Abstract

Hypothesis

A cochlear implant electrode within the cochlea contributes to the air-bone gap (ABG) component of postoperative changes in residual hearing after electrode insertion.

Background

Preservation of residual hearing after cochlear implantation has gained importance as simultaneous electric-acoustic stimulation allows for improved speech outcomes. Postoperative loss of residual hearing has previously been attributed to sensorineural changes; however, presence of increased postoperative air-bone gap remains unexplained and could result in part from altered cochlear mechanics. Here, we sought to investigate changes to these mechanics via intracochlear pressure measurements before and after electrode implantation to quantify the contribution to postoperative air-bone gap.

Methods

Human cadaveric heads were implanted with titanium fixtures for bone conduction transducers. Velocities of stapes capitulum and cochlear promontory between the two windows were measured using single-axis laser Doppler vibrometry and fiber-optic sensors measured intracochlear pressures in scala vestibuli and tympani for air- and bone-conducted stimuli before and after cochlear implant electrode insertion through the round window.

Results

Intracochlear pressures revealed only slightly reduced responses to air-conducted stimuli consistent with prior literature. No significant changes were noted to bone-conducted stimuli after implantation. Velocities of the stapes capitulum and the cochlear promontory to both stimuli were stable following electrode placement.

Conclusion

Presence of a cochlear implant electrode causes alterations in intracochlear sound pressure levels to air, but not bone, conducted stimuli and helps to explain changes in residual hearing noted clinically. These results suggest the possibility of a cochlear conductive component to postoperative changes in hearing sensitivity.

Keywords: Cochlear implant, electroacoustic stimulation, intracochlear pressures, air-bone gap, hearing preservation

Introduction

Cochlear implantation (CI) has been successfully used for decades to treat sensorineural hearing loss in patients who were receiving little to no benefit from traditional amplification. More recently, the candidacy criteria for cochlear implants has been expanded to include individuals with increasing amounts of residual hearing at low frequencies (<1000 Hz), and simultaneous electrical and acoustic stimulation (EAS) has demonstrated improved speech understanding in noise, localization, and music appreciation for these patients [1-8].

In order for patients to fully realize the benefits of EAS, acoustic hearing thresholds must be preserved after implantation; however, a subset of implanted patients have demonstrated worsened thresholds postoperatively [2, 9-14]. Loss of residual hearing following implantation has historically been attributed to sensorineural changes resulting from damage to neural elements, electrode fibrosis, or direct injury to the basilar membrane [15-26]. Despite clinical and basic science research focusing on minimizing surgical trauma [27-31], several reports have now demonstrated the presence of increased postoperative air-bone gap in a subset of patients [12-14] that remains unexplained. In a prospective study of patients undergoing cochlear implantation, 4 of 32 patients were found to have a new postoperative conductive component resulting in a mixed hearing loss [13]. This conductive impairment post-implantation may be related to changes in middle ear function, or it could result from altered cochlear mechanics [12].

In order assess alterations in cochlear mechanics, we report changes in intracochlear pressure before and after electrode implantation to both air- and bone-conducted stimuli. A previous report out of our lab showed that the presence of a CI electrode in the scala tympani altered intracochlear pressures measured during presentation of air-conducted stimuli, consistent with a mild hearing loss [31]. The goal of this investigation was to further quantify the contribution of the presence of an intracochlear electrode to postoperative air-bone gap by employing bone-conducted stimuli.

Methods

Data was collected and analyzed from five ears in fresh-frozen whole cadaveric heads. All specimens were confirmed to have intact temporal bones and verified to have no history of middle ear disease (Lone Tree Medical, Littleton, CO, USA). The use of cadaveric human tissue was in compliance with the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Institutional Biosafety Committee and Review Board (COMIRB EXEMPT #14-1464).

