Abstract

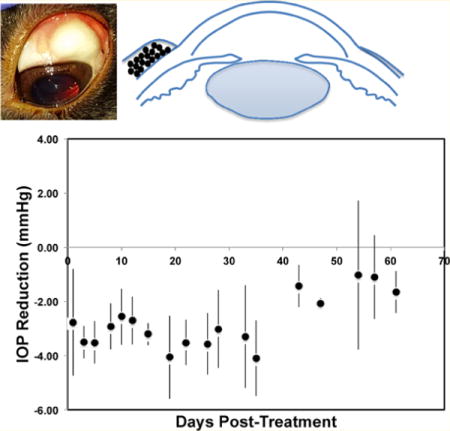

Topical medications that inhibit the enzyme carbonic anhydrase (CAI) are widely used to lower intraocular pressure in glaucoma; however, their clinical efficacy is limited by the requirement for multiple-daily dosing, as well as side effects such as blurred vision and discomfort on drop instillation. We developed a biodegradable polymer microparticle formulation of the CAI dorzolamide that produces sustained lowering of intraocular pressure after subconjunctival injection. Dorzolamide was ion paired with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and sodium oleate (SO) with 0.8% and 1.5% drug loading in poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), respectively. Encapsulating dorzolamide into poly(ethylene glycol)-co-poly(sebacic acid) (PEG3-PSA) microparticles in the presence of triethylamine (TEA) resulted in 14.9% drug loading and drug release that occurred over 12 days in vitro. Subconjunctival injection of dorzolamide-PEG3-PSA microparticles (DPP) in Dutch belted rabbits reduced IOP as much as 4.0 ± 1.5 mmHg compared to untreated fellow eyes for 35 days. IOP reduction after injection of DPP microparticles was significant when compared to baseline untreated IOPs (P < 0.001); however, injection of blank microparticles (PEG3-PSA) did not affect IOP (P = 0.9). Microparticle injection was associated with transient clinical vascularity and inflammatory cell infiltration in conjunctiva on histological examination. Fluorescently labeled PEG3-PSA microparticles were detected for at least 42 days after injection, indicating that in vivo particle degradation is several-fold longer than in vitro degradation. Subconjunctival DPP microparticle delivery is a promising new platform for sustained intraocular pressure lowering in glaucoma.

Keywords: glaucoma, carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, controlled delivery, polymer

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide. Over 60 million people were affected by this vision threatening disease in 2010, and this number is predicted to increase to 112 million by 2040.1–3 To date, lowering of intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only clinically proven therapy to decrease the incidence or progression of glaucoma.4,5 IOP reduction can be accomplished through topical and oral medications, laser treatment, or incisional surgery. Topically applied IOP lowering eye drops are the most commonly used, first-line glaucoma treatment.6

Eye drops lower IOP either by reducing the amount of aqueous humor produced within the eye (carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-adrenergic agonists, and beta-blockers) or by increasing fluid outflow from the eye (alpha-adrenergic agonists and prostaglandin analogues). Daily use of eye drops reduces vision loss due to glaucoma, but its success is hindered by poor patient adherence, preservative and medication toxicity, and limited bioavailability. In the Travatan Dosing Aid Study, nearly half of the patients used their drops less than 75% of the time,7 as judged by an electronic monitoring device. This low adherence was found in spite of patients knowing that they were being monitored and being provided with free medication. The disincentives to ideal eye drop adherence include the fact that they provide no detectable benefit to the patient in terms of symptom relief. In addition, preservatives, such as benzalkonium chloride (BAK), that are used in drop formulation can cause significant eye irritation and redness,8 adding additional reasons for poor drop adherence. Even when patients remember to take their eye drops, there are barriers to proper drop administration. Application of eye drops can test the manual dexterity of an aged population with glaucoma.9 Furthermore, once a drop is applied to the surface of the eye, there are obstacles to its effectiveness, including rapid and extensive loss by tear film dilution and drainage through the nasolacrimal duct. Given such medication clearance and the ocular barriers to drug penetration, it is not surprising that typically <3% of applied medication reaches the target intraocular tissues.10

Controlled delivery of IOP lowering medications for several months after a single administration has the potential to overcome many eye drop limitations. The need for daily drop adherence is eliminated, as is the challenge of drop application. Elimination of the need for preservatives and reduction of peak drug levels could reduce ocular surface toxicity. Clinical followup of glaucoma patients typically occurs 2 to 4 times per year. A controlled release formulation applied by the doctor at appointments every 3 to 6 months would allow IOP control without an increase in visits.

Carbonic anhydrases (CA) are ubiquitous through nature and widely expressed in human tissue, including the gastrointestinal tract, kidney, liver, skeletal muscle, and the eyes. Isoforms II, III, IV, and XII are present in the ciliary processes of the eye,11 where CA II and CA XII are involved in aqueous humor production11 and regulation of IOP. Becker et al. first showed that the systemic CA inhibitor (CAI) acetazolamide reduced IOP by 30%.12 Systemic CAIs are used to treat severe glaucoma; however, side effects are frequently severe and include rare but fatal aplastic anemia. Topical CAI treatment with 2% dorzolamide,13 available since 1995, has no systemic side effects and reduces IOP up to 23% as monotherapy.14 Unfortunately, its use is limited by local eye irritation caused by the low pH and the high viscosity of its formulation.10 In addition, its short duration of action requires 2–3 times daily dosing, decreasing persistence and adherence.15 While a second topical CAI, brinzolamide, reduces IOP up to 18%,16 it also must be administered 2–3 times daily and blurs vision on instillation.17 Development of a controlled release, CAI formulation for local delivery could overcome the limitations of frequent dosing and ocular surface discomfort.

