Abstract

Background:

Cystic angiomatosis (CA) is a rare disorder causing bony cysts. It displays some similarity to Gorham–Stout disease (GSD), but has a much better local prognosis, despite the larger number of cysts. These 2 conditions also differ in terms of their location, visceral involvement, and response to treatment.

Methods:

We report 4 cases of CA, including 1 sclerosing form, which we compare with cases from a literature review performed with PRISMA methodology.

Results:

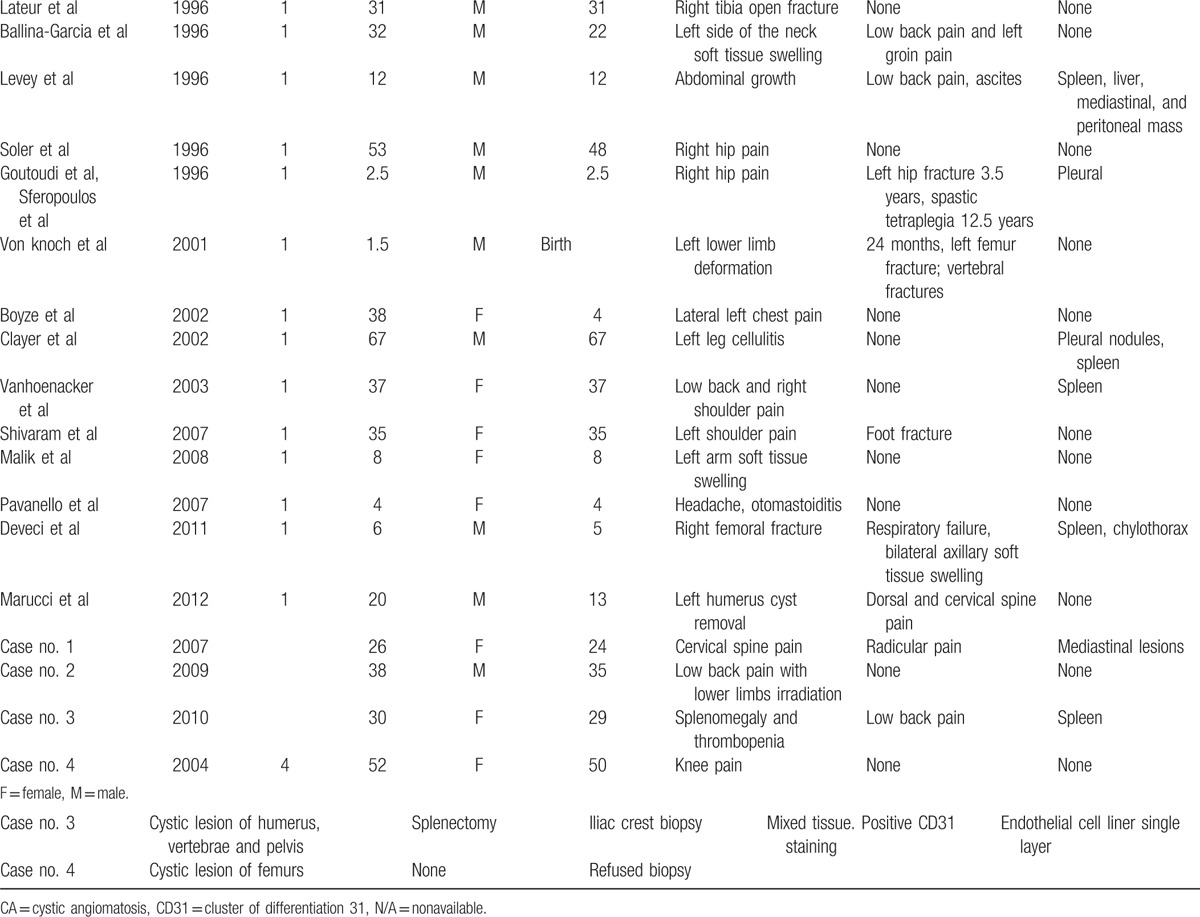

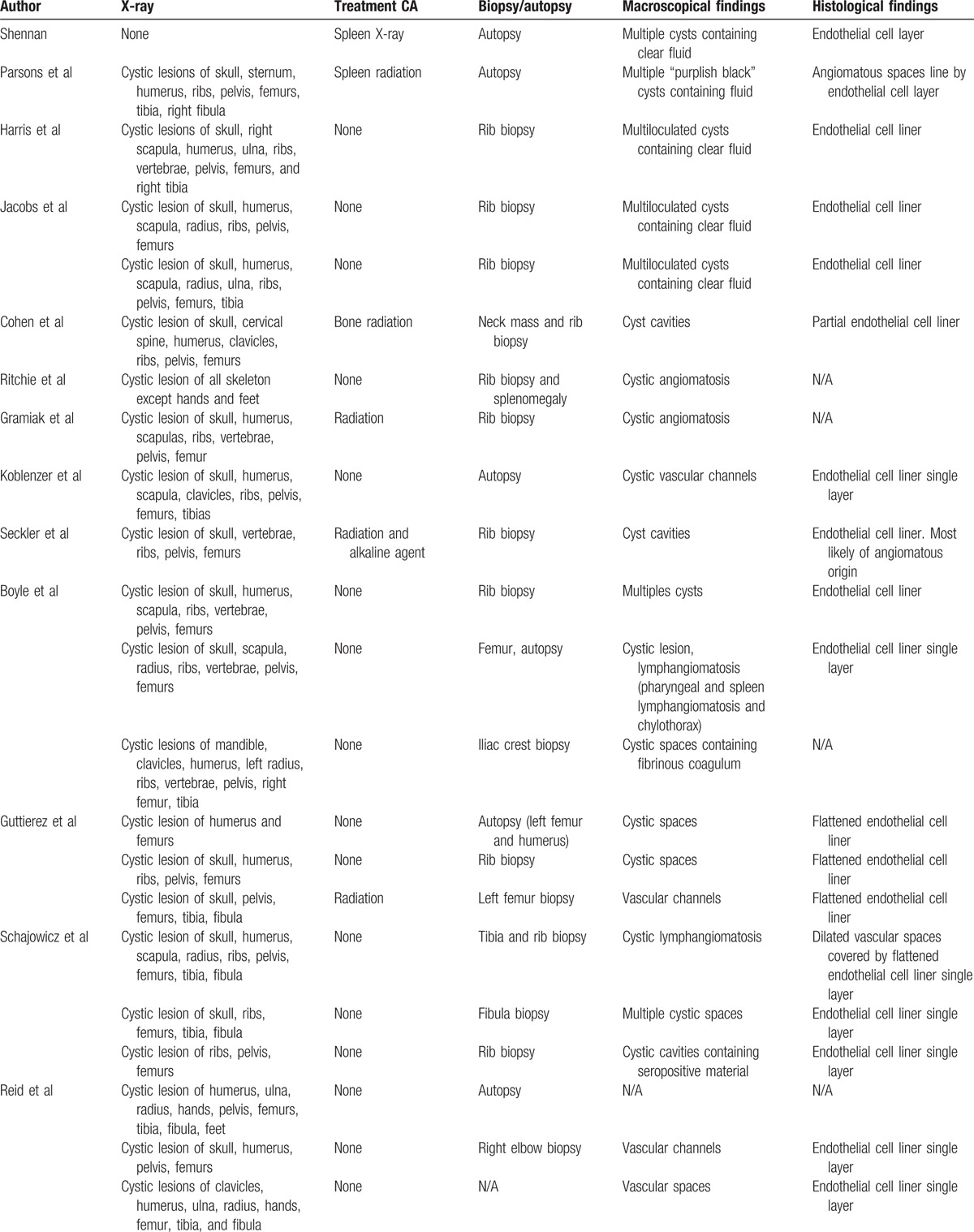

We reviewed 38 articles describing 44 other patients. Mean age at diagnosis for the 48 patients (our 4 patients + the 44 from the review) was 22.5 years, and 28 of the patients were men. The femur was involved in 81% (n = 39), the pelvis in 73% (n = 35), the humerus in 52% (n = 25), the skull in 48% (n = 23), and the vertebrae in 44% (n = 21). Visceral lymphangiomatosis (either clinical, or detected on autopsy) was also reported in 35% (n = 18) of the patients. The spleen was the most frequently involved organ (n = 12), followed by the lungs and pleura (n = 8). Liver cysts and/or chylothorax were rarely reported (5 cases), but were invariably fatal. Radiation therapy on bone or soft tissue masses was ineffective, as was interferon alpha, in the 2 patients in which this drug was tested. The efficacy of bisphosphonate was at best equivocal.

