Abstract

Background

Airway inflammation is a significant contributor to the morbidity of cystic fibrosis (CF) disease. One feature of this inflammation is the production of oxygenated metabolites, such as prostaglandins. Individuals with CF are known to have abnormal metabolism of fatty acids, typically resulting in reduced levels of linoleic acid (LA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

Methods

This is a randomized, double-blind, cross-over clinical trial of DHA supplementation with endpoints of plasma fatty acid levels and prostaglandin E metabolite (PGE-M) levels. Patients with CF age 6 to 18 years with pancreatic insufficiency were recruited. Each participant completed 3 four-week study periods: DHA at two different doses (high dose and low dose) and placebo with a minimum 4 week wash-out between each period. Blood, urine, and exhaled breath condensate (EBC) were collected at baseline and after each study period for measurement of plasma fatty acids as well as prostaglandin E metabolites.

Results

Seventeen participants were enrolled, and 12 participants completed all 3 study periods. Overall, DHA supplementation was well tolerated without significant adverse events. There was a significant increase in plasma DHA levels with supplementation, but no significant change in arachidonic acid (AA) or LA levels. However, at baseline, AA levels were lower and LA levels were higher than previously reported for individuals with CF. Urine PGE-M levels were elevated in the majority of participants at baseline, and while levels decreased with DHA supplementation, they also decreased with placebo.

Conclusions

Urine PGE-M levels are elevated at baseline in this cohort of pediatric CF patients, but there was no significant change in these levels with DHA supplementation compared to placebo. In addition, baseline plasma fatty acid levels for this cohort showed some difference to prior reports, including higher levels of LA and lower levels of AA, which may reflect changes in clinical care, and consequently warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Fatty acids, Cystic Fibrosis, DHA, Prostaglandin E

Introduction

Airway inflammation is a major contributor to poor clinical outcomes in individuals with cystic fibrosis(CF) (1). Several studies have shown that markers of inflammation are elevated in the sputum of individuals with CF, including neutrophil elastase and IL-8 (2, 3); while markers of inflammation resolution, such as lipoxin A4, are decreased (4). Individuals with CF also display abnormalities of fatty acid (FA) metabolism, most notably characterized by decreased linoleic acid (LA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) levels (5, 6). Research completed in both animals and humans has shown that these FA abnormalities may be related to increased inflammation through increased prostaglandin production (7, 8). In cell culture and animal models, DHA supplementation has been shown to reverse abnormal PUFA metabolism and some aspects of CF pathology, but results in human trials have been less clear (7, 9–11).

This short-communication briefly describes a double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over clinical trial to detect changes in prostaglandin metabolites in pediatric patients with CF who were receiving DHA supplementation.

Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial of DHA supplementation. There were 3 study periods, each of 4 weeks duration: high-dose DHA (35mg/kg/day), low-dose DHA (25mg/kg/day), and placebo. A minimum 4-week wash-out period occurred between each of the three study periods. Study capsules were provided by Martek Bioscience Corp., USA. The DHA supplement was in triglyceride form from a microalgal source and the placebo was high oleic acid sunflower oil. Participants were randomized to a specific sequence of the three study periods and participants were instructed to take the study capsules as a single daily dose.

Participants

Individuals with CF greater than or equal to 6 years of age and less than 18 years of age were eligible. Individuals also needed to have a baseline forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of greater than 40% predicted. Exclusion criteria included: CF-related diabetes, CF-related liver disease, consideration for lung transplantation, active pulmonary exacerbation, history of fish allergy, daily chronic use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), use of anticoagulant drugs, or chronic use of glucocorticoids.

Participants were recruited from a single pediatric CF center. All pediatric participants gave informed assent and parents gave informed consent prior to enrollment. The study was approved by the institutional review board (#081363) and the study is listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00924547).

Study period measurements

Endpoints included plasma fatty acid levels, urine prostaglandin-E metabolite (PGE-M), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) measured in exhaled breath condensate (EBC). These were collected at baseline and after each of the three study periods. Weight and height were obtained at each study visit as a measure of patient safety, not a clinical endpoint.

