Abstract

We herein report the first case of pulmonary metastasis with lepidic growth that originated from cholangiocarcinoma. A 77-year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to exertional dyspnea and liver dysfunction. Computed tomography showed widespread infiltration and a ground-glass opacity in the lung and dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct. The pulmonary lesion progressed rapidly, and the patient died of respiratory failure. Cholangiocarcinoma and lepidic pulmonary metastasis were pathologically diagnosed by an autopsy. Lepidic pulmonary growth is an atypical pattern of metastasis, and immunopathological staining is useful to distinguish pulmonary metastasis from extrapulmonary cancer and primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: lepidic growth, lung metastasis, cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

The lung is a common site for metastasis. Multiple nodules or lymphangitic carcinomatosis are observed in the majority of cases of metastatic lung tumors (1-3). However, pulmonary metastasis sometimes presents uncommon radiographic features, making it difficult to distinguish the metastasis from primary lung cancer and other benign pulmonary diseases. These features include cavitation, calcification, hemorrhaging around metastatic nodules, pneumothorax, an air-space pattern, tumor embolism, endobronchial metastasis, dilated vessels within a mass, and sterilized metastasis (4). Of these radiographic features, an air-space pattern can occur when the tumor progresses along the alveolar wall, which is known as lepidic growth. Although lepidic tumor growth is typically observed in primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma, some reports have described cases of metastatic pulmonary adenocarcinoma from extrapulmonary organs, such as the gallbladder, pancreas, stomach, colon, and breast (5-7).

We herein report an autopsy case of lepidic pulmonary metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma, which was observed as a pulmonary air-space consolidation and ground-glass opacity on chest computed tomography (CT). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of lepidic pulmonary metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma.

Case Report

A 77-year-old Japanese man with progressing exertional dyspnea was admitted to our hospital. Prior to his first visit, the patient had been suspected to have cholangiocarcinoma according to laboratory results that included elevated transaminase, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels. Abdominal CT revealed thickening of the portal bile duct and dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 1A). However, no pathological evidence of carcinoma had yet been obtained at this point.

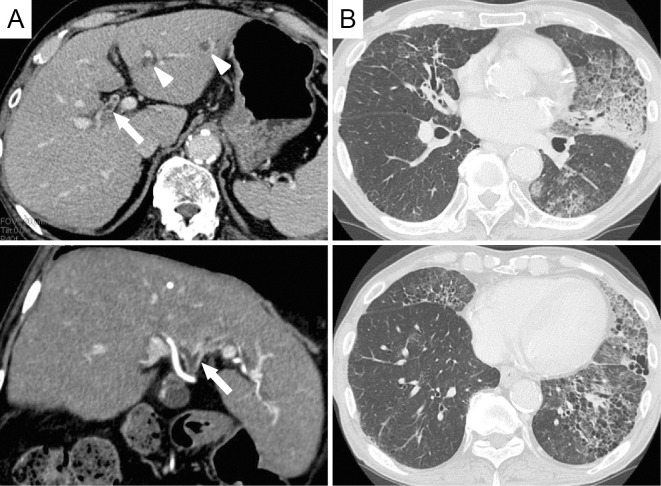

Figure 1.

Thickening of the portal bile duct (arrows) and dilation of the intrahepatic bile duct (arrowheads) are observed on computed tomography (CT) (A). Chest CT shows air-space consolidations and ground-glass opacities primarily in the left lung. A honeycomb change is also evident in the left lower lobe (B).

Chest auscultation revealed a fine crackle in his left lung, oxygen saturation of the peripheral artery was degraded to 94% at room air, and the patient was afebrile. Pulmonary CT revealed a widespread air-space consolidations and ground-glass opacities (Fig. 1B). A honeycomb change was also observed, mainly in the left lower lobe. This change had been previously observed on a CT scan conducted 6 months prior to the patient's first visit, suggesting that he had subclinical interstitial pneumonia.

Laboratory data on admission are presented in Table and revealed mild increases in the C-reactive protein (CRP) level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). However, leukocytosis was not apparent. Furthermore, (1,3)-β-D-glucan, Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6), pulmonary surfactant protein-D (SP-D), and immunoglobulin G (IgG) elevation were also observed. The bronchioloalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from the left upper pulmonary lobe exhibited increased alveolar neutrophils and lymphocytes (total: 336 cells/µL; macrophages: 38%, neutrophils: 40%, and lymphocytes: 22%). No microbes or atypical cells were detected in a BALF culture and cytological examination.

