Abstract

Aims

(1) To compare alcohol‐attributed disease burden in four Nordic countries 1990–2013, by overall disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) and separated by premature mortality [years of life lost (YLL)] and health loss to non‐fatal conditions [years lived with disability (YLD)]; (2) to examine whether changes in alcohol consumption informs alcohol‐attributed disease burden; and (3) to compare the distribution of disease burden separated by causes.

Design

A comparative risk assessment approach.

Setting

Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland.

Participants

Male and female populations of each country.

Measurements

Age‐standardized DALYs, YLLs and YLDs per 100 000 with 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs).

Findings

In Finland, with the highest burden over the study period, overall alcohol‐attributed DALYs were 1616 per 100 000 in 2013, while in Norway, with the lowest burden, corresponding estimates were 634. DALYs in Denmark were 1246 and in Sweden 788. In Denmark and Finland, changes in consumption generally corresponded to changes in disease burden, but not to the same extent in Sweden and Norway. All countries had a similar disease pattern and the majority of DALYs were due to YLLs (62–76%), mainly from alcohol use disorder, cirrhosis, transport injuries, self‐harm and violence. YLDs from alcohol use disorder accounted for 41% and 49% of DALYs in Denmark and Finland compared to 63 and 64% in Norway and Sweden 2013, respectively.

Conclusions

Finland and Denmark has a higher alcohol‐attributed disease burden than Sweden and Norway in the period 1990–2013. Changes in consumption levels in general corresponded to changes in harm in Finland and Denmark, but not in Sweden and Norway for some years. All countries followed a similar pattern. The majority of disability‐adjusted life years were due to premature mortality. Alcohol use disorder by non‐fatal conditions accounted for a higher proportion of disability‐adjusted life years in Norway and Sweden, compared with Finland and Denmark.

Keywords: Alcohol, comparative, comparative risk assessment, consumption, disease burden, Nordic countries

Introduction

Alcohol consumption is an important risk factor for mortality and morbidity 1, 2 and as part of public health monitoring, countries and regions often assess patterns of alcohol consumption and alcohol‐related harm 3. Comparative studies play an important role in determining how well countries measure up against each other and can help to understand determinants influencing drinking behaviour and adverse health effects 4. Until now, alcohol‐related mortality, and in particular cirrhosis mortality, has been used as the standard indicator due to its universal coverage and coding rules set up by the World Health Organization (WHO) 5. However, alcohol‐related death does not estimate disease burden; that is, morbidity due to non‐fatal conditions such as alcohol use disorder and injuries is not captured.

An increasingly used measure to estimate overall disease burden in the population, combining premature death or years of life lost (YLL) and years lived with disability (YLD), is disability‐adjusted life years (DALY) 6. DALY as a metric was developed in the 1990s 7 within the global burden of disease study (GBD). Results from the latest iteration of the GBD study were published in 2015, the so‐called GBD 2013 8, 9. The analysis of risk factors for burden of disease have identified approximately 30 conditions attributed to alcohol which have been incorporated into the GBD 2013 1. The GBD estimates thus allow for a more comprehensive assessment of alcohol‐attributed disease burden than previously.

In the Nordic countries there has been a strong interest to follow and compare consumption and alcohol‐related harm using cause of death data. Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland share important population, geographical and welfare characteristics, and alcohol consumption is deeply rooted in the culture of these countries 10. However, there are also notable differences with respect to alcohol policies and overall alcohol consumption over time. Sweden and Norway stand out historically as having restrictive alcohol policies, while Finland, although more lately, and especially Denmark, have a more liberal approach. As a consequence, the consumption levels in Denmark and Finland are higher than in Sweden and Norway, which also has been reflected in countrywise mortality rates from alcohol‐related causes such as liver cirrhosis and injuries 11.

At the same time, there is a geographical gradient in the effect of alcohol on mortality that in general is stronger in northern Europe compared to southern and central Europe 12. This supports the importance of drinking patterns. The Nordic countries have fairly similar drinking cultures 13, but report differences in levels of consumption and alcohol‐related mortality. Important questions are thus how temporal and geographical patterns of alcohol‐related harm are distributed across the Nordic countries when including non‐fatal conditions, and also whether changes in harm over time reflects level of consumption when using the broader indicator of DALY. To quantify and compare overall harm and to identify key areas in which most of the harm occurs is crucial for laying a basis for specific policy measures, both in the field of prevention and treatment 13.

