Abstract

We herein report a novel mutation in a Japanese family with an X-linked Alport syndrome (AS) mutation in COL4A5. Patient 1 was a 2-year-old Japanese girl. She and her mother (patient 2) had a history of proteinuria and hematuria without renal dysfunction, deafness, or ocular abnormalities. Pathological findings were consistent with AS, and a genetic analysis revealed that both patients had a heterozygous mutation (c.2767G>C) in exon 32. In summary, the identification of mutations and characteristic pathological findings was useful in making a diagnosis of AS. For a close long-term follow-up, the early detection and treatment of women with X-linked AS are important.

Keywords: Alport syndrome, X-linked, COL4A5 mutation, woman

Introduction

Alport syndrome (AS) is a hereditary nephropathy characterized by a family history of hematuria, progressive renal failure, sensorineural hearing loss, and ocular abnormalities (1). Progression to renal failure is predictable in men, whereas the course of renal involvement is much more variable in women, remaining mild in the majority of patients. Approximately 80% of AS is inherited in an X-linked manner and is caused by mutations in the COL4A5 gene. Nearly all male patients will develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD), whereas heterozygous females exhibit a wide variability in disease severity (2,3). To date, more than 700 different COL4A5 mutations have been identified (4,5). We herein report a novel mutation in a Japanese family with an X-linked AS mutation in COL4A5.

Case Report

The patient (patient 1) was a 2-year-old Japanese girl who was the first child of healthy non-consanguineous parents. Her younger brother had no proteinuria or hematuria. Her maternal aunt had an episode of nephritis, and a renal biopsy was performed during childhood, but the findings were uncertain. At 14 months of age, patient 1 was referred to our hospital because of microscopic hematuria that had persisted from the neonatal period. She had no clinically detectable hearing loss or ocular abnormalities. A urine culture revealed no infection. At 15 months of age, enalapril malate was initiated for proteinuria, with a urinary protein/creatinine ratio (P/Cr) of 1.3-3.6 g/gCr. At 21 months of age, she was admitted to our hospital for a renal biopsy. On admission, a urinalysis showed 2+ proteinuria (P/Cr, 1.3 g/gCr) and 3+ hematuria, with the urine sediment containing >100 red cells per high-power field. Her blood urea nitrogen (BUN) level was 17.7 mg/dL, serum creatinine level was 0.22 mg/dL, serum total protein level was 5.9 g/dL, and albumin level was 3.7 g/dL. Serum C3 and C4 levels were 118.2 mg/dL and 24.8 mg/dL, respectively. Antinuclear antibodies were negative. Renal ultrasonography was unremarkable.

Her mother (patient 2) also had a history of proteinuria and hematuria without renal dysfunction, deafness, or ocular abnormalities. The pedigree of her family is shown in Fig. 1a. At 34 years of age, she was admitted to our hospital along with her daughter (patient 1) for a renal biopsy. A urinalysis showed 3+ proteinuria (P/Cr, 1.7 g/gCr) and 2+ hematuria, with the sediment containing 10-19 red cells per high-power field. Her BUN level was 20.0 mg/dL, serum creatinine level was 0.59 mg/dL, serum total protein level was 6.8 g/dL, and albumin level was 4.0 g/dL. Serum C3 and C4 levels were 134.4 mg/dL and 34.2 mg/dL, respectively. Antinuclear antibodies were negative. Renal ultrasonography showed a cystic lesion in the right kidney.