Temporal Bone Preparation

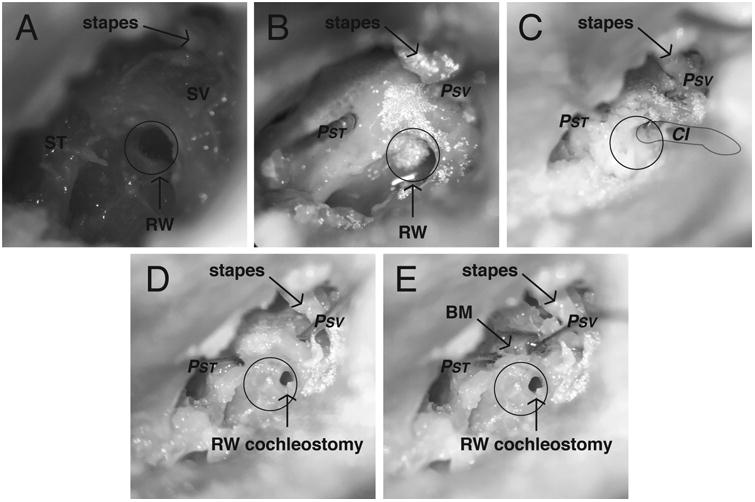

Temporal bone specimens were prepared as previously described by our laboratory [32-37], similar to methods that have been validated by Nakajima et al and Olson et al [38-40]. Figure 1 illustrates the steps of specimen preparation. Briefly, intact whole cadaveric heads were thawed overnight in warm water and inspected to rule out temporal bone, external or middle ear injury or disease. A canal-wall-up mastoidectomy with an extended facial recess approach was performed, employing frequent irrigation to avoid excess deposition of bone dust in the middle ear cavity. The cochlear promontory was thinned near the oval and round windows (Fig. 1A). Bone-conduction stimuli were generated using a commercially available bone-anchored sound processor affixed to an implanted titanium fixture. A 4-mm titanium implant (Cochlear Ltd., Centennial, CO, U.S.A.) was situated 50 mm from the external auditory canal. The specimens were acoustically isolated from other testing equipment via suspension by a Mayfield Clamp (Integra Lifesciences Corp., Plainsboro, NJ, U.S.A.) attached to a stainless steel baseplate. Cochleostomies into the scala tympani (ST) and scala vestibuli (SV) were created using a fine pick under a droplet of water, and fiber-optic pressure sensors (FOP-M260-ENCAP, FISO Inc., Quebec, QC, Canada) were inserted using micromanipulators (David Kopf Instruments, Trujunga, CA, U.S.A.) rigidly mounted onto the head clamp (Fig. 1B). Probes were sealed in place with alginate dental impression material (Jeltrate; Dentsply International Inc., York, PA). Pressure probe placements and basilar membrane location were verified after each experiment by dissecting the bone of the cochlear promontory between the two cochleostomy sites (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of the specimen (427L) preparation. Temporal bones of intact cephali underwent mastoidectomy with wide facial recess. Scala vestibuli (SV) and scala tympani (ST) were blue lined near the oval and round windows (RW) in preparation for the intracochlear pressure probes (A). Pressure probes (PSV and PST) were placed in cochleostomies in SV and ST, retroreflective glass beads placed on the stapes, promontory, and RW for LDV measurements (B). Implant electrode (CI) was inserted into the round window. All cochleostomies were sealed with dental impression material (C). The CI was removed and RW cochleostomy visualized (D). The bone between the SV and ST cochleostomies was dissected away to reveal the location of the basilar membrane (E).

Out-of-plane velocities of the stapes (VStap), round window and cochlear promontory were measured with a single-axis LDV (OFV-534 & OFV-5000; Polytec Inc., Irvine, CA) mounted to a dissecting microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany). Microscopic retro-reflective glass beads (P-RETRO 45-63 μm dia., Polytec Inc., Irvine, CA) were placed on the stapes and the cochlear promontory for measurement [41, 42].

Following Greene et al [31], cochleostomies for cochlear implant (CI) electrode insertion were made in the round window (RW) with a fine pick. Electrodes were inserted by hand underwater using an insertion tool, if provided by the manufacturer, and with a pair of fine forceps otherwise (Fig. 1C). CI electrodes used in these experiments were: Nucleus Hybrid L24 (HL24; Cochlear Ltd, Sydney, Australia), Nucleus CI422 Slim Straight inserted to 20 mm and 25 mm (SS20 & SS25; Cochlear Ltd, 95 Sydney, Australia), Nucleus CI24RE Contour Advance (NCA; Cochlear Ltd, Sydney, Australia), and HiFocus Mid-Scala (MS; Advanced Bionics AG, Stäfa, Switzerland). Electrodes were inserted one after another, in random order, and sealed in place with alginate dental impression material, and any remaining water was suctioned from the middle ear prior to data collection.

Sound Presentation, Data Acquisition, and Data Analysis

All experiments were performed in a double-walled sound-attenuating chamber (IAC Inc., Bronx, NY). Generation of sound stimuli and recording of responses was performed as described previously [32, 33, 43]. Briefly, stimuli were generated digitally, and presented via a bone conduction oscillator (Cochlear Ltd., Centennial, CO, U.S.A.) or a closed-field magnetic speaker (MF1; Tucker-Davis Technologies Inc., Alachua, FL) coupled directly to the ear with a foam insert altered to accommodate flexible speaker tubing. Both transducers were driven by an external sound card (Hammerfall Multiface II, RME, Haimhausen, Germany), and output directed to the loudspeaker was amplified with one channel of a stereo amplifier (TDT SA1). The sound intensity in the ear canal was measured with a probe-tube microphone (type 4182; Bruel & Kjær, Nærum, Denmark), which was also placed through the modified foam earplug. Baseline acoustic transfer functions were generated from presentation of short (1s duration) tone pips between 100 and 14000 Hz ramped on and off with one half (5 ms) of a Hanning window. Input from the microphone, LDV, and pressure sensors were simultaneously captured via the sound card analog inputs. The fiber-optic sensors were factory calibrated and sensitivity was verified by normalizing the sensor response to laser Doppler vibrometry displacement measurements made while generating a known motion in a cup of fluid controlled by a B&K mini-shaker (Bruel & Kjær Type 4810, Nærum, Denmark). The magnitude of the LDV signal was adjusted using a cosine correction (1/cos(θ)) based on an estimate of the difference in angle between the primary axis of the stapes and the orientation of the LDV laser (usually ∼45°). Signals acquired were band-pass filtered between 15-15000 Hz with a second order Butterworth filter.