In this study, we used the results from the Global Burden of Disease and Injuries and Risk Factors 2013 study to present new comparative estimates on the alcohol‐attributed disease burden in the Nordic countries between 1990 and 2013. More specifically we aimed to:

Compare the alcohol‐attributed disease burden by overall DALYs, premature mortality (YLLs) and health loss from non‐fatal conditions (YLDs);

Examine whether changes in alcohol consumption informs alcohol‐attributed disease burden; and

Compare the distribution of alcohol‐attributed disease burden separated by causes.

Methods

DALYs, YLLs and YLDs

The GBD is currently the leading system to monitor overall disease burden as well as the contribution of risk factors. The latest iteration GBD 2013, which has been described in detail elsewhere 1, 8, 9, 14, has expanded in scope and comprises estimates of 306 diseases and injuries and 2337 sequelae (non‐fatal health consequences of disease and injuries) for men and women in 20 age groups, and uses DALY as measure of population health. DALYs assess years of healthy life lost by different causes and are calculated by adding together YLLs and YLDs.

The YLLs are based on 240 causes of death and are calculated by multiplying the number of deaths for each cause in each age group by a reference life expectancy at that age 8, 9. The reference life expectancy at birth is based on the lowest observed death rates for each age group across countries in 2013 15. The cause of death estimates are based on vital registration, i.e. the cause of death registers in the Nordic countries.

The YLDs are based on two components, the prevalence of each of the 2337 sequelae, i.e. non‐fatal health consequences of disease and injuries, and the disability weights 14. Disability weights are based on the general public's assessment of the severity of health loss associated with a health state, and is a number between zero (perfect health) and one (death) 16, 17. For example, mild alcohol use disorder has a disability weight of 0.235 and severe alcohol use disorder of 0.570. YLDs are calculated by multiplying the prevalence of each sequelae by its disability weight, and the number of YLDs for a specific disease or injury is the sum of the YLD from each sequelae arising from that cause, resulting in a total of 301 diseases and injuries 14. To obtain prevalence estimates for each sequel, available data on prevalence, incidence, remission, duration and excess mortality have been identified through a systematic search of published and unpublished sources 18. A modelling tool called DisMod‐MR 2.0 (Disease Modeling–Metaregression) was used to generate the prevalence estimates from these data 14.

Alcohol as a risk factor in GBD

According to GBD 2013 estimates, alcohol was ranked to be the sixth leading risk factor to overall disease burden globally 1. The contribution of alcohol is estimated using a comparative risk assessment approach in which observed health outcomes are compared to those that would have been observed with a counterfactual set of exposure where no one is exposed 19. Calculations of the contribution of alcohol include several steps, as follows.

Estimating the relative risk of alcohol for a given mortality or morbidity outcome; Alcohol has been causally related to approximately 30 diseases and injuries including harm to others, and relative risks in these exposure‐outcome associations are estimated on the basis of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, usually giving a continuous risk function over average daily consumption amounts 20.

Estimating the distribution of alcohol exposure in countries by age and sex; first, the average all‐age consumption per capita is estimated using Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and WHO Global Information System on Alcohol and Health data. This all‐age consumption estimate incorporates registered and unregistered consumption, se details in appendix of sources 1, 21, and is considered more reliable than survey data on consumption recall. Secondly, these all‐age consumption estimates are split into 5‐year age groups based on the consumption by age and sex estimated in DisMod‐MR 2.0 using survey recall data, by taking the proportions of consumption in each age–sex group and applying those proportions to 80% total consumption to account for spillage, wastage and breakage; see details in the Supporting information of source 1. Other exposure data are also estimated using DisMod‐MR 2.0: the proportions of the population that are drinkers, binge drinkers, former drinkers or never‐drinkers (abstainers); and the frequency of binge events among binge drinkers 1, 21.

