Abstract

Cancer fatigue has been defined and described as an important problem. However, few studies have assessed the relative importance of fatigue compared with other patient symptoms and concerns. To explore this issue, the authors surveyed 534 patients and 91 physician experts from 5 NCCN member institutions and community support agencies. Specifically, they asked patients with advanced bladder, brain, breast, colorectal, head and neck, hepatobiliary/pancreatic, kidney, lung, ovarian, or prostate cancer or lymphoma about their “most important symptoms or concerns to monitor.” Across the entire sample, and individually for patients with 9 cancer types, fatigue emerged as the top-ranked symptom. Fatigue was also ranked most important among patients with 10 of 11 cancer types when asked to rank lists of common concerns. Patient fatigue ratings were most strongly associated with malaise (r = 0.50) and difficulties with activities of daily living, pain, and quality of life. Expert ratings of how much fatigue is attributable to disease versus treatment mostly suggested that both play an important role, with disease-related factors predominant in hepatobiliary and lung cancer, and treatment-related factors playing a stronger role in head and neck cancer.

Keywords: Advanced cancer, symptom management, assessment, fatigue

Fatigue is the most prevalent symptom associated with cancer and can have a broad impact on physical, emotional, and cognitive function.1–4 Depending on the patient sample and methodology used, prevalence of fatigue in patients with cancer is estimated to be between 60% and 90%.5,6 Fatigue tends to worsen with the progression of cancer and its, treatment, and can be one of the first indicators of the presence or recurrence of cancer.7

In advanced cancer and among long-term cancer survivors, fatigue is a commonly enduring symptom after chemotherapy or radiotherapy. How important fatigue is compared with the many other symptoms that people with cancer experience is less clear from the available literature.

Vogelzang et al.8 showed that fatigue is underrecognized and undertreated. In their survey, nearly 80% of patients experienced “a general feeling of debilitating tiredness or loss of energy” during their disease and treatment course, with nearly one third experiencing daily fatigue and the same percentage reporting adverse impact on their daily routines. Data from a parallel survey of oncologists suggested that physicians recognize that detection of fatigue can be improved.

This deficiency may be partly because of suboptimal communication regarding this symptom. Notably, half of the patients in this study did not discuss fatigue treatment options with their oncologists, and less than one third reported that their physicians recommended treatment for fatigue.

Recently reported results of a similar symptom-management survey showed that, although patients continue to have unmet communication needs related to fatigue, patients find these discussions extremely useful when they occur.9 Therefore, effective identification and management of fatigue may dramatically reduce its overall burden and improve quality of life4 among patients with cancer.10

Using questions from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system, Cella et al.11 polled expert physicians and nurses (N = 455) at 17 NCCN member institutions to obtain a set of brief, clinically relevant symptom indexes for 9 tumor sites (bladder, brain, breast, colorectal, head and neck, hepatobiliary/pancreas, lung, ovarian, and prostate). As part of the survey, each expert clinician iteratively rated the 5 most important symptoms to assess when evaluating drug treatment for advanced disease. Fatigue was nominated by physicians and nurses among the top 5 symptoms or concerns across all cancer types. In fact, fatigue emerged as the chief clinician-rated concern for 4 of the 9 tumor sites (breast, colorectal, ovarian, and prostate).

Given the varied prevalence estimates and clear functional impact of fatigue on patients’ lives, we sought to determine its relative importance using a method similar to that used with clinical experts.11 Specifically, we were interested in the importance ratings of fatigue compared with other symptoms and across 11 cancer types. Because cancer-related symptoms occur in a broader patient context, we also sought to determine what other symptoms were highly associated with patient-reported fatigue, and whether these ratings varied by sociodemographic variables or by disease severity. This approach may allow for more reliable disease comparisons and prioritization of treatment targets.

