Device-related infections with this pathogen frequently require prolonged parenteral therapy.

Keywords: Corynebacterium striatum, bacteria, antimicrobial resistance, multidrug resistance, parenteral antimicrobial drugs

Abstract

Corynebacterium striatum is an emerging multidrug-resistant bacteria. We retrospectively identified 179 isolates in a clinical database. Clinical relevance, in vitro susceptibility, and length of parenteral antimicrobial drug use were obtained from patient records. For patients with hardware- or device-associated infections, those with C. striatum infections were matched with patients infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci for case–control analysis. A total of 87 (71%) of 121 isolates were resistant to all oral antimicrobial drugs tested, including penicillin, tetracycline, clindamycin, erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin. When isolated from hardware or devices, C. striatum was pathogenic in 38 (87%) of 44 cases. Patients with hardware-associated C. striatum infections received parenteral antimicrobial drugs longer than patients with hardware-associated coagulase-negative staphylococci infections (mean ± SD 69 ± 5 days vs. 25 ± 4 days; p<0.001). C. striatum commonly shows resistance to antimicrobial drugs with oral bioavailability and is associated with increased use of parenteral antimicrobial drugs.

Corynebacteria are a normal component of the microbiota of human skin and mucous membranes. At the University of Washington Medical Center (Seattle, WA, USA), Corynebacterium striatum has historically been the second most commonly isolated Corynebacterium species, after C. jeikium (1). Although C. striatum is a frequent colonizer (2), it might also be implicated as a true pathogen when isolated in multiple samples from sterile sites or from indwelling hardware and devices (2–9). Determination of whether an isolate represents infection, colonization, or contamination is based upon clinical judgment.

Although early reports indicated that C. striatum isolates were frequently susceptible to many antimicrobial drugs, including β-lactams, tetracycline, and fluoroquinolones (8–11), more recent studies have demonstrated increasing multidrug resistance (12–17). To clarify the spectrum of disease associated with C. striatum, we retrospectively extracted clinical information for immunocompetent patients with C. striatum isolates to determine clinical relevance, antimicrobial drug susceptibilities, and length of parenteral therapy. For patients with device-associated infections, we compared the length of parenteral therapy for C. striatum with that for coagulase-negative staphylococci, other low-virulence organisms that commonly colonize the skin.

Methods

Patients

We used an algorithm-based query of the De-Identified Clinical Data Repository maintained by the Institute for Translational Health Sciences of the University of Washington (Seattle, WA, USA) to identify 213 patients from the university medical center infected with C. striatum isolated from a clinical sample during 2005–2014. Adult patients (>18 years of age) were included if C. striatum was isolated from a specimen submitted for bacterial culture and identified to the species level. Because we were interested in whether C. striatum would be considered pathogenic in an immunocompetent population, patients with active immunosuppression were excluded from our analysis. We excluded 34 patients with immunosuppressant use at the time of culture with microbiological growth on the basis of pharmacy records (defined as documentation of use of corticosteroids, methotrexate, infliximab, adalimumab, tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, or rituximab), or with a diagnosis of active malignancy or HIV/AIDS according to codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision. Our algorithm-based method was confirmed by using a manual chart review.

Bacterial Identification and In Vitro Drug Susceptibility Testing

Corynebacteria were identified to the species level if isolated in pure culture or if deemed to be clinically meaningful if present in a polymicrobial culture. Identification of corynebacteria was initially performed during 2005–2012 by using the RapID CB Plus Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). This kit correctly identifies 95% of Corynebacterium isolates to the species level (18). During 2012–2014, corynebacteria were identified by using matrix- assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MALDI Biotyper and Biotyper software versions 3.0 and 3.1; Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) and a cutoff score of 2.0. Use of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with the Bruker system database correctly identifies corynebacteria to the genus level for >99% of isolates and correctly identified C. striatum in 100% (51/51) of clinical isolates tested (19).

Phenotypic susceptibility testing was performed by using the E-test (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Étoile, France) and Remel blood Mueller Hinton agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubation for 24–48 h at 35°C in ambient air, according to breakpoints of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (20). Because breakpoints have recently changed (21), we tested whether shifting the breakpoint would alter our results. Susceptibilities were available for penicillin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline. For patients from whom >1 isolate of C. striatum were obtained, we considered only the first isolate in our analysis.