The contribution of alcohol to disease burden is estimated by comparing the population risk of diseases or injuries under the current exposure distribution, to a theoretical counterfactual distribution, where no one is exposed, known as the population attributable fraction. Thus, for alcohol this is achieved by using the disease‐specific relative risks (i.e. the risk of disease at different levels of alcohol consumption versus zero exposure to alcohol, i.e. never‐drinkers or abstainers) from the meta‐analyses described above and the estimated distribution of alcohol consumption in the population described above. The general approach for the calculation of this attributable fraction and some alcohol‐specific methods are described elsewhere, the Supporting information in source 1. This fraction is then applied to the overall disease specific burden (DALYs, YLLs and YLDs) to gain the alcohol‐attributable disease specific burden.

Analytical strategy

We used the results from GBD 2013 to present the age‐standardized rates of DALYs, YLLs and YLDs per 100 000, with 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) between 1990 and 2013 at a 5‐year interval. Age‐standardized rates adjust for total population and changes in age‐specific population sizes over time, and allow comparison of alcohol‐attributed health outcomes across countries. The following specific causes were included: alcohol use disorder, self‐harm and violence, transport injuries, unintentional injuries, cirrhosis, neoplasms, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, epilepsy, pancreatitis, lower respiratory infections and tuberculosis. Some of these are based on more detailed diagnoses such as, for example, type of transport injury or neoplasm (see Supporting information, Table S1). ICD codes for all included cases are available in the Supporting information, Table S3 of source 15. Results on consumption levels as well as estimates of alcohol‐attributed disease burden were extracted from the IHME database.

Results

Alcohol‐attributed disease burden (by overall DALYs, YLLs and YLDs) and population drinking

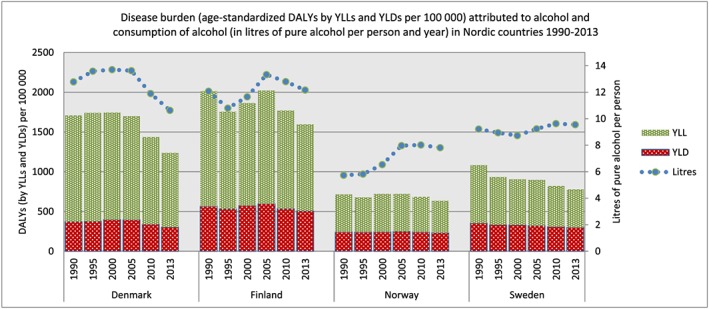

Figure 1 shows the alcohol‐attributed disease burden by overall DALYs, YLLs and YLDs per 100 000 and levels of population drinking between 1990 and 2013 in the four countries. In Finland, having the highest alcohol‐attributed disease burden over the study period, overall DALYs decreased from 2060 (UI = 1790–2394) in 1990 to 1616 (UI = 1391–1859) in 2013, with a peak in 2005 with 2053 DALYs (95% UI = 1807–2294). Norway had the lowest burden and DALYs decreased from 715 (UI = 545–897) in 1990 to 634 (UI = 521–765) in 2013, with a peak in 2000 with 721 DALYs (95% UI = 577–872). Denmark's alcohol‐attributed disease burden (1729: UI = 1463–2037 in 1990 and 1246: UI = 1053–1433 in 2013) was closer to the levels in Finland, while in Sweden (1101: UI = 918–1300 in 1990 and 788: UI = 655–938 in 2013) it was closer to Norway (see Supporting information, Table S2 for details).

Figure 1.

Disease burden [age‐standardized disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) by years of life lost (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs) per 100 000] attributed to alcohol and consumption of alcohol (in litres of pure alcohol per person and year) in Nordic countries 1990–2013

The majority of the disease burden attributed to alcohol was due to premature mortality (YLLs) in all countries. In 1990 and 2013 overall YLLs accounted for approximately 73 and 69% of all DALYs in Finland, 78 and 76% in Denmark, 66 and 63% in Norway and 68 and 62% in Sweden (not shown).

In Denmark and Finland changes in overall alcohol‐attributed disease burden generally responded to changes in population drinking over the years. In Sweden and Norway, the consumption levels increased between 2000 and 2010, although not followed by a similar increase in disease burden.