Method

Patient Eligibility and Recruitment

Patients were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age and had stage III or IV bladder, brain, breast, colorectal, head and neck, hepatobiliary/pancreatic, kidney, lung, ovarian, or prostate cancer or lymphoma. Patients could not have had any other primary malignancy in the previous 5 years, except non-melanoma skin cancer. In addition, patients must have had at least 2 cycles of chemotherapy (or 1 month of treatment with noncyclical chemotherapy).

Patients were recruited from a subset of NCCN member institutions and community support agencies. Specifically, participants were recruited from 5 NCCN member institutions, including Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center | Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center (Boston, MA), Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center (Durham, NC), Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (Seattle, WA), H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute (Tampa, FL), and Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University, Feinberg School of Medicine (Chicago, IL). Patients were also recruited through the Cancer Health Alliance of Metropolitan Chicago, a coalition of 4 community-based support agencies serving the metropolitan Chicago area.

Physician Eligibility and Recruitment

Physician input was solicited to assess which symptoms were considered to be disease- versus treatment-related. Physicians were eligible to participate if they were currently in practice and had at least 3 years’ experience treating a minimum of 100 patients with 1 of the 11 target diseases. NCCN staff or study staff at the 5 participating institutions recruited physicians from 20 NCCN member institutions through e-mail.

Procedures

Data for the present study come from a larger study12 that developed a series of patient-centered, tumor-specific, health-related quality of life (HRQL) indexes. Our focus in the present analyses was patients’ experience of the symptom of fatigue, which was assessed in 2 complementary ways.

In an open-response interview format, most patients (at least half of each cancer group) were first asked: “Please think of the full range of your experience receiving drug treatment for your illness. Please tell me what you think are the most important symptoms or concerns to monitor when assessing the value of drug treatment for your illness.” As a follow-up question, participants were asked: “Please tell me on a scale of 0–10 (with 0 being not important and 10 being extremely important) how important each symptom or concern is to you.” The open-response format allowed for patient input without potential priming effects of a preconstructed symptom list.

Next, patients were asked to review a symptom/concern checklist that contained, depending on cancer type, 23 to 40 items nominated by clinician experts and from the applicable FACT questionnaire. All checklists included the item, “Lack of energy (fatigue).” Furthermore, the hepatobiliary and kidney cancer checklists included the item, “Fatigue;” similarly, the lymphoma checklist added, “Feeling weak all over” and “Getting tired easily.”

The checklists were identical in structure to those administered to NCCN physicians and nurses in our previous study.11 To control for response bias due to order effect, 4 versions of each checklist were administered. Patients were first asked to select no more than 10 symptoms or concerns they believed were “the most important symptoms or concerns to monitor when assessing the value of drug treatment for advanced (specified) cancer.” Patients were then asked to select up to 5 of the 10 top-ranked concerns as “the very most important.” Space was provided for respondents to add symptoms or concerns that were not listed.

After providing symptom rankings, patients were asked to complete the appropriate cancer-specific FACT quality of life questionnaire. All questionnaires comprise the core FACT-General (FACT-G)13 questionnaire and the appropriate disease-specific subscale.

Eligible physicians were directed to a Web-based survey which asked them to rate all symptoms/concerns on a 5-point scale based on the degree to which the item was disease-related versus a treatment side effect. Physician respondents were also given the opportunity to rate symptoms as neither disease- nor treatment-related.

Results

Sample

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical status of enrolled participants (N = 534). Patients had a median age of 59 years (range, 24–88 years). At least 50 patients with each of 11 cancer types were recruited, except those with bladder cancer (n = 31). The sample was almost equally divided by gender (48.3% female) and was predominately Caucasian (88.9%) and well educated (49.0% with bachelor’s degree or higher). Approximately one fifth of patients reported normal activity without significant symptoms (performance status rating [PSR] = 0) and nearly half reported normal activity with some symptoms (PSR = 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Summary of Sample (n = 534)