Clinical Data Extraction

We obtained the following variables from chart review by manual extraction: patient location when the culture was obtained (i.e., inpatient versus outpatient), whether the culture grew C. striatum in pure culture or was polymicrobial, whether the treating physician considered the isolate to be clinically relevant or a contaminant, length of parenteral therapy administered, and whether adverse events were documented. If the treating physician did not comment on the isolate, the isolate was categorized as clinically irrelevant. Adverse events were defined as clinical event necessitating a change in antimicrobial agent and were graded according to the Common Terminology for Adverse Events (22). Serious adverse events were considered grade 3 or 4. The outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy practices at the University of Washington Medical Center monitor for adverse events by weekly measurement of a complete blood count and monitoring of renal function. We used these weekly measurements as a proxy to verify ongoing administration of outpatient parenteral therapy in combination with review of documentation in clinical notes.

Matched Case−Control Analysis

In a subset of patients with hardware-associated osteomyelitis or infections of implanted cardiac devices, we performed a matched case−control analysis to examine length of parenteral therapy in C. striatum cases compared with that for persons infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci (controls). Persons infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci were chosen as controls because isolates are frequently found in clinical samples (enabling appropriate matching), colonize the skin, and generally have low virulence, similar to C. striatum. Cases were matched to controls on the basis of age (± 5 years), site of infection, and presence or absence of hardware associated with the infection site.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are reported as mean ± SE. Parametric data were compared by using the t-test, and nonparametric data were compared by using χ2 or Mann-Whitney U tests. A p value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We identified 179 immunocompetent adult patients infected with C. striatum isolated from clinical specimens. A substantial proportion (48%, 86/179) of these isolates were believed to be from clinically relevant infections. For comparison, in our laboratory system during a similar period, ≈42,000 isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and 4,800 isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci were recovered with in vitro susceptibilities determined.

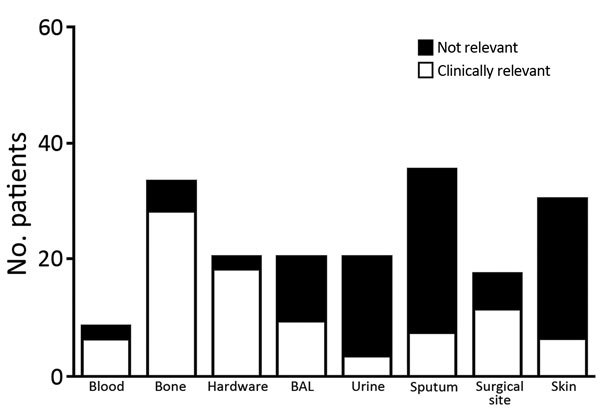

Consistent with previous reports that C. striatum is a colonizer of the skin and mucous membranes, isolates were frequently reported in sputum and skin samples (65/179) (Figure 1). Interpretation of clinical relevance varied markedly by sample site. Isolates from deep surgical specimens, such as bone and surgical hardware, were generally considered to be clinically relevant (88%–95%), whereas isolates from urine, sputum, or skin were rarely considered to be clinically relevant (10%–15%) (Figure 1). Isolates from bronchoalveolar lavage samples were indicated by clinicians to be clinically relevant in 45% (9/20) of cases, and all of these patients were empirically treated with vancomycin for healthcare-associated pneumonia for a mean ± SE duration of 11 ± 1.9 days. No clinical failures for vancomycin therapy were documented.

Figure 1.

Patients infected with Corynebacterium striatum, by specimens isolated from a particular anatomic site, at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA, 2005–2014. Hardware, surgical specimen obtained from a location anatomically in connection with a foreign device; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; urine, specimen isolated from a urine sample (we were unable to determine presence or absence of a catheter); surgical site, deep surgical specimen; skin, wound swab from a nonsurgical superficial specimen.

