Abstract

Differentiating benign and malignant biliary strictures is a challenging and important clinical scenario. The typical presentation is indolent and involves elevation of liver enzymes, constitutional symptoms, and obstructive jaundice with or without superimposed or recurrent cholangitis. While overall the most common causes of biliary strictures are malignant, including cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, benign strictures encompass a wide spectrum of etiologies including iatrogenic, autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, and congenital. Imaging plays a crucial role in evaluating strictures, characterizing their extent, and providing clues to the ultimate source of biliary obstruction. While ultrasound is a good screening tool for biliary ductal dilatation, it is limited by a poor negative predictive value. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography is more than 95% sensitive and specific for detecting biliary strictures with the benefit of precise anatomic localization. Other commonly employed imaging modalities include endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic ultrasound, contrast-enhanced CT, and cholangiography. First-line treatment of benign biliary strictures is endoscopic dilation and stenting. In patients with anatomy that precludes endoscopic cannulation, percutaneous biliary drain insertion and balloon dilation is preferred.

Keywords: biliary strictures, benign stricture, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram, percutaneous biliary drainage, interventional radiology

Objectives: Upon completion of this article, the reader will be able to describe the causes, imaging findings, and interventional approaches in the management of benign biliary strictures.

Accreditation: This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint providership of Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) and Thieme Medical Publishers, New York. TUSM is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit: Tufts University School of Medicine designates this journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Differentiating benign from malignant biliary strictures is clinically important, and this often presents a significant diagnostic challenge. This task is especially important to guide appropriate treatment, which dramatically differs between benign and malignant causes. Malignancy, including cholangiocarcinoma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma, is the most common overall cause of biliary strictures, comprising up to 72% of cases, with many other cases classified as indeterminate until surgical resection.1 While benign causes of biliary obstruction are less prevalent, a large number of causes are currently recognized. Cross-sectional imaging plays a crucial role in differentiating benign from malignant causes, presurgical planning, and recognition of metastatic or unresectable tumors. Nonsurgical therapeutic options for benign biliary strictures include endoscopic dilatation and stenting. Percutaneous options include fluoroscopic-guided biliary decompression using percutaneous transhepatic cholangioplasty or biliary drainage catheters. In this review, we present the common causes, imaging findings, and treatment of benign biliary strictures.

Causes of Benign Biliary Stricture

A wide variety of infectious, inflammatory, congenital, autoimmune, and postsurgical disorders cause benign strictures. The most common causes include iatrogenic bile duct injuries following orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) or cholecystectomy, accounting for up to 80% of all benign strictures in the western world.2 Autoimmune and inflammatory conditions associated with biliary strictures include primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis in isolation or in association with autoimmune pancreatitis, sarcoidosis, and eosinophilic cholangitis.3 Mirizzi syndrome results in biliary strictures when it is complicated by chronic pancreatitis (in 8.2–13.9% of patients) or by chronic extrinsic compression and fibrosis of the common hepatic duct.4 Infectious bacterial and viral causes include recurrent pyogenic cholangitis and HIV-induced cholangiopathy. Cases of inflammatory biliary pseudotumors have also been reported, with speculation of a relationship with concurrent infection or autoimmune reaction.5 Primary and secondary vascular insults are known causes of biliary strictures, usually related to hepatic arterial occlusion following liver transplant or vasculitis-related ischemia.6 Conversely, still other causes of benign biliary stricture exist (Table 1).

Table 1. Benign biliary strictures: etiologies and radiologic findings.

| Causes | Imaging features |

|---|---|

| Iatrogenic | Unifocal extrahepatic stricture occurring at the level of an injured extrahepatic bile duct. Single stricture seen at the level of a hepatoenteric or end-to-end biliary anastomosis due to scarring. Unifocal anastomotic or multifocal nonanastomotic strictures occur following OLT |

| Duct injury following cholecystectomy | |

| Orthotropic liver transplant | |

| Partial hepatectomy | |

| Hepaticojejunostomy | |

| Chemotherapy | Predominant involvement of the common hepatic duct or confluence, uncommon involvement of CBD, or intrahepatic ducts |

| Radiation | |

| Autoimmune | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Multifocal diffuse alternating short segmental stenoses and mild dilatations of intrahepatic bile ducts leading to a classic “beaded” or “pruned tree” appearance, diverticulum-like outpouchings |

| IgG4 sclerosing disease | Stricture of distal CBD most common; however, can have diffuse involvement of extra- and intra-hepatic ducts, ductal wall thickening and enhancement, long-segment strictures with poststenotic dilatation, gallbladder wall thickening, absence of liver parenchymal abnormalities |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Eosinophilic cholangitis | |

