Abstract

A 52-year-old woman presented with recurrent, severe abdominal pain. Laboratory tests and imaging were insignificant, and treatment for functional dyspepsia was ineffective. The poorly localized, dull, and severe abdominal pain, associated with anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, was consistent with abdominal migraine. The symptoms were relieved by loxoprofen and lomerizine, which are used in the treatment of migraine. We herein report a case of abdominal migraine in a middle-aged woman. Abdominal migraine should be considered as a cause of abdominal pain as it might easily be relieved by appropriate treatment.

Keywords: abdominal migraine, abdominal pain, adult, unknown origin

Introduction

Abdominal pain is one of the most common complaints during outpatient examinations. In particular, due to recent developments in diagnostic imaging, imaging tests are frequently performed in patients with complaints of abdominal pain. Many cases in which abnormal findings are not observed are treated as cases of functional dyspepsia (FD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and other functional gastrointestinal disorders, or psychiatric disorders. We herein report a case of a middle-aged woman who was examined as an outpatient for complaints of repeated abdominal pain; she was diagnosed with abdominal migraine as a result of a detailed medical interview and showed a dramatic improvement of her symptoms after the administration of medications. Although there are very few reports on abdominal migraine occurring in adults, it is possible that many individuals remain undiagnosed. Thus, we present this report because we believe that our experience of and findings on this condition are significant.

Case Report

A 52-year-old woman presented at our outpatient department with complaints of abdominal pain that persisted for approximately half a day. Three months prior to presentation, she visited our hospital's emergency department for a fever, diarrhea, and vomiting. At the time, she was diagnosed with infectious enteritis. Symptomatic treatment led to recovery in approximately 3 days. Three weeks prior to presentation, she had experienced abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and vomiting that lasted for approximately half a day, but she had spontaneous remission. However, one week prior to presentation, she had experienced the same symptoms again and was seen by a local physician 5 days prior to presenting at our hospital. She was diagnosed with enteritis and prescribed medications: a proton pump inhibitor (lansoprazole), an intestinal regulator (bifidobacteria probiotic), and Chinese herbal medicine (daikenchuto), but she subsequently experienced repeated abdominal pain that lasted for approximately half a day and was thus examined at our department. The pain was located in the central portion of the trunk from the epigastric fossa to the lower abdomen, with no bias toward either the right or left side. The physical range of the pain was slightly indistinct. The pain was dull, and the most frequently experienced concomitant symptoms were poor appetite, nausea, and vomiting. The pain was not associated with prodromal symptoms, scintillating scotoma, or sensitivity to light or sound, and the patient did not experience constipation, diarrhea, or weight loss. The pain was continuous and although it was severe enough to prevent her from performing housework, the symptoms disappeared during intervals of no pain. She had a history of migraine since 30 years of age and had undergone an ectopic pregnancy (surgery) at 32 years of age. Her family medical history indicated that both her mother and younger brother had migraines. She experienced menopause at 46 years of age and had no history of alcoholic beverage consumption or smoking.

The physical findings were as follows: temperature, 36.6℃; blood pressure, 122/73 mmHg; heart rate, 74/min; and respiratory rate, 18/min. Her abdomen was flat and pliable, and although she reported pressure pain in the area extending from the epigastric fossa to the lower abdomen, there was neither rebound tenderness nor muscular defense.

Blood tests showed slightly elevated amylase levels, but no other abnormalities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Blood Test.

| Peripheral Blood | Blood CHemistry | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 4,500 /µL | TP | 7.4 mg/dL | CPK | 69 mg/dL |

