Abstract

This review highlights state-of-the-art procedures for heterologous small-molecule biosynthesis, the associated bottlenecks, and new strategies that have the potential to accelerate future accomplishments in metabolic engineering. We emphasize that a combination of different approaches over multiple time and size scales must be considered for successful pathway engineering in a heterologous host. We have classified these optimization procedures based on the “system” that is being manipulated: transcriptome, translatome, proteome, or reactome. By bridging multiple disciplines, including molecular biology, biochemistry, biophysics, and computational sciences, we can create an integral framework for the discovery and implementation of novel biosynthetic production routes.

Microbial “molecular factories” can produce value-added compounds (e.g., pharmaceuticals). But their development requires the optimization of multiple systems—those of the transcriptome, translatome, proteome, and reactome.

CURRENT APPROACHES IN METABOLIC ENGINEERING AND THEIR LIMITATIONS

Microbial organisms are able to package a set of biocatalysts into “molecular factories” for the energy-efficient generation of value-added compounds derived from simple sugars (Keasling 2010). Making use of these molecular factories is an attractive alternative to organic syntheses that rely on petrochemical feedstocks, finite resources, or environmentally unfriendly production processes. However, microbial organisms have not evolved to meet the demands of a scaled-up production process at the industrial scale and tend to have a poor ratio of achieved versus theoretical yield. Thus, one of the main goals of metabolic engineering is to transform organisms into efficient systems for the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients, commodity chemicals, and energy. Metabolic engineering has already provided sustainable access to a number of chemical classes. A recent milestone of bio-based industrial production is the engineered microbial biosynthesis of artemisinic acid, a plant-derived precursor to the antimalarial drug artemisinin (Paddon et al. 2013). Additional high-value compounds produced via sustainable processes include antibiotics, such as erythromycin A, daptomycin, and penicillin, as well as precursors to pharmaceuticals like taxadien-5a-acetoxy-10b-ol, which are reviewed elsewhere (Lee et al. 2009). Industrial fermentation processes have also been established for production of commodity chemicals like 1,3-propanediol, 1,4-butanediol, farnesene, and other terpenoids (for a review on this topic, see Klein-Marcuschamer et al. 2007). Further progress in metabolic engineering could facilitate industrial biosynthesis of the biofuels isobutanol, isopentenol, bisabolene, and pinene, as well as other hydrocarbons (for a review on this topic, see Lennen and Pfleger 2013). However, some important classes of small molecules, such as alkanes, alkenes, alkaloids, polyketides, and peptides, remain accessible mostly from native sources or through organic synthesis.

Why do we succeed in biomanufacturing certain compound classes while others remain recalcitrant? One limitation is the lack of integrated approaches toward pathway optimization. Most strategies deal with bottlenecks on only one of multiple levels in pathway engineering, often addressing either gene expression or enzyme engineering. This semirational approach is popular because quantitative behavior remains difficult to predict for complex biological systems. Inaccurate predictions in turn are partly a result of unknown or unpredictable cellular behavior most likely caused by additional undefined layers of control. Sometimes this is compounded by limitations in genetic accessibility of the host. Of the many microbial species that have potential as efficient factories, only a small number are currently genetically tractable. The recent discovery of the CRISPR/Cas system has the potential to readily engineer previously intractable species, but this technique has yet to be implemented widely among species (Jakočiūnas et al. 2015). In all cases, metabolic engineering is limited by analytical methods, which require specific method optimization for each compound class being produced. Despite these shortcomings, there are clear advancements in the development of new -omics data acquisition and analysis techniques that enable metabolic engineering on various levels. These challenges and perspectives highlight the need to implement a multilayer optimization framework to perfect the “design–build–test–learn” engineering cycle of synthetic biology.

THE NEED FOR INTEGRATED APPROACHES IN METABOLIC ENGINEERING

The ideal design for maximal metabolite production would generate active enzymes with sufficient catalytic turnover in consideration of timing and cellular location. This is a hard goal to achieve because of the complexity of the cell. Overlaid systems interact at different time scales and a single manipulation may have a positive impact at one metabolic or regulatory layer and a negative or neutral impact at another. Modifications at the transcriptome level adjust the timing and strength of gene expression, whereas changes to the translatome (measured by ribosome occupancy) influence protein synthesis rates, local translational speed, as well as protein solubility, activity, and specificity. Changes to the sequence and structure of proteins affect the catalytic efficiency of pathway enzymes and allosteric regulation at the proteome level. At the reactome level, balanced enzyme activity, sufficient transfer of intermediates between enzymes, and cofactor balance are all required for high flux through the engineered pathway.

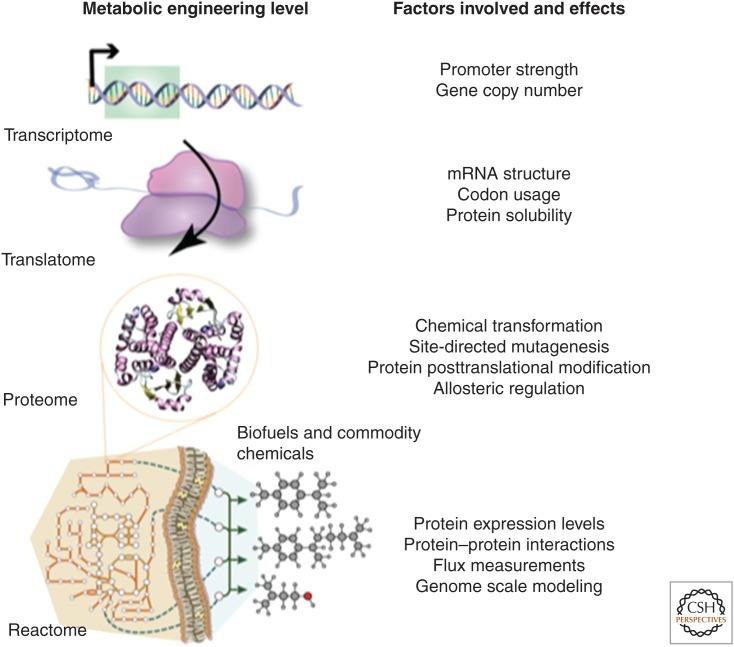

A multilevel engineering approach can be subdivided into manageable processes (Fig. 1). At the transcriptome level, mRNA amounts are controlled by promoter strength, gene copy number, and mRNA stability. At the translatome level, translational efficiency and protein solubility are tuned by ribosome-binding site (RBS) strength, mRNA secondary structure, and codon usage. At the protein/proteome level, efficient catalysis is engineered by site-specific enzyme modifications and release of feedback inhibition. At the reactome level, enzyme ratio balancing and protein colocalization affect the efficient turnover of pathway intermediates. Robust and optimal calibration of all of these nested and interlocked mechanisms is necessary to achieve maximum flux through an engineered pathway. We propose a multilayer framework for metabolic engineering by integrating design and control elements on multiple levels to accelerate the implementation and optimization of novel biosynthetic production routes.

Figure 1.

Integrated approaches in metabolic engineering. To achieve high metabolite flux through a biosynthetic pathway, it is essential to consider bottlenecks on the transcriptome, translatome, protein/proteome, and reactome level. Integrated metabolic engineering approaches need to occur both on the molecular-scale and system-scale level.