| Inflammatory | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | Distal CBD stricture with evidence of chronic pancreatitis |

| Inflammatory pseudotumors | Often demonstrate malignant features and are mistaken for cholangiocarcinoma |

| Mastocytosis | Radiologic features similar to PSC |

| Infectious | |

| HIV cholangiopathy | Long-segment extrahepatic strictures, ampullary stenosis with or without multifocal intrahepatic strictures and dilatations, isolated intrahepatic sclerosing cholangitis |

| Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis | Intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal dilatation with predominance in left lateral and right posterior lobes, multiple large intraductal stones, ductal wall thickening and enhancement, periductal signal alteration, abscess |

| Parasitic infections | Radiologic features similar to RPC |

| Obstructive | |

| Mirizzi syndrome | Stones in the cystic duct or gallbladder neck with upstream dilatation of the hepatic ducts and normal caliber CBD |

| Portal cholangiopathy | Portal cavernous transformation with periportal collaterals causes extrinsic compression of the CBD |

| Choledocholithiasis | CBD stricture or stone, gallstones, pancreatitis |

| Ischemia | |

| Hepatic artery compromise | Radiologic features include multifocal nonanastomotic strictures following OLT |

| Vasculitis | |

Abbreviations: CBD, common bile duct; OLT, orthotopic liver transplant; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; RPC, recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.

Iatrogenic Biliary Injury

The most common cause of benign biliary stricture in the United States is iatrogenic injury, most commonly due to complication following cholecystectomy or liver transplant. Injury to the common bile duct (CBD) during laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy accounts for the majority of iatrogenic bile duct injuries. However, the overall reported incidence of benign biliary strictures in patients following cholecystectomy is low (0.2–0.7%). These strictures usually occur in the common hepatic duct or CBD due to inadvertent ligation during surgery.7 While some injuries are recognized intraoperatively at the time of surgery, many patients present in the early and late postoperative period with obstructive jaundice or peritonitis. Delayed bile duct injuries can present with biliary strictures months or years following surgery.8 Imaging commonly reveals upstream intrahepatic ductal dilatation and smooth, gradual tapering of the extrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 1).9

Fig. 1.

Patient with a history of liver transplant. (a) Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography image shows a stricture of the common bile duct at the surgical anastomosis (arrow) with mild proximal ductal dilatation. A 10F 15-cm stent was placed across the stricture. (b) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows a linear band at the level of the anastomosis (arrow) suspicious for stricture with mild intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilatation.

Biliary strictures following OLT follow one of the following two varieties: proximal stricture at the level of the anastomosis or peripheral stricture due to hepatic arterial compromise and ischemic cholangiopathy. Biliary complications usually occur within the first 3 months; however, strictures can form even years after the procedure.10 The average time to development of biliary stricture is 5 to 8 months following transplantation, with 70 to 87% occurring within 1 year.11 12 Strictures at the end-to-end anastomosis are reported to occur in 8 to 30% of liver transplants and typically occur due to scarring and fibrosis of the suture site.10 13 Conversely, nonanastomotic strictures are thought to be related to hepatic arterial thrombosis or stenosis. The anastomosed hepatic artery supplies total arterial flow to the transplant biliary epithelium; thus, hypoperfusion results in infarction of the biliary epithelium and often results in stricturing anywhere in the biliary tree, including the intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts, subsequently leading to graft failure. Similar to the aforementioned mechanism, complicated biliary reconstructive procedures including Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy can also develop strictures at the level of the biliary enteric anastomosis.14

Greyscale ultrasound is often the first imaging study performed for imaging of strictures in patients following orthotopic liver transplant; however, strictures cannot be excluded based on a negative ultrasound study.15 Upstream bile ducts are less prone to show significant dilation in liver transplantation. The sensitivity of ultrasound in this setting is high, reported at 71%.16 Positive findings include intrahepatic ductal dilatation as well as dilatation of the CBD proximal to the anastomosis. Color Doppler evaluation may reveal arterial waveforms with a tardus parvus morphology, suggesting arterial stenosis, or even complete absence of flow in the case of thrombosis. If ultrasound is negative or equivocal, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be performed, which is more than 95% sensitive and specific for detecting anastomotic strictures. The lesions classically appear as short-segment focal stenotic segments near the surgical anastomosis.17 18 Nonanastomotic strictures often appear as longer segments in the extra- or intrahepatic biliary system.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

PSC is a chronic progressive liver disease of unknown etiology characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, usually leading to end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis. The disease affects men twice as frequently as women, with an age of onset of 30 to 40 years, and 60 to 80% of patients present with concomitant inflammatory bowel disease, predominantly ulcerative colitis.19 The imaging study of choice in this case is MRCP, which demonstrates a classic pattern of multifocal alternating intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatations and stenoses with a “beaded” appearance (Fig. 2). In end-stage disease, the peripheral ducts are obliterated, leading to the “pruned tree” sign (Fig. 3). Other imaging findings include secondary signs of cirrhosis such as central caudate lobe hypertrophy with peripheral atrophy, leading to a lobulated contour. Diverticuli with intraductal stones are also commonly seen.

