Abstract

AIM

To evaluate the effect of norepinephrine on inflammatory cytokine expression in ex vivo human monocytes and monocytic THP-1 cells.

METHODS

For human monocyte studies, cells were isolated from 12 chronic heart failure (HF) (66 ± 12 years, New York Heart Association functional class III-IV, left ventricular ejection fraction 22% ± 9%) and 14 healthy subjects (66 ± 12 years). Monocytes (1 × 106/mL) were incubated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) 100 ng/mL, LPS + norepinephrine (NE) 10-6 mol/L or neither (control) for 4 h. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) production were determined by ELISA. Relative contribution of α- and β-adrenergic receptor subtypes on immunomodulatory activity of NE was assessed in LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells incubated with NE, the α-selective agonist phenylephrine (PE), and the β-selective agonist isoproterenol (IPN). NE-pretreated THP-1 cells were also co-incubated with the β-selective antagonist propranolol (PROP), α2-selective antagonist yohimbine (YOH) or the α1-selective antagonist prazosin (PRAZ).

RESULTS

Basal TNFα concentrations were higher in HF vs healthy subjects (6.3 ± 3.3 pg/mL vs 2.5 ± 2.6 pg/mL, P = 0.004). Norepinephrine’s effect on TNFα production was reduced in HF (-41% ± 17% HF vs -57% ± 9% healthy, P = 0.01), and proportionately with NYHA FC. Increases in IL-10 production by NE was also attenuated in HF (16% ± 18% HF vs 38% ± 23% healthy, P = 0.012). In THP-1 cells, NE and IPN, but not PE, induced a dose-dependent suppression of TNFα. Co-incubation with NE and antagonists revealed a dose-dependent inhibition of the NE suppression of TNFα by PROP, but not by YOH or PRAZ. Dose-dependent increases in IL-10 production were seen with NE and IPN, but not with PE. This effect was also antagonized by PROP but not by YOH or PRAZ. Pretreatment of cells with IPN attenuated the effects of NE and IPN, but did not induce a response to PE.

CONCLUSION

NE regulation of monocyte inflammatory cytokine production may be reduced in moderate-severe HF, and may be mediated through β-adrenergic receptors.

Keywords: Monocytes, Cytokines, Heart failure, Inflammation

Core tip: In evaluating the relationship between sympathetic activation and inflammatory cytokine production in heart failure, we demonstrated that norepinephrine (NE) has reduced ability to suppress the production of the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and increase anti-inflammatory interleukin-10, in human isolated monocytes from heart failure compared to healthy subjects. It appears to be mediated through beta-adrenergic, and not alpha-adrenergic, receptors based on monocytic THP-1 cells dose-response experiments. This suggests that the diminished immunomodulatory activity of NE in heart failure is primarily due to altered beta-adrenergic receptor function, and may represent an immunologic mechanism for the positive effects of beta-adrenergic blocking agents.

INTRODUCTION

The importance of inflammatory cytokines to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) has been recognized for many years[1]. Much of the focus has been on proinflammatory tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) which has been shown to be cardiodepressant, contributes to exercise intolerance, and modulates apoptosis, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction[2,3]. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) antagonizes the inflammatory effects of TNFα. Both TNFα and IL-10 plasma levels are elevated in HF patients, although the increase in IL-10 is proportionately less, supporting the notion of a proinflammatory state[4].

Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production is regulated by the adrenergic nervous system. Previous studies have demonstrated that β2-, but not β1-, receptor agonists attenuate TNFα expression, while increasing anti-inflammatory IL-10 production[5,6]. Conversely, α1,2-adrenergic stimulation results in increased expression of TNFα and reduction in IL-10[7]. Under normal physiologic conditions, norepinephrine, an α- and β-agonist, reduces TNFα and enhances IL-10 expression in monocytes exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other stimuli[8]. However, in HF a paradox exists as both catecholamines and TNFα are elevated, which suggests that this negative feedback mechanism may be impaired. The mechanism for the diminished immunomodulatory response to norepinephrine in HF is also unknown but could occur secondary to the altered adrenergic expression and function known to exist in the failing heart.