Alcohol‐attributed disease burden (DALYs) distributed by causes

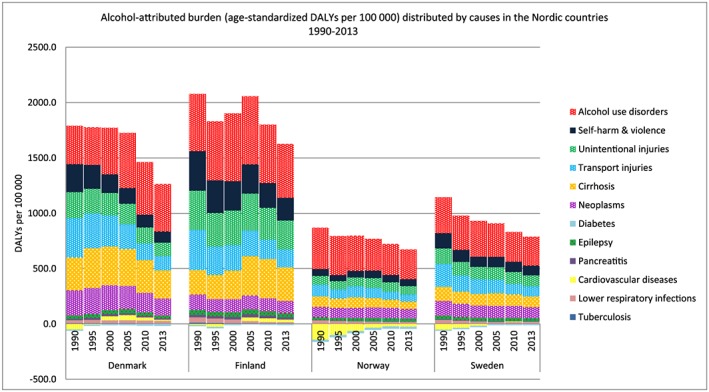

Figure 2 shows the alcohol‐attributed disease burden (age‐standardized DALYs per 100 000) distributed by causes over time in all countries. Even if Finland and Denmark had higher levels of alcohol‐attributed health problems, all countries followed a similar pattern, e.g. alcohol use disorder was the leading cause and accounted together with cirrhosis, transport and unintentional injuries, self‐harm and violence and neoplasms for the majority of the alcohol‐attributed disease burden as measured by DALYs.

Figure 2.

Alcohol‐attributed burden [age‐standardized disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100 000] distributed by causes in the Nordic countries 1990–2013

There are some discrepancies within and between countries over time. In Finland DALYs of cirrhosis, alcohol use disorders and injuries fluctuated over the years. Alcohol use disorders and cirrhosis were highest in 2005 with 617 DALYs (95% UI = 444–757) and 355 DALYs (95% UI = 317–386). At the same time, the burden of self‐harm and violence decreased from 1990 to 2013 by 358 DALYs (95% UI = 302–408) to 205 DALYs (95% UI = 174–269) and transport injuries from 364 DALYs (95% UI = 318–415) to 162 DALYs (95% UI = 138–189). The relative contribution of neoplasms to DALYs was not as prominent in Finland as in the other three countries.

Denmark and Sweden had a similar pattern as Finland for alcohol use disorder, being highest in Denmark in 2005 (498 DALYs, 95% UI = 352–601) and in 2000 in Sweden (324 DALYs, 95% UI = 250–414). In contrast, even if cirrhosis also made an important contribution to DALYs in Denmark, instead it decreased gradually between 1995 and 2013 (from 358 DALYs, 95% UI = 318–391 to 254 DALYs, 95% UI = 213–290), as did self‐harm and violence, transport injuries and neoplasms. In Sweden and Norway, the burden of transport injuries, neoplasms, unintentional injuries, self‐harm and violence and cirrhosis more or less shared the second place after alcohol use disorder from 2000 onwards, and all decreased slightly over time.

