Case

A 22-year old female presented in 2008 at the outpatients clinic of our department for evaluation of an extended pelvic osteolysis, being diagnosed accidentally after a fall fifteen days before administration. The patient reported inability to weight bearing and intense pain at her left hip. On clinical examination, edema of the proximal femur was obvious, while the patient could not perform any passive or active movement.

No chronic diseases, weight loss or previous injury at the pelvis were documented at the patient’s past medical history. Her blood tests were within normal range, as well as inflammatory markers, while kidney and liver function was not disturbed. Tests regarding thyroid, parathyroid and steroid hormones were within normal values, while insufficiency of vitamin D was as 11.9 ng/ml. Also no signs of autoimmune disease were detected. The urine calcium test was high as 323.82 mg/24hr (normal range 50-250 mg/24hr) and total urine proteins were 0.03 g/24hr (normal range 0.04-0.15 g/24hr). Markers of bone metabolism where within normal range.

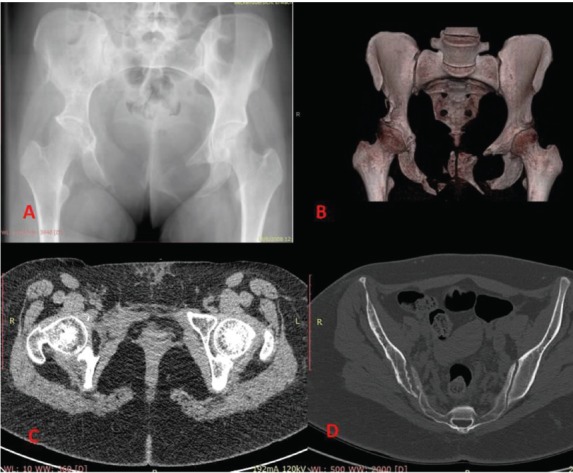

Simple anteroposterior x-ray of the pelvis (Figure 1A) showed extensive bilateral osteolysis of the pelvic ring. Lymphangiography with Technetium 99 showed increased uptake on right inguinal and popliteal lymph nodes. Absence of the middle and posterior wall of the right acetabulum was diagnosed by Computed Tomography (CT) scan (Figure 1B) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) (Figure 1C), while arthritic changes of the right sacroiliac joint were revealed (Figure 1D). Biopsy under CT scan was performed and diagnosis of Gorham Stout disease was suggested, due to intramedullary destruction of bone architecture, as bone tissue was replaced by lymphatic tissue and osteoblastic activity was absent. Neoangiogenesis was also aggressive and extended widely in the bone marrow.

Figure 1.

A) Anteroposterior radiograph of the pelvis. Bilateral osteolysis of the pelvic ring, remnants of the pubis, protrusion of the right femoral head are viewed. B) CT scan with 3D reconstruction. Absence of the anterior and middle wall is presented. C) T2 weighted image on MRI scan. D) T1 weighted image on CT scan. Osteoarthritis of the right sacroiliac joint is revealed.

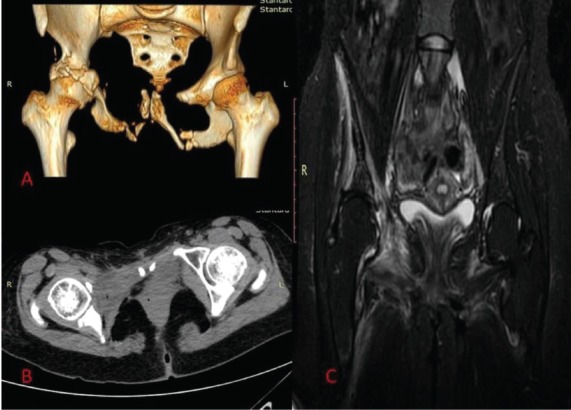

The patient went under transcutaneous radiotherapy of the pelvis, receiving a total dose of 45 Gy, one year after the onset of the symptoms. Osteolysis was progressive and biphosphonates were administered. She had a yearly follow up with CT and MRI scan. On last examination (Figure 2A-C) osteolytic destruction of the posterior wall and the roof of the right acetabulum, edema of the right hip flexors and progressive arthritis of the involved right hip were demonstrated. The patient complained of complete inability to weight bearing on her right hip. The patient denied amputation of the extremity and nowadays she continues her daily activities by the use of crutches.

Figure 2.

A) CT scan with 3D reconstruction 7 years after diagnosis. Note the extended osteolysis of the right acetabulum. B) CT scan with T1 weighted images. The right femoral head is completely uncovered. C) Edema of the right hip flexors was revealed in MRI scan.

