Abstract

The photochemical reaction of Fe2(S2)(CO)6 and Ph2CS affords the perthiolate Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6 (1) in good yield. As confirmed crystallographically, 1 contains a previously elusive perthiolate ligand. The related reaction of Fe2(S2)(CO)5-(PPh3) and Ph2CS gave Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)5(PPh3). Although Fe3S2(CO)9 and Ph2CS failed to efficiently give Fe2(S2CPh2)(CO)6, this compound could be prepared by desulfurization of 1 using PPh3.

Keywords: Iron sulfides, Thiones, Photochemistry, Perthiolates, Desulfurization

Graphical Abstract

The photoaddition of Ph2CS to Fe2(S2)(CO)6 gives the rare diiron perthiolate Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6. Desulfurization of the perthiolate gives Fe2(S2CPh2)(CO)6. These simple reactions provide access to Fe-S-CO compounds that previously were difficult to prepare.

Introduction

The chemistry of carbonyl(dithiolato)diiron compounds is rich, consisting of both routine and esoteric complexes. Hundreds of compounds are known with the formula Fe2(SR)2(CO)6, and thousands of CO-substituted derivatives of such compounds have been reported. Foundational compounds include Fe2(SR)2(CO)6 with R = Me, Et, Ph, as well as the more recently popularized pdt and adt derivatives.[1] These complexes have attracted intense attention because of their similarity to the active site of the [FeFe]-hydrogenases, with the hope that synthetic analogues of the enzyme might underpin technologies for producing hydrogen.[2]

Although the complexes Fe2(SR)2(CO)6 can be produced in excellent yields for many R groups, a handful of related complexes have only been obtained in trace amounts. Some of these “esoteric” compounds are quite simple in composition and could in fact be useful building blocks if they were more readily prepared. Examples of such esoteric but fundamental complexes are shown in Scheme 1; they include CS4Fe4(CO)12, C2S4Fe4(CO)12, CH2S2Fe2(CO)6, and CH2S3Fe2(CO)6. The first two are obtained in low (1–2 %) or unspecified yields upon reaction of Fe3(CO)12 with CS2.[3] The third complex in Scheme 1, Fe2(S3CH2)(CO)6, is a derivative of the thiol-perthiol H2C(SH)(S2H), which is unknown and is expected to be labile. The complex was obtained in low yield from the reaction of Fe3(CO)12, S8, and styrene.[4] It is difficult to envision how this combination of reagents produces the observed perthiolate. This complex is formally an adduct of thioformaldehyde and Fe2(S2)(CO)6. Since free CH2S is only stable as a dilute gas, it is not a reasonable reagent.[5] Only the methanedithiolate can be prepared efficiently, by the reaction of Fe3(CO)12 and methanedithiol.[6]

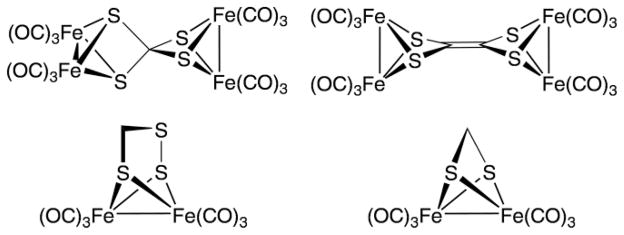

Scheme 1.

Simple but elusive compounds of the type Fe2(SR)2(CO)6.

In this paper, we report a new approach to obtaining some of the aforementioned elusive targets. The guiding hypothesis was that stable thioketones (unlike thioformaldehyde), might add to Fe2(S2)(CO)6. The photoinduced additions of ethylene and CO to Fe2(S2)(CO)6 afford Fe2(S2C2H4)(CO)6 and Fe2(S2CO)(CO)6, respectively.[7] The reaction has been extended to other alkenes.[8] These photoadditions probably proceed via the diferrous sulfide Fe2(S)2(CO)6, an excited state of Fe2(S2)(CO)6.[9]

Results and Discussion

We confirmed that Fe2(S2)(CO)6 does not readily react with Ph2CS thermally. This nonreactivity was easily checked, because the thione is deep blue. More promising results were obtained upon UV irradiation of a toluene solution of Fe2(S2)(CO)6 (90 mg) and an equimolar amount of Ph2CS (50 mg). The reaction was conducted using an LED emitting at 365 nm to give the targeted adduct [Equation (1)].