We designed and characterized dorzolamide- and brinzolamide-loaded, polymer microparticles for sustained IOP reduction after subconjunctival injection. Microparticles can be introduced into the subconjunctival space in a minimally invasive manner that may be acceptable18 to patients as a replacement for daily drops. The efficacy and biocompatibility of the microsphere-based preparations were evaluated in vivo in rabbit eyes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Synthesis of PEG3-PSA

Block copolymers of citric acid-[poly(ethylene glycol)]3 and poly(sebacic acid) (PEG3-PSA) were synthesized by melt polycondensation.1,19 Briefly, sebacic acid was refluxed in acetic anhydride to form sebacic acid prepolymer (Acyl-SA). Polyethylene glycol methyl ether (MW 5000, mPEG, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dried under vacuum to constant weight prior to use. Citric-polyethylene glycol (PEG3) was prepared as previously described.20 Methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol)-amine (CH3O-PEG-NH2) MW 5,000 (Rapp Polymer GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) (2.0 g), citric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (25.87 mg), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC, Acros Organic, Geel, Belgium) (82.53 mg), and 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP, Acros Organic, Geel, Belgium) (4.0 mg) were added to 10 mL of methylene chloride (DCM, Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), stirred overnight at room temperature, precipitated, washed with anhydrous ether (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), and dried under vacuum. Acyl-SA and citric-PEG3 (10% w/w) were placed into a flask under nitrogen gas and melted at 180 °C under high vacuum. Nitrogen gas was swept into the flask after 15 min. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min. Polymers were cooled to ambient temperature, dissolved in chloroform, and precipitated into excess petroleum ether. The precipitate was collected by filtration and dried under vacuum to constant weight. Polymer structure was verified by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy in CDCl3 (Bruker Avance 400 MHz FT-NMR, Madison, WI), and FT-IR with potassium bromide pellets on a PerkinElmer 1600 series spectrophotometer (Wellesley, MA). The weight percentage of PEG was estimated by 1H NMR. Molecular weight was monitored by gel permeation chromatography (JASCO AS-1555, Tokyo, Japan) with three columns in series (Waters, Milford, MA; Styragel guard column, 4.6 mm i.d. × 30 mm; HR 3 column, 4.6 mm i.d. × 300 mm; HR 4 column, 4.6 mm i.d. × 300 mm) and polystyrene as standards (Fluka, Milwaukee, WI).

Ion Pair and Microparticle Preparation

Dorzolamide ion pairs were created by dissolving 7.5 mg of dorzolamide in 1 mL of water. The corresponding molar ratio of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) or sodium oleate (SO) was dissolved in another 1 mL of water. The SDS or SO solution was then added in a dropwise manner to the dorzolamide solution. Ion pair compounds were then collected by centrifugation at 4000g, washed with water two times, and lyophilized.

Dorzolamide and brinzolamide microparticles were prepared by dissolving 100 mg of PEG3-PSA or poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA, 50:50, Lakeshore Biomaterials, Birmingham, AL) with either dorzolamide (20 mg, Chempacific, Baltimore, MD) or brinzolamide (20 mg, AvaChem Scientific, San Antonio, TX) in 1 mL of dichloromethane or DMSO respectively. Triethylamine (TEA) was added to the PEG3-PSA mixture, and all mixtures were homogenized (L4RT, Silverson Machines, East Longmeadow, MA) at 6,000 rpm for 1 min into 100 mL of an aqueous solution containing 1% poly(vinyl alcohol) (25 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Particles were hardened by allowing dichloromethane to evaporate at room temperature, while stirring for 2 h. Particles were then collected and washed three times with double distilled water via centrifugation at 6000g for 10 min (International Equipment Co., Needham Heights, MA). Particle size distribution was determined using a Coulter Multisizer IIe (Beckman); briefly about 2 mg of particles were resuspended in 1 mL of double distilled water and added dropwise to 100 mL of ISOTON II solution until the coincidence of the particles was between 8% and 10%. At least 100,000 particles were sized to determine the mean and standard deviation of particle size.

Drug Release from Particles

Particles were suspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 5 mg/mL and incubated at 37 °C on a rotating platform (140 rpm). At selected time points, supernatant was collected by centrifugation (8000g for 5 min) and particles were resuspended in fresh PBS. Drug content in the supernatant was measured by spectrophotometer by measurement of peak intensity at 250 nm and comparison to a standard curve.

Tonometer Calibration

The tonometer (TonoVet; iCare, Vantaa, Finland) used in this study was calibrated for use in dogs, cats, and horses. It was therefore recalibrated for the rabbit eye. Three ex vivo rabbit eyes were cannulated by a 25-gauge needle 3 mm posterior to the limbus. The needle was connected to a manometer (DigiMano1000, Netech, Farmingdale, NY) and reservoir containing balanced salt solution (BSS). The pressure set by reservoir height was verified with the manometer connected to the system and compared to the TonoVet tonometer reading. Final measurements were made after confirming stable IOP for 5 min. Measurements were made for manometer readings between 4 and 24 mmHg. The calibration curve for the ex vivo eyes was y = 1.097x + 1.74 (R2 = 0.98), where x = IOP reported by the TonoVet tonometer and y = manometer reading. Reported IOPs are the corrected values. For IOP measurements in this study, no anesthesia of the animal or the eye was needed, as the instrument is well-tolerated without anesthesia.

Animals

Dutch-belted rabbits of either sex at least 20 weeks of age were used in experimental protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Review Board of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Rabbits were handled in a manner consistent with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animal (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals).

Delivery of Microparticles and Eye Drops

Prior to subconjunctival injection of microparticles, anesthesia was achieved using subcutaneous injection of a mixture of ketamine (25 mg/kg) and xylazine (2.5 mg/kg). An eye drop of 1% proparacaine was followed by 5% betadine eye drop to the operative eye. Then, 0.1 mL of either DPP microparticles (n = 7) or blank microparticles (n = 4) suspended (330 mg/mL) in saline with 0.25% sodium hylaluronate (HA, HA2M-5, Lifecore, Chaska, MN) was administered into the subconjunctival space of the superior temporal region of each eye using a 27 gauge needle. Topical antibiotic ointment was administered to the eye after injection, and the rabbit was examined daily for 7 days to check for signs of infection, inflammation, or irritation. For the repeat injection of DPP particles, animals that had initially undergone injection of DPP particles were followed for 60 days prior to repeat, subconjunctival injection of DPP particles (n = 3).

For the topical delivery group, a single dorzolamide eye drop (2.0% dorzolamide HCL, HiTech Pharmacal Co., Amityville, NY) was administered at 9:00 a.m. unilaterally to the upper conjunctival sac without anesthesia (n = 5).

