Abbreviations

- VTH

veterinary teaching hospital

- NBP

aminobisphosphonate

- ZOL

zoledronate

- OS

osteosarcoma

- BRONJ

bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw

- VDL

veterinary diagnostic laboratory

- CT

computed tomography

- NTx

urine N‐terminal telopeptide

Case History

An 11.5‐year‐old castrated, male Saint Bernard dog presented to the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH) for continued treatment with monthly intravenous (IV) zoledronate (ZOL) for the management of bone pain associated with osteosarcoma (OS) of the left proximal humerus. Recently, the pet owner had observed ptyalism and bleeding from the right side of the dog's mouth. On physical examination, the source of bleeding could not be identified, but diffuse and severe dental calculus accumulation and periodontal disease were noted. Past pertinent medical history before onset of ptyalism and oral cavity hemorrhage was that the dog had been evaluated 3.5 years earlier for progressive left forelimb lameness, diagnosed with appendicular OS involving the left humerus, and effectively treated for bone cancer pain with ionizing radiation treatment (RT) to the primary appendicular lesion for a total of 20 gray, and recurring IV ZOL treatment (0.1 mg/kg every 28 days), indefinitely for as long as malignant skeletal pain was controlled. Monthly infusions of ZOL continued for 46 consecutive months in combination with oral analgesics including carprofen at 2.2 mg/kg PO every 12 hours, tramadol 2 mg/kg PO every 12 hours, and gabapentin 3 mg/kg PO every 24 hours. Before each ZOL infusion, a serum chemistry panel was performed to assess renal function with no significant abnormalities noted throughout the course of treatment. Additionally, given the highly metastatic behavior of osteosarcoma, three‐view thoracic radiographs were taken at varying intervals of at least every 4 months throughout the course of ZOL treatment to monitor for the development of pulmonary metastasis.

