Abstract

Objective

An American Heart Association (AHA) Science Advisory recommends patients with coronary heart disease undergo routine screening for depressive symptoms with the two-stage Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). However, little is known on the prognostic impact of a positive PHQ screen on heart failure (HF) mortality.

Methods

We screened hospitalized patients with systolic HF (left ventricle ejection fraction≤40%) for depression with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) and administered the follow-up nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) both immediately following the PHQ-2 and by telephone 1 month after discharge. Later, we ascertained vital status at 4-year follow-up on all patients who completed the inpatient PHQ-9 and calculated mortality incidence and risk by baseline PHQ.

Results

Of the 520 HF patients, we enrolled 371 screened positive for depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2. Of these, 63% scored PHQ-9≥10 versus 24% of those who completed the PHQ-9 1 month later (P<.001). PHQ-2 positive status was an independent predictor of 4-year all-cause mortality (HR: 1.50; P=.04), and mortality incidence was similar by baseline PHQ-9 score.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized patients with systolic HF, a positive PHQ-2 screen for depressive symptoms is an independent risk factor for increased 4-year all-cause mortality. Our findings extend the AHA's Science Advisory for depression to hospitalized patients with systolic HF.

Keywords: Depression, heart failure, mortality, Patient Health Questionnaire, screening

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a common and growing health problem. Over 5 million people in the United States have HF, with approximately 915,000 new cases and 300,000 deaths annually. Yet despite recent therapeutic advances in care, HF remains the only major cardiovascular disease whose mortality rate has remained essentially unchanged over the past decade [1]. One potential contributor to these persistently poor outcomes is depression. Approximately half of HF patients report elevated levels of depressive symptoms, and they are more likely to report reduced health-related quality of life, poorer adherence with evidence-based care and increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than nondepressed HF patients even after adjustment for disease severity [2–4].

Based on the accumulating evidence linking depression with worse cardiovascular outcomes, the American Heart Association (AHA) issued a Science Advisory that recommended patients with coronary heart disease to undergo routine screening and treatment for depression [5]. Specifically, the Advisory suggested a two-stage approach beginning with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2) depression screen [6], followed by administration of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [7] to screen-positive patients to assess symptom severity and guide treatment decisions. However, the Science Advisory did not specify the timing of the follow-up PHQ-9. Indeed, if the PHQ-9 is administered during hospitalization, then patients' “depressive symptoms” may be misattributed to such commonly experienced symptoms of hospitalization as fatigue, disturbances in sleep and appetite that are likely to resolve soon after discharge home [2,8]. However, waiting to administer the follow-up PHQ-9 to PHQ-2 screen-positive patients until after hospital discharge may delay the start of effective care for depression and increase suffering.

We previously reported that hospitalized patients with systolic HF who expressed that depressive symptoms on the PHQ-2 [PHQ-2 (+)] experienced an increased rate of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 1 year following discharge compared to those who did not expressive depressive symptoms [PHQ-2 (−)] even after adjustment for known predictors of HF mortality [9]. However, the prognostic durability of the PHQ-2 beyond 1 year is presently unknown. Furthermore, we did not report on the pragmatic consequences of waiting to administer the follow-up PHQ-9 until after discharge to allow time for the potential “symptoms” of hospitalization to resolve. We now examine these issues in that study cohort we enrolled to inform development of an effectiveness trial to treat depression in patients with HF we are presently conducting (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02044211).

2. Methods

Following a study protocol detailed previously [9] and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of XXX, study nurse-recruiters obtained Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) consent to approach patients hospitalized for any reason with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤40% on the medical and cardiac wards at four XXX-area acute care hospitals between December 2007 and April 2009. We targeted enrollment of 372 PHQ-2 (+) study subjects to have sufficient power to conduct six receiver operating curve analyses to determine the ideal PHQ-9 cutoff score that best predicted 6-month mortality risk separately for each New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (II–IV) by gender to inform our proposed clinical trial. Given the substantial mortality risk among nondepressed HF patients [10], we also planned to enroll 100 HF patients to serve as a nondepressed control cohort [PHQ-2 (−)]. To operationalize this, our study nurses requested HIPAA consent from hospital staff who suspected that their patients with a qualifying LVEF might be depressed.