Clinical Evaluation

IOP was measured with the TonoVet tonometer in awake, restrained rabbits. The TonoVet was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the magnetic probe in a horizontal position. All measurements occurred between 10 a.m. and 12 p.m., were performed by the same technician, and took place in the rabbit housing room. Prior to measurements, each rabbit was restrained for at least 3 min. Three measurements were taken of each eye, and topical anesthesia was not used prior to IOP measurement. If there was more than 2 mmHg of variation between measurements of an individual eye, the rabbit was allowed to acclimate for 3 more minutes before repeat measurement. Prior to microparticle injection or drop administration, each rabbit was acclimatized to the IOP measurement procedure for at least 7 days. Baseline IOP difference between right and left eyes of rabbits was averaged over three measurements taken after the acclimatization process. Anterior segment photographs of the operated eyes were performed of the area of injection, which initially appeared as an elevated zone 4 mm in diameter on the eye surface, referred to here as a bleb. A Moorfields Bleb Grading System,21 designed to quantify the appearance of blebs produced by human glaucoma surgery, was used to assess bleb size, height, and vascularity in all eyes (Table 2). Three masked, trained graders were used to grade photographs using this system.

Table 2.

Description of Conjunctival Grading Scalea

| grade | Area | height | vascularity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | absent | absent | avascular |

| 2 | <25% upper conjunctiva | small elevation | normal |

| 3 | 25–50% upper conjunctiva | moderate elevation | mild |

| 4 | 50–75% upper conjunctiva | large elevation | moderate |

| 5 | 75–100% | severe |

Conjunctival morphology was graded using the Moorfields Bleb Grading System.

Histology

Animals were sacrificed with an intravenous overdose of Beuthanasia-D (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ). Following enucleation, eyes were exposed to a sucrose gradient and frozen in optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and serially cut into sections of 10 μm thickness. Sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E).

Particle Retention Study

The erosion of microparticles after subconjunctival administration was investigated by imaging fluorescently labeled particles1 on the eye with the Xenogen IVIS spectrum optical imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences Inc., Hopkinton, MA). Rabbits were anesthetized as described above, and PEG3-PSA-doxorubicin (DOX) particles (33 mg in 100 μL of saline with 0.25% HA) were injected subconjunctivally into the superotemporal quadrant using a 27-gauge needle. Development of PEG3-PSA-DOX was described previously;1 these particles contain the same polymer as DPP microparticles. Additionally, they have fluorescence due to the presence of DOX. Total fluorescence at the injection site was recorded at 500/600 nm, and images were analyzed using Living Image 3.0 software (Caliper Lifesciences, Inc.). Retention of particles was quantified by comparing the fluorescence counts immediately after injection to the values obtained over time.

Statistical Analysis

All values are mean ± standard deviation (SD). IOP reduction was calculated as the difference between the treated and untreated fellow eyes. IOP reduction following treatment was compared to mean intereye IOP difference (±SD) established on measurement of baseline, pretreatment IOPs. One-way analysis of variance test (ANOVA) was used for means. Dunnett’s test (α = 0.05) was performed to determine statistical significance for individual time points. Area under the curve (AUC) as calculated using the trapezoid rule and statistical significance was calculated using paired t test. P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Preparation and Characterization of Microparticles

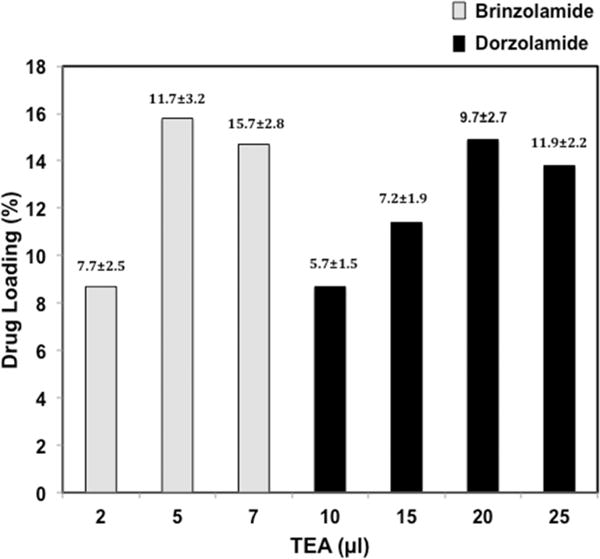

Dorzolamide and brinzolamide are hydrophilic compounds that were resistant to encapsulation into PLGA, with loading of 0.5% (10.9 ± 5.3 μm in diameter) and 1.8% (9.7 ± 2.7 μm in diameter) by weight on initial attempts, respectively (Table 1). Ion pairing of hydrophilic drugs with hydrophobic compounds can improve compound–polymer compatibility and drug loading.22,23 Increased drug loading of dorzolamide was seen with ion pairing, but it was not substantial. Ion pairing dorzolamide with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) improved loading only to 0.8% (15.9 ± 10.1 μm in diameter), and ion pairing with sodium oleate (SO) improved loading to 1.5% (28.1 ± 10.2 μm in diameter). We next attempted to encapsulate the CAIs in a more hydrophilic polymer. PEG3-PSA polymer was synthesized with PEG contents of 9.9% or 1.9% and a weight-average molecular weight of 22.8 ± 1.4 kDa with a polydispersity index of 1.83 ± 0.24. Dorzolamide was encapsulated in PEG3-PSA polymer at a higher level (3.9%) than in PLGA; however, the highest drug loading was obtained when the free base forms of dorzolamide (14.9%, 9.7 ± 2.7 μm in diameter) and brinzolamide (15.8%, 11.7 ± 3.2 μm in diameter) were encapsulated in PEG3-PSA (Figure 1). The physiochemical properties of the dorzolamide and brinzolamide microparticles are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Physiochemical Properties of Microparticlesa

| drug | formulation | ion pair (molar ratio) | diameter (μm) | drug loading (wt %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dorzolamide | PLGA | 10.9 ± 5.3 | 0.5 | |

| SDS (0.5) | 13.3 ± 6.7 | 0.4 | ||

| SDS (1) | 15.9 ± 10.1 | 0.8 | ||

| SDS (1.5) | 13.1 ± 8.6 | 0.4 | ||

| SDS (2) | 11.5 ± 8.1 | 0.4 | ||

| SO (0.5) | 10.6 ± 4.5 | 1.3 | ||

| SO (1) | 21.6 ± 8.5 | 1.4 | ||

| SO (1.5) | 28.1 ± 10.2 | 1.5 | ||

| SO (2) | 27.9 ± 10.2 | 1.2 | ||

| PEG3-PSA | 3.9 | |||

| PEG3-PSA (TEA) | 9.7 ± 2.7 | 14.9 | ||

| brinzolamide | PLGA | 10.9 ± 6.2 | 1.8 | |

| PEG3-PSA (TEA) | 11.7 ± 3.2 | 15.8 |

CAI encapsulation was attempted using PLGA and PEG3-PSA polymer. Ion pairing with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and SO (sodium oleate) improved loading efficiency several-fold, however, optimal loading was obtained with PEG3-PSA polymer in the presence of TEA.