Alcohol‐attributed disease burden (by YLLs and YLDs) distributed by causes

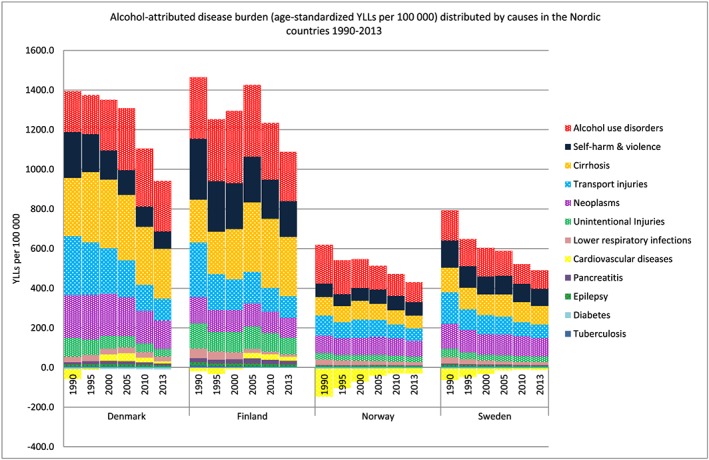

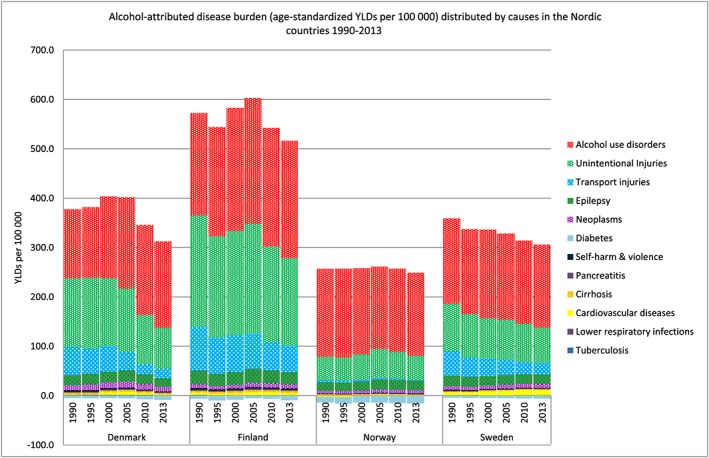

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the alcohol‐attributed burden by causes, separated by premature mortality (age‐standardized YLLs per 100 000) and years lived with disability (age‐standardized YLDs per 100 000) (see the Supporting information, Tables S3 and S4 for details). The causes by YLLs follow a similar pattern as for DALYs, largely because the majority of DALYs are caused by YLLs from alcohol use disorder, cirrhosis, transport injuries, self‐harm and violence and neoplasms. One difference is that YLLs attributable to alcohol use disorder and unintentional injuries were less prominent compared to other causes. Instead, alcohol use disorder and unintentional injuries make an important contribution to DALYs through YLDs.

Figure 3.

Alcohol‐attributed disease burden [age‐standardized years of life lost (YLLs) per 100 000] distributed by causes in the Nordic countries 1990–2013

Figure 4.

Alcohol‐attributed disease burden [age‐standardized years lived with disability (YLDs) per 100 000] distributed by causes in the Nordic countries 1990–2013

The YLDs did not follow a similar pattern to YLLs. For example, for alcohol use disorder, the largest contributor to YLDs in all countries, the gap in burden between Norway and Sweden compared to Finland was not as pronounced as for YLLs (Fig. 4). In 1990 and 2013, YLDs from alcohol use disorders accounted for 48 and 63% of DALYs in Norway and 55 and 64% in Sweden, while in Finland the corresponding contribution was 40–49% and 40–41% in Denmark (not shown). In Norway and Sweden YLDs by alcohol use disorder have been rather stable over time. Thus the decrease in DALYs of alcohol use disorder over time was due mainly to decreased YLLs.

Discussion

Our study shows that Finland and Denmark had a higher alcohol‐attributed disease burden than Sweden and Norway in the period 1990–2013 and that changes in consumption levels in general corresponded to changes in harm in Finland and Denmark, but not for some years in Sweden and Norway. All countries followed a similar disease pattern. The majority of DALYs were due to YLLs from alcohol use disorder, cirrhosis, transport injuries, self‐harm and violence and neoplasms that generally decreased over time. The exceptions were that YLLs of alcohol use disorder in Finland and Denmark and cirrhosis in Finland increased between 2000 and 2005. In contrast to YLLs, alcohol use disorder by YLDs accounted for a higher proportion of DALYs in Norway and Sweden, compared to Finland and Denmark. Finland and, to some extent, Denmark and Sweden also had a relatively high burden of non‐fatal unintentional injuries.

Our results on premature mortality correspond to other studies, showing higher mortality 3, 11 from cirrhosis, injuries and neoplasms in Finland and Denmark compared to Norway and Sweden. Moreover, it has been estimated that cirrhosis, injuries and neoplasm are responsible collectively for approximately 80% of alcohol‐related deaths in the European Union (EU) 3. In our study premature mortality from alcohol use disorders also contributed significantly.