Fig. 2.

Patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. (a) Ultrasound with color Doppler shows mild intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation (arrow). (b) Image obtained during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows a short-segment stricture of the common bile duct near the hilum with alternating segments of mild biliary dilatation and intrahepatic strictures. (c and d) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography images show a “bead on a string” appearance of the intrahepatic bile ducts.

Fig. 3.

A second patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis. (a) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image reveals the “pruned tree” appearance of abruptly tapering distal intrahepatic bile ducts and mild intrahepatic biliary dilatation. (b) Image obtained during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows multifocal short-segment stenoses at the biliary bifurcation with a dominant hilar stricture and mild upstream dilatation. The patient was treated with sphincterotomy and balloon dilation.

IgG4-Related Sclerosing Cholangitis

A relatively newly recognized distinct clinical entity, IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis comprises a subset of sclerosing cholangitis. While the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is recognized as a part of the spectrum of IgG4-related disease which may or may not include autoimmune pancreatitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and sialadenitis.20 The diagnosis is made histologically by an abundant IgG4-positive plasma cell infiltrate and periportal fibrosis.

Imaging characteristics assume one of the following four different patterns: (1) distal CBD stricture, (2) diffuse intra- and extrahepatic strictures, (3) hilar and distal CBD stricture, and (4) isolated hilar stricture (Figs. 4 and 5).21

Fig. 4.

Patient with autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis and pancreatitis. (a) Image obtained during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows a 10-mm segmental narrowing of the distal common bile duct (arrow) with mild upstream dilatation. Multifocal strictures of the pancreatic duct with evidence of pancreatitis were also noted. (b) T2-weighted coronal magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography image shows a dilated common bile duct which smoothly tapers distally (arrow) with a focal short-segment stricture of the intrapancreatic bile duct.

Fig. 5.

Patient with IgG4-related autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis and pancreatitis. (a) T1-weighted axial postcontrast magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image shows subtle linear peripheral enhancement of the pancreatic body (arrow). (b) Coronal T2-weighted MRCP image shows intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with an abrupt stenosis of the common bile duct at the level of the pancreatic head (arrow).

Chronic Pancreatitis and Choledocholithiasis

Ten percent of all benign strictures are caused by pancreatitis, with the prevalence of strictures in patients with chronic pancreatitis reaching 46%.22 The intrapancreatic portion of the distal CBD is most commonly affected. MRCP reveals smooth, gradual narrowing of the CBD just above the ampulla with upstream dilatation. Other imaging findings may include an abrupt stenosis of the distal CBD and findings suggestive of chronic pancreatitis, including pancreatic parenchymal atrophy and ductal dilatation.

Patients with choledocholithiasis develop CBD strictures due to chronic scarring and fibrosis of the extrahepatic ducts from chronic obstruction. MRCP is highly sensitive and specific for the detection of CBD stones, which appear as T2 hypointense filling defects. Strictures appear as short, segmental narrowed segments above or below the level of the obstructing stone.23

Infection

The main subtypes of infection which cause chronic benign biliary strictures are HIV cholangiopathy and recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.

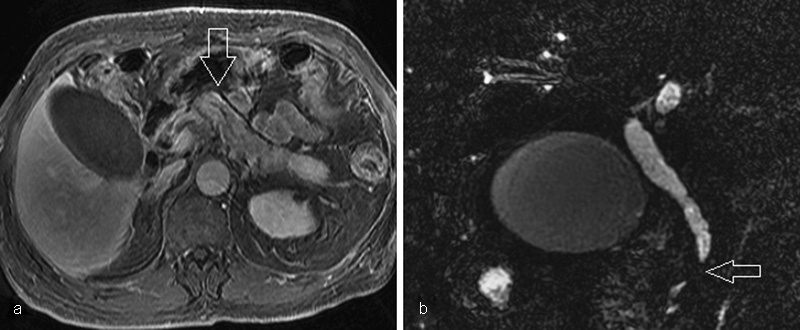

HIV cholangiopathy is a form of sclerosing cholangitis which is seen in patients with a CD4 count less than 100 cells/mm3. Opportunistic infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Cryptosporidium account for biliary inflammation. Other agents include microsporidium and giardia. Infection usually manifests as multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic strictures similar to PSC, isolated long-segment extrahepatic strictures, and ampullary stenosis (Fig. 6).24 25

Fig. 6.