Figure 1.

Brinzolamide and dorzolamide loading is affected by triethylamine (TEA) addition. Particle size (μm ± SD) is shown on top of each column. 100 mg of PEG3-PSA polymer was used with 20 mg of either dorzolamide or brinzolamide.

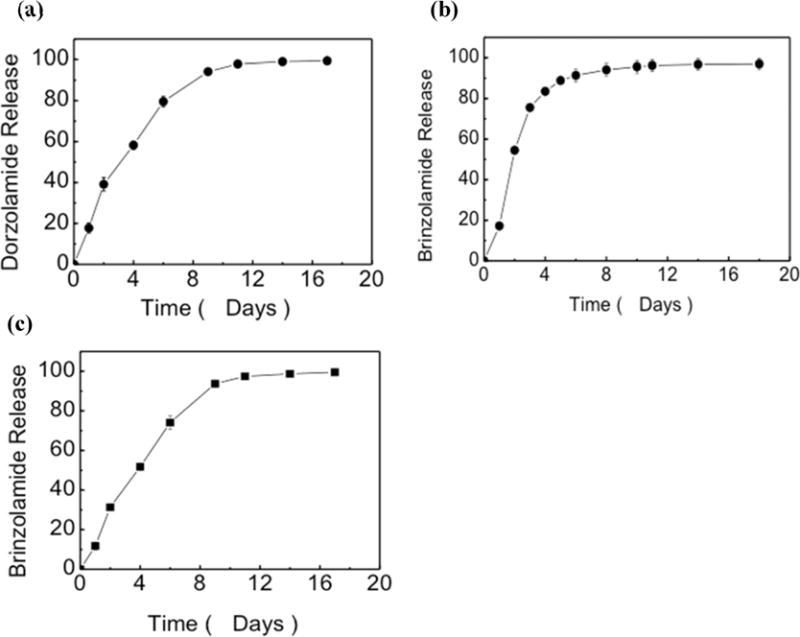

In Vitro Drug Release

In vitro release of dorzolamide and brinzolamide from PEG3-PSA occurred over 12 and 8 days respectively under infinite sink conditions (Figure 2). Release over the initial 24 h was 18% for each drug although drug release over 96 h occurred more quickly from brinzolamide-loaded particles than DPP. Decreasing the PEG content of PEG3-PSA from 10% to 2% (by weight) extended the duration of release of brinzolamide (Figure 2c) but not dorzolamide. Dorzolamide microparticles with 10% PEG were used for in vivo experiments in order to maximize the PEG content and duration of drug release.

Figure 2.

In vitro release kinetics of dorzolamide and brinzolamide from PEG3-PSA microparticles. PEG3-PSA dorzolamide and brinzolamide microparticles using 10% PEG release drug (shown in % of total) over 12 and 8 days respectively (a and b). Release of brinzolamide was extended to 12 days when the PEG content was decreased to 2% (c).