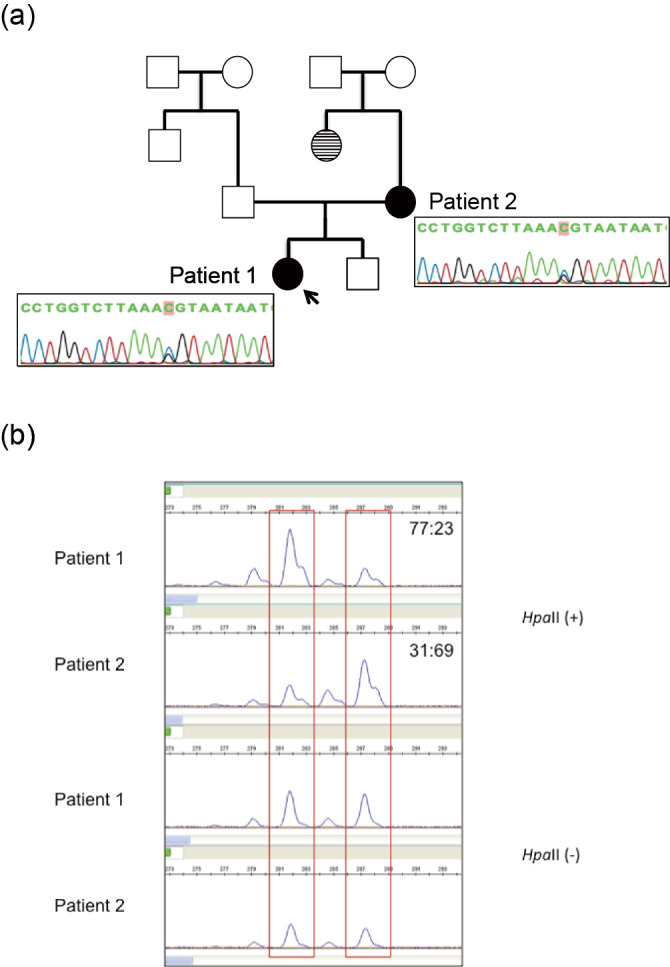

Figure 1.

(a) Pedigree and findings of COL4A5 mutation in two patients. The arrow indicates the proband. Unaffected individuals with kidney diseases are denoted by empty squares (men) and circles (women). Affected individuals with X-linked Alport syndrome are denoted by blackened circles (patients 1 and 2). Affected individuals with biopsy-unproven kidney disease are denoted by striped circles. Genetic analyses revealed that both patients had a heterozygous mutation (c. 2,767G>C) in exon 32. (b) X chromosome inactivation assays for our patients. In methylation-sensitive enzymes, a methylated allele is inactivated and cannot be digested by HpaII. Patient 1 and 2 both showed a random pattern with ratios of 77: 23 and 31: 69, respectively. It was impossible to distinguish whether the mutated allele was possessed by an activated or inactivated X chromosome because both had the same number of CAG repeats.

