Abstract

Eosinophilic myocarditis may be accompanied by Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS). We report a case of CSS that was accompanied by myocardial changes in the early stage. A 71-year-old woman complained of mild chest pain at rest, but routine echocardiography did not reveal any endocardial abnormalities. Four months later, the patient was hospitalized due to congestive heart failure with neuropathy of both upper extremities. A diagnosis of eosinophilic myocarditis was made based on the patient's laboratory results and the presence of mural thrombus. This case illustrates that, although early eosinophilic myocarditis is an important differential diagnosis in patients with chest pain, it may be difficult to identify in without an apparent mural thrombus.

Keywords: Churg-Strauss syndrome, eosinophilic myocarditis

Case Report

A 71-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with mild chest pain at rest that had persisted for 1 week. She had a medical history of bronchial asthma, chronic sinusitis, and splenectomy due to Banti disease at 38 years of age. Her vital signs were stable and a physical examination revealed no abnormalities. A chest radiograph appeared normal (Fig. 1a). A 12-lead electrocardiogram showed non-specific changes, which suggested mild left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (Fig. 1b). Echocardiography showed the mild thickening of the LV wall and minimal pericardial effusion behind the LV posterior wall (Fig. 2). The patient's white blood cell count was within the normal range (7,700 /μL). At that time, differential leukocyte counts were not automatically reported. The patient's serum troponin I level was slightly elevated (4.04 ng/mL), but her creatine kinase level was within normal limits.

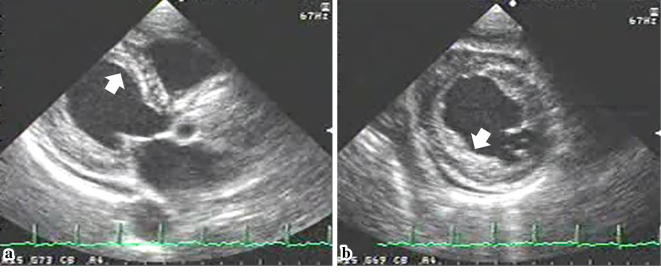

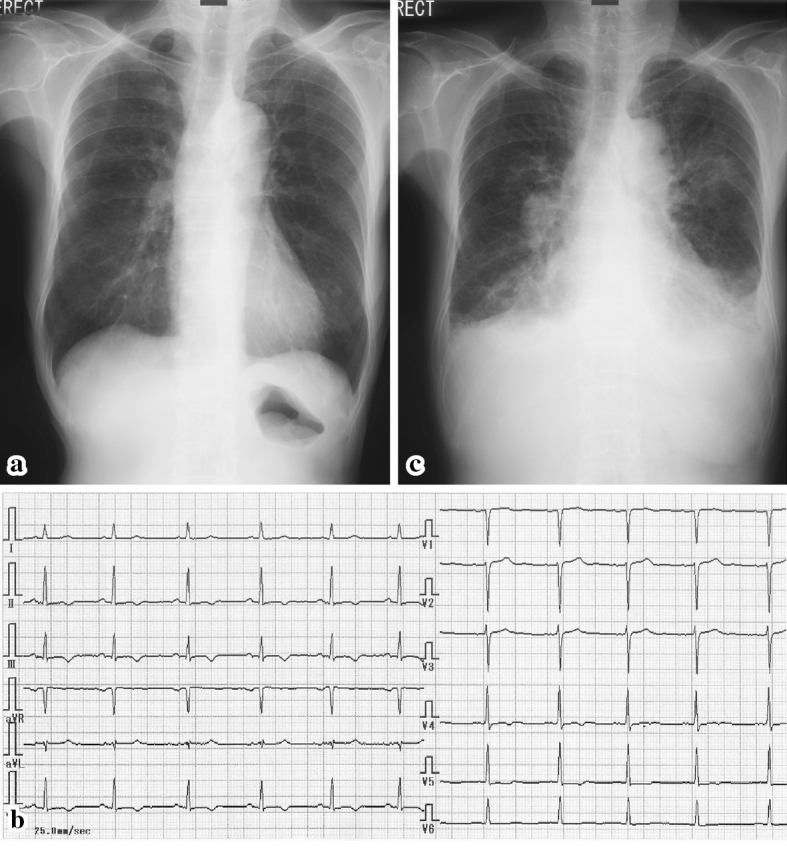

Figure 1.