Plasma fatty acids were obtained from lipid extraction and methylation by methods previously described (12). Fatty acids were identified and quantified by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) and reported as %mole. Urine PGE-M was quantified in the Vanderbilt Eicosanoid Core Laboratory by methods previously described (8). Urine PGE-M levels were reported as ng/mg Cr. EBC was collected using RTube™ (Respiratory Research, Inc.) with patients being instructed to do tidal breathing for 5–7 minutes.

Statistical Considerations

Sample size and power estimates were made using the PS program (Nashville, TN). Using a sample size of 13 patients and cross-over study design, the study has a 90% power to detect a 15 point difference in mean 8-isoprostane PGF2α between groups. To account for drop-out the goal enrollment was set at 18 patients.

Results

There were 17 participants enrolled in the study, 12 of which completed all study periods. Two participants withdrew before the completion of the first study period due to dislike of capsule taste, one withdrew after being admitted for constipation following a single dose of study capsule, and one withdrew after completion of the first study period due to diagnosis of CF-related diabetes on a routine oral glucose tolerance test. The participants were at their clinical baseline at time of enrollment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics (n=17 individuals). Continuous variables are expressed as median with inter-quartile range (IQR). Inpatient and outpatient pulmonary exacerbations were determined by chart review documentation.

| Female (n, %) | 6, 35% |

| Age (years) | 10 [7, 13] |

| Genotype (n, %) | |

| ΔF508 homozygous | 10, 59% |

| ΔF508 heterozygous | 6, 35% |

| FEV1 % predicted at enrollment | 101 [92, 107] |

| BMI percentile at enrollment | 54 [40, 63] |

| Inpatient pulmonary exacerbations in year prior to enrollment | 1 [0, 2] |

| Outpatient antibiotic courses for pulmonary exacerbations in year prior to enrollment | 1 [0, 2] |

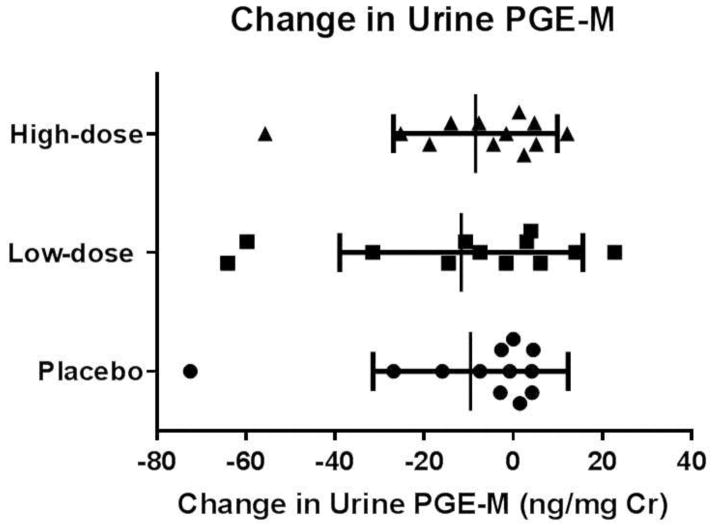

At baseline, study participants had elevated urine PGE-M levels with a median value of 25 ng/mg Cr (normal previously reported as less than 10 ng/mg Cr (8)). There was a decrease in urine PGE-M with both high and low doses of DHA supplementation (median decreases of 8 ng/mg Cr and 14 ng/mg Cr, respectively). However, there was also a decrease in PGE-M levels by a median value of 8 ng/mg Cr with the placebo (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Change in urine prostaglandin E metabolite (PGE-M). Data are displayed for the 12 participants who completed all study arms as individual change in PGE-M from baseline measurements. Study groups are displayed as high-dose DHA supplementation, low-dose DHA supplementation, and placebo. Statistical testing by Friedman Test. No statistical significance in the change in urine PGE-M was observed between the three treatment groups.