Comparative studies assessing alcohol‐related morbidity in the Nordic countries are lacking. Some studies have evaluated alcohol‐related morbidity in relation to specific alcohol policy changes 22, 23, 24, 25, 26. These studies are based on different health outcomes and do not enable an overall comparison. The fact that YLDs accounted for a higher proportion of DALYs in Norway and Sweden compared to Finland and Denmark may be due to differences in treatment practices and improvement in survival rate from alcohol use disorders, or differences in underlying data. Further research is needed to understand this difference, but our results highlights the importance of including non‐fatal harm when estimating the burden of alcohol‐attributed adverse health effects.

In general, the variation in alcohol‐attributed disease burden over time corresponded to changes in levels of alcohol consumption in Denmark and Finland, although comparison to Finland's own statistical data suggests that the increase from 1990 to 2005 might have been somewhat underestimated 27. In Sweden and, to some extent, in Norway the burden of disease did not increase, although the GBD estimates show increased consumption during the past 10 years. However, there are also exceptions for Finland and Denmark when looking at specific causes of disease burden. For one thing, self‐harm and violence decreased in Finland even if the overall consumption increased, as did premature mortality from alcohol use disorder in Norway. The importance of drinking patterns in the association between levels of alcohol consumption and alcohol‐attributed mortality has been described previously 12, and some causes may be influenced more strongly by drinking patterns. This could also be due to differences in subgroups, such as sex, specific age groups or socio‐economic groups 28.

The separation of alcohol‐attributed causes may give an indication of the consumption patterns and also have implications for specific policy measures, both in the field of prevention and treatment. The burden of alcohol use disorder in all countries and cirrhosis, especially in Finland and Denmark, may reflect a pattern of frequent and heavy chronic drinking 29, 30, while the burden of injuries implies risky single‐occasion drinking 31. In the case of neoplasms, where the overall tissue exposure to alcohol has no lower threshold 20, 32, any level of drinking is important. The estimated beneficial effects of low to moderate alcohol consumption for cardiovascular outcomes and diabetes, resulting in negative DALYs, were seen mainly in Norway and Sweden, which may reflect a pattern of low to moderate drinking.

Availability of alcohol and high taxes are effective policies 33 and these form the basis of the restrictive alcohol polices still in place, especially in Norway and Sweden, while in Finland since the mid‐1990s the alcohol policies were liberalized considerably. In Denmark the high taxation of spirits was lowered in beginning of 2000. While several studies have analysed the effect of specific alcohol policy changes in relation to consumption and health outcomes in these countries 5, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, these types of studies in general require more detailed time‐specific data than provided herein. However, our findings, particularly regarding Finland, show that the variations in alcohol‐attributed burden of disease follow variations in alcohol policy measures 34. Also, changes in alcohol‐attributed disease burden in Sweden and Norway are related to policy changes as an effect of, for example, EU regulations, and the health effects in this study add to the ongoing debate on the consequences of these policy changes.

There are limitations that need to be addressed. One is the quality and validity of data. Per‐capita consumption is often underestimated. For this purpose a correction factor is used in the GBD calculation to account for unrecorded consumption 1. Moreover, even if estimates of levels of alcohol consumption in the GBD study largely match national surveys, there are data points where they differ. For example, contrary to the GBD estimates, Swedish data show that consumption levels actually increased from 1995 to 2000 and decreased between 2005 and 2010 35. This can be explained by the GBD methodology, in which multiple data sources are used. Furthermore, data on fatal outcomes are based on cause of death registers. Alcohol‐attributed deaths tend to be under‐reported in registers due to difficulties in making accurate diagnoses. Coding practices also differ across countries 36. The GBD study uses a general approach to assess causes of death from all countries. However, little is known about to what extent differences in coding affect the estimates.

Another limitation concerns the relative risk estimates of the associations between alcohol and disease or mortality outcomes. These derive from meta‐analyses which postulate comparability between countries. This is one of the assumptions inherited in the GBD methodology, and although plausible in view of biological pathways there could be unmeasured interactions between alcohol and other risk factors that differ between countries. Because the relative risk estimates from the meta‐analyses derive mainly from high‐income countries, the comparability between Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland should hardly be biased.