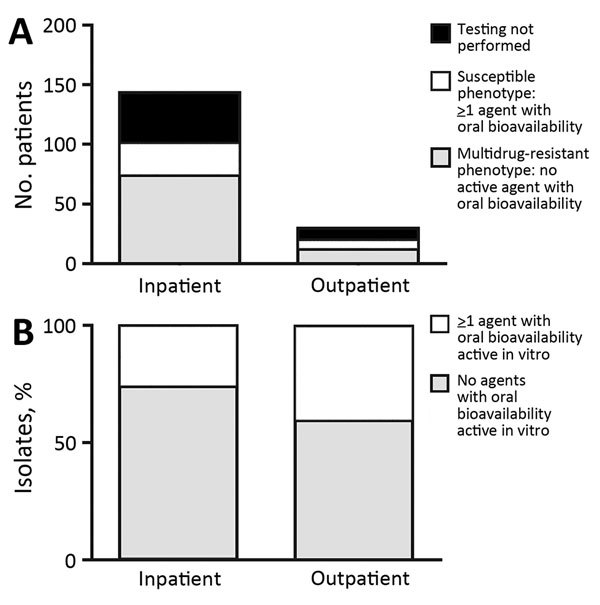

Eighty percent (143/179) of isolates were found in an inpatient setting. Susceptibility testing was performed for 121/179 isolates, and 72% (87/121) were resistant to all oral antimicrobial drugs tested (Figure 2). The percentage of drug-resistant isolates obtained from the inpatient setting did not differ from that found in the outpatient setting (p = 0.27).

Figure 2.

Numbers (A) and percentages (B) of Corynebacterium striatum isolates from patients at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA, 2005–2014, with a multidrug-resistant phenotype for all antimicrobial drugs tested (penicillin, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline). Inpatient or outpatient indicates clinical setting in which cultures were performed.

We determined in vitro susceptibilities for several antimicrobial drugs (Table). In general, MIC distributions were bimodal, whereby most drugs had low MICs or high MICs, except for vancomycin, which was universally active in vitro. The breakpoint of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute for penicillin changed in 2015 (21) from 1 mg/L to 0.125 mg/L. This change increased the rate of isolates considered penicillin resistant from 85% to 98%, but did not affect the number of isolates without an oral drug option because all isolates with a penicillin MIC <1.0 mg/L were susceptible to tetracycline. Daptomycin was rarely formally tested in our laboratory during this period (n = 6), including the 2 patients we previously described (14). Initial MICs for daptomycin were 0.032–0.125 mg/L, but it was rarely used by clinicians in our cohort. Similarly, linezolid was rarely tested (n = 10), was uniformly active in vitro, but was not used clinically.

Table. Drug resistance patterns for Corynebacterium striatum isolates from patients at the University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA, 2005–2014*.

| Characteristic | Penicillin, n = 121 | Tetracycline, n = 119 | Clindamycin, n = 103 | Erythromycin, n = 72 | Ciprofloxacin, n = 119 | Vancomycin, n = 120 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean MIC | 18 | 34 | 209 | 66 | 51 | 0.6 |

| Median MIC | 8 | 32 | 256 | 16 | 32 | 0.5 |

| MIC range | 0.125–256 | 0.125–256 | 0.25–256 | 0.25–256 | 0.125–256 | 0.125–1 |

| MIC50 | 8 | 32 | 256 | 16 | 32 | 0.5 |

| MIC90 | 32 | 64 | 256 | 256 | 32 | 1 |

*Resistance is defined as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Guidelines (20). Values are in milligrams/liter. MIC50, concentration required to inhibit 50% of bacteria; MIC90, concentration required to inhibit 90% of bacteria.

All patients with infections deemed to be clinically relevant were initially given vancomycin, except 1 patient with a documented allergy to vancomycin who received daptomycin. As expected, the length of time parenteral antimicrobial drugs were administered varied widely by anatomic site of infection and presence of a foreign body. Prosthetic joint infections were treated with parenteral therapy for 54 ± 7 days, and other hardware- or device-associated infections were treated for 65 ± 10 days. One patient with a ventricular assist device−associated infection who received vancomycin for 650 days was excluded from this analysis (outlier).

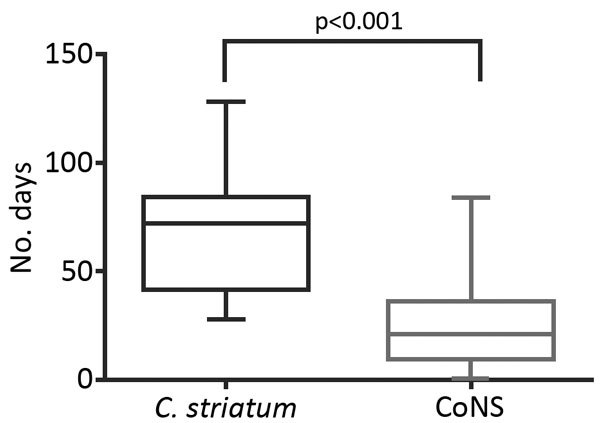

In a subset restricted to the 38 patients with hardware (including prosthetic joint) or device-associated infections deemed clinically meaningful, we successfully matched 27 patients with control patients infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci. Eleven patients could not be matched for site of infection or age. When we compared control patients infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci with patients infected with C. striatum, we found that those infected with C. striatum had a longer course of parenteral antimicrobial drugs (69 ± 5 days vs. 25 ± 4 days; p<0.001) (Figure 3). C. striatum isolates were more likely to be monomicrobial (14/27, 52%) than coagulase-negative staphylococci (5/27, 19%) (p = 0.02).