Protocol-eligible patients were also required to report NYHA functional class level II–IV cardiac symptoms and to have no history of psychotic illness, bipolar disorder or current alcohol dependency or substance abuse disorder. After obtaining informed consent, study nurses collected sociodemographic and clinical information via patient interview, administered the PHQ-2 screen followed by the PHQ-9 and conducted a medical chart review to confirm protocol eligibility to continue in our cohort study. If so confirmed, the study nurses administered the 12-item Medical Outcomes Study Short Form to determine mental and physical health-related quality of life [11] and the PRIME-MD Anxiety Module to determine the presence of an anxiety disorder [12]. At 1 month following hospital discharge, another research assessor who was blinded as to patients' baseline PHQ-2 status and PHQ-9 score telephoned the patient to readminister the PHQ-9. We immediately notified the attending physician or primary care physician when their patient endorsed suicidal ideations on either the inpatient or 1 month follow-up PHQ-9.

2.1. PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 assessments

As recommended by the AHA Science Advisory [5], we defined a positive PHQ-2 screen for depression [PHQ-2 (+)] when a patient responded “yes” to one or both of the following questions: Over the preceding 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by: (1) “little interest or pleasure in doing things” or (2) “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”. We defined a negative PHQ-2 screen when the patient replied “not at all” to both items and was not taking an antidepressant (90% sensitivity and 69% specificity for major depressive disorder) [13]. As indication for at least moderately severe depressive symptoms, we used the generally accepted PHQ-9 cutoff score of ≥10 (52% sensitivity and 91% specificity at detecting major depression among patients with cardiac disease) [13].

2.2. Vital status

To determine vital status and cause of death for up to 4 years following the date of recruitment, we used our medical center's electronic medical records system, the Social Security Death Index, online obituary notices and telephone calls with patients' predesignated secondary contacts and primary care physicians. Afterwards, two study physicians blinded as to patients' baseline PHQ-2 status independently classified the cause of each confirmed death as “cardiovascular” (e.g., HF, arrhythmia, myocardial infarction, stroke) or “noncardiovascular” (e.g., infection, cancer, trauma).

2.3. Statistical analyses

We compared patients' baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by PHQ-2 status using t tests for continuous data and chi-square tests for categorical data, and we used the Hochberg method to control for multiple comparisons [14]. All tests were two-tailed and P values ≤.05 were considered significant; all analyses were performed with SAS statistical software version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

We used Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to calculate the incidence of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality by PHQ-2 status, with log-rank tests to evaluate differences for statistical significance. To control for possible confounders of the relationship between mood and mortality, we adjusted for several recognized of HF mortality [15,16] including diabetes, anemia (hemoglobin<10 g/dl), hyponatremia (sodium<136 mEq/L), renal insufficiency (creatinine>1.7 mg/dl), blood pressure and use of an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker medication, as well as coumadin using Cox proportional-hazard models. We also performed sensitivity analyses to assess the potential impact of missing information on the cause of death on our findings. First, we assumed that patients whose cause of death was undetermined had died of a cardiovascular cause and then, since antidepressant use may affect mortality risk [17,18], we repeated our analyses excluding patients who self-reported use of an antidepressant at baseline.

We dichotomized the PHQ-2 so that a >0 on either of the two questions was considered a positive screen as it is more likely to be utilized in this manner by busy staff in routine clinical practice settings. We categorized inpatient PHQ-9 data into groups using established PHQ-9 severity levels [7] and then applied Kaplan–Meier survival analyses to calculate the incidence of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at yearly follow-up intervals. Next we adjusted for possible confounders of the relationship between depressive symptoms and HF morbidity and mortality using Cox models. To examine for bias, we compared baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients missing 1-month PHQ-9 scores to those with complete data.

