Abstract

Purpose: We evaluated the outcomes of open heart surgery and long-term quality of life for patients 85 years and older.

Methods: We enrolled 46 patients 85 years and older who underwent cardiac and thoracic aortic surgery between May 1999 and November 2012. Long-term assessment was performed for 43 patients; three patients who died in the hospital were excluded. Patient conditions were assessed before surgery, 6 months and 12 months after surgery, and during the late period regarding the need for nursing care, degree of independent living, and living willingness.

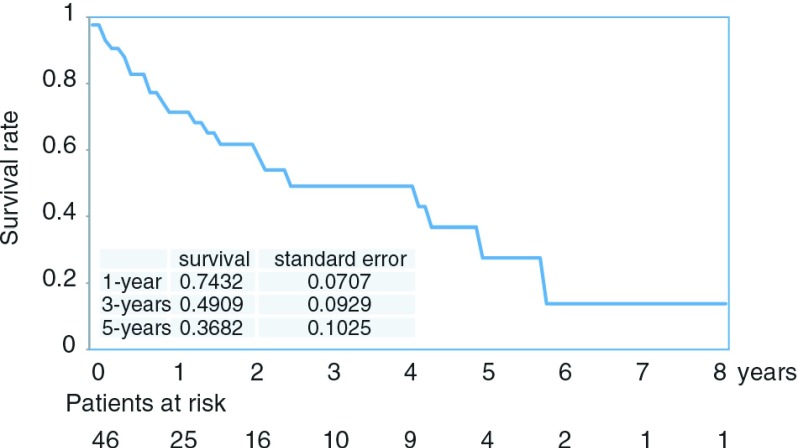

Results: Three patients (6.5%) died during hospitalization and 22 (51%) died during the follow-up period. The 1-, 3-, 5-year survival rates were 74%, 49%, and 36%. During the late period, of 21 surviving patients, 18 patients (85%) were living at home. The need for nursing care was comparable before and after surgery. The degree of independent living decreased after surgery. Living willingness was similar before and after surgery.

Conclusion: Among patients 85 years or older who underwent open heart surgery, 85% were living at home. All patients could perform activities of daily living without any assistance while maintaining living willingness.

Keywords: cardiovascular surgery, elderly patient, over 85 years, activities of daily living, quality of life

Introduction

Populations of developed countries tend to reach ages older than those of undeveloped countries. The population of Japan in particular has been aging at a rate that has not been previously noted anywhere worldwide. Sporadic reports have also described older age among cardiovascular surgery patients.1–14) For elderly patients, the indications for surgery should be considered while accounting for various risks, which differ from those for younger patients. Cardiovascular surgery for elderly patients aged ≥85 years is associated with very high risk, and we have to carefully consider surgical treatment for these patients. While considering cardiac surgery for elderly patients, parameters should be assessed different from those used for younger patients. These include the need for nursing care, degree of independent living, and living willingness, all of which account for patient dignity as well as social living. Thus, postsurgical quality of life (QOL) and activities of daily living (ADL) have received increased attention in recent years.15–19) For patients at extremely high risk in whom aortic valve replacement (AVR) is difficult to perform, minimally invasive trans-catheter aortic valve implantation is now available, and treatment strategies have been carefully evaluated and selected. In the present study, the significance of open heart surgery for elderly patients 85 years or older was evaluated by examining short-term and long-term prognoses after open heart surgery, detailed long-term QOL, and factors affecting short-term prognosis.

Materials and Methods

There were 2469 patients (older than 85 years, 46 [18.6%]; 80–84 years, 213 [86.3%]; 70–79 years, 921 [37.3%]; 60–69 years, 683 [27.6%]; 50–59 years, 363 [14.9%]; 40–49 years, 137 [5.5%]; younger than 39 years, 106 [4.3%]) who underwent cardiac and thoracic aortic surgery at Nagasaki University Hospital between May 1999 and November 2012. The 46 patients (19 men and 27 women) aged ≥85 years at the time of surgery were examined (Table 1). The age at the time of surgery ranged from 85 to 91 years (mean, 86.6 years). Surgical procedures were as follows: simple coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) in 18 patients (39%); single valve surgery in 9 patients (19.5%); combined surgery in 7 patients (15.2%); aortic replacement in 10 patients (21%); and left ventricular repair in 2 patients (4.3%) (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient's characteristics.