Patient with pathology-proven recurrent pyogenic cholangitis and periportal fibrosis status posthepatic lobectomy. (a) Coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) image shows marked left lobar intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation with multifocal short-segment strictures and stones (arrow). (b) Axial T2-weighted MRCP image shows multiple intrahepatic stones (arrow).

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is a disease that almost solely affects patients in Southeast Asia. While the exact cause is unknown, chronic parasitic infection with parasites (Ascariasis lumbricoides and Clonorchis sinensis) or gram-negative rods has been hypothesized along with environmental factors such as malnutrition. Classic imaging findings include intraductal pigment stones, multiple intrahepatic biliary strictures, and intrahepatic and extrahepatic ductal dilatation with a predilection for the lateral segment of the left lobe or posterior segment of the right lobe.26 Other common imaging findings include complications such as abscesses, fistulas, and bilomas (Fig. 3). It is important to remember that these patients are at increased risk for cholangiocarcinoma.27

Lesion Classification

Biliary strictures are stratified under the Bismuth classification, a scheme intended to aid surgical planning.28 Under the classification system, there are five types of strictures based on the anatomic level of obstruction and proximity to the hilar confluence, from most proximal to distal. Importantly, type I and II lesions are proximal to the confluence, allowing for less invasive repair. Types III and IV involve the left and right hepatic duct confluence and require lowering the hilar plate or two or more anastomoses. Type V lesions involve both the hepatic duct and a right intrahepatic branch.

Loss or interruption of biliary confluence represents a particularly technical challenge for the surgical team in cases where operative management is necessary. Surgical options in these cases include Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy or hepatic wedge resection with neoconfluence reconstruction, with a reported success rate of up to 88% in the setting of iatrogenic bile duct injury.29

Role of Imaging

Biliary strictures are usually accompanied by upstream ductal dilatation. Ultrasound is a sensitive tool for detecting intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation and is thus generally the first choice screening exam for the evaluation of biliary obstruction. While the accuracy of ultrasound in the detection of biliary dilatation is greater than 90%, its accuracy in the detection of the underlying cause is lower, varying from 30 to 70%.30 Ultrasound is limited in its ability to depict the stricture itself. Thus, an abnormal ultrasound or normal ultrasound in the setting of high clinical suspicion should be followed by higher resolution cross-sectional imaging.

One of the most important roles of imaging in the setting of biliary strictures is the differentiation of benign from malignant lesions. Multiphase contrast-enhanced CT can be useful for this purpose. The typical imaging clues which help delineate malignant strictures on CT include biliary hyperenhancement, wall thickness greater than 1.5 mm, irregular asymmetric wall thickening with shouldered margins, and long segment strictures. Conversely, benign lesions tend to demonstrate smooth, regular, short-segmental narrowing.31 CT also provides the benefit of detecting metastatic lesions in the case of malignancy as well as detecting the underlying cause of obstruction and any associated complications.

MRCP is a highly accurate imaging modality that has been widely adopted in the evaluation of biliary obstruction, with a reported diagnostic sensitivity of up to 98%.32 However, the sensitivity of MRCP for the differentiation of benign from malignant strictures is weaker, ranging from 30 to 98%.33 34 MRCP uses heavily T2-weighted sequences to highlight the static biliary fluid and create high-resolution images. Images are obtained in two dimensions using a single section, T2-weighted, single-shot breath-hold RARE/FSE sequence or in three dimensions using fast-recovery fast-spin echo.35 MRCP is able to confirm the presence of a stricture, define its anatomic level, visualize intraductal stones as small as 2 mm in size, and exclude an underlying mass.36 The findings on MRCP which suggest a benign etiology are similar to those seen on CT: smooth, segmental narrowing without underlying mass.37 Importantly, MRCP is especially useful and often diagnostic in the evaluation of PSC, iatrogenic bowel injuries, and anastomotic strictures without the need for direct tissue sampling.