| Neu | 53 % | Alb | 4.5 mg/dL | BUN | 15.1 mg/dL |

| Eos | 1 % | AST | 20 U/L | Cr | 0.6 mg/dL |

| Lym | 41 % | ALT | 12 U/L | Na | 140 mEq/L |

| Mon | 4 % | LDH | 187 U/L | K | 4.0 mEq/L |

| RBC | 442×104 /µL | ALP | 198 U/L | Cl | 103 mEq/L |

| Hb | 14.2 g/dL | T-Bil | 1.2 mg/dL | Ca | 10.2 mg/dL |

| Ht | 42.3 % | AMY | 157 U/L | CRP | 0.02 mg/dL |

| Plt | 15.7×104 /µL | Lipase | 35.7 U/L | ||

| FBS | 107 mg/dL | ||||

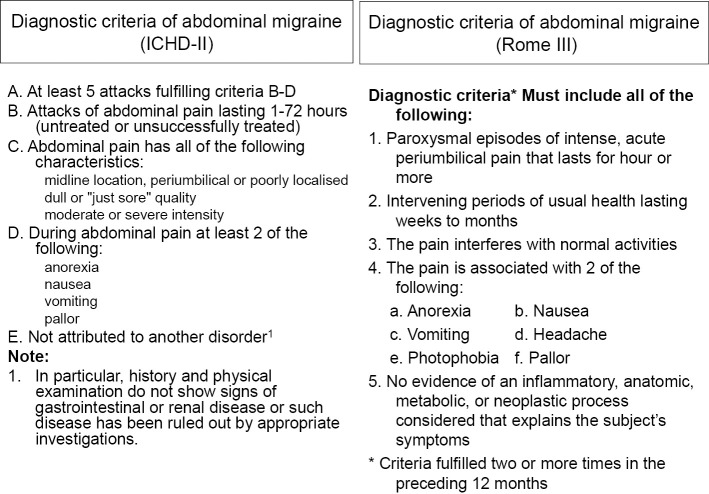

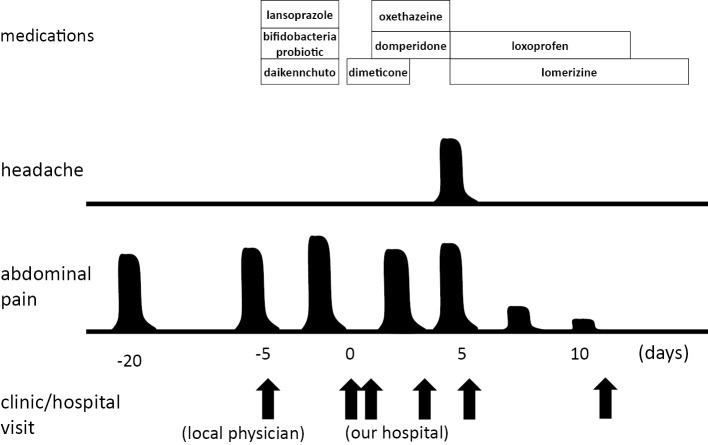

Although several imaging modalities were performed (abdominal ultrasound, abdominal contrast-enhanced CT, and upper and lower endoscopy), none showed abdominal findings that indicated any of the above disorders (all imaging tests, except for lower endoscopy, were performed while the patient was experiencing pain). Serological testing for immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies of H. pylori was negative. We suspected a functional disorder such as FD, and administered pharmaceuticals; a stomachic (oxethazaine), an intestinal regulator (dimeticone), and an antiemetic (domperidone). However, because there was no improvement in her symptoms and the pain recurred several times, the patient was examined three times as an outpatient during the week following her initial examination. During the third examination, she complained of a unilateral, throbbing headache in addition to her abdominal symptoms. Her medical history suggested that the cause of the headache to be a migraine; however, on reviewing her abdominal pain history, we discovered that it was marked by paroxysmal onset and went into spontaneous remission after approximately 12 hours of continuous pain. Both the location of the abdominal pain and the concomitant symptoms met the diagnostic standards for the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd Edition (ICHD-II) (1) and the Rome III criteria (2) for abdominal migraine (Fig. 1). After administering calcium blockers (lomerizine, 10 mg/day, as prophylactic treatment) and analgesics (loxoprofen as needed, 60 mg per use) for a few days, the abdominal pain disappeared along with the headache symptoms. Loxoprofen was tapered over the course of 2 weeks and she eventually used lomerizine alone (Fig. 2). The symptoms initially appeared to recur when lomerizine was stopped, but after 6 months of continuous lomerizine therapy, her abdominal pain completely disappeared and lomerizine was therefore stopped. Although she still experiences some occasional migraine headaches, they are being well controlled by occasional loxoprofen use, and there have been no episodes of abdominal pain.

Figure 1.

Diagnostic criteria for abdominal migraine.

Figure 2.

Clinical course.