3. Results

3.1. Study recruitment and follow-up

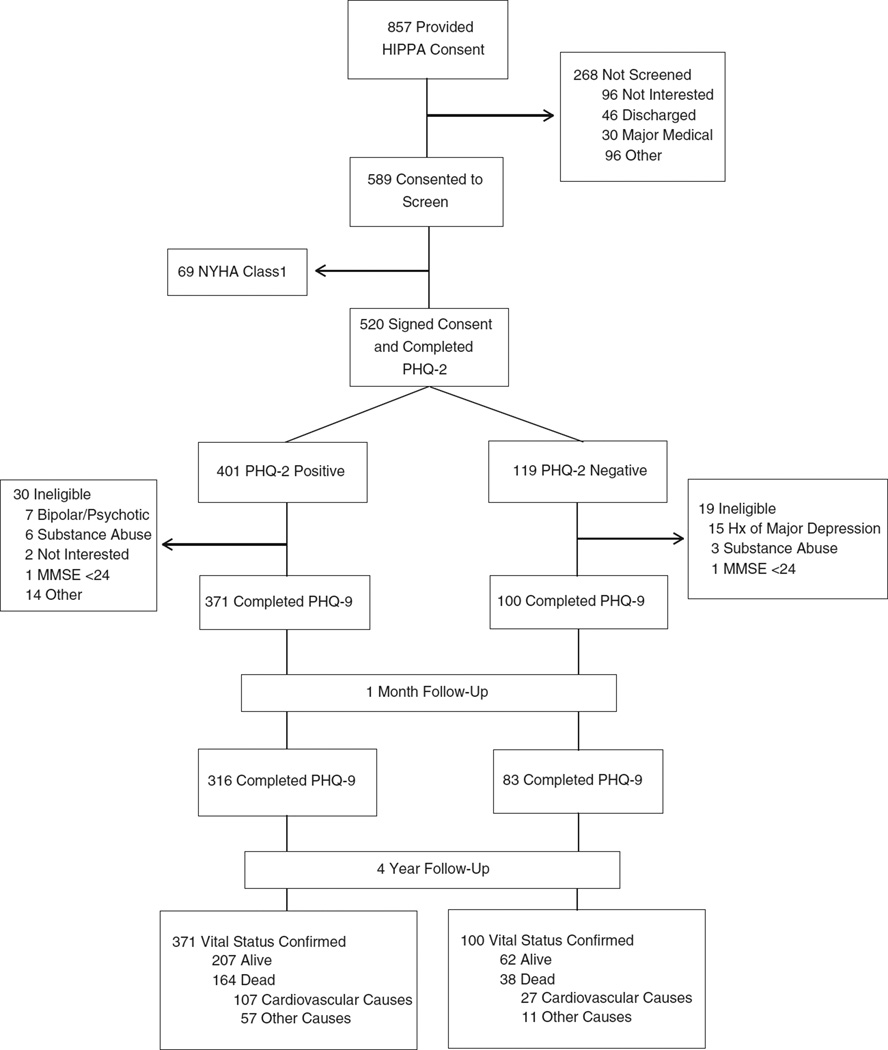

As portrayed in Fig. 1, hospital medical staff identified 857 HF patients with HF who provided HIPAA consent for one of our nurse-recruiters to approach. Of these, 589 (69%) agreed to undergo our screening procedure, and 69 were ineligible as they reported NYHA class I symptoms. Of the remaining 520 who provided signed informed consent and completed the PHQ-2, 401 were PHQ-2 (+) and 119 PHQ-2 (−), and 471 met all protocol eligibility criteria and completed the PHQ-9 [371 PHQ-2 (+) and 100 PHQ-2 (−)]. Later, 316 PHQ-2 (+) and 83 PHQ-2 (−) study subjects completed the 1-month follow-up PHQ-9 by telephone, and we confirmed vital status on all 471 (100%) at 4 years following enrollment of the last recruited patient (June 2013). Afterwards, we identified 202 deaths [164 PHQ-2 (+) and 38 PHQ-2 (−); 43%] and were able to categorize a cause of death on 194 (96%), of which we classified 134 (69%) as cardiovascular-related.

Fig. 1.

Study recruitment and 4-year follow-up. Abbreviations: PHQ-2, two-item Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-9, nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire. †We targeted recruitment of 372 PHQ-2 (+) patients and purposely oversampled PHQ-2 (+) patients by concluding recruitment of PHQ-2 (−) patients after we reached our planned goal of 100 patients.

3.2. Baseline patient characteristics

Compared with HF patients who screened PHQ-2 (−) at baseline, PHQ-2 (+) patients were younger and more likely to have comorbid anxiety, report more depressive and NYHA functional class symptoms and have lower levels of physical and mental health-related quality of life but otherwise had similar sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics by inpatient PHQ-2 status

| PHQ-2 (+) (N=371) |

PHQ-2 (−) (N=100) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) range | 65 (13.4) 23–91 | 70 (11.4) 37–93 | <.01 |