Conclusion:

The progression of CA is unpredictable and treatments effective against GSD, such as bisphosphonates and radiotherapy, have proved ineffective for this condition. New treatments are thus urgently required.

Keywords: bone cysts, cystic angiomatosis, Gorham–Stout disease, lymphangiomatosis, osteolysis

1. Introduction

Cystic angiomatosis (CA) is a rare disease characterized by multifocal bony cysts with a honeycombed or “bubble” appearance, but without aggressive osteolysis. It varies in severity from frequent mild forms with skeletal abnormalities discovered fortuitously on X-rays, to rare severe forms with widespread visceral lymphangiomatosis causing early death.[1] Men seem to be more frequently affected than women, with a sex ratio of 2:1.[2 3]

Imaging reveals typical features. The lesions are multifocal, well-defined, skeletal intramedullary cysts, with a relatively well-preserved bony cortex,[4] and no periosteal reaction, even if the cysts are located just beneath the cortex. The cysts are oriented over the long axis of the bone, and are classically surrounded by a sclerotic peripheral rim.[5] On macroscopic examination, the cysts may appear empty or filled with a colorless or “pinkish” bloody proteinaceous material.[6 7] On histological examination, vascular channels with a single layer of flattened endothelial cells are typically observed.[2]

As these cells are lymphatic, some authors have suggested that this disorder should be called “generalized lymphatic abnormality” (GLA) rather than “cystic angiomatosis” (CA),[8 9] particularly as tissues other than bone may be affected. However, although GLA does indeed commonly affect bone, this condition is often both congenital and fatal.[10] We restricted our review to patients with typical CA, which remains a benign disorder in most cases.

Neither peripheral soft tissue involvement nor a periosteal reaction are observed in CA,[1] facilitating differential diagnosis from metastasis, multiple myeloma, or other malignant conditions. CA has a number of features in common with Gorham–Stout disease (GSD), but it differs in several aspects. CA has a much better prognosis, the rim of the cysts has a sclerotic appearance on X-rays and sclerosing lesions rather than osteolysis are sometimes observed. These elements suggest a possible difference in the pathogenesis of these 2 conditions, although they are probably closely related. We report here 4 new cases of CA diagnosed in the past 10 years at a single university hospital, including 1 case with an osteosclerotic pattern, which we have compared with previously reported cases of CA.

2. Methods

We carried out a systematic literature review with the PubMed and Medline databases, by the PRISMA method.[11]

We selected articles published in English, with no restriction on the date of publication. The first author screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. The second author was consulted if the diagnosis seemed unclear, and articles were included if both authors agreed. Articles were excluded if important information (clinical or imaging features) was missing.

The key words used for the search were: polycystic, and/or cystic and bone, and/or skeletal, and/or skeleton, and angiomatosis or hemangiomatosis.

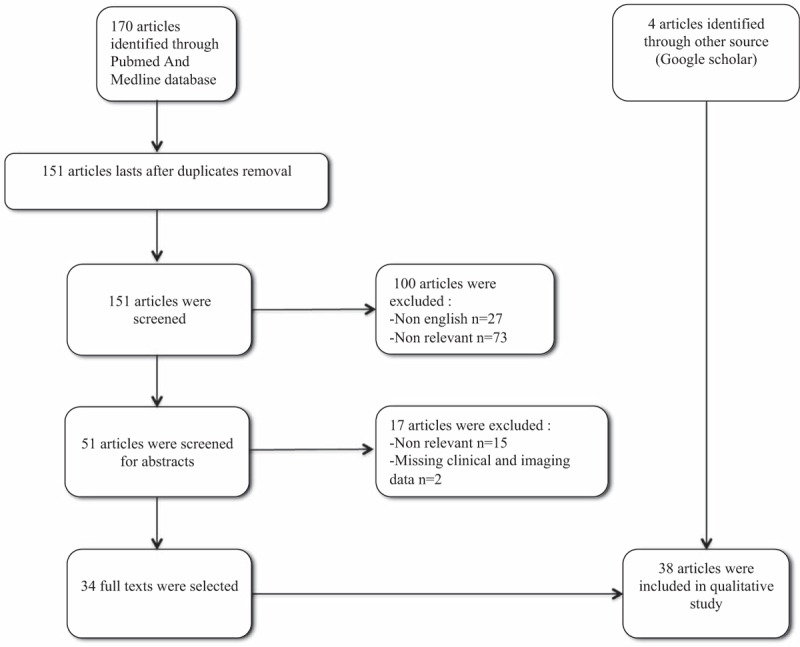

We identified 170 potentially relevant articles in PubMed and Medline databases. After the removal of duplicates, 151 articles remained, 100 of which were excluded (73 articles were considered nonrelevant once the title and abstract had been read, and 27 articles were published in a language other than English); 51 abstracts were screened, fifteen of which were excluded as they were considered nonrelevant. We therefore assessed 36 full-text articles for eligibility. Two of these articles were excluded because they contained incomplete clinical and imaging data. We finally retained 34 articles for this study. Another 4 articles were identified with Google scholar, all of which were included in this study with the agreement of all authors, leading to 38 articles (Fig. 1). Informed consent was collected for the 4 patients before we report their case in this article.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3. Observation/results

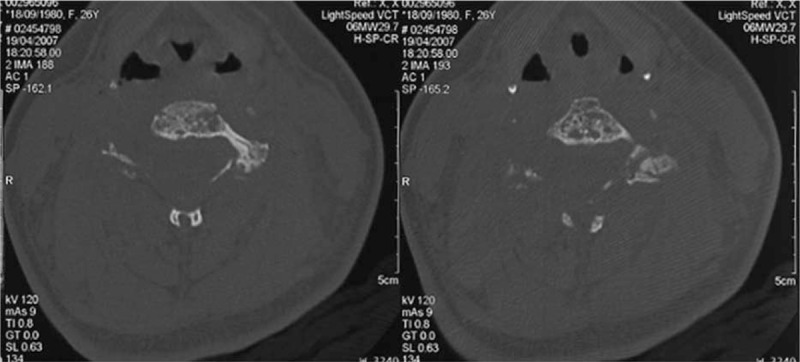

The first case was a 26-year-old woman referred to us in 2006 for severe neck pain of 1 year duration. She had a medical history of untreated asthma and depression. Clinical examination showed neither stiffness nor associated radicular pain. The general examination was normal. Blood analysis revealed only lymphopenia (500 lymphocytes/mm3 (N = 1500–4000)), principally concerning CD4+ (141/mm3; normal range (N = 500–1200/mm3), and CD8+ cells (189/mm3; N = 300–700/mm3)) T cells, with B- and natural killer cells (NK cells) levels in the normal range. Cervical X-rays and computerized tomography scan (CT scan) of the cervical spine showed spontaneous C5–C6 vertebral dislocation with osteolytic C5 and C6 posterior arches and zygapophyseal joint cystic lesions (Figs. 2–4). The patient underwent emergency laminectomy surgery and posterior osteosynthesis. No malignant cells were found on histological examination. The bone marrow spaces appeared to be filled with fibrous and edematous tissue associated with vascular structures consistent with hemangioma. No other bone or visceral lesions were found. No neurological impairment occurred.