Temporal bone measurements are shown as transfer functions, which consist of measured signal output normalized to stimulus input for each frequency, representing system gain. Differential pressure (PDiff) is calculated as the difference in pressures between scala vestibuli and scala tympani and represents the input to the cochlear partition and the driving force for auditory transduction. For air conduction measurements, scala vestibuli pressures were always greater than scala tympani pressures, resulting in positive values for differential pressures. With bone-conducted stimuli, scala vestibuli pressures were not always greater than the corresponding scala tympani pressures, so the differential pressures were calculated as absolute values. Responses were only analyzed for recordings with a signal to noise ratio greater than 6 dB, and SNR was higher than 10 dB for the majority of the recordings.

Results

Acoustic closed-field transfer functions

Baseline responses of VStap and intracochlear pressures (PIC) were assessed after placement of intracochlear pressure probes and prior to making the RW cochleostomy in order to verify the condition of each temporal bone. Closed field acoustic transfer function magnitudes (HACStap, HACSV, and HACST) for five specimens are shown in the upper panel of Figure 2. Responses were overlain onto the 95% CI for HACStap [44], and the mean+/-standard deviation of responses observed for HACSV and HACST reported previously by Nakajima et al [38]. Two specimens had intracochlear pressures outside the expected range, and both were found to have abnormal middle ear function as verified by stapes velocity measurements. Data collected from these specimens are illustrated by dashed lines in Figure 2 and were excluded from subsequent analyses. Responses collected from the remaining three specimens were consistent with previous reports [32, 33, 38-40]. Slightly higher than expected stapes velocities are seen at the highest frequencies tested when compared with results from other research groups; higher velocities are likely due to differences in setup or an unknown methodological issue. These changes are unlikely to be due to temporal bone pathology as the supplier verifies all specimens to be free of history of middle ear disease and normal middle ear anatomy is confirmed during specimen preparation. As seen in Fig.2, differential pressures to air conducted stimuli (HACDiff) were consistent with data seen in the literature [38] for specimens meeting inclusion criteria.

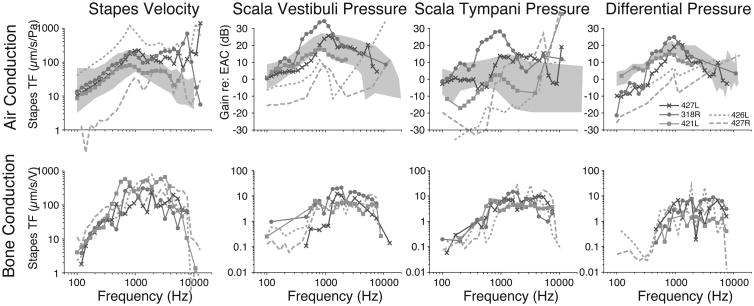

Figure 2.

Baseline VStap and SV and ST pressure (PSV/PST) transfer function magnitudes for air conduction (upper panel) and bone conduction (lower panel). Responses recorded in five specimens are shown normalized to the SPL recorded in the ear canal (PEC). Responses are superimposed onto the 95% CI and range of responses (gray bands) observed previously [44, 38]. Dashed lines indicate data that was excluded from analysis due to abnormal stapes mobility as shown by LDV measurements.

Bone conduction transfer functions

Baseline bone conduction transfer function magnitudes (HBCStap, HBCSV, and HBCST) for the five specimens are shown in the lower panel of Figure 2, with the two specimens not meeting criteria for inclusion shown again with dashed lines. Stapes transfer functions were similar to those seen with air-conducted stimuli, as well as data collected previously in our laboratory [33]. Intracochlear pressure responses were slightly lower than pressure recorded with air conduction, and the two pressures across the partition (PST and PSV) being more similar to one another when compared with air-conducted stimuli. Differential pressures (HBCDiff) are much lower with bone-conducted stimuli when compared with air conduction, a finding that is comparable to data published from our laboratory [33].

Effect of CI Electrode Insertion on Intracochlear Pressures

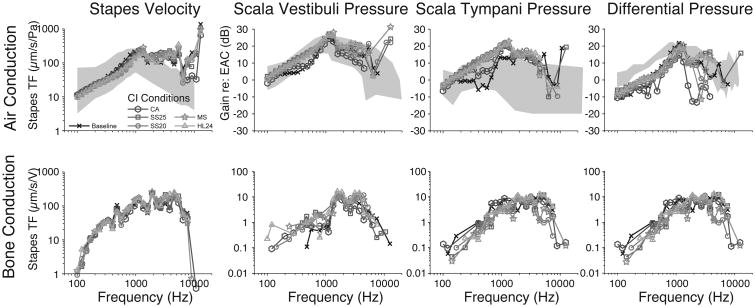

Figure 3 demonstrates an example set of transfer functions in one representative specimen (427L). Dark lines represent baseline transfer functions, whereas transfer functions recorded with CI electrodes inserted are shown with their respective gray shade as indicated by the figure legend. The upper panel shows the measurements made with air-conducted stimuli and the lower panel illustrates data for the same specimen with the same electrodes for bone-conducted stimuli. In general, there is some increase in intracochlear pressure for acoustic stimulation at low frequencies. There appears to be no substantial change in differential pressure, and no substantial changes for bone conduction data.