| Male (N) | 64% (237) | 67% (67) | .56 |

| Caucasian (N) | 85% (315) | 86% (86) | .79 |

| NYHA class (N)a | 33% (123) | 61% (61) | |

| II | 39% (146) | 32% (32) | |

| III | 28% (103) | 7% (7) | |

| IV | <.01 | ||

| Ejection fraction, % (SD) | 25.8 (7.8) | 25.3 (7.1) | .51 |

| Myocardial infarction (N) | 51% (189) | 58% (58) | .25 |

| Post-CABG surgery (N) | 42% (158) | 41% (41) | .78 |

| Diabetic (N) | 42% (156) | 38% (38) | .47 |

| COPD (N) | 27% (101) | 25% (25) | .66 |

| Renal insufficiency (N)b | 25% (94) | 24% (24) | .78 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl, mean (SD) | 12.6 (2.1) | 12.7 (1.9) | .72 |

| Sodium, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 138.6 (3.8) | 139.0 (4.0) | .38 |

| ACE-I or ARB use (N) | 74% (275) | 67% (67) | .16 |

| Beta-blocker use (N) | 83% (307) | 79% (79) | .39 |

| Coumadin use (N) | 37% (139) | 48% (48) | .06 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg, mean (SD) | 134.2 (68.9) | 145.4 (124.7) | .39 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 78.9 (70.3) | 93.1 (131.2) | .30 |

| SF-12 MCSa | 44.4 (11.3) | 58.5 (6.8) | <.01 |

| SF-12 PCSa | 30.7 (9.2) | 34.3 (10.6) | <.01 |

| Anxiety disorder (N)a | 30% (110) | 1% (1) | <.01 |

| PHQ-9, mean (SD)a | 11.3 (4.5) | 3.5 (2.4) | <.01 |

| PHQ-9 (N)a | |||

| 0–4 | 5% (20) | 72% (72) | |

| 5–9 | 32% (119) | 27% (27) | <.01 |

| 10–14 | 36% (135) | 1% (1) | |

| 15+ | 26% (97) | 0% (0) | |

| Antidepressant use (N)c | 26% (97) | — | – |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive lung disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12 MCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Mental Component Scale; SF-12 PCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Physical Component Scale.

Differences by PHQ-2 status remained significant after controlling for multiple comparisons.

Renal Insufficiency defined as creatinine>1.7 mg/dl.

Antidepressant use at baseline was an exclusion criterion for inclusion in the PHQ-2 (−) study cohort. However, no PHQ-2 (−) patients were excluded for this reason.