Figure 2.

Case 1. Cervical spine X-ray with anterioposterior and lateral views. C5–C6 dislocation. Osteolytic bony cysts resulting in a honeycomb appearance of the vertebral bodies of C5 and C6 and the C5–C6 zygapophyseal joints. Note the preserved bony cortex and the lack of periosteal reaction.

Figure 4.

Case 1. Transverse CT imaging of the cervical spine. Osteolytic bony cysts on the vertebral bodies of C5 and C6 with a honeycomb appearance. Note the preserved bony cortex.

Figure 3.

Case 1. Axial CT imaging of the cervical spine. Osteolytic bony cysts on the vertebral bodies of C5 and C6 with a honeycomb appearance (white arrows). Note the preserved bony cortex.

Four months after surgery, the patient reported a recurrence of cervical pain and C6 radicular pain. Clinical examination showed no neurological impairment. Cervical X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed progression of the lytic intravertebral lesion at C5 and a spontaneous recurrence of C5–C6 dislocation. The patient underwent emergency surgery again, with C4–C7 arthrodesis and anterior cervical osteosynthesis. Radicular and cervical pain improved after surgery and remained stable thereafter.

Bisphosphonate treatment was initiated 3 months after surgery. Zoledronic acid (4 mg) was administered intravenously after vitamin D intake, once every 6 months for 2 years. In 2009, the patient complained of acute severe cervical spine pain radiating to the face. MRI showed prevertebral soft tissue swelling at C2 compressing the left second vertebral nerve. This pain improved spontaneously. In 2011, mediastinal cystic lesions were detected on a control MRI scan, with no associated symptoms. A Positron emission tomography (PET) scan was then performed to assess tumor mass, but no 18-fluorodesoxyglucose (FDG) uptake was observed. The patient has a routine control MRI scan once per year, and no relapse has since occurred. The patient had received 9 bisphosphonate infusions (once per year) by 2015. These infusions were well-tolerated and stabilized the bony lesions.

The second case was a 38-year-old man with low back pain of 3 years’ duration radiating to the legs and the right buttock, without causing a limp. He had a history of smoking and depression. The results of physical and biological examinations were normal. Lumbar and pelvic X-rays and CT scans showed cystic lesions of both the ilium and left sacral bones, with a sclerotic rim and partial cortical osteolysis of the right iliac crest (Fig. 5). MRI was therefore performed. The cystic lesions yielded a high-intensity signal on T2-weighted sequences and an isointense signal on T1-weighted sequences, suggestive of liquid cysts with a fatty component. As the pain was disabling, the patient underwent pelvic cementoplasty in 2008, leading to partial pain relief. In 2009, the low back pain increased with bilateral S1 radiation. The patient underwent pelvic cementoplasty again, with better results. A right iliac crest biopsy was performed during the first cementoplasty procedure, but no meaningful histological analysis was possible because the sample obtained was too small. The patient also complained of severe headaches. He therefore also underwent brain and spinal cord angio-MRI, which showed that there were no aneurysms present. No other visceral involvement was suspected. In 2013, 7 years after diagnosis, the patient's lesions were completely stable on X-ray evaluation.

Figure 5.

Case 2. CT imaging of the pelvis without contrast product injection. Cystic osteolytic bony lesions with a sclerotic rim within the right iliac crest and the left sacral bone. Note the exceptional cortical osteolysis of the right iliac crest (black arrow).

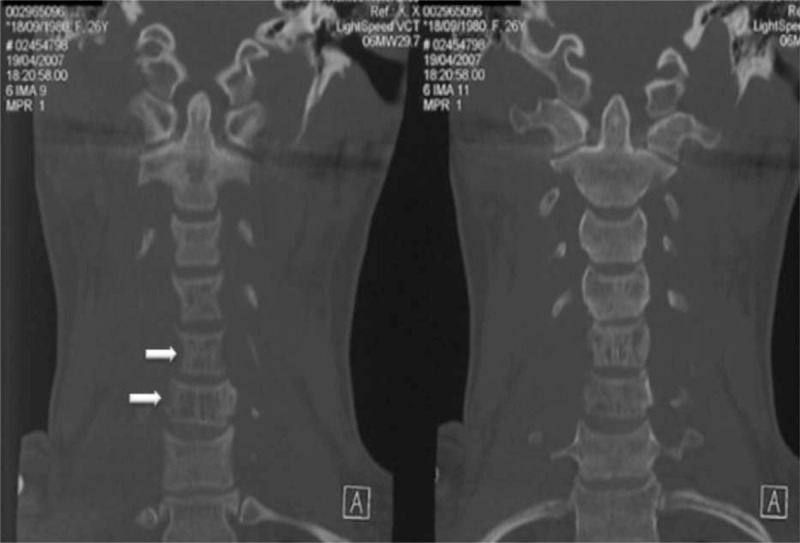

The third case was a 30-year-old woman referred to us in 2009 for heterogeneous lytic and sclerosing cystic bony lesions discovered on a routine X-rays examination. She had a history of spontaneously resolving thrombopenia during a pregnancy in 2008. A clinical examination in 2009 revealed splenomegaly. The patient was otherwise healthy. Blood analysis results were normal, with the exception of thrombocytosis (476 × 109 platelets per liter; N = 150–400 × 109/L). Ultrasound measurements showed the spleen to be more than 20 cm long. X-rays and PET scans were performed for a more detailed assessment of splenomegaly. These examinations revealed the presence of lytic cystic lesions of the T12 vertebra, sclerosing lesions of the L2 and L5 lumbar vertebrae and poor vascular uptake (standardized uptake value (SUV) max of 2.3; Fig. 6), together with lytic lesions of the head of the left humerus and the right iliac crest. A diagnosis of histiocytosis X was suggested and the patient underwent splenectomy. Angiomatous features were observed on histological examination of the spleen. Iliac crest biopsy showed mixed tissue, with positive staining for CD31. Vascular uptake at sclerosing spots was observed on a bone scan (Fig. 7). MRI revealed features typical of CA (Fig. 8). The patient underwent her first intravenous infusion of 5 mg zoledronic acid, after vitamin D reloading, in 2010. The vertebral lesions remained stable on a spinal CT scan performed 4 months later.

Figure 6.

(A–C) Case 3. Sagittal spine (A), anteroposterior spine (B), and anteroposterior pelvic (C) X-rays. Sclerosing lesions of the L2 and L5 vertebral bodies and right iliac crest, corresponding to the areas of vascular uptake on the bone scan.