ENGINEERING AT THE TRANSCRIPTOME AND TRANSLATOME LEVEL

The most straightforward way to achieve a desired gene expression profile is to regulate the transcription and translation processes, which span a wide dynamic range (102–105-fold) for mRNA and protein amounts (Salis et al. 2009; Blazeck et al. 2012). Metabolic engineers would like to temporally regulate the expression strength of nonnative genes to minimize the metabolic burden of protein synthesis because nonoptimal expression may draw cellular resources away from essential functions and lower the overall fitness of the host (Poelwijk et al. 2011). This, in turn, can lead to decreased pathway productivity, reducing the design space at the reactome and proteome levels. Synthetic biology efforts have provided characterized native and synthetic promoters to control mRNA expression levels (Leavitt and Alper 2015). However, our ability to forward engineer heterologous gene expression with a precise outcome regarding protein amounts and activity is currently lacking (Figs. 2 and 3). To avoid unnecessary rounds of expression optimization, it is advisable to identify common bottlenecks that can be bypassed in advance. We will discuss a few studies that have addressed these issues and suggest an improved workflow.

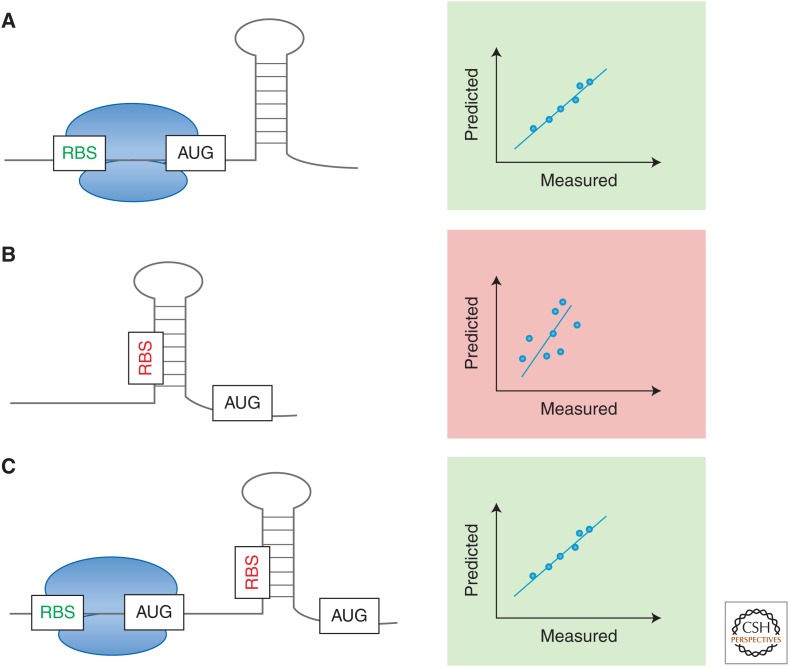

Figure 2.

Predictable and reliable gene expression. (A) To precisely predict translation initiation rates, the ideal transcript would be depleted in secondary structures close to the ribosome-binding site (RBS). However, mRNA secondary structures are crucial to overall transcript stability and translation speed control. (B) Secondary structures present in most nascent mRNA molecules complicate accurate computational predictions of expression strength. Depending on the location of the hairpin, secondary structure formation can slow down translation initiation rates or completely prevent translation initiation in case of an occluded RBS. (C) The bicistronic gene design developed by Mutalik and coworkers (Davis et al. 2011; Mutalik et al. 2013) allows for higher predictability, because a constant short open reading frame is placed upstream of the target expression cassette that allows for read-through despite the presence of downstream hairpins.

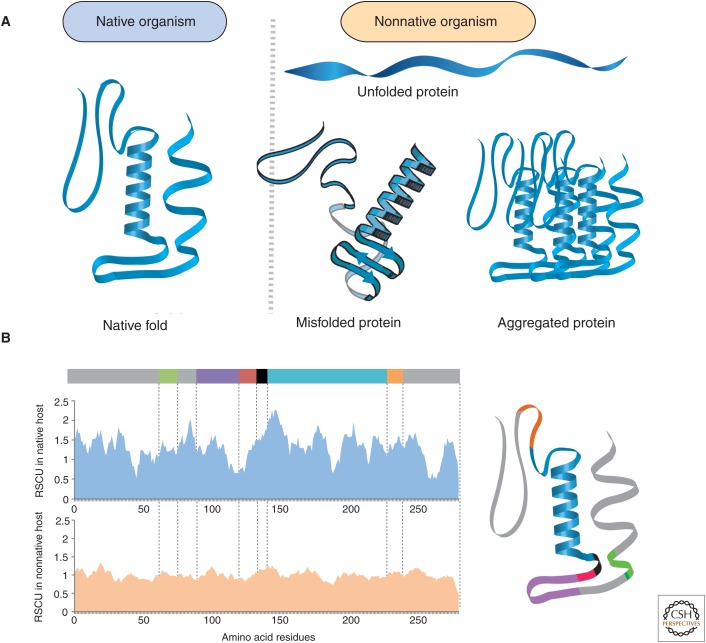

Figure 3.

Soluble and active protein biosynthesis. (A) Proteins expressed in their native host naturally assume a soluble and catalytically active tertiary structure, whereas protein synthesis in nonnative hosts leads to misfolded or aggregated proteins. (B) Relative synonymous codon usage plots (RSCUs) for a representative protein in native and nonnative hosts correlated with structural motifs within the protein.

Predictable and Reliable Gene Expression

It is well known that mRNA and protein levels do not perfectly correlate in native or engineered systems (Jayapal et al. 2008; Vogel and Marcotte 2012; Payne 2015). This variation is especially prevalent in prokaryotic expression, but remained unaccounted for in genetic design principles until recently. Synthetic biology is striving to establish a knowledge base for modular expression design based on a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between mRNA sequence and protein abundance. Toward this goal, Kosuri et al. (2013) analyzed a library of >12,500 promoter and RBS combinations in Escherichia coli. As a result of this study, a short list of part combinations was created to guide future expression constructs with desired mRNA and protein level profiles. However, when predictions and measurements were compared in this study, the correlation was much lower for protein abundance (R2 = 0.82) than for mRNA abundance (R2 = 0.96). A small fraction of constructs displayed an even greater discrepancy, which indicates the presence of unknown variables in this combinatorial design. One significant contributor to the context-dependent variation is sequence-dependent mRNA secondary structure formation around the translation start site, which greatly influences synthesized protein amounts and complicates accurate predictions (Fig. 2).

To close the gap between designed and tested gene-expression patterns, Mutalik et al. created a new bicistronic expression cassette in combination with a previously reported insulated promoter design (Davis et al. 2011; Mutalik et al. 2013). In this design, the RBS initiating translation of the reporter gene was embedded within an upstream open reading frame for a short leader peptide (Fig. 2). The investigators suggest that the intrinsic helicase activity of the translation machinery is able to unwind any secondary structures present in the target RBS when reading through the upstream gene. Testing a library of promoter and RBS combination arranged as part of the bicistronic design, the investigators were able to significantly reduce the error rate in forward engineering. The bicistronic design had a correlation rate of 93% within a twofold window of expected expression levels compared with 84% for the monocistronic design. This allowed the characterization of >500 composable parts over a wide dynamic transcription and translation range to enable predictable engineering in E. coli.

The existence of context-dependency has also been described for eukaryotic gene expression. Dvir et al. (2013) measured a sevenfold change in protein abundance when manipulating a very small nucleotide sequence space surrounding the RBS of a reporter gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Based on these measurements, a quantitative model was developed to correctly predict 74% of the protein levels considering a list of factors (i.e., mRNA secondary structure, in-frame and out-of-frame start codons, predicted nucleosome occupancy, sequence composition statistics, and arbitrary k-mer sequences). Translation efficiency has also been correlated with mRNA secondary structure formation in the 5′ coding region (Cannarozzi et al. 2010; Tuller et al. 2010; Goodman et al. 2013). Importantly, these studies imply that protein synthesis rates are affected by noncoding and coding sequences in a context-dependent manner, which may be disentangled using computational approaches. Finally, to test protein-specific influences on translation efficiency and to drive these predictions toward general design guidelines for expression of all types of protein classes, additional studies with proteins other than fluorescence reporters are required. Additional and unknown layers of transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational control remain to be identified.

