Abstract

A 59-year-old woman, diagnosed with advanced rectal cancer, presented with a low-grade fever and dyspnea on exertion after the 2nd cycle of TAS-102. TAS-102 has promising efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. A CT scan revealed mosaic patterns with bilateral ground-glass opacities. The drug lymphocyte stimulation test for TAS-102 was strongly positive and serum β-D glucan level was elevated. The clinical course was compatible with TAS-102-induced pneumonitis combined with pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). We herein report a rare case of drug-induced pneumonitis in a patient receiving TAS-102 in combination with PCP.

Keywords: TAS-102, pneumonitis, colorectal cancer, pneumocystis pneumonia

Introduction

TAS-102 (Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) is a novel oral nucleoside antitumor agent consisting of trifluridine (FTD) and tipiracil hydrochloride (TPI) at a molar ratio of 1:0.5. FTD is the active antitumor component of TAS-102. The monophosphate form of FTD inhibits thymidylate synthase, and its triphosphate form is incorporated into DNA in tumor cells, which mediates its antitumor effects (1). In an international multicenter randomized double-blind phase III study, treatment with TAS-102 resulted in a significant improvement in the overall and progression-free survival and exhibited a manageable safety profile relative to placebo in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapies (2). TAS-102 was approved in Japan in March 2014 and has been frequently used in certain patient subpopulations, and it was recently approved for use in the United States in December 2015. The approval is currently underway in other foreign countries. Common side effects include neutropenia, leucopenia, anemia, fatigue, and diarrhea. There has been no report of TAS-102-induced severe lung toxicity (1,2). In this report, we present a case of severe pulmonary infiltration caused by TAS-102.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman had been treated for stage IV rectal cancer three years prior to the study. The patient had no significant cardiac or smoking history. The cancer possessed a KRAS mutation at codon 13, and distant metastases were present in the lungs. A combination of bevacizumab and capecitabine with or without oxaliplatin dependent on peripheral neurotoxicity was administered as first-line chemotherapy for 43 cycles. A partial remission was achieved, and the patient's cancer relapsed. The patient gradually developed pain in the buttocks. Palliative radiotherapy was used to control her pain. The total irradiation dose was 36 Gy, divided into 12 fractions, and was centered on the rectum. Her loss of appetite worsened because of pain secondary to tumor progression, despite irradiation. We administered betamethasone (1.5 mg/day) to control her symptoms. To avoid alopecia, the treatment regimen was switched to TAS-102 as second-line therapy. A dose of 35 mg/m2 TAS-102 was taken orally twice a day over a 28-day cycle: a 2-week cycle of 5 days of treatment followed by a 2-day rest period, and then a 14-day rest period. Three days after the 1st cycle of TAS-102 therapy, she developed a low-grade fever with neutropenia of grade 2 (1,500/mm3) in the absence of dyspnea and chest X-rays showed no infiltrates. We administered empirical levofloxacin (LVFX). Her symptoms improved after LVFX for 5 days. The therapy was continued for 2 cycles. Over the course of TAS-102 therapy, the thickness of the primary site was reduced on the chest computed tomography (CT) scan, and the patient's pain improved. After the 2nd cycle of TAS-102, the dose of 240 mg/day oxycodone hydrochloride for pain relief was reduced to 180 mg/day. Accordingly, we considered TAS-102 to be effective.