3.3. Impact of a positive inpatient PHQ-2 screen on mortality

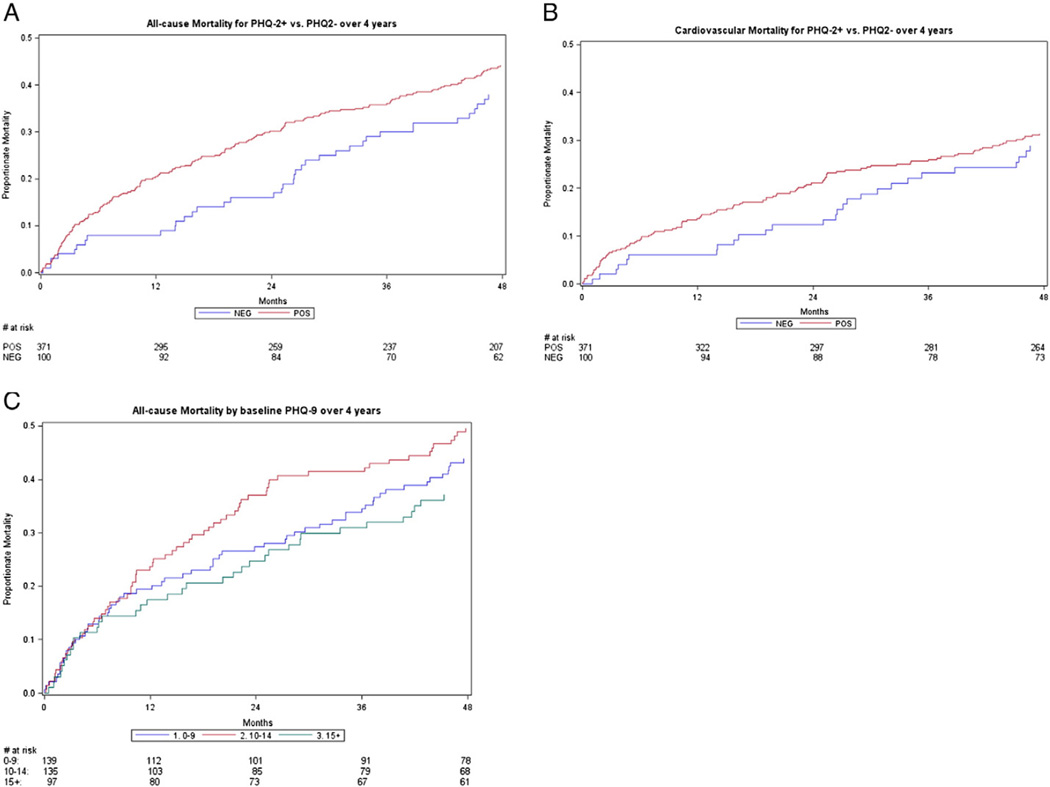

A positive inpatient PHQ-2 screen for depressive symptoms was predictive of increased univariate all-cause [30% vs. 16% (P<.01)] and cardiovascular mortality [20% vs. 12% (P=.05)] for up to 2 years following the index hospitalization (Supplementary Table 1 in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.06.005). After adjustment for age, gender, LVEF and other known predictors of HF mortality, the increased risk of a positive PHQ-2 depression screen on all-cause mortality persisted to 4 years of follow-up [HR: 1.50 (1.02–2.20); P=.04] (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1 in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.06.005); however, PHQ-2 status remained predictive of increased cardiovascular mortality to only 2 years of follow-up (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1 in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016. 06.005). Sensitivity analyses that assigned a cardiovascular death to the 8 patients for whom we were unable to establish a cause of death or excluded the 97 PHQ-2 (+) patients using antidepressant pharmacotherapy at baseline did not alter our findings. Finally, a positive response to either or both PHQ-2 items conferred a similar mortality risk (incidence of mortality at 4 years of follow-up: 44% for “yes” to “little interest or pleasure in doing things”; 45% for “yes” to “feeling down, depressed or hopeless”; 45% for an affirmative response to both items).

Table 2.

Adjusted models of 4-year all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

| All-Cause Mortality | Cardiovascular Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| PHQ-2 (+) vs. PHQ-2 (−) | 1.50 (1.02–2.20) | .04 | 1.44 (0.91–2.29) | .12 |

| Female vs. male gender | 1.18 (0.88–1.58) | .28 | 1.22 (0.85–1.75) | .28 |

| Age (≥65 vs. <65 years old) | 2.40 (1.73–3.34) | <.01 | 2.36 (1.57–3.54) | <.01 |

| LVEF (≤30% vs. >30%) | 1.19 (0.86–1.65) | .30 | 1.34 (0.89–2.04) | .16 |

| NYHA class (III–IV vs. II) | 1.35 (0.98–1.86) | .06 | 1.17 (0.80–1.72) | .42 |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.84 (0.58–1.21) | .34 | 0.95 (0.61–1.49) | .83 |

| COPD | 1.42 (1.05–1.93) | .02 | 1.34 (0.92–1.96) | .12 |

| Renal insufficiency | 2.07 (1.52–2.81) | <.01 | 1.90 (1.30–2.78) | <.01 |

| ACE-I or ARB | 0.90 (0.65–1.23) | .49 | 0.74 (0.51–1.08) | .12 |

| Beta-blocker | 0.76 (0.53–1.09) | .13 | 0.83 (0.53–1.29) | .40 |

| Coumadin | 1.10 (0.82–1.47) | .52 | 1.17 (0.82–1.68) | .38 |

| Diabetes | 1.50 (1.13–2.00) | <.01 | 1.75 (1.23–2.48) | <.01 |

| Hemoglobin (<10 vs. ≥ 10 g/dl) | 1.55 (1.02–2.36) | .04 | 1.35 (0.79–2.31) | .27 |

| Sodium (<136 vs. ≥136 mmol/L) | 1.01 (0.69–1.46) | .98 | 0.96 (0.60–1.53) | .86 |

| Diastolic BP (per 10-unit increase) | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | .38 | 1.05 (0.98–1.14) | .18 |

| Systolic BP (per 10-unit increase) | 0.97 (0.91–1.04) | .38 | 0.95 (0.88–1.03) | .21 |

Abbreviations: ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive lung disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; SF-12 MCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Mental Component Scale; SF-12 PCS, Medical Outcomes Study Short Form Physical Component Scale.

Fig. 2.