Soluble and Active Protein Biosynthesis

The successful implementation of a heterologous pathway also requires the production of functional enzymes, whereas suboptimal translation of mRNA into misfolded proteins can lead to low catalytic turnover (reviewed in Li 2015). The use of enzymes from hosts that are distantly related to the expression host is one well-known stumbling block for expression of catalytically active proteins (Fig. 3). Certain bottlenecks in heterologous expression can be attributed to intrinsic host factors, such as translation speed, tRNA abundance, and chaperones. For example, tRNA abundance and codon usage bias is known to vary between and even within organisms depending on the growth stage (Ikemura 1985; Dong et al. 1996; Kanaya et al. 1999). Different temporal factors in recombinant protein expression are important, from the growth stage of the host organism to the initiation and elongation rate of nascent peptide chains (Nissley and O’Brien 2014). Changing expression timing and translation rates can affect not only translational efficiency but also important protein properties, such as solubility, activity, and specificity (Plotkin and Kudla 2011; Hunt et al. 2014). Other bottlenecks arise from the gene coding sequence itself, such as mRNA folding, transcript length, type of encoded amino acids, codon context, and codon usage.

The most influential factor affecting translational efficiency in bacterial expression is believed to be codon usage bias (Lithwick and Margalit 2003). This notion is an essential motivation for the common use of codon-adjusted transgenes (Gustafsson et al. 2004; Gould et al. 2014). However, synonymous codon changes pose the potential risk of disrupting important characteristics of a nucleotide sequence, such as mRNA stability and translation rates. It comes as no surprise that idiosyncratic reports reveal a poor correlation between codon “optimization” and functional protein levels. There are a myriad of variables affecting translation, such as mRNA stability, translation speed and accuracy, cotranslational folding, and cotranslational localization. However, the influence of these factors in distinct organisms or even protein families might vary. For instance, transgenic expression in eukaryotic systems is burdened by gene-silencing issues or low expression levels (Jackson et al. 2014). On the other hand, bacterial host systems are known to commonly produce misfolded proteins (Sander et al. 2014). There is a great need for synthetic codon adaptation strategies that consider multiple prevailing design parameters in a host- and time-dependent manner.

Recently, Lanza et al. (2014) created a condition-specific codon optimization approach, which considers the dynamic character of protein translation. The investigators generated a codon usage table based on a subset of highly expressed genes at the target growth stage and were able to improve heterologous protein levels of a bacterial gene in yeast. Other studies have used combinatorial libraries with synonymous codon variants in the coding region to experimentally disentangle the factors involved in translational efficiency and protein integrity (Goodman et al. 2013; Cheong et al. 2015). Such studies have established that synonymous codons are translated at different rates affecting cotranslational folding (Ciryam et al. 2013; Chevance et al. 2014) and localization (Fig. 3) (Fluman et al. 2014; Pechmann et al. 2014). In summary, we emphasize that the interrelation between codon usage, cotranslational folding, and protein integrity can greatly affect the catalytic activity of heterologous proteins (Kimchi-Sarfaty et al. 2007; Agashe et al. 2013; Zhou et al. 2013).

ENGINEERING AT THE PROTEIN LEVEL

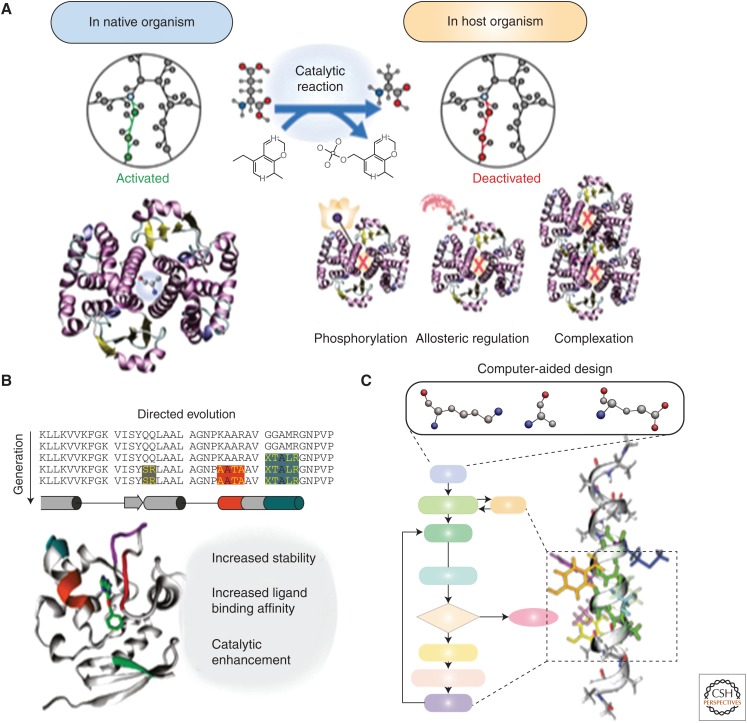

Increasing yields of desired compounds can further be influenced by the capacity of the proteins themselves to catalyze a desired reaction. Native and nonnative enzymes commonly require further optimization to meet the demands of biomanufacturing (Fig. 4). Recent advances in enzyme engineering bring about significant expansions in the catalytic repertoire of enzymes with respect to increased efficiencies, improved selectivities, and novel substrate and cofactor specificities. In addition, the de novo engineering of enzymes has enabled the design of novel catalysts in which natural enzymes are not available (Bolon et al. 2002; Kaplan and DeGrado 2004; Jiang et al. 2008; Röthlisberger et al. 2008). Numerous engineering strategies have been developed to tailor enzyme activities for specific industrial purposes, which include directed evolution and mutagenesis (Moore and Arnold 1996; Arnold 1998; Brustad and Arnold 2011; Illanes et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012b), modular enzyme components (Dueber et al. 2009; Good et al. 2011), and computer-aided design techniques (Bornscheuer and Pohl 2001; Mandell and Kortemme 2009; Verma et al. 2012; Hilvert 2013; Damborsky and Brezovsky 2014) (for a recent review of the impact of directed evolution on synthetic biology, see Currin et al. 2015). The enzymatic characteristics that are most often targeted by these techniques include activity, stability, selectivity, solubility, and optimal pH (Fig. 4). For example, engineered fungal endoglucanases operate at optimal temperatures of 17°C higher than the wild-type enzyme and hydrolyze 1.5 times as much cellulose over 60 h (Trudeau et al. 2014). Engineering stable enzymes such as these has benefited the production of isobutanol at elevated temperatures in thermophilic Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius (Lin et al. 2014). However, in contrast to the numerous successful accounts of directly evolved single enzyme catalysts, limited examples exist for directly evolved enzymes that exist as catalysts within a biosynthetic pathway. In general, this can be explained by the fact that a coordinated improvement of performance of an entire pathway of enzymes has typically not been discovered through the optimization of a single gene.

Figure 4.

Proteome-level optimization. (A) Optimal versus nonoptimal enzyme-level activities in engineered designs. Nonoptimal factors that influence activities may include allosteric regulation, protein posttranslational modifications, incorrect protein–protein interactions, and many others. (B) Graphical representation of directed evolution of enzyme that directly influences its stability and reactivity. (Adapted from Mollwitz et al. 2012.) (C) An in silico workflow to establish rational engineering through novel complementary computational methods, such as machine learning, genetic algorithms, and molecular modeling.