Discussion

Abdominal migraine falls under the subcategory of childhood periodic syndromes in the ICHD-II (1) and is classified as a childhood functional gastrointestinal disorder in the Rome III critera (2). Both of these have established diagnostic criteria for the disorder. Both consider abdominal migraine to be a childhood disorder with the average age of onset at 8 years and a relatively high prevalence rate between 1% and 4% of children (3). It has a relatively good prognosis because most patients with childhood onset of abdominal migraine go into spontaneous remission by the time they reach adulthood. However, although abdominal pain goes into remission, it shifts to a conventional migraine headache in many cases. Dignan et al. observed patients with abdominal migraine for 10 years and reported that it shifted to migraine headache in 70% of them (4). Although this disease is referred to as “abdominal migraine,” the headache is absent or mild in most cases (5). It is considered to be a migraine-related disorder for the following reasons: 1) a notable family history of migraine, 2) in many cases, the disorder shifts to migraine headache after reaching adulthood, 3) predominance in women, 4) a relatively clearly-defined beginning and end of symptoms, and 5) in many cases, migraine medication is effective. Abdominal pain occurs in a poorly localized central abdominal area (6) and is often accompanied by concomitant symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, which are observed in cases of conventional migraine headaches. However, it is rarely associated with prodromal symptoms, scintillating scotoma, or sensitivity to light or sound.

In the present case, the pain experienced by this patient met the diagnostic criteria for abdominal migraine listed in both the ICHD-II and the Rome III criteria. However, a careful workup through the differential diagnosis was required because the duration of the interval between attacks was atypical, there have been few reports on this disorder occurring in adults (7-13), and it is a functional disorder.

Many patients who complain of epigastric symptoms during outpatient exams and who cannot be diagnosed by imaging tests are treated for FD. The present case was also treated for FD, but showed no signs of improvement. Using the Rome III criteria (14), except for the fact that the abdominal pain lasted for a short time, the patient's symptoms were consistent with epigastric pain syndrome (EPS). However, we believe that a diagnosis of abdominal migraine was accurate because 1) the abdominal pain was intense enough to significantly hinder the patient's daily living activities, 2) the appearance and disappearance of symptoms was clearly delineated, and 3) proton pump inhibitors were completely ineffective, whereas migraine medication was effective. In addition, postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) was ruled out because there was little relationship between food and the patient's symptoms. By using the Rome III criteria, many patients who complain of abdominal pain are ultimately diagnosed with FD, but some of these patients have refractory disorders, and they may be suffering from abdominal migraine. IBS was also ruled out because it has little relationship to constipation and abdominal pain.

In addition to FD and IBS, some diseases cause epigastric pain and are difficult to diagnose using imaging tests. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is distinguished by the fact that it causes paroxysmal abdominal pain; however, in the present case, because there was no elevation in the eosinophil levels in the peripheral blood and random biopsies performed during upper and lower endoscopies did not indicate eosinophil infiltration, it did not satisfy the diagnostic criteria (15) for eosinophilic gastroenteritis and was thus ruled out. In addition, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was ruled out because there was no history of allergic disease and CT did not indicate ascites or thickening of the intestinal tract walls. Chronic pancreatitis was ruled out because the patient had no history of alcohol consumption, i.e., neither abdominal ultrasound nor CT indicated calcification of the pancreas, irregular margins, or pancreatic duct enlargement. Moreover, chronic pancreatitis rarely presents with a paroxysmal onset of symptoms. Because the serum amylase levels were slightly elevated but lipase levels were within normal range, we believed it was a case of nonspecific elevation. Psychiatric disorders that may be accompanied by abdominal pain include some pain-related disorders such as depression and somatoform disorder. Consultation of the diagnostic standards for these disorders (DSM-IV) (16) indicated that because the patient did not exhibit a depressed mood or a loss of interest or happiness, depression could be ruled out. Because psychological factors are not related to pain onset, nausea, or continuous symptoms, pain disorder was also ruled out.

As there is no evidence-based treatment for abdominal migraine, current treatments are based on experience and consist of medication therapy and the improvement of activities of daily living. Improving the activities of daily living consists of receiving adequate sleep and avoiding stress, maintaining an adequate hydration level, and avoiding foods that contain vasoactive amines (e.g., cheese and wine). Medication therapy includes ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and other analgesics, which can be highly effective if taken soon after the onset of pain. In addition, triptans (17) and ergotamines (18) have been reported to be effective, and Roberts et al. reported that the effectiveness of triptans can be used in the differential diagnosis of abdominal migraine (7). When accompanied by nausea and vomiting, antiemetics (8) are used. Prophylactics include beta-blockers (propranolol), antiallergic agents (cyproheptadine), and pizotifen, which have been used experimentally (6,19). Research has indicated that the antiepileptic drugs valproic acid (20) and topiramate are also effective. When a calcium blocker (lomerizine), the cost of which is covered by national health insurance in Japan, was administered to the present patient, the patient experienced a marked improvement in her symptoms. Thus, this drug can be expected to be used for the treatment of abdominal migraine. However, as none of these drugs are used for the treatment of other gastrointestinal disorders, to make an accurate diagnosis, we must keep abdominal migraine in mind and provide appropriate medications.