| Age in years | ||

| M (SD) | 59.0 (11.9) | |

| Median (range) | 59 (24–88) | |

| n | % | |

| Female | 258 | 48.3 |

| Race/ethnicity (n = 1 missing) | ||

| White | 474 | 88.9 |

| African-American | 44 | 8.3 |

| Asian | 9 | 1.7 |

| Other | 6 | 1.1 |

| Education | ||

| < 12th grade | 34 | 6.4 |

| High school diploma or GED | 102 | 19.1 |

| Vocational school or some college | 136 | 25.5 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 154 | 28.8 |

| Professional or graduate degree | 108 | 20.2 |

| Current occupational status (n = 3 missing) | ||

| Homemaker | 45 | 8.5 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 2.1 |

| Retired | 192 | 36.2 |

| On disability | 114 | 21.5 |

| On leave of absence | 28 | 5.3 |

| Employed, full-time | 107 | 20.2 |

| Employed, part-time | 34 | 6.4 |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Bladder | 31 | 5.8 |

| Brain | 50 | 9.4 |

| Breast | 52 | 9.7 |

| Colorectal | 50 | 9.4 |

| Head and neck | 50 | 9.4 |

| Hepatobiliary | 50 | 9.4 |

| Kidney | 50 | 9.4 |

| Lung | 50 | 9.4 |

| Lymphoma | 50 | 9.4 |

| Ovarian | 51 | 9.6 |

| Prostate | 50 | 9.4 |

| Patient-rated ECOG Performance Status rating | ||

| 0, normal activities without symptoms | 122 | 22.8 |

| 1, some symptoms, but do not require bedrest during waking day | 258 | 48.3 |

| 2, require bedrest for less than 50% of waking day | 133 | 24.9 |

| 3, require bedrest for more than 50% of waking day | 21 | 3.9 |

Abbreviation: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

We also surveyed 91 physician experts. Although most provided input on a single cancer site, 15 provided input on 2 cancer sites, and 3 provided input on 3 sites. Physicians were predominately men (78%) with a mean (± SD) age of 47.1 (± 7.8) years. Nearly half (47.3%) of the experts had more than 15 years experience treating advanced cancer, across all sites. Furthermore, most physicians (62.6%) reported treating more than 500 patients with advanced disease.

Patient Ranking Data

Examination of the free-response data indicated that fatigue was the most commonly reported symptom for 9 of the 11 cancer types. For the remaining cancer types (breast and hepatobiliary), fatigue was reported as the second most important symptom or concern to monitor. Without prompting from a predetermined list, patients reported the importance of fatigue as a symptom to monitor when assessing the value of treatment.

Similar findings occurred when patients were given a comprehensive list of symptoms/concerns from which to select those considered most important. Fatigue was most commonly selected as a top 5 symptom/concern in all cancers, except among patients with head and neck cancer, who rated “Pain in my mouth, throat or neck” and “Being able to swallow naturally and easily” higher than fatigue (see Table 2 for other top-ranked symptoms/concerns). Fatigue was also ranked as the top concern within each performance status category. As seen in Table 2, the items “Lack of energy” and/or “Fatigue” were endorsed as chief concerns by 51.1% of the sample (range, 34.0% head and neck to 64.0% kidney).

Table 2.

Most Frequent Patient-Rated Top 5 Symptoms and Concerns Across 11 Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Symptom/Concern* | Cancer Type | Symptom/Concern* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | Lack of energy (fatigue): 48.4%† | Kidney | Lack of energy (fatigue): 64.0% |

| Worry condition will worsen | Side effects | ||

| Trouble meeting needs of family | Worry condition will worsen | ||

| Able to enjoy life | Able to enjoy life | ||

| Control bowels | Able to work | ||

| Brain | Lack of energy (fatigue): 44.0% | Lung | Lack of energy (fatigue): 44.0% |