| No. of patients | 46 |

| Follow-up rate | 100% (46/46) |

| Sex (male/female) | 19/27 |

| Age (years) | 86.6 ± 1.8 |

| Body weight(Kg) | 52.18 ± 16.47 |

| BSA(m2) | 1.36 ± 0.34 |

| Hb(g/dl) | 11.7 ± 1.7 |

| Alb(g/dl) | 3.5 ± 0.59 |

| Follow-up period (years) | 3.3 ± 3.1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (15%) |

| Hypertension | 32 (69%) |

| Reoperation | 1 (2%) |

| NYHA ≥III | 13 (28%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (13%) |

| COPD | 2 (4.3%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 (17%) |

| Renal insufficiency (Cre ≥2.0 mg/dL) | 3 (6.5%) |

| Hemodialysis | 1 (2%) |

| Liver dysfunction (T-Bil >2.0 mg/dL) | 0 (0%) |

NYHA: New York Heart Association; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cre: creatinine; T-Bil: total bilirubin value; BSA: body surface area; Hb: hemoglobin; Alb: albumin

Table 2. Operative procedure.

| Simple CABG | 18 (39%) |

| Single valve surgery | 9 (19.5%) |

| AVR | 7 |

| TVR | 1 |

| MV plasty | 1 |

| Combined surgery | 7 (15.2%) |

| MVR + TVR | 1 |

| AVR + MV plasty + PV isolation | 1 |

| AVR + CABG | 1 |

| AVR + VSD closure | 1 |

| MV plasty + CABG | 1 |

| MV palsty + Remove of myxoma | 1 |

| CABG + Remove of myxoma | 1 |

| Aortic replacement | 10 (21%) |

| Ascending aorta | 4 |

| Aortic arch | 1 |

| Descending aorta | 4 |

| Thoracoabdominal aorta | 1 |

| Other | |

| LV repair | 2 (4.3%) |

AVR: aortic valve replacement; MVR: mitral valve replacement; MV plasty: mitral valve plasty; TVR: tricuspid valve replacement; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; VSD: ventricular septal defect; LV repair: left ventricular repair; PV: pulmonary vain

Long-term assessment was performed for 43 patients (3 patients who died in the hospital were excluded; follow-up rate, 100%; mean follow-up period, 25 ± 23 months; maximum follow-up period, 8.41 years). Twenty-one out those 43 patients (22 patients died and were excluded) survived for more than 6 months and were assessed before surgery (21 patients), at 6 months (21 patients) and 12 months (16 patients) after surgery, and during the late period (>18 months after surgery; 15 patients) using the following three instruments: the Barthel Index (BI; 100-point scale), Fillenbaum instrumental activities of daily living scale (Fillenbaum IADL; 5-point scale), and the Vitality Index (VI; 10-point scale).20–23) The BI was used to assess the need for care.20) The total score was 100, with score ≤20 indicating totally dependent, score ≤40 indicating severe impairment, and score ≥60 indicating highly independent. The Fillenbaum IADL was used to assess ability of independent living.21,22) The highest score was 5, and score ≥4 indicated a high level of independence. The Fillenbaum IADL was used together with the BI to evaluate and assess the ability of independent social living. The VI was used to assess motivation (volition) for living. The highest score was 10, and score ≥7 indicated motivation for living.

To estimate the ADL scale and to compare results against those of the 25 patients with severe aortic stenosis aged 80 to 84 years, the BI, Fillenbaum IADL, and VI were used (Table 3).

Table 3. Patient's characteristics of the 25 patients of severe aortic stenosis from 80 to 84 years old.

| No. of patients | 25 |

| Sex (male/female) | 7/18 |

| Age (years) | 82 ± 1.5 |

| Body weight(Kg) | 51.5 ± 10.5 |

| BSA(m2) | 1.45 ± 0.17 |

BSA: body surface area

The survey was conducted using mailed questionnaires and telephone questionnaires. Factors affecting short-term prognosis were statistically analysed using the χ2 test and logistic regression. Survival rates were analysed by Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Ethical approval was obtained from an institutional review committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before participation in the study.

Results

The 46-patient cohort comprised 18 patients undergoing CABG alone (off-pump in 12, on-pump beating in 5, and conventional in 1), 9 patients undergoing single valve surgery (AVR in 7, tricuspid valve replacement [TVR] in 1, and mitral valve [MV] repair in 1), 10 patients with thoracic aortic disease (acute dissection in 4, aortic aneurysm rupture in 4, true aortic aneurysm in 2), 2 patients undergoing ventricular septal perforation repair, and 7 patients undergoing combined surgical procedures. In-hospital death occurred in 3 patients (6.5%), including 1 with left ventricular rupture occurring 10 days after CABG for acute myocardial infarction, 1 with haemorrhagic shock occurring after surgery for acute aortic dissection, and 1 with liver failure after TVR. The mean length of hospital stay was 37 ± 36.4 days. Seven patients were discharged to home and 36 patients were transferred to other hospitals. The reason for transfer to other facilities was mainly improvement in walking ability. During the follow-up period, 22 patients (51%) died; the 1-, 3-, 5-year survival rates were 74%, 49%, and 36% (Fig. 1). Causes of death were pneumonia in 9 patients, old age in 6 patients, and other causes in 7 patients (congestive heart failure in 1, lung cancer in 1, acute aortic dissection in 1, cerebral infarction in 1, trauma in 1, intestinal necrosis in 1, unknown in 1). There was no correlation between cause of death after discharge and postoperative complications.