A MEDLINE search of previous reports on abdominal migraine over the last 10 years using the key words “abdominal migraine” and “adult” revealed seven reports (total of ten cases) on adults (7-13). A summary of the 11 cases of adult abdominal migraine (ten cases plus the present case) is shown in Table 2. Four cases were men and seven were women. Five cases were aged in their twenties, two cases were in their thirties, one case was in his forties, and three cases, including the present case, were in their fifties. Except for the present case, there was a period of 1-15 years between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis, and in five of the ten cases, the onset of abdominal pain occurred when the patient had not yet reached adulthood. Thus, six cases were adult-onset, including the present case. Although there are very few studies on adult-onset abdominal migraine, Long et al. reported that detailed interviews of 85 patients with abdominal pain (median age, 37.6 years; age range, 13 to 72 years) whose pain could not be attributed to functional disorders revealed that 19 had a disease history implicating abdominal migraine and six presented the classical symptoms of abdominal migraine (21). Lundberg et al. reported that 12% of patients with migraine headache experience repeated intermittent abdominal pain, whereas only 1% of patients with muscle contraction headache experience abdominal pain (22). One of the main reasons why there have been such few reports on adult-onset abdominal migraine is because the disease is not widely known, indicating that the number of reports on proactive suspicion of the disease may increase in the future. The present patient occasionally experienced headache in addition to abdominal pain, and five of the other ten cases also reported concomitant headache (Table 2). The reason why abdominal migraine in adults is rarely accompanied by headache remains to be elucidated, which will be addressed through the study of additional cases in the future. Because abdominal pain is severe in cases of abdominal migraine, concomitant headache may be masked. Thus, when we meet a possible case of abdominal migraine, a careful interview process is required to determine the presence of concomitant headache.

Table 2.

Case Reports of Abdominal Migraine in Adult.

| Reference number | Age Sex | Time from onset to diagnosis | personal history of migraine | Family history of migraine | Headache | Treatment (abortive) | Treatment (prophylaxis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 48 F | 2 years | Yes | Yes | Yes (partly) | rizatriptan | topiramate |

| 24 F | 5 years | None noted | None noted | No | topiramate | ||

| 8 | 30 F | 15 years | None noted | None noted | No | ketprofen metoclopramide | |

| 9 | 20 M | 10 years | No | Yes | Yes (partly) | eletriptan | Valproate |

| 10 | 32 F | 5-6 years | None noted | Yes | No | topiramate | |

| 11 | 23 F | 7 years | No | Yes | Yes | pizotifen | |

| 12 | 22 M | 4 years | No | Yes | No | sumatriptan | topiramate verapamil |

| 13 | 52 M | 3 years | Yes | None noted | None noted | eletriptan prochlorperazine | |

| 56 M | 16 months | Yes | None noted | Yes | propranolol venlafaxine nebivolol amitriptyline | ||

| 27 F | 3 years | No | Yes | Yes | eletriptan | topiramate | |

| This case | 52 F | 1 month | Yes | Yes | Yes (partly) | loxoprofen | lomerizine |

Moskowitz's trigeminovascular theory (23) is the strongest contender for an explanation of the onset mechanism underlying migraine headache. It proposes that pain transmission is activated via vasodilation of the carotid and cranial blood vessels due to the action of serotonin, and this then causes headache. Internal serotonin is present in the brain and blood platelets, however, because >90% of internal serotonin is present in the enterochromaffin cells and most serotonin receptors are also located in the enteric canal, it is thought that the pathological characteristics of abdominal migraine include the same abnormal serotonin dynamics as those observed in migraine headache (24). In addition, from an anatomic point of view, it is believed that both central nervous system disorders and peripheral neuropathy (hypersensitivity of visceral nerves) are involved (24).