| Frustrated unable to do things | Able to enjoy life | ||

| Able to enjoy life | Worry condition will worsen | ||

| Nausea | Able to sleep well | ||

| Seizures | Nausea | ||

| Breast | Lack of energy (fatigue): 57.7% | Lymphoma | Lack of energy (fatigue): 38.0% |

| Able to enjoy life | Getting tired easily | ||

| Able to work | Able to enjoy life | ||

| Worry condition will worsen | Worry about infections | ||

| Pain | Trouble concentrating | ||

| Colorectal | Lack of energy (fatigue): 62.0% | Ovarian | Lack of energy (fatigue): 60.8% |

| Able to enjoy life | Able to sleep well | ||

| Content with quality of life | Able to enjoy life | ||

| Nausea | Content with quality of life | ||

| Control bowels | Able to get around by self | ||

| Head and Neck | Pain in my mouth, throat, or neck | Prostate | Lack of energy (fatigue): 56.0% |

| Being able to swallow naturally/easily | Worry condition will worsen | ||

| Lack of energy (fatigue): 34.0% | Able to enjoy life | ||

| Nausea | Good appetite | ||

| Able to eat foods I like | Content with quality of life | ||

| Hepatobiliary | Lack of energy (fatigue): 52.0% | ||

| Worry condition will worsen | |||

| Able to enjoy life | |||

| Nausea | |||

| Able to do usual activities |

Listed symptoms/concerns are rank-ordered according to the frequency patients rated each as one of their top 5 concerns.

Percentages represent proportion of sample that ranked fatigue in their top 5 symptoms/concerns. For the entire sample (N = 534), 51.1% ranked fatigue among their top concerns. Fatigue was the top-ranked symptom within each performance status category.

Rating Data

We investigated the association of responses to the item, “I have a lack of energy” with sociodemographic and clinical variables. No significant association between fatigue ratings and age, gender, ethnicity, or education was found. The significant statistic (χ2 = 19.55; P < .005) for the association of current occupational status with fatigue ratings suggests that patients on disability or leave were more likely than employed participants to report severe fatigue (Table 3). Similar patterns emerged when these associations were examined within separate disease groups. Although no association was seen between cancer type and fatigue rating, fatigue was worse for more severe patient-rated performance status14 (χ2 > 100; P < .0001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Fatigue with Occupational and Performance Status

| “I Have a Lack of Energy” | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Not at All % |

A Little Bit % |

Somewhat % |

Quite a Bit % |

Very Much % |

|

| Current Occupational Status*† | ||||||

| Homemaker | 45 | 11.1 | 28.9 | 42.2 | 8.9 | 8.9 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 0.0 |

| Retired | 192 | 12.0 | 20.3 | 30.2 | 27.6 | 9.9 |

| On disability | 114 | 3.5 | 21.0 | 34.2 | 26.3 | 14.9 |

| On leave of absence | 28 | 0.0 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 25.0 | 17.9 |

| Employed, full-time | 107 | 15.9 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 16.8 | 9.4 |

| Employed, part-time | 33 | 12.1 | 42.4 | 27.3 | 6.1 | 12.1 |

| Patient-Rated ECOG Performance Status Ratingठ| ||||||

| 0, normal activity | 122 | 31.2 | 37.7 | 21.3 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| 1, some symptoms | 258 | 5.4 | 26.7 | 38.4 | 23.6 | 5.8 |

| 2, < 50% bedrest | 133 | 1.5 | 9.8 | 31.6 | 36.1 | 21.0 |

| 3, > 50% bedrest | 20 | 0.0 | 25.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 | 50.0 |

Occupational status data not available for 4 patients.

Occupational status significantly associated with fatigue ratings (χ2 = 19.55; P = .003).

ECOG performance status rating data not available for 1 patient.

Fatigue ratings are significantly associated with patient-rated ECOG performance status rating (χ2 = 180.32; P < .0001).