The complexity of pathway design oftentimes requires overcoming metabolic bottlenecks, such as accumulation of toxic intermediates, cofactor imbalance, and inefficient enzyme activities, which remains a significant challenge for metabolic engineering and the focus of numerous research studies (Fig. 4). Metabolic engineering has traditionally integrated existing enzymes from different organisms into the production host to modify an existing pathway or create a nonnatural pathway (e.g., a set of enzymes that are not normally found within the host metabolism). This approach has generated significant improvements in product yields. For example, a 120% yield improvement was reported for the isoprenoid-derived sesquiterpene, amorphadiene, which was produced by an engineered strain of E. coli using the seven-gene mevalonate pathway from S. cerevisiae (Ma et al. 2011). However, the catalytic efficiencies and selectivities of many naturally occurring enzymes may require further optimization to become highly optimized biocatalysts with capacities to achieve higher rates, yields, and product purities. This section reviews the efficiency of the individual enzyme components themselves within existing or nonnatural biosynthetic pathways and poses the following question: “Can engineering individual enzymes transform and improve the performance of biosynthetic routes?” Here, we focus on several successful examples, in which engineered characteristics of individual enzymes did improve the efficiency of entire biosynthetic pathways. The engineered characteristic enzyme properties that are highlighted in this section include enzyme regulation and enzyme specificity.

Reduced Feedback Inhibition

Heterologous proteins expressed in host organisms can suffer from a number of design issues, which include being tightly regulated via posttranslational modifications and/or allosteric inhibition (Fig. 4). In cases such as these, directed evolution of key enzymes within metabolic pathways has shown to benefit product yields (Lee et al. 2012; Brinkmann-Chen et al. 2013) (for reviews on these topics, see Johannes and Zhao 2006; Cobb et al. 2013; Renata et al. 2015). For example, an improved variant of glucosamine synthase (GlmS) was generated via an error-prone polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and its overexpression in an engineered strain of E. coli led production of glucosamine at 17 GL−1 (Deng et al. 2005). The directed evolution of GlmS enabled increased production, in part, by generating variants that showed significantly reduced sensitivity to product inhibition (Deng et al. 2005). Another example of enzyme engineering that reduced feedback-inhibition mechanisms is that of l-phenylalanine production. By performing DNA shuffling on pheA, a chorismate mutase-prephenate dehydratase enzyme, mutations led to activation of enzymatic activities at low phenylalanine concentrations and nearly complete resistance to feedback inhibition of prephenate dehydratase by phenylalanine concentrations up to 200 mm in certain variants (Nelms et al. 1992). These variants were incorporated into an E. coli K12 strain to construct a pathway producing S-mandelic acid via this modified l-phenylalanine pathway (Sun et al. 2011). In addition to directed evolution techniques, computational design strategies provide further possibilities for configuring novel allosteric modulators (for a review of this subject, see Lu et al. 2014).

Increased Substrate Specificity

Enzyme engineering can also play a key role in shaping enzyme specificity and, as a result, limiting erroneous and potentially deleterious side reactions and products. By using existing promiscuous enzyme activities as a starting point for directed evolution, the creation of new enzymatic functions, such as catalyzing reactions on nonnative substrates, has been shown (Broadwater et al. 2002). The knowledge of the promiscuous activities catalyzed by an enzyme not only provides a starting point for engineering novel functionalities, but it has shown to guide the engineering of native activities with increased specificity and higher activity (Yoshikuni et al. 2006). For example, γ-humulene synthase, a sesquiterpene synthase from Abies grandis (Steele et al. 1998; Little and Croteau 2002), produces 52 different sesquiterpenes from a sole substrate, farnesyl diphosphate, through a wide variety of cyclization mechanisms (Lesburg et al. 1997; Starks et al. 1997; Caruthers et al. 2000; Rynkiewicz et al. 2001). Yoshikuni et al. (2006) showed that site-directed mutagenesis of a set of previously identified plasticity residues shifted the relative selectivity of one product for another by 100- to 1000-fold. An additional example of how directed evolution improved enzyme specificity has been reported in xylose isomerase-based pathways in S. cerevisiae, which typically suffer from poor ethanol productivity and low xylose consumption rates. Improving the specific activity of a heterologous enzyme, Piromyces sp. xylose isomerase, via rounds of random mutagenesis and growth-based screening has led to a variant that showed a 77% increase in activity. When expressed in a minimally engineered yeast host, the strain improved its aerobic growth rate by 61-fold and ethanol and xylose consumption rates by nearly eightfold (Lee et al. 2012). Identifying potentially promiscuous enzyme activities is a major challenge and has been one of the main roles of certain computational pathway prediction algorithms, such as the Biochemical Network Integrated Computational Explorer (BNICE) framework (Hatzimanikatis et al. 2005). BNICE uses existing enzyme chemistry as a groundwork for novel enzyme mechanisms that can be fine-tuned and tailored via minimal enzyme reengineering. Several examples of in silico strategies for the reengineering of naturally occurring enzymes into novel biocatalysts are shown by the work of (1) Cho et al. (2010), who predicted novel enzyme activities on the basis of physicochemical properties of substrate/product pairs, (2) Brunk et al. (2012), who predicted novel enzyme activity within a biosynthetic pathway (Henry et al. 2010) on the basis of 3D protein structural characteristics and molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 4), and (3) Campodonico et al. (2014), who predicted enzyme similarity on the basis of enzyme commission classification. In certain cases, a comprehensive assessment was performed for 20 predicted heterologous pathways in E. coli (Campodonico et al. 2014).

ENGINEERING AT THE REACTOME LEVEL

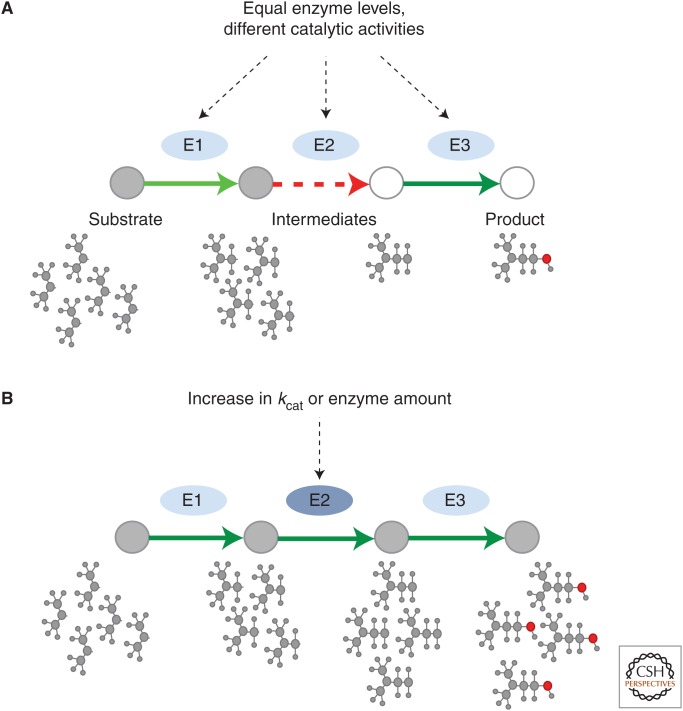

In the previous sections, we have shown the importance of engineering correctly folded and catalytically active pathway enzymes. Here, we address the significance of balanced metabolite fluxes. Achieving maximum protein abundance does not necessarily give rise to highest product titers (Jones et al. 2000). Simultaneously, an increase in Vmax (=kcat × [E]) of a heterologous enzyme can create a metabolic sink causing nutrient limitation and growth inhibition (Fig. 5). Excessive catalytic turnover can also lead to intermediate buildup causing feedback inhibition or even toxicity (Ajikumar et al. 2010). Therefore, it is important to balance protein synthesis and activity levels to engineer a pathway with stable steady-state behavior and minimal metabolic burden (Fig. 5). In this section, we review methods to assess the optimal design space of metabolic pathways. Studies are beginning to use multivariate statistical approaches to guide predictable forward engineering efforts. We will also present a putative workflow to guide the integration of a heterologous pathway within the host metabolic and regulatory network.