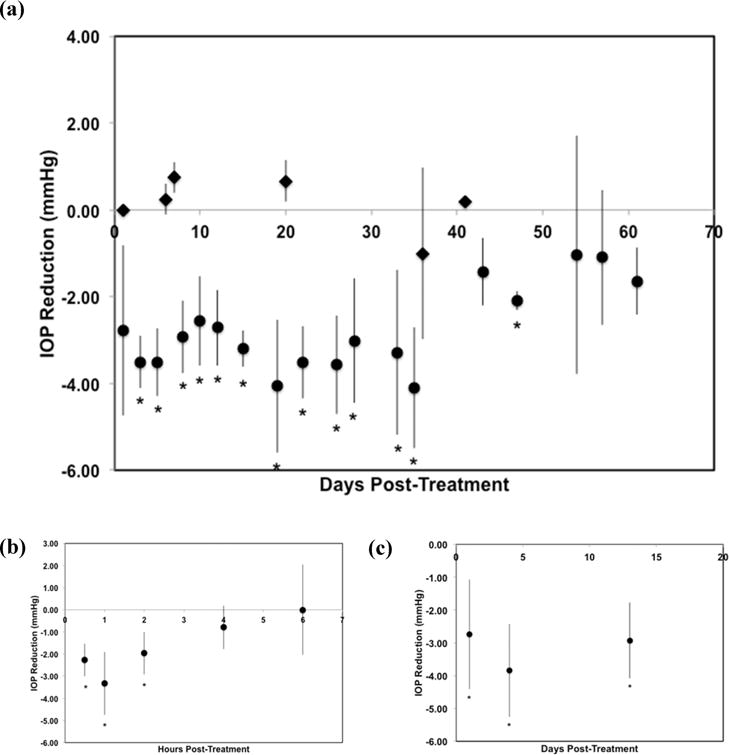

IOP Lowering in Normotensive Rabbits

We evaluated the efficacy of subconjunctivally delivered DPP in normotensive, pigmented rabbits. While IOP lowering would potentially be more dramatic in eyes that have higher than normal IOP, there is no consistent method for elevating IOP in rabbits for sustained periods of time that would leave the eye in a relatively normal physiological state. Topically delivered, 2% dorzolamide eye drops reduce IOP in normotensive rabbits only transiently,24 and we confirmed that IOP reduction after administration of 2% dorzolamide eye drops lasted for <6 h and led to a modest, but significant, reduction in IOP compared to the untreated eye (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.01) (Figure 3). A crossover effect of IOP lowering in the untreated eye caused by systemic drug absorption was not anticipated with the use of topical dorzolamide and was not observed (Supplemental Figure 1). Indeed the IOP in the untreated eye was unaffected by dorzolamide treatment. Subconjunctival injection of blank microparticles without dorzolamide (PEG3-PSA) did not lower IOP over the course of particle degradation (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.9) (Figure 3). In contrast, subconjunctival injection of DPP reduced IOP as much as 4.06 ± 1.53 mmHg when compared to untreated fellow eyes (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001), and IOP reduction continued for 35 days after particle injection (Dunnett’s test, P = 0.02) (Figure 3). We determined AUC for DPP and blank microparticles; there was a significant difference with DPP (−113.4 ± 18.7 mmHg·days) and blank control microparticles (18.4 ± 18.2 mmHg·days) (P = 0.001). Repeat, subconjunctival injection of dorzolamide microparticles (0.1 mL, 330 mg/mL) was performed in previously injected eyes at 60 days after initial injection, and IOP was followed for 13 days (Figure 3c). IOP reduction occurred to a similar extent as after the initial injection; however, IOP was not followed until normalization. IOP measurements of control and treated eyes are included in Supplemental Figure 1.

Figure 3.

IOP reduction after subconjunctival injection of DPP. Subconjunctival injection of DPP (a, circles) reduced IOP for 35 days (n = 7) while blank microparticles without dorzolamide (PEG3-PSA) did not reduce IOP (a, diamonds) (n = 4). Topical application of 2% dorzolamide drops reduced IOP for several hours (b) (n = 5). Repeat injection of DPP 60 days after initial injection (c) reduced IOP (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

In Vivo Biosafety

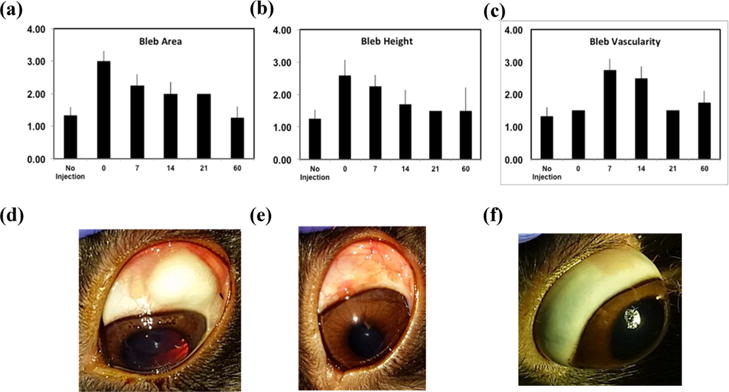

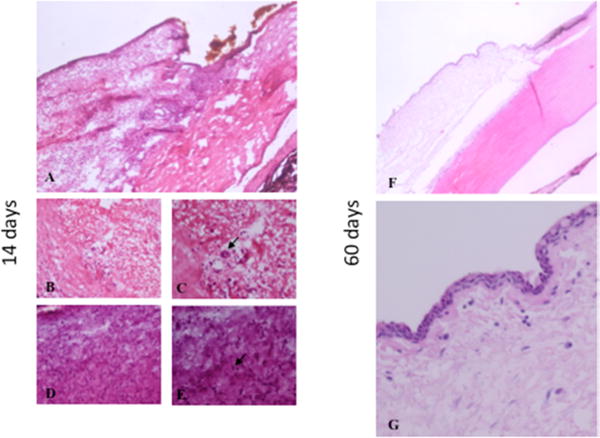

Rabbits showed no clinical signs of discomfort after subconjunctival injection of microparticles. The injected material formed an elevation (bleb) in the conjunctiva that slowly flattened over 3 weeks. The conjunctival vascularity over the bleb was mild, peaked at 7–14 days, and was absent 21 days after injection (Figure 4). Histologic sections taken 14 days after particle injection demonstrated that the polymer was localized in the subconjunctival connective tissue with associated lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells, demonstrating a foreign body tissue response to DPP. Histologic findings consistent with inflammation and fibrosis were absent 60 days after DPP injection (Figure 5). There was no clinical evidence of cataract formation, aqueous humor inflammation, or abnormality in the retina, choroid, and sclera. Rabbits did not demonstrate signs of ocular discomfort at any point after particle injection.

Figure 4.

Bleb appearance and grading after microparticle injection. Bleb area (a), bleb height (b), and bleb vascularity (c) were monitored postinjection and graded using a modified version of the Moorfields Bleb Grading System (n = 4). Eye appearance immediately following particle injection (d), 14 days after injection (e), and 60 days after injection (f).

Figure 5.

Bleb histology after microparticle injection. Two weeks after injection (A, B, C, D, E). Particles are located in the subconjunctival space (A) with lymphocyte infiltration (B, C) and polynuclear giant cells (arrow). A fibrotic response was observed in one eye with infiltration of fibroblasts (D, E, arrow). Sixty days after injection, inflammatory and fibrotic cells were no longer present (F, G).

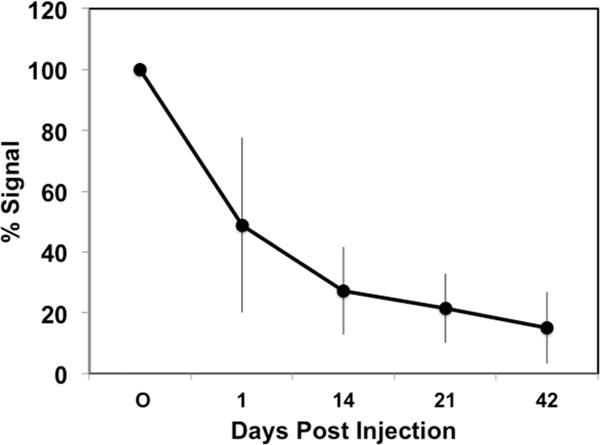

In Vivo Polymer Retention

Since the duration of in vivo IOP lowering was significantly longer than that of in vitro drug release, it was likely that particle erosion occurred more slowly in vivo. To corroborate this supposition, we quantified the persistence of PEG3-PSA-Dox particles, which are similar to DPP in degradation kinetics,1 with longitudinal, in vivo whole eye imaging. After subconjunctival injection, PEG3-PSA-Dox particle fluorescence was substantial for over one month and declined to <10% of initial fluorescence by 43 days (Figure 6). Thus, PEG3-PSA particle fluorescence was similar in time course to the IOP lowering effect seen with dorzolamide microparticles. Interestingly, about 50% of the fluorescent signal declined over the first 24 h after particle injection. No particle leakage was seen at the time of injection; however, particle loss cannot be excluded as a cause of this decrease in fluorescence.