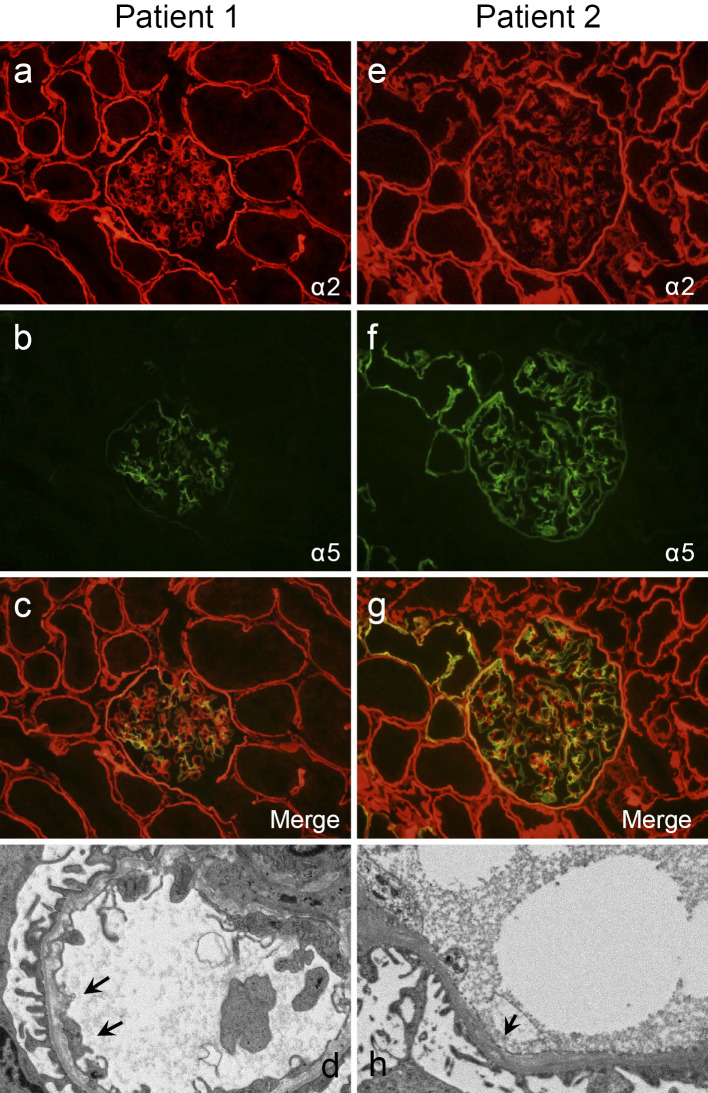

The renal biopsy findings of the two patients are shown in Fig. 2. In patient 1, 29 glomeruli were observed on light microscopy; the glomerulus, tubules, and interstitium showed no significant alterations. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining for alpha 5 chains of type IV collagen showed segmental and mosaic patterns in the glomerular basement membrane (GBM). Electron microscopy (EM) demonstrated diffusely thinned-out GBMs (139-143 nm) with focal lamellation and splitting. In patient 2, 40 glomeruli were observed on light microscopy, two of which were globally sclerotic. IF staining for alpha 5 chains of type IV collagen showed segmental and mosaic patterns in the GBM, Bowman's capsule, and distal tubular basement membrane (TBM). EM demonstrated diffusely thinned-out GBMs (149-166 nm) with dense granules and splitting. In both patients, the merged IF staining images for alpha 2 and 5 chains of type IV collagen clarified the findings of segmental and mosaic patterns in the GBM.

Figure 2.

Renal biopsy findings in X-linked Alport syndrome with a novel mutation. Patient 1 shows (a) a normal pattern of the alpha 2 chain of type IV collagen in the GBM and (b) segmental and mosaic patterns of the alpha 5 chain of type IV collagen in the GBM and the absence of staining in Bowman’s capsule and the TBM. (c) The merged findings of the alpha 2 and 5 chains of type IV collagen are shown. (d) Electron microscopy reveals a split lamina densa (arrows) and thin GBM. Patient 2 shows (e) a normal pattern of the alpha 2 chain of type IV collagen in the GBM and (f) a mosaic pattern of the alpha 5 chain of type IV collagen in the GBM and TBM. (g) The merged findings of the alpha 2 and 5 chains of type IV collagen are shown. (h) Electron microscopy reveals a split lamina densa (arrow). GBM: glomerular basement membrane, TBM: tubular basement membrane

A sequence analysis of COL4A5 in the index patient and her mother was performed. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kobe University School of Medicine, and written informed consent was obtained. Genomic DNA was isolated from each patient's peripheral blood leukocytes using the Quick Gene Mini 80 System (Kurabo Industries, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Mutational analyses of COL4A5 were performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and direct sequencing of genomic DNA of all exons and exon-intron boundaries. All 51 specific exons of COL4A5 were amplified by PCR. The PCR-amplified products were then purified and subjected to direct sequencing using a Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, USA) with an automatic DNA sequencer (ABI Prism 3130; Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The analysis revealed that both patients had a heterozygous mutation (c.2767G>C) in exon 32 (Fig. 1a). To investigate X chromosome inactivation, the human androgen receptor (HUMARA) assay was performed in both patients. Genomic DNA was digested by a methylation-sensitive enzyme, HpaII, at 37°C for 18 hours followed by PCR using DNA with HUMARA primers, as described previously (6). A DNA fragment analysis was performed on a 310 Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Fragment data analyses were performed using the Gene Mapper Software program (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The HUMARA assay for patients 1 and 2 revealed that the X chromosome inactivation pattern was 77:23 and 31:69, respectively (Fig. 1b).

