who inject drugs by incarceration state (never, current, recently released within the past 12 months, and past incarceration more than 12 months ago), and HIV infection state (susceptible, initial acute and chronic HIV infection, and receiving antiretroviral therapy). Within a Bayesian framework,22 the model was calibrated to detailed national data about the incarceration of people who inject drugs (appendix p 3),23–25 and HIV prevalence (appendix p 4) among people who inject drugs who are never-incarcerated (11.9–13.6%), currently incarcerated (22.2–35.4%), and previously incarcerated (26.6–29.7%).23,24,26 Based on the same national data, this calibration assumed elevated injection-related risk of HIV transmission among previously incarcerated people who inject drugs (relative risk 1.9–3.3 within 12 months after release and 1.4–2.0 thereafter; appendix p 5) compared with never-incarcerated individuals. Sensitivity analyses relaxed this assumption. Due to insufficient data, a non-informative prior was used for the transmission risk among incarcerated people who inject drugs.

To estimate the long-term population-attributable fraction (PAF) due to incarceration, the relative decrease in new HIV infections over 15 years was projected when the transmission risk among currently incarcerated and previously incarcerated people who inject drugs was set to the same as never-incarcerated individuals. A conservative PAF assumed the transmission risk among recently released individuals to be the same as previously incarcerated—but not recently incarcerated—people who inject drugs. We also examined how scale-up of opioid agonist therapy to 50% of incarcerated people who inject drugs, with 12-month continuity of opioid agonist therapy after release, could reduce HIV transmission. The appendix pp 1–7 provides more methodological details.

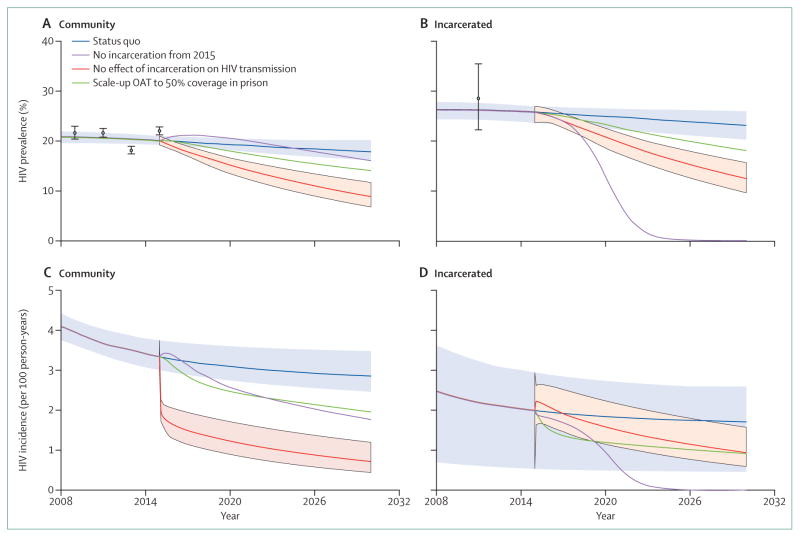

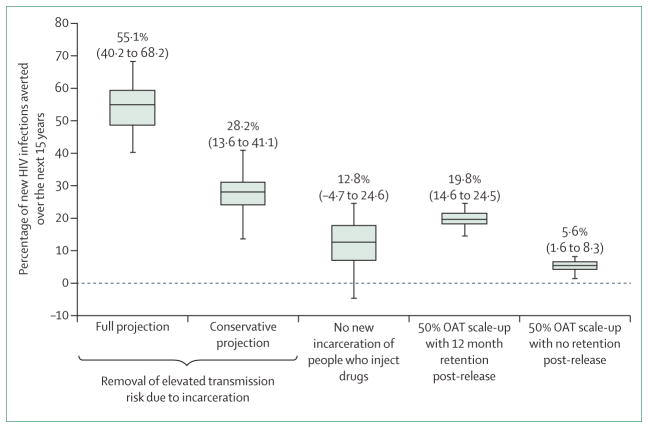

When assuming heightened HIV transmission risk in previously incarcerated individuals who inject drugs, the model (figures 1, 2) suggests that community HIV incidence and prevalence would decrease dramatically by 2030 (incidence by 75% [95% credibility interval (CrI) 64–87], prevalence by 56% [95% CrI 42–66]) if the HIV transmission risk among currently and previously incarcerated individuals were set equal to that of never-incarcerated individuals. Additionally, 55.1% (95% CrI 40.2–68.2) of new HIV infections would be prevented, mainly due to reduction in the heightened risk among recently-released people who inject drugs. Indeed, 28.2% (95% CrI 13.6–41.1) of HIV infections would be averted if this heightened risk was only partly reduced to the same as non-recently incarcerated individuals.

These findings were robust to less restrictive assumptions about the relative transmission risk among previously incarcerated individuals (appendix p 9). By contrast, if people who inject drugs had no new incarcerations after 2015, only 12.8% (95% CrI −4.7 to 24.6) of new HIV infections would be averted thereafter. If prison-based opioid agonist therapies were initiated in Ukraine, however, our modelled scenario suggests 19.8% (95% CrI 14.6–24.5) of HIV infections would be averted during 2015–30, and community coverage of opioid agonist therapy would increase by 8.3%. Much of this effect is due to benefits of retaining prisoners on opioid agonist therapies after release, with only 5.6% (95% CrI 1.6–8.3) of HIV infections being averted without continuation of opioid agonist therapy. Further projections suggest that community coverage levels of opioid agonist therapy (without prison-based opioid agonist therapies) of 28% (95% CrI 20–33), 48% (95% CrI 43–50), or 16% (95% CrI 12–21) would be required to achieve the same impact as scaling up of prison-based opioid agonist therapy, depending on whether this community therapy was untargeted or targeted to never-incarcerated or previously incarcerated individuals, respectively. Considering the prevention benefit per person of opioid agonist therapy, the scenario of prison-based opioid agonist therapy is as efficient as targeting opioid agonist therapy to previously incarcerated people who inject drugs in the community, but is 1.6 times more efficient than untargeted community opioid agonist therapy and 3.2 times more efficient than opioid agonist therapy targeted to never-incarcerated individuals.

These analyses suggest incarceration is a driver of HIV transmission among people who inject drugs in Ukraine, with 55.1% (95% CrI 40.2–68.2) of incident HIV infections possibly attributable to incarceration if we assume all the elevated risk among previously incarcerated people who inject drugs results from incarceration, or 28.2% (95% CrI 13.6–41.1) if we conservatively assume only the additional risk among recently released individuals is due to incarceration.

Importantly, increases in risk behaviours after incarceration fuel the HIV epidemic in Ukraine’s injection drug users, highlighting the need to strategically target HIV prevention interventions to previously incarcerated individuals. Findings here, and confirmed elsewhere, suggest that expansion of prison-based opioid agonist therapy with effective community transition after release could be an effective strategy of achieving this.27–30 Strategies that reduce incarceration, such as alternatives to incarceration (eg, probation, drug courts), community policing that promotes treatment over arrest, and changes in drug criminalisation policies should also be considered, although the HIV benefits may be less.