The study purpose was to evaluate whether attenuation of TNFα production and augmentation of IL-10 production by the adrenergic agonist norepinephrine is altered in chronic HF compared to healthy, age-matched controls utilizing the model of LPS-stimulated monocytes. In addition, preliminary experiments were undertaken to determine the relative contribution of α- and β-adrenergic receptor subtypes on the immunomodulatory activity of norepinephrine in monocytic THP-1 cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolated human monocytes

HF subjects were recruited from the cardiology clinics and the University Hospital at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Subjects, male or female, were eligible for inclusion if they had: Clinical HF (LVEF < 40% on 2D-ECHO or MUGA within last 3 mo), New York Heart Association Functional Class (NYHA FC) III-IV HF, and were over 30 years of age. Exclusion criteria included: Primary restrictive or valvular HF, acute viral illness or bacterial infection, history of autoimmune disease, concurrent therapy with systemic norepinephrine, known anemia (Hgb < 10 mg/dL) or other contraindication to giving blood. Healthy subjects over the age of 30 were recruited from the University of Nebraska Medical Center through a posting on the university Intranet. All human subjects gave informed consent for their participation. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university.

Monocyte isolation was performed following a standard Nycodenz protocol[9], from 12 HF [age 66 ± 12 years old, New York Heart Association Functional Class (NYHA FC) 6 III, 6 IV, mean left ventricular ejection fraction 20% ± 10%] and 14 healthy subjects (age 66 ± 12 years). Aliquoted (1 x 106/mL) monocytes were incubated with LPS 100 ng/mL, LPS + norepinephrine 10-6 mol/L or neither (negative control) for 4 h (all reagents from Sigma Chemical Co., Westbury, NY). Previous work demonstrated maximal stimulation of cytokines using the specified reagent concentrations and incubation time. TNFα and IL-10 production were determined by assaying the supernatant using commercially available enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA) kits (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

THP-1 cells

THP-1 cells were cultured and assayed in a supplemented RPMI media (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were aliquoted into 1 × 106 cells/mL samples for experiments. Dose-response curves were determined for TNFα and IL-10 production in LPS-stimulated (100 ng/mL) THP-1 cell samples incubated with norepinephrine (10-5 to 10-10 mol/L), the α-selective agonist phenylephrine (PE) (10-6 to 10-10 mol/L) and the β-selective agonist isoproterenol (IPN) (10-5 to 10-10 mol/L). LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells were also co-incubated with a fixed concentration of norepinephrine 10-6 mol/L, which provided maximal effect in agonist experiments, and the β-selective antagonist propranolol (PROP) (10-5 to 10-10 mol/L), α2-selective antagonist yohimbine (YOH) (10-6 to 10-10 mol/L) or the α1-selective antagonist prazosin (PRAZ) (10-6 to 10-10 mol/L), for generation of dose-response curves. TNFα and IL-10 production was assessed as described above. Samples were assayed in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

To control for inherent inter-subject differences in constitutive production of cytokines, changes in TNFα and IL-10 concentrations are expressed as percent reduction by norepinephrine + LPS compared to LPS only for each sample. Comparison of percent reduction in TNFα and IL-10 concentrations from isolated monocytes of controls and HF subjects was performed by an independent two sample t test. Significance was set at P < 0.05. Results are reported as mean ± SD. Comparative effects on cytokine production in THP-1 cells between the different α- and β-adrenergic reagents was assessed via visual inspection of the dose-response curves as this was a preliminary study. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Mimi Lou, MS (biostatistician) from the University of Southern California School of Pharmacy.