Figure 6.

Particle degradation after subconjunctival injection. Total fluorescence was followed in vivo after subconjunctival injection of PEG3-PSA-Dox microparticles (n = 4).

DISCUSSION

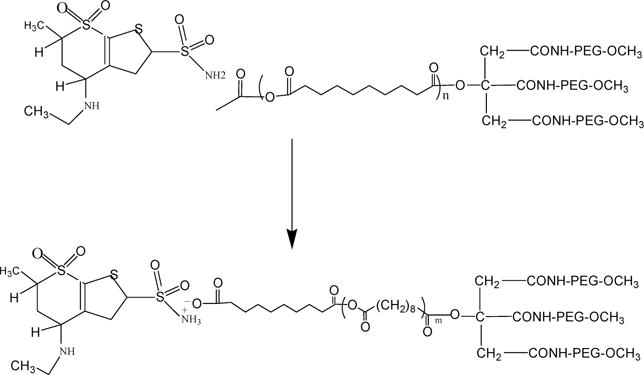

We developed a biodegradable microparticle platform with high drug loading and controlled release of the CAI dorzolamide that effectively lowered IOP in rabbits for over one month. Initial attempts to encapsulate dorzolamide into PLGA microparticles yielded insufficient drug loading (0.5%) that was modestly improved by ion pairing dorzolamide with SDS (0.8%) and SO (1.5%). Improved loading of dorzolamide and brinzolamide to 14.9% and 15.8% respectively was obtained when CAI free bases were combined with a polyanhydride polymer (PEG3-PSA). We propose that this improved encapsulation of dorzolamide, when combined with a polyanhydride polymer and TEA, likely occurred through formation of a complex of the free base of the CAI with polyanhydride (Figure 7). While drug release from these particles was completed in 12 days in vitro, IOP reduction was observed for at least 35 days in vivo after subconjunctival injection in normotensive rabbits. The degree of IOP reduction compared to untreated control eyes varied from 2 to 4 mmHg and is in a range considered clinically significant in glaucoma treatment.

Figure 7.

Proposed structure of the free base of dorzolamide (left) complexed to PEG3-PSA (right).

Topical CAIs require multiple daily doses and can cause irritation and blurriness on instillation. Alternate formulations were developed previously to overcome these limitations. Topical formulations utilizing hydrogels, micelles, nanocrystals, biodegradable nanoparticles, and dendrimers decrease the number of daily drops that need to be given.25–30 While transitioning topical CAIs from drops that must be given two or three times a day to a drop that only needs to be given once a day could positively impact patient adherence, it does not eliminate the issue of poor patient adherence.31 Biodegradable implants are able to extend CAI release for several months. In vitro release of dorzolamide for over 90 days was accomplished using a polycaprolactone (PCL) blending implant. Using this implant, in vivo IOP lowering for at least 60 days was obtained in ocular hypertensive rabbits.32 An implant created from photo-cross-linked poly(propylene fumarate) (PPF)/poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP) matrix released the CAI acetazolamide over a period of approximately 200 days.33 Implant placement, however, requires that incisions are made in the conjunctiva and CAI releasing implants were associated with inflammation and fibrosis. Here we describe an additional formulation for controlled release of CAIs that allows sustained IOP lowering after minimal conjunctival manipulation on particle injection.

Subconjunctival injection is a promising method for delivery of controlled release medications. The subconjunctiva is a potential space that underlies the epithelial and connective tissue layers covering the sclera. Medication can be injected into this space without penetrating the structural components of the eye, thus avoiding the risks associated with intraocular injection, such as temporary blurred vision, infection, retinal detachment, and vitreous hemorrhage.34 Furthermore, subconjunctival delivery could favor drug penetration to the intraocular target tissues of interest, since it places the drug close to the external sclera. Transscleral rather than transcorneal drug penetration was shown to be a route of CAI delivery to the ciliary body, its site of action in lowering IOP.35 Subconjunctival delivery of ocular treatments has been utilized for decades, including triamcinolone acetonide and other steroids for inflammatory disease,36 antibiotic injections for infectious disease, and antiproliferative drugs to augment glaucoma surgery.37

Subconjunctival delivery of formulations for sustained IOP lowering has shown promise in animal studies and preliminary human trials. Latanoprost-loaded liposomes achieved sustained IOP reduction after subconjunctival injection in normotensive rabbits and hypertensive monkeys and in preliminary human trials.38,39 Subconjunctival injection of controlled release formulations of brimonidine and timolol lowered IOP for 28 days and >4 months, respectively.40,41 The addition of a formulation for controlled release of a CAI after subconjunctival injection adds another glaucoma treatment option. It is likely that multiple, controlled release treatment options will be needed to adequately meet clinical needs of glaucoma treatment. More than one medication is often required to achieve sufficient IOP reduction for clinical efficacy. In the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Trial (OHTS), 39% of patients required more than one IOP lowering medication to achieve a 20% reduction from baseline IOP.5 In the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study (CIGTS), more than 75% of patients needed 2 or more medications to achieve adequate IOP lowering.42 In addition, responses to individual treatments can vary between patients. After 6 months of treatment with either latanoprost or timolol, 17% and 38% of patients were classified as drug nonresponders (less than 20% IOP reduction from baseline), respectively.43 Taken together, these studies highlight the need for multiple treatment options for sustained IOP reduction in glaucoma treatment.