Our analyses have limitations (detailed in the appendix p 10), most specifically related to whether the elevated transmission risk among previously incarcerated people who inject drugs is due to incarceration or higher-risk individuals being incarcerated frequently; future studies should examine longitudinal changes in risk before, during, and after incarceration.

Box 2. Statistical analyses of the impact of incarceration on tuberculosis transmission in people who inject drugs and more broadly to the general population in Ukraine.

Statistical analyses were performed using national survey data to assess the short-term yearly contribution of incarceration to recent and lifetime tuberculosis transmission among both people who inject drugs and the general public in Ukraine. Detailed methods are provided in the appendix pp 12–13. Data sources included countrywide data from 1612 people who inject drugs in the 2015 ExMAT survey and 402 prisoners in the 2011 PUHLSE survey (appendix pp 12–13).23,25 ExMAT provided individual-level data about incarceration (ever, total time), HIV status, drug injection duration, tuberculosis status in the past 12 months, and ever. PUHLSE provided individual-level data for age, total time incarcerated, HIV status, ever injected drugs, and ever tuberculosis status. Self-reported tuberculosis status was used for all analyses using a validated survey question.31

Using both datasets, linear regression models were firstly developed to evaluate the relationship between ever and recent tuberculosis status and ever being incarcerated or total duration of incarceration. Two survival models were then fitted to data for cumulative tuberculosis risk as a function of time in prison. Using the estimated hazard, an average tuberculosis incidence rate was estimated for each year of incarceration among prisoners (PUHLSE) or previously incarcerated people who inject drugs (ExMAT). The estimated incidence rate among prisoners (PUHLSE) and data for self-reported recent risk of tuberculosis (ExMAT) were then used to estimate the relative risk of tuberculosis among incarcerated people who inject drugs or prisoners overall compared with non-incarcerated individuals who inject drugs or the community as a whole,32 and the population-attributable fraction (PAF) of incarceration to overall tuberculosis risk and tuberculosis risk among people who inject drugs was estimated using standard formula.

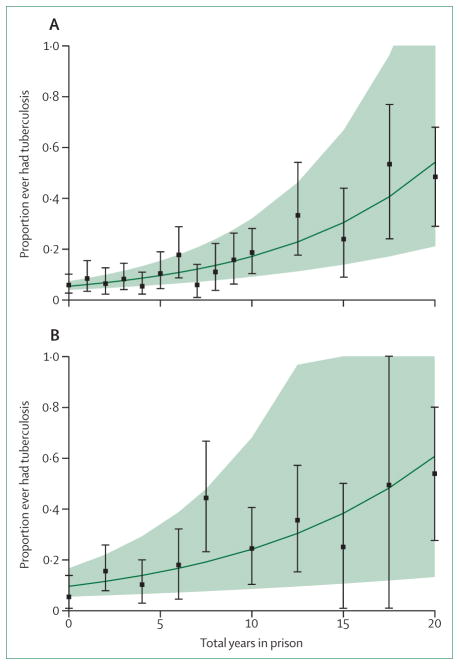

Our analyses consistently suggest that incarceration contributes substantially to tuberculosis transmission in Ukraine. After controlling for age, injecting duration, and other variables, we estimate that for every additional year of incarceration there is a 13% (95% CI 8–17) relative increase in tuberculosis prevalence among the overall population and a 6% (95% CI 3–10) relative increase in tuberculosis prevalence among people who inject drugs (figure 3).

Although only 0.5% of the adult population was incarcerated, we estimate that 6.2% (95% CI 2.2–13.4) of all incident tuberculosis cases result from incarceration. Conversely, among people who inject drugs this increases to 75% (95% CI 51–94) for HIV-infected people who inject drugs and 86% (95% CI 56–98) among HIV-negative people who inject drugs (appendix pp 13–14).

Our analyses from Ukraine indicate that the contribution of incarceration to tuberculosis in the general population was similar to findings from Russia,33 and provides new insights that suggest a markedly higher PAF of incarceration to tuberculosis transmission among people who inject drugs. Although data suggest the importance of incarceration for tuberculosis,12,33–35 there is a paucity of data surrounding the contribution of prison to tuberculosis incidence in low-income and middle-income countries, especially in EECA where tuberculosis incidence is high. Nevertheless, other studies and data presented here suggest that prisons contribute substantially to tuberculosis epidemics broadly, but especially in people who inject drugs in this region (panel 1). Although strategies that reduce incarceration for people who inject drugs would have the greatest impact, these findings also underscore the need to develop cost-effective interventions to diagnose, treat, and prevent tuberculosis transmission among incarcerated populations. Azerbaijan has emerged as a regional leader in implementing such programmes,36 where the government has adopted tuberculosis prevention activities within prison (screening, early detection and treatment, case isolation, and preventive therapy for latent tuberculosis infection). Such strategies, especially if focused on people who inject drugs, should address the increased tuberculosis transmission risk associated with current or previous incarceration. Such strategies, including HIV prevention and treatment, are urgently needed to control the HIV and tuberculosis epidemics in Ukraine and other EECA settings.

Historical framework, organisation of criminal justice, and its influence on EECA

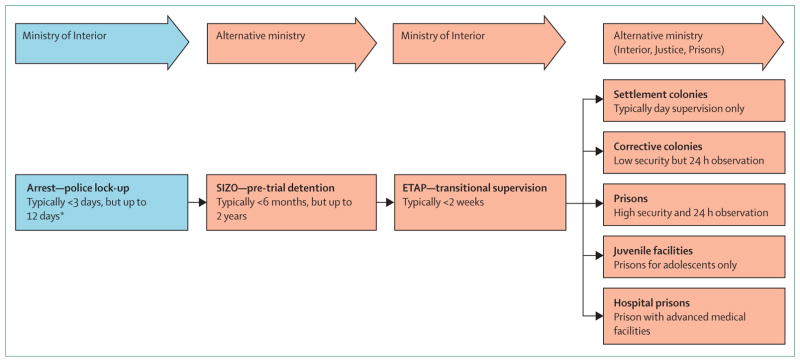

Various governmental ministries other than the Ministry of Health administratively oversee the criminal justice system, including health-care delivery, in all EECA countries (figure 4, table 2). The Ministry of Interior oversees the police, including arrest and short-term detention in lock-up facilities. Health care in pre-trial detention and prisons falls under various ministries, although international organisations such as WHO and UNODC support the separation of oversight of investigations and prosecution from the execution and supervision of criminal sanctions. Although there are various organisational structures for prison health-care delivery across EECA countries, none comply with recommendations by the UN and WHO,37 now known as the Mandela Rules, that stipulate that health care should be equal to that provided within the community and be continuous from prison to community. Some countries, however, have created separate ministries devoted specifically to specialised prisoner supervision.