Another valuable imaging modality is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with or without endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which has demonstrated up to 97% sensitivity and 88% specificity in differentiating benign from malignant strictures.38 EUS provides the added benefit of allowing for tissue sampling with cytologic brushings or fine needle aspiration; further interventions including balloon angioplasty or stent insertion can also be performed concomitantly. Intraductal endoscopic ultrasound (IDUS) is a newer technique which utilizes a high-frequency, wire-guided ultrasound probe that is inserted into the extrahepatic bile ducts during ERCP. IDUS with ERCP has shown the ability to diagnose biliary strictures caused by malignant tumors which were not visible on CT.39 ERCP/IDUS may have superior diagnostic accuracy than MDCT or EUS alone.40 The drawback of ERCP with IDUS/EUS is its requirement for an invasive endoscopic procedure with risks such as biliary or bowel perforation. The finding on EUS most associated with benign stricture is the preservation of the normal sonographic layers of the bile duct wall.39 40

Endoscopic Management

While the most effective treatment in each case is tailored to the patient, endoscopic visualization with balloon angioplasty and/or stenting is widely considered first-line management of suspected benign or indeterminate biliary strictures. Often multiple sessions are required. Endoscopic stents currently deployed include plastic and fully covered self-expandable metal stents. The goal of therapeutic intervention is long-term biliary decompression with preservation of bile duct patency. Alternatively, endoscopic decompression can be used as a bridge to surgery.41

Balloon dilatation of a benign stricture is usually combined with stenting and rarely performed in isolation. Balloon dilatation alone results in up to 47% restenosis.41 42 43 The main indication for balloon dilatation alone is in the setting of PSC with a dominant stricture. Multiple retrospective studies have shown clinical response in up to 80% of patients with PSC treated with angioplasty alone, and stent placement has not shown additional benefit.44 45 46 47 48 Insertion of a single plastic stent is rarely performed due to low patency rates; rather, several overlapping plastic stents are deployed during multiple endoscopic sessions. Self-expandable, fully covered metal stents are covered in a membrane that prevents soft-tissue hyperplasia, thus allowing for easier removal. These provide an alternative solution and have mostly replaced the use of plastic stents due to their relative ease of removal, longer patency, and increased diameter.49 Bare metal stents are no longer used for benign strictures, as they can create irreversible hyperplasia that prevents removal due to embedment within the biliary epithelium.50 More data are needed to investigate the efficacy of covered, self-expanding metal stents versus multiple plastic stents, both of which are currently regularly utilized.

Percutaneous Management

Percutaneous therapy is indicated in patients with strictures not amenable to endoscopic treatment. Endoscopic evaluation may be impossible for patients with postsurgical anatomic variations of the proximal bowel, including those who have undergone a hepaticojejunal anastomosis to a Roux-en-Y limb, Whipple procedure, Billroth II surgery, or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Another precluding condition is severe duodenal or papillary stenosis preventing CBD cannulation or postpyloric passage of the endoscope.

Advantages of fluoroscopic evaluation include the ability to precisely define the anatomy of the bile tree with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC), locate the level of obstruction, and identify obstructing lesions or stones.51 PTC also enables direct access to the biliary tree, allowing for percutaneous decompression, balloon dilatation, or stone removal. PTC is indicated when ERCP has failed or is contraindicated especially in the setting of sepsis or multiple comorbid conditions. PTC with decompression may be an acceptable first-line management option in the setting of dominant biliary stricture. Conversely, percutaneous drain placement is not preferred in the setting of multifocal obstruction such as in PSC.51 Finally, PTC may be indicated in patients with complicated tight hilar strictures, where reaching the distal end of the stricture is incomplete.36 The only contraindication to PTC is significant irreversible coagulopathy.

PTC Technique, PBD, and Balloon Dilation

After obtaining informed consent and administering preoperative antibiotics, the patient is placed in the supine position. Access into the biliary tree is achieved via two main approaches: right midaxillary and left subxiphoid. The right midaxillary approach is more commonly employed; however, the approach should be tailored to the location of the dominant stricture and to operator experience. Classic teaching instructs needle placement at the level of the 11th intercostal space in the midaxillary line or three-finger breadths below the xyphoid.52 A 22-gauge Chiba needle is used to gain access to a peripheral bile duct, and following sequential exchange using a coaxial system a sheath is placed with or without a safety guidewire. Often in the setting of benign strictures, the intrahepatic ducts are only mildly dilated, making peripheral puncture more difficult. In this setting, a central puncture is performed with a second Chiba needle, through which a cholangiography is performed to guide a fluoroscopic puncture. A cholangiography is then performed through a 5F angiocatheter or 7 to 8F vascular access sheath to reveal the level of obstruction. The decision to cross the stricture then must be made. In the setting of difficult catheterization or cholangitis, an external drain may be placed temporarily to allow for decompression and the patient may be brought back in several weeks to attempt crossing.