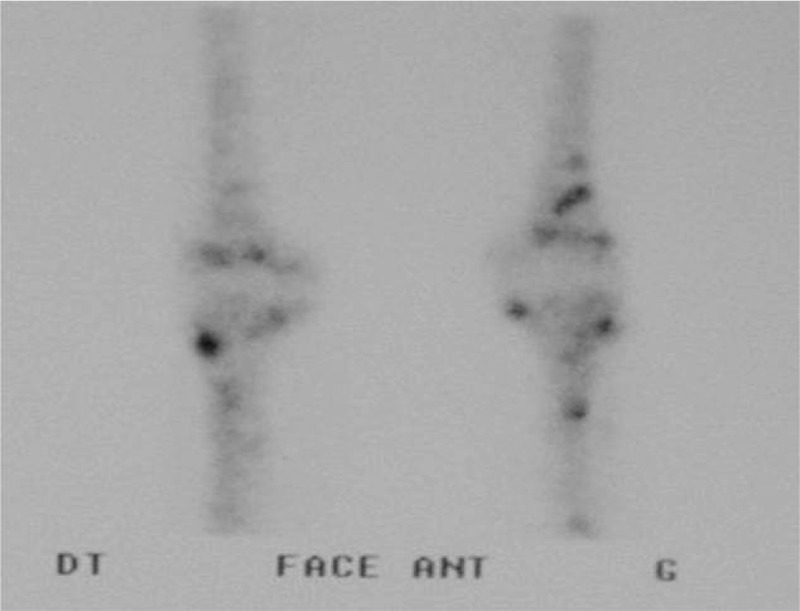

Figure 7.

Case 3. Bone scan. Vascular uptake of the T12 vertebra, the L2 and L5 lumbar vertebrae, the right iliac crest, and the head of the left humerus.

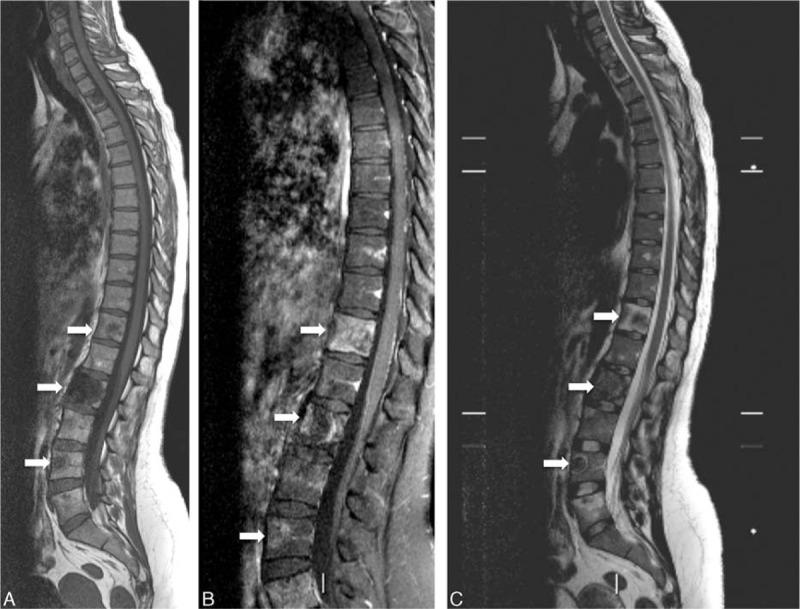

Figure 8.

(A–C) Case 3. Thoracic and lumbar spine magnetic resonance images. Heterogeneous cystic vertebral lesions, well-defined, with a preserved bony cortex (white arrows). Low-intensity signal with pronounced rim enhancement after gadolinium injection of the second thoracic vertebral body, L2 and L4 lesions on T1-weighted sequences (A and B), and high-intensity signal on T2-weighted sequences (C). Note the sclerotic rim of the lesions of the L2 and L4 vertebrae (C).

The fourth patient was a 52-year-old woman who was referred for bilateral knee joint pain. She had no relevant personal or familial medical history. Clinical examination was normal with the exception of the presence of widespread brown nevi. An X-ray of the knees was normal, but a 99mtc bone scan revealed vascular uptake in both knees, with no other abnormalities (Figs. 9 and 10). Knee MRI revealed the presence of multiple cystic lesions of variable size (Fig. 11). On T2 sequences, a high-intensity signal was observed in the cystic areas, suggesting that the cysts contained liquid (Fig. 11). Biopsy was proposed several times, but was systematically refused by the patient. A diagnosis of CA was proposed on the basis of the radiological and clinical features. The bony cysts stabilized during follow-up, with no further growth of existing cysts and no new cysts appearing. The pain improved spontaneously. Three years later, the patient presented a nodular lesion of the head of the pancreas. A biopsy was carried out and histological findings were consistent with glucagonoma. The patient underwent surgery and experienced no further relapse. After 6 years of follow-up, 2 pulmonary nodules 2 to 4 mm in diameter and 1 hepatic nodule 5 mm in diameter were identified on a full-body CT scan. No progression of these nodules was observed on a full-body CT scan carried out 2 years later. The patient is still alive, 18 years after diagnosis.

Figure 9.

Case 4. Normal right knee X-ray.

Figure 10.

Case 4. Bone scan. Vascular uptake at the distal ends of the femurs and at the proximal ends of the tibias.

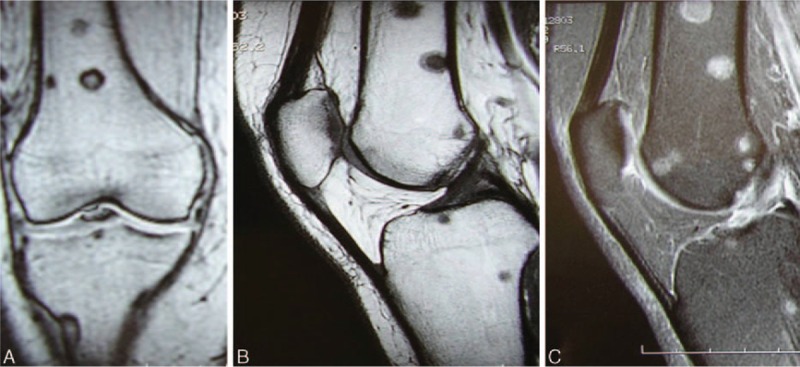

Figure 11.

(A–C) Case 4. Knee magnetic resonance images. (A) Frontal T1-weighted sequence. (B) Sagittal T1-weighted sequence. Multiple sharply defined bony lesions on the epiphysis and metaphysis on both sides of the joint (femoral and tibial) with high signal intensity in T2-weighted sequences (C).

4. Discussion and review

We included 38 articles in the review. These articles described 44 patients. Together with our 4 patients, we therefore considered data for 48 patients in total. The mean age of these patients was 22.5 years, and there were 28 men and 20 women. The sex ratio was thus 1.4, indicating that men were more likely than women to be diagnosed with CA.

CA is a rare nonmalignant vascular tumor of the bone causing skeletal cysts, which are often associated with extraskeletal cysts. Parsons and Ebbs[7] provided the first description of this condition in 1940, in a 13-year-old girl referred for presternal and supraclavicular soft tissue swelling. Clinical examination revealed spleen enlargement. X-rays revealed the presence of several bony cystic lacunae in the skull, sternum, humeri, ribs, pelvis, femurs, tibia, and right fibula. The patient died of acute respiratory failure. Cysts were found in the spleen, lungs, and liver on autopsy. Histological examination of bony and soft tissues showed “purplish black cysts” containing fluid, with “angiomatous spaces” lined by a layer of endothelial cells. Several authors subsequently described similar cases of CA with or without visceral involvement (Tables 1 and 2 ).