Figure 4. An overview of the criminal justice system in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

*Anyone arrested may be sentenced and bypass SIZO if convicted immediately.

The criminal justice system in all EECA countries (figure 4), derived from the Soviet system, includes pre-trial detention centres, similar to jails and referred to as SIZO, where detainees remain for up to 2 years while awaiting sentencing. After sentencing, treatment is interrupted by transitional supervision for up to 2 weeks in etap, while awaiting transportation to prison, which is overseen by the Ministry of Interior, followed by placement in penal colonies (including lower-security settlement colonies, and colonies for juvenile offenders) or prisons with cell blocks after sentencing. The separate ministries responsible for oversight at various stages within the criminal justice system, however, often have policies that conflict with each other (eg, regarding allowance or provision of various services). Table 1 compares the prevalence of infectious diseases and harm reduction coverage in prisons and communities in each country. Table 2 and its expanded version in the appendix provide an overview of criminal justice system facilities in each country based on our survey and published reports. Sentenced prisoners are generally divided into minimum-security, medium-security, and maximum-security facilities, which we collectively term “prisons”. Prisoners with HIV are not segregated, but those with tuberculosis are isolated in specialised medical wards.

The legacy of Soviet-style addiction treatment, termed “narcology”,38 prevails in EECA countries and includes ineffective measures such as use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, antipsychotics, excessive physical exercise, neurosurgery, and kinesiotherapy to treat addiction. In Russia, the only criterion of successful addiction treatment is complete abstinence from any psychoactive substance, including from medically prescribed methadone and buprenorphine (which—despite being included on the WHO list of essential medications—remain banned throughout the country). These measures follow the Soviet-era models of repressive psychiatry, contrary to international standards,39 and often amount to suffering, discrimination, and humiliation for drug-dependent people (panel 1). Consequently, prison staff often harbour negative attitudes towards opioid agonist therapy and consider drug dependence to be a social and moral problem that contributes to criminal behaviour, rather than a chronic, recurring illness.40 Despite elevated HIV prevalence within prisons, the legal framework across EECA often falls short of human rights mandates for ensuring access to evidence-based services for addiction and HIV within the criminal justice system. Opioid agonist therapy with methadone or buprenorphine is internationally recognised as the most effective treatment for chronic opioid dependence, and is also among the most effective primary and secondary strategies for HIV prevention available.1,41 Moreover, mathematical modelling suggests that expansion of opioid agonist therapy is the single most cost-effective means to control the HIV epidemic in EECA,42 although when combined with antiretroviral therapy scale-up, is more effective but also more costly.43 Regional policies (tables 1, 2) vary on whether opioid agonist therapy is provided throughout the entire incarceration (Moldova, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan; panel 2), upon entry to police lock-up with supervised withdrawal from opioids (Georgia, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Ukraine), only in the community (Belarus, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan), or not at all (Russia, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan). Moreover, contradictory legal mandates lead to an uneven distribution of care. In Ukraine, although national drug policies necessitate harm reduction programmes (including opioid agonist therapy and needle and syringe programmes) for all people who inject drugs, the medical guidelines require current signs of physical dependence, which are not always evident after a detainee completes withdrawal in police lock-up or in SIZO, disqualifying convicted prisoners from treatment.

Panel 1. Sasha* and the ravages of incarceration.

“Prisons here in Russia are places where people like me go to die. Though arrested often, I went there three times where I watched many people like me die. My first time occurred after police stopped me for a bribe. I had no money so he searched me, found a syringe he said contained heroin, and locked me up. When I got sick from withdrawal symptoms and was most vulnerable, they promised shirka [liquid poppy straw extract] if I admitted to stealing something that I didn’t. I refused, spent a year in SIZO awaiting trial, but was finally convicted for 2 more years because drug users like me don’t stand a chance. I was shocked to learn that drug injection in SIZO and prison was worse than on the streets of Gatchina, where I lived. The guards helped supply drugs and prison leaders made sure we remained addicted. Many of us paid with our lives. Some guys overdosed, others became HIV-infected like me and tuberculosis finished off the rest of us. Even though all of us were sick, seeing a doctor and getting care was nearly impossible. The bosses controlled everything. I swear the doctors were even worse than the guards. They just sent us back to our dorms to die.”

“I was luckier than most and survived my first incarceration. I tried to be strong and avoid drugs. I cut back, but I had money and connections so I still used. I was weak and the prison bosses made sure I could get high and keep their pockets full. Within a week of release, I was back at it again. The police knew it too! They stayed on top of me, extracting their bribes, but once I ran out of money, I was arrested and back in SIZO and prison for another 3 years. This time, they sent me to a colony for seasoned criminals.”

“I developed fevers and lost a lot of weight. I was sure I would die. My family had money and I was able to bribe my way and eventually saw a doctor. Without money, I would have died like everyone else. After 6 months of coughing and 15 pounds lost, my money bought me a fluorogram that was suggestive of tuberculosis, and I was shipped to a specialty tuberculosis colony. It seemed like everyone with tuberculosis also had HIV. I survived the scariest place I had ever been. We were 36 men in a closet with only 12 beds. We stood, coughed on each other, while others slept in shifts. Most guys, including me, would stop or dispose of our tuberculosis medications so that we could get sick and move from our closet to the infirmary where we’d get our own bed. Many who went to the infirmary never left except in a pine box because their medications didn’t work anymore.”

“I must be really strong. As soon as I got out, my parents took me to the local tuberculosis dispensary. Even though I told the doctors about what happened, they didn’t believe me and I went through the entire process again of confirming tuberculosis. I received no medications for several months, developed fevers, drenching night sweats, and weight loss again before they would prescribe medications. I told them the medications had stopped working before, but they started me on the same ones I took before. It was no surprise that medications didn’t work.”

“I got sicker and my parents drove me to St Petersburg to a special hospital, and paid a lot of money for the doctors to find me a bed, prescribe new tuberculosis medications, and for the first time assessed my HIV with a CD4 count. Thankfully, my HIV was not a problem, but they said the tuberculosis might kill me. A doctor from the AIDS Centre said that he would bring me HIV medications if my parents would ‘donate’ some money for the convenience. I remained connected to an intravenous drip for 2 months and received many tuberculosis medications that my parents bought. The tuberculosis and HIV medications began to work. My cough and fevers went away, I gained weight, but I went home taking an entire cup of pills every day for almost 2 years.”

“I know I almost died. Daily, I crave shirka! My mother knows me and never lets me out of her sight. Even when I try to make excuses to get some time alone, she never leaves my side. She knows me. I know me too! One minute alone and I know I will find shirka. If I do, I know I will get another free ticket to prison or to heaven. Either way, I am in prison. I prefer the prison in my house over the one where I know nobody cares.”

