Abstract

The outcome of an inflammatory incident can hang in the balance between restoring health and tissue integrity on the one hand, and promoting aberrant tissue homeostasis and adverse outcomes on the other. Both microbial-related and sterile inflammation is a complex response characterized by a range of innate immune cell types, which produce and respond to cytokine mediators and other inflammatory signals. In turn, cells native to the tissue in question can sense these mediators and respond by migrating, proliferating and regenerating the tissue. In this review we will discuss how the specific outcomes of inflammatory incidents are affected by the direct regulation of stem cells and cellular plasticity. While less well appreciated than the effects of inflammatory signals on immune cells and other differentiated cells, the effects are crucial in understanding inflammation and appropriately managing therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: inflammation, stem cells, stemness, stem cells and sterile inflammation, stem cells and microbes

Introduction

Inflammation has a well-established role in the defense of organisms against microbial invasion. The presence of commensal and pathogenic microbes, both intracellular and extracellular, is usually detected by receptors residing mostly in the surface of innate immune cells known as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). These receptors are the first line of the surveillance system which ultimately recognizes pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and triggers the inflammatory response. Acute and chronic inflammation in a number of diseases associated with pathogens and the interplay between infection and inflammation is of paramount importance to clinical outcomes (Apidianakis and Ferrandon, 2014).

While inflammation is a defense against pathogens it can also be triggered during processes unrelated to microbial insult. This process, termed sterile inflammation, is typically linked to chemical or physical triggers. Inflammatory cells present at the site of the damage recognize danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and secrete molecules which prime the tissue restoration via the proliferation of quiescent adult stem cells (Nagaoka et al., 2000; Koh and DiPietro, 2011; Petrie et al., 2014; Kizil et al., 2015). Sterile inflammation can have profound effects on tissue homeostasis and repair, for example during wound healing, or during the onset and initiation of inflammatory diseases.

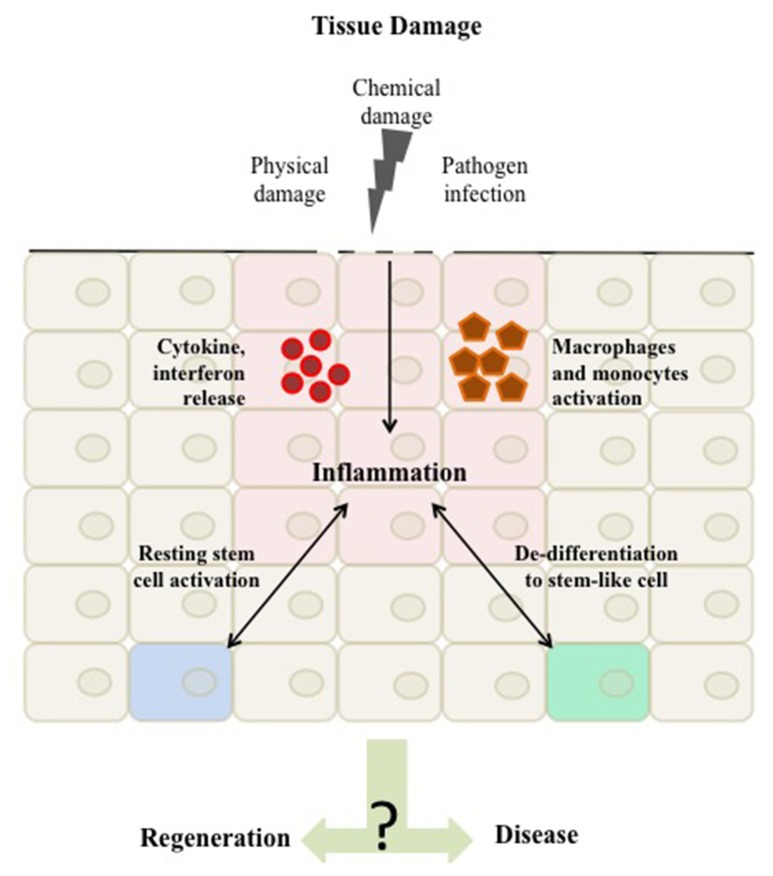

We summarize here evidence for the direct crosstalk between the inflammatory response and stem cells both in cases of microbial and sterile induced inflammation (Figure 1). Inflammation is emerging as an important regulator of stem cells and plays an intricate role in health and disease.