Figure 3.

An example set of recordings in one representative specimen (427L). Baseline transfer functions are represented by the darkest lines, whereas transfer functions recorded with various CI electrodes are identified with various markers in the legend. Transfer functions to air-conducted and bone-conducted stimuli are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively.

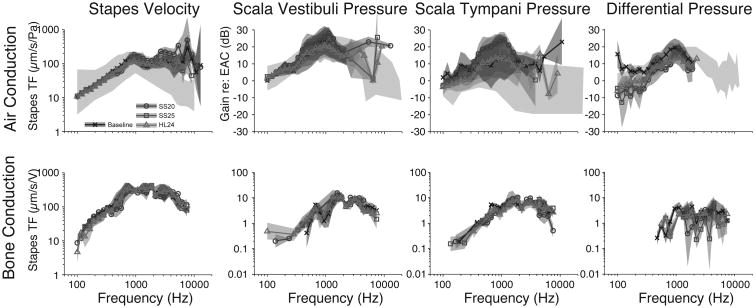

The same analysis across the population of specimens is shown in Figure 4. The upper panel shows the mean+/-SEM (light gray bands) transfer functions (HACStap, HACSV, HACST, and HACDiff) recorded under baseline (dark lines) and electrode-inserted conditions (corresponding shades of lighter gray) across the population of specimens for air-conducted stimuli. Differences are calculated with respect to baseline for each specimen and thus are shown only when at least two specimens were recorded with signal-to-noise ratios (SNR) greater than 3 dB in both the baseline and experimental conditions. Thus, comparisons are shown in Fig. 4 for fewer frequencies than previous figures. Note that two electrode conditions (the MS and CA) were only run in one specimen (427L), and are excluded from further analysis. Given the similarities across electrodes, we do not expect results to differ from those shown. Transfer functions are shown superimposed over the range of responses observed in normal responses reported in the literature, as illustrated by light gray bands [44, 38]. Transfer functions to bone-conducted stimuli are shown in the lower panel. As in the individual example shown in Fig. 3, the population means show substantial overlap across the range of frequencies tested. Change from baseline seems present at low to middle frequencies in both SV and ST, although the difference appears to be greater in ST and overlap between conditions is substantial. Differential pressure appears somewhat higher for low to mid frequencies for acoustic stimulation, consistent with our prior report; no substantial differences are notable for bone conduction stimulation.

Figure 4.

Analysis of the responses across the population of specimens. The mean+/-SEM transfer functions across specimens, recorded under baseline (darkest lines) and CI electrode–inserted conditions (gray lines) for VStap (left), PSV (center), and PST (right) magnitudes. Responses are shown superimposed over dark gray bands representing the same range of responses shown in prior reports [44, 38]. Transfer functions to air-conducted and bone-conducted stimuli are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively.

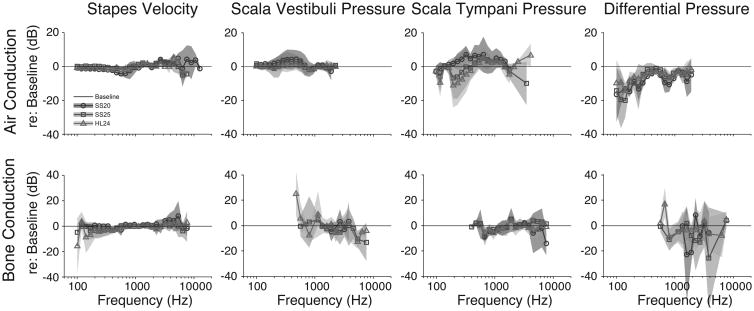

Intracochlear Pressure Changes with CI Insertion Relative to Baseline Measures

Differences between electrode conditions and baseline across all specimens tested were measured to facilitate comparisons across conditions (Figure 5 shows the mean+/-SEM). As in Fig .4, differences in Fig. 5 are calculated with respect to baseline for each specimen and at least two specimens with SNR greater than 3 dB are required for analysis.

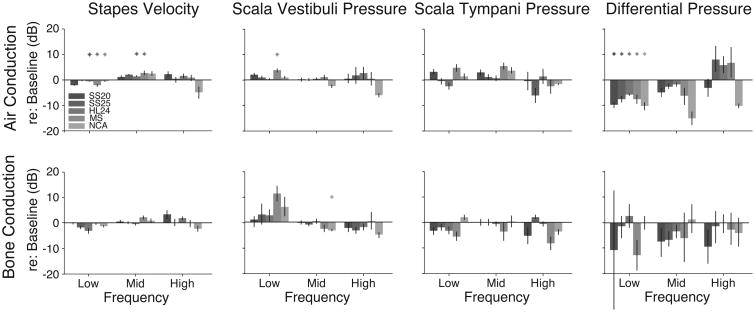

Figure 5.