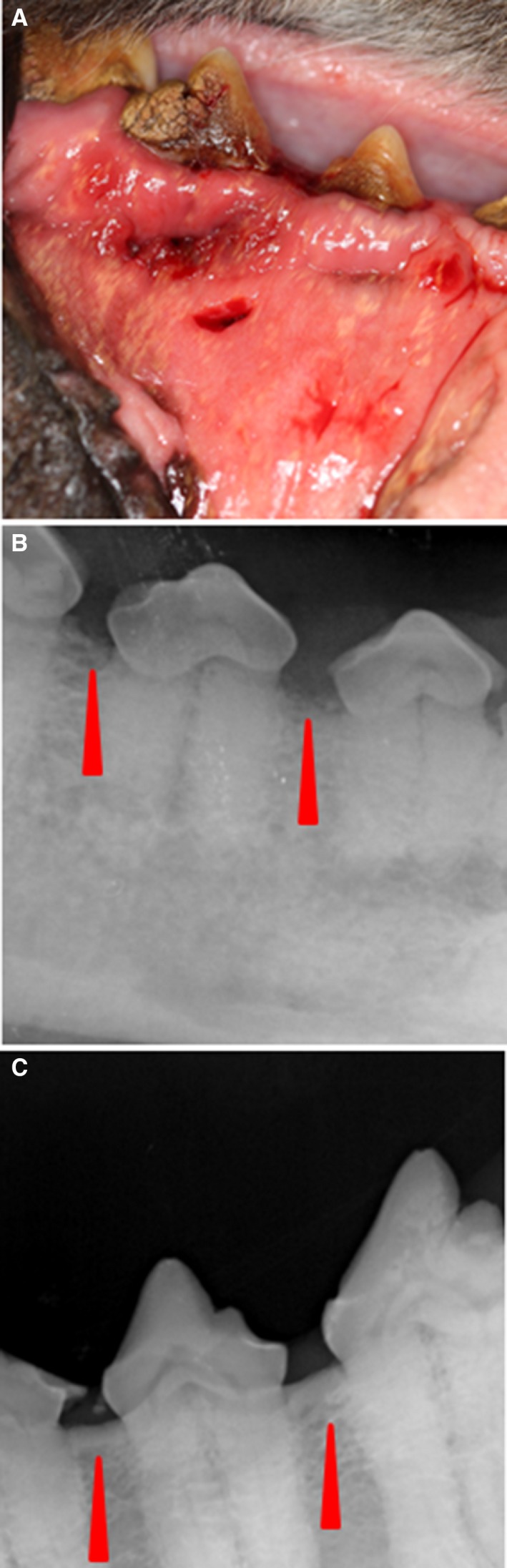

Three weeks after the initial complaint of ptyalism and bleeding from the right side of the mouth, the dog represented to the VTH dentistry service for further evaluation. The dog was placed under general anesthesia for an oral examination, dental radiographs, and periodontal cleaning. Oral examination findings included moderate generalized gingivitis with heavy calculus that was worse on the right mandible, mucosal draining tracts on the right mandibular buccal mucosa at the mucogingival line of the premolars and first molar (Fig 1A), draining tracts on the floor of the mouth under the tongue from which purulent material was expressed, gingival recession and furcation exposure of the right mandibular fourth premolar with friable gingiva, and pockets 8–10‐mm deep on the buccal side of the right mandibular third and fourth premolars. Dental radiographs of the left and right mandibles were performed and compared. The left mandible was radiographically normal (Fig 1C); however, radiographic abnormalities of the right mandible identified were mottled alveolar bone adjacent to the right premolars and slight bony proliferation at the ventral cortex with 3–4 mm loss of the bony dorsal alveolar margin at the mandibular third and fourth premolars (Fig 1B). Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were taken from draining tracts, and a bone biopsy of the right mandible at the level of the fourth premolar was taken before cleaning. Histopathologic findings of the right mandible were consistent with bacterial osteomyelitis, with no evidence of neoplasia or osteonecrosis being identified. Bacterial cultures yielded aerobic and anaerobic colonies for which appropriate antibiotic treatment was prescribed. Given the severity of the mandibular lesion, surgical debridement of the affected area and partial mandibulectomy were recommended, but was declined by the pet owner, and only systemic antibiotic treatment was instituted. At this time, discontinuation of ZOL treatment was recommended given the known risk factors associated with the development of bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) in people receiving chronic antiresorptive therapies. In total, the dog had received 46 consecutive monthly IV ZOL treatments and a cumulative dosage of 283.5 mg.

Figure 1.

Gross and radiographic abnormalities at evaluation on presentation to the dentistry service. (A) Draining tracts along buccal service of mucogingival line ventral to premolars and first molar. (B) Loss of the bony dorsal alveolar margin at the third and fourth premolars of right mandible (red arrows). (C) Normal dorsal alveolar margin of the left mandible for comparison (red arrows).