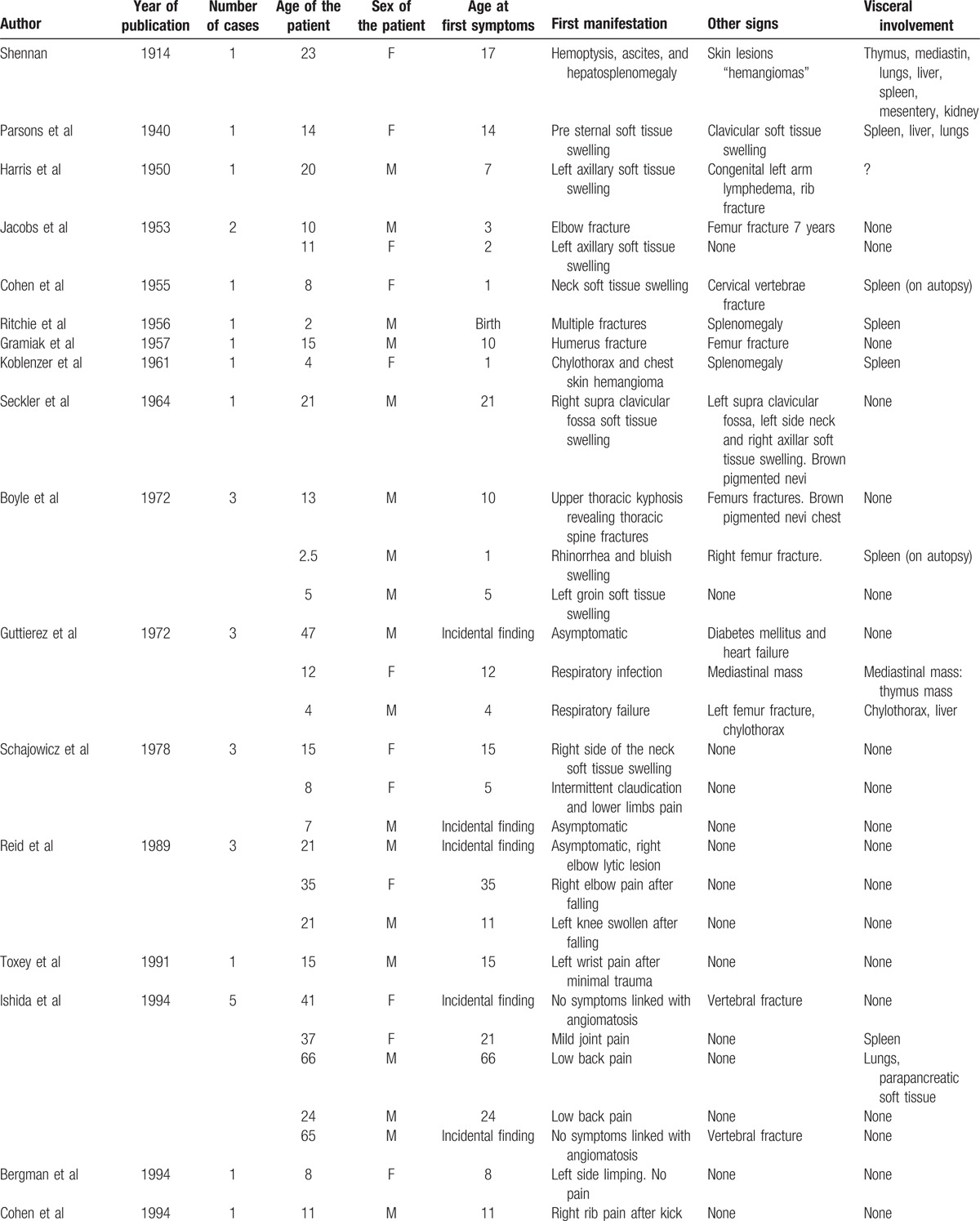

Table 1.

Forty-eight cases clinical features.

Table 1 (Continued).

Forty-eight cases clinical features.

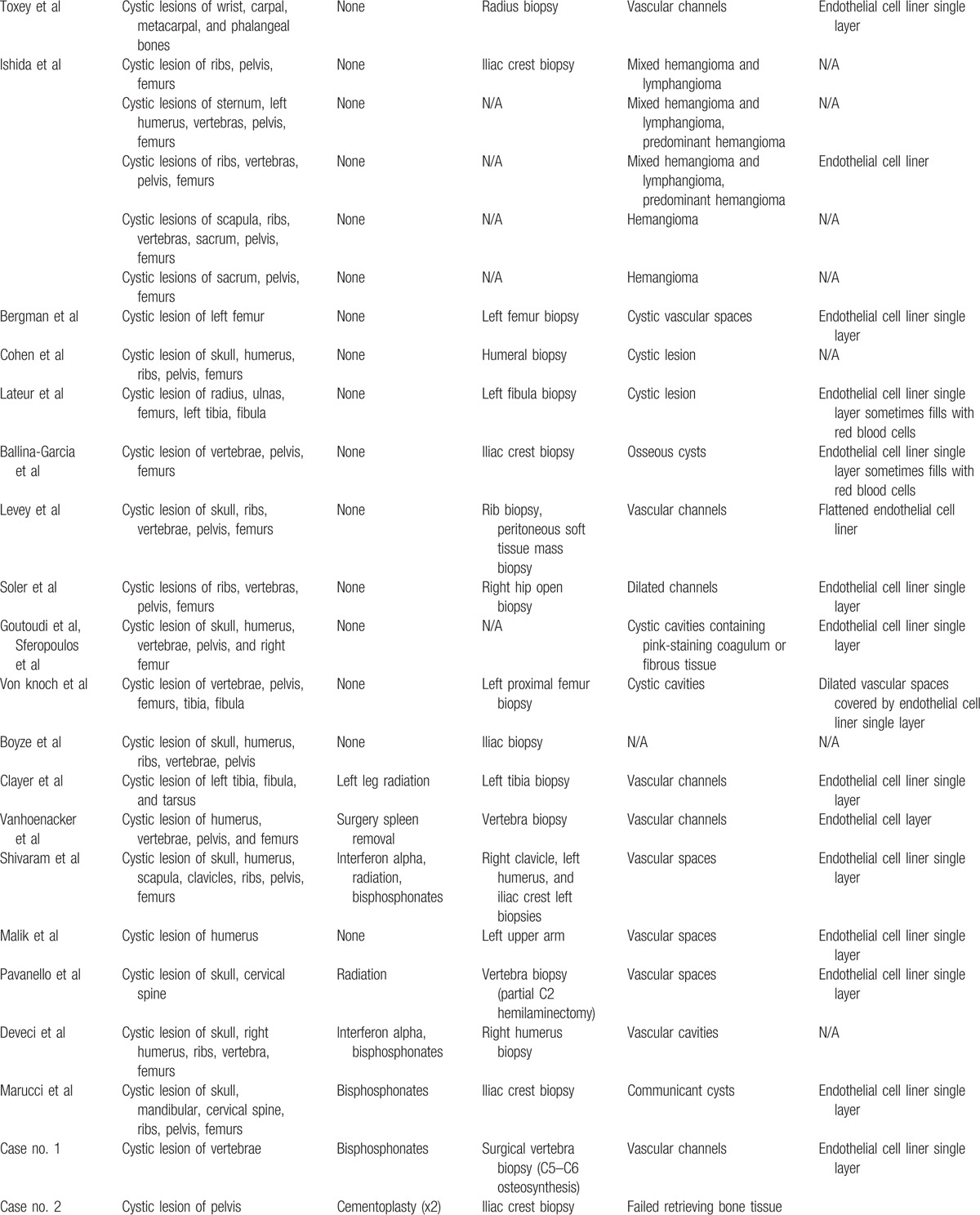

Table 2.