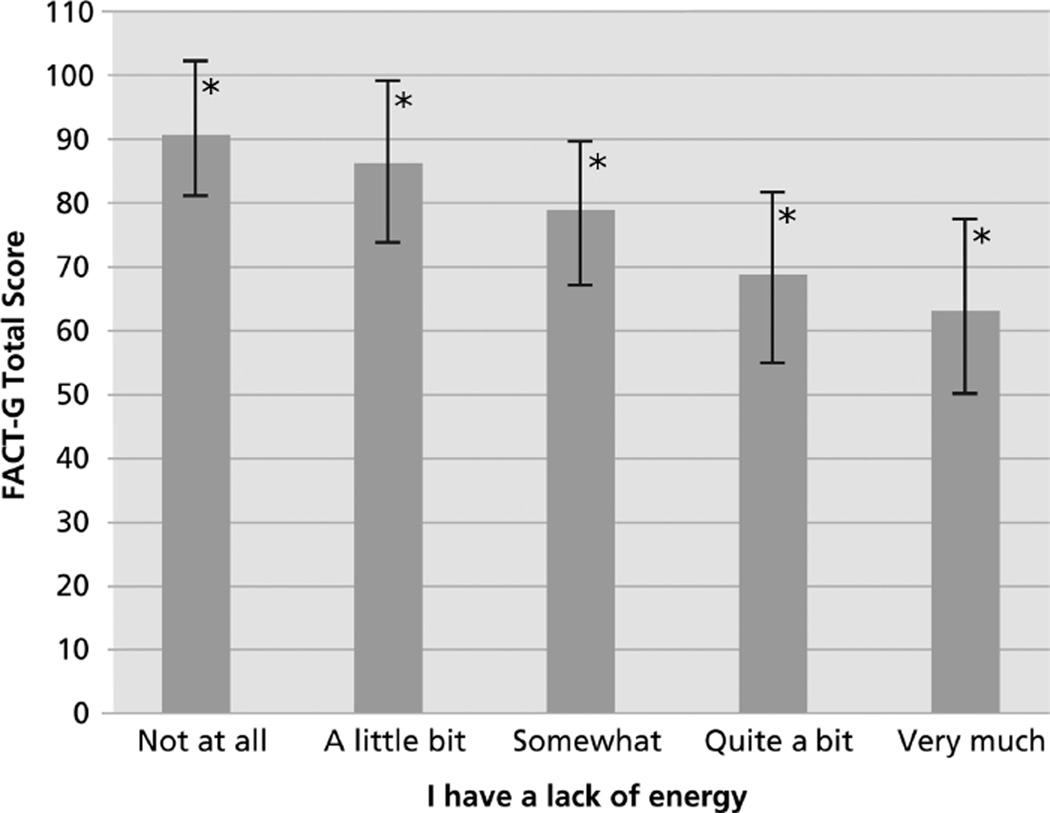

Table 4 lists the symptoms/concerns from the FACT-G that were most highly correlated with the item worded, “I have a lack of energy (fatigue)” (Figure 1). Among the overall patient sample, fatigue ratings were associated most strongly (r = 0.50; range, 0.23–0.67 by cancer type) with the item assessing malaise (“I feel ill”). Other symptoms/concerns that correlated highly with fatigue include those related to familial roles, spending time in bed, enjoying usual activities, and overall quality of life.

Table 4.

Top 10 Correlations: Association of Fatigue* With Other Functional Assessments of Cancer Therapy–General Symptoms/Concerns

| n | Spearman Correlation in Total Sample (Range for Disease Groups)† |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel ill | 530 | 0.50 (0.23 to 0.67) |

| 2. Because of my physical condition, I have trouble meeting the needs of my family | 533 | 0.48 (0.24 to 0.61) |

| 3. I am forced to spend time in bed | 532 | 0.46 (0.31 to 0.60) |

| 4. I am enjoying the things I usually do for fun | 532 | −0.45 (−0.20 to −0.63) |