RESULTS

Isolated human monocytes

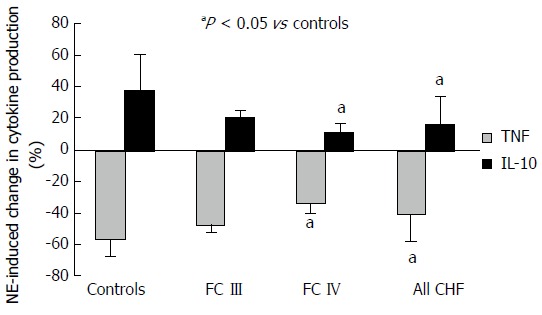

Study subject characteristics are described in Table 1. Basal TNFα concentrations (supernatant) were higher in HF than healthy subjects (6.3 ± 3.3 pg/mL vs 2.5 ± 2.6 pg/mL, P = 0.004). Norepinephrine reduction of TNFα production was significantly reduced in monocytes from HF subjects (-41% ± 17% HF vs -57% ± 9% healthy, P = 0.01). Norepinephrine-induced increases in monocyte IL-10 production was also reduced in HF (16% ± 18% HF vs 38% ± 23% healthy, P = 0.012). The diminished response to norepinephrine appeared related to severity of HF, with a greater diminution for both TNFα and IL-10 in NYHA FC IV vs NYHA FC III and controls (Figure 1). A signal for reduced IL-10 response in patients with left ventricular ejection fractions ≤ 20% when compared to those with left ventricular ejection fractions > 20% (7% ± 12 vs 25% ± 20%, P = 0.07) was also present. There were no differences in cytokine response based on the presence or absence of beta-blocker (BB) therapy (TNFα: -37% ± 17% no BB vs -46% ± 17% BB, P = 0.9; IL-10: 11% ± 13% no BB vs 20% ± 22% BB, P = 0.3), or HF etiology (TNFα: -41% ± 17% ischemic vs -42% ± 18% non-ischemic, P = 0.7; IL-10: 20% ± 19% ischemic vs 8% ± 15% non-ischemic, P = 0.5).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| % | Heart failure (n = 12) | Healthy subjects (n = 14) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 66 ± 12 | 66 ± 12 | 0.994 |

| Male | 67 | 36 | 0.238 |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 92 | 100 | 0.462 |

| LVEF | 22 ± 9 | ||

| Diabetes | 33 | 0 | 0.033 |

| CAD | 50 | 0 | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 25 | 29 | 1.000 |

| Medications | |||

| Beta-blocker | 50 | 0 | |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 75 | 7 | |

| Loop diuretic | 100 | 0 | |

| ARA | 42 | 0 | |

| Hydralazine/isosorbide dinitrate | 8 | 0 | |

| Amiodarone | 50 | 0 | |

| Digoxin | 50 | 0 | |

ACE: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARA: Aldosterone receptor blocker; ARB: Angiotensin receptor blocker; CAD: Coronary artery disease; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 1.

Comparative change in lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10 production in monocytes induced by norepinephrine between heart failure patients and normal controls. Results expressed as mean ± SD. FC: Functional classification.