The mean+/-SEM differences (in dB re :baseline) compared with baseline across all specimens tested. Nucleus Hybrid L24 (HL24), Nucleus CI422 Slim Straight inserted at 25mm (SS25), and Nucleus CI24RE Contour Advance (NCA). Differences in transfer functions re: baseline to air-conducted and bone-conducted stimuli are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively.

Quantitative comparisons of transfer function changes during electrode conditions compared with control are summarized in Figure 6. Responses were grouped into three frequency bands with low (f< 1 kHz), middle (1 kHz< f< 3 kHz), and high (f> 3 kHz) frequencies and roughly the same number of frequencies (∼3) within each band. Two-way analyses of variance were performed with response gain re: baseline as the dependent variable and electrode and frequency bands as independent variables for each measure and for each stimulation condition, assessed at a Bonferroni corrected α = 0.05 (0.00625 after correction). Results for air conduction stimulation reveal a significant main effect of frequency for VStap, PSV, and PDiff (F2,281 = 19.35, F2,208 = 6.28, F2,195 = 13.4; p ≪ 0.001, p = 0.0023, p ≪ 0.001), main effect of electrode for PST, and PDiff (F4,281 = 4.76, F2,208 = 8.45; p = 0.0011, p ≪ 0.001), and significant interactions for VStap (F8,281 = 6.2, p ≪ 0.001). Post-hoc testing with Tukey-Kramer honest significant difference (HSD) tests reveals significant differences between: low and high frequency bands for VStap and PDiff, and low and mid frequency bands for PSV. Additionally, post-hoc testing revealed Contour Advance was significantly different from each of the other electrodes with the largest changes in both PSV and PDiff. Results for bone conduction stimulation reveal a significant main effect of frequency for VStap and PSV (F2,231 = 5.3, F2,109 = 11.87; p = 0.0056, p ≪ 0.001), main effect of electrode for PST (F4,281 = 4.48; p = 0.0019), and no significant interactions. Post-hoc testing with Tukey-Kramer honest significant difference (HSD) tests reveals significant differences between: low and mid/high frequency bands for both VStap and PSV; mid-scala and most other electrodes for PST.

Figure 6.

Summary of the effects of inserting different CI electrodes with respect to the acoustic baseline. Responses were grouped within three frequency bands with low (f<1 kHz), middle (1 kHz<f<3 kHz), and high (f > 3 kHz) frequencies. Responses are shown as the average difference within each frequency band for each electrode condition. See the Results section for a description of the statistical analysis. Nucleus Hybrid L24 (HL24), Nucleus CI422 Slim Straight inserted at 20 and 25mm (SS20 and SS25), Nucleus CI24RE Contour Advance (NCA), and HiFocus Mid-Scala (MS). Differences in transfer functions re: baseline to air-conducted and bone-conducted stimuli are shown in the upper and lower panels, respectively.

To assess the change re: baseline, individual Bonferroni corrected t-tests (α = 0.05, 0.0017 after correction) were conducted on each electrode, for each frequency band, and for each condition. Conditions that were significantly different than zero (baseline) are marked with an asterisk in Fig 6.

Discussion

Electroacoustic stimulation (EAS) with hybrid implantation devices has become a new rehabilitative focus due to improved hearing outcomes in cochlear implant recipients with good low frequency residual hearing [1-8]. Despite emphasis on hearing preservation during cochlear implant surgery [27-31], some patients have demonstrated postoperative hearing loss in the low frequency range [2, 9-14], compromising their ability to utilize the benefits of EAS.

Possible causes of loss of residual hearing after CI electrode implantation

The cause of postoperative loss of residual hearing was previously attributed to cochlear trauma during electrode insertion [15-20], resulting in sensorineural changes. More recent data shows that a subset of patients with hearing loss after cochlear implantation have an audiometric air-bone-gap (ABG), suggesting the possibility of a conductive component to the postoperative change [12-14]. Proposed mechanisms for new or worsened ABG after CI include changes in middle or inner ear mechanics, damage to intracochlear structures, change in perilymph volume, and inflammatory reactions surrounding the electrode [15-26]. Despite various theories, the cause of postoperative loss of residual hearing remains elusive. The purpose of this investigation was to further characterize the nature of changes in hearing after the insertion of a CI electrode. Intracochlear pressures were measured to both air- and bone-conducted stimuli in order to assess for the contribution of a possible conductive component to postoperative loss of low-frequency residual hearing.