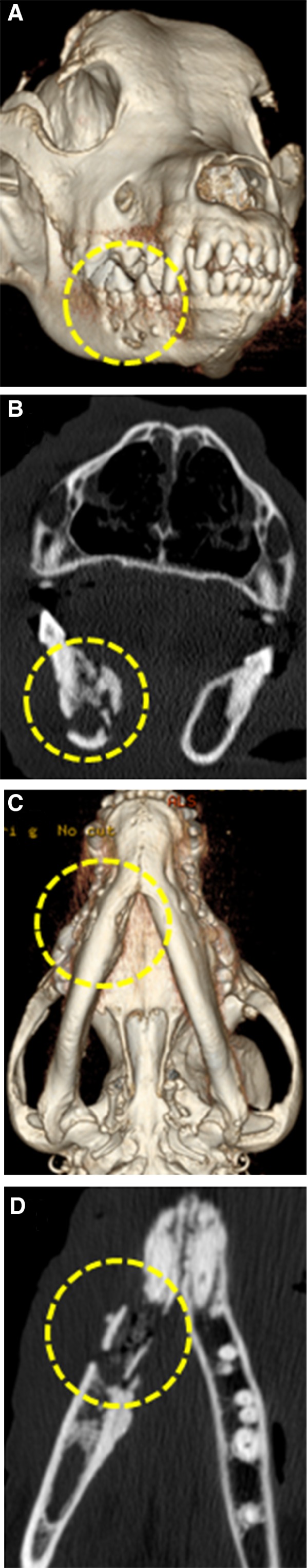

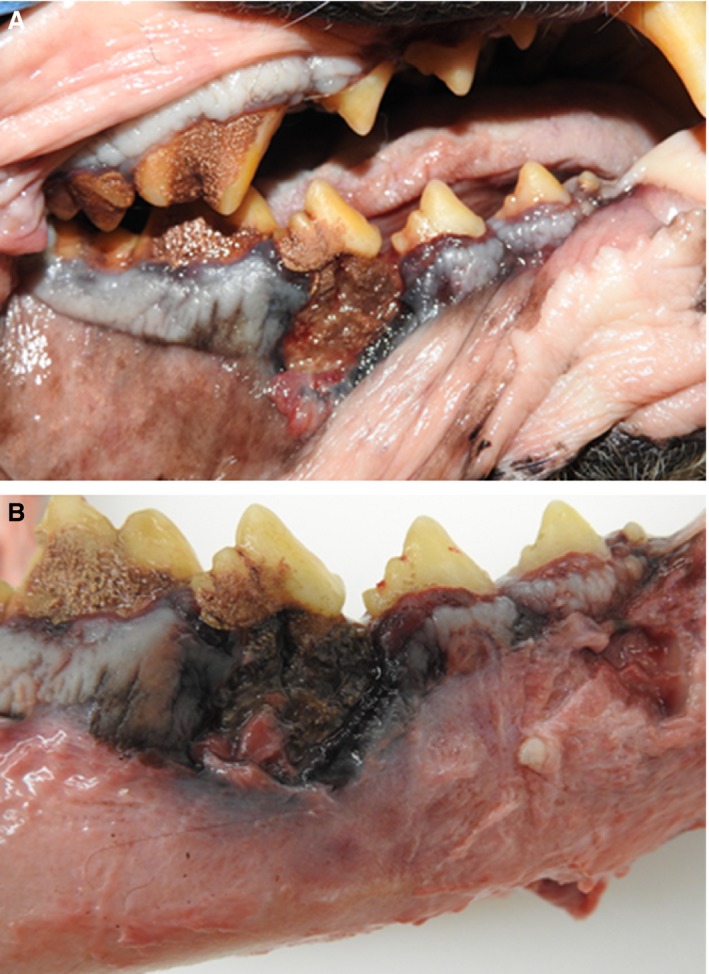

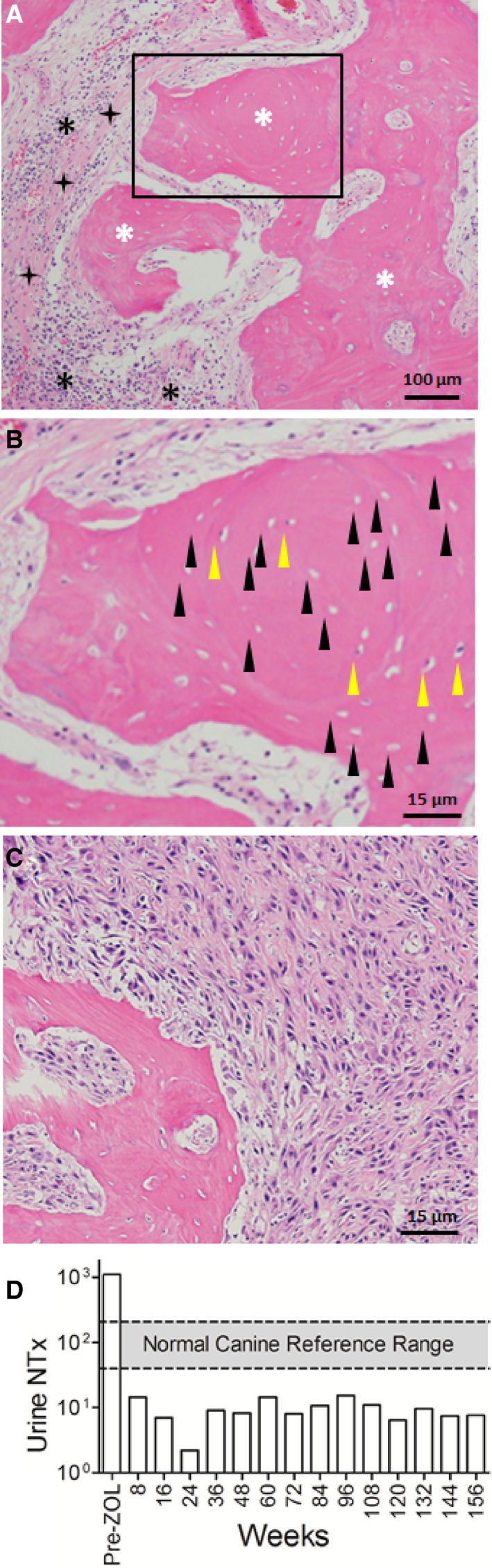

The pet owner elected to continue treatment with oral pain medications alone and did not pursue additional palliative strategies given the dog's age and protracted history of OS. Conservative treatment with oral analgesics continued for 13 additional months until the dog was represented to the VTH Cancer Care Clinic for humane euthanasia after developing acute nonambulatory paresis, respiratory distress, and progressive oral cavity bleeding. Before this acute presentation, the dog was last evaluated at the VTH 3.5 months earlier where three‐view thoracic radiographs did not show evidence of pulmonary metastatic disease. A brief oral examination before euthanasia was performed and a large necrotic defect involving the right mandible was identified. Immediately postmortem, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the skull was performed before full necropsy. The CT scan of the skull identified periosteal proliferation and sections of cortical disruption of the right mandible with gas attenuating structures in the alveolar cavity consistent with osteomyelitis or neoplasia with concurrent osteonecrosis (Fig 2). Upon gross evaluation at necropsy, the right mandible had an ulceration measuring 1.5 cm × 2 cm involving the buccal gingiva ventral to the fourth premolar with exposure of the underlying bone (Fig 3). Additional gross findings were a mass adhered to the left first rib, a mass on the left proximal humerus, multiple pulmonary masses, and multiple kidney masses, which were all confirmed to be OS by histopathology. No gross abnormalities were noted on any of the other long bones, and histology and imaging (such as CT or radiographs) were not performed on grossly normal bone. Histology of the right mandible showed multifocal to coalescing areas of osteonecrosis, which were characterized by fragments of necrotic bone with empty lacunae that were void of lining osteoblasts. Fibrosis and inflammation, which ranged from lymphoplasmacytic to suppurative with bacteria, separated and partially surrounded the areas of osteonecrosis (Fig 4A & B). Additionally, in discrete sections infiltrative