THP-1 cells

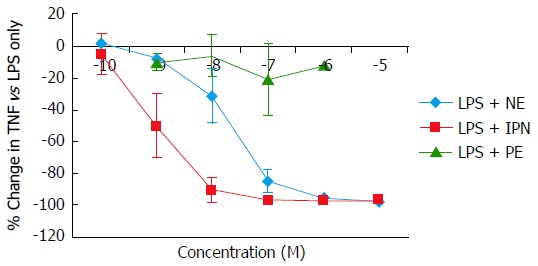

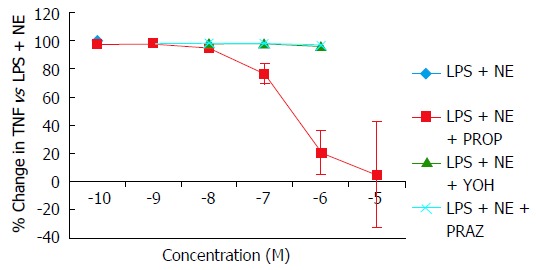

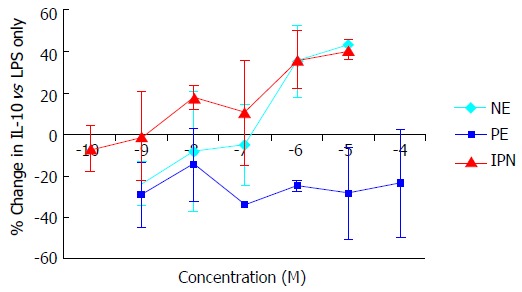

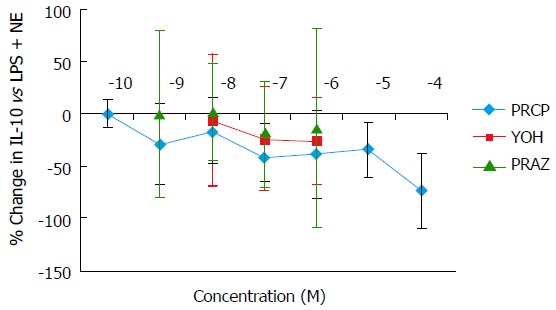

Norepinephrine and IPN, but not PE, induced a concentration-dependent suppression of TNFα production in cultured monocytic THP-1 cells. Equivalent maximal suppression was achieved with norepinephrine 10-6 mol/L or IPN 10-7 mol/L (Figure 2). Co-incubation of THP-1 cells with LPS, norepinephrine and selective adrenergic receptor antagonists revealed a concentration-dependent inhibition of the norepinephrine suppression of TNFα by PROP, but not by YOH or PRAZ. Maximal blockade of norepinephrine’s effects was obtained at PROP 10-5 mol/L (Figure 3). Concentration-dependent increases in IL-10 production were seen with norepinephrine and IPN, but not with PE (Figure 4). This effect was also antagonized by PROP but not by YOH or PRAZ (Figure 5). Pretreatment of cells with IPN (10-7 mol/L) for 4 h attenuated the effects of norepinephrine and IPN, but pretreatment did not induce a response to PE (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent changes in lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in monocytic THP-1 cells induced by the α-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine and the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Results expressed as mean ± SD. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; NE: Norepinephrine; IPN: Isoproterenol; PE: Phenylephrine.

Figure 3.

Concentration-dependent changes in norepinephrine attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in monocytic THP-1 cells blocked by the α1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin, the α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine, and the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol. Results expressed as mean ± SD. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; NE: Norepinephrine; PE: Phenylephrine; PROP: Propranolol; YOH: Yohimbine; PRAZ: Prazosin.

Figure 4.

Concentration-dependent changes in interleukin-10 production in THP-1 cells induced by the α-adrenergic agonist phenylephrine and the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol. Results expressed as mean ± SD. NE: Norepinephrine; IPN: Isoproterenol; PE: Phenylephrine; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; IL: Interleukin.

Figure 5.

Concentration-dependent changes in norepinephrine attenuation of interleukin-10 production in THP-1 cells blocked by the α1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin, the α2-adrenergic antagonist yohimbine, and the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol. Results expressed as mean ± SD. LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; NE: Norepinephrine; PE: Phenylephrine; PROP: Propranolol; YOH: Yohimbine; PRAZ: Prazosin.

DISCUSSION

Our preliminary findings suggest norepinephrine’s ability to regulate monocyte inflammatory cytokine production may be reduced in moderate to severe HF. The ability of norepinephrine to exert an overall anti-inflammatory effect on the balance of production of TNFα and IL-10 appears to be reduced in proportion to disease severity, as indicated by the a greater diminution of the induced cytokine response in monocytes isolated from NYHA functional class IV as compared to functional class III patients and controls. This is the first report demonstrating monocyte TNFα/IL-10 responsiveness to norepinephrine is diminished in HF and provides a novel mechanism to explain increased production of TNFα in HF. Our results are consistent with a study demonstrating a reduced inhibitory effect of norepinephrine on TNFα production assessed in whole blood of HF patients[10]. Our results also agree with other studies demonstrating basal monocytic inflammatory cytokine production is upregulated in chronic HF[11,12].

In addition, based on our experiments in monocytic THP-1 cells, norepinephrine’s immunomodulatory effect in monocytes is likely secondary to activation of β-adrenergic receptors, with no or little involvement of α-adrenergic receptors. This was evidenced by the concentration-dependent reduction of TNFα and augmentation of IL-10 production by norepinephrine and isoproterenol, but not by phenylephrine. The effect of norepinephrine could also be antagonized by β-receptor blockade with propranolol, whereas α1 and α2-blocking agents had no effect. This is consistent with other investigations and provides a plausible mechanism for the diminished cytokine response to norepinephrine observed in HF[13-16]. Altered β-adrenergic receptor function and expression have been well characterized in the failing heart[17,18]. Beta1-adrenergic receptor density and function is reduced in the failing heart, while beta-2-adrenergic receptor expression remains essentially unchanged[19]. This shift in importance towards the beta-2-adrenergic receptor would suggest immunomodulatory response to catecholamines would be preserved, however, other pathophysiologic alterations may still occur that change or limit their functionality[20,21]. In addition, norepinephrine is known to have low affinity for beta2-adrenergic receptors, but showed similar maximal effects comparable to isoproterenol[22,23]. Therefore, whether the observed immunomodulatory response to norepinephrine is mediated solely through beta2-adrenergic receptors requires confirmation.