Discussion

The index case was a 2-year-old girl with X-linked AS who had inherited a COL4A5 novel mutation (c.2767G>C) in exon 32 from her mother. Both patients had histories of hematuria and proteinuria without sensorineural hearing loss or ocular abnormalities. Renal biopsy findings indicated hereditary glomerulonephritis, and genetic analyses were useful in making a final diagnosis.

More than 700 disease-causing mutations have already been reported in COL4A5 (2,5). In men with X-linked AS, clinical features can be predicted from the location of COL4A5 mutations (3). Hematuria was noted earlier in patient 1. Pathologically, patient 1 had less signals in Bowman's capsule and the TBM compared with patient 2. These findings imply that patient 1 had more severe disease than patient 2. It reported that the genotype-phenotype correlations are not observed in women, even among family members (2,7). Although heterozygous female patients with X-linked AS have a normal COL4A5 allele, differences in X chromosome inactivation may influence the disease severity (2,8). However, the HUMARA assay in our cases did not confirm non-random X chromosome inactivation, so-called skewed X, since it is usually considered that the non-random inactivation pattern is >80:20 or <20:80 (9). Guo et al. reported that 90% of X chromosomes with a normal COL4A5 allele were inactivated in the kidney of a woman with a severe AS phenotype (10). The different patterns of X chromosome inactivation in the GBM may cause the variable phenotypes in women with X-linked AS. Therefore, the inactivation of a high proportion of normal X chromosomes in critical tissues could be clinically severe (11). In this study, skewed X was not detected in the peripheral blood cells of both patients 1 and 2. However, it remains possible that skewed X operates in specific tissue, namely the GBM, more strongly in patient 1 than in patient 2.

The mutation identified in our patient's family was c.2767G>C, resulting in a glycine to arginine substitution at position 923 in exon 32. Glycine substitutions are likely to alter the folding of the triple helix of collagen; however, solid evidence is absent regarding type IV collagen (12,13). Gross et al. proposed the following classification to link the phenotype and genotype (14):

i. Severe AS. Genotype alterations in COL4A5 include large rearrangement, premature stop codons, frameshift and donor splice site mutations, and mutations involving the NC1 domain. The phenotype is associated with the early onset of end-stage renal failure (ESRF) at -20 years of age, with 80% presenting with hearing loss and 40% presenting with ocular lesions.

ii. Moderate-severe AS. The genotype is characterized by non-glycine-X-Y missense, glycine-X-Y substitutions involving exons 21-47, and in-frame and acceptor splice site mutations. The phenotype is associated with ESRF at -26 years of age, with 65% presenting with hearing loss and 30% presenting with ocular lesions.

iii. Moderate AS. The genotype is characterized by glycine-XY substitutions involving exons 1-20. The phenotype is associated with ESRF at -30 years of age, with 70% presenting with hearing loss, and 30% presenting with ocular lesions.

According to this classification, our patients were classified as having moderate-severe AS. Taken together with no detection of skewed X, this may explain why our patients had no extrarenal symptoms. However, it would be clinically difficult to predict the prognosis of kidney function in women with AS due to the lack of genotype-phenotype correlations and the intra-familial heterogeneity of the phenotype (2). Therefore, our patients should be longitudinally followed while paying careful attention to a progressive increase in proteinuria, as previously suggested (2).

There is no specific treatment available for AS; however, early intervention with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) significantly delayed ESRD progression and improved life expectancy in X-linked AS (15,16). In women with X-linked AS, treatment with either ACEI or angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) inhibits progression to ESRD (15). Therefore, it is recommended that patients with X-linked AS are annually followed by a nephrologist, and treatment with ACEIs/ARBs should be initiated for patients with microalbuminuria, proteinuria, or hypertension (15,17). In our patients, ACEI (enalapril malate) was administered to patient 1 but not to patient 2, in whom a renal biopsy was performed 3 months after the delivery of her second child. We had to consider the potential high risk of fetal and newborn morbidity and mortality, which may be associated with ACEI/ARB fetopathy in pregnant women (18,19).

