Abstract

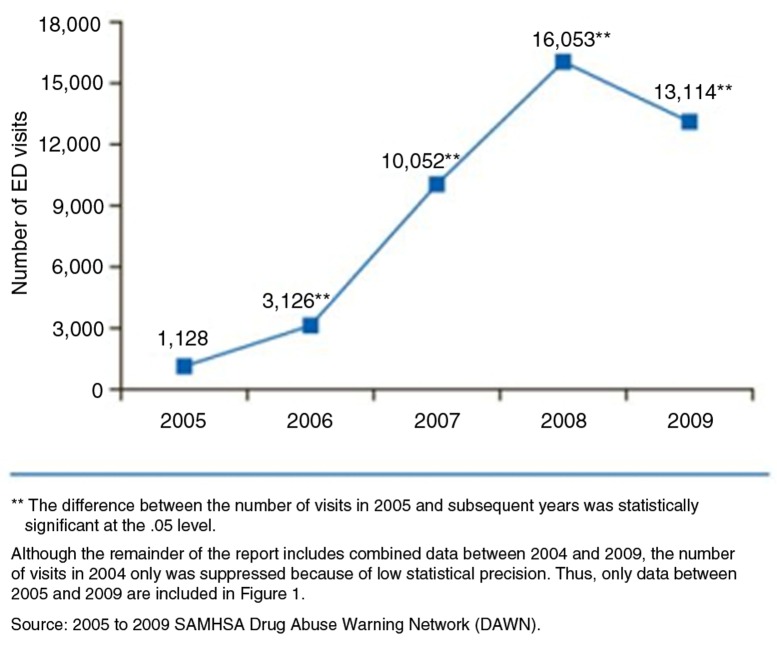

Rhabdomyolysis is defined as a syndrome characterized by muscle necrosis and the release of intracellular muscle constituents into the circulation. We present a case of a 35-year-old male who exercised for 2 h after ingesting energy drink and subsequently presented with rhabdomyolysis. After excluding common and uncommon causes of rhabdomyolysis, we reached the conclusion that the likely cause was the ingestion of energy drink ‘NEON VOLT’ in a setting of mild dehydration. Increasing physical activity and intense exercise is becoming a trend in many countries, due to its many health-related benefits such as prevention of obesity. This renewed focus toward optimal fitness has spawned many supplements that aid in improvement of the performance, muscle growth, and recovery. Energy drinks predominantly contain caffeine that is often combined with other supplements to form what manufacturers have termed an ‘energy blend’. Studies have shown that excessive caffeine intake from energy drinks can cause arrhythmias, hypertension, dehydration, sleeplessness, nervousness, and in rare instances, rhabdomyolysis. As per Drug Abuse Warning Network report, there is a sharp increase in the number of emergency department visits involving energy drinks from 1,128 visits in 2005 to 16,053 and 13,114 visits in 2008 and 2009, respectively. Due to emergence of energy drink abuse as a national health problem, Food and Drug Administration has launched a dietary supplement adverse event reporting system for surveillance of any adverse events linked to these agents.

Keywords: rhabdomyolysis, energy drinks, neon volt, dawn report

Rhabdomyolysis is a syndrome characterized by muscle necrosis and the release of intracellular muscle constituents into the circulation. Creatine kinase (CK) levels are typically markedly elevated to levels of at least 10 times the upper limit of normal and subsequently followed by a rapid decrease. Common causes include substance abuse, medication, trauma, and epileptic seizures. Classical features include myalgia, weakness, and pigmenturia. The severity of illness ranges from asymptomatic elevations in serum muscle enzymes to life-threatening disease associated with extreme enzyme elevations, electrolyte imbalances, and acute kidney injury (1). We present a case of a male who exercised for 2 h after ingesting an energy drink and subsequently developed rhabdomyolysis.