Duration of IOP lowering in vivo following DPP injection was significantly greater than predicted by its in vitro release kinetics. IOP lowering following subconjunctival injection of DPP was observed for 35 days in vivo although in vitro release was limited to 12 days. Increased duration of drug effect in vivo over in vitro release duration has been previously shown. For example, intravitreally injected doxorubicin conjugated microparticles showed in vivo inhibition of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) for 5 weeks despite in vitro drug release that was complete after 1 week.1 Longer in vivo IOP lowering was also demonstrated after subconjunctival placement of controlled release formulations of latanoprost and timolol.38,40 There are several possible reasons for longer in vivo action compared to in vitro release, including the following: injected particles may exhibit increased residence time in vivo compared to in vitro, there may be delayed clearance of free drug, and the IOP lowering effect may persist after drug clearance. For example, topical latanoprost treatment reduces scleral collagen and increases matrix metalloproteinase levels.44 These changes in scleral structure could lead to continued IOP reduction after drug washout. No such effect was documented after CAI treatment. Increased residence time of particles, however, was seen after subconjunctival injection of PEG3-PSA particles. Fluorescently labeled PEG3-PSA particles were detected as much as 6 weeks after subconjunctival injection.

Particle residence of PEG3-PSA-Dox was approximately 1 week longer in duration than the IOP lowering effects of DPP particles. Several factors likely explain this difference. Dorzolamide is a more hydrophilic compound than doxorubicin, therefore drug release from DPP could occur more rapidly in vivo than from PEG3-PSA-Dox particles. The IOP lowering effects of the DPP particles could be lost prior to complete degradation. Near complete inhibition of carbonic anhydrase is needed for IOP reduction by CAIs.45 It is likely that as the particles near complete degradation, this threshold of enzymatic inhibition is passed and IOP reduction does not occur. If used clinically it would therefore be necessary to repeat particle injection prior to the complete degradation of the prior injection in order to maintain a reduced IOP.

The present experiments have some recognized limitations. The length of IOP lowering would be more ideally 3–6 months rather than the present demonstration of a 34 day effect. The present duration of IOP lowering is not clinically viable and needs to be extended prior to considering clinical use. We are conducting further modifications of the PEG3-PSA polymer to achieve this longer duration including incorporation of 1,3-bis(p-carboxyphenoxy)propane into the polymer, which was shown to increase the time of polymer degradation.46 In addition, long-term studies comparing DPP with 2% dorzolamide drop administration will create a better reference for the IOP lowering efficacy of DPP. While it would be expected that the absolute IOP lowering would be even greater if an animal model of glaucoma were used, there are no such useful models in rabbits that preserve the relatively normal physiology of the eye. We have begun tests of this platform with additional drugs in a rat model of experimental IOP elevation. Additionally, eye redness and histologic inflammation occurred transiently after particle injection. Particle formulation could be optimized further to minimize associated inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by PHS Research Grants EY 01765 (Core Facility Grant, Wilmer Institute), EY02120, K08EY024952, a Wilmer-KKESH collaborative research grant, and the generous support of Mary Bartkus.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00343.