| 5. I am content with the quality of my life right now | 532 | −0.44 (−0.26 to −0.60) |

| 6. I am bothered by side effects of treatment | 532 | 0.44 (0.35 to 0.61) |

| 7. I am able to work (include work at home) | 531 | −0.44 (−0.17 to −0.57) |

| 8. I have pain | 531 | 0.38 (0.04 to 0.58) |

| 9. I am able to enjoy life | 532 | −0.37 (−0.20 to −0.70) |

| 10. My work (include work at home) is fulfilling | 528 | −0.35 (−0.13 to −0.53) |

Fatigue item was worded: “I have a lack of energy.”

All correlations statistically significant in total sample (P < .0001).

Figure 1.

Overall quality of life as a function of fatigue ratings (n = 533). Greater levels of fatigue were associated with worse overall health-related quality of life (F[4, 524] = 70.88; P < .0001).

*Bars represent means ± 1 SD.

Abbreviation: FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General.

Table 4 also lists the sample-wide correlations and the ranges among disease groups. Considering the additional items that were administered to at least 100 patients (i.e., at least 2 disease groups), the strongest correlations with fatigue were observed with “I have been short of breath” (n = 253; r = 0.47) and “I have a good appetite” (n = 329; r = –0.43). Fatigue ratings were also associated with general quality of life. Specifically, greater levels of fatigue were associated with worse overall HRQL, as measured by the FACT-G (F[4, 524] = 70.88, P < .0001).

Physician ratings as to whether fatigue is primarily disease- or treatment-related differed among diseases (Table 5). More than half of physicians surveyed considered fatigue predominately disease-related for lung and hepatobiliary cancer; predominately or exclusively treatment-related for head and neck cancer; and too close to discriminate for lymphoma, colorectal, bladder, breast, and kidney cancer.

Table 5.

Physician Ratings (N = 91) as to Whether Fatigue Is Disease- or Treatment-Related

| “I Have a Lack of Energy” | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Type* | Predominately Disease-Related (%) |

Too Close to Determine (%) |

Predominately Treatment-Related (%) |

Exclusively Treatment-Related† (%) |

Neither Disease- nor Treatment-Related (%) |

| Bladder (n = 10) | 0 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Brain (n = 10) | 30 | 20 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Breast (n = 10) | 0 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Colorectal (n = 10) | 10 | 70 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Head and neck (n = 11) | 0 | 27 | 64 | 9 | 0 |

| Hepatobiliary (n = 10) | 80 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kidney (n = 10) | 30 | 60 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Lung (n = 10) | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphoma (n = 10) | 20 | 60 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Ovarian (n = 10) | 10 | 40 | 50 | 0 | 0 |

| Prostate (n = 11) | 45 | 36 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

Most experts provided input on a single cancer; however, 15 experts provided input on 2 cancer sites and 3 experts provided input on 3.

No clinicians rated fatigue as “exclusively disease-related.”

Discussion

When chosen from a comprehensive list of options, the most frequently ranked top 5 symptom/concern among advanced patients across 11 cancer types in the present sample was fatigue. The one exception occurred among patients with head and neck cancer; although these patients ranked fatigue as their top concern (with nausea) in the free-response query, they rated symptoms associated with pain and difficulty swallowing as more salient when presented with a list of symptoms/concerns.

These results are consistent with those of our earlier study, in which clinicians selected fatigue as one of the top 5 patients symptoms or concerns across all cancer types.11 In fact, fatigue emerged as the chief clinician-rated concern for 4 (breast, colorectal, ovarian, and prostate) of the 9 tumor sites considered in that study. Although the results of the present study and previous report are not directly comparable, the results from this study may indicate an increased awareness of the problem of fatigue since the original study by Vogelzang et al.8

In the present sample, fatigue ratings were not associated with age, gender, ethnicity, education, or cancer type. Although detail was not available on treatment regimens, fatigue ratings (and rankings) may vary as a function of treatment received. To a certain extent, cancer type may serve as a proxy for treatment regimen; however, future research on symptom priorities should consider the impact of specific treatments.