Forty-eight cases radiological and histological features.

Table 2 (Continued).

Forty-eight cases radiological and histological features.

4.1. Epidemiology

The first manifestations occur in the first few decades of life, mostly during puberty. However, some authors have reported cases with a late onset,[5 12–14] diagnosed after the age of 60 years, suggesting that there may be a second frequency peak. One of our patients was diagnosed at the age of 52 years. The mean age of the 48 patients analyzed here was 22.8 years. Male predominance has been reported, but is not universally accepted, as some authors have reported the frequency of this condition to be similar in men and women.[15 16] In our review, the sex ratio was 3:2, still in favor of men but lower than the 2:1 ratio previously reported in the reviews by Boyle[2] and Levey et al.[1]

4.2. Characteristic features

4.2.1. Skeletal involvement

Skeletal cysts were present in all of the cases described and analyzed. The long bones, skull, spine, and pelvis were the principal bones involved, as previously reported.[2 6 14 17] Femurs were involved in more than 81% of cases (n = 39), the pelvis in 73% (n = 35), the humeri in 52% (n = 25), the skull in 48% (n = 23), and vertebrae in 44% (n = 21).

In rare cases, carpal, metacarpal, phalange, and tarsus bones were also involved.[12 18 19] Cysts are more likely to occur at these sites in GSD, but, in these 3 cases, the features observed on imaging were completely consistent with CA.[12 18 19] However, in the case reported by Toxey and Achong,[19] the bony cysts in the hand progressed very rapidly and no polyostic spread was observed. As these features are more commonly seen in GSD, some clinical presentations may be intermediate between these 2 conditions.

CA cysts are often completely asymptomatic, and diagnosis is therefore often fortuitous, on X-rays taken for other reasons. Growth plate closure and remodeling during growth remain unaffected.[15 18] However, the cysts can thin the bones such that they are more susceptible to pathologic fractures, which may lead to CA diagnosis. Cysts can also cause bone deformation in adults, resulting in scoliosis, lower limb shortening, weakness, limping, or pain, depending on their location.

4.2.2. Skin and soft tissue swelling

Some authors have described cutaneous involvement, with brown nevi[2 3 20] or subcutaneous hemangiomas[21 22] associated with CA. One of our 4 patients (Case 4) presented with diffuse brown nevi. This feature may be coincidental or a sign of the condition.

4.2.3. Visceral involvement

We identified 18 patients with reported visceral lymphangiomatosis (either clinical, or found on autopsy), accounting for 35% of the cases.[2 17 23 24] The spleen was the organ most frequently involved, in 25% of cases (n = 12). The lungs and pleura were less frequently reported to be involved (17%, n = 8). Liver cysts and/or chylothorax were reported in only 5 cases, but were invariably lethal.[1 7 17 22 25] Spleen involvement has also been reported in GLA.[9]

4.2.4. Complications

Cervical spine cysts, in particular, have a number of potential complications. One of our patients (Case 1) presented with a C5–C6 dislocation requiring emergency surgery to prevent death by spinal cord compression. Some of the other patients reported in previous studies also had cervical spine cysts,[16 26–30] and 1 died from spinal cord compression.[26]

Splenomegaly has its own complications, including intermittent pain, rupture and consumption coagulopathy or bleeding.[17 31 32] One of our patients (Case 3) developed thrombocytopenia during pregnancy. This condition resolved spontaneously, but splenomegaly was detected on physical examination 1 year later, leading to the diagnosis of CA.

4.2.5. Biological features

There are no specific biological features associated with CA. Some authors have reported an increase in alkaline phosphatase (PAL) levels,[14 27 29–31] consistent with the substantial changes to remodeling in bones affected by CA. CD4 and CD8 T-cell lymphopenia (without opportunist infection) was observed in one of our patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that this condition has been reported in association with CA.

4.2.6. Imaging features

4.2.6.1. X-ray and 99mtc bone scan

CA typically presents as multifocal well-defined intramedullary cysts with a sclerotic peripheral rim, a preserved bony cortex, and no periosteal reaction.[1] However, exceptions have been reported. For instance, our first patient experienced a spontaneous C5–C6 vertebral dislocation with osteolytic C5 and C6 posterior arches and zygapophyseal joint cystic lesions (Figs. 2–4), and our second patient presented with cortical osteolysis of the ilium (Fig. 5). This feature is very rare in CA, but the MRI scan was otherwise typical of this condition. To our knowledge, only one other author has described an isolated femoral neck cortical lytic cyst[33] in a patient with histological features of a biopsied lesion fully consistent with CA (cystic vascular spaces lined with a single layer of endothelial cells). The sclerotic rim may also be absent, especially in skull cysts.[27]

Other unusual radiological aspects have also been reported, including sclerosing cysts or osteosclerotic patchy areas within the cysts (Figs. 9–11).[5 12–14 18 31] In some patients, the radiological appearance of the osteoblastic lesions can mimic osteoblastic metastases.[14] In previous studies, patients presenting sclerosing forms of CA differed epidemiologically and clinically from the other patients. They were older, consistent with the bimodal distribution of the frequency of the disease with age.[14] It has been suggested that the disease begins with a phase of osteolysis, followed by a phase of stabilization, fibrous scarring, and osteoformation.[18] The different radiographic aspects observed for a single patient may, thus, correspond to different pathophysiological stages. Reid et al[18] described a familial case series in which more than 10 years of follow-up data were available for some patients. One of these patients displayed a shift from a lytic to a sclerosing appearance on X-ray.[18] Two of our patients (Cases 1 and 4) had asymptomatic cysts with heterogeneous lytic and sclerosing patterns. These cysts were more likely to present vascular uptake of 99mtc on bone scan, as previously reported.[14] Sclerosing bone around the cysts may underlie a wounding process involving greater vascularization and larger numbers of inflammatory cells.

Several bones may be affected in the same patient, and lytic CA can mimic many conditions: bone metastasis (either osteolytic or condensing), lymphoma, fibrous dysplasia, histiocytosis, brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism. CA with a condensing pattern may resemble mastocytosis, Bourneville tuberous sclerosis, or sarcoidosis.

4.2.6.2. MRI findings

MRI can be sufficient for the positive diagnosis of CA in typical cases.[24 33 34–36] Indeed, T2-weighted sequences almost always display a strong signal because of the liquid content of the cysts. The T1-weighted sequence signal obtained depends on cyst content: it may be weak (cysts containing serum), or strong (cysts containing blood).[37] Rim enhancement is often observed after gadolinium injection.[33]

4.2.6.3. PET scan

To our knowledge, this is the first report of the appearance of CA cysts on a PET scan. In one of our patients (Case 1) no uptake of 18-FDG was seen, and in the other (Case 4), 18-FDG uptake was observed, but with a low SUV (SUV max of 2.3), in lytic vertebral lesions.