malignant osteoblasts, consistent with OS, were partially effacing and replacing portions of the right mandibular bone (Fig 4C). Serial quantification of urine N‐telopeptide (NTx) over the span of the 156 weeks while the dog was receiving treatment confirmed that the use of ZOL dramatically attenuated homeostatic and pathologic bone resorption, consistent with the mechanism of action of bisphosphonates, being the inhibition of osteoclastic activities (Fig 4D).

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan of head postmortem with lesion circled in yellow dashed line highlighting periosteal proliferation and sections of cortical disruption of the right mandible. (A) 3‐dimensional reconstruction of skull; rostro‐lateral view; (B) Transverse image of mandible with destructive osteolysis; (C) 3‐dimensional reconstruction showing ventral aspect of the mandible with undulating medial cortical margins of the right rostral mandible; (D) Coronal plane image of right mandibular lesion demonstrating mixed osteolysis and osteoproduction.

Figure 3.

Gross abnormalities on necropsy. (A) Nonhealing mucosal ulceration with consequent exposed right mandibular bone ventral to fourth premolar; (B) Right mandible with overlying soft tissue removed to allow full visualization of exposed necrotic mandibular lesion.

Figure 4.

Histopathology of right mandible postmortem and urine NTx concentrations. (A) 100× magnification—white asterisks denote regions of mandibular bone; black asterisks identify pockets of suppurative and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with bacterial colonies; black 4‐point stars signify areas of bridging fibrosis. (B) Blow up view of rectangular region with black arrow heads highlighting the presence of many empty lacunae with no osteocytes (hallmark of osteonecrosis), and yellow arrow heads showing only a few viable osteocytes within lacunae. (C) Discrete pockets of neoplastic osteoblasts effacing select regions of the mandible. (D) Graphical presentation of urine NTx concentration over time in weeks. Prezoledronate treatment levels exceed the normal canine reference range.26 After zoledronate treatment, levels remain below the normal reference range throughout the course of treatment.