Table.

Laboratory Findings on Admission.

| Blood examination | Cre | 0.7 | mg/dL | ||

| WBC | 5,600 | /µL | Na | 132 | mEq/L |

| Neutrophils | 46.2 | % | K | 4.6 | mEq/L |

| Eosinophils | 1.1 | % | Cl | 98 | mEq/L |

| Basophils | 0.2 | % | CRP | 2.99 | mg/dL |

| Monocytes | 5.0 | % | CEA | 10.0 | ng/mL |

| Lymphocytes | 47.5 | % | CA19-9 | 372.3 | U/mL |

| RBC | 434×104 | /µL | KL-6 | 578 | U/mL |

| Hb | 12.4 | g/dL | SP-D | 256 | ng/mL |

| Plt | 11.4×103 | /µL | IgG | 3,460 | mg/dL |

| TP | 9.5 | g/dL | IgA | 661 | mg/dL |

| Alb | 3.4 | g/dL | IgM | 195 | mg/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.4 | mg/dL | (1,3)-β-D-glucan | 218.2 | pg/mL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.6 | mg/dL | ESR (60 min) | 62.0 | mm |

| AST | 68 | IU/L | ESR (120min) | 74.0 | mm |

| ALT | 78 | IU/L | BALF examination | ||

| LDH | 174 | IU/L | total cells | 336 | /µL |

| ALP | 1,167 | IU/L | macrophages | 38 | % |

| GGT | 465 | IU/L | neutrophils | 40 | % |

| BUN | 17.2 | mg/dL | lymphocytes | 22 | % |

According to these findings, we initially treated the patient as having pneumocystis pneumonia and/or acute exacerbation of pre-existing interstitial pneumonia using corticosteroid and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (SMX/TMP). SMX/TMP was discontinued since the elevated (1,3)-β-D-glucan level was due to a false positive result. Despite these intensive treatments, the lung infiltrates progressively expanded (Fig. 2).

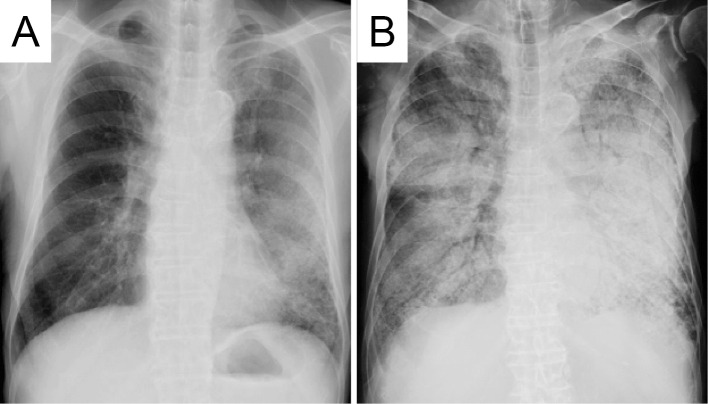

Figure 2.

A chest radiograph obtained on admission (A) and 3 months after admission (B). The rapid progression of bilateral infiltrative opacity is observed.

Although primary lung cancer was suspected due to the pattern of the infiltrates, best supportive care for putative lung cancer was provided because the performance status of this patient had degraded rapidly. He died of respiratory failure 3 months after admission.