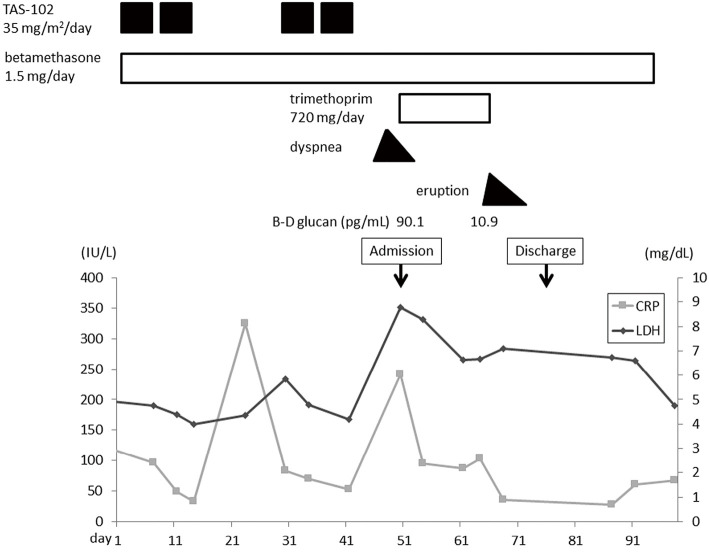

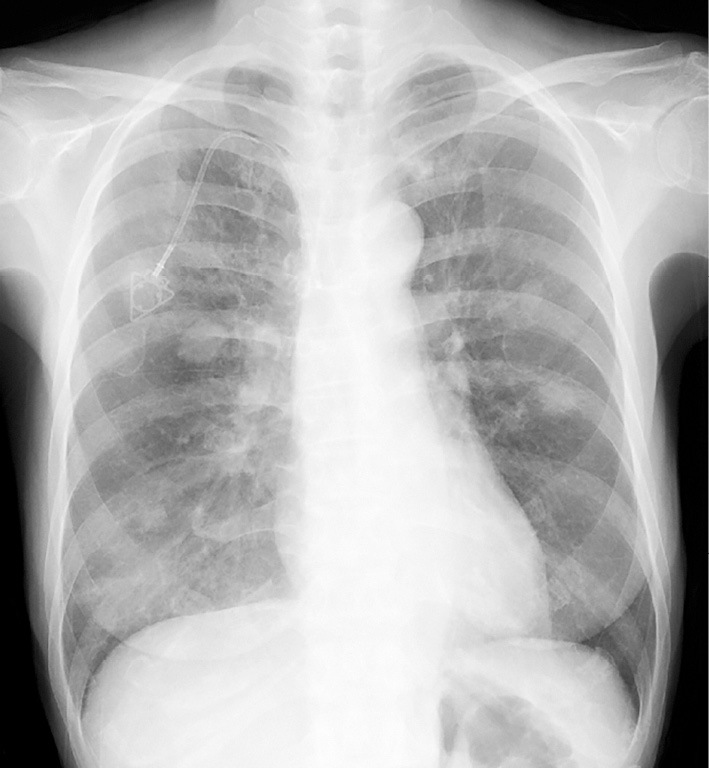

Nine days after the 2nd cycle of TAS-102 therapy, the patient developed a low-grade fever and dyspnea on exertion (DOE). Four days later, the patient presented to our clinic with a persistent fever and dyspnea. Her height was 151 cm and weight was 35 kg. Her body temperature was 37.9℃, oxygen saturation was 92% on room air, and respiratory rate was 16/min. Although no crackles, wheezes, or rhonchi were present by chest auscultation of both lung fields, chest X-rays revealed bilateral infiltrative shadows (Fig. 1). A further investigation by a CT scan revealed mosaic patterns with bilateral ground-glass opacities (GGOs) (Fig. 2), which were not detected just before the administration of TAS-102. A cardiac exam was normal. The white blood cell count was 2,700/mm3, with 66.8% neutrophils, 25.3% lymphocytes, 7.5% monocytes and 0.2% eosinophils. The serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were elevated at 6.05 mg/dL and 351 IU/L, respectively. Liver and renal functions were normal. The serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was also elevated at 23.0 ng/mL, and Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) levels (<500 U/mL) were 375.3 U/mL. Aspergillus, Candida and cytomegalovirus antigen tested negative. Urine antigen testing for Legionella pneumophila and throat swab testing for Streptococcus pneumoniae were also negative. The results of arterial blood gas analyses on room air were partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2) of 68.5 mmHg, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) of 43.3 mmHg, and pH of 7.441, suggesting that the alveolar-arterial oxygen difference had increased. We administered oxygen at 2 L/min via a nasal cannula. Pneumonitis was suspected, and the patient was admitted to our hospital on the same day.

Figure 1.