4-Year all-cause and cardiovascular mortality by baseline PHQ status. (A) All-cause mortality by PHQ-2 status. By 4-year follow-up, 44% of PHQ-2 (+) and 38% of PHQ-2 (−) patients had died (P=.16). (B) Cardiovascular mortality by PHQ-2 status. By 4-year follow-up, 29% of PHQ-2 (+) and 27% of PHQ-2 (−) patients had died of a cardiovascular cause (P=.44). (C) All-cause mortality by baseline PHQ-9 level among 371 PHQ-2 (+) patients. By 4-year follow-up, 44%, 50% and 37% of HF patients with PHQ-9 score levels 0–9, 10–14 and ≥15, respectively had died (P=.17). Abbreviations: PHQ-2 (+), positive Patient Health Qustionnaire-2 screen for depression; PHQ-2 (−), negative Patient Health Qustionnaire-2 screen for depression.

3.4. Timing of the follow-up PHQ-9 to PHQ-2 screen-positive patients

At 1-month telephone follow-up, 85% (316/371) PHQ-2 (+) patients completed the PHQ-9, 12% (47) declined or were unable to complete their follow-up and 3 (8%) had died. Compared to those PHQ-2 (+) patients who completed their follow-up assessment, the 55 PHQ-2 (+) patients who did not tended to be younger (65 vs. 69 years; P= .05) but were otherwise similar on baseline PHQ-9 score and other sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (data not shown).

Compared to the inpatient PHQ-9, both the mean PHQ-9 score and proportion of those who reported a score ≥10 declined when reassessed at 1-month follow-up (63% vs. 24%; P<.001) (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, just 7 (6%) PHQ-2 (+) patients who scored 9 or less on their inpatient PHQ-9 scored ≥10 a month later, and no PHQ-2 (−) patient scored ≥10 on their 1-month follow-up PHQ-9.

Neither the inpatient nor 1-month follow-up PHQ-9 provided any additional prognostic information on 4-year mortality over the inpatient PHQ-2 screen after adjustment for potentially confounding variables [all-cause mortality: PHQ-2 (+ vs. −): HR 1.5 (P=.04) and PHQ-9 (≥10 vs. <10): 1.07 (P=.70) and cardiovascular mortality PHQ-2 (+ vs. −): HR 1.4 (P=.12) and PHQ-9 (≥10 vs. <10): 0.81 (P=.31)]. Lastly, we did not observe a dose effect of PHQ-9 score level on mortality risk (Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

Among hospitalized patients with systolic HF, a positive PHQ-2 screen for depressive symptoms was predictive of a significantly elevated risk of all-cause mortality risk for up to 4 years postdischarge independent of disease severity and other factors associated with HF mortality. Furthermore, while administering the PHQ-9 immediately following a positive inpatient PHQ-2 screen generated a higher prevalence of depression compared to administering the follow-up PHQ-9 a month later, the level of PHQ-9 score did not provide any additional prognostic information on mortality beyond the PHQ-2 screen, and no patient who screened negative for depressive symptoms on the inpatient PHQ-2 later scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 administered 1 month following hospital discharge.

Our findings are consistent with prior reports and those that used more complex and time-consuming measures to screen for depression [2,19–22]. Moreover, they are supported by our ability to confirm vital status on 100% of our study cohort and adjust for a variety of established risk factors for HF mortality. To increase the utility and generalizability of our findings, we dichotomized respondents' replies on each item of the PHQ-2 rather than use the full Likert scale range as we believe that the screen is more likely to be utilized in this manner by busy staff in routine clinical practice settings. Finally, while we found the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 to be comparable in their ability to identify hospitalized HF patients at increased risk for mortality as others have reported [23], we did not find a similar dose–response in the relationship between depressive symptoms and mortality risk in contrast to other studies [23–26].

4.1. Optimal timing to administer the PHQ-9

The majority of hospitalized PHQ-2 (+) HF patients scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 administered during hospitalization signifying an at least moderate level of depressive symptoms. However, just one fourth of these patients met this threshold when the PHQ-9 was administered 1 month following discharge. This supports the concern that the PHQ-9 may overlap with common symptoms experienced by hospitalized HF patients with depressive symptoms (e.g., fatigue, appetite, sleep disturbances), and/or many true depressive symptoms may spontaneously resolve once patients return to their home environment.