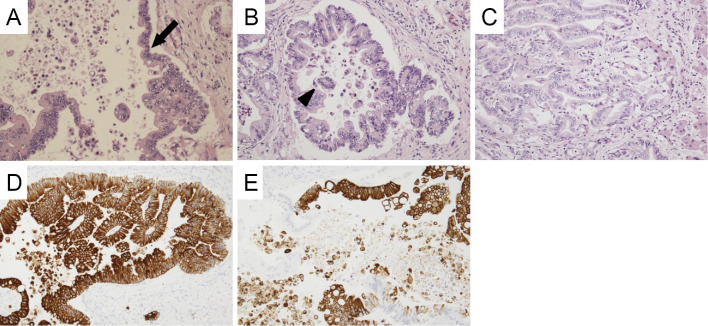

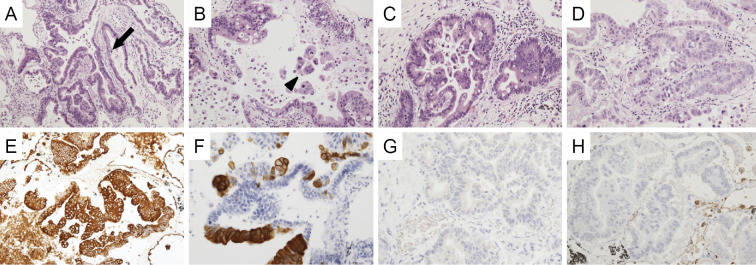

An autopsy was subsequently performed. In the hepatic hilus, 15 mm of solid mass was observed around the root of the left hepatic duct. Microscopically, atypical cells grew along the surface of the intrahepatic bile duct (Fig. 3A) and showed stromal invasion forming irregular tubular structures with or without papillary projection (Fig. 3B and C). Exfoliation of tumor clusters was evident in the lumens (Fig. 3C). The tumor showed positivity for cytokeratin 7 (CK7; Fig. 3D) and cytokeratin 20 (CK20; Fig. 3E) on immunostaining. These findings suggested a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, as had been previously suspected. Adenocarcinoma was also observed in the bilateral pulmonary lobes. Atypical cells were observed along the alveolar wall in most pulmonary areas (Fig. 4A and B). In resemblance with a liver tumor, stromal invasion of the carcinoma forming irregular tubular structures with or without papillary projection (Fig. 4C and D) was also found in the lung specimen. Additionally, a large number of tumor clusters were found in the alveolar cavity, suggesting transbronchial spread of adenocarcinoma (Fig. 4B). Although these findings were similar to those of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma, the tumor tissues that were observed in the lung specimen were morphologically very similar to cholangiocarcinoma that had been found in this patient. Furthermore, in resemblance with the liver specimen, both CK7 and CK20 were positive on immunostaining (Fig. 4E and F). Immunostaining with thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1; Fig. 4G) and Napsin-A (Fig. 4H) were additionally performed, both of which were negative in the pulmonary cancer lesion. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining showed that the tumors found in the liver and lung were rich in mucin production (Fig. 5A and E), and both tumors showed negativity for mucin2 (MUC2; Fig. 5B and F), focal positivity for mucin5Ac (MUC5Ac; Fig. 5C and G), and focal positivity for mucin6 (MUC6; Fig. 5D and H) upon immunostaining.

Figure 3.

Microscopic findings of the hepatic tumor. Adenocarcinoma is seen spreading along the bile duct wall (arrow) (A). The tumor shows stromal invasion forming irregular tubular structures with or without papillary projection (B, C). Exfoliation of carcinoma cell clusters (arrowhead) is observed in the ductal space (B). Carcinoma cells are diffusely positive for CK7 (D) and partially positive for CK20 (E).

Figure 4.

Microscopic findings of the lung tumor. Carcinoma cells proliferate along the alveolar septum (arrow) (A, B). Exfoliation of carcinoma cell clusters (arrowhead) is observed in the alveolar cavity (B). The tumor shows stromal invasion forming irregular tubular structures with or without papillary projection (C, D). Carcinoma cells are diffusely positive for CK7 (E) and partially positive for CK20 (F). Neither TTF-1 (G) nor Napsin A (H) expression is detected.

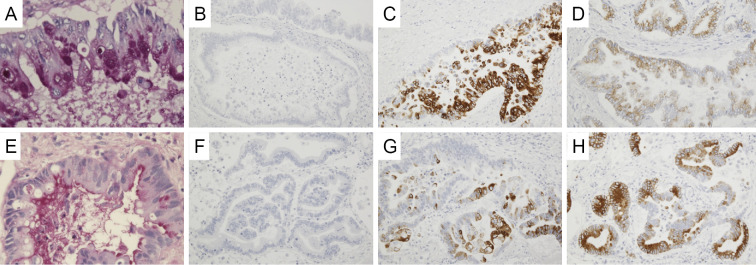

Figure 5.

Mucin staining of the hepatic tumor (A-D) and the lung tumor (E-H). PAS staining shows mucin production by the hepatic tumor (A) and the lung tumor (E). Both the hepatic tumor and the lung tumor show negativity for MUC2 (B, F) and focal positivity for MUC5Ac (C, G) and MUC6 (D, H).

No evidence supported the existence of an active fungal infection, including Pneumocystis jirovecii, in the lung specimen.

According to these histopathological findings, we finally diagnosed the patient with lepidic pulmonary metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma.