Plasma FA levels were reported as mole percent (Table 3). At baseline, participants had low plasma DHA levels (median 0.33 mole percent). After DHA supplementation, participants in both the high-dose and low-dose DHA supplementation arms displayed significant increases in plasma DHA compared to baseline. There was not a significant difference in plasma DHA between low and high-dose supplementation. Baseline LA levels were higher than previously reported for individuals with CF (5) (median 25.73 mole percent) and there was no significant change in LA with DHA supplementation. In addition, there was no significant change in arachidonic acid (AA) or mead acid levels with DHA supplementation. AA levels were lower at baseline than previously reported (5). The triene/tetraene ratio (mead acid/arachidonic acid) was normal at baseline (13) and did not change with DHA supplementation.

Several fatty acids showed small absolute changes which reached statistical significance (eicosanoic acid, 20:1 n-9, baseline vs. placebo; eicosadienoic acid, 20:2 n-6, low-dose vs. high dose; and adrenic acid, 22:4 n-6, baseline vs. high-dose), but clinical significance is unknown. Hexadecanoic acid (16:0) levels decreased with low dose DHA supplementation, but not high dose supplementation.

Due to technical issues with EBC collection, including a small volume of exhaled breath collected, PGE2 or 8-isoprostane PGF2α levels were not able to be measured.

Discussion

This pilot study demonstrated decreased PGE-M levels with DHA supplementation, but a placebo effect was also observed. Plasma DHA levels increased in the blood with oral DHA supplementation, but there were not clinically meaningful changes in other FAs including LA, mead acid, or AA. Elevated baseline urine PGE-M levels and changes in baseline plasma fatty acid levels were also observed. These baseline changes were observed despite a good clinical baseline, that was representative of the majority of children in our center (2014 median FEV1 for our center for 6–17 year olds was 98.2% predicted and the median BMI percentile for the same age group was 62.5%).

There is a great need for validated biomarkers for pediatric CF therapeutic trials (14). Many children with CF have good lung function (15), making detection of benefit difficult in short clinical trials. This clinical trial examined markers of inflammation that related to FA metabolism, specifically prostaglandins, which are metabolites of AA. Urine PGE-M is a relatively new biomarker, but it has been shown previously to be elevated in adults with CF and to have a dose effect with CF genotype severity (8). PGE-M is an attractive potential biomarker because it can easily be obtained from the urine, but further research is needed to better characterize baseline values in CF population.

Similar to previous studies, we demonstrated it is possible to increase plasma DHA levels with supplementation in pediatric CF participants without significant adverse events (11, 16–20). We did not observe a significant increase in LA levels, despite a somewhat higher level of LA in the placebo, or a significant decrease in AA levels with DHA supplementation and consequently we concluded that one month DHA supplementation did not have a substantial effect on clinically meaningful FA levels.

However, there were notable differences in baseline values of clinically meaningful fatty acids in comparison to previous reports. LA levels were higher than previously reported for pediatric CF patients (21–23). This could explain why an increase in LA levels was not seen with DHA supplementation. Arachidonic acid levels were lower than previously seen in the same reports. Furthermore, the presence of essential FA deficiency, as demonstrated by an elevated triene/tetraene (T/T) ratio, has been well documented in individuals with CF, including pediatric patients at baseline (24). In our cohort, however, we observed a normal T/T ratio at baseline and throughout all study points. Taken together, these FA results suggest that previously reported observations of decreased LA, increased mead acid, and elevated AA may no longer be true in a new generation of pediatric CF patients. Part of the explanation for these observations could be a reflection of changes in treatment practice, including nutrition interventions (15) that seek a higher BMI and overall improved lung function in pediatric CF patients. These observations warrant further investigation.

Limitations of this study include the short duration of treatment and that it was completed at a single site pediatric CF center. This study was not powered to detect changes in clinical endpoints or in urine PGE-M. Furthermore, urine PGE-M values have not yet been definitively correlated with clinical endpoints, and further research is needed to elucidate this relationship.

In conclusion, we found elevated baseline levels of a prostaglandin metabolite, urine PGE-M, in a cohort of pediatric CF patients at their clinical baseline. After DHA supplementation, there was a decrease in urine PGE-M, but we also observed a placebo effect. DHA supplementation also did not appear to change clinically relevant plasma fatty acid levels such as linoleic acid and arachidonic acid; however, baseline fatty acid profiles demonstrated some differences when compared to previous reported levels. These observations warrant further research, particularly considering the potential utility of urine PGE-M as a CF biomarker.