A chest X-ray taken on admission. Diffuse infiltrative shadows can be observed in both lung fields.

Figure 2.

A chest CT scan on admission reveals mosaic patterns with bilateral ground-glass opacities and multiple nodular metastatic lesions.

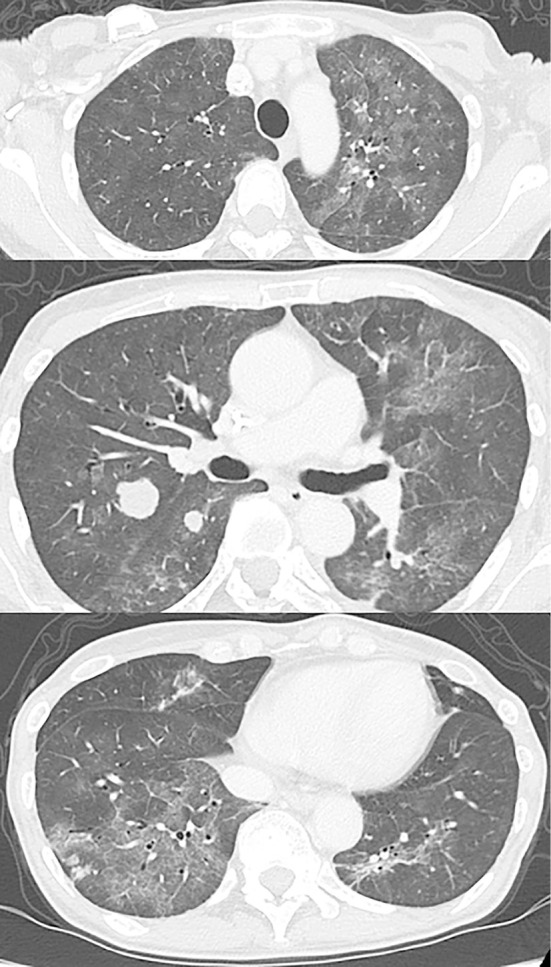

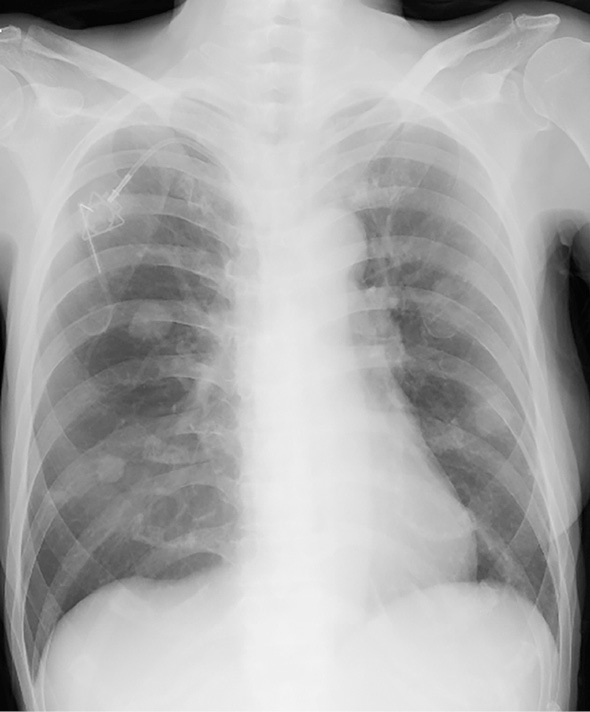

Retrospectively, the patient's serum CRP and LDH levels were moderately elevated in the rest period of the 1st cycle of TAS-102, and these data improved prior to the 2nd cycle (Fig. 3). Dyspnea and a low-grade fever appeared four days before hospitalization and were gradually improved by the day of hospitalization. According to these findings, we suspected drug-induced interstitial pneumonia, however, it was not possible to rule out infectious pneumonitis, such as pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), because TAS-102 can cause immunosuppression. We recommended bronchoscopy to make a definitive diagnosis, however, the patient strongly refused. We started trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX, trimethoprim 720 mg/day) to cover PCP. As her dyspnea had not deteriorated on admission compared with the onset, betamethasone at 1.5 mg/day was not increased. Two days after the administration of TMP-SMX and continuous betamethasone, the diffuse infiltrative shadows on her chest X-ray decreased (Fig. 4), and the respiratory failure recovered. The patient's serum β-D glucan level on admission was significantly elevated at 90.1 pg/mL. A drug lymphocyte stimulation test (DLST) for TAS-102 was strongly positive (1,289 cpm, stimulation index 332; normal range: lower 180) and that for LVFX was negative (399 cpm, stimulation index 102). According to these findings, the patient was diagnosed with TAS-102-induced pneumonitis complicated with PCP. Two weeks after the administration of TMP-SMX, skin eruptions developed on her precordium that rapidly spread to her trunk and femoral region with a low-grade fever. TMP-SMX was immediately stopped, and the symptoms resolved. Her serum level of β-D glucan was gradually decreased after a 2-week administration of TMP-SMX.

Figure 3.

Clinical course of the patient. Day 1 is the starting date of the first cycle of TAS-102.

Figure 4.

A chest X-ray demonstrating diffuse infiltrative shadows that almost completely disappeared after treatment.

Discussion

There has been limited information regarding the safety of TAS-102 monotherapy. Post-marketing surveillance of the safety profile of TAS-102 in 3,373 Japanese patients with colorectal cancer was carried out for 6 months from May to November 2014 during an international multicenter randomized double-blind phase III study (2). The incidence rate of total and serious pneumonitis was 0.2% (7 patients). This case report presents a rare case of pneumonitis in a patient receiving TAS-102 for rectal cancer.