Figure 3.

Length of use of parenteral intravenous antimicrobial drugs in matched case−control analysis of Corynebacterium striatum isolates and isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci in patients with hardware-associated infections, University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle, Washington, USA, 2005–2014. Horizontal lines within boxes indicate median values, whiskers indicate minimum and maximum values, and boxes indicate 25th and 75th percentiles. Mean durations of parenteral antimicrobial drug use for patients infected with C. striatum and those infected with coagulase-negative staphylococci were compared by using the Mann-Whitney U test. CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci.

Five serious adverse events were associated with parenteral antimicrobial drugs in the C. striatum group and only 1 serious adverse event in the coagulase-negative staphylococci group (p = 0.19). The serious adverse events (all associated with vancomycin) were 1 drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome, 2 acute kidney injuries with creatinine levels >3 times baseline values, and 3 absolute neutrophil counts <1,000 cells/mm3.

Discussion

Because C. striatum can be a component of the skin microbiota, determination of whether microbiologic growth in a clinical sample represents an infection depends on clinical judgment. Previous investigations have described C. striatum primarily as a nosocomial pathogen, frequently in the setting of underlying malignancy or organ transplantation (15,23,24). Our report documents that clinicians encountering C. striatum in clinical samples of immunocompetent patients frequently consider the isolate to be a true pathogen.

Prior studies of small groups of patients have indicated that isolation of C. striatum from bone or a medical device is typically considered by the treating physician to be relevant (24–26), and our study confirms these findings. Furthermore, our study provides support for the pathogenic role of C. striatum in hardware-associated infections because we found that these infections with C. striatum were more likely to be monomicrobial than infections with coagulase-negative staphylococci. In contrast to some reports in which isolation from a respiratory sample was frequently determined to be clinically relevant (15,27,28), less than half of the respiratory isolates in our study were considered to reflect lower respiratory tract infections.

We documented that a multidrug-resistant phenotype of C. striatum directly affects clinical care. Osteomyelitis and hardware-associated infections are difficult to treat, often requiring a prolonged course of antimicrobial drugs. In some situations, guidelines recommend a limited duration of parenteral therapy followed by a longer period of oral therapy (29). A lack of well-tolerated oral treatment options active against C. striatum would be expected to lead to a longer duration of use of parenteral antimicrobial drugs for patients with these infections, and our matched case−control study confirmed this expectation.

The longer that parenteral antimicrobial therapy is necessary, the greater the likelihood of adverse events associated with intravenous access. These events include a rate of line events (mostly thrombosis) ranging from 5 to 17 episodes/100 devices and infection rates of 0.5 to 5 infections/100 lines (30). Although we documented more adverse events associated with treatment in the C. striatum group than in the coagulase-negative staphylococci group, this difference did not achieve a priori statistical significance, and we did not capture line thrombosis events. Furthermore, parenteral therapy is associated with substantially increased costs, even when comparing an inexpensive parenteral antimicrobial drug (vancomycin) with an expensive oral antimicrobial drug (linezolid) (31). In addition, parenteral options for C. striatum will be increasingly limited because our group and others have reported clinical failures caused by rapid development of high-level daptomycin resistance (14,16,25). Because daptomycin resistance can emerge rapidly, it is reasonable to assume that increased daptomycin use could also cause resistance to this drug.

One oral treatment option for multidrug-resistant C. striatum infections is linezolid. Although testing for C. striatum linezolid susceptibility is rarely performed in our clinical microbiology laboratory, to our knowledge, linezolid resistance has never been reported for corynebacteria. Nevertheless, linezolid is poorly tolerated during the long courses of treatment required for hardware- or device-associated infections and has shown a rate of adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation ranging from 34% to 80% (32,33). None of our patients in our study were treated with linezolid for a prolonged time, which most likely reflects reluctance of physicians to use an agent with such a high rate of toxicity.