Table 2.

Plasma fatty acid levels. Each fatty acid is expressed in units of mole percent and data are displayed as a median with inter-quartile range (IQR). Statistical testing by Friedman Test with correct for pair-wise comparisons. Statistical significance denoted by * where p<0.05.

| Fatty Acid | Baseline | Placebo | Low-Dose | High-Dose | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetradecanoic acid (14:0) | 0.96 [0.66, 1.09] | 0.82 [0.52, 0.98] | 0.86 [0.51, 1.04] | 0.64 [0.47, 0.78] | 0.73 |

| Hexadecanoic acid (16:0) | 30.08 [26.75, 31.87] | 28.73 [23.03, 29.83] | 28.05 [25.96, 29.56] | 27.45 [24.91, 30.31] | 0.02 * |

| Palmitoleic acid (16:1) | 1.08 [0.7, 2.25] | 1.14 [0.72, 2.55] | 1.21 [0.73, 1.83] | 1.17 [0.73, 1.94] | 0.96 |

| Octadecanoic acid (18:0) | 11.6 [10.27, 12.33] | 10.65 [10.0, 11.3] | 11.22 [10.31, 11.96] | 11.39 [10.55, 12.19] | 0.08 |

| Oleic acid (18:1 n-9) | 9.46 [8.21, 10.93] | 10.72 [9.27, 13.02] | 9.36 [7.47, 10.88] | 8.98 [7.88, 10.8] | 0.08 |

| Vaccenic acid (18:1 n-7) | 13.26 [12.24, 15.85] | 14.66 [12.83, 16.65] | 13.82 [12.01, 16.05 | 13.55 [11.43, 15.54] | 0.64 |

| Linoleic acid (18:2 n-6; LA) | 25.73 [23.89, 29.69] | 25.91 [22.47, 30.32] | 28.40 [23.77, 30.88] | 27.76 [25.01, 29.53] | 0.04 |

| Gamma-linolenic acid (18:3 n-6) | 0.15 [0.09, 0.28] | 0.18 [0.14, 0.23] | 0.18 [0.16, 0.29] | 0.15 [0.09, 0.23] | 0.66 |

| α-linolenic acid (18:3 n-3) | 0.22 [0.12, 0.53] | 0.28 [0.11, 0.68] | 0.31 [0.14, 0.49] | 0.26 [0.16, 0.38] | 0.87 |

| Eicosanoic acid (20:0) | 0.07 [0.05, 0.08] | 0.06 [0.05, 0.11] | 0.07 [0.06, 0.09] | 0.07 [0.05, 0.10] | 0.61 |

| Eicosenoic acid (20:1 n-9) | 0.10 [0.07, 0.14] | 0.14 [0.11, 0.19] | 0.14 [0.10, 0.18] | 0.10 [0.08, 0.14] | 0.03* |

| Eicosadienoic acid (20:2 n-6) | 0.05 [0.04, 0.08] | 0.07 [0.04, 0.11] | 0.09 [0.08, 0.12] | 0.06 [0.04, 0.08] | 0.03* |

| Mead acid (20:3 n-9) | 0.06 [0.04, 0.08] | 0.05 [0.04, 0.08] | 0.06 [0.04, 0.09] | 0.06 [0.05, 0.08] | 0.57 |

| Dihomo-gamma- linolenic acid (20:3 n-6) | 1.09 [0.82, 1.44] | 1.03 [0.91, 1.33] | 0.91 [0.82, 1.35] | 0.94 [0.63, 1.28] | 0.44 |

| Arachidonic Acid (20:4 n-6; AA) | 3.30 [2.72, 4.48] | 3.43 [2.80, 3.67] | 3.60 [2.89, 3.99] | 3.27 [3.00, 4.34] | 0.31 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5 n-3) | 0.13 [0.07, 0.17] | 0.12 [0.07, 0.21] | 0.16 [0.15, 0.20] | 0.20 [0.13, 0.27] | 0.02 |