Furthermore, the single item used to assess fatigue may not discriminate well between groups. Notably, fatigue ratings were differentially associated with occupational and performance status. Responses to the item, “I have a lack of energy (fatigue)” were also significantly associated with several other symptoms (Table 4). Although no differences were detected in fatigue across sociodemographic variables, the single item seems to be sensitive to important clinical variables.

Across a diagnostically diverse sample of patients, fatigue is associated with activities of daily living and overall HRQL. Expert clinicians in the present study reported that most cancer-related fatigue was either treatment-related or both disease- and treatment-related with the exception of hepatobiliary cancers. These findings suggest that optimal detection of cancer-related fatigue may lead to improved interventions, which may then lead to improved daily functioning and reduced fatigue-related disability. This study is the first to systematically assess the relative importance of fatigue across a diverse sample of patients with advanced cancer, and therefore presents an important conceptual extension of our previous survey of physicians and nurses.

However, this study has some limitations. Fatigue was assessed using a single item. It is an empiric question whether the item used in the present study optimally detects diagnosable cancer-related fatigue. Furthermore, patients in the present sample were restricted to stage III and IV disease. Symptom priorities among patients with less-advanced disease may be different from those of patients in the current study. However, although stage of disease was restricted, a fairly wide range of performance status ratings were seen, suggesting that the present findings may generalize across levels of impairment seen in patients with advanced cancer. Additional research on symptom priorities will help guide oncology care and improve quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was funded by Ortho Biotech Clinical Affairs, LLC. The study from which the results were drawn was designed and conducted by independent investigators at Evanston Northwestern Healthcare and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Support for the study was provided by grants from the following pharmaceutical companies: Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centocor, Cell Therapeutics, Inc., Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck & Co., Novartis, Ortho Biotech, Pfizer, sanofi-aventis, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Portions of these findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

References

- 1.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winningham ML, Nail LM, Burke MB, et al. Fatigue and the cancer experience: the state of the knowledge. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994;21:23–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella D. Quality of life in cancer patients experiencing fatigue and anemia. Anemia in Oncology. 1998:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner LI, Cella D. Fatigue and cancer: causes, prevalence and treatment approaches. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:822–828. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irvine D, Vincent L, Graydon JE, et al. The prevalence and correlates of fatigue in patients receiving treatment with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. A comparison with the fatigue experienced by healthy individuals. Cancer Nurs. 1994;17:367–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prue G, Rankin J, Allen J, et al. Cancer-related fatigue: a critical appraisal. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:846–863. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg DB. Fatigue. In: Holland J, editor. Psycho-Oncology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelzang NJ, Breitbart W, Cella D, et al. Patient, caregiver, and oncologist perceptions of cancer-related fatigue: results of a tripart assessment survey. The Fatigue Coalition. Semin Hematol. 1997;34(3 Suppl 2):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, et al. Longitudinal screening and management of fatigue, pain, and emotional distress associated with cancer therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Roenn JH, Paice JA. Control of common, non-pain cancer symptoms. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:200–210. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cella D, Paul D, Yount S, et al. What are the most important symptom targets when treating advanced cancer? A survey of providers in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Cancer Invest. 2003;21:526–535. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120022366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosenbloom SK, Yount SE, Yost KJ, et al. Development and validation of eleven symptom indices to evaluate response to chemotherapy for advanced cancer: measurement compliance with regulatory demands. In: Farquhar I, Summers K, Sorkin A, editors. The Value of Innovation: Impacts on Health, Life Quality, and Regulatory Research. Oxford: Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Leslie WT, et al. Quality of life and nutritional wellbeing: measurement and relationship. Oncology. 1993;7(Suppl):105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]