Chest roentgenograms and electrocardiograms. A chest roentgenogram (a) from the first admission appeared normal, and an electrocardiogram (b) that was taken at the same time demonstrated nonspecific ST-T changes. However, the chest roentgenogram from the second admission (c) showed pleural effusion and infiltration, which was suggestive of eosinophilic pneumonia and heart failure. An electrocardiogram from the second admission showed almost no changes.

Figure 2.

Routine echocardiography from the patient’s first admission. Parasternal (a) and short-axis (b) views in the early stage of eosinophilic myocarditis show a superficial layer on the endocardium, suggesting a thrombus (arrow).

The normal appearance of the patient's coronary arteries on coronary angiography ruled out acute coronary syndrome. However, left ventriculography (LVG) showed the abnormal pooling of contrast medium within the myocardium (Fig. 3). Her chest pain spontaneously resolved, but careful outpatient observation was planned because a definitive diagnosis had not been made.

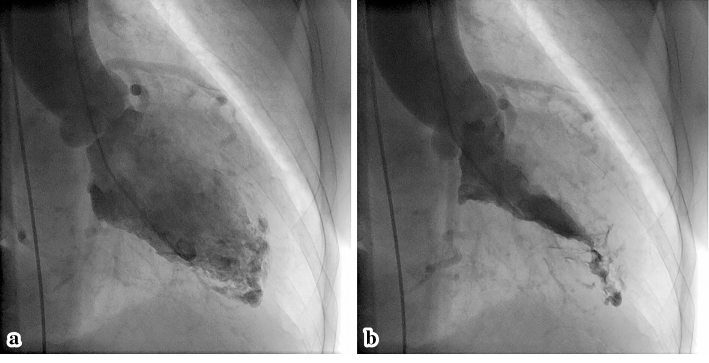

Figure 3.

Left ventriculography from the patient’s first admission. The diastolic (a) and systolic (b) phases show an abnormal pattern of contrast medium at the apex, with normal systolic function.

Four months later, she complained of progressive respiratory exhaustion. Her symptoms were suggestive of New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III heart failure. She also had fatigue, weight loss, and sensory neuropathy of the upper extremities. At this time, she was conscious and alert with a body temperature of 36.4℃, a heart rate of 90 beats/min, a blood pressure of 124/70 mmHg, a percutaneous oxygen saturation of 94% on room air, and coarse crackles in the bilateral lung fields. A chest radiograph revealed pulmonary congestion and infiltration (Fig. 1c). An electrocardiogram showed no dramatic changes. She was hospitalized again for a further work-up and treatment. A laboratory analysis showed marked eosinophilia: her white blood cell count was 10,700 /μL with 31% eosinophils (3,317 /μL). Her serum IgE level was elevated to 1,257 IU/mL. The patient was negative for anti-nuclear antibody, MPO-ANCA, and PR3-ANCA. Her brain natriuretic peptide was elevated to 1,164.6 pg/mL. A high plasma D-dimer level of 9.0 IU/L suggested the presence of a thrombus. Echocardiography showed a diffuse mural thrombus-like echo in the LV endocardium (Fig. 4a), although M-mode measurement demonstrated normal systolic function with an ejection fraction of 74%. Color Doppler echocardiography showed unusual blood flow from the endocardium and mural thrombus into the LV cavity during systole (Fig. 4b). Pulse Doppler echocardiography indicated diastolic dysfunction, pseudo-normal LV inflow pattern, a deceleration time of 131 ms, and an E/A ratio 1.83. We therefore thought that the patient's heart failure was caused by diastolic dysfunction and a decrease in stroke volume due to the thrombus that occupied the left ventricular cavity. Because of the patient's marked eosinophilia, bone marrow aspiration cytology was performed to exclude the possibility of lymphoproliferative abnormalities and genetic disorders. In accordance with the diagnostic criteria for allergic granulomatous angiitis proposed by the Research Committee of Intractable Vasculitis of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Japan (1998), the patient was diagnosed with Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) with an LV mural thrombus due to eosinophilic myocarditis. We also suspected that this was combined with eosinophilic pneumonia, because thoracentesis revealed an increase in eosinophils in the patient's pleural effusion.