In conclusion, the identification of mutations and characteristic pathological findings were useful in making the diagnosis of AS. For a close long-term follow-up, the early detection and treatment of women with X-linked AS are important.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Mr. Satoshi Watanabe and Ms. Fumiko Kondo for their technical assistance, Dr. Shuichiro Watanabe for valuable advice, and Dr. Kimiko Ono for providing clinical information of the patients. A preliminary report was presented at the 45th Eastern Regional Meeting of the Japanese Society of Nephrology, 2015.

References

- 1. Alport AC. Hereditary familial congenital haemorrhagic nephritis. Br Med J 1: 504-506, 1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jais JP, Knebelmann B, Giatras I, et al. . X-linked Alport syndrome: natural history and genotype-phenotype correlations in girls and women belonging to 195 families: a “European Community Alport Syndrome Concerted Action” study. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2603-2610, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jais JP, Knebelmann B, Giatras I, et al. . X-linked Alport syndrome: natural history in 195 families and genotype- phenotype correlations in males. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 649-657, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barker DF, Denison JC, Atkin CL, Gregory MC. Efficient detection of Alport syndrome COL4A5 mutations with multiplex genomic PCR-SSCP. Am J Med Genet 98: 148-160, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Savige J, Ars E, Cotton RG, et al. . DNA variant databases improve test accuracy and phenotype prediction in Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 29: 971-977, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Allen RC, Zoghbi HY, Moseley AB, Rosenblatt HM, Belmont JW. Methylation of HpaII and HhaI sites near the polymorphic CAG repeat in the human androgen-receptor gene correlates with X chromosome inactivation. Am J Hum Genet 51: 1229-1239, 1992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rheault MN. Women and Alport syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol 27: 41-46, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimizu Y, Nagata M, Usui J, et al. . Tissue-specific distribution of an alternatively spliced COL4A5 isoform and non-random X chromosome inactivation reflect phenotypic variation in heterozygous X-linked Alport syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 1582-1587, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kubota T. A new assay for the analysis of X-chromosome inactivation in carriers with an X-linked disease. Brain Dev 23 (Suppl 1): S177-S181, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guo C, Van Damme B, Vanrenterghem Y, Devriendt K, Cassiman JJ, Marynen P. Severe alport phenotype in a woman with two missense mutations in the same COL4A5 gene and preponderant inactivation of the X chromosome carrying the normal allele. J Clin Invest 95: 1832-1837, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nakanishi K, Iijima K, Kuroda N, et al. . Comparison of alpha5(IV) collagen chain expression in skin with disease severity in women with X-linked Alport syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1433-1440, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Persikov AV, Pillitteri RJ, Amin P, Schwarze U, Byers PH, Brodsky B. Stability related bias in residues replacing glycines within the collagen triple helix (Gly-Xaa-Yaa) in inherited connective tissue disorders. Hum Mutat 24: 330-337, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raghunath M, Bruckner P, Steinmann B. Delayed triple helix formation of mutant collagen from patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Mol Biol 236: 940-949, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gross O, Netzer KO, Lambrecht R, Seibold S, Weber M. Meta-analysis of genotype-phenotype correlation in X-linked Alport syndrome: impact on clinical counselling. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1218-1227, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Temme J, Peters F, Lange K, et al. . Incidence of renal failure and nephroprotection by RAAS inhibition in heterozygous carriers of X-chromosomal and autosomal recessive Alport mutations. Kidney Int 81: 779-783, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gross O, Licht C, Anders HJ, et al. . Early angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in Alport syndrome delays renal failure and improves life expectancy. Kidney Int 81: 494-501, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Savige J, Gregory M, Gross O, Kashtan C, Ding J, Flinter F. Expert guidelines for the management of Alport syndrome and thin basement membrane nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 364-375, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Miura K, Sekine T, Iida A, Takahashi K, Igarashi T. Salt-losing nephrogenic diabetes insipidus caused by fetal exposure to angiotensin receptor blocker. Pediatr Nephrol 24: 1235-1238, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shotan A, Widerhorn J, Hurst A, Elkayam U. Risks of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition during pregnancy: experimental and clinical evidence, potential mechanisms, and recommendations for use. Am J Med 96: 451-456, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]