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier curve for long-term survival: 1-year survival, 74%; 3-year survival, 49%; and 5-year survival, 36%.

All 21 surviving patients answered the questionnaire, and 18 patients (85%) were living at home during the late period. The BI score was 92.9 ± 15.9 before surgery, 89.7 ± 12.1 at 6 months after surgery, 92.8 ± 7.89 at 12 months after surgery, and 90.3 ± 8.45 during the late period (>18 months after surgery). Although the postoperative mean values remained comparable to the preoperative mean values, all patients had a BI score exceeding 60 points, indicating that nursing care was not needed. The mean long-term IADL score was 2.13 ± 1.92, which was a decrease from the preoperative score of 3.64 ± 1.62. There were 5 patients (33.3%) with an IADL score of ≥4 points more than 18 months after surgery, which is considered to indicate the ability to live independently. The mean VI score, which was used as an index of living willingness, was 9.52 ± 0.94 before surgery, 8.09 ± 3.34 at 6 months after surgery, 7.27 ± 1.04 at 12 months after surgery, and 9.23 ± 1.08 during the late period. There were 14 patients (93.3%) with VI score ≥7 points at more than 18 months after surgery, which is considered to indicate a high willingness to undertake activities (Table 4).

Table 4. Change score of (a). Barthel Index: Need for caregiving (total score is 100 points), (b). Fillenbaum IADL: Ability for independent living (total 5 points), (c). Vitality index: Motivation for living (total 10 points).

| Mean score | Result | |

|---|---|---|

| a | No need for caregiving (score ≥60) | |

| Preoperative | 92.9 ± 15.9 | 20/21 (95.2%) |

| At 6 months | 89.7 ± 12.1 | 21/21 (100%) |

| At 12 months | 92.8 ± 7.89 | 16/16 (100%) |

| Over 18 months | 90.3 ± 8.45 | 15/15 (100%) |

| b | Highly independent (score ≥4) | |

| Preoperative | 3.64 ± 1.62 | 13/21 (61.9%) |

| At 6 months | 2.23 ± 1.95 | 6/21 (28.6%) |

| At 12 months | 2.12 ± 1.99 | 5/16 (31.2%) |

| Over 18 months | 2.13 ± 1.92 | 5/15 (33.3%) |

| c | Motivation for living (score ≥7) | |

| Preoperative | 9.52 ± 0.94 | 20/21 (95.2%) |

| At 6 months | 8.09 ± 3.34 | 20/21 (95.2%) |

| At 12 months | 7.27 ± 1.04 | 15/16 (93.8%) |

| Over 18 months | 9.23 ± 1.08 | 14/15 (93.3%) |

IADL: instrumental activities of daily living

To estimate the ADL scale, 25 patients with severe aortic stenosis who were 80 to 84 years old were assessed using the following three instruments: BI, Fillenbaum IADL, and the VI. The BI score was 97.2 ± 4.26, Fillenbaum IADL score was 4.24 ± 1.27, and VI score was 9.48 ± 0.81. When compared with the scores of the three instruments for those 85 years or older, the scores of patients with ages from 80 to 84 years were comparable (Table 4, Table 5).

Table 5. The score of Barthel Index, Fillenbaum IADL, Vitality Index of the 25 patients of severe aortic stenosis from 80 to 84 years old.

| Mean score | Conditions | |

|---|---|---|

| No need for caregiving (score ≥60) | ||

| Barthel Index | 97.2 ± 4.26 | 25/25 (100%) |

| Highly independent (score ≥4) | ||

| Fillenbaum IADL | 4.24 ± 1.27 | 21/25 (84%) |

| Motivation for living (score ≥7) | ||

| Vitality Index | 9.48 ± 0.81 | 24/25 (96%) |

IADL: instrumental activities of daily living

When single-factor analysis was performed to identify factors affecting short-term prognosis, the factors associated with early postoperative death were preoperative renal dysfunction, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, liver function, preoperative myocardial infarction, an urgent procedure, and body mass index ≤20. However, when these factors were analysed by logistic regression, none was identified as a significant factor affecting short-term prognosis.