Case presentation

A 35-year-old Hispanic male with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) after experiencing 2 days of dark-colored urine and diffuse muscle aches. The patient had not undergone any physical training in the last 1 year and had progressively gained weight. As such, he decided to start exercising and joined a gym. Two days before his presentation to the ED, patient was instructed by his younger brother to try a new energy drink supplement called ‘NEON VOLT’ prior to beginning his exercise. As per patient, he only ingested two bottles of this drink and started exercising. His regimen included 2 h of weight lifting and running on the treadmill. The following morning, patient experienced diffuse myalgia and noticed dark-colored urine. Patient reported that in the past, he had exercised vigorously for more than 2 h and had never experienced such symptoms. Patient also denied any loss of appetite or poor oral intake. He had no history of urinary frequency/urgency, dysuria, fever/chills, abdominal pain, skin rash, muscle weakness, dizziness, lightheadedness, seizure-like activity, or trauma. He denied any family history of collagen vascular diseases like lupus, glycogen storage diseases, or sickle cell disease. Patient had no history of surgeries in the past. He denied any history of alcohol use but agreed to occasionally smoking marijuana. He was not taking any medications at home including statins or other myotoxic agents. On presentation to ED, his vitals included temperature of 36.2°C, blood pressure of 123/87 mmHg, heart rate of 71/min, respiratory rate of 22/min, and oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. Physical examination revealed diffuse muscle tenderness and dry oral mucosa. Cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal, and skin examinations did not reveal any significant abnormalities.

Laboratory studies revealed CK of 73,739 IU/L (normal 38–174 IU/L) on admission which increased to 100,290 IU/L the next day. Basal metabolic panel showed serum sodium of 140 mEq/L, potassium of 4.0 mEq/L, chloride of 104 mEq/L, bicarbonate of 27 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen of 14 mEq/L, and creatinine of 0.89 mEq/L. Liver function tests revealed an elevated aspartate transaminase level of 581 U/L (normal 0–40 U/L) and alanine transaminase level of 229 U/L (normal 0–41 U/L), which continued to trend down during the hospitalization. Blood alcohol level was zero and urine toxicology was positive for only marijuana. Tests for hepatitis A, B, C viruses and human immunodeficiency virus infection (HIV) were negative. Complete blood count revealed white blood cell count (WBC) of 9.4/mL, hemoglobin/hematocrit of 13.3 g/dL/40.5%, respectively. Urinalysis showed large blood but very few red blood cells—a finding consistent with myoglobinuria.

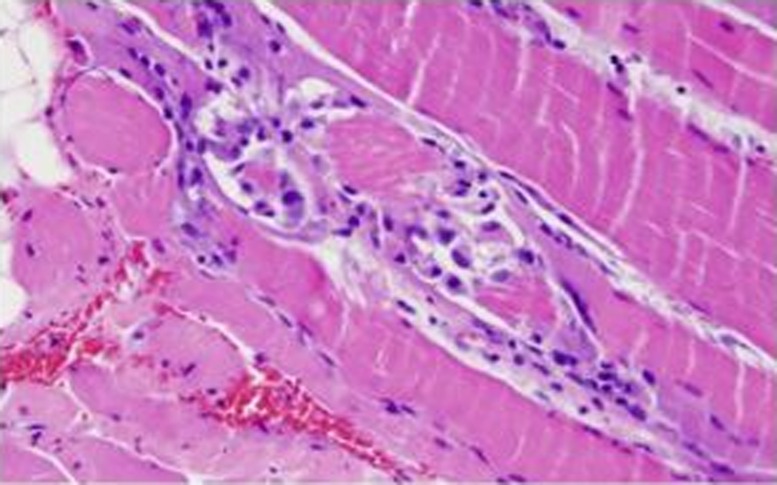

The patient was started on intravenous normal saline at a rate of 250 cc/h. With hydration, his CK levels decreased and his symptoms improved. Throughout his hospital course, the patient's renal function remained normal. As no definitive cause of rhabdomyolysis was discovered in this patient, an extensive workup was initiated including aldolase, anti-nuclear antibody, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, anti-double-strand DNA, Anti-Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen A (anti-SSA) and Anti-Sjögren's-syndrome-related antigen B (SSB) antibodies, anti-ribonucleoprotein, and anti-smooth muscle; and myositis-associated and myositis-specific antibodies including anti-Jo1, all of which were negative. Patient also received a muscle biopsy that revealed inflammation and muscle necrosis without any evidence of perifascicular atrophy or fibrosis or glycogen deposition (Fig. 1), thus ruling out inflammatory myopathies, collagen vascular diseases, and glycogen storage diseases as a cause of his rhabdomyolysis. At this time, the contents of the energy drink ‘NEON VOLT’ were reviewed (Fig. 2), and it was seen to have excessive quantities of caffeine (five times as much as a regular cup of coffee), taurine, B-alanine, which could possibly be myotoxic. Thus, it was concluded that the cause of the patient's rhabdomyolysis was the energy drink coupled with mild dehydration. After 3 days of adequate fluid resuscitation, patient was completely asymptomatic with CK level of 7,277 IU/L on discharge. On discharge, patient was also instructed to avoid consuming energy drinks and was educated regarding the harmful effects of these energy supplements. On regular clinical visit 2 weeks later, patient was still asymptomatic and his CK levels had dropped to 100 IU/L.