According to a statement for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced lung injuries by the Japanese Respiratory Society (3), the following five conditions must be met to diagnose drug-induced lung injuries: 1) a history of ingestion of a drug, 2) the clinical manifestations were reported to be induced by a drug, 3) other causes of the clinical manifestations could be ruled out, 4) clinical courses showed improvement of the clinical manifestations after drug discontinuation, and 5) clinical courses showed exacerbation of the clinical manifestation after resuming drug administration. In the present case, TAS-102 was suspected to be the causative drug of pneumonitis according to the clinical course of drug administration. The patient did not exhibit respiratory symptoms related to pneumonitis in the 1st cycle of TAS-102. In retrospect, the patient's serum CRP and LDH levels were moderately elevated with a low-grade fever during the rest period of the 1st cycle. The elevated serum CRP and LDH levels improved before the 2nd cycle. Rechallenge with the causative drug for drug-induced interstitial lung disease (ILD) is not recommended. In the present case, we accidentally administered a 2nd cycle of TAS-102. After administering the subsequent round of TAS-102, the patient's serum CRP and LDH levels increased with dyspnea and a high fever. The drug retest confirmed that the pneumonitis was TAS-102-induced lung disease.

Moreover, the results of the DLST for TAS-102 were positive on admission. The DLST is generally used to identify allergy-inducing drugs (4,5). There is currently insufficient in vivo data of the DLST for TAS-102, and we have to consider that a false positive reaction may occur. Kawabata et al. reported that the DLST could show a false positive response through an intracellular function that accelerates thymidine incorporation in lymphocytes by the salvage pathway after inhibition of DNA de novo synthesis caused by 5-FU derivative anticancer therapy, including S-1 (6). FTD can inhibit thymidylate synthase (TS), but FTD-dependent inhibition of TS is reversible. The washout time of 5-FU derivative drugs is between 6 and 24 hours in previous experiments (7). The present patient developed pneumonitis 12 days after TAS-102 medication. Accordingly, the positive results of the DLST may further support the notion that TAS-102 induced lung injury.