Previously, our laboratory investigated the effects of the presence of an implant electrode on intracochlear pressures and stapes velocity in cadaveric temporal bones [32]. With an electrode placed in the cochlea via the RW, measurements showed a small increase in scala tympani pressure and no change in scala vestibuli pressure. These changes, taken together, result in a decrease in differential pressure of about 5 dB and were similar to that found here. As the differential pressure represents a direct measure of the driving force of the basilar membrane, the Greene et al [32] study suggests that at least a small portion of the postoperative changes in hearing may be secondary to the presence of the electrode. However, stimuli for the previous study were presented via air conduction only, leaving the question regarding the presence of postoperative ABG incompletely answered.

Air-bone gap indicates a small conductive hearing loss with CI electrode implantation

In an effort to fill that knowledge gap, the current study specifically examined whether changes to intracochlear pressures seen previously with air-conducted stimuli were also present with bone-conducted stimuli. Our results indicated only a minimal effect on VStap and PSV, and small effects on PST and PDiff after CI electrode insertion with air-conducted stimuli. Consistent with previous results [32], this suggests the presence of the electrode can indeed account for 5-10 dB of loss in residual hearing. Since no significant differences in stapes velocities or intracochlear pressures were seen with bone-conducted stimuli following electrode insertion, the results suggest that the changes caused by the presence of the electrode alone affect acoustic but not bone conduction mechanisms. Additionally, since no changes in response to bone conduction were seen, it is unlikely that the conductive changes were due to a third window effect from the presence of the electrode in the round window [45]. As these findings were consistent across several different electrodes produced by different manufacturers, it can be inferred that a consistent mechanism underlies these small response changes despite differences between electrodes.

The mechanism of a new-onset ABG post-implantation has been widely debated, and contradicting studies support differing theories regarding the nature of postoperative hearing changes. Intraoperative measurements made in vivo to air-conducted stimuli before and after placement of a CI electrode in a study by Donnelly et al [17] revealed significant variability in stapes velocity. Though changes could support a mechanism for postoperative conductive changes, authors noted surgical variability (such as amount of perilymph lost during cochleostomy) that may confound conclusions. A similar in vivo study by Huber et al [18] using LDV to characterize RW velocity before and after implantation via cochleostomy showed only minimal changes (<3 dB), which was considered to be clinically insignificant. Preliminary data from a cadaveric temporal bone study using LDV by Pazen et al [19] also showed only slight changes to middle and inner ear transfer functions as calculated by RW and stapes velocities. Kiefer et al [20] developed a cochlear model suggesting that stiffening of the basilar membrane adjacent to an implanted electrode into the basal and middle cochlear turn did not affect movement in the low frequency area, thus predicting little impact on low-frequency acoustic sound transmission.

One hypothesis that our study is unable to replicate is the long-term effect of host response to the presence of the implant electrode. Inflammation and fibrosis secondary to the presence of a CI electrode has been seen across studies in post-mortem temporal bones with the focus of inflammatory response typically near the round window, though occasionally extending into lower frequency regions nearer to the apex [21-25]. Additionally, in vivo experimentation revealed stria vascularis capillary changes in guinea pigs after chronic stimulation with CI electrodes [46]. These inflammatory changes would likely increase the functional diameter and length of the implant electrode in terms of its presence causing changes in cochlear conduction, which would likely increase the magnitude of the effect on driving force seen in these results and in our previous study [32].

Choi and Oghalai [26] developed a mathematical model of passive cochlear mechanics in which the effect of scar tissue was simulated with dampening of inner ear structures. Computer simulation showed that basilar membrane velocity was reduced by increased damping, predicting that scar tissue formation around the implant electrode could theoretically lead to decreases in residual hearing. This evidence supports the discussion by Raveh et al [12], which suggests that these inner ear changes could affect air conduction more than bone conduction and result in an air-bone gap. While complete postoperative hearing loss or gradual loss of hearing over time following implantation are not addressed by our findings, patients with preserved hearing but increased thresholds likely have a conductive component from the presence of electrode that is contributing to postoperative hearing changes.

Conclusions

Preservation of residual hearing after cochlear implantation has gained importance as simultaneous electric-acoustic stimulation allows for improved outcomes in speech understanding, music appreciation, and localization [1-8]. Postoperative loss of residual hearing has previously been attributed to sensorineural changes; however, the presence of an increased postoperative air-bone gap observed in many patients, particularly in low frequencies (<1000 Hz), remains unexplained and could result in part from altered cochlear mechanics [12-14]. Although the etiology of hearing losses due to cochlear implantation remains unknown, our results here support the presence of at least a small conductive component in postoperative loss of residual hearing. Altered inner ear mechanics resulting from the presence of a CI electrode in the SV contribute about 5 dB, regardless of electrode length and configuration. This effect is primarily found in the low frequency range that is the target for hearing preservation in patients with residual hearing who may be able to utilize EAS. Larger changes in hearing after CI surgery are likely multifactorial and not due simply to the presence of the electrode in the cochlea alone.

Loss of residual hearing in cochlear implant patients was once considered an unavoidable side effect of surgery; now surgeons focus carefully on minimizing trauma to the neuroepithelium with soft techniques and specially designed electrode arrays [27-31]. The present investigation supports the continued research in minimizing electrode-induced trauma during surgery. In addition, our data suggests that at least a small, but not insignificant, component of changes in hearing after surgery is conductive in nature. As such, it is important to measure both air and bone conduction thresholds postoperatively and to consider conductive changes in the etiology of postoperative loss of residual hearing.