After ca. 1 h, the red product was obtained in 44 % yield after purification by column chromatography. The new compound 1 exhibited an FT-IR spectrum [2080 (s), 2046 (vs), 2007 (vs) cm−1] that closely (±5 cm−1) resembled the spectrum for Fe2(S2)(CO)6. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were consistent but not informative, but the EI-MS data showed a progression of peaks for Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6–n at m/z = 513.8 – n(28), which are

|

(1) |

assigned to [M – n CO]+ for n = 1–6. Once isolated, 1 is robust in air and ambient light.

To test the generality of the new reaction, we also investigated the photoaddition of Fe2(S2)(CO)5(PPh3)[8c] to thiobenzophenone. This reaction proceeded as above to give the adduct Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)5(PPh3) (2) in 45 % isolated yield. The 31P NMR spectrum of the adduct confirmed the presence of a single species with a signal at δ(31P) = 70.6 ppm, distinct from that of the parent Fe2(S2)(CO)5(PPh3) [δ(31P) = 60.81 ppm]. The reaction did not produce SPPh3, in contrast to a related reaction below.

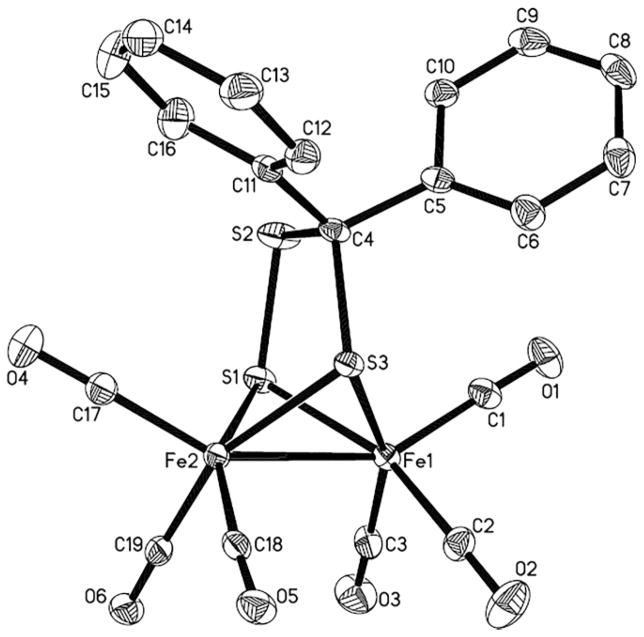

The structure of 1 was confirmed crystallographically (Figure 1). The molecule has idealized Cs symmetry but no crystallographically imposed symmetry. The compound adopts the now familiar butterfly structure with six terminal CO ligands. The CS3 bridge is planar.

Figure 1.

Structure of Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6 (1) with thermal ellipsoids drawn at the 50 % probability level. Selected distances [Å] and angles [°]: Fe(1)–Fe(2) 2.5068(6), Fe(1)–S(1) 2.2256(10), Fe(1)–S(3) 2.2427(9), S(1)–S(2) 2.0630(13), S(2)–C(4) 1.847(3), C(4)–S3 1.856(3); S(1)–Fe(1)–S(3) 81.40(3), S(1)–S(2)–C(4) 102.24(11), S(2)–C(4)–S(3) 109.41(16).

The reaction of thiobenzophenone with Fe2(S2)(CO)6 prompted investigation of its reaction with Fe3S2(CO)9, the other main Fe-S-CO cluster.[10] The diphenylmethanedithiolate has been obtained in 5–25 % yield by the reaction of thiobenzophenone with Fe2(CO)9 and Fe3(CO)12.[11] These reactions also produce several other products, including Fe3S2(CO)9. From the perspective of stoichiometry, this triiron cluster is a logical precursor to Fe2(S2CPh2)(CO)6. A reaction between Fe3S2(CO)9 and excess Ph2CS could only be induced in refluxing toluene, but the desired 3 was only obtained in ca. 10 % yield [Equation (2)].

| (2) |

This result suggests that 3 is not produced via the Fe3S2 cluster. Indeed, the intermediacy of the dithiirane Ph2CS2 has been proposed for related reactions.[11b,11c,12]

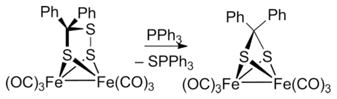

A more rational route to 3 involves the desulfurization of the perthiolate 1. Indeed, treatment of a CH2Cl2 solution of 1 with 1 equiv. of PPh3 at room temperature gave 3 in 85 % isolated yield [Equation (3)].

|

(3) |

The coproduct was SPPh3. The product was identical to that obtained in low yield from Fe3S2(CO)9.