Figure 5.

Reactome-level optimization. (A) Nonoptimal metabolite flux limited by low turnover of one pathway enzyme. (B) Optimal flux through the pathway can be achieved by engineering the bottleneck enzyme leading to either higher enzyme levels or increased catalytic activity.

Balanced Pathway Fluxes

Unlike other areas of engineering, biological systems are extremely nonlinear, which makes predicting how pathway networks function in vivo a challenge. Often, engineered pathways have been optimized through sampling of large design spaces (Pfleger et al. 2006; Lütke-Eversloh and Stephanopoulos 2008; Du et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012a; Xu et al. 2013; Nowroozi et al. 2014). Such combinatorial approaches are specifically valuable for organisms with less-defined genetic and metabolic networks (Oliver et al. 2014). However, combinatorial libraries are limited by analytical capabilities and require high-throughput screens or selection assays. For a review on high-throughput library selection and screening strategies, the reader is referred to Dietrich et al. (2010).

The main difficulty remains in understanding how interactions among components of a biochemical network within an organism give rise to the function and behavior of the entire system. In lieu of probing large design spaces through traditional metabolite analysis, a few studies have used smaller data sets with multivariate statistical analysis to predict behavior. The resulting models can be used to forward-engineer required enzyme levels for optimal pathway flux. Lee et al. (2013), for example, created a regression model to analyze a subset of a combinatorial promoter library. To assess the capacity of the generated model, they chose to express the highly branched violacein pathway and trained the model on only a small fraction of the measured data (∼100 random clones, 3% of total library). The model was able to correctly predict production levels of the violacein congeners under different expression conditions with a correlation coefficient between 0.77 and 0.92, which was sufficient to guide further optimization efforts.

Alonso-Gutierrez et al. (2014) used principal component analysis of quantitative proteomics data (PCAP) to correlate product titers in E. coli. Gaining insight into optimal pathway stoichiometry of limonene biosynthesis, the investigators were able to further improve yields by ∼40%. Expression timing was also addressed in this study, and there is an indication that different induction times lead to largely varied production levels because of toxic intermediate accumulation. Altogether, this study revealed the delicate balance between enzyme levels that is required for optimal pathway performance. At the same time, the holistic approach of PCAP emphasized that multiple optima exist in the combinatorial expression space of a mevalonate-dependent pathway. These examples show pathway-centric approaches by correlating protein synthesis and product flux. Such statistical approaches can be further complemented with constraint-based flux balance analysis (FBA) to create an integrative approach, which also considers the host metabolism (Brunk et al. 2016).

FUTURE DIRECTIONS TOWARD INTEGRATED APPROACHES IN METABOLIC ENGINEERING

To tackle the existing challenges in metabolic engineering, strategies need to account for all aspects of product synthesis in which control can be exerted: the transcriptome, the translatome, the proteome, and the reactome (Fig. 1). First, engineering the transcriptome involves manipulation of mRNA stability and expression levels, which is commonly mastered through promoter and terminator strength engineering. Second, translatome engineering requires an understanding of the factors involved in translational efficiency and cotranslational processes such as folding and translocation. Third, the design of chemical transformations and protein engineering is controlled at the proteome level. And last, reactome manipulations allow us to address aspects of enzymes ratios and, therefore, metabolite flux (Fig. 1). Inaccuracies at any of these levels can prohibit successful implementation of an engineered pathway. Here, we emphasize the current potentials at the different control levels.

Translatome Manipulations Toward Reliable Enzyme Expression

Despite having made great strides in metabolic engineering and synthetic biology (i.e., orthogonal design, parts characterization), there remains a gap between designed and measured enzyme activity. For example, protein solubility and, therefore, activity is currently optimized through a rather random approach (Batard et al. 2000; Burgess-Brown et al. 2008; Cheong et al. 2015). General optimization strategies for heterologous enzyme synthesis that do not suffer losses of catalytic activity are currently lacking. To narrow this gap between design and biology, a deeper characterization of the factors involved in gene expression is desired (Latif et al. 2014). Currently, computational models only exist for the analysis and prediction of translation initiation rates (for a review on this topic, see Reeve et al. 2014). Beyond controlling translational efficiency, there is a prevailing need to establish design guidelines for robust and specific codon optimization approaches. For this goal, emerging methods to experimentally assess ribosomal speed for different hosts have the potential to provide a reliable foundation for computational codon optimization strategies (Ingolia et al. 2009; Chevance et al. 2014; Hockenberry et al. 2014; Latif et al. 2014).

Protein-Level Manipulations Toward Efficient Enzyme Catalysis

Rational design will not move beyond its current limitations until our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of enzyme catalysis has improved. A great deal of advancement has been made in understanding structure–function–activity relationships in enzyme chemistry (Thornton et al. 2000). This is, in part, a result of the ever-increasing number of high-resolution structures available through X-ray crystallography (Berman et al. 2003) as well as the insights on detailed enzyme catalytic mechanisms from numerous theoretical-based studies (Colombo et al. 2002; Brunk and Rothlisberger 2015). Understanding protein promiscuity and its great potential for the design of novel catalysts has been the subject of many recent reviews (Nobeli et al. 2009; Humble and Berglund 2011). Synergistic efforts to couple computational enzyme design and metabolic pathway engineering with directed evolution brings promise of reengineering biosynthetic pathways and, in particular, in secondary metabolism, which offers a wider range of metabolic and biosynthetic routes, an increased scope of substrates and products, and has been shown to be less shaped by natural selection pressures than that of primary metabolism (Bar-Even and Tawfik 2013).

Reactome Manipulations Toward Optimal Production Fluxes

Typically, designing a new technical system requires starting from scratch and testing various potential prototypes, usually by means of trial and error. Thus, designing a procedure of interpretation or translation from biology to technology is a necessary goal to overcome the engineering bottlenecks. Although databases, such as KEGG (Kanehisa 2002) and BRENDA (Schomburg et al. 2004; Chang et al. 2009), provide information mainly focused on primary pathways in metabolism, categorization of novel biosynthetic pathways, the enzymes involved in biosynthesis, and the small molecules tailored to desired tasks will also be needed. Computational tools that can have access to resources such as these will undoubtedly have the potential to predict pathways, identify variations in enzymes, and model these changes in genome-scale metabolic networks of candidate host systems. Being able to model, understand, and predict complex metabolic networks has been made possible by recent developments of genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), which have been reconstructed for >60 organisms (Reed and Palsson 2003; Monk et al. 2013; Bordbar et al. 2014). These reconstructions are converted into constraint-based models (Becker et al. 2007), allowing useful calculations like FBA (Orth et al. 2010) to be performed. Methods such as these are complementary and amenable to pathway design and offer great promise for advancing the field of synthetic pathway engineering and the design of microbial biofactories (Monk et al. 2014; Brunk et al. 2016).