IOP after subconjunctival injection of DPP (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Iwase T, Fu J, Yoshida T, Muramatsu D, Miki A, Hashida N, Lu L, Oveson B, Lima e Silva R, Seidel C, Yang M, Connelly S, Shen J, Han B, Wu M, Semenza GL, Hanes J, Campochiaro PA. Sustained Delivery of a HIF-1 Antagonist for Ocular Neovascularization. J Controlled Release. 2013;172(3):625–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The Number of People with Glaucoma Worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tham Y-C, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng C-Y. Global Prevalence of Glaucoma and Projections of Glaucoma Burden Through 2040: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M, Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group Reduction of Intraocular Pressure and Glaucoma Progression: Results From the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(10):1268–1279. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.10.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, Parrish RK, Wilson MR, Gordon MO. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a Randomized Trial Determines That Topical Ocular Hypotensive Medication Delays or Prevents the Onset of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. discussion 829–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman DS, Nordstrom B, Mozaffari E, Quigley HA. Glaucoma Management Among Individuals Enrolled in a Single Comprehensive Insurance Plan. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(9):1500–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okeke CO, Quigley HA, Jampel HD, Ying G-S, Plyler RJ, Jiang Y, Friedman DS. Adherence with Topical Glaucoma Medication Monitored Electronically the Travatan Dosing Aid Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(2):191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver LH. Ocular Comfort of Brinzolamide 1.0% Ophthalmic Suspension Compared with Dorzolamide 2.0% Ophthalmic Solution: Results From Two Multicenter Comfort Studies. Brinzolamide Comfort Study Group. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44(Suppl. 2):S141–S145. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(99)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai T, Robin AL, Smith JP. An Evaluation of How Glaucoma Patients Use Topical Medications: a Pilot Study. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2007;105:29–33. discussion 33–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Banditt P. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Dorzolamide. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(3):197–205. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Supuran CT. Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20(12):3467–3474. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becker B. The Mechanism of the Fall in Intraocular Pressure Induced by the Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor, Diamox. Am J Ophthalmol. 1955;39(2 Part 2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(55)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maren TH, Jankowska L, Sanyal G, Edelhauser HF. The Transcorneal Permeability of Sulfonamide Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors and Their Effect on Aqueous Humor Secretion. Exp Eye Res. 1983;36(4):457–479. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(83)90041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strahlman E, Tipping R, Vogel R. A Double-Masked, Randomized 1-Year Study Comparing Dorzolamide (Trusopt), Timolol, and Betaxolol. International Dorzolamide Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113(8):1009–1016. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100080061030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and Persistence with Glaucoma Therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(6, Suppl. 1):S57–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silver LH. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Brinzolamide (Azopt), a New Topical Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Brinzolamide Primary Therapy Study Group. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126(3):400–408. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00095-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iester M. Brinzolamide Ophthalmic Suspension: a Review of Its Pharmacology and Use in the Treatment of Open Angle Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(3):517–523. doi: 10.2147/opth.s3182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foo RCM, Lamoureux EL, Wong RCK, Ho S-W, Chiang PPC, Rees G, Aung T, Wong TT. Acceptance, Attitudes, and Beliefs of Singaporean Chinese Toward an Ocular Implant for Glaucoma Drug Delivery. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 2012;53(13):8240–8245. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu J, Fiegel J, Krauland E, Hanes J. New Polymeric Carriers for Controlled Drug Delivery Following Inhalation or Injection. Biomaterials. 2002;23(22):4425–4433. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Shabat S, Kumar N, Domb AJ. PEG-PLA Block Copolymer as Potential Drug Carrier: Preparation and Characterization. Macromol Biosci. 2006;6(12):1019–1025. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200600165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells AP, Ashraff NN, Hall RC, Purdie G. Comparison of Two Clinical Bleb Grading Systems. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer JD, Manning MC. Hydrophobic Ion Pairing: Altering the Solubility Properties of Biomolecules. Pharm Res. 1998;15(2):188–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1011998014474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higashiyama M, Inada K, Ohtori A, Tojo K. Improvement of the Ocular Bioavailability of Timolol by Sorbic Acid. Int J Pharm. 2004;272(1–2):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sugrue MF. The Preclinical Pharmacology of Dorzolamide Hydrochloride, a Topical Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1996;12(3):363–376. doi: 10.1089/jop.1996.12.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra V, Jain NK. Acetazolamide Encapsulated Dendritic Nano-Architectures for Effective Glaucoma Management in Rabbits. Int J Pharm. 2014;461(1–2):380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2013.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katiyar S, Pandit J, Mondal RS, Mishra AK, Chuttani K, Aqil M, Ali A, Sultana Y. In Situ Gelling Dorzolamide Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Glaucoma. Carbohydr Polym. 2014;102:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Liu H, Liu L-L, Cai C-N, Xin H-X, Liu W. Design and Evaluation of a Brinzolamide Drug-Resin in Situ Thermosensitive Gelling System for Sustained Ophthalmic Drug Delivery. Chem Pharm Bull. 2014;62(10):1000–1008. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c14-00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribeiro A, Veiga F, Santos D, Torres-Labandeira JJ, Concheiro A, Alvarez-Lorenzo C. Bioinspired Imprinted PHEMA-Hydrogels for Ocular Delivery of Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitor Drugs. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(3):701–709. doi: 10.1021/bm101562v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro A, Sosnik A, Chiappetta DA, Veiga F, Concheiro A, Alvarez-Lorenzo C. Single and Mixed Poloxamine Micelles as Nanocarriers for Solubilization and Sustained Release of Ethoxzolamide for Topical Glaucoma Therapy. J R Soc, Interface. 2012;9(74):2059–2069. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu W, Li J, Wu L, Wang B, Wang Z, Xu Q, Xin H. Ophthalmic Delivery of Brinzolamide by Liquid Crystalline Nanoparticles: in Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2013;14(3):1063–1071. doi: 10.1208/s12249-013-9997-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hermann MM, Papaconstantinou D, Muether PS, Georgopoulos G, Diestelhorst M. Adherence with Brimonidine in Patients with Glaucoma Aware and Not Aware of Electronic Monitoring. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(4):e300–e305. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Natu MV, Gaspar MN, Fontes Ribeiro CA, Cabrita AM, de Sousa HC, Gil MH. In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation of an Intraocular Implant for Glaucoma Treatment. Int J Pharm. 2011;415(1–2):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hacker MC, Haesslein A, Ueda H, Foster WJ, Garcia CA, Ammon DM, Borazjani RN, Kunzler JF, Salamone JC, Mikos AG. Biodegradable Fumarate-Based Drug-Delivery Systems for Ophthalmic Applications. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2009;88A(4):976–989. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falavarjani KG, Nguyen QD. Adverse Events and Complications Associated with Intravitreal Injection of Anti-VEGF Agents: a Review of Literature. Eye (London, U K) 2013;27(7):787–794. doi: 10.1038/eye.2013.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schoenwald RD, Deshpande GS, Rethwisch DG, Barfknecht CF. Penetration Into the Anterior Chamber via the Conjunctival/Scleral Pathway. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1997;13(1):41–59. doi: 10.1089/jop.1997.13.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Athanasiadis Y, Tsatsos M, Sharma A, Hossain P. Subconjunctival Triamcinolone Acetonide in the Management of Ocular Inflammatory Disease. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2013;29(6):516–522. doi: 10.1089/jop.2012.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Buskirk EM. Five-Year Follow-Up of the Fluorouracil Filtering Surgery Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122(5):751–752. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Natarajan JV, Chattopadhyay S, Ang M, Darwitan A, Foo S, Zhen M, Koo M, Wong TT, Venkatraman SS. Sustained Release of an Anti-Glaucoma Drug: Demonstration of Efficacy of a Liposomal Formulation in the Rabbit Eye. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24513. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Natarajan JV, Darwitan A, Barathi VA, Ang M, Htoon HM, Boey F, Tam KC, Wong TT, Venkatraman SS. Sustained Drug Release in Nanomedicine: a Long-Acting Nanocarrier-Based Formulation for Glaucoma. ACS Nano. 2014;8(1):419–429. doi: 10.1021/nn4046024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng XW, Liu KL, Veluchamy AB, Lwin NC, Wong TT, Venkatraman SS. A Biodegradable Ocular Implant for Long-Term Suppression of Intraocular Pressure. Drug Delivery Transl Res. 2015;5(5):469–479. doi: 10.1007/s13346-015-0240-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fedorchak MV, Conner IP, Medina CA, Wingard JB, Schuman JS, Little SR. 28-Day Intraocular Pressure Reduction with a Single Dose of Brimonidine Tartrate-Loaded Microspheres. Exp Eye Res. 2014;125:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE, Janz NK, Wren PA, Mills RP, CIGTS Study Group Interim Clinical Outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study Comparing Initial Treatment Randomized to Medications or Surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(11):1943–1953. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00873-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedman K, Alm A, Gross RL. Pooled-Data Analysis of Three Randomized, Double-Masked, Six-Month Studies Comparing Intraocular Pressure-Reducing Effects of Latanoprost and Timolol in Patients with Ocular Hypertension. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(6):463–465. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200312000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinreb RN. Enhancement of Scleral Macromolecular Permeability with Prostaglandins. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2001;99:319–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maren TH. The Relation Between Enzyme Inhibition and Physiological Response in the Carbonic Anhydrase System. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1963;139:140–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanes J, Fu J, Fiegel J. Biodegradable Polymer Compositions, Compositions and Uses Related. US 7163697. US Patent. 2007;B2

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.