Figure 1.

Tissue damage can arise as a result of physical damage, chemical damage or pathogen infection. Once the damage is detected a homeostatic inflammatory response is activated to regenerate the tissue. This inflammation is characterized by the activation of immune cells, such as macrophages and monocytes and the release of inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and interferons to the site of damage. These mediators in turn can affect native tissue cells to respond by migrating and proliferating resulting in tissue repair. Evidence suggest that the inflammatory response acts as a regulator of tissue stemness either by directly affecting tissue stem cells or by shifting differentiated cells toward a stem-like cell character. The balance in this inflammatory response and its mediated stemness is a critical driver of either maintaining tissue integrity or promoting aberrant homeostasis and disease.

Regulation of stem cells in response to microbial motifs

Recently PRRs were shown to be expressed in the surface of tissue stem cells suggesting that there is the potential for direct effects of PAMPs on stem cell behavior (Boiko and Borghesi, 2012). For example, hematopoietic stem cells express toll-like receptors (TLRs) whose activation leads to the differentiation of myeloid progenitors into monocytes and macrophages immune cells (Nagai et al., 2006) as seen in the presence of the vaccinia virus in the bone marrow (Singh et al., 2008). Stem cells of solid tissues, more prominently the gut, have also been shown to express PRRs integrating inflammation to immune clearance and subsequent tissue regeneration. Intestinal stem cells (ISCs) expressing TLR4 show increased proliferation and expansion of the stem cell population in the intestinal epithelium (Santaolalla et al., 2013). ISCs have also been shown to express Nod2, a general sensor for peptidoglycan (Girardin et al., 2003). The constitutive expression of Nod2, in ISCs, provides protection against stress (Nigro et al., 2014). The ability of gut stem cells to respond directly to patterns, such as LPS (via TLR4) and peptidoglycan (via Nod2), may underlie mechanisms of tissue response not only to pathogenic bacteria but also commensals and is likely important to general tissue homeostasis via the interaction with intestinal microbiota. The findings in mammalian systems are corroborated by extensive literature in other experimental systems, such as Drosophila (Panayidou and Apidianakis, 2013).

Once an inflammatory program has already been initiated the production of cytokines, interferons etc. by local immune populations can further impact the behavior of stem cells. In the gut, innate lymphoid cells produce interleukin-22, a potent survival factor, which can directly act on ISCs promoting growth and epithelial regeneration (Lindemans et al., 2015). Chronic HBV infection also stimulates release of interleukin-22 by inflammatory cells, inducing proliferation of liver stem cells (Feng et al., 2012). In addition, the mediator of inflammation TNF-α is activated as a result of brain inflammation in neural stem cells seen in conditions of trauma, multiple sclerosis and pathogen infections. TNF-α activation ultimately brings about proliferation of the neural stem cells (Widera et al., 2006). Neural stem cells in the hippocampus have also been shown by in vivo studies to proliferate upon the presence of bacterial enterotoxins (Wolf et al., 2009). In the urinary tract, upon E. coli infection, the uroepithelial stem cells are activated for epithelial renewal in response to the inflammatory response (Mysorekar et al., 2009).

The presence of pathogenic burden in the hematopoietic system rapidly depletes immune cells stimulating intermediate blood progenitors to maintain blood cell balance (Hawkins et al., 2006). Inflammation-induced myelopoiesis, due to pathogen presence, results in the release of interleukin-27 causing activation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Furusawa et al., 2016). Chronic infection, as seen in the presence of the Mycobacterium avium, results in the activation of quiescent HSCs through the release of the inflammatory mediator interferon-γ (Baldridge et al., 2010).