| Adrenic acid (22:4 n-6) | 0.08 [0.04, 0.10] | 0.07 [0.06, 0.08] | 0.06 [0.04, 0.09] | 0.05 [0.03, 0.08] | 0.009* |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5 n-6) | 0.04 [0.02, 0.05] | 0.04 [0.02, 0.08] | 0.10 [0.07, 0.14] | 0.11 [0.07, 0.20] | 0.0003* |

| Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5 n-3) | 0.12 [0.08, 0.19] | 0.12 [0.11, 0.16] | 0.11 [0.08, 0.12] | 0.11 [0.06, 0.13] | 0.06 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid (22:6 n-3; DHA) | 0.33 [0.24, 0.47] | 0.39 [0.25, 0.43] | 0.88 [0.70, 1.11] | 1.05 [0.82, 1.58] | <0.0001 |

| Triene/Tetraene | 0.016 [0.014, 0.022] | 0.015 [0.010, 0.025] | 0.016 [0.011, 0.023] | 0.015 [0.014, 0.022] | 0.92 |

Highlights.

This is a pilot clinical trial investigating plasma fatty acids and prostaglandin metabolites in pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) who were receiving oral docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation. In a randomized cross-over design, participants were given DHA at two different doses in addition to a placebo with no DHA. At baseline and after each study period, plasma fatty acids and urine prostaglandin-E metabolites (PGE-M) were analyzed.

These pediatric participants were representative of our CF clinical center with a good clinical baseline. However, we observed elevation of urine PGE-M at baseline. PGE-M decreased with DHA supplementation, but a placebo effect was also observed. Plasma DHA levels increased in the blood with DHA supplementation, but there were not clinically meaningful changes in other fatty acids. However, in comparison to previous reports, at baseline we observed higher linoleic acid levels, lower arachidonic acids levels, and a normal triene/tetraene (T/T) ratio.

These fatty acid results suggest that previous observations may no longer be true in a new generation of pediatric CF patients, though further research is needed. In addition, with further investigation urine PGE-M may have utility as a CF biomarker.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This project was supported by T32 GM07569 in clinical pharmacology and the Vanderbilt University CTSA grant UL1 RR024975.

We would like to thank Martek Pharmaceuticals for supplying the DHA supplement and placebo capsules.

We would also like to thank Ginger Milne, Ph.D., and other members of the Vanderbilt Eicosanoid Core Laboratory for their help in running the urine PGE-M samples.