4.2.7. Histological features

In all the cases reviewed, the basic histological appearance of the tissue examined was described as follows: vascular channels, vascular cysts, vascular spaces, vascular cavities, cystic cavities, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas or mixed. The cyst walls were always lined with a single layer of endothelial cells. The endothelial cells were mostly described as flattened. Some authors have suggesting that specific antibodies could be used to stain vessels, such as anti-CD31 or anti-FVIII antibodies.[34] The histological features of GSD and CA are very similar, with lymphatic vessels, rather than blood vessels, primarily affected in both conditions.[38]

4.3. From cystic angiomatosis to Gorham–Stout disease

GSD is also known as disappearing (or vanishing) bone disease, highlighting its main feature: massive and progressive osteolysis. Some authors have suggested that GSD and CA are part of the same disease entity, simply differing in terms of the severity of osteolysis. Indeed, histological findings are very similar for these 2 conditions, with cysts (in CA) or fibrous tissue (in GSD) separated by bony trabeculae covered with a single layer of flattened endothelial cells, with few cellular abnormalities, if any (contrasting with bone hemangiomas[2 15 39]). Similarly, lymphangiomatosis, rather than hemangiomatosis, is found in both conditions.[32] However, most authors agree that CA and GSD should be seen either as 2 separate conditions, or at least as being located at the 2 ends of a single spectrum. Indeed, despite the similarity of histological findings, the clinical features of the 2 conditions differ in several ways.

4.3.1. Better prognosis in cystic angiomatosis than in Gorham–Stout disease

The main difference is that GSD usually leads to progressive massive osteolysis resulting in cortical bone loss, and leading to severe deformations and disability,[39 40] whereas CA usually remains confined to the medullary cavity and does not progress. CA cysts are usually surrounded by a sclerotic rim, and bone lesions may present as osteosclerotic lesions, as observed in our fourth case (Case 4). By contrast, no bone formation occurs in GSD, even after the osteolytic process has stopped.[38] Some patients seem to present an intermediate form, like the case reported by Shivaram et al[29] of severe late-onset CA of the proximal humerus, which continued to grow, complicated 5 years later by disseminated bony involvement, with the development of numerous pathological stress fractures that failed to heal, despite surgery and bisphosphonate treatment. However, this case was nevertheless classified as CA, particularly as follow-up for 15 years showed osteosclerotic conversion for many of the lesions.

4.3.2. Despite more extensive disease in cystic angiomatosis

A second key difference is that CA usually affects several bones in a single patient, whereas areas of bone resorption occur in either a single bone or several contiguous bones in GSD.[38] To our knowledge, only 1 case of multifocal GSD has been reported to date.[41]

4.3.3. Differences in locations

The location of lesions also differs between CA and GSD: skull lesions frequently occur in CA (48%), but rarely in GSD. Conversely, the rest of appendicular skeleton is more frequently involved in CA than GSD patients.[8]

4.3.4. Differences in visceral involvement

Visceral involvement and macrocystic lymphatic malformations are observed more frequently in CA than in GSD,[4 8 42] although about 25% of GSD patients develop chylothorax.[38]

4.3.5. Response to treatment

CA and GSD also appear to differ in terms of their response to several treatments.

Radiation therapy on bone or soft tissue mass has been used in some patients with CA, but with no effect.[3 7 12 16 17 22 23 26] Conversely, several case reports have described the successful use of radiotherapy in GSD, with an overall success rate for the treatment of localized lesions of about 75%.[38] Maximal therapeutic benefit seems to be achieved with the use of 36 to 45 Gray in total, administered in 2-Gray units.[38] Alkaline agents have been tried in 1 CA patient, with no effect.[3]

Interferon alpha treatment has been tested in 2 patients with CA, but was found to be ineffective, whereas this drug has yielded striking improvements in several patients with GSD, when with bisphosphonates[43] or alone.[44 45]

Bisphosphonates successfully stabilized the disease in one of our cases (Case 1) and in several published cases of CA.[30] However, the natural course of this disease is unpredictable, as some patients experience a complete regression of the cystic lesions,[2 32] whereas cystic lesion size and number continue to increase in others. In the most severe cases, CA can result in death even in patients on bisphosphonates, particularly in the presence of chylothorax.[22]

4.4. Pathophysiology of cystic angiomatosis

The pathophysiology of CA and GSD remains poorly understood. Lymphatic vessels are not present in normal bones, but are found in the medullary and cortical regions of bones in patients with GSD[38] and CA. Lymphangiogenesis—the sprouting of new lymphatic vessels from preexisting vessels—occurs in an uncontrolled manner in GSD, but this lymphatic abnormality is considered to be a malformation rather than a tumor.[38] Several prolymphangiogenic factors, either alone or in combination, can stimulate lymphangiogenesis in CA and GSD. Several members of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) family (from A to D) and the angiopoietin family (1 and 2) have already been implicated in this process. A lack of antilymphangiogenic factors (including TGF-beta and interferon-gamma) may also enhance the sprouting of lymphatic vessels in the bones.[38] A positive feedback loop between some bone cells (including mesenchymal cells) and new lymphatic vessels might account for the frequent restriction of lymphangiogenesis to the bone in CA and GSD, although extension to other tissues, such as the pleura, has also been reported in both conditions.

The hypothesis that vascular channel proliferation in the bone marrow affects bone remodeling and causes bone destruction in GSD has been put forward by several different authors.[46–49] Large numbers of pericyte/macrophage-like mononuclear cells with abundant acid phosphatase-positive lysosomal bodies are usually present, and these cells could drive lymphangiogenesis, either directly, or indirectly, by releasing VEGF (A, C–D). However, mature osteoclasts are not always present in areas of bone resorption in GSD, particularly in stable lesions.[38] Thus, although some investigators have observed osteoclasts in osteolytic zones, many others have reported an absence of typical osteoclasts from some areas of bone resorption.[38] Other reports have stressed the lack of evidence for an increase in osteoblast activity in active GSD lesions, in which the disappearing bone is replaced by fibrovascular tissue rather than by newly formed woven repair bone. This lack of osteocyte and osteoblast synthetic activity is puzzling, particularly in the most active lesions of GSD, because the high concentrations of VEGF-A should promote an osteoblastic response by enhancing angiogenesis. These findings suggest that the factors produced by the pathologic lymphatic cells stimulate the differentiation of mesenchymal progenitors along the fibroblastic, rather than osteoblastic lineage in GSD. This appears less likely in CA, because a peripheral sclerotic rim is frequently observed and some lesions may even condense. Such a hypothesis would be consistent with the high levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) reported in the affected bones of some GSD patients[47] (because fibroblasts produce large amounts of IL-6, and this cytokine enhances osteoclast activity), and the normal levels of IL-6 in CA patients.[30]

There is strong evidence to suggest that CA has a genetic basis. For example, 12 cases of diffuse CA have been identified in 4 generations of 1 family. The disease appeared to have an autosomal dominant distribution, with no skipped generations and an equal sex distribution.[15 18] In sporadic cases of CA, mosaicism for a somatic mutation in bone marrow precursor cells has been put forward as an explanation, and similar mutations may also be involved in GSD.[38] Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) from cell lines derived from affected tissues or from the affected tissue itself could be used in exome-sequencing experiments, to detect local genetic changes, either in lymphatic cells or in pericyte/macrophage-like mononuclear cells, which may differ slightly between CA and GSD. However, such an approach could face ethical limitations, because bone biopsy is no longer necessary for the diagnosis of CA, which is instead usually diagnosed on clinical and radiological grounds.[15 18]