Discussion

Although only a few articles have exclusively focused on patients older than 85 years, the reported rates of in-hospital mortality after open heart surgery for elderly patients 80 years or older range from 4% to 10% after a single surgical procedure and exceed 20% after combined surgical procedures. Many reports have described a particularly high in-hospital mortality rate after MV surgery. The 5-year survival rate for elderly patients after open heart surgery ranges from 50% to 75%,1–3) whereas the incidences of postoperative cerebral infarction and postoperative renal failure were shown to be twice as high as those for younger patients.2) According to many reports, the risks of postoperative death, neurological complications, and repeated thoracotomy to treat bleeding are higher in patients 80 years or older than in younger patients.4) In the present study, the in-hospital mortality rate was 6.5%, which appears to be an average value. Although the 5-year survival rate was 36%, this was attributed to the sole inclusion of patients 85 years or older.

In elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis, the long-term prognosis for drug therapy is reportedly poor, as indicated by 3-year survival rates ranging from 29% to 49% and 5-year survival rates ranging from 16% to 32%. Because patients undergoing AVR showed 3-year survival rates ranging from 80% to 85% and a 5-year survival rate of 73% (which are better than the rates achieved with drug therapy),5–8) surgery should be considered, even for elderly patients. Furthermore, it is assumed that the prognosis of elderly patients who develop heart failure is even worse; therefore, it seems prudent to consider surgery at an early stage.9,10)

According to various reports, in-hospital mortality after AVR for aortic stenosis ranges from 3.2% to 9% for patients 80 years or older and from 2.9% to 7.4% for younger patients or patients of all ages; therefore, the difference between these rates is minimal.11–14) Even in patients undergoing AVR combined with CABG, short-term and long-term outcomes do not vary greatly13); moreover, there was no difference in mortality, incidence of acute cerebrovascular events and postoperative myocardial infarction, postoperative dialysis rate, frequency of pacemaker placement, and incidence of major cardiovascular events including mediastinitis. An age of 80 years or older is a predictive factor for late death, but it is not considered to be a predictive factor for heart-related death or major cardiovascular events.11) The 5-year survival rate for patients 80 years or older undergoing AVR alone ranges from 56% to 90%.11–13) According to the cohort life table issued in 2013 by the Center for Cancer Control and Information Services at the Japan National Cancer Center, the Japanese general population data from the year 2000 show 5-year survival rates of 67% for men aged 80 years and 81% for women aged 80 years. Although these rates cannot be strictly compared due to differences between Japanese and overseas data, the postoperative survival rates do not appear to be inferior to the rates shown in the life table. Considering the in-hospital mortality and survival rates after discharge noted in the present study, surgery for aortic valve lesions seems appropriate for patients older than 80 years.

According to various researchers, early death occurs in 13.3% to 25% of all patients 80 years or older who undergo MV surgery.1,2,15,16) Fortunately, no early mortality occurred in our 4 patients after the surgical procedure including MV surgery.

Among our patients, 85% of those who survived the surgery were living at home; moreover, all surviving patients continued to be able to perform ADL without any assistance and maintained their living willingness. However, there was a decrease in the degree of independence required for independent living. Several studies of open heart surgery for very elderly patients have reported various results. Improvement was achieved after surgery, as assessed using the New York Heart Association classification. Furthermore, in a study using the Short Form 12 (a scale measuring health-related QOL), physical function in both male and female patients recovered to the level of the general population in the same age group, but decreased mental function was found in the female patients.17) In a study that used the Nottingham Health Profile, although conditions improved in 87% of patients postoperatively, physical activity and mental response measurements were significantly lower in patients 80 years or older than in those younger than 80 years.18) Mental health status scores were higher than those of general elderly people, but physical health status scores were comparable.3) Surgery improved lifestyle and decreased the risk of left heart failure. Despite the high risk of surgery, the benefits obtained were either comparable or exceeded those obtained by younger patients. This study indicates that elderly patients should not be denied surgery on the basis of age alone, and that early surgery can be recommended in this population, with the exception of emergency cases. In elderly patients, open heart surgery also provided sufficient postsurgical benefits in terms of QOL.19)

In elderly patients, the indications for surgery should be considered while accounting for various risks. Cardiovascular surgery for elderly patients 85 years or older is associated with very high risk, and we have to carefully consider the decision of surgical treatment. If elderly patients do not have cognitive impairment, understand their condition in detail, and express their want for cardiac surgery, then we must determine the indication for surgery in these patients. However, if the patient cannot walk because of frailty, then we may abandon surgical treatment. Among elderly patients 85 years or older who were independent in terms of ADL before surgery, those who survived the surgery had favourable QOL. Therefore, because long-term QOL was satisfactory, surgery can be considered a viable option for very elderly patients after accounting for preoperative ADL levels. However, the ability to live an independent life is decreased after surgery, and there seems to be a need to enhance community-wide systems to provide comprehensive support.