Inflammation is proposed to promote tissue recovery via its effects on differentiated cells to regenerate the tissue (Karin and Clevers, 2016). In some cases the differentiated cells de-differentiate in response to inflammation, acquiring stem-like characteristics and increased cellular plasticity. In support of this idea, the induction of immunity was found to be required for efficient nuclear reprogramming in vitro (Lee et al., 2012).

Tissue reprogramming is achieved through the upregulation of growth factors and cytokines in the inflammatory microenvironment (Grivennikov et al., 2010). This could be attributed to changes in the expression of specific genes/pathways which shift a differentiated cell closer toward a stem cell character. Alternatively, the effects could impart tissue stem cells or progenitors with increased/altered capabilities.

There are a number of examples to support the idea that inflammation caused by infections leads to tissue regeneration and/or cellular stemness. Such a response has been observed in viral infections of HBV and HCV where inflammation in the liver induced expression of stemness markers (Karakasiliotis and Mavromara, 2015). Specifically, the secretion of interleukin 6 (IL6) by the inflammatory cells during HBV infection regulates the expression of Oct4 and Nanog pluripotency factors (Chang et al., 2015). Furthermore, the hypoxia factor HIF-1α produced in the HCV virally-infected cells confers an epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) character (Wilson et al., 2012). It is important to note that in this case, the EMT is accompanied by enhanced viral replication.

In fact, inflammation-mediated changes on the differentiation status of the tissue are a factor in the pathology which accompanies disease. Persistent induction of stemness in the infected tissue in the presence of chronic inflammation, as seen in infections of the gut, can likely contribute to carcinogenesis (Apidianakis and Ferrandon, 2014; Kuo et al., 2016). However, emerging concept suggests that it may also be beneficial to the pathogen. Several groups have shown that for some infectious agents it can play a role during their replication (as in the case of HBV and HCV), their dissemination, and protection (Masaki et al., 2013; Nigro et al., 2014; Karakasiliotis and Mavromara, 2015). A more prominent example, the leprosy bacterium infects preferentially Schwann cells of the nervous system and induces their reprogramming into stem-like cells. The infected stem-like cells then migrate to the mesenchyme where they re-differentiate to mesenchyme tissue allowing for expansion of the infection (Masaki et al., 2013). The innate immune response has been shown to precede this reprogramming (Masaki et al., 2014). For efficient dissemination, the cells need to evade the host immunity and they do so by inducing an inflammatory response achieved through the release of factors from the stem-like cells. This subsequently recruits macrophages that form granulomas able to bypass immunity and migrate.

The inflammatory response is important to the host organism as a protective mechanism against pathogen invasion as well as tissue regeneration through the induction of stemness. In some cases however, through inflammation, pathogens are able to escape immune surveillance for their protection and dissemination with possible consequences to their lifecycle and replicative potential, as we have seen in the cases of the HBV and HCV viruses or of bacteria in the intestine or the nervous system.

Regulation of stem cells during tissue (re)generation

Sterile inflammation has also been shown to lead to profound changes in the differentiation status of the tissue. An example is the regenerative process which takes place in response to wound healing. Wound healing requires an ordered sequence of events ranging from acute inflammation, tissue organization, and remodeling (Gurtner et al., 2008; Karin and Clevers, 2016). However, the period of tissue repair varies between the extent of the damage and the site of the damaged tissue (Meyer et al., 1992; Gordon et al., 2003; Pitsouli et al., 2009).

Tissue repair following an insult restores health in the tissue and preserves the state of homeostasis. Regeneration in the tissue is achieved via the priming of resident slow-cycling stem cells to adopt a proliferative state and yield transit-amplifying cells which will differentiate to restore tissue architecture. Sterile inflammation plays an important role in this process in ways which are likely distinct to those seen during infection (Bezbradica et al., 2016).