The present case had a history of migraine headache and was known to have experienced the sporadic onset of headaches, which were treated with single doses of NSAIDs. In general, most abdominal migraine experienced by patients during childhood shifted to migraine headache after the patient reached adulthood (1), however, the present case presented a typical migraine headache that shifted to abdominal migraine during middle age. The present case had a history of infectious enteritis 3 months prior to the onset of abdominal migraine. Although the mechanism of adult-onset abdominal migraine remains unclear, it was possible that infectious enteritis accelerated the hypersensitivity of the visceral nerves in the enteric canal, and as a result, caused adult-onset abdominal migraine. We would like to conduct future epidemiological research to determine whether the present case followed an extremely rare course or there are possibly many adult patients with abdominal migraine who remain undiagnosed.

Because the onset of migraine headache is considered most common between 20 and 40 years of age, it is important to question middle-aged or older patients undergoing examination for idiopathic abdominal pain about their history of migraine headache. Furthermore, many patients do not consider it important to mention headaches during history-taking. If a physician asks open-ended questions about the patients' medical history, patients may not mention migraine headaches. Therefore, it is important to use close-ended questions such as “Have you ever been told that you have a migraine headache?” or “Are you prone to headaches?”

We herein reported our experience of a middle-aged woman with abdominal migraine. Although there are many reports on abdominal migraine in children, the possibility of this disease must also be considered in adults whose abdominal pain cannot be attributed to any other disease, especially when the patient has a history of migraine headache.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia 24 (1 Suppl): 1-160, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rasquin A, Di Lorenzo C, Forbes D, et al. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: child/adolescent. Gastroenterology 130: 1527-1537, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Worawattanakul M, Rhoads JM, Lichtman SN, Ulshen MH. Abdominal migraine: prophylactic treatment and follow-up. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 28: 37-40, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dignan F, Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. The prognosis of childhood abdominal migraine. Arch Dis Child 84: 415-418, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cuvellier JC, Lepine A. Childhood periodic syndromes. Pediatr Neurol 42: 1-11, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. George R, Ishaq AA, David NK. Abdominal migraine. Evidence for existence and treatment options. Pediatr Drugs 4: 1-8, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roberts JE, deShazo RD. Abdominal migraine, another cause of abdominal pain in adults. Am J Med 125: 1135-1139, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cervellin G, Lippi G. Abdominal migraine in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med 33: 864.e3-864.e5, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamed SA. A migraine variant with abdominal colic and Alice in Wonderland syndrome: a case report and review. BMC Neurol 10: 1-5, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Woodruff AE, Cieri NE, Abeles J, Seyse SJ. Abdominal migraine in adults: a review of pharmacotherapeutic options. Ann Pharmacother 47: e27, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. d'Onofrio F, Cologno D, Buzzi MG, et al. Adult migraine: a new syndrome or sporadic feature of migraine headache? A case report. Eur J Neurol 13: 85-88, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Newman LC, Newman EB. Rebound abdominal pain: noncephalic pain in abdominal migraine is exacerbated by medication overuse. Headache 48: 959-961, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Evans RW, Whyte C. Cyclic vomiting syndrome and abdominal migraine in adults and children. Headache 53: 984-993, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 130: 1466-1479, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Talley NJ, Shorter RG, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a clinicopathological study of patients with disease of the mucosa, muscle layer, and subserosal tissues. Gut 31: 54-58, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Psychiatric Association In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition (DSM-IV). 1994: . [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kakisaka Y, Wakusawa K, Haginoya K, et al. Efficacy of sumatriptan in two pediatric cases with abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders: does the mechanism overlap that of migraine? J Child Neurol 25: 234-237, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Raina M, Chelimsky G, Chelimsky T. Intravenous dihydroergotamine therapy for pediatric abdominal migraines. Clin Pediatr 52: 918-921, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Symon DN, Russell G. Double blind placebo controlled trial of pizotifen syrup in the treatment of abdominal migraine. Arch Dis Child 72: 48-50, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan V, Sahami AR, Peebles R, Shaw RJ. Abdominal migraine and treatment with intravenous valproic acid. Psychosomatics 47: 353-355, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Long DE, Jones SC, Boyd N, Rothwell J, Clayden AD, Axon AT. Abdominal migraine: a cause of abdominal pain in adults? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 210-213, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lundberg PO. Abdominal migraine-diagnosis and therapy. Headache 15: 122-125, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moskowitz MA, Macfarlane R. Neurovascular and molecular mechanisms in migraine headaches. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 5: 159-177, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kakisaka Y, Uematsu M, Wang ZI, Haginoya K. Abdominal migraine reviewed from both central and peripheral aspects. World J Exp Med 20: 75-77, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]