To meet all conditions of the diagnostic criteria of drug-induced lung injuries, we have to consider differential causes which might have induced pneumonitis in the present case. A sudden onset of bilateral patchy lung GGOs on a chest CT scan implies pneumonitis complicated by infectious diseases. The most likely infectious causes, such as atypical and viral pneumonia, were excluded by negative test results. In addition, the serum level of β-D glucan was elevated at 90.1 pg/mL in this case. The (1-3)-β-D glucan assay is a useful marker to detect invasive fungal infection, including PCP. There have been several meta-analyses describing the usefulness of β-D glucan for PCP diagnosis (8,9). Tasaka et al. reported that the cut-off level for β-D glucan in PCP is 31.1 pg/mL according to a receiver operating characteristics curve analysis (7,10). Invasive aspergillosis or systemic candidiasis is also a common cause of elevated β-D glucan; however, Aspergillus and Candida antigens were negative in the present patient. Furthermore, the patient's dyspnea and fever tended to be improved with the withdrawal of TAS-102 and resolved after TMP-SMX and continuous steroid administration. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient with TAS-102-induced pneumonitis combined with PCP according to her symptoms and chest CT findings, without the detection of P. jirovecii DNA. This is the limitation of our report.

PCP has been reported to occur in patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy for solid malignancies, but it is relatively rare for those undergoing standard-dose chemotherapy (11). Standard-dose chemotherapy and intermittent chemotherapy-related corticosteroids as premedication for lung cancer are considered to be risk factors for PCP (12). Particular attention should be paid if the corticosteroid administration is equivalent to 20 mg of prednisolone per day and continues for more than 4 weeks (13). The dose and duration of betamethasone used in this patient to reduce appetite loss was 1.5 mg for 100 days. The immunosuppressive effects of TAS-102 and comparative high dose of corticosteroids may have influenced the development of PCP, which is difficult to distinguish from ILD. The report of combined PCP and ILD with standard cytotoxic chemotherapy is rare (14). When pneumonitis is encountered in patients such as ours, PCP should be considered in the differential diagnosis, and physicians should perform appropriate diagnostic tests to distinguish between PCP and ILD.

TAS-102 is an increasingly common treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. This case report illustrated a rare, but serious side effect associated with TAS-102 therapy. Clinicians must be aware of this condition to prevent further morbidity and mortality in these cancer patients.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Yoshino T, Mizunuma N, Yamazaki K, et al. . TAS-102 monotherapy for pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 13: 993-1001, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, et al. . Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 372: 1909-1919, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kubo K, Azuma A, Kanazawa M, et al. . Consensus statement for the diagnosis and treatment of drug-induced lung injuries. Respir Investig 51: 260-277, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pichler WJ, Tilch J. The lymphocyte transformation test in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity. Allergy 59: 809-820, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matsuno O. Drug-induced interstitial lung disease: mechanisms and best diagnostic approaches. Respir Res 13: 39, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kawabata R, Koida M, Kanie S, Tanaka G, Ohuchida A, Yoshida T. DLST as a method for detecting TS-1-induced allergy. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho (Japanese Journal of Cancer and Chemotherapy) 33: 345-348, 2006(in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tanaka N, Sakamoto K, Okabe H, et al. . Repeated oral dosing of TAS-102 confers high trifluridine incorporation into DNA and sustained antitumor activity in mouse models. Oncol Rep 32: 2319-2326, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karageorgopoulos DE, Qu JM, Korbila IP, Zhu YG, Vasileiou VA, Falagas ME. Accuracy of β-D-glucan for the diagnosis of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia: a meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 19: 39-49, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Onishi A, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of serum 1,3-β-D-glucan for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, invasive candidiasis, and invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol 50: 7-15, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tasaka S, Hasegawa N, Kobayashi S, et al. . Serum indicators for the diagnosis of pneumocystis pneumonia. Chest 131: 1173-1180, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Varthalitis I, Aoun M, Daneau D, Meunier F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with cancer. An increasing incidence. Cancer 71: 481-485, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mori H, Ohno Y, Ito F, et al. . Polymerase chain reaction positivity of Pneumocystis jirovecii during primary lung cancer treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 40: 658-662, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sepkowitz KA. Opportunistic infections in patients with and patients without Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 34: 1098-1107, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yano S. S-1-induced lung injury combined with pneumocystis pneumonia. BMJ Case Rep 2013: 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]