Once the stricture is successfully crossed, a second decision must be made whether to (1) place an internal–external locked multi–side hole biliary drain, (2) perform balloon dilation, or (3) both. Most benign biliary strictures are amenable to balloon dilation except in the setting of new bilioenteric anastomosis, where postoperative edema often resolves with time and does not respond well to intervention. Balloon dilation of new surgical anastomoses can be potentially harmful and may lead to bile leak. Finally, short-segment strictures respond better to balloon dilation than long-segment ones, with short-term patency rates of 50 to 90% and long-term patency rates of 56 to 74%.53 54 55 56 57

Most benign strictures are amenable to balloon dilation. An 8- to 10-mm-wide and 2- to 4-cm-long balloon is often used to dilate a proximal CBD or common hepatic duct stricture; however, larger balloons can be used, especially at the biliary-enteric anastomosis. The balloon is inflated for at least 1 minute and is usually reinflated several times. An internal–external locking catheter is then inserted with side holes both proximal and distal to the stenosis. Following balloon dilation, the catheter can be upsized sequentially up to approximately 16F over multiple sessions. In most centers, patients return every 3 to 6 weeks for repeat cholangiography, balloon dilation, and catheter upsizing.58 Patients with recalcitrant strictures may require larger or higher pressure balloons or a double-barrel technique.59

Successful dilation will be evident on sheath cholangiography with evidence of prompt excretion of contrast without residual stenosis. A capping trial will be attempted for several weeks with an external drain. In the absence of symptoms suggesting obstruction (cholangitis, jaundice, fever, elevated liver enzymes, and leakage around the catheter) and evidence of continued patency, the drain may then be removed. A recent study showed successful drain removal in 87% of patients who completed a full period of 6 to 12 months of sequential upsizing and dilation with a stricture patency rate of 84% at 1 year, 74% at 5 years, and 67% at 10 years.60 Permanent indwelling of internal–external catheter may be required in patients who fail dilation therapy. In this case, patients must return every 3 months for catheter exchange to prevent occlusion.

As noted earlier, bare metal stents have no role in the management of benign biliary strictures due to their high rates of occlusion and irretrievability. Unlike endoscopic management, stents are generally only deployed percutaneously for strictures resistant to balloon dilation. As described previously, fully covered, self-expandable metallic stents have shown promising results when deployed endoscopically. A recent study of 68 patients who were treated percutaneously with fully covered metallic stents showed a clinical success rate of 87% in patients with both primary and refractory strictures and a patency rate of 91% at 1 year.61 Finally, the VIABIL nonporous expanded polytetrafluoroethylene/fluorinated ethylene propylene lined stent with atraumatic self-anchoring fins has shown promise for patients with hepaticojejunostomy strictures; however, stent migration was high at 21%.62 More data are needed to confirm safety and long-term efficacy of fully covered stents deployed percutaneously for treatment of benign strictures.

Conclusion

A large number of diseases encompassing a broad spectrum of pathology can cause benign biliary strictures. Imaging plays a critical role in differentiating benign from malignant strictures. It is important for the radiologist to be familiar with the common imaging appearances of benign strictures and to correlate these findings with the patient's history, symptoms, and laboratory values to formulate an accurate differential diagnosis. First-line management of benign biliary strictures is ERCP with or without EUS. In the setting of contraindications to endoscopic cannulation such as surgically altered anatomy, percutaneous intervention is an acceptable alternative. PTC with balloon dilation and internal–external drain placement is the standard therapy practiced by interventional radiologists. Fully covered, self-expandable metal stents have shown promising results and may be used more often by both interventional radiologists and gastroenterologists in the future.