Fig. 1.

Muscle biopsy showing inflammation and neutrophilic infiltration with muscle necrosis consistent with rhabdomyolysis. Courtesy of Department of Pathology, Saint Francis Medical Center.

Fig. 2.

Figure depicting the ingredients of energy drink ‘NEON VOLT’.

Discussion

Increasing physical activity and intense exercise is becoming a common trend in many countries due to its well-recognized health-related benefits particularly in treatment and prevention of obesity (1). With this focus toward improved fitness and self-image, many new supplements are arriving in the market to improve muscular performance, growth, and recovery. The initial goal of these sports drinks was to provide electrolytes repletion and carbohydrates replacement. However, in due time, energy beverages (EBs) containing stimulants and additives began to appear in most gyms and grocery stores and are being used increasingly by the ‘weekend warriors’ and those seeking an edge in an endurance event (1). Consumption of EBs is most common among people between age groups of 11 and 35 years, and 24–57% of this population has been noted to drink such EBs daily. Marketing of these energy drinks often targets people of aforementioned age groups, suggesting benefits such as increased energy and stamina, weight loss, and enhanced physical and/or mental performance (2). The popularity of these drinks has increased markedly in recent years, with energy drink sales increasing by 240% from 2004 to 2009.

Energy drinks predominantly contain caffeine that is often combined with taurine, beta alanine, L-citrulline, B vitamins, ginseng, and ginkgo biloba to form what manufacturers have called an ‘energy blend’. Hundreds of different brands are now marketed with caffeine content ranging from a modest 50 mg to an alarming 505 mg per can or bottle. This is equivalent to 5–10 times the amount of caffeine present in a regular 5 oz cup of coffee. Our patient consumed energy drink ‘NEON VOLT’ that contains the above-mentioned ingredients except gingko biloba (Fig. 2). When such high doses of caffeine are combined with these other substances, the subsequent effects cannot always be predicted. Studies have shown that excessive caffeine intake from energy drinks can cause arrhythmias, hypertension, dehydration, sleeplessness, nervousness, and in rare instances, rhabdomyolysis. In our literature search, only one case report of rhabdomyolysis caused by caffeinated beverages was found (3). Additional complications can arise depending on the individual's overall health status (e.g., cardiac conditions, diabetes and anxiety disorders) and other drugs or medications that patients may be taking (e.g., medications for attention deficit disorder). Persistent use over time can cause dependence as well as withdrawal symptoms (4). Of note, caffeine appears on the list of substances banned by the International Olympic Committee. Most of the other compounds have not been studied extensively to determine their adverse effects. But ginseng and gingko biloba have been shown to cause hypotension, edema, palpitations, vertigo, headache, mania, euphoria, and hepatotoxicity (1).