Discussion

Bisphosphonates belong to a class of drugs that are commonly used to stabilize bone loss associated with osteoporosis in women, and work by inhibiting the resorption of trabecular bone by osteoclasts, thereby increasing bone mineral density and reducing the risk of fractures. The use of more potent aminobisphosphonates (NBP), including ZOL and pamidronate, are administered IV in the management of a myriad of malignant skeletal pathologies such as metastatic bone lesions (particularly breast and prostate cancers), multiple myeloma, and hypercalcemia of malignancy.1 Given their wide safety margin when combined with conventional cytotoxins and effective antiresorptive characteristics, NBP are considered first‐line therapies for managing skeletal complications of malignancy.2

With the widespread institution of bisphosphonates for managing skeletal disorders, the observations of infrequent adverse toxicities have emerged over the past decade. One such toxicity is the association of bisphosphonate treatment and osteonecrosis of the jaw in human cancer patients, which was first documented by Marx in 2003.3 Subsequently, multiple studies documenting this infrequent, yet clinically significant, adverse consequence of chronic bisphosphonate usage have been reported.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 This condition is recognized as bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) by the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) which describes three characteristics that are necessary to consider a patient to have BRONJ and includes, (1) current or previous treatment with a bisphosphonate; (2) exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than 8 weeks; and (3) no history of radiation treatment to the jaws.10

An exact mechanism of BRONJ has not been determined, however, there are several hypotheses. In most cases, pathogenesis of this process is consistent with a defect in jawbone remodeling or wound healing with the most prevalent being the inhibition of osteoclast function, with consequent attenuation of normal bone turnover to an extent that local microdamage from normal load or injury (infection, dental procedure) cannot be repaired.11 Interestingly, in the 13 years that this condition has been recognized, bisphosphonate osteonecrosis has been reported almost solely in the craniofacial skeleton outside of a few reports where this was documented in the external ear canal, hips, femur, and tibia.12, 13, 14 This preferential anatomic distribution could be explained by the two unique components of the maxilla and mandible, being alveolar bone and periodontium.15 These bony structures possess a high rate of homeostatic turnover and maintain an accelerated remodeling status throughout life. In people, the remodeling rate of the cortical bone of the jaw is 10–20 times faster than that of the iliac bone. Bone remodeling is a coordinated process between osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and disruption of this delicate balance can lead to either increase or decrease in bone mineral density and skeletal health. Bisphosphonate therapies are preferentially deposited in bones that have a high turnover rate, and once incorporated into bone the long half‐life of bisphosphonates favors prolonged persistence within the bone microenvironment.11 Collectively, these unique biologic features of jaw bones and chemical properties of bisphosphonates, provide mechanistic explanations for the preferentially localized of BRONJ to the craniofacial skeleton.

In an attempt to understand the etiopathogenesis of BRONJ, multiple risk factors have been prospectively identified in association with BRONJ development. In a 2006 review of 368 cases of BRONJ in people, greater than 90% of BRONJ cases were linked to treatment with a NBP, such as pamidronate or ZOL; and additional risk factors included total dose of bisphosphonate administered, history of trauma, surgery, or dental infection.9 Given the 100‐fold greater antiresorptive potency of ZOL compared to pamidronate, people receiving ZOL were at higher risk of BRONJ development, with median duration of drug use ranging from 22–39 months. In a contemporaneous review of 4019 patients treated with IV bisphosphonates, the incidence of BRONJ ranged from 1.2–2.4%, and people who developed BRONJ had been treated for longer periods of time than those who did not, and other risk factors identified in this review were treatment with ZOL, poor oral health, and dental extractions.7

Dogs have a similar rate of bone remodeling in the jaw compared to humans (3 months versus 4–6 months, respectively),16, 17 and provides biologic justification to include canines as a model to study the pathogenesis of BRONJ development in humans.16, 18, 19 Such a research strategy has been employed by various investigative teams, and include a 2008 study whereby 12 research beagles were treated daily with oral alendronate for 3 years, which demonstrated that bone turnover was significantly reduced and matrix necrosis of the mandible was observed in 25–33% of the beagles treated compared to no matrix necrosis in the vehicle‐treated dogs.16 Other animal model studies have shown the ability to induce BRONJ in mini‐pigs treated with ZOL and tooth extractions,20 and in sheep treated with ZOL followed by tooth extractions.21

Bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw has not been described in companion animals outside of experimental conditions,16, 18, 19 although concern for this becoming a complication in veterinary patients has been raised by the veterinary dental community and published by Stepaniuk in 2011.22 As such, this case report provides valuable information on an infrequent, yet clinically significant, adverse effect of prolonged bisphosphonate treatment. Given that bisphosphonate treatment is widely used for the management of diverse skeletal pathologies in companion animal species, including non‐neoplastic conditions such as idiopathic hypercalcemia in cats,23, 24, 25, 26 the documentation of potential adverse effects would heighten awareness of veterinary health professionals for infrequent complications associated with systemic antiresorptive therapies. We report here a case of BRONJ, although other concerning sequelae to long‐term NBP usage in humans, such as atypical long bone fractures,27 might be similarly a rare clinical consequence attributed to long‐term use in veterinary patients.

In the current case report, the affected dog exhibited many of the above‐listed risk factors associated with BRONJ development including long‐term use of ZOL, a high cumulative drug dose (283.5 mg), prolonged treatment duration (46 months), and severe periodontal infection. Additionally, the histopathology report identified the presence of concurrent bacterial colonization within the necrotic bone, which is a finding previously reported in biopsied diagnoses of BRONJ.4 Importantly, inhibition of osteoclastic activities after ZOL treatment was confirmed by the serial measurement of urine N‐telopeptide (NTx), a surrogate biomarker of bone turnover validated in people and dogs.28, 29 This dog demonstrated a sustained and dramatic ~100‐fold reduction in homeostatic and pathologic bone resorption over the course of 156 weeks compared with baseline, and it is plausible that this prolonged suppression of bone remodeling capabilities, in concert with other risk factors, predisposed this dog to BRONJ development. In people, the time frame from inciting cause such as a tooth extraction, to development of BRONJ, is variable and can be several months.6, 8 In this dog, a significant amount of time passed (13 months) from recognition of a potential inciting cause, being osteomyelitis, to the diagnosis of BRONJ. There was no follow‐up regarding the osteomyelitis after initial diagnosis, and therefore it is difficult to determine the true time frame of BRONJ development in this dog.

The concurrent diagnosis of osteonecrosis associated with underlying osteomyelitis and tandem with OS were unexpected histologic findings, as people diagnosed with BRONJ, underlying malignancy has been identified in only a small number of cases. In a 2001 case and literature review of 121 patients with BRONJ who were treated surgically, three patients were found to have underlying neoplasia mimicking BRONJ.30 In this dog, biopsy of the right mandible 13 months before euthanasia did not identify histologic evidence of OS based upon an incisional biopsy. However, small biopsies do run the risk of missing underlying malignancy, and it is not possible to determine if this dog developed OS secondary to chronic osteomyelitis, or if metastatic OS and osteomyelitis developed concurrently. Regardless, serially developing or contemporaneously arising bone pathologies identified in this pet dog would nonetheless serve as stimulators of reparative bone‐healing responses which were effectively inhibited by long‐term ZOL treatment; resulting in impaired skeletal remodeling and repair, with consequent osteonecrosis development.

With the advent of improved palliative strategies for the management of bone cancer pain it would be expected that veterinary health professionals will need to consider and practice judicious administration of long‐term analgesic strategies, which might include NBP therapies. As such, this case report might serve to inform veterinarians who prescribe these drugs to animals that long‐term antiresorptive agents can produce infrequent, yet clinically significant, adverse effects such as BRONJ. With heightened vigilance for this rare complication associated with NBP therapies, early and appropriate interventional steps should be considered. The specialists in veterinary dentistry currently recommend that thorough dental screenings before NBP use be performed, severely diseased teeth should be extracted, and routine oral hygiene be implemented by pet owners as the best way to prevent the development of BRONJ.22

Acknowledgment

The study was not supported by a grant.

Conflict of Interest Declaration: Timothy M. Fan serves as Associate Editor for the Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. He was not involved in review of this manuscript.

Off‐label Antimicrobial Declaration: Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

The case has not been presented at any meetings.