Our findings support a delay in administration of the follow-up PHQ-9 to PHQ-2 (+) HF patients until after discharge so as to avoid possible overdiagnosis and overtreatment for depressive symptoms. However, we recognize that this may have the unintended effect of delaying the potential start of effective treatment and relief of suffering. Moreover, our finding that no hospitalized PHQ-2 (−) HF patient later scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 administered 1 month later indicates that these patients do not require formal rescreening for depression soon after hospitalization. Finally, while the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 have similar predictive value for mortality, pragmatically, we consider the PHQ-2 as the better screening instrument to utilize in routine clinical practice due to its lower respondent burden and being far easier for busy clinicians to remember and administer than PHQ-9.

Although it remains to be determined whether screening and treating HF patients for depressive symptoms reduces mortality [27–30], randomized trials in patients with cardiovascular disease clearly demonstrate that effective treatment for depression can improve quality of life [31–33] and speed recovery [31,33] and can reduce health care costs [34,35] as well as depressive symptoms [31–34,36]. Although few of these studies specifically addressed patients with HF [28,30,32,36], we nevertheless recommend hospitals and health care systems screen all hospitalized HF patients with the PHQ-2 to identify those at elevated mortality risk who may benefit from their clinicians' extra attention and that the follow-up PHQ-9 be administered to all PHQ-2 screen-positive patients either (a) immediately following the PHQ-2 when the patient has a history of depression or (b) within 1 month following hospital discharge when the patient has no prior history. Finally, in accordance with the AHA Science Advisory [5] and our prior work [37], we recommend starting depression treatment as guided by a careful evaluation that includes consideration of the patient's past history of and treatment for depression, preference for current care and PHQ-9 score.

4.2. Limitations

We designed our study to inform the later development of an effectiveness trial for treating depression in patients with systolic HF, not as an epidemiologic survey to systematically screen all hospitalized patients to determine the prevalence of depression among hospitalized patients with HF. Therefore, we purposely oversampled PHQ-2 (+) patients and limited recruitment of PHQ-2 (−) subjects. Still, PHQ-2 (+) and PHQ-2 (−) patients were similar by most baseline sociodemographic and clinical measures, and we adjusted our results for a variety of potential confounders [15,16] and conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. Second, although it is presently unclear whether depression treatment reduces the incidence of mortality, we lacked information on the 4-year course and treatment of depressive symptoms and on any treatment the patient received for their HF that could have affected their mortality risk (e.g., implantation of a cardiac defibrillator). Third, study patients may have changed their behaviors that diminished the long-term impact of depression on mortality (e.g., quit smoking). Finally, the generalizability of our results may be limited given the predominantly male and white cohort recruited in one region of the United States.