The study has important limitations. The human monocyte experiment sample size is small. Unfortunately we did not have an adequate number of human monocytes to evaluate adrenoreceptor expression between HF and healthy subjects which would strengthen these preliminary findings as THP-1 are a monocytic cell-line but may not be identical to human monocytes. We also did not examine the isolated effects of the receptor antagonists propranolol, yohimbine and prazosin as we are not aware of literature suggesting a direct effect on inflammatory cytokine production, only modulation in a proinflammatory model[6,7,13,14,24-27]. As such, the results of this study are preliminary and should be interpreted as hypothesis generating. Further studies are required to determine whether monocyte production of other cytokines exhibit a similar reduction in response to catecholamine stimulation in HF, to fully characterize the mechanism for the observed impaired catecholamine-cytokine response, and to devise pharmacologic strategies to normalize cytokine responsiveness to the adrenergic nervous system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Amy Vrana for her help performing assays for this study. The authors would also like to thank Tom Sears, MD for his assistance with identifying heart failure subjects for the study.

COMMENTS

Background

Inflammation has been recognized as a major contributing factor to the pathophysiology of heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) for many years. However, attempts to improve the prognosis of HFrEF patients by targeting proinflammatory cytokines have failed largely in part to an incomplete understanding of the mechanisms which contribute to the initiation and perpetuation of their expression. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production is regulated by the adrenergic nervous system. Under normal physiologic conditions, norepinephrine, an α- and β-agonist, reduces tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and enhances interleukin-10 expression in monocytes exposed to lipopolysaccharide and other stimuli. However, in HFrEF a paradox exists as both catecholamines and TNFα are elevated, which suggests that this negative feedback mechanism may be impaired.

Research frontiers

HF is recognized as a proinflammatory syndrome, and that inflammatory pathways likely contribute to the decline in cardiac function. However, the mechanisms for initiation or persistence of the proinflammatory balance are poorly described and remain an area of active investigation. Clinical trials of agents targeting proinflammatory cytokines have failed to improve long term prognosis of HF patients. A major explanation for the failures is an incomplete understanding of mechanisms underlying the proinflammatory state.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Although it has been described that catecholamines reduce proinflammatory cytokine production, this is the first study to demonstrate that attenuation of monocyte inflammatory cytokine production by norepinephrine is reduced in cells isolated from HF patients compared to healthy individuals.

Applications

The findings are mainly descriptive but may represent a novel pathway for the proinflammatory state in patients with HF. If alterations in β-adrenergic receptor function is a mechanism for the diminished counter-regulatory response to norepinephrine in HF, some of the benefit of beta-adrenergic receptor blockers in HF may be due to immunomodulatory or anti-inflammatory effects. These preliminary findings need confirmation in future studies.

Peer-review

The manuscript is interesting because it adds new information concerning mechanisms underlying this proinflammatory state.

Footnotes

Supported by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy Research Institute.

Institutional review board statement: Study was approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Informed consent statement: The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university. All human subjects gave signed informed consent for their participation.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the study.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: March 15, 2016