CONCLUSIONS

Recent developments in the field of metabolic engineering bring promise to the design of biosynthetic pathways, in which entire metabolic pathways can be (re)designed and expressed in host organisms. We attempt to give the reader a comprehensive view on the aspects pertinent to successful pathway engineering. Additionally, we emphasize that there remains a gap between optimization efforts at the molecular level and those at the systems level. One important consideration is to address the different complications or bottlenecks that may occur on vastly different chemical and biological scales. Feasibility of engineered components can be assessed using molecular-scale analyses, which typically evaluate feasibility in terms of the ability of enzymes to catalyze a desired transformation on a substrate, and systems-level analyses, which generally assess feasibility on the basis of changes in the range of intracellular metabolites and enzyme concentrations (e.g., proteome allocations, pathway ratios). At the same time, these remaining challenges reveal many opportunities to fill knowledge gaps and develop more sophisticated design tools in metabolic engineering. First, we emphasize that computational predictions of pathway performance will only be as accurate as our models that heavily rely on existing omics data sets. Within the context of the design–build–test–learn cycle, we are successfully designing and building production strains; however, there is a delay in the learning process because “testing” is highly limited by the capabilities of existing high-throughput analytical methods. Additional omics data sets of rationally engineered microbes are required to build accurate prediction models and to facilitate the de novo design of constructs. Second, there remains a need to create an open access knowledge database to organize and analyze large data sets. And last, “learning” is informed by our basic understanding of cellular processes. Yet, there remain multiple control levels that are not well understood on a cellular scale such as allosteric regulation exerted through interaction between proteins and metabolites. Posttranslational regulation is an additional control layer that has recently attracted much attention because of novel methods assessing posttranslational modifications on an organism scale. Future milestones in “test and learn” will transform the field of metabolic engineering from a semirational to a fully rational forward engineering discipline.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. Daniel Liu, Dr. Sarah Richardson, Dr. Nathan Hillson, and Dr. Christopher Petzold for valuable comments and discussion on this review. The authors also thank Prof. Vassily Hatzimankatis and Prof. Ursula Rothlisberger for the many useful discussions on computational design strategies over the years. This work is funded by the Department of Energy Joint BioEnergy Institute (jbei.org) supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, through contract DE-AC02-05CH11231 between Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the U.S. Department of Energy and by the Synthetic Biology Engineering Research Center (SynBERC) through National Science Foundation Grant NSF EEC 0540879. The authors acknowledge support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant p2elp2_148961 to E.B.).

Footnotes

Editors: Daniel G. Gibson, Clyde A. Hutchison III, Hamilton O. Smith, and J. Craig Venter