The intestine can regenerate very rapidly. Tissue restoration is mediated via neutrophil infiltration at the site of the damage. These are responsible for JNK activation and the priming and proliferation of slow–cycling ISCs (Karin and Clevers, 2016). Work from Riehl et al. (2000) further supported the role of inflammatory signals, as administration of inflammatory cytokines and growth factors following radiation exposure rescued damaged epithelium via the proliferation and differentiation of intestinal stem cells (Riehl et al., 2000). However, homeostasis is sustained via the activation of developmental and inflammatory pathways which activate dormant ISCs. For instance, JNK signaling pathway is responsible for the secretion of IL6 which activates the JAK-STAT pathways leading to ISC proliferation (Jiang et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2010; Kuhn et al., 2014).

In the case of the skin epithelium, which also encounters frequent damage, it is proposed that keratinocytes trigger the inflammatory phase of the wound healing by secreting molecules like IL6 and TNFα (Wang et al., 2004; Ryser et al., 2014; Rittié, 2016). These inflammatory molecules along with other developmental mediators, such as extracellular matrix components (Kurbet et al., 2016) signal to the niche of slow-cycling adult stem cells in order to train them toward proliferation and ultimate differentiation (Cotsarelis et al., 1990; Taylor et al., 2000).

Another organ that has a fast-paced regeneration with the ability to recover its mass even after substantial loss is the liver (Michalopoulos, 2007). While it remains controversial whether the adult liver depends on a stem cell population during homeostatic conditions, various stem cell or progenitor populations have been described to participate in its regeneration following injury (Yimlamai et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Soon after partial hepatectomy, the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL6 are upregulated at the site of regeneration guiding hepatocytes to enter mitosis and restore lost tissue. Beyond the involvement of unipotent mature hepatocytes, which assist in the repair process of the liver particularly in response to acute inflammation, liver progenitor cells are also present to mediate liver repair. This is typically the case in the context of chronic inflammation, when mature hepatocytes have reached their replicative limit (Viebahn and Yeoh, 2008; Español-Suñer et al., 2012). While some controversy exists with regard to the exact characteristics of liver progenitors (Dollé et al., 2010), they respond to inflammatory signals following injury to generate differentiated cells essential for liver regeneration.

Our understanding of the effects of inflammatory signaling on stem cells, stems mostly from model tissue systems, such as the intestine, skin and liver. However, the inflammatory signaling to resident tissue stem cells is corroborated as crucial to regeneration in more poorly understood tissues and non-mammalian model systems as well (Apidianakis and Rahme, 2011). In mice, the recently described dclk1 progenitors have been shown to respond to inflammation during pancreatic regeneration (Westphalen et al., 2016). There is also extensive work implicating crosstalk between neural stem cells and inflammation in mammals and zebrafish (Kizil et al., 2015). Specifically, during zebrafish brain regeneration, inflammation is the trigger which initiates neural stem cell proliferation (Kyritsis et al., 2012).

While inflammation can prime stem cell responses it is becoming increasingly clear that in certain contexts stem cells possess immunomodulatory potential. Mesenchymal stem cells and neural stem cells are the two cell types most often ascribed with immunomodulatory potential (Kizil et al., 2015; Le Blanc and Davies, 2015). In both these examples stem cells have been shown to dampen or alter inflammation with beneficial outcomes in inflammation-associated disease. Despite the fact that the mechanisms are still poorly understood there is justified excitement for the potential application of these properties in therapeutics.

The crosstalk between sterile inflammation and stem cell plasticity within a tissue during the wound healing response is a critical step in the regenerative process. Priming stem cells that reside in the circulation, in addition to the stem cells of the regenerating tissue, may also contribute to this process. HSCs are likely directed to liver and skin following physical damage (Rennert et al., 2012). It was further suggested that inflammatory cytokines and growth factors released due to tissue injuries can stimulate a signaling wave toward bone marrow-residing stem cells to enter the circulation and inhabit the injured site. These bone-marrow stem cells and locally residing tissue stem cells hold the capacity of tissue regeneration. Perhaps more surprisingly, sterile inflammatory signaling, such as that initiated by IFNγ and TLR4, plays a role not only in the regeneration of adult tissue but is a well-conserved regulator in their production during development (Li et al., 2014; He et al., 2015). These findings certainly reframe currently held ideas about the evolutionary function of inflammation.