References

- 1. Terpos E, Confavreux CB, Clezardin P. Bone antiresorptive agents in the treatment of bone metastases associated with solid tumours or multiple myeloma. BoneKEy Reports 2015;4:744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh T, Kaur V, Kumar M, et al. The critical role of bisphosphonates to target bone cancer metastasis: an overview. J Drug Target 2015;23:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61:1115–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bamias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer after treatment with bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8580–8587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bezerra Ribeiro NR, de Freitas Silva L, Matos Santana D, et al. Bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction. J Craniofac Surg 2015;26:e606–e608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Estilo CL, Van Poznak CH, Wiliams T, et al. Osteonecrosis of the maxilla and mandible in patients with advanced cancer treated with bisphosphonate therapy. Oncologist 2008;13:911–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hoff AO, Toth BB, Altundag K, et al. Frequency and risk factors associated with osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. J Bone Miner Res 2008;23:826–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee BD, Park MR, Kwon KH. Bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a multiple myeloma patient: A case report with characteristic radiographic features. Imaging Sci Dent 2015;45:199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Woo SB, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Narrative [corrected] review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Assael LA, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw – 2009 update. Aust Endod J 2009;35:119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruggiero SL. Guidelines for the diagnosis of bisphosphonate‐related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab 2007;4:37–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Froelich K, Radeloff A, Kohler C, et al. Bisphosphonate‐induced osteonecrosis of the external ear canal: a retrospective study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2011;268:1219–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta S, Jain P, Kumar P, et al. Zoledronic acid induced osteonecrosis of tibia and femur. Indian J Cancer 2009;46:249–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Polizzotto MN, Cousins V, Schwarer AP. Bisphosphonate‐associated osteonecrosis of the auditory canal. Br J Haematol 2006;132:114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bertoldo F, Santini D. Lo Cascio V. Bisphosphonates and osteomyelitis of the jaw: a pathogenic puzzle. Nat Clin Pract Onco 2007;4:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Allen MR, Burr DB. Mandible matrix necrosis in beagle dogs after 3 years of daily oral bisphosphonate treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;66:987–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boyce RW, Paddock CL, Gleason JR, et al. The effects of risedronate on canine cancellous bone remodeling: three‐dimensional kinetic reconstruction of the remodeling site. J Bone Miner Res 1995;10:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Allen MR. Animal models of osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2007;7:358–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burr DB, Allen MR. Mandibular necrosis in beagle dogs treated with bisphosphonates. Orthod Craniofac Res 2009;12:221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pautke C, Kreutzer K, Weitz J, et al. Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A minipig large animal model. Bone 2012;51:592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Voss PJ, Stoddart M, Ziebart T, et al. Zoledronate induces osteonecrosis of the jaw in sheep. J Cranio‐Maxillo‐Facial Surg 2015;43:1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stepaniuk K. Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a review. J Vet Dentist 2011;28:277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fan TM. The role of bisphosphonates in the management of patients that have cancer. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2007;37:1091–1110; vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fan TM, de Lorimier LP, Garrett LD, et al. The bone biologic effects of zoledronate in healthy dogs and dogs with malignant osteolysis. J Vet Intern Med 2008;22:380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hardy BT, de Brito Galvao JF, Green TA, et al. Treatment of ionized hypercalcemia in 12 cats (2006–2008) using PO‐administered alendronate. J Vet Intern Med 2015;29:200–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hostutler RA, Chew DJ, Jaeger JQ, et al. Uses and effectiveness of pamidronate disodium for treatment of dogs and cats with hypercalcemia. J Vet Intern Med 2005;19:29–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ernat J, Song D, Fazio M, et al. Radiographic changes and fracture in patients having received bisphosphonate therapy for >5 years at a single institution. Mil Med 2015;180(12):1214–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iba K, Takada J, Hatakeyama N, et al. Changes in urinary NTX levels in patients with primary osteoporosis undergoing long‐term bisphosphonate treatment. J Orthop Sci 2008;13:438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lacoste H, Fan TM, de Lorimier LP, et al. Urine N‐telopeptide excretion in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gander T, Obwegeser JA, Zemann W, et al. Malignancy mimicking bisphosphonate‐associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: a case series and literature review. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014;117:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]