Additional Perspectives on Synthetic Biology available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Agashe D, Martinez-Gomez NC, Drummond DA, Marx CJ. 2013. Good codons, bad transcript: Large reductions in gene expression and fitness arising from synonymous mutations in a key enzyme. Mol Biol Evol 30: 549–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajikumar PK, Xiao WH, Tyo KEJ, Wang Y, Simeon F, Leonard E, Mucha O, Phon TH, Pfeifer B, et al. 2010. Isoprenoid pathway optimization for taxol precursor overproduction in Escherichia coli. Science 330: 70–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Gutierrez J, Kim E-M, Batth TS, Cho N, Hu Q, Chan LJG, Petzold CJ, Hillson NJ, Adams PD, Keasling JD, et al. 2014. Principal component analysis of proteomics (PCAP) as a tool to direct metabolic engineering. Metabol Eng 28C: 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold FH. 1998. Design by directed evolution. Acc Chem Res 31: 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Even A, Tawfik DS. 2013. Engineering specialized metabolic pathways—Is there a room for enzyme improvements? Curr Opin Biotechnol 24: 310–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batard Y, Hehn A, Nedelkina S, Schalk M, Pallett K, Schaller H, Werck-Reichhart D. 2000. Increasing expression of P450 and P450-reductase proteins from monocots in heterologous systems. Arch Biochem Biophys 379: 161–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker SA, Feist AM, Mo ML, Hannum G, Palsson BO, Herrgard MJ. 2007. Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: The COBRA toolbox. Nat Protoc 2: 727–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman H, Henrick K, Nakamura H. 2003. Announcing the worldwide protein data bank. Nat Struct Biol 10: 980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazeck J, Garg R, Reed B, Alper HS. 2012. Controlling promoter strength and regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using synthetic hybrid promoters. Biotechnol Bioeng 109: 2884–2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolon DN, Voigt CA, Mayo SL. 2002. De novo design of biocatalysts. Curr Opin Chem Biol 6: 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordbar A, Monk JM, King ZA, Palsson BO. 2014. Constraint-based models predict metabolic and associated cellular functions. Nat Rev Genet 15: 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornscheuer UT, Pohl M. 2001. Improved biocatalysts by directed evolution and rational protein design. Curr Opin Chem Biol 5: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann-Chen S, Flock T, Cahn JKB, Snow CD, Brustad EM, McIntosh JA, Meinhold P, Zhang L, Arnold FH. 2013. General approach to reversing ketol-acid reductoisomerase cofactor dependence from NADPH to NADH. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 10946–10951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadwater JA, Whittle E, Shanklin J. 2002. Desaturation and hydroxylation. Residues 148 and 324 of Arabidopsis FAD2, in addition to substrate chain length, exert a major influence in partitioning of catalytic specificity. J Biol Chem 277: 15613–15620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk E, Rothlisberger U. 2015. Mixed quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical molecular dynamics simulations of biological systems in ground and electronically excited states. Chem Rev 115: 6217–6263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk E, Neri M, Tavernelli I, Hatzimanikatis V, Rothlisberger U. 2012. Integrating computational methods to retrofit enzymes to synthetic pathways. Biotechnol Bioeng 109: 572–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk E, George KW, Alonso-Gutierrez J, Thompson M, Baidoo E, Wang G, Petzold CJ, McCloskey D, Monk J, Yang L, et al. 2016. Characterizing strain variation in engineered E. coli using a multi-omics-based workflow. Cell Syst 2: 335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brustad EM, Arnold FH. 2011. Optimizing non-natural protein function with directed evolution. Curr Opin Chem Biol 15: 201–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess-Brown NA, Sharma S, Sobott F, Loenarz C, Oppermann U, Gileadi O. 2008. Codon optimization can improve expression of human genes in Escherichia coli: A multi-gene study. Protein Expr Purif 59: 94–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campodonico MA, Andrews BA, Asenjo JA, Palsson BO, Feist AM. 2014. Generation of an atlas for commodity chemical production in Escherichia coli and a novel pathway prediction algorithm, GEM-Path. Metab Eng 25: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannarozzi G, Cannarrozzi G, Schraudolph NN, Faty M, von Rohr P, Friberg MT, Roth AC, Gonnet P, Gonnet G, Barral Y. 2010. A role for codon order in translation dynamics. Cell 141: 355–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruthers JM, Kang I, Rynkiewicz MJ, Cane DE, Christianson DW. 2000. Crystal structure determination of aristolochene synthase from the blue cheese mold, penicillium roqueforti. J Biol Chem 275: 25533–25539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A, Scheer M, Grote A, Schomburg I, Schomburg D. 2009. BRENDA, AMENDA and FRENDA the enzyme information system: New content and tools in 2009. Nucleic Acids Res 37: D588–D592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong DE, Ko KC, Han Y, Jeon HG, Sung BH, Kim GJ, Choi JH, Song JJ. 2015. Enhancing functional expression of heterologous proteins through random substitution of genetic codes in the 5′ coding region. Biotechnol Bioeng 112: 822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevance FF, Le Guyon S, Hughes KT. 2014. The effects of codon context on in vivo translation speed. PLoS Genet 10: e1004392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho A, Yun H, Park JH, Lee SY, Park S. 2010. Prediction of novel synthetic pathways for the production of desired chemicals. BMC Syst Biol 4: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciryam P, Morimoto RI, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, O'Brien EP. 2013. In vivo translation rates can substantially delay the cotranslational folding of the Escherichia coli cytosolic proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E132–E140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb RE, Sun N, Zhao H. 2013. Directed evolution as a powerful synthetic biology tool. Methods 60: 81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo MC, Guidoni L, Laio A. 2002. Hybrid QM/MM Car–Parrinello simulations of catalytic and enzymatic reactions. CHIMIA Int J Chem 56: 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Currin A, Swainston N, Day PJ, Kell DB. 2015. Synthetic biology for the directed evolution of protein biocatalysts: Navigating sequence space intelligently. Chem Soc Rev 44: 1172–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damborsky J, Brezovsky J. 2014. Computational tools for designing and engineering enzymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol 19: 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JH, Rubin AJ, Sauer RT. 2011. Design, construction and characterization of a set of insulated bacterial promoters. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 1131–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng MD, Severson DK, Grund AD, Wassink SL, Burlingame RP, Berry A, Running JA, Kunesh CA, Song L, Jerrell TA, et al. 2005. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for industrial production of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine. Metab Eng 7: 201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich JA, McKee AE, Keasling JD. 2010. High-throughput metabolic engineering: Advances in small-molecule screening and selection. Annu Rev Biochem 79: 563–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG. 1996. Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J Mol Biol 260: 649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Yuan Y, Si T, Lian J, Zhao H. 2012. Customized optimization of metabolic pathways by combinatorial transcriptional engineering. Nucleic Acids Res 40: e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueber JE, Wu GC, Malmirchegini GR, Moon TS, Petzold CJ, Ullal AV, Prather KLJ, Keasling JD. 2009. Synthetic protein scaffolds provide modular control over metabolic flux. Nat Biotechnol 27: 753–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvir S, Velten L, Sharon E, Zeevi D, Carey LB, Weinberger A, Segal E. 2013. Deciphering the rules by which 5′-UTR sequences affect protein expression in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: E2792–E2801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluman N, Navon S, Bibi E, Pilpel Y. 2014. mRNA-programmed translation pauses in the targeting of E. coli membrane proteins. eLife 10.7554/eLife.03440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good MC, Zalatan JG, Lim WA. 2011. Scaffold proteins: Hubs for controlling the flow of cellular information. Science 332: 680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman DB, Church GM, Kosuri S. 2013. Causes and effects of N-terminal codon bias in bacterial genes. Science 342: 475–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould N, Hendy O, Papamichail D. 2014. Computational tools and algorithms for designing customized synthetic genes. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C, Govindarajan S, Minshull J. 2004. Codon bias and heterologous protein expression. Trends Biotechnol 22: 346–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzimanikatis V, Li C, Ionita JA, Henry CS, Jankowski MD, Broadbelt LJ. 2005. Exploring the diversity of complex metabolic networks. Bioinformatics 21: 1603–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry CS, Broadbelt LJ, Hatzimanikatis V. 2010. Discovery and analysis of novel metabolic pathways for the biosynthesis of industrial chemicals: 3-Hydroxypropanoate. Biotechnol Bioeng 106: 462–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilvert D. 2013. Design of protein catalysts. Annu Rev Biochem 82: 447–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenberry AJ, Sirer MI, Nunes Amaral LA, Jewett MC. 2014. Quantifying position-dependent codon usage bias. Mol Biol Evol 31: 1880–1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humble MS, Berglund P. 2011. Biocatalytic promiscuity. Eur J Organic Chem 2011: 3391–3401. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt RC, Simhadri VL, Iandoli M, Sauna ZE, Kimchi-Sarfaty C. 2014. Exposing synonymous mutations. Trends Genet 30: 308–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemura T. 1985. Codon usage and tRNA content in unicellular and multicellular organisms. Mol Biol Evol 2: 13–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illanes A, Cauerhff A, Wilson L, Castro GR. 2012. Recent trends in biocatalysis engineering. Biores Technol 115: 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JRS, Weissman JS. 2009. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science 324: 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MA, Sternes PR, Mudge SR, Graham MW, Birch RG. 2014. Design rules for efficient transgene expression in plants. Plant Biotechnol J 12: 925–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakočiūnas T, Bonde I, Herrgård M, Harrison SJ, Kristensen M, Pedersen LE, Jensen MK, Keasling JD. 2015. Multiplex metabolic pathway engineering using CRISPR/Cas9 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng 28: 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayapal KP, Philp RJ, Kok YJ, Yap MGS, Sherman DH, Griffin TJ, Hu WS. 2008. Uncovering genes with divergent mRNA-protein dynamics in Streptomyces coelicolor. PLoS ONE 3: e2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, Doyle L, Röthlisberger D, Zanghellini A, Gallaher JL, Betker JL, Tanaka F, Barbas CF III, et al. 2008. De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes. Science 319: 1387–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes TW, Zhao H. 2006. Directed evolution of enzymes and biosynthetic pathways. Curr Opin Microbiol 9: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Kim SW, Keasling JD. 2000. Low-copy plasmids can perform as well as or better than high-copy plasmids for metabolic engineering of bacteria. Metab Eng 2: 328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanaya S, Yamada Y, Kudo Y, Ikemura T. 1999. Studies of codon usage and tRNA genes of 18 unicellular organisms and quantification of Bacillus subtilis tRNAs: Gene expression level and species-specific diversity of codon usage based on multivariate analysis. Gene 238: 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M. 2002. The KEGG database. Novartis Found Symp 247: 91–101; discussion 101–103, 119–128, 244–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J, DeGrado WF. 2004. De novo design of catalytic proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 11566–11570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keasling JD. 2010. Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science 330: 1355–1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Oh JM, Kim IW, Sauna ZE, Calcagno AM, Ambudkar SV, Gottesman MM. 2007. A “silent” polymorphism in the MDR1 gene changes substrate specificity. Science 315: 525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Marcuschamer D, Ajikumar PK, Stephanopoulos G. 2007. Engineering microbial cell factories for biosynthesis of isoprenoid molecules: Beyond lycopene. Trends Biotechnol 25: 417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosuri S, Goodman DB, Cambray G, Mutalik VK, Gao Y, Arkin AP, Endy D, Church GM. 2013. Composability of regulatory sequences controlling transcription and translation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 14024–14029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza A, Curran K, Rey L, Alper H. 2014. A condition-specific codon optimization approach for improved heterologous gene expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Syst Biol 8: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latif H, Szubin R, Tan J, Brunk E, Lechner A, Zengler K, Palsson BO. 2014. A streamlined ribosome profiling protocol for the characterization of microorganisms. Biotechniques 58: 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt JM, Alper HS. 2015. Advances and current limitations in transcript-level control of gene expression. Curr Opin Biotechnol 34: 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Kim HU, Park JH, Park JM, Kim TY. 2009. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms: General strategies and drug production. Drug Discov Today 14: 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Jellison T, Alper HS. 2012. Directed evolution of xylose isomerase for improved xylose catabolism and fermentation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol 78: 5708–5716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee ME, Aswani A, Han AS, Tomlin CJ, Dueber LE. 2013. Expression-level optimization of a multi-enzyme pathway in the absence of a high-throughput assay. Nucl Acids Res 41: 10668–10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennen RM, Pfleger BF. 2013. Microbial production of fatty acid-derived fuels and chemicals. Curr Opin Biotechnol 24: 1044–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesburg CA, Zhai G, Cane DE, Christianson DW. 1997. Crystal structure of pentalenene synthase: Mechanistic insights on terpenoid cyclization reactions in biology. Science 277: 1820–1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li GW. 2015. How do bacteria tune translation efficiency? Curr Opin Microbiol 24: 66–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin PP, Rabe KS, Takasumi JL, Kadisch M, Arnold FH, Liao JC. 2014. Isobutanol production at elevated temperatures in thermophilic Geobacillus thermoglucosidasius. Metab Eng 24: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lithwick G, Margalit H. 2003. Hierarchy of sequence-dependent features associated with prokaryotic translation. Genome Res 13: 2665–2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little DB, Croteau RB. 2002. Alteration of product formation by directed mutagenesis and truncation of the multiple-product sesquiterpene synthases δ-selinene synthase and γ-humulene synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys 402: 120–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Huang W, Zhang J. 2014. Recent computational advances in the identification of allosteric sites in proteins. Drug Discov Today 19: 1595–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütke-Eversloh T, Stephanopoulos G. 2008. Combinatorial pathway analysis for improved l-tyrosine production in Escherichia coli: Identification of enzymatic bottlenecks by systematic gene overexpression. Metab Eng 10: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma SM, Garcia DE, Redding-Johanson AM, Friedland GD, Chan R, Batth TS, Haliburton JR, Chivian D, Keasling JD, Petzold CH, et al. 2011. Optimization of a heterologous mevalonate pathway through the use of variant HMG-CoA reductases. Metab Eng 13: 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DJ, Kortemme T. 2009. Computer-aided design of functional protein interactions. Nat Chem Biol 5: 797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollwitz B, Brunk E, Schmitt S, Pojer F, Bannwarth M, Schiltz M, Rothlisberger U, Johnsson K. 2012. Directed evolution of the suicide protein O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase for increased reactivity results in an alkylated protein with exceptional stability. Biochemistry 51: 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk JM, Charusanti P, Aziz RL, Lerman JA, Premyodhin N, Orth JD, Feist AM, Palsson BO. 2013. Genome-scale metabolic reconstructions of multiple Escherichia coli strains highlight strain-specific adaptations to nutritional environments. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 20338–20343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk J, Nogales J, Palsson BO. 2014. Optimizing genome-scale network reconstructions. Nat Biotechnol 32: 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JC, Arnold FH. 1996. Directed evolution of a para-nitrobenzyl esterase for aqueous-organic solvents. Nat Biotechnol 14: 458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutalik VK, Guimaraes JC, Cambray G, Lam C, Christoffersen MJ, Mai QA, Tran AB, Paull M, Keasling JD, Arkin AP, et al. 2013. Precise and reliable gene expression via standard transcription and translation initiation elements. Nat Methods 10: 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelms J, Edwards RM, Warwick J, Fotheringham I. 1992. Novel mutations in the pheA gene of Escherichia coli K-12 which result in highly feedback inhibition-resistant variants of chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydratase. Appl Environ Microbiol 58: 2592–2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissley DA, O’Brien EP. 2014. Timing is everything: Unifying codon translation rates and nascent proteome behavior. J Am Chem Soc 136: 17892–17898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobeli I, Favia AD, Thornton JM. 2009. Protein promiscuity and its implications for biotechnology. Nat Biotechnol 27: 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowroozi FF, Baidoo EEK, Ermakov S, Redding-Johanson AM, Batth TS, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD. 2014. Metabolic pathway optimization using ribosome binding site variants and combinatorial gene assembly. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98: 1567–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver JWK, Machado IMP, Yoneda H, Atsumi S. 2014. Combinatorial optimization of cyanobacterial 2,3-butanediol production. Metab Eng 22: 76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth JD, Thiele I, Palsson BO. 2010. What is flux balance analysis? Nat Biotechnol 28: 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddon CJ, Westfall PJ, Pitera DJ, Benjamin K, Fisher K, McPhee D, Leavell MD, Tai A, Main A, Eng D, et al. 2013. High-level semi-synthetic production of the potent antimalarial artemisinin. Nature 496: 528–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne SH. 2015. The utility of protein and mRNA correlation. Trends Biochem Sci 40: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechmann S, Chartron JW, Frydman J. 2014. Local slowdown of translation by nonoptimal codons promotes nascent-chain recognition by SRP in vivo. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 1100–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleger BF, Pitera DJ, Smolke CD, Keasling JD. 2006. Combinatorial engineering of intergenic regions in operons tunes expression of multiple genes. Nat Biotechnol 24: 1027–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin JB, Kudla G. 2011. Synonymous but not the same: The causes and consequences of codon bias. Nat Rev Genet 12: 32–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelwijk FJ, Heyning PD, de Vos MGJ, Kiviet DJ, Tans SJ. 2011. Optimality and evolution of transcriptionally regulated gene expression. BMC Syst Biol 5: 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JL, Palsson BO. 2003. Thirteen years of building constraint-based in silico models of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 185: 2692–2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve B, Hargest T, Gilbert C, Ellis T. 2014. Predicting translation initiation rates for designing synthetic biology. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renata H, Wang ZJ, Arnold FH. 2015. Expanding the enzyme universe: Accessing non-natural reactions by mechanism-guided directed evolution. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 54: 3351–3367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röthlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, DeChancie J, Betker J, Gallaher JL, Althoff EA, Zanghellini A, Dym O, et al. 2008. Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature 453: 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rynkiewicz MJ, Cane DE, Christianson DW. 2001. Structure of trichodiene synthase from fusarium sporotrichioides provides mechanistic inferences on the terpene cyclization cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci 98: 13543–13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salis HM, Mirsky EA, Voigt CA. 2009. Automated design of synthetic ribosome binding sites to control protein expression. Nat Biotechnol 27: 946–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander IM, Chaney JL, Clark PL. 2014. Expanding Anfinsen’s principle: Contributions of synonymous codon selection to rational protein design. J Am Chem Soc 136: 858–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomburg I, Chang A, Ebeling C, Gremse M, Heldt C, Huhn G, Schomburg H. 2004. BRENDA, the enzyme database: Updates and major new developments. Nucleic Acids Res 32: D431–D433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP. 1997. Structural basis for cyclic terpene biosynthesis by tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase. Science 277: 1815–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CL, Crock J, Bohlmann J, Croteau R. 1998. Sesquiterpene synthases from Grand Fir (Abies grandis). Comparison of constitutive and wound-induced activities, and cDNA isolation, characterization, and bacterial expression of δ-selinene synthase and γ-humulene synthase. J Biol Chem 273: 2078–2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Ning Y, Liu L, Liu Y, Sun B, Jiang W, Yang C, Yang S. 2011. Metabolic engineering of the l-phenylalanine pathway in Escherichia coli for the production of S- or R-mandelic acid. Microb Cell Fact 10: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JM, Todd AE, Milburn D, Borkakoti N, Orengo CA. 2000. From structure to function: Approaches and limitations. Nat Struct Biol 7: 991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trudeau DL, Lee TM, Arnold FH. 2014. Engineered thermostable fungal cellulases exhibit efficient synergistic cellulose hydrolysis at elevated temperatures. Biotechnol Bioeng 111: 2390–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuller T, Carmi A, Vestsigian K, Navon S, Dorfan Y, Zaborske J, Pan T, Dahan O, Furman I, Pilpel Y. 2010. An evolutionarily conserved mechanism for controlling the efficiency of protein translation. Cell 141: 344–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma R, Schwaneberg U, Roccatano D. 2012. Computer-aided protein directed evolution: A review of web servers, databases and other computational tools for protein engineering. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2: e201209008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel C, Marcotte EM. 2012. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat Rev Genet 13: 227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Kim H, Cong L, Jeong J, Bang D, Church GM. 2012a. Genome-scale promoter engineering by coselection MAGE. Nat Methods 9: 591–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Si T, Zhao H. 2012b. Biocatalyst development by directed evolution. Biores Technol 115: 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Gu Q, Wang W, Wong L, Bower AGW, Collins CH, Koffas MAG. 2013. Modular optimization of multi-gene pathways for fatty acids production in E. coli. Nat Commun 4: 1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikuni Y, Ferrin TE, Keasling JD. 2006. Designed divergent evolution of enzyme function. Nature 440: 1078–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M, Guo J, Cha J, Chae M, Chen S, Barral JM, Sachs MS, Liu Y. 2013. Non-optimal codon usage affects expression, structure and function of clock protein FRQ. Nature 495: 111–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]