First decision: April 20, 2016

Article in press: August 18, 2016

P- Reviewer: Amiya E, Gong KZ, Grignola J, Iacoviello M, Lymperopoulos A S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Mann DL, Young JB. Basic mechanisms in congestive heart failure. Recognizing the role of proinflammatory cytokines. Chest. 1994;105:897–904. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.3.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1201–1206. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer M. Is tumor necrosis factor an important neurohormonal mechanism in chronic heart failure? Circulation. 1995;92:1379–1382. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamaoka M, Yamaguchi S, Okuyama M, Tomoike H. Anti-inflammatory cytokine profile in human heart failure: behavior of interleukin-10 in association with tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Jpn Circ J. 1999;63:951–956. doi: 10.1253/jcj.63.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Severn A, Rapson NT, Hunter CA, Liew FY. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor production by adrenaline and beta-adrenergic agonists. J Immunol. 1992;148:3441–3445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guirao X, Kumar A, Katz J, Smith M, Lin E, Keogh C, Calvano SE, Lowry SF. Catecholamines increase monocyte TNF receptors and inhibit TNF through beta 2-adrenoreceptor activation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:E1203–E1208. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.6.E1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spengler RN, Allen RM, Remick DG, Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Stimulation of alpha-adrenergic receptor augments the production of macrophage-derived tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol. 1990;145:1430–1434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chelmicka-Schorr E, Kwasniewski MN, Czlonkowska A. Sympathetic nervous system and macrophage function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;650:40–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb49092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bøyum A. Isolation of human blood monocytes with Nycodenz, a new non-ionic iodinated gradient medium. Scand J Immunol. 1983;17:429–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1983.tb00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Haehling S, Genth-Zotz S, Bolger AP, Kalra PR, Kemp M, Adcock IM, Poole-Wilson PA, Dietz R, Anker SD. Effect of noradrenaline and isoproterenol on lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in whole blood from patients with chronic heart failure and the role of beta-adrenergic receptors. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:885–889. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conraads VM, Bosmans JM, Schuerwegh AJ, Goovaerts I, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ, Bridts CH, Vrints CJ. Intracellular monocyte cytokine production and CD 14 expression are up-regulated in severe vs mild chronic heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:854–859. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amir O, Spivak I, Lavi I, Rahat MA. Changes in the monocytic subsets CD14(dim)CD16(+) and CD14(++)CD16(-) in chronic systolic heart failure patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:616384. doi: 10.1155/2012/616384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakamura A, Johns EJ, Imaizumi A, Yanagawa Y, Kohsaka T. Effect of beta(2)-adrenoceptor activation and angiotensin II on tumour necrosis factor and interleukin 6 gene transcription in the rat renal resident macrophage cells. Cytokine. 1999;11:759–765. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshimura T, Kurita C, Nagao T, Usami E, Nakao T, Watanabe S, Kobayashi J, Yamazaki F, Tanaka H, Inagaki N, et al. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1-beta production by beta-adrenoceptor agonists from lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Pharmacology. 1997;54:144–152. doi: 10.1159/000139481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szabó C, Haskó G, Zingarelli B, Németh ZH, Salzman AL, Kvetan V, Pastores SM, Vizi ES. Isoproterenol regulates tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-10, interleukin-6 and nitric oxide production and protects against the development of vascular hyporeactivity in endotoxaemia. Immunology. 1997;90:95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abraham E, Kaneko DJ, Shenkar R. Effects of endogenous and exogenous catecholamines on LPS-induced neutrophil trafficking and activation. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L1–L8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.1.L1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harding SE, Brown LA, Wynne DG, Davies CH, Poole-Wilson PA. Mechanisms of beta adrenoceptor desensitisation in the failing human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drosatos K, Lymperopoulos A, Kennel PJ, Pollak N, Schulze PC, Goldberg IJ. Pathophysiology of sepsis-related cardiac dysfunction: driven by inflammation, energy mismanagement, or both? Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2015;12:130–140. doi: 10.1007/s11897-014-0247-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bristow MR, Sandoval AB, Gilbert EM, Deisher T, Minobe W, Rasmussen R. Myocardial alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors in heart failure: is cardiac-derived norepinephrine the regulatory signal? Eur Heart J. 1988;9 Suppl H:35–40. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/9.suppl_h.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Capote LA, Mendez Perez R, Lymperopoulos A. GPCR signaling and cardiac function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;763:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lymperopoulos A, Rengo G, Koch WJ. Adrenergic nervous system in heart failure: pathophysiology and therapy. Circ Res. 2013;113:739–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mickey JV, Tate R, Mullikin D, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of adenylate cyclase-coupled beta adrenergic receptor binding sites by beta adrenergic catecholamines in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 1976;12:409–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lymperopoulos A, Garcia D, Walklett K. Pharmacogenetics of cardiac inotropy. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15:1807–1821. doi: 10.2217/pgs.14.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Li J, Sheng X, Zhao H, Cao XD, Wang YQ, Wu GC. Beta-adrenoceptor mediated surgery-induced production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in rat microglia cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;223:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong J, Mrabet O, Moze E, Li K, Neveu PJ. Lateralization and catecholaminergic neuroimmunomodulation: prazosin, an alpha1/alpha2-adrenergic receptor antagonist, suppresses interleukin-1 and increases interleukin-10 production induced by lipopolysaccharides. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2002;10:163–168. doi: 10.1159/000067178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finck BN, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Woods JA, Johnson RW. Central lipopolysaccharide elevates plasma IL-6 concentration by an alpha-adrenoreceptor-mediated mechanism. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:R1880–R1887. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.272.6.R1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JD, Campisi J, Sharkey CM, Kennedy SL, Nickerson M, Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Catecholamines mediate stress-induced increases in peripheral and central inflammatory cytokines. Neuroscience. 2005;135:1295–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]