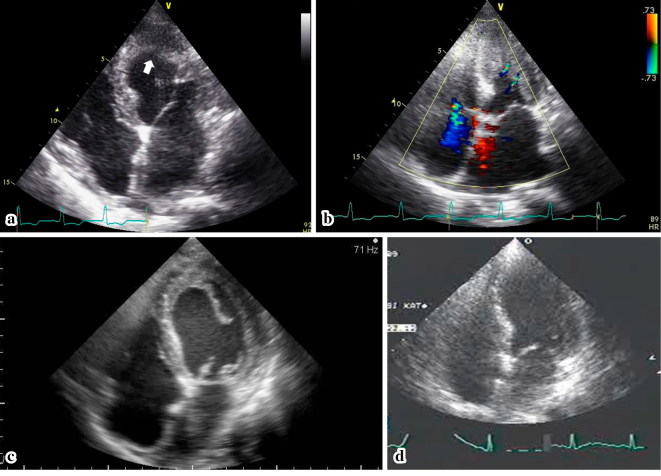

Figure 4.

Echocardiography at the time of the diagnosis of Churg-Strauss syndrome and after the initiation of treatment. The echocardiogram from the third day of the second admission (a) demonstrates a mural thrombus (white arrow) occupying the left ventricular cavity. Color Doppler echocardiography (b) shows two blood flows from the endocardium of the lateral wall. On the 20th day during steroid and anticoagulation therapy, the superficial layer of the thrombus was detached from the endocardium (c). On the 91st day, the thrombus had disappeared (d).

Treatment for heart failure was initiated with an intravenous infusion of carperitide 0.1γ for 6 days from the time admission. We also initiated steroid pulse therapy with prednisolone (PSL, 1,000 mg per day) for 3 days from the 6th day of hospitalization, followed by oral PSL (starting from 40 mg/day). Her eosinophilia disappeared soon after the start of PSL therapy; and her white blood cell count was 7,500 /μl with 0.1% of eosinophils (7.5 /μL) on the 12th day of hospitalization. The simultaneous administration of intravenous unfractionated heparin and oral warfarin was initiated. During anticoagulation therapy, echocardiography revealed that the mural thrombus was detached from the LV endocardium (Fig. 4c). At this time, the surgical resection of the thrombus was considered because of the high risk of thromboembolism. However, after a discussion between the patient, her family, and cardiac surgeons, she was treated conservatively. The volume of the thrombus eventually diminished without causing embolization. On the 40th day of hospitalization, she was discharged on oral PSL (25 mg/day). We performed echocardiography at our outpatient clinic on the 91st day and confirmed that the thrombus had disappeared (Fig. 4d). There were no after-effects on the patient's systolic function and the patient's diastolic function had recovered; the ejection fraction was 77%, the deceleration time was 210 ms, and the E/A ratio was 0.85. The dose of PSL was finally reduced to 7.5 mg, with the patient remaining in a stable condition.

Discussion

Eosinophilic myocarditis is considered to involve three steps of endocardial changes: necrotic, thrombotic, and fibrotic phases. The pathogenesis involves the infiltration of the endocardium and myocardium by cytotoxic eosinophils that are overproduced due to various causes, such as an allergic reaction due to CSS, as occurred in the present case. The eosinophilic granules cause tissue damage and inflammation of the endocardium, followed by formation of intramural thrombus. Eventually, the damaged myocardial tissues are replaced by fibrosis, which causes the diastolic and systolic dysfunction of the ventricle.