Conclusions

The synthetic chemistry of Fe-S-CO compounds is very old,[13] and the biological chemistry of related materials is possibly ancient.[14] Given this rich context, new routes to fundamental derivatives of the Fe-S-CO series are always welcome. The addition of thioketones to Hieber’s classic Fe2S2(CO)6 [15] should encourage the development of photoadditions or other hetero-alkenes, hopefully opening new opportunities for this fascinating area.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Spectroscopic instrumentation and methodology have been described.[16] 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (162 MHz) spectra were referenced to residual solvent relative to TMS. 31P{1H} NMR (202 MHz) spectra were referenced to external 85 % H3PO4. Crystallographic data were collected using a Siemens SMART diffractometer equipped with an Mo-Kα source (λ = 0.71073 Å). The preparation of starting reagents are mentioned above, and Ph2CS was obtained using Lawesson’s reagent.[17] CCDC 1476511 (for 1), and 1440460 (for 3) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6 (1)

A mixture of Fe2S2(CO)6 (90 mg, 0.25 mmol) and Ph2CS (50 mg, 0.25 mmol) was dissolved in dry toluene (70 mL) in a Pyrex Schlenk tube. The reaction mixture was photolyzed at 365 nm for ca. 1 h. After filtration, the resulting deep-green filtrate was concentrated under vacuum to afford a viscous residue. The residue was chromatographed on silica gel eluting with hexane/CH2Cl2 (10:1). The main red band (the second band) was concentrated to give the product, a red solid. Yield 60 mg (44 %). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.64 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 4 H, ArH), 7.28 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 6 H, ArH) ppm. 13C NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 207.5 (FeCO), 143.3 (ArC), 128.57, 128.55, 128.4 (ArCH), 89.8 (S2CPh2) ppm. FT-IR (CH2Cl2): ν̃CO = 2080 (vs), 2046 (vs), 2007 (vs) cm−1. EI-MS: m/z = 513.8 [M – CO]+, 485.8 [M – 2 CO]+, 457.8 [M – 3 CO]+, 401.9 [M – 5 CO]+, 373.9 [M – 6 CO]+. C19H10Fe2O6S3 (541.8): calcd. C 42.09, H 1.86; found C 41.77, H 1.57. The single crystal for X-ray analysis was grown by slow concentration of a concentrated pentane solution.

Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)5(PPh3) (2)

A mixture of Fe2S2(CO)5(PPh3) (90 mg, 0.15 mmol) and Ph2CS (30 mg, 0.15 mmol) was dissolved in dry toluene (60 mL) in a Pyrex Schlenk tube. The mixture was irradiated at 365 nm for ca. 1 h. After the solvent had been removed under vacuum, the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel eluting with hexane/CH2Cl2 (4:1). The intense red band (the third) was concentrated to give the product as a red solid. Yield 50 mg (43 %). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.58–7.44 (br. d, 16 H, ArH), 7.26–7.13 (m, 9 H, ArH) ppm. 31P NMR (202 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 70.6 (s) ppm. FT-IR (CH2Cl2): ν̃CO = 2045 (vs), 1991 (vs), 1975 (s). 1934 (m) cm−1.

Fe2(S2CPh2)(CO)6 (3)