Comments

The Gorham-Stout disease is also known as massive osteolysis syndrome or vanishing bone syndrome. Gorham LW and Stout AP[1] were the first to present a large series of 24 cases and to separate the disease from the general terminology of idiopathic osteolysis, which was first described by Jackson JBS in 1838. According to Hardegger‘s classification[2], massive osteolysis is one of the five types of idiopathic osteolysis. It has no predilection in gender or race. It may occur at any age, but it is diagnosed more often in adolescents and children. Bones are affected in a monocentric manner, though there are reports of continuity to adjacent bone structures. Any bone can be affected with mandible, ribs, femur, pelvis, humerus and scapula mostly involved.

Aetiopathogenesis is unknown. Hereditary pattern is unclear. Massive and progressive osteolysis is due to hyperactivity of the osteoclasts, in which Interleukine 6 might play an important role as a mediator to the procedure, mostly at early stages of the disease. Many authors noted an increase in expression of hydrolytic enzymes such as acid phosphatase in perivascular mononuclear cells. Hyperaemia, local changes of pH and mechanical causes might inhibit osteolysis according to Gorham and Stout. Lymphatic and neovascular tissue extensively replace bone tissue, therefore Hagendoorn[3] suggested that the signaling pathway of the PDGFR-b (receptor of the lymphangiogenic growth factor: Platelet Derived Growth Factor BB) could play some role in pathogenesis, since characteristics of a disturbed lymphangiogenesis are usually observed.

Clinical presentation can vary from an asymptomatic patient to a patient with acute or progressive pain in the affected area. A pathological fracture after a fall or under minimal charge is usually the first sign of the disease. Pain and edema at the affected area are common, while functional disability of the involved extremity may occur when osteolysis progresses. Weakness and muscular atrophy may progress. In cases of thoracic cage involvement, chylothorax due to lymphangectasia, increases morbidity and mortality. Meningitis and paraplegia are rarely reported as neurological symptoms.

On simple radiographs progressive destruction in early stages begins at the medullary and subcortical structures, without periosteal reaction. Osteoporotic changes become progressively extensive and at later stages cortical resorption becomes visible. Osteolysis[4] is concentric in long bones. Pathological fractures are common, bone is replaced by fibrous tissue and the main characteristic is the absence of new bone formation. Scintigraphy is not diagnostic for the disease, although scintigraphic lymphangiography might show increased uptake on local lymph nodes, as it was in our case. CT and MRI scan, especially with the use of 3D reconstruction, provide an excellent tool in displaying bone and soft tissue structures. Low signal intensity on T1 weighted images and high on T2 weighted images is the usual result. In some cases, soft tissue show intense uptake, but usually results vary in literature.

Needle biopsy under CT guidance is considered fundamental for the diagnosis of Gorham-Stout disease. The main histological finding is the replacement of bone tissue from vascular and lymphatic tissue, separate or simultaneously in appearance. No cellular atypia is present and osteoblastic response is minimal or absent. The bony replacement procedure is divided in two stages. It starts with vascular proliferation and continues with substitution by fibrous tissue.

Current laboratory blood and urine tests do not provide enough specification in the diagnosis of massive bone osteolysis. Blood investigation, inflammatory markers, screening tests for endocrine disorders, serum calcium, acid and alkaline phosphatase are within normal range, in most of the reported cases in literature. There are only sporadic reports involving increase of serum alkaline phosphate, eosinophils and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Nowadays much discussion focuses on the special markers of the lymphatic tissue. Lymphatic[5] vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor-1 (LYVE-1), podoplanin, Prox1 and VEGF-receptor-3 (VEGFR-3) are specific for lymphatic endothelial cells. The simultaneous presence of LYVE-1 and expression of CD-31 (platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule) in the proliferating lymphatic endothelial cells in Gorham-Stout syndrome might become the key point for early diagnosis and future treatment of the disease.