Acknowledgments

Funding: RMBH was funded by NIH NIDCD T32 DC-012280

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: Stephen P. Cass holds a position on the Cochlear Surgeon's Advisory Board at Cochlear Corporation.

References

- 1.Roland JT, Jr, Gantz BJ, Waltzman SB, Parkinson AJ The Multicenter Clinical Trial Group. United States multicenter clinical trial of the Cochlear Nucleus Hybrid implant system. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(1):175–81. doi: 10.1002/lary.25451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lenarz T, James C, Cuda D, Fitzgerald O'Connor A, Frachet B, Frijns JH, Klenzner T, Laszig R, Manrique M, Marx M, Merkus P, Mylanus EA, Offeciers E, Pesch J, Ramos-Macias A, Robier A, Sterkers O, Uziel A. European multi-centre study of the Nucleus Hybrid L24 cochlear implant. Int J Audiol. 2013 Dec;52(12):838–48. doi: 10.3109/14992027.2013.802032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gantz BJ, Turner CW. Combining acoustic and electrical hearing. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(10):1726–1730. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenarz T, Stover T, Buechner A, et al. Temporal bone results and hearing preservation with a new straight electrode. Audiol Neurootol. 2006;11(Suppl 1):34–41. doi: 10.1159/000095612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner CW, Gantz BJ, Vidal C, Behrens A, Henry BA. Speech recognition in noise for cochlear implant listeners: benefits of residual acoustic hearing. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115(4):1729–1735. doi: 10.1121/1.1687425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Ilberg C, Kiefer J, Tillein J, et al. Electric-acoustic stimulation of the auditory system. New technology for severe hearing loss. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1999;61(6):334–340. doi: 10.1159/000027695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorman MF, Gifford RH, Spahr AJ, McKarns SA. The benefits of combining acoustic and electric stimulation for the recognition of speech, voice and melodies. Audiol Neurootol. 2008;13(2):105–12. doi: 10.1159/000111782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gifford RH, Grantham DW, Sheffield SW, Davis TJ, Dwyer R, Dorman MF. Localization and interaural time difference (ITD) thresholds for cochlear implant recipients with preserved acoustic hearing in the implanted ear. Hear Res. 2014 Jun;312:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balkany TJ, Connell SS, Hodges AV, et al. Conservation of residual acoustic hearing after cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:1083–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000244355.34577.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James C, Albegger K, Battmer R, et al. Preservation of residual hearing with cochlear implantation: how and why. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:481–491. doi: 10.1080/00016480510026197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown RF, Hullar TE, Cadieux JH, Chole RA. Residual hearing preservation after pediatric cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2010 Oct;31(8):1221–6. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181f0c649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raveh E, Attias J, Nageris B, Kornreich L, Ulanovski D. Pattern of hearing loss following cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;272(9):2261–2266. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chole R, Hullar T, Potts L. Conductive component after cochlear implantation in patients with residual hearing conservation. Am J Audiol. 2014;23(4):359–364. doi: 10.1044/2014_AJA-14-0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattingly JK, Uhler KM, Cass SP. Air-Bone Gaps Contribute to Functional Hearing Preservation in Cochlear Implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001171. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eshraghi A. Prevention of cochlear implant electrode damage. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14(5):323–328. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000244189.74431.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eshraghi AA, Polak M, He J, Telischi FF, Balkany TJ, Van De Water TR. Pattern of hearing loss in a rat model of cochlear implantation trauma. Otol Neurotol. 2005 May;26(3):442–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000169791.53201.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly N, Bibas A, Jiang D, Bamiou DE, Santulli C, Jeronimidis G, Fitzgerald O'Connor A. Effect of cochlear implant electrode insertion on middle-ear function as measured by intra-operative laser Doppler vibrometry. J Laryngol Otol. 2009 Jul;123(7):723–9. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109004290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huber AM, Hoon SJ, Sharouz B, Daniel B, Albrecht E. The influence of a cochlear implant electrode on the mechanical function of the inner ear. Otol Neurotol. 2010 Apr;31(3):512–8. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181ca372b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pazen D, Nunning M, Anagiotos A, et al. The impact of a cochlear implant electrode array on middle ear transfer function: a temporal bone study. 13th International Conference on Cochlear Implants and Other Implantable Auditory Technologies; Munich, Germany. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiefer J, Bohnke F, Adunka O, Arnold W. Representation of acoustic signals in the human cochlea in presence of a cochlear implant electrode. Hear Res. 2006;221:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seyyedi M, Nadol J., Jr Intracochlear inflammatory response to cochlear implant electrodes in humans. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(9):1545–1551. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Leary SJ, Monksfield P, Kel G, Connolly T, Souter MA, Chang A, Marovic P, O'Leary JS, Richardson R, Eastwood H. Relations between cochlear histopathology and hearing loss in experimental cochlear implantation. Hear Res. 2013 Apr;298:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Somdas M, Li P, Whiten D, Eddington D, Nadol J., Jr Quantitative evaluation of new bone and fibrous tissue in the cochlea following cochlear implantation in the human. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12(5):277–284. doi: 10.1159/000103208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li PM, Somdas MA, Eddington DK, Nadol JB., Jr Analysis of intracochlear new bone and fibrous tissue formation in human subjects with cochlear implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007 Oct;116(10):731–8. doi: 10.1177/000348940711601004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nadol JB, Jr, Eddington DK. Histologic evaluation of the tissue seal and biologic response around cochlear implant electrodes in the human. Otol Neurotol. 2004 May;25(3):257–62. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi CH, Oghalai JS. Predicting the effect of post-implant cochlear fibrosis on residual hearing. Hear Res. 2005 Jul;205(1-2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Usami S, Moteki H, Suzuki N, et al. Achievement of hearing preservation in the presence of an electrode covering the residual hearing region. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131(4):405–412. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2010.539266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tamir S, Ferrary E, Borel S, et al. Hearing preservation after cochlear implantation using deeply inserted flex atraumatic electrode arrays. Audiol Neurootol. 2012;17:331–7. doi: 10.1159/000339894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Havenith S, Lammers MJ, Tange RA, Trabalzini F, della Volpe A, van der Heijden GJ, Grolman W. Hearing preservation surgery: cochleostomy or round window approach? A systematic review. Otol Neurotol. 2013 Jun;34(4):667–74. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318288643e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedland DR, Runge-Samuelson C. Soft cochlear implantation: rationale for the surgical approach. Trends Amplif. 2009 Jun;13(2):124–38. doi: 10.1177/1084713809336422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adunka O, Kiefer J, Unkelbach MH, Lehnert T, Gstoettner W. Development and evaluation of an improved cochlear implant electrode design for electric acoustic stimulation. Laryngoscope. 2004 Jul;114(7):1237–41. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greene NT, Mattingly JK, Jenkins HA, et al. Cochlear Implant Electrode Effect on Sound Energy Transfer Within the Cochlea During Acoustic Stimulation. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:1554–61. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattingly JK, Greene NT, Jenkins HA, et al. Effects of Skin Thickness on Cochlear Input Signal Using Transcutaneous Bone Conduction Implants. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36:1403–11. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devèze A, Koka K, Tringali S, et al. Active middle ear implant application in case of stapes fixation: a temporal bone study. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:1027–34. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181edb6d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lupo JE, Koka K, Jenkins HA, et al. Vibromechanical Assessment of Active Middle Ear Implant Stimulation in Simulated Middle Ear Effusion: A Temporal Bone Study. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:470–5. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318299aa37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tringali S, Koka K, Devèze A, et al. Round window membrane implantation with an active middle ear implant: a study of the effects on the performance of round window exposure and transducer tip diameter in human cadaveric temporal bones. Audiol Neurootol. 2010;15:291–302. doi: 10.1159/000283006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Devèze A, Koka K, Tringali S, Jenkins HA, Tollin DJ. Techniques to improve the efficiency of a middle ear implant: effect of different methods of coupling to the ossicular chain. Otol Neurotol. 2013 Jan;34(1):158–66. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182785261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakajima HH, Dong W, Olson ES, et al. Differential intracochlear sound pressure measurements in normal human temporal bones. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009;10:23–36. doi: 10.1007/s10162-008-0150-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olson ES. Observing middle and inner ear mechanics with novel intracochlear pressure sensors. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998 Jun;103(6):3445–63. doi: 10.1121/1.423083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olson ES. Direct measurement of intra-cochlear pressure waves. Nature. 1999;402:526–9. doi: 10.1038/990092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stenfelt S, Hato N, Goode RL. Round window membrane motion with air conduction and bone conduction stimulation. Hear Res. 2004;198:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stenfelt S, Hato N, Goode RL. Fluid volume displacement at the oval and round windows with air and bone conduction stimulation. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115:797–812. doi: 10.1121/1.1639903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tringali S, Koka K, Jenkins HA, Tollin DJ. Sound location modulation of electrocochleographic responses in chinchilla with single-sided deafness and fitted with an osseointegrated bone-conducting hearing prosthesis. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(4):678–686. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosowski JJ, Chien W, Ravicz ME, et al. Testing a method for quantifying the output of implantable middle ear hearing devices. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12:265–76. doi: 10.1159/000101474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Merchant SN, Rosowski JJ. Conductive Hearing Loss Caused by Third-Window Lesions of the Inner Ear. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Apr;29(3):282–9. doi: 10.1097/mao.0b013e318161ab24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reiss LA, Stark G, Nguyen-Huynh AT, Spear KA, Zhang H, Tanaka C, Li H. Morphological correlates of hearing loss after cochlear implantation and electro-acoustic stimulation in a hearing-impaired Guinea pig model. Hear Res. 2015 Sep;327:163–74. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]