Method 1: A mixture of Fe2(S3CPh2)(CO)6 (50 mg, 0.09 mmol) and PPh3 (27 mg, 0.10 mmol) was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (10 mL). The reaction solution was stirred at room temperature until the reaction was completed (3 h) as indicated by FT-IR spectroscopy. After the solvent had been removed under vacuum, the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel eluting with hexane/CH2Cl2 (10:1). The intense red band (the first band) was collected and concentrated to yield the product, an orange-yellow solid. Yield 40 mg (87 %). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 7.33 (br. s, 8 H, ArH), 7.23 (br. s, 2 H, ArH) ppm. 13C NMR (162 MHz, CD2Cl2): δ = 208.7 (FeCO), 150.2 (ArC), 129.0, 128.1, 123.7 (ArCH), 95.1 (S2CPh2) ppm. FT-IR (CH2Cl2): ν̃CO = 2076 (vs), 2039 (vs), 2000 (vs) cm−1. EI-MS: m/z = 510.1 [M]+, 482.1 [M – CO]+, 454.1 [M – 2 CO]+, 426.1 [M – 3 CO]+, 398.1 [M – 4 CO]+, 370.1 [M – 5 CO]+, 342.0 [M – 6 CO]+. Method 2: A mixture of Fe3S2(CO)9 (97 mg, 0.20 mmol) and Ph2CS (40 mg, 0.20 mmol) was dissolved in dry toluene (100 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 90 °C for 2 h and then at reflux for 1.5 h. After the solvent had been removed under vacuum, the residue was purified by chromatography on silica gel, eluting with hexane/CH2Cl2 (10:1). The intensely red band (the first band) was collected and concentrated to yield the product as an orange-yellow solid. Yield 10 mg (10 %).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the US National Institutes of Health and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21301160).

Footnotes

Supporting information and ORCID(s) from the author(s) for this article are available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201600366.

References

- 1.Rauchfuss TB. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:2107–2116. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Li Y, Rauchfuss TB. Chem Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00669. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfel U-P, Pétillon FY, Schollhammer P, Talarmin J, Weigand W. In: Bioinspired Catalysis. Schollhammer P, Weigand W, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2014. pp. 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Broadhurst PV. Polyhedron. 1985;4:1801–1846. [Google Scholar]; b) Shi YC, Cheng HR, Yuan LM, Li QK. Acta Crystallogr, Sect E. 2011;67:m1534. doi: 10.1107/S1600536811041936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Nekhaev AI, Kolobkov BI, Tashev MT, Dustov KB, Aleksandrov GG. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR Ser Khim. 1991:930–934. [Google Scholar]; b) Nametkin NS, Tyurin VD, Kolobkov BI, Krapivin AM. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR Ser Khim. 1983:1212–1213. [Google Scholar]; c) Nekhaev AI, Kolobkov BI, Tashev MT, Dustov KB, Aleksandrov GG. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR Ser Khim. 1989;1705 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schenk WA. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:1209–1219. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00975j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seyferth D, Womack GB, Gallagher MK, Cowie M, Hames BW, Fackler JP, Mazany AM. Organometallics. 1987;6:283–294. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messelhäuser J, Gutensohn KU, Lorenz IP, Hiller W. J Organomet Chem. 1987;321:377–388. [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Kramer A, Lorenz IP. J Organomet Chem. 1990;388:187–193. [Google Scholar]; b) Kramer A, Lingnau R, Lorenz IP, Mayer HA. Chem Ber. 1990;123:1821–1826. [Google Scholar]; v) Westmeyer MD, Rauchfuss TB, Verma AK. Inorg Chem. 1996;35:7140–7147. doi: 10.1021/ic960728+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silaghi-Dumitrescu I, Bitterwolf TE, King RB. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:5342–5343. doi: 10.1021/ja061272q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams RD, Babin JE. Inorg Chem. 1986;25:3418–3422. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Alper H, Chan ASK. J Am Chem Soc. 1973;95:4905–4913. [Google Scholar]; b) Daraosheh AQ, Apfel UP, Görls H, Friebe C, Schubert US, El-Khateeb M, Mloston G, Weigand W. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012:318–326. [Google Scholar]; c) Daraosheh AQ, Görls H, El-Khateeb M, Mloston G, Weigand W. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2011:349–355. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Windhager J, Rudolph M, Bräutigam S, Görls H, Weigand W. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2007:2748–2760. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reihlen H, Friedolsheim AV, Oswald W. Justus Liebigs Ann Chem. 1928;465:72–96. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wächtershäuser G. In: Bioinspired Catalysis. Weigand W, Schollhammer P, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hieber W, Gruber J. Z Anorg Allg Chem. 1958;296:91–103. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carroll ME, Chen JZ, Gray DE, Lansing JC, Rauchfuss TB, Schilter D, Volkers PI, Wilson SR. Organometallics. 2014;33:858–867. doi: 10.1021/om400752a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen BS, Scheibye S, Nilsson NH, Lawesson SO. Bull Soc Chim Belg. 1978;87:223–228. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.