The early diagnosis of eosinophilic endocarditis is therefore crucial for preserving cardiac function, but requires careful echocardiographic examination for the following features of the disease: 1) diffuse thrombus deposits on the surface of the injured endocardium that may mimic myocardial thickening; 2) minimal thrombus growth on the LV apex; and 3) preserved systolic function in the presence of a mural thrombus. Because thrombus formation usually occurs at the most akinetic myocardium in cases of myocardial infarction and dilated cardiomyopathy, a mural thrombus on the normally functioning myocardium could be overlooked. In our patient, the subtle findings of LV thrombus formation were not identified on echocardiography during the patient's first hospitalization. On retrospective examination, however, a layer of mural thrombus could be distinguished (Fig. 1).

In the present case, the performance of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), in addition to echocardiography, might have led to an earlier diagnosis and treatment. MRI has now been demonstrated to clearly depict the cardiac involvement of eosinophilic myocarditis, including subendocardial inflammation and necrosis and endocardial thrombus formation in the early stages of the disease; in fact, it has become a standard examination for the early diagnosis of this disease (1-6). A previous study reported the characteristic features of mural thrombus formation on the endocardium, specifically multiple filling defects (with contrast medium) during LVG (5). However, LVG should not be performed if a thrombus is present in the LV. Endomyocardial biopsy is an important method for diagnosing eosinophilic myocarditis in patients who exhibit the eosinophilic infiltration of myocardial tissue. However, this invasive examination should not be performed unless other non-invasive tests are not sufficient to make a diagnosis. Unfortunately, we did not perform this examination at the first admission. Echocardiography and MRI are therefore important diagnostic modalities for patients with early eosinophilic myocarditis.

This case provided unique echocardiographic findings. The direction of the color flow from the endocardium to the LV cavity was considered to be a clue for the presence of endocardial thrombus formation. The image suggested that blood was squeezed through the gaps of the mural thrombi during the motion of the systolic wall (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, echocardiography during anticoagulation showed that the layer of thrombus on the endocardium was detached and present in the LV cavity (Fig. 4c). Based on these findings, we were convinced that both the apex and the mildly hypertrophic middle LV walls had mural thrombi on the surface. A previous report on a similar case of CSS with eosinophilic myocarditis showed that a thrombus in the LV apex caused the acute occlusion of the abdominal aorta (6). In the present case, although the LV wall motion was preserved and despite the risk of thromboembolism, the fragmented thrombus resolved with medical treatment without any consequences. We hope that these images and findings will be helpful for improving the early diagnosis and treatment of eosinophilic endocarditis in patients with CSS.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Pfell A, Brehm B, Lopatta E, et al. . Acute chest pain, heart failure, and eosinophilia in a woman without coronary disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 32: 1272-1274, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pitt M, Davies MK, Brady AJ. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: endomyocardial fibrosis. Heart 76: 377-378, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kleinfeldt T, Ince H, Nienaber CA. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: a rare case of Loeffler's endocarditis documented in cardiac MRI. Int J Cardiol 149: e30-e32, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Debl K, Djavidani B, Buchner S, et al. . Time course of eosinophilic myocarditis visualized by CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 10: 21, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pillar N, Halkin A, Aviram G. Hypereosinophilic syndrome with cardiac involvement: early diagnosis by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Can J Cardiol 28: 515.e11-515. e13, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Esposito A, De Cobelli F, Belloni E, et al. . Magnetic resonance imaging of a hypereosinophilic endocarditis with apical thrombotic obliteration in Churg-Strauss syndrome complicated with acute abdominal aortic embolic occlusion. Int J Cardiol 143: e48-e50, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]