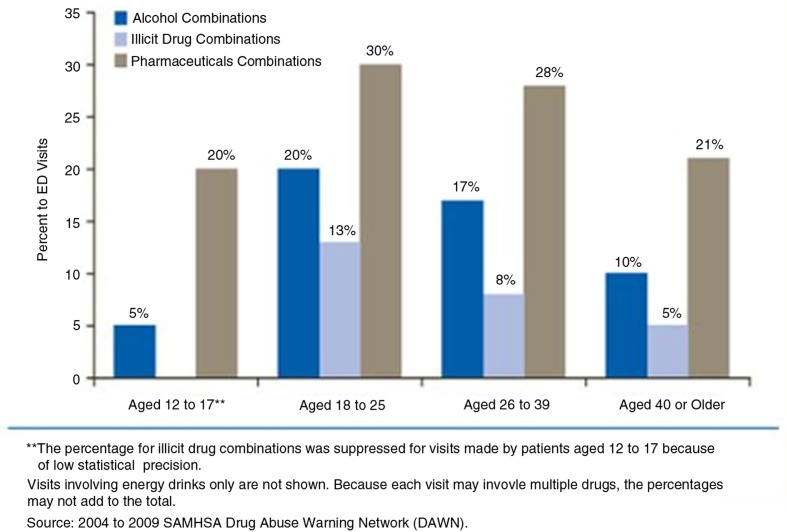

As per Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) report published in 2011, there is a sharp increase in the number of ED visits involving energy drinks from 1,128 visits in 2005 to 16,053 and 13,114 visits in 2008 and 2009, respectively (Fig. 3). Data also indicate that the majority of ED visits involving energy drinks were made by patients aged 18–39 years. Out of these ED visits, 56% were secondary to energy drink consumption alone; about 27% visits were due to energy drinks in combination with pharmaceuticals, 16% in combinations with alcohol and, 10% in combinations with illicit drugs (Fig. 4). Most of the patients who presented to the ED with energy drinks overdose denied consumption of more than two to three cans or bottles. Associations have been established between energy drink consumption and problematic behaviors such as marijuana use, sexual risk-taking, fighting, smoking, drinking and prescription drug misuse in the college students. Individuals incorrectly believe that consumption of caffeine can ‘undo’ the effects of alcohol or illicit drug use. As a result of this belief, co-ingestion of these EBs with alcohol or illicit drugs is very common among younger population (5).

Fig. 3.

Energy drink-related ED visits by year: 2005–2009. Obtained from Ref. [5].

Fig. 4.

Percentage of ED Visits involving Energy Drink Combinations, by age group: 2004–2009. Obtained from Ref. [5].

Currently, no energy drinks are banned in the United States. This is in contrast to many countries where these drinks have been banned and companies are not allowed to outline the performance effects of their products. This absence of oversight has resulted in aggressive marketing of these beverages thus openly promoting psychoactive, performance enhancing, and stimulatory drugs (1). In 2009, scientists and physicians signed a petition that was delivered to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) asking for more regulation of increasingly popular EBs. On January 17, 2014, FDA launched a dietary supplement adverse event reporting system for surveillance of any adverse events linked to these agents (6). This reporting system is available to both patients and physicians to report any adverse effects of such dietary supplements.

In our particular case, we ruled out the common and uncommon causes of rhabdomyolysis in this young, otherwise healthy individual. By excluding the other causes, we arrived at the conclusion that the cause of rhabdomyolysis in this patient was probably secondary to the ingestion of energy drinks in a setting of mild dehydration. Although this patient admitted to having ingested only two bottles of the energy drink ‘NEON VOLT’, it has been noted in the prior studies that most of these young individuals deny abusing such drinks (7). As such, it may be impossible to determine the quantity of ‘NEON VOLT’ that he truly consumed. In summary, after careful review of the literature, it can no longer be ignored that the consumption of energy drinks is a rising public health problem in the United States. It is our responsibility as physicians to inform the patients about the potential harmful effects of energy drinks and raise awareness regarding this FDA dietary supplement reporting system.

Conflict of interest and funding

No funding was provided during the development or completion of this manuscript, and no known or suspected conflict of interest exists between the authors and the enclosed subject matter.

References

- 1.Gabow PA, Kaehny WD, Kelleher SP. The spectrum of rhabdomyolysis. Medicine. 1982;61(3):141. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Higgins JP, Tuttle TD, Higgins CL. Energy beverages: Content and safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(11):1033–41. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiang WF, Liao MT, Cheng CJ, Lin SH. Rhabdomyolysis induced by excessive coffee drinking. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2014;33:878–81. doi: 10.1177/0960327113510536. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0960327113510536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seifert SM, Schaechter JL, Hershorin ER, Lipshultz SE. Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):511–28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The DAWN Report: emergency department visits involving energy drinks. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thombs DL, O'Mara RJ, Tsukamoto M, Rossheim ME, Weiler RM, Merves ML, et al. Event-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Addict Behav. 2010;35(4):325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernstein GA, Carroll ME, Thuras PD, Cosgrove KP, Roth ME. Caffeine dependence in teenagers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;66(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]