We demonstrated that multidrug resistance was common even in isolates that were not considered to be clinically meaningful in an outpatient setting. We hypothesize that these resistant strains of C. striatum are probably circulating in the community rather than emerging under nosocomial pressure, but further studies would be needed to establish the ecologic niche of drug-resistant C. striatum strains.

Strengths of our study include a systems-wide approach to C. striatum infections in immunocompetent hosts and the large number of C. striatum case reports we reviewed. Detailed clinical information, including the treating physician’s interpretation of the sample, was linked to microbiological isolates. C. striatum will probably be recognized in more clinical settings because use of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry enables C. striatum to be rapidly identified to the species level with a high degree of confidence without molecular techniques (19).

Limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and use of data from 1 health system, which restricted potential generalizability of the results. Given that our study was a retrospective study conducted over a 10-year period, we also cannot state whether the isolates are clonally related or reflect a diverse group with divergent mechanisms of drug resistance. In addition, we relied on the treating physician’s interpretation to determine the clinical relevance of an isolate. We have no other way of determining whether the isolate was causing disease, but we believe that this limitation is indicative of general clinical practice. Determining causality would require a different series of mechanistic investigations.

Our study demonstrates that C. striatum is an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Our results highlight the need to identify corynebacteria to the species level, which is now readily performed by using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, and perform susceptibility testing for any isolate that is believed to be clinically meaningful. The frequent resistance of C. striatum to all easily tolerated oral antimicrobial drugs supports the need for development of new agents with good oral bioavailability and acceptable long-term safety profiles that are active against gram-positive organisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nic Dobbins, Eusung (Sally) Lee, and Robert Harrington for their assistance with the electronic database system (the Institute of Translational Health Science De-Identified Clinical Data Repository).

This study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000423). W.O.H. was supported in part by an institutional training grant (T32 AI007044) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. B.J.W. has received research funding from Merck (Kenilworth, NJ, USA) and Allergan (Parsippany–Troy Hills, NJ, USA).

Biography

Dr. Hahn is an acting instructor in the Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. His primary research interest is host–pathogen interactions.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Hahn WO, Werth BJ, Butler-Wu SM, Rakita RM. Multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum associated with increased use of parenteral antimicrobial drugs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Nov [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2211.160141

Current affiliation: University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA.