Sasha is not his real name.

Panel 2. Candles burning in the night.

Despite its well documented efficacy in both prisons and communities, three countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA)—Russia, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan—legislatively ban any type of opioid agonist therapy, while the remainder provide it in the community. Harsh criminalisation policies that result in high incarceration rates and large numbers of people who use drugs in EECA prisons—compounded by high levels of documented within-prison drug injection in the region—extraordinarily high levels of HIV, viral hepatitis, and tuberculosis and multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) persist. Despite these poor prognostic indicators, a few countries have prevailed over the misaligned ideological policies espoused by Russia that favour punishment over rehabilitation and implemented internationally recognised evidence-based HIV prevention and treatment for prisoners. For example, small and financially vulnerable countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Armenia have introduced all 15 internationally recommended strategies for HIV prevention in prisons,44 including both opioid agonist therapy and needle and syringe programmes. These three countries have emerged as welcomed beacons in the region because they have boldly overcome regional pressures to ban these HIV prevention strategies. Without international funding from international donors, however, such programmes would not exist, even though they remain suboptimally scaled. These successful programmes, however, may soon be jeopardised by anticipated loss of funding from international donors. Moreover, because Russia considers itself a leader in the EECA region and bans both opioid agonist therapies and does not fund needle and syringe exchange programmes, it continues to exert its pressure on other countries within the region by creating new political and trade alliances. By combining their ideological principles to ban HIV prevention programmes within both communities and prisons with financial support through these trade alliances, they could potentially undermine achievements made thus far by some countries in the EECA region that have aligned their HIV prevention strategies with those recommended by the UN based on public health and human rights mandates. It is conservatively estimated that a third of all prisoners in Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, and Armenia are people who use drugs (approximately 6900), mostly of opioids. However, only 802 (12%) individuals are prescribed opioid agonist therapy. Introduction and even scale-up of this therapy is minimally restricted by cost, since methadone is extremely inexpensive. Although its efficacy is well substantiated, policy around opioid agonist therapy is shaped more by ideology and prejudices than by scientific evidence.45,46 Despite these ideological influences in the region, five countries (Armenia, Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, and Estonia) have successfully introduced and expanded opioid agonist therapy throughout their criminal justice systems, including in pre-trial detention (table 2). Recent findings from Moldova, which may be emblematic of prison-based methadone problems in the region, suggest that myths about and prejudices towards opioid agonist therapy are amplified within prisons, resulting in bullying and ostracism of patients potentially undermining expansion efforts.47 In nearby Ukraine, where opioid agonist therapy is not available within prison, extremely negative attitudes toward it prevail among prison personnel, although recent findings40,48 suggest that provision of accurate information and training could partly overcome these myths. The within-prison risk environment is shaped by prisoners who use drugs, those who do not use drugs, prison personnel, and real and enacted policies for the setting; the next generation of efforts to expand opioid agonist therapies will therefore need to address multiple factors, including these myths and prejudices, and the within-prison drug economy, which probably propagates such myths to both incarcerated people who use drugs and to prison personnel who may view it as competition for the illicit drug trade. Continued support for opioid agonist therapy and needle and syringe programmes must therefore not only address service delivery itself, but also include strategies that combat misinformation and prejudices. Continued funding and provision of comprehensive prevention strategies are crucial for sustainability and should be coupled with shared best practices with other EECA countries that seek to align human rights and public health mandates in both community and criminal justice settings.

The confluence of mass incarceration, substance use disorders, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis infections

Mass incarceration

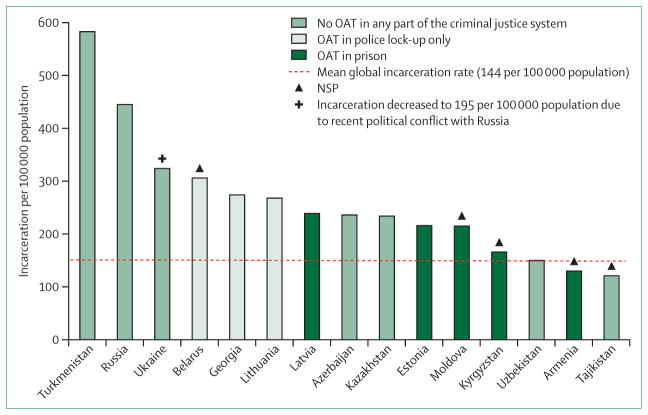

The dramatic rise and inter-relationship between incarceration, HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in EECA is multifactorial.49–52 The Soviet collapse gave rise to many factors that independently and collectively contributed to unprecedented mass incarceration in all EECA, partly as a result of decreasing industrial output, living standards, and life expectancy.4 EECA, with 1.1 million prisoners, has some of the highest incarceration rates globally,11 giving rise to the term “criminological transitions” for EECA countries.53 Although incarceration rates have decreased modestly over the past decade, 13 of the 15 EECA countries still have rates that exceed the world average of 146 prisoners per 100 000 population, with ten exceeding 200: Turkmenistan (583), Russia (455), Belarus (335), Lithuania (315), Georgia (281), Kazakhstan (275), Latvia (264), Azerbaijan (236), Estonia (218), and Moldova (212); Ukraine recently plummeted from 324 to 195 due to regional conflicts.11 This mass incarceration is the result of several intersecting factors, which have converged to result in some of the highest general-population prevalences of HIV,54 hepatitis C virus,55 and tuberculosis (including multidrug-resistant tuberculosis [MDR-TB])12 in the world,49,51 concentrated further within prisons where rates are substantially higher.

Substance use disorders

After 1991, injectable opioid use increased substantially due to changes in drug routes from Afghanistan and the contribution of economic collapse to a new drug economy.8,56 Consequently, volatile opioid injection and HIV epidemics followed.10 Many harsh criminal sanctions towards people who inject drugs ensued, resulting in escalating incarceration rates, especially of those who either had or were at high risk for HIV. Moreover, with the backdrop of economic instability and low wages for public servants such as police, these individuals became targets for bribes and other forms of corruption. Inability to pay resulted in arrest, detention, and imprisonment.57,58 Consequently, people who inject drugs represent more than a third of prisoners in EECA, but the level could be as high as 50–80% in some EECA countries.23,59–61

Explosive dynamics of HIV transmission accompanied the growing rates of injection drug use and incarceration in EECA, with HIV incidence and HIV-related mortality remaining volatile and increasing. Although HIV is concentrated among people who inject drugs and their sexual partners in EECA countries, there is also evidence of transmission among sex workers and men who have sex with men.62 By the end of 2013, there were more than 1.4 million people living with HIV in EECA, with more than 85% of these residing in Russia and Ukraine.63 Despite recent evidence of modestly expanded prevention programmes for HIV in some EECA countries, coverage with antiretroviral therapy (especially among those who inject drugs), opioid agonist therapy, and needle and syringe programmes remains low.5,6 Additionally, extensive migration between and within some EECA countries results in lack of access to HIV prevention on the basis of citizenship or official registration for governmental health care.59,62