5. Conclusion

Our findings for 4 patients, and a review of the clinical and imaging features of CA in previous cases confirmed that CA was a heterogeneous disorder with an unpredictable natural course. New pathophysiological findings are urgently required, particularly as no treatment has yet been shown to be effective at stabilizing cysts or promoting their regression. Further studies should focus on the cellular and molecular aspects of CA, which may be very similar to those of GSD, given the striking similarities between these 2 conditions, despite their different prognoses.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: 18-FDG = 18-fluorodesoxyglucose, CA = cystic angiomatosis, CD = cluster of differentiation, CT scan = computerized tomography scan, DNA = deoxyribonucleic acid, GLA = generalized lymphatic abnormality, GSD = Gorham–Stout disease, IL-6 = interleukin 6, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, NK cells = natural killer cells, PET = Positron emission tomography, SUV = standardized uptake value, TGF-beta = tumor growth factor-beta, VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Levey DS, MacCormack LM, Sartoris DJ, et al. Cystic angiomatosis: case report and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25:287–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boyle WJ. Cystic angiomatosis of bone. A report of three cases and review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1972; 54:626–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seckler SG, Rubin H, Rabinowitz JG. Systemic cystic angiomatosis. Am J Med 1964; 37:976–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. von Knoch F, Grill F, Herneth AM, et al. Skeletal cystic angiomatosis with severe hip joint deformation resembling massive osteolysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2001; 121:48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wallis LA, Asch T, Maisel BW. Diffuse skeletal hemangiomatosis: reports of two cases and review of literature. Am J Med 1964; 37:545–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jacobs JE, Kimmelstiel P. Cystic angiomatosis of the skeletal system. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1953; 35-A:409–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parsons L, Ebbs JH. Generalized angiomatosis presenting the clinical characteristics of storage reticulosis: with some observations on the reticulo-endothelioses. Arch Dis Child 1940; 15:129–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lala S, Mulliken JB, Alomari AI, et al. Gorham–Stout disease and generalized lymphatic anomaly—clinical, radiologic, and histologic differentiation. Skeletal Radiol 2013; 42:917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Joshi M, Phansalkar DS. Simple lymphangioma to generalized lymphatic anomaly: role of imaging in disclosure of a rare and morbid disease. Case Rep Radiol 2015; 2015:6038–6059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang Z, Li K, Yao W, et al. Successful treatment of kaposiform lymphangiomatosis with sirolimus. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62:1291–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clayer M. Skeletal angiomatosis in association with gastro-intestinal angiodysplasia and paraproteinemia: a case report. J Orthop Surg 2002; 10:85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devaney K, Vinh TN, Sweet DE. Skeletal-extraskeletal angiomatosis. A clinicopathological study of fourteen patients and nosologic considerations. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994; 76:878–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ishida T, Dorfman HD, Steiner GC, et al. Cystic angiomatosis of bone with sclerotic changes mimicking osteoblastic metastases. Skeletal Radiol 1994; 23:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malik R, Malik R, Tandon S, et al. Skeletal angiomatosis—rare cause of bone destruction: a case report with review of literature. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2008; 51:515–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pavanello M, Piatelli G, Ravegnani M, et al. Cystic angiomatosis of the craniocervical junction associated with Chiari I malformation: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 2007; 23:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gutierrez RM, Spjut HJ. Skeletal angiomatosis: report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1972; 85:82–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reid AB, Reid IL, Johnson G, et al. Familial diffuse cystic angiomatosis of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; 238:211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Toxey J, Achong DM. Skeletal angiomatosis limited to the hand: radiographic and scintigraphic correlation. J Nucl Med 1991; 32:1912–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris R, Prandoni AG. Generalized primary lymphangiomas of bone: report of case associated with congenital lymphedema of forearm. Ann Intern Med 1950; 33:1302–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Koblenzer PJ, BukowskiIMJ Angiomatosis (hamartomatous hem-lymphangiomatosis). Report of a case with diffuse involvement. Pediatrics 1961; 28:65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shennan T. Histologically non-malignant angioma with numerous metastases. J Pathol 1914; 19:139–154. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gramiak R, Ruiz G, Campeti FL. Cystic angiomatosis of bone. Radiology 1957; 69:347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Soler R, Pombo F, Bargiela A, et al. Diffuse skeletal cystic angiomatosis: MR and CT findings. Eur J Radiol 1996; 22:149–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deveci M, İnan N, Çorapçioğlu F, et al. Gorham-Stout syndrome with chylothorax in a six-year-old boy. Indian J Pediatr 2011; 78:737–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen J, Craig JM. Multiple lymphangiectases of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1955; 37-A:585–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goutoudi PC, Sferopoulos NK, Papavasiliou V, et al. Cystic angiomatosis of bone: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1996; 81:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sferopoulos NK, Anagnostopoulos D, Webb JK. Cystic angiomatosis of bone with massive osteolysis of the cervical spine. Eur Spine J 1998; 7:257–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shivaram GM, Pai RK, Ireland KB, et al. Temporal progression of skeletal cystic angiomatosis. Skeletal Radiol 2007; 36:1199–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marcucci G, Masi L, Carossino AM, et al. Cystic bone angiomatosis: a case report treated with aminobisphosphonates and review of the literature. Calcif Tissue Int 2013; 93:462–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brower AC, Culver JE, Jr, Keats TE. Diffuse cystic angiomatosis of bone. Report of two cases. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 118:456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schajowicz F, Aiello CL, Francone MV, et al. Cystic angiomatosis (hamartous haemolymphagiomatosis) of bone. A clinicopathological study of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1978; 60:100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bergman AG, Rogero GW, Hellman BH, et al. Case report 841. Skeletal cystic angiomatosis. Skeletal Radiol 1994; 23:303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ballina-Garcia FJ, Queiro-Silva MR, Molina-Suarez R, et al. Multiple painful bone cysts in a young man. Ann Rheum Dis 1996; 55:346–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cohen MD, Rougraff B, Faught P. Cystic angiomatosis of bone: MR findings. Pediatr Radiol 1994; 24:256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lomasney LM, Martinez S, Demos TC, et al. Multifocal vascular lesions of bone: imaging characteristics. Skeletal Radiol 1996; 25:255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vanhoenacker FM, De Schepper AM, De Raeve H, et al. Cystic angiomatosis with splenic involvement: unusual MRI findings. Eur Radiol 2003; 13:L35–L39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dellinger MT, Garg N, Olsen BR. Viewpoints on vessels and vanishing bones in Gorham-Stout disease. Bone 2014; 63:47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1955; 37-A:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gorham LW, Wright AW, Shultz HH, et al. Disappearing bones: a rare form of massive osteolysis; report of two cases, one with autopsy findings. Am J Med 1954; 17:674–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tauro B. Multicentric Gorham's disease. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1992; 74:928–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Auge B, Toussirot E, Kantelip B, et al. From polycystic bone angiomatosis to Gorham's disease. Two case-reports and literature review. Rev Rhum Engl Ed 1998; 65:201–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kuriyama DK, McElligott SC, Glaser DW, et al. Treatment of Gorham-Stout disease with zoledronic acid and interferon-α: a case report and literature review. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2010; 32:579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Takahashi A, Ogawa C, Kanazawa T, et al. Remission induced by interferon alfa in a patient with massive osteolysis and extension of lymph-hemangiomatosis: a severe case of Gorham-Stout syndrome. Pediatr Surg 2005; 40:E47–E50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. JKose M, Pekcan S, Dogru D, et al. Gorham-Stout syndrome with chylothorax: successful remission by interferon alpha-2b. Pediatr Pulmonol 2009; 44:613–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dickson GR, Mollan RA, Carr KE. An investigation of vanishing bone disease. Bone 1990; 11:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Devlin RD, Bone HG, III, Roodman GD, et al. Interleukin-6: a potential mediator of the massive osteolysis in patients with Gorham-Stout disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:1893–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pazzaglia UE, Andrini L, Bonato M, et al. Pathology of disappearing bone disease: a case report with immunohistochemical study. Int Orthop 1997; 21:303–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Patel DV. Gorham's disease or massive osteolysis. Clin Med Res 2005; 3:65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]