References

- 1.Gavin SE, Leonard RB, Briselden AM, Coyle MB. Evaluation of the rapid CORYNE identification system for Corynebacterium species and other coryneforms. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1692–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernández Guerrero ML, Molins A, Rey M, Romero J, Gadea I. Multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium successfully treated with daptomycin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:373–4 . 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rufael DW, Cohn SE. Native valve endocarditis due to Corynebacterium striatum: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:1054–61. 10.1093/clinids/19.6.1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mashavi M, Soifer E, Harpaz D, Beigel Y. First report of prosthetic mitral valve endocarditis due to Corynebacterium striatum: Successful medical treatment. Case report and literature review. J Infect. 2006;52:e139–41. 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marull J, Casares PA. Nosocomial valve endocarditis due to corynebacterium striatum: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:388. 10.1186/1757-1626-1-388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melero-Bascones M, Muñoz P, Rodríguez-Créixems M, Bouza E. Corynebacterium striatum: an undescribed agent of pacemaker-related endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:576–7. 10.1093/clinids/22.3.576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tattevin P, Crémieux AC, Muller-Serieys C, Carbon C. Native valve endocarditis due to Corynebacterium striatum: first reported case of medical treatment alone. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:1330–1. 10.1093/clinids/23.6.1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Martínez L, Suárez AI, Rodríguez-Baño J, Bernard K, Muniáin MA. Clinical significance of Corynebacterium striatum isolated from human samples. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:634–9. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00470.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagrou K, Verhaegen J, Janssens M, Wauters G, Verbist L. Prospective study of catalase-positive coryneform organisms in clinical specimens: identification, clinical relevance, and antibiotic susceptibility. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;30:7–15. 10.1016/S0732-8893(97)00193-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soriano F, Zapardiel J, Nieto E. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Corynebacterium species and other non-spore-forming gram-positive bacilli to 18 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:208–14. 10.1128/AAC.39.1.208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual A, Bernard K, Suárez AI. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Corynebacterium striatum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2671–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoo G, Kim J, Uh Y, Lee HG, Hwang GY, Yoon KJ. Multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum bacteremia: first case in Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35:472–3. 10.3343/alm.2015.35.4.472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campanile F, Carretto E, Barbarini D, Grigis A, Falcone M, Goglio A, et al. Clonal multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum strains, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:75–8. 10.3201/eid1501.080804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werth BJ, Hahn WO, Butler-Wu SM, Rakita RM. Emergence of high-level daptomycin resistance in Corynebacterium striatum in two patients with left ventricular assist device infections. Microb Drug Resist. 2016;22:233–7. 10.1089/mdr.2015.0208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verroken A, Bauraing C, Deplano A, Bogaerts P, Huang D, Wauters G, et al. Epidemiological investigation of a nosocomial outbreak of multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum at one Belgian university hospital. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:44–50. 10.1111/1469-0691.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TT, Jaijakul S, Lewis CT, Diaz L, Panesso D, Kaplan HB, et al. Native valve endocarditis caused by Corynebacterium striatum with heterogeneous high-level daptomycin resistance: collateral damage from daptomycin therapy? Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:3461–4. 10.1128/AAC.00046-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard K, Pacheco AL. In vitro activity of 22 antimicrobial agents against Corynebacterium and Microbacterium species referred to the Canadian National Microbiology Laboratory. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 2015;37:187–98 . 10.1016/j.clinmicnews.2015.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hudspeth MK, Hunt Gerardo S, Citron DM, Goldstein EJ. Evaluation of the RapID CB Plus system for identification of Corynebacterium species and other gram-positive rods. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:543–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suwantarat N, Weik C, Romagnoli M, Ellis BC, Kwiatkowski N, Carroll KC. Practical utility and accuracy of matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry for identification of Corynebacterium species and other medically relevant Coryneform-like bacteria. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145:22–8. 10.1093/ajcp/aqv006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria; 2nd edition (M45–A2). Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Methods for antimicrobial dilution and disk susceptibility testing of infrequently isolated or fastidious bacteria; 3rd edition (M45–ED3). Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Common terminology criteria for adverse events v3.0 (CTCAE) 2006. Aug 9 [cited 2016 Aug 12]. http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcaev3.pdf

- 23.Otsuka Y, Ohkusu K, Kawamura Y, Baba S, Ezaki T, Kimura S. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum as a nosocomial pathogen in long-term hospitalized patients with underlying diseases. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;54:109–14. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watkins DA, Chahine A, Creger RJ, Jacobs MR, Lazarus HM. Corynebacterium striatum: a diphtheroid with pathogenic potential. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:21–5. 10.1093/clinids/17.1.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McElvania TeKippe E, Thomas BS, Ewald GA, Lawrence SJ, Burnham C-AD. Rapid emergence of daptomycin resistance in clinical isolates of Corynebacterium striatum… a cautionary tale. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:2199–205. 10.1007/s10096-014-2188-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee PP, Ferguson DA Jr, Sarubbi FA. Corynebacterium striatum: an underappreciated community and nosocomial pathogen. J Infect. 2005;50:338–43. 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nhan T-X, Parienti J-J, Badiou G, Leclercq R, Cattoir V. Microbiological investigation and clinical significance of Corynebacterium spp. in respiratory specimens. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74:236–41. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomila M, Renom F, Gallegos MC, Garau M, Guerrero D, Soriano JB, et al. Identification and diversity of multiresistant Corynebacterium striatum clinical isolates by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and by a multigene sequencing approach. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:52. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:e1–25. 10.1093/cid/cis803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barr DA, Semple L, Seaton RA. Self-administration of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy and risk of catheter-related adverse events: a retrospective cohort study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:2611–9. 10.1007/s10096-012-1604-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephens JM, Gao X, Patel DA, Verheggen BG, Shelbaya A, Haider S. Economic burden of inpatient and outpatient antibiotic treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft-tissue infections: a comparison of linezolid, vancomycin, and daptomycin. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:447–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morata L, Tornero E, Martínez-Pastor JC, García-Ramiro S, Mensa J, Soriano A. Clinical experience with linezolid for the treatment of orthopaedic implant infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69(Suppl 1):i47–52. 10.1093/jac/dku252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang S, Yao L, Hao X, Zhang X, Liu G, Liu X, et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of linezolid for the treatment of XDR-TB: a study in China. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:161–70. 10.1183/09031936.00035114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]