Treatment of massive osteolysis is divided on two parts. Firstly pharmacological therapy should focus on decreasing the rapid osteolysis, in order to control its evolution and avoid extended comorbidities. Biphosphonates are used due to their anti-osteoclastic properties, as a monotherapy or in combination with periodic use of interferon α2b (INF-α2b). Vitamin D supplements and steroids show little effectiveness. Thalidomide or blockers of angiogenetic growth factors receptors have also been used, with little success. Radiotherapy with an average total dose of 45 Gy appears to be effective in controlling the disease, though possible side effects especially in developmental ages, makes patients considerable against its use. Secondly, stabilization and reconstruction of the affected bones are critical for the life quality of the patient. Open reduction and internal fixation with plates or intramedullary nails, when long bones are affected, prostheses, with the simultaneous use of bone grafts have been used in most cases. Amputation is an option in cases of irreparable bone destruction. When chylothorax occurs, thoracic duct ligation, pleurodesis, and chest drainage should be used. In general, surgical treatment should follow the initial pharmacological effort to control osteolysis.

Conclusively, Gorham-Stout disease is a rare pathological entity. Aetiology is unknown, while symptoms and clinical tests are not specific for its diagnosis. Each case is treated individually, taking into concern its specific characteristics. New therapeutic approaches and clinical studies are needed for improvement of current treatment options.

Footnotes

Edited by: P. Makras

Questions

1. Gorham-Stout disease refers to:

A. Juvenile osteoporosis

B. Osteonecrosis of the jaw

C. Parodic metatraumatic osteolysis

D. Massive idiopathic osteolysis

Critique

Gorham-Stout disease refers to massive idiopathic osteolysis. Gorham and Stout individualized massive osteolysis from the general term idiopathic osteolysis, presenting a series of 24 cases at 1955. According to Hardegeer’s classification system, massive osteolysis is one of the five subtypes of idiopathic osteolysis. The correct answer is D.

2. Main histological characteristic of massive idiopathic osteolysis is:

A. Hyperactivity of osteoblasts.

B. Bone tissue replacement by lymphatic and/or vascular tissue.

C. Cellular atypia.

D. Calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition.

Critique

Lympangiogenesis or neoangiogenesis inside bone structures and extended replacement of the bone tissue by lymphatic or/and vascular tissue is the main characteristic of Gorham-stout disease. At later stages progressive fibrosis completes extensive osteolysis. Osteoblastic activity is minimal or absent. Cellular atypia and calcium pyrophosphate crystals are not connected with massive osteolysis.

The correct answer is B.

3. Final diagnosis of Gorham-Stout disease is based on:

A. Biopsy under CT guidance.

B. Increased levels of serum calcium and alkaline phosphate.

C. 3D MRI

D. All of the above.

Critique

Haematological and biochemical tests are usually normal in massive idiopathic osteolysis. There is no correlation between endocrinological disorders and Gorham-Stout disease. Up to now there are no specific laboratory tests for early or late diagnosis. 3D MRI is fundamental for the diagnosis of bone and marrow destruction, as well as other adjacent soft tissue changes. Histological findings after guided biopsy are the manifestation of diagnosis. Extensive lymphatic with/or neovascular tissue within bone structures, replacement by fibrous tissue at later stages, absence of osteoclastic activity are common in most reported cases. The correct answer is A.

4. Most widely conservative treatment for Gorham-Stout

disease is:

A. Corticosteroids and Non steroid anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs)

B. Teriparatide and vitamin D

C. Corticosteroids and methotrexate

D. Biphosphonates combined with INF-α2b, followed by radiotherapy.

Critique

Biphosphonates, having anti-osteoclastic and pro-osteogenic properties, are the first line pharmacological agents in order to minimize osteolytic destruction. Successful treatment depends on the osteoclastic activity, which rarely becomes clear. Interferon is useful since its antiangiogenic properties decreases vessel proliferation. The use of radiotherapy in average total dose of 45 Gy, though with considerable side effects, may prevent disease progression effectively. Corticosteroids and NSAID are used as supplementary agents. Teriparatide is not a treatment of choice nowadays.

The correct answer is D.

References

- 1.Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone): its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1955;37-A:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardegger F, Simpson LA, Segmueller G. The syndrome of idiopathic osteolysis. Classification, review, and case report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67-B:88–93. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.67B1.3968152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagendoorn J, Padera TP, Yock TI, Nielsen GP, Di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Delaney TF, Gaissert HA, Pearce J, Rosenberg AE, Jain RK, Ebb DH. Platelet-derived growth factor receptorbeta in Gorham’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:693–697. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moller G, Priemel M, Amling M, et al. The Gorham-Stout syndrome (Gorham’s massive osteolysis). A report of six cases with histopathological findings. The Journal of bone and joint surgery British volume. 1999;81(3):501–506. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b3.9468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagendoorn J, Yock TI, Borel Rinkes IH, Padera TP, Ebb DH. Novel molecular pathways in Gorham disease: Implications for Treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(3):401–406. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]