This study did have some limitations. First, this was a retrospective study at a single centre. Second, this was a questionnaire survey; therefore, subjective factors may have influenced the results. Third, because we must evaluate the QOL of elderly patients in detail with many questions, the analysis of ADL was limited to the surviving patients at the time of investigation. Obviously, we could not evaluate ADL before and after surgery of the patients who died.

Conclusion

Long-term QOL after cardiac and thoracic aortic surgery for elderly patients 85 years or older who were independent in terms of ADL before surgery was satisfactory. Therefore, surgery can be considered a viable option for very elderly patients after accounting for preoperative ADL levels. However, the ability to live an independent life is decreased after surgery, and there seems to be a need to enhance community-wide systems to provide comprehensive support.

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1).Kolh P, Kerzmann A, Lahaye L, et al. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians; peri-operative outcome and long-term results. Eur Heart J 2001; 22: 1235-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Alexander KP, Anstrom KJ, Muhlbaier LH, et al. Outcomes of cardiac surgery in patients > or = 80 years: results from the national cardiovascular network. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Ghanta RK, Shekar PS, McGurk S, et al. Long-term survival and quality of life justify cardiac surgery in the very elderly patient. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92: 851-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Johnson WM, Smith JM, Woods SE, et al. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: does age alone influence outcomes? Arch Surg 2005; 140: 1089-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Bouma BJ, van Den Brink RB, van Der Meulen JH, et al. To operate or not on elderly patients with aortic stenosis: the decision and its consequences. Heart 1999; 82: 143-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Bakaeen FG, Chu D, Ratcliffe M, et al. Severe aortic stenosis in a veteran population: treatment considerations and survival. Ann Thorac Surg 2010; 89: 453-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, et al. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82: 2111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Piérard S, Seldrum S, de Meester C, et al. Incidence, determinants, and prognostic impact of operative refusal or denial in octogenarians with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91: 1107-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Hamaguchi S, Kinugawa S, Goto D, et al. Predictors of long-term adverse outcomes in elderly patients over 80 years hospitalized with heart failure. – A report from the Japanese Cardiac Registry of Heart Failure in Cardiology (JCARE-CARD)–. Circ J 2011; 75: 2403-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Mahjoub H, Rusinaru D, Soulière V, et al. Long-term survival in patients older than 80 years hospitalised for heart failure. A 5-year prospective study. Eur J Heart Fail 2008; 10: 78-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Carnero-Alcázar M, Reguillo-Lacruz F, Alswies A, et al. Short- and mid-term results for aortic valve replacement in octogenarians. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 10: 549-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Melby SJ, Zierer A, Kaiser SP, et al. Aortic valve replacement in octogenarians: risk factors for early and late mortality. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 83: 1651-6; discussion 1656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Nikolaidis N, Pousios D, Haw MP, et al. Long-term outcomes in octogenarians following aortic valve replacement. J Card Surg 2011; 26: 466-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Amano J, Kuwano H, Yokomise H. Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery in Japan during 2011: Annual report by The Japanese Association for Thoracic Surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 61: 578-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Goldsmith I, Lip GY, Kaukuntla H, et al. Hospital morbidity and mortality and changes in quality of life following mitral valve surgery in the elderly. J Heart Valve Dis 1999; 8: 702-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Bossone E, Di Benedetto G, Frigiola A, et al. Valve surgery in octogenarians: in-hospital and long-term outcomes. Can J Cardiol 2007; 23: 223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Spaziano M, Carrier M, Pellerin M, et al. Quality of life following heart valve replacement in the elderly. J Heart Valve Dis 2010; 19: 524-32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Chocron S, Rude N, Dussaucy A, et al. Quality of life after open-heart surgery in patients over 75 years old. Age Ageing 1996; 25: 8-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Shan L, Saxena A, McMahon R, et al. A systematic review on the quality of life benefits after aortic valve replacement in the elderly. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145: 1173-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J 1965; 14: 61-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969; 9: 179-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Fillenbaum GG. Screening the elderly. A brief instrumental activities of daily living measure. J Am Geriatr Soc 1985; 33: 698-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Toba K, Nakai R, Akishita M, et al. Vitality Index as a useful tool to assess elderly with dementia. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2002; 2: 23-9. [Google Scholar]