A key strength with the GBD methodology is that disease burden due to alcohol is defined systematically and uniformly, also for non‐fatal health outcomes, and thus estimates can be compared across countries over time. Data on non‐fatal outcomes are based mainly on scientific studies reflecting the country prevalence of diseases. Even if Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland have comparatively high‐quality records and registers, the underlying data are sometimes incomplete and not timely 18 and the results should be interpreted with caution. It should also be mentioned that the GBD methodology differs from many national studies in this area, and results are not always comparable with country‐specific studies.

In conclusion, we have shown a method to provide a comparative assessment of alcohol‐attributed disease burden across four Nordic countries. The inclusion of alcohol‐attributed non‐fatal conditions, not only with regard to alcohol use disorder, but also injuries, makes an important contribution to the overall burden. As the GBD study will be shifting towards annual updating, these results may be used as a future regular monitoring system to assess and compare alcohol‐attributed disease burden over time and across countries once new and updated data in this field become available.

Declaration of interests

None.

Supporting information

Table S1 Detailed diagnoses of causes.

Table S2 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by agestandardized DALYs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Table S3 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by age‐standardized YLLs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Table S4 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by age‐standardized YLDs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

This study was supported from grants from the Alcohol Research Council of the Swedish Alcohol Retailing Monopoly (SRA).

Agardh, E. E. , Danielsson, A. ‐K. , Ramstedt, M. , Ledgaard Holm, A. , Diderichsen, F. , Juel, K. , Vollset, S. E. , Knudsen, A. K. , Minet Kinge, J. , White, R. , Skirbekk, V. , Mäkelä, P. , Forouzanfar, M. H. , Coates, M. M. , Casey, D. C. , Naghavi, M. , and Allebeck, P. (2016) Alcohol‐attributed disease burden in four Nordic countries: a comparison using the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries and Risk Factors 2013 study. Addiction, 111: 1806–1813. doi: 10.1111/add.13430.

References

- 1. Forouzanfar M. H., Alexander L., Anderson H. R., Bachman V. F., Biryukov S., Brauer M. et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 2287–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gowing L. R., Ali R. L., Allsop S., Marsden J., Turf E. E., West R. et al. Global statistics on addictive behaviours: 2014 status report. Addiction 2015; 110: 904–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shield K . Status Report on Alcohol and Health in 35 European Countries 2013. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2013.

- 4. Bloomfield K., Stockwell T., Gmel G., Rehn N. International comparisons of alcohol consumption. Alcohol Res Health 2003; 27: 95–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leifman H., Österberg E., Ramstedt M. Alcohol in Postwar Europe: A Discussion on Indicators on Consumption and Alcohol‐Related Harm. Stockholm: European Comparative Alcohol Study (ECAS); 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murray C. J., Vos T., Lozano R., Naghavi M., Flaxman A. D., Michaud C. et al. Disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990‐2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Bank Investing in Health. World Development Report 1993; World Bank. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murray C. J., Barber R. M., Foreman K. J., Ozgoren A. A., Abd‐Allah F., Abera S. F. et al. Global, regional, and national disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015; 386: 2145–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naghavi M., Wang H., Lozano R., Davis A., Lang X., Zhou M. et al. Global, regional, and national age‐sex specific all‐cause and cause‐specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 385: 117–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karlsson T., editor. Nordic Alcohol Policy in Europe: the adaptation on Finland's, Sweden's and Norway's Alcohol Policies to a new framework, 1994–2013. Åbo: Juvenes Print, Finnish University Print Ltd; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramstedt M. Variations in alcohol‐related mortality in the Nordic countries after 1995– continuity or change? Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007; 24: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Norstrom T. Alcohol in Postwar Europe: Consumption, Drinking Patterns and Policy Response in 15 European Countries. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anderson P., Fleur Braddic, Reynolds J., Gual A., editors. Alcohol Policy in Europe: Evidence from AMPHORA The AMPHORA Porject; 2012. Available at: http://amphoraproject.net/viewphp?id_cont=45 (accessed 1 April 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vos T. B. R., Bell B., Bertozzi‐Villa A., Biryukov S., Bollinger I. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386: 743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lozano R., Naghavi M., Foreman K., Lim S., Shibuya K., Aboyans V. et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2095–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Salomon J. A., Vos T., Hogan D. R., Gagnon M., Naghavi M., Mokdad A., et al. Common values in assessing health outcomes from disease and injury: disability weights measurement study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380: 2129–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haagsma J. A., Maertens de Noordhout C., Polinder S., Vos T., Havelaar A. H., Cassini A. et al. Assessing disability weights based on the responses of 30,660 people from four European countries. Popul Heath Metrics 2015; 13: DOI: 10.1186/s12963-015-0042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Available at: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd‐2013‐data‐citations (accessed 1 April 2016).