5. Conclusions

A positive PHQ-2 screen for depressive symptoms among hospitalized patients with systolic HF is an independent risk factor for increased all-cause mortality for up to 4 years following the index hospitalization. While it is presently unknown whether effective treatment of depression in patients with systolic HF will reduce mortality risk, our findings extend the AHA's Science Advisory that recommends increased awareness, screening and treatment of depression in patients with coronary heart disease to hospitalized patients with systolic HF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded through a grant from the National Institutes of Health awarded to …… and through a training grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation that supported Dr. ……'s efforts.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.06.005.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics — 2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutledge T, Reis VA, Linke SE, Greenberg BH, Mills PJ. Depression in heart failure a meta-analytic review of prevalence, intervention effects, and associations with clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fan H, Yu W, Zhang Q, Cao H, Li J, Wang J, et al. Depression after heart failure and risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2014;63:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson TJ, Basu S, Pisani BA, Avery EF, Mendez JC, Calvin JE, Jr, et al. Depression predicts repeated heart failure hospitalizations. J Card Fail. 2012;18:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtman JH, Bigger JT, Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lesperance F, et al. Depression and coronary heart disease: recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Prevention Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Psychiatric Association. Circulation. 2008;118:1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW. Effect of depression on prognosis in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2011;7:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollman BL, Herbeck Belnap B, Mazumdar S, Houck P, McNamara DM, Alvarez RJ, et al. A positive depression screen among hospitalized heart failure patients is associated with elevated 12-month mortality. J Cardiac Fail. 2012;18:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havranek EP, Spertus JA, Masoudi FA, Jones PG, Rumsfeld JS. Predictors of the onset of depressive symptoms in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2333–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF:12 how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of the PRIME-MD. The PHQ Primary Care Study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elderon L, Smolderen KG, Na B, Whooley MA. Accuracy and prognostic value of American Heart Association: recommended depression screening in patients with coronary heart disease: data from the heart and soul study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:533–540. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.960302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochberg Y, Benjamini Y. More powerful procedures for multiple significance testing. Stat Med. 1990;9:811–818. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, Liu PP, Naimark D, Tu JV. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pocock SJ, Wang D, Pfeffer MA, Yusuf S, McMurray JJV, Swedberg KB, et al. Predictors of mortality and morbidity in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:65–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fosbol EL, Gislason GH, Poulsen HE, Hansen ML, Folke F, Schramm TK, et al. Prognosis in heart failure and the value of {beta}-blockers are altered by the use of antidepressants and depend on the type of antidepressants used. Circulation. 2009;2:582–590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.851246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Freedland KE, Youngblood M, Veith RC, Burg MM, et al. Depression and late mortality after myocardial infarction in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:466–474. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000133362.75075.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, et al. Relationship between depressive symptoms and long-term mortality in patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celano CM, Suarez L, Mastromauro C, Januzzi JL, Huffman JC. Feasibility and utility of screening for depression and anxiety disorders in patients with cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:498–504. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adams J, Kuchibhatla M, Christopher EJ, Alexander JD, Clary GL, Cuffe MS, et al. Association of depression and survival in patients with chronic heart failure over 12 years. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:339–346. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang W, Krishnan R, Kuchibhatla M, Cuffe MS, Martsberger C, Arias RM, et al. Characteristics of depression remission and its relation with cardiovascular outcome among patients with chronic heart failure (from the SADHART-CHF Study) Am Cardiol. 2011;107:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piepenburg SM, Faller H, Gelbrich G, Stork S, Warrings B, Ertl G, et al. Comparative potential of the 2-item versus the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire to predict death or rehospitalization in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:464–472. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.114.001488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, Kuchibhatla M, Gaulden LH, Cuffe MS, et al. Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1849–1856. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.15.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F, Habra M, Talajic M, Khairy P, Dorian P, et al. Elevated depression symptoms predict long-term cardiovascular mortality in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:134–140. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851675. [3p following 140]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Junger J, Schellberg D, Muller-Tasch T, Raupp G, Zugck C, Haunstetter A, et al. Depression increasingly predicts mortality in the course of congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thombs BD, Roseman M, Coyne JC, de Jonge P, Delisle VC, Arthurs E, et al. Does evidence support the American Heart Association's recommendation to screen patients for depression in cardiovascular care? An updated systematic review. PLoS One. 2013:e52654. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor CM, Jiang W, Kuchibhatla M, Silva SG, Cuffe MS, Callwood DD, et al. Safety and efficacy of sertraline for depression in patients with heart failure: results of the SADHART-CHF (Sertraline Against Depression and Heart Disease in Chronic Heart Failure) Trial. JACC. 2010;56:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woltz PC, Chapa DW, Friedmann E, Son H, Akintade B, Thomas SA. Effects of interventions on depression in heart failure: a systematic review. Heart Lung. 2012:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Stork S, Fallgatter A, Deckert J, Faller H, et al. Rationale and design of a randomised, controlled, multicenter trial investigating the effects of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibition on morbidity, mortality and mood in depressed heart failure patients (MOOD-HF) Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:1212–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Counihan PJ, et al. Telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:2095–2103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freedland KE, Carney RM, Rich MW, Steinmeyer BC, Rubin EH. Cognitive behavior therapy for depression and self-care in heart failure patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1773–1782. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.5220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huffman JC, Mastromauro CA, Beach SR, Celano CM, DuBois CM, Healy BC, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety disorders in patients with recent cardiac events: the Management of Sadness and Anxiety in Cardiology (MOSAIC) randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:927–935. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davidson KW, Bigger JT, Burg MM, Carney RM, Chaplin WF, Czajkowski S, et al. Centralized, stepped, patient preference-based treatment for patients with post-acute coronary syndrome depression: CODIACS vanguard randomized controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:997–1004. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O'Connor C, Keteyian S, Landzberg J, Howlett J, et al. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:465–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O'Connor C, Keteyian S, Landzberg J, Howlett J, et al. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:465–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rollman BL, Belnap Herbeck B, Lemenager M, Mazumdar S, Schulberg HC, F C. Reynolds III The Bypassing the Blues treatment protocol: stepped collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:217–230. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181970c1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.