References

- 1.Tummala P, Munigala S, Eloubeidi M A, Agarwal B. Patients with obstructive jaundice and biliary stricture±mass lesion on imaging: prevalence of malignancy and potential role of EUS-FNA. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(6):532–537. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182745d9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judah J R, Draganov P V. Endoscopic therapy of benign biliary strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(26):3531–3539. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowlus C L, Olson K A, Gershwin M E. Evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(1):28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo I, Nagamine N, Nakamura Y, Nikuma H, Kato S. On the Mirizzi syndrome—benign stenosis of the hepatic duct induced by a stone in the cystic duct or the neck of the gallbladder. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1979;14(2):155–161. doi: 10.1007/BF02773588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koide H, Sato K, Fukusato T. et al. Spontaneous regression of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with primary biliary cirrhosis: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(10):1645–1648. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i10.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Op den Dries S, Sutton M E, Lisman T, Porte R J. Protection of bile ducts in liver transplantation: looking beyond ischemia. Transplantation. 2011;92(4):373–379. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318223a384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanbhogue A K, Tirumani S H, Prasad S R, Fasih N, McInnes M. Benign biliary strictures: a current comprehensive clinical and imaging review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197(2):W295–306. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kukar M, Wilkinson N. Surgical management of bile duct strictures. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(2):125–132. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0972-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heller M T, Borhani A A, Furlan A, Tublin M E. Biliary strictures and masses: an expanded differential diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(6):1944–1960. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berrocal T, Parrón M, Alvarez-Luque A, Prieto C, Santamaría M L. Pediatric liver transplantation: a pictorial essay of early and late complications. Radiographics. 2006;26(4):1187–1209. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah S A, Grant D R, McGilvray I D. et al. Biliary strictures in 130 consecutive right lobe living donor liver transplant recipients: results of a Western center. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(1):161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim P T, Marquez M, Jung J. et al. Long-term follow-up of biliary complications after adult right-lobe living donor liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2015;29(5):465–474. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barriga J, Thompson R, Shokouh-Amiri H. et al. Biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Predictive factors for response to endoscopic management and long-term outcome. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335(6):439–443. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318157d3b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamine R, Shibata T, Yabuta M. et al. Long-term outcome of percutaneous biliary interventions for biliary anastomotic stricture in pediatric patients after living donor liver transplantation with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(12):1852–1859. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keogan M T, McDermott V G, Price S K, Low V H, Baillie J. The role of imaging in the diagnosis and management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(1):215–219. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.1.10397129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beswick D M, Miraglia R, Caruso S. et al. The role of ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for the diagnosis of biliary stricture after liver transplantation. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(9):2089–2092. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pecchi A, De Santis M, Gibertini M C. et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2011;43(4):1132–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valls C, Alba E, Cruz M. et al. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: diagnosis with MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(3):812–820. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.3.01840812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escorsell A Parés A Rodés J Solís-Herruzo J A Miras M de la Morena E; Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis in Spain J Hepatol 1994215787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakazawa T, Naitoh I, Hayashi K, Miyabe K, Simizu S, Joh T. Diagnosis of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(43):7661–7670. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Sano H, Ando T, Joh T. Schematic classification of sclerosing cholangitis with autoimmune pancreatitis by cholangiography. Pancreas. 2006;32(2):229. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202941.85955.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdallah A A, Krige J E, Bornman P C. Biliary tract obstruction in chronic pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9(6):421–428. doi: 10.1080/13651820701774883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi E C, Ham J M. Benign biliary strictures associated with chronic pancreatitis and gallstones. Aust N Z J Surg. 1980;50(5):488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1980.tb04176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ducreux M, Buffet C, Lamy P. et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of AIDS-related cholangitis. AIDS. 1995;9(8):875–880. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199508000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bilgin M, Balci N C, Erdogan A, Momtahen A J, Alkaade S, Rau W S. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic MRI and MRCP findings in patients with HIV infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191(1):228–232. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jain M, Agarwal A. MRCP findings in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen M F, Jan Y Y, Wang C S. et al. A reappraisal of cholangiocarcinoma in patient with hepatolithiasis. Cancer. 1993;71(8):2461–2465. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2461::aid-cncr2820710806>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bismuth H, Majno P E. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25(10):1241–1244. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercado M A, Vilatoba M, Contreras A. et al. Iatrogenic bile duct injury with loss of confluence. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(10):254–260. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i10.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blackbourne L H, Earnhardt R C, Sistrom C L, Abbitt P, Jones R S. The sensitivity and role of ultrasound in the evaluation of biliary obstruction. Am Surg. 1994;60(9):683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi S H, Han J K, Lee J M. et al. Differentiating malignant from benign common bile duct stricture with multiphasic helical CT. Radiology. 2005;236(1):178–183. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J Y, Lee J M, Lee J Y. et al. Navigator-triggered isotropic three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in the diagnosis of malignant biliary obstructions: comparison with direct cholangiography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(1):94–101. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee M G, Lee H J, Kim M H. et al. Extrahepatic biliary diseases: 3D MR cholangiopancreatography compared with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1997;202(3):663–669. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim M J, Mitchell D G, Ito K, Outwater E K. Biliary dilatation: differentiation of benign from malignant causes—value of adding conventional MR imaging to MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 2000;214(1):173–181. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.1.r00ja35173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katabathina V S, Dasyam A K, Dasyam N, Hosseinzadeh K. Adult bile duct strictures: role of MR imaging and MR cholangiopancreatography in characterization. Radiographics. 2014;34(3):565–586. doi: 10.1148/rg.343125211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Byrne M F. Management of benign biliary strictures. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2008;4(10):694–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suthar M, Purohit S, Bhargav V, Goyal P. Role of MRCP in differentiation of benign and malignant causes of biliary obstruction. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(11):TC08–TC12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/14174.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Materne R, Van Beers B E, Gigot J F. et al. Extrahepatic biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance imaging compared with endoscopic ultrasonography. Endoscopy. 2000;32(1):3–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saifuku Y, Yamagata M, Koike T. et al. Endoscopic ultrasonography can diagnose distal biliary strictures without a mass on computed tomography. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(2):237–244. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heinzow H S, Kammerer S, Rammes C, Wessling J, Domagk D, Meister T. Comparative analysis of ERCP, IDUS, EUS and CT in predicting malignant bile duct strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(30):10495–10503. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan C H, Telford J J. Endoscopic management of benign biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22(3):511–537. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith M T, Sherman S, Lehman G A. Endoscopic management of benign strictures of the biliary tree. Endoscopy. 1995;27(3):253–266. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Foutch P G, Sivak M V Jr. Therapeutic endoscopic balloon dilatation of the extrahepatic biliary ducts. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80(7):575–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Milligen de Wit A W, van Bracht J, Rauws E A, Jones E A, Tytgat G N, Huibregtse K. Endoscopic stent therapy for dominant extrahepatic bile duct strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44(3):293–299. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(96)70167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.May G R, Bender C E, LaRusso N F, Wiesner R H. Nonoperative dilatation of dominant strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145(5):1061–1064. doi: 10.2214/ajr.145.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dickson E R, Murtaugh P A, Wiesner R H. et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: refinement and validation of survival models. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(6):1893–1901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91449-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baluyut A R, Sherman S, Lehman G A, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Impact of endoscopic therapy on the survival of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53(3):308–312. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(01)70403-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaya M, Petersen B T, Angulo P. et al. Balloon dilation compared to stenting of dominant strictures in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):1059–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Devière J Nageshwar Reddy D Püspök A et al. Successful management of benign biliary strictures with fully covered self-expanding metal stents Gastroenterology 20141472385–395., quiz e15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferreira R, Loureiro R, Nunes N. et al. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of benign biliary strictures: What's new? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;8(4):220–231. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i4.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fidelman N. Benign biliary strictures: diagnostic evaluation and approaches to percutaneous treatment. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;18(4):210–217. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Venbrux A, Osterman F. New York, NY: Little Brown; 1997. Malignant obstruction of the hepatobiliary system; pp. 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Köcher M, Cerná M, Havlík R, Král V, Gryga A, Duda M. Percutaneous treatment of benign bile duct strictures. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62(2):170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cantwell C P, Pena C S, Gervais D A, Hahn P F, Dawson S L, Mueller P R. Thirty years' experience with balloon dilation of benign postoperative biliary strictures: long-term outcomes. Radiology. 2008;249(3):1050–1057. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491080050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zajko A B, Sheng R, Zetti G M, Madariaga J R, Bron K M. Transhepatic balloon dilation of biliary strictures in liver transplant patients: a 10-year experience. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1995;6(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weber A, Rosca B, Neu B. et al. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) in patients with benign bilioenterostomy stricture. Endoscopy. 2009;41(4):323–328. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramos-De la Medina A, Misra S, Leroy A J, Sarr M G. Management of benign biliary strictures by percutaneous interventional radiologic techniques (PIRT) HPB (Oxford) 2008;10(6):428–432. doi: 10.1080/13651820802392304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krokidis M, Orgera G, Rossi M, Matteoli M, Hatzidakis A. Interventional radiology in the management of benign biliary stenoses, biliary leaks and fistulas: a pictorial review. Insights Imaging. 2013;4(1):77–84. doi: 10.1007/s13244-012-0200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gwon D I, Sung K B, Ko G Y, Yoon H K, Lee S G. Dual catheter placement technique for treatment of biliary anastomotic strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(2):159–166. doi: 10.1002/lt.22206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DePietro D M, Shlansky-Goldberg R D, Soulen M C. et al. Long-term outcomes of a benign biliary stricture protocol. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26(7):1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gwon D I, Ko G Y, Ko H K, Yoon H K, Sung K B. Percutaneous transhepatic treatment using retrievable covered stents in patients with benign biliary strictures: mid-term outcomes in 68 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(11):3270–3279. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2784-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hwang G L, Louise J D, Hofmann L. et al. Outcomes of viabil covered stent placement for treatment of hepaticojejunostomy strictures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24(4):S54. [Google Scholar]