Discussion

Lepidic growth of cancer cells is a common pathological feature of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. However, pulmonary metastasis can also show lepidic growth, although it is rare. The lepidic growth of metastatic cancer is associated with radiological findings such as air-space nodules, consolidation containing an air bronchogram, focal or extensive ground-glass opacities, and nodules with halo signs (4). These radiological features of lepidic metastasis also resemble those of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma that shows lepidic growth.

Some case reports have described lepidic pulmonary metastasis from adenocarcinoma of extra-thoracic organs, such as of the gallbladder, pancreas, stomach, colon, and breast (5-8). In addition to the pulmonary metastasis of adenocarcinoma, the pulmonary metastasis of malignant melanoma can also show pathologically lepidic growth in the lung (9). In a previous case series, approximately 10% of cases with an air-space pattern on a chest CT scan were identified as metastatic adenocarcinomas. However, that series only included 1 case in which pancreatic carcinoma was pathologically shown to have undergone lepidic pulmonary metastasis (8).

In the present case, metastatic lung cancer from cholangiocarcinoma was strongly suspected because the pathological features observed in the lung tumor were closely related to those observed in the bile duct tumors. For the purpose of further examination, several immunostainings were performed. Immunostaining with CK7 and CK20 is commonly used to estimate the origin of carcinoma. A previous report has demonstrated that 90% of pulmonary adenocarcinomas show a CK7+/CK20- pattern, whereas 43% of cholangiocarcinoma show a CK7+/CK20+ pattern (10). Furthermore, TTF-1 and Napsin-A have been reported to show high rates of positivity (73% and 83%, respectively) (11) in primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. According to these data, metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma is more compatible for the diagnosis of the present patient than primary lung cancer because immunostaining of the lung tumor showed the CK7+/CK20+ pattern, as well as negativity for TTF-1 and Napsin-A. The similarities in the MUC2, MUC5Ac, and MUC6 expression also support this diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first to describe a case of lepidic pulmonary metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma. Similar to some previous cases (7,9), lepidic pulmonary metastasis progressed rapidly in the present case, which might be partially explained by rapid intrabronchial tumor transition. Indeed, pathologically, many tumor clusters were observed in the alveolar space of the patient's lung specimen. In cases of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma, aerogenous tumor spread is known to indicate a poor prognosis (12). Additionally, in cases of pulmonary metastasis, a rapid progression may be implied by the histopathologic features of exfoliations of tumor clusters in the alveolar space.

In conclusion, we presented a case of rapidly progressed lepidic pulmonary metastasis from cholangiocarcinoma. Radiological and histopathological features of lepidic pulmonary metastasis may resemble those of primary adenocarcinoma. A pathological differential diagnosis should thus be performed early and include immunostaining.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Davis SD. CT evaluation for pulmonary metastases in patients with extrathoracic malignancy. Radiology 180: 1-12, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hirakata K, Nakata H, Nakagawa T. CT of pulmonary metastases with pathological correlation. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 16: 379-394, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Libshitz HI, North LB. Pulmonary metastases. Radiol Clin North Am 20: 437-451, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, Chung MJ, Kim MY. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics 21: 403-417, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster CS. Mucus-secreting ‘alveolar-cell' tumour of the lung: a histochemical comparison of tumours arising within and outside the lung. Histopathology 4: 567-577, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenblatt MB, Lisa JR, Collier F. Primary and metastatic bronciolo-alveolar carcinoma. Dis Chest 52: 147-152, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tokunaga T, Arakawa H, Kuwashima Y. A case of lepidic pulmonary metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder mimicking acute interstitial pneumonia. Clin Radiol 60: 1213-1215, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaeta M, Volta S, Scribano E, Loria G, Vallone A, Pandolfo I. Air-space pattern in lung metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the GI tract. J Comput Assist Tomogr 20: 300-304, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okita R, Yamashita M, Nakata M, Teramoto N, Bessho A, Mogami H. Multiple ground-glass opacity in metastasis of malignant melanoma diagnosed by lung biopsy. Ann Thorac Surg 79: e1-e2, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chu P, Wu E, Weiss LM. Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol 13: 962-972, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bishop JA, Sharma R, Illei PB. Napsin A and thyroid transcription factor-1 expression in carcinomas of the lung, breast, pancreas, colon, kidney, thyroid, and malignant mesothelioma. Hum Pathol 41: 20-25, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clayton F. Bronchioloalveolar carcinomas. Cell types, patterns of growth, and prognostic correlates. Cancer 57: 1555-1564, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]