Footnotes

The work was presented as a poster abstract at the 2015 North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dhooghe B, Noel S, Huaux F, Leal T. Lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis: Pathogenesis and novel therapies. Clin Biochem. 2014 May;47(7–8):539–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sagel SD, Chmiel JF, Konstan MW. Sputum biomarkers of inflammation in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007 Aug 1;4(4):406–17. doi: 10.1513/pats.200703-044BR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ordonez CL, Henig NR, Mayer-Hamblett N, Accurso FJ, Burns JL, Chmiel JF, et al. Inflammatory and microbiologic markers in induced sputum after intravenous antibiotics in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 Dec 15;168(12):1471–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200306-731OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiron R, Grumbach YY, Quynh NV, Verriere V, Urbach V. Lipoxin A(4) and interleukin-8 levels in cystic fibrosis sputum after antibiotherapy. J Cyst Fibros. 2008 Nov;7(6):463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freedman SD, Blanco PG, Zaman MM, Shea JC, Ollero M, Hopper IK, et al. Association of cystic fibrosis with abnormalities in fatty acid metabolism. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 5;350(6):560–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batal I, Ericsoussi MB, Cluette-Brown JE, O’Sullivan BP, Freedman SD, Savaille JE, et al. Potential utility of plasma fatty acid analysis in the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Clin Chem. 2007 Jan;53(1):78–84. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freedman SD, Katz MH, Parker EM, Laposata M, Urman MY, Alvarez JG. A membrane lipid imbalance plays a role in the phenotypic expression of cystic fibrosis in cftr(−/−) mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Nov 23;96(24):13995–4000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jabr S, Gartner S, Milne GL, Roca-Ferrer J, Casas J, Moreno A, et al. Quantification of major urinary metabolites of PGE2 and PGD2 in cystic fibrosis: Correlation with disease severity. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2013 Aug;89(2–3):121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caron E, Desseyn JL, Sergent L, Bartke N, Husson MO, Duhamel A, et al. Impact of fish oils on the outcomes of a mouse model of acute Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection. Br J Nutr. 2015 Jan;7:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514003705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leggieri E, De Biase RV, Savi D, Zullo S, Halili I, Quattrucci S. Clinical effects of diet supplementation with DHA in pediatric patients suffering from cystic fibrosis. Minerva Pediatr. 2013 Aug;65(4):389–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Biervliet S, Devos M, Delhaye T, Van Biervliet JP, Robberecht E, Christophe A. Oral DHA supplementation in DeltaF508 homozygous cystic fibrosis patients. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008 Feb;78(2):109–15. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Njoroge SW, Laposata M, Katrangi W, Seegmiller AC. DHA and EPA reverse cystic fibrosis-related FA abnormalities by suppressing FA desaturase expression and activity. J Lipid Res. 2012 Feb;53(2):257–65. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M018101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siguel EN, Chee KM, Gong JX, Schaefer EJ. Criteria for essential fatty acid deficiency in plasma as assessed by capillary column gas-liquid chromatography. Clin Chem. 1987 Oct;33(10):1869–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramsey KA, Schultz A, Stick SM. Biomarkers in Paediatric Cystic Fibrosis Lung Disease. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2015 Sep;16(4):213–8. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders DB, Fink A, Mayer-Hamblett N, Schechter MS, Sawicki GS, Rosenfeld M, et al. Early Life Growth Trajectories in Cystic Fibrosis are Associated with Pulmonary Function at Age 6 Years. J Pediatr. 2015 Sep 2; doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christophe A, Robberecht E, De Baets F, Franckx H. Increase of long chain omega-3 fatty acids in the major serum lipid classes of patients with cystic fibrosis. Ann Nutr Metab. 1992;36(5–6):304–12. doi: 10.1159/000177734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson WR, Jr, Astley SJ, McCready MM, Kushmerick P, Casey S, Becker JW, et al. Oral absorption of omega-3 fatty acids in patients with cystic fibrosis who have pancreatic insufficiency and in healthy control subjects. J Pediatr. 1994 Mar;124(3):400–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jumpsen JA, Brown NE, Thomson AB, Paul Man SF, Goh YK, Ma D, et al. Fatty acids in blood and intestine following docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2006 May;5(2):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurlandsky LE, Bennink MR, Webb PM, Ulrich PJ, Baer LJ. The absorption and effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids on serum leukotriene B4 in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1994 Oct;18(4):211–7. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950180404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd-Still JD, Powers CA, Hoffman DR, Boyd-Trull K, Lester LA, Benisek DC, et al. Bioavailability and safety of a high dose of docosahexaenoic acid triacylglycerol of algal origin in cystic fibrosis patients: a randomized, controlled study. Nutrition. 2006 Jan;22(1):36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maqbool A, Schall JI, Gallagher PR, Zemel BS, Strandvik B, Stallings VA. Relation between dietary fat intake type and serum fatty acid status in children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012 Nov;55(5):605–11. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182618f33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldamiz-Echevarria L, Prieto JA, Andrade F, Elorz J, Sojo A, Lage S, et al. Persistence of essential fatty acid deficiency in cystic fibrosis despite nutritional therapy. Pediatr Res. 2009 Nov;66(5):585–9. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181b4e8d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alicandro G, Faelli N, Gagliardini R, Santini B, Magazzu G, Biffi A, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study on high-dose oral algal docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in children with cystic fibrosis. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2013 Feb;88(2):163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roulet M, Frascarolo P, Rappaz I, Pilet M. Essential fatty acid deficiency in well nourished young cystic fibrosis patients. Eur J Pediatr. 1997 Dec;156(12):952–6. doi: 10.1007/s004310050750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]