- 19. Lim S. S., Vos T., Flaxman A. D., Danaei G., Shibuya K., Adair‐Rohani H. et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012. 15;; 380: 2224–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rehm J., Baliunas D., Borges G. L., Graham K., Irving H., Kehoe T. et al. The relation between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction 2010; 105: 817–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shield K. D., Rylett M., Gmel G., Kehoe‐Chan T. A., Rehm J. Global alcohol exposure estimates by country, territory and region for 2005—a contribution to the Comparative Risk Assessment for the 2010 Global Burden of Disease Study. Addiction 2013; 108: 912–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gustafsson N. K., Ramstedt M. R. Changes in alcohol‐related harm in Sweden after increasing alcohol import quotas and a Danish tax decrease—an interrupted time–series analysis for 2000–2007. Int J Epidemiol 2011; 40: 432–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Norstrom T., Skog O. J. Saturday opening of alcohol retail shops in Sweden: an experiment in two phases. Addiction 2005; 100: 767–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bloomfield K., Wicki M., Gustafsson N. K., Makela P., Room R. Changes in alcohol‐related problems after alcohol policy changes in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2010; 71: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bloomfield K., Rossow I., Norstrom T. Changes in alcohol‐related harm after alcohol policy changes in Denmark. Eur Addict Res 2009; 15: 224–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rossow I., Norstrom T. The impact of small changes in bar closing hours on violence. The Norwegian experience from 18 cities. Addiction 2012; 107: 530–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yearbook of Alcohol and Drug Statistics Official Statistics of Finland. National Institute for Health and Welfare: Helsinki; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ramstedt M. Change and stability? Trends in Alcohol consumption, harms and policy: Sweden 1990–2010. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs 2010; 24: 409–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rehm J., Taylor B., Mohapatra S., Irving H., Baliunas D., Patra J. et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev 2010; 29: 437–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rehm J., Roerecke M. Reduction of drinking in problem drinkers and all‐cause mortality. Alcohol Alcohol 2013; 48: 509–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shield K. D., Gmel G., Patra J., Rehm J. Global burden of injuries attributable to alcohol consumption in 2004: a novel way of calculating the burden of injuries attributable to alcohol consumption. Popul Health Metr 2012; 10: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bagnardi V., Rota M., Botteri E., Tramacere I., Islami F., Fedirko V. et al. Light alcohol drinking and cancer: a meta‐analysis. Ann Oncol 2013; 24: 301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andreasson S., Holder H. D., Norstrom T., Osterberg E., Rossow I. Estimates of harm associated with changes in Swedish alcohol policy: results from past and present estimates. Addiction 2006; 101: 1096–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Karlsson T., Österberg E., Tigerstedt C. A new alcohol environment. Trends in alcohol consumption, harms and policy: Finland 1990–2010. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs 2010; 27: 497–513. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Trolldal B., Leifman H. Hur mycket dricker svensken? Registrerad och oregistrerad alkoholkonsumtion [How much do Swedes drink? Registered and unregistered alcohol consumption]. CAN‐rapport nr 152. 2015; Centralförbundet för alkohol‐och narkotikaupplysning. Stockholm, Sverige.

- 36. Ågren G., Jacobsson S. W. Validation of diagnoses on death certificates for male alcoholics in Sweden. Forensic Sci 1987; 33: 231–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Detailed diagnoses of causes.

Table S2 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by agestandardized DALYs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Table S3 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by age‐standardized YLLs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Table S4 Alcohol‐attributed disease burden by age‐standardized YLDs per 100 000 and (95% uncertainty intervals) distributed by causes in the Nordic countries.

Supporting info item