HIV infections

Prisons are structural risk environments for transmission of infectious diseases (figure 5) because of the high concentration of people who inject drugs, have HIV, or have hepatitis C virus.54 HIV prevalence in prisoners is high throughout EECA. Although no reliable data exist for Turkmenistan and Belarus, HIV prevalence in prisons exceeds 10% in four countries—Latvia (20.4%), Ukraine (19.4%), Estonia (14.1%), and Kyrgyzstan (10.3%)—and remains markedly higher than in the community in Uzbekistan (4.7%), Lithuania (3.4%), Kazakhstan (3.9%), Azerbaijan (3.7%), Armenia (2.4%), Tajikistan (2.4%), Moldova (2.6%), and Georgia (0.9%). In nationally representative prison surveillance studies, HIV prevalence is 22 times, 19 times, and 34 times higher in prisons than in surrounding communities in Ukraine,23,24 Azerbaijan,59 and Kyrgyzstan,60 respectively. Factors contributing to this increased concentration include harsh policies, laws, and policing targeted at people who inject drugs, and high levels of within-prison drug injection. In Russia, nearly all drug-related convictions are for drug use rather than drug trafficking.64

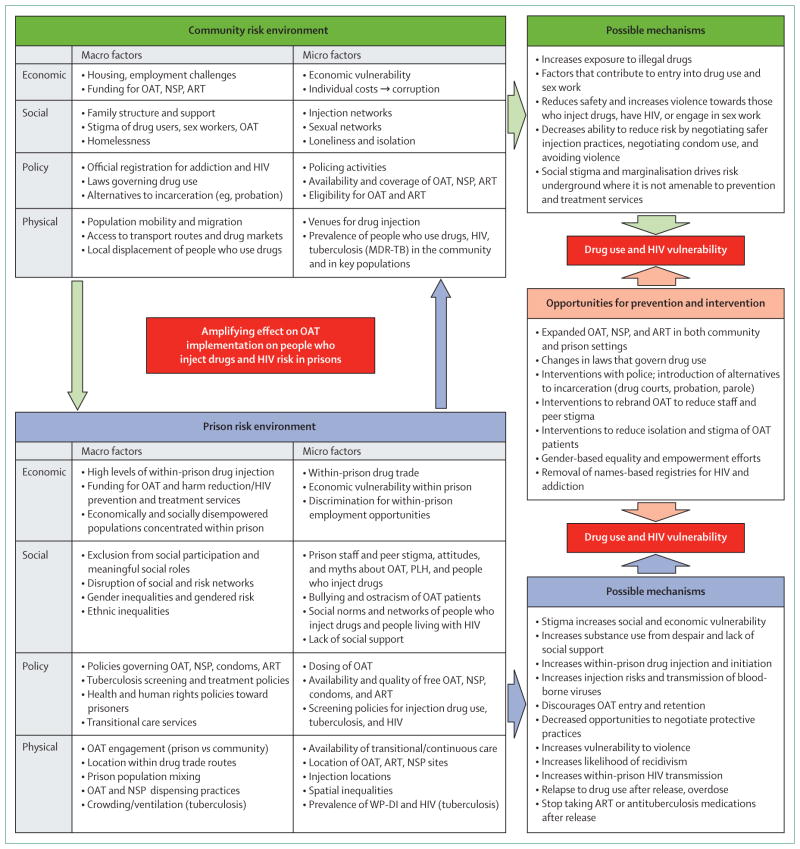

Figure 5. Relationship of the risk environment in community and criminal justice settings in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

OAT=opioid agonist therapy. NSP=needle and syringe programmes. ART=antiretroviral therapy. MDR-TB=multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

Estimates of the prevalence of within-prison drug injection range from 3% to 53%,17,18,65,66 and have contributed to volatile HIV transmission within prisons in the region,67 a sobering consequence of the over-representation of people who inject drugs and have untreated substance use disorders within prison. Evidence suggests that people who inject drugs do so more frequently within the community than they do within prisons, but HIV transmission risks are substantially elevated within prisons because injection equipment is scarce and results in more frequent sharing of contaminated injecting equipment.18 This situation may, in part, contribute to findings that previous incarceration is independently associated with HIV among people who inject drugs in community settings,68 which we also found in our Ukraine case study. Moreover, few studies have examined within-prison drug injection in EECA, but data from HIV-infected Ukrainian prisoners, the only individuals who can transmit HIV, showed extraordinarily high levels of injection drug use within prisons (54%), with many syringe-sharing partners.17

Effective HIV treatment with antiretroviral therapy is an effect method to prevent HIV transmission and must include prisoners,69 many of whom are people who inject drugs.70 Achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets of identifying 90% of people living with HIV, 90% of these initiating and remaining on antiretroviral therapy, and 90% achieving viral suppression, requires more effective HIV screening, treatment, and optimal medication adherence71 in EECA countries, including in prisons. Despite National AIDS Centres in some countries reporting high coverage levels with antiretroviral therapy in prisoners who are diagnosed,61,72 most people living with HIV within EECA prisons remain undiagnosed. Only half of people living with HIV in Ukrainian and Kyrgyz prisons are diagnosed before leaving prison.23,24,60 In Ukraine, fewer than 12% of people living with HIV were aware of having HIV, with another 40% being diagnosed during incarceration, leaving almost half still not aware of their status.24 In Azerbaijan, however, HIV diagnosis approaches 75% of cases.59 Although both Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan provide high coverage of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV who are diagnosed within prison,59,60 fewer than 4% of people living with HIV in Ukrainian prisons receive it.23,24 No EECA country has data for antiretroviral therapy coverage after release, but even data from high-income countries suggest that the transition period from prison is one of heightened vulnerability, when antiretroviral therapy coverage falls precipitously and HIV risk is high,73 especially for women.74,75

Hepatitis C virus infections

One review55 reported hepatitis C virus prevalence among prisoners ranging from 3.1% to 38.0%, with the highest in central Asia.76 Representative prison biosurveillance studies show hepatitis C prevalence to be substantially higher in Ukraine (60.2%),23 Kyrgyzstan (49.7%),60 and Azerbaijan (38.2%),59 even though self-reported lifetime prevalence of injection drug use was substantially lower. These data suggest that drug injection is often under-reported in surveys. Hepatitis C infection in people living with HIV, when left untreated, complicates HIV treatment1 and is associated with accelerated liver fibrosis.77 New direct-acting antiviral treatments are costly, but have low toxicity, short treatment durations, and can cure hepatitis C virus in more than 90% of patients, irrespective of HIV status.78 An internationally funded hepatitis C elimination strategy in Georgia has allowed prisoners to access this treatment, but it is not accessible elsewhere in EECA prisons due to cost constraints.79