Inflammatory signaling during disease

In some cases inflammation, particularly where it is chronic, can lead to the development of disease. The continuous and often aberrant response of stem cells as a result of this signaling has been shown to play an important part in this process. Intestinal stem cells express TLR4 the activation of which can lead to ER-stress, a trigger for stem cell apoptosis during necrotizing enterocolitis (Afrazi et al., 2014). In Barrett's esophagus Lgr5+ gastric cardia stem cells can migrate in response to the inflammatory signaling and are the likely source of the metaplastic and dysplastic cells observed in the course of the disease (Quante et al., 2012).

The disease most commonly associated with inflammation is of course cancer. Multiple studies have produced substantial evidence suggesting that cancer and inflammation are in many cases connected, interdependent biological processes (Coussens and Werb, 2002; Balkwill et al., 2005; Karin, 2006). This is true in cases where the cancer is associated with microbial or viral causes, but also in cases where no pathogen is directly linked. For example, in addition to their mutagenic effects, carcinogens in tobacco smoke cause damage and chronic inflammation to the lungs and increase the risk of cancer development (Punturieri et al., 2009). Autoimmunity is also associated with increased tumor development. The chance of developing colitis-associated cancer or lymphoma is increased in people suffering from inflammatory bowel or celiac disease, respectively (Kraus and Arber, 2009; Waldner and Neurath, 2009).

The important bidirectional link between inflammation and stem cells has direct implications on cancer development. Studies have suggested that HSC recruitment and differentiation is directly linked to increased inflammation. For example, CD34+ progenitor cells are recruited to sites with increased inflammation, probably using the same adhesion and chemokine receptors used for stem cell homing to the bone marrow (PSGL-1, CXCL12, α4β1 integrin, CD44, and others) (Blanchet and McNagny, 2009). Inflammatory mediators seem to have a vital role in inducing expression of stemness-related genes. The expression of stemness-related genes in cancer is likely linked to the generation and evolution of the compartment of cells able to regenerate tumor diversity, the cancer stem cells (CSCs) (Kuo et al., 2016; Uthaya Kumar et al., 2016). Upregulation of OCT4 has been shown to contribute to tumor cell migration and resistance to cancer therapeutics (Ma et al., 2011; Chang et al., 2015, 2016; Bhatt et al., 2016).

While inflammation is one of the stimuli suggested to initiate such transcriptional changes, once CSCs form, evidence suggests that they can serve to further amplify inflammatory signaling. Chemoresistant CSCs were found to express proinflammatory gene signatures, mainly due to the sustained activation of NF-kB and interferon-stimulated regulatory element (ISRE)-dependent pathways. Notably, tumor-associated macrophages in this environment protect tumor cells from chemotherapeutic agents by promoting and enhancing the tumor growth properties of CSCs (Jinushi et al., 2011). A proinflammatory signature has also been exhibited by leukemia stem cells which can promote chemoresistance by means of metabolic adaptation (Ye et al., 2016). Thus, in some cases, tumors respond to chemotherapy by altering the immunological profile of the microenvironment in part due to the direct action of CSCs, thus further enabling tumor growth (Jinushi et al., 2011; Jinushi, 2014).

In more rare cases recruited circulating stem cells, subjected to chronic inflammation in a tissue, have been proposed to act as cancer-initiating cells themselves. Houghton et al. (2004), used a mouse model to demonstrate an extremely important connection between chronic inflammation, hematopoietic stem-cell recruitment and cancer development at the site of inflammation (Houghton et al., 2004). In this study, infection by