Tuberculosis infections

Prisons generally, and especially in EECA, promote tuberculosis transmission (particularly drug-resistant strains), primarily because of crowding that increases contact between large numbers of high-risk individuals in poorly ventilated facilities over extended periods.12,13 Furthermore, tuberculosis control is complicated by low cure rates due to delayed diagnosis, ineffective control policies (ie, screening, isolation, and treatment) in prisons, and perverse environmental disincentives to start or continue treatment (eg, better housing, treatment, or food, being excused from harsh work, and profiting from the sale of tuberculosis medications; panel 1).80–82 Incarcerated individuals often have risk factors which increase their susceptibility to tuberculosis (eg, poverty, substance use disorders, homelessness, malnutrition, and HIV infection) and are often released to the community before treatment completion, without effective transitional care.12,83–85

Factors contributing to tuberculosis transmission include overcrowding, high prisoner turnover, limited access to health-care services, delayed case detection and poor contact detection, lack of recommended rapid diagnostic methods such as Xpert MTB/RIF, and suboptimal treatment of infectious cases and implementation of tuberculosis infection control measures.83–85 MDR-TB is disproportionately prevalent in EECA prisons86,87 because of high prevalence in the community88–91 and large numbers of HIV-infected people who inject drugs (who are more susceptible to tuberculosis due to being immunocompromised), and low treatment completion rates for tuberculosis.92 The Ukraine case study illustrates the large degree to which incarceration contributes to tuberculosis transmission in EECA, with tuberculosis incidence rates directly correlated with increasing mass incarceration.12 Additionally, MDR-TB incidence in EECA after independence was directly correlated with increasing mass incarceration.12

The Soviet Union collapse resulted in inadequate funding and supply of first-line tuberculosis regimens and extended confinement that facilitated transmission within prisons.93 In Belarus, MDR-TB strains represent 35.3% of new and 76.5% of previously treated tuberculosis cases, meaning that half of all tuberculosis cases are MDR-TB.87,94 Incarceration and HIV are independent contributors to the risk of patients having MDR-TB strains.87 Remarkably high levels of MDR-TB also exist in Russia,95,96 Lithuania and Latvia,96 and Ukraine.97 International guidance for tuberculosis screening and treatment98 is inconsistently deployed in prisons throughout EECA, with resultant poor outcomes.83,85 One notable exception is Azerbaijan, which reduced both tuberculosis and MDR-TB cases through the effective implementation of the WHO’s Stop TB Strategy in the penitentiary sector, which involved routine screening, specialty tuberculosis hospitals, new infection control measures, rapid diagnostic testing, and training of prison personnel who now train prison staff elsewhere in EECA.36

Case study: evaluating the impact of HIV and tuberculosis transmission in Ukraine—a country in conflict

Ukraine, a middle-income country of 45 million people, is in the midst of conflict and has the highest prevalence of HIV in adults among EECA countries (1.2%), with tuberculosis and MDR-TB contributing the most to HIV-related mortality.3 Before Russia’s invasion of Crimea and the Donbas region, Ukraine’s incarceration rate per 100 000 population was 324, but recently dropped to 195 per 100 000 in 2014 with large numbers of prisoners rapidly released to the community, increasing numbers of arrests and initiation of a new probation system that now supervises 70 000 people in the community. Incarceration among people who inject drugs in national surveys, however, does not appear to have decreased from 2011 to 2015.99,100 HIV prevention services in Ukraine are under-scaled with only 2.7% of 310 000 people who inject drugs prescribed opioid agonist therapy and only 20% of people living with HIV prescribed antiretroviral therapy. Globally and within EECA, people who inject drugs experience high levels of incarceration (lifetime: 40–85%),101,102 and current or previous incarceration is associated with heightened injecting risks and increased transmission of HIV and hepatitis C virus.103–105 In Ukraine, at least 52% of people who inject drugs have been incarcerated,25,26,106 with previously incarcerated people who inject drugs reporting an average of five incarcerations, each a year in duration.23,25,26

Data from three recent national surveys among people who inject drugs25,26 and current prisoners23 in Ukraine were used for the epidemiological analyses and HIV transmission modelling, described briefly in boxes 1 and 2 and further in the appendix. These data suggest that previously incarcerated people who inject drugs have a significantly higher HIV prevalence than never-incarcerated people who inject drugs (28% vs 13%; appendix figure p 25), even after controlling for injecting duration (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.8, 95% CI 1.6–2.1). Additionally, they have heightened HIV risk behaviours, with previously incarcerated people who inject drugs reporting 3.9 (95% CI 2.8–5.0) more injections per month,26 and a 1.5 times (95% CI 1.3–1.9) greater chance of sharing syringes26 than never-incarcerated people who inject drugs, even after controlling for injecting duration. Recently released people who inject drugs (in the past year) had an even greater likelihood of syringe sharing (aOR 2.2, 95% CI 1.6–3.0).26 Similarly, currently incarcerated people who inject drugs have more than twice the HIV prevalence of never-incarcerated people who inject drugs (28.5% vs 12.8%)23,24,26 and high rates of syringe sharing.17,57 Together, these data suggest that incarceration and the post-release period are important contributors to HIV transmission among people who inject drugs in Ukraine and forms the basis for our HIV modelling (box 1). This modelling suggests that incarceration, and specifically the heightened injecting risks after incarceration, could contribute 55% of new HIV infections among people who inject drugs in Ukraine over the next 15 years if we assume all this elevated risk is attributable to incarceration, or 28% if we conservatively assume that only the heightened risk among recently released people who inject drugs is due to incarceration. Conversely, reduced incarceration of people who inject drugs is unlikely to substantially decrease new HIV infections over the 15-year period because of the remaining elevated risk among previously incarcerated people who inject drugs. Scaling up and continuing prison-based opioid agonist therapy after release, however, could avert 19.8% of HIV infections over 15 years because it directly reduces the heightened post-release risk (figures 1, 2).

Figure 1. Projected HIV trends among people who inject drugs in Ukraine.

Figure shows projected median trends for people who inject drugs. (A) HIV prevalence among individuals in the community (both never-incarcerated and previously incarcerated). (B) HIV prevalence among incarcerated individuals. (C) HIV incidence among individuals in the community (both never-incarcerated and previously incarcerated). (D) HIV incidence among incarcerated individuals. Scenarios shown are for the status quo, and if there was either: no effect of incarceration on transmission risk after 2015; no further incarceration after 2015; or initiation of opioid agonist therapy in prisons with 50% coverage among incarcerated people who have ever injected drugs who are maintained on therapy for a year after release. Data points with 95% CIs are shown for comparison and shading represents the 95% credibility intervals for the status quo projection (light blue shading) and if incarceration had no effect on transmission risk after 2015 (pink shading).

Figure 2. Prevention of new HIV infections.

Figure shows percentage of new HIV infections that would be averted over 15 years (from 2015 and 2030) under the following scenarios: if incarceration no longer elevated transmission risk (full and conservative projections); if there was no further new incarceration of people who inject drugs; or if prison opioid agonist therapy was scaled up with or without retention after release. Bars show the median projections, while error bars show the 95% credibility intervals. Text above the error bars are the median projections and the corresponding 95% credibility interval. OAT=opioid agonist therapy.

Tuberculosis incidence across EECA is high (nearly all more than 100 per 100 000 population), and is positively correlated with country-level incarceration rates,12 highlighting the importance of within-prison tuberculosis transmission to the countrywide epidemics. An ecological analysis12 estimated that across EECA, each percentage point increase in a country’s incarceration rate corresponded to a 0.34% increase in tuberculosis incidence (95% CI 0.10–0.58). Findings from a systematic review33 suggested that tuberculosis incidence in low-income and middle-income countries is ten to more than 30 times greater within prison than in the community. Few studies, however, have estimated the contribution of incarceration to the tuberculosis epidemic in EECA, with the systematic review estimating that between 5% and 17% of tuberculosis cases in Russia could be due to exposure within prison.33 We therefore conducted in-depth statistical analyses with the datasets used for the HIV modelling23,25,26 to evaluate the role of incarceration for increasing tuberculosis disease risk among the general population and in people who inject drugs in Ukraine (box 2). These analyses suggest that incarceration is an important contributor to tuberculosis transmission (figure 3), and could be responsible for three-quarters of new yearly tuberculosis infections among people who inject drugs and 6.2% of all yearly tuberculosis infections in Ukraine.

Figure 3. Association between number of years incarcerated and prevalence of ever having tuberculosis among prisoners (A) and people who inject drugs in the community (B) in Ukraine.

The points are the mean proportion of prisoners or people who inject drugs in the community reporting ever having tuberculosis for different reported years in prison; the error bars are 95% bootstrapped CIs about the mean. The solid green line is the best logistic fit to the data, and the green shaded area is bounded by the best logistic fits to the lower and upper confidence bounds of the data. Data for prisoners are derived from a 2011 PUHLSE national prison survey.23,24 Data for those in the community are derived from a multi-site ExMAT survey of people who inject drugs in Ukraine in 2015.25

Risk environment framework for criminal justice settings in the region

Overview

Figure 5 provides an overview of the risk environment factors in both the community and criminal justice system that contribute to onward disease transmission in EECA. The high prevalence of these infections in the community, coupled with both micro-level and macro-level factors embedded within the physical, social, economic, and policy and legal framework, result in the concentration of high-risk key populations such as those who inject drugs and sex workers in the criminal justice system. Incarceration, a physical factor, further amplifies these conditions by concentrating individuals with these infections. It also disrupts injection and social networks, a social factor, by creating new and riskier networks that develop as a survival tactic during incarceration.107 HIV prevalence in Ukrainian prisons is high (19.4%),23 but policy factors forbidding opioid agonist therapy or needle and syringe programmes, poor HIV detection, and low antiretroviral therapy coverage24 facilitate frequent sharing of injecting equipment17 and probably fuel HIV and hepatitis C virus transmission.17,23,24,60 Similarly, individuals released from prison are highly stigmatised (social factor), relapse to drug use quickly (policy factor), develop new injection networks (social factor), and policing efforts target people who inject drugs and former prisoners due to registration of people who inject drugs in the community (policy factor).57 Our analyses from our Ukraine case study suggest that the prison risk environment contributes to both HIV and tuberculosis transmission in people who inject drugs and tuberculosis transmission more generally to the community. Moreover, our findings suggest that introducing opioid agonist therapy to 50% of people who inject drugs within prison and retaining them in treatment for 12 months post-release would be the most effective strategy to reduce HIV incidence over the next 15 years, suggesting that this risk environment can be greatly influenced by the introduction of evidence-based addiction treatment with continuity into the community after release.

Drug-related policies

Key populations face many legal barriers that simultaneously contribute to incarceration and access to essential HIV programmes and services.108,109 Drug policies vary considerably. In seven EECA countries (Russia, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Lithuania, and Latvia) official names-based registration of people who inject drugs is required to receive treatment, including opioid agonist therapy. Registration, however, often results in restrictions in employment, loss of privileges (eg, driver’s licence), and targeting by police.57,110–112 Moreover, a passport and an official address is required for employment in Ukraine, undermining economic stability.111 Collectively, these restrictions perpetuate re-incarceration,113 especially given that alternatives to incarceration are uncommon in any EECA country. Addiction experts are required to report anyone accessing services, including for diagnosis confirmation, registration, and treatment. In most registries, there is little guidance or criteria to remove names from the registry or to define recovery from addiction. In Moldova and Uzbekistan, people who inject drugs are monitored for 3 years before removal from the registry is considered. In Uzbekistan, removal from the registry occurs upon incarceration. Otherwise, name-based registries persist for life.

Six countries have a mix of administrative and criminal penalties for drug possession. In Kazakhstan, administrative procedures can be deployed twice annually for drug possession, after which arrest and criminal sanctions ensue. In Kyrgyzstan, these penalties differ based on the quantity of illicit drugs found. Elsewhere, administrative procedures are used for individuals caught in possession of limited amounts for personal use, although the amount varies. In all countries, the criminal code defines the purchase of illicit drugs as an incarcerable criminal offence.

Punitive drug laws restrict access to HIV testing and treatment for people who inject drugs. Criminalisation of drug use and discriminatory practices restrict access to needle and syringe programmes and community agencies where these services are located. Harm reduction services are often legally restricted to adults. Police in some countries arrest people who inject drugs who access harm reduction services and confiscate drugs and syringes, or extract bribes for the possession of syringes or needles.57,58,114,115 In one Russian survey of people who inject drugs, more than 60% had been arrested for needle possession or had drugs planted on them by the police.116

Sexual activity policies

Although many EECA countries have repealed laws prohibiting same-sex relationships, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan continue to enforce them. Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, and Armenia have laws that criminalise sex acts between consenting adults of the same gender, sodomy, and cross-dressing or gender impersonation. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have legislation where the age of consent differs for homosexual and heterosexual sex; Kyrgyzstan has laws or policing practices criminalising or preventing condom distribution yet supplies them within prison. Although transparent in its intent to target and stigmatise men who have sex with men, Russia’s legislation prohibiting dissemination of “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations [ie, LGBT] among minors” is ostensibly to protect so-called traditional family values. These laws result in arrest of individuals promoting HIV prevention for men who have sex with men. Similar but harsher legislation is being considered in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.62

All EECA countries prohibit sex work, but police enforce it variably and especially target sex workers who use drugs. Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, and Uzbekistan have laws or policies allowing mandatory HIV testing of key populations. Some countries (Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, and Armenia) have laws that protect against human rights violations, but they are not specific to HIV or key populations.

Community supervision

Community sanctions such as probation or drug courts are not widely available, and probation is not generally linked to treatment. Several countries have limited community-based supervision, including Russia (supervision by former military or prison personnel), Ukraine (new in 2015), Moldova (started 2002), Latvia (started in 2005), Estonia (started in 1998 with expansion in 2013), Lithuania, Georgia, and Kazakhstan. Pilot projects are underway in Armenia to guide probation service initiation. Some probation programmes refer cases to drug treatment agencies or psychiatric hospitals. Many of the probation programmes emerged from the prison service and therefore reflect the prison culture. In most instances, probation is in its infancy.

Coverage with opioid agonist therapies

Many prisoners in EECA not only initiate drug injection within prison, but continue to share injecting equipment during incarceration17,60 and especially after release.17 Five countries (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Latvia, and Estonia) have opioid agonist therapy in prisons, with coverage being extremely low. Georgia has a pilot programme in SIZO and four others offer it only in police lock-up (table 1, figure 6). Emblematic of the region, Ukraine’s prison personnel have especially negative attitudes towards opioid agonist therapy, although this is improved when they are sufficiently knowledgeable about its benefits;40 prisoners, meanwhile, often have high expectations about recovery that diminish after release in the absence of opioid agonist therapy.48 In Moldova, opioid agonist therapy and needle and syringe programmes exist within communities and prisons, but treatment coverage is disproportionately lower in the community than in prisons, reducing access after release and necessitating many patients to discontinue therapy before release. In Moldova, prisoners receiving opioid agonist therapy are often ostracised by other prisoners, perhaps due to illicit drug economies within prisons that compete with opioid agonist therapy.40,47 Thus, effective and essential scale-up of opioid agonist therapies must coincide with education and motivation of both prisoners and prison personnel.

Figure 6. Incarceration in EECA countries and availability of opioid agonist therapies and needle and syringe programmes.

EECA=Eastern Europe and Central Asia. OAT=opioid agonist therapy. NSP=needle and syringe programme.

HIV diagnosis

The first step to achieving the UNAIDS 90-90-90 strategy is HIV testing.71 Most EECA prisons deploy risk-based opt-in testing within prisons. One of the major challenges in EECA prisons is low HIV detection; more than half of HIV-infected prisoners do not know their HIV status.23,24,60,61 For those that do, however, most are tested within prison.23,24,59,60 Notable exceptions in which expanded HIV testing has greatly improved HIV diagnosis include Estonia117 and Azerbaijan.59 Required name-based HIV registries often undermine voluntary testing efforts and treatment engagement.98,108 Officially reported HIV data therefore underestimate true prevalence,118 with restriction of access to HIV treatment due to mandatory registration combined with stigma, discrimination, and criminalisation of key populations.6,110,119 Similarly, patients receiving opioid agonist therapy must be officially registered before receiving it in all EECA countries, which can lead to restrictions on employment opportunities, limitations in housing, and revocation of drivers’ licences, further compounding economic disparities.119

Conclusions

The 1990 United Nations Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners state that prisoners “shall have access to the health services available in the country without discrimination on the grounds of their legal situation”.120 This basic principle has been expanded in the case of HIV to also include preventive services, but has been infrequently applied, especially in many EECA countries where prisoners derive less benefit from prevention and treatment services than other citizens.121 Structural aspects of the criminal justice system in EECA concentrate most at-risk populations, which, taken together, probably contribute heavily to disease amplification and transmission within prison and to the community after release. These structural impediments also limit access to prevention and treatment services for HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis. Our findings suggest that the high-risk prison environment, including the immediate period after release (for HIV), is an important contributor to HIV and tuberculosis transmission in people who inject drugs and more broadly for tuberculosis transmission in the general population. Strategies that reduce incarceration overall (especially for people who inject drugs) and greatly expand the availability of opioid agonist therapy within prison, ensuring effective continuation of this therapy after release, will probably have the greatest impact on HIV and tuberculosis transmission in people who inject drugs interfacing with the criminal justice system. Strategies that reduce incarceration for the entire population, but especially for people who inject drugs, are also likely to reduce tuberculosis cases. Not only are policy reforms necessary to abrogate this trajectory, but further epidemiological, qualitative, modelling, cost-effectiveness, and implementation science research are crucial to help ensure that both prisoner and public health are optimised and consistent with human rights mandates (panel 3). Such approaches could reduce the transmission of HIV, hepatitis C virus, and tuberculosis in these settings, especially if they also ensure continuity of care after release from prison.

Panel 3. Recommendations for prevention and treatment policies.

Develop strategies to reduce incarceration rates in key populations

Laws and policies that criminalise personal drug use and sex work should be changed. New strategies should be developed that directly aim to reduce incarceration, especially to address tuberculosis transmission in people who use drugs. Modelling and statistical analyses here confirm the negative contributions of incarceration, especially on people who inject drugs, on perpetuating the HIV and tuberculosis epidemics. For example, current policing policies target high-risk individuals (ie, people who use drugs, registered drug users, sex workers, etc) and few provide community policing that focuses on engagement of drug users in evidence-based treatment for addition or harm reduction services in the community. Development of community policing efforts, pre-booking diversion programmes, alternatives to incarceration such as drug courts, or community supervision in probation that favours rehabilitation and treatment over incarceration are needed. Quality community supervision in probation that engages people living with or at risk for HIV in community settings where supportive social networks remain, and prevention and treatment is uninterrupted, is crucial.

Improve HIV testing and treatment strategies

In order to meet UNAIDS policies for 90% detection, coverage of antiretrovirals, and viral suppression (90-90-90), prisons in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) must improve HIV testing strategies because HIV identification falls far lower than UNAIDS targets. Although some countries meet mandates for antiretroviral therapy coverage, room for improvement remains. Identifying HIV and increasing antiretroviral therapy coverage within prisons must, however, be linked to continuity of therapy after release, including linkage to opioid agonist therapy.

Reduce gap between prison and community health-care services

Prisoners with comorbid conditions have a right to the same standard of prevention and treatment services as those in community settings.122 Substance use disorders should be addressed as chronic, recurring health conditions, and should be screened for and treated in accordance with the UN Mandela Rules that support similar standards in both prisons and the community. Opioid agonist therapy programmes are substantially less expensive than imprisonment; modelling findings suggest that the most effective strategy to reduce HIV transition is to increase coverage of opioid agonist therapy to people who use drugs within prison and effectively transition them to opioid agonist therapy after release. When international donors fund HIV treatment and prevention (eg, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief), these agencies should stipulate that such prison-based programmes are both introduced and scaled-to-need as part of a national strategy as a requirement for continued funding.

Introduce and expand opioid agonist therapy, needle and syringe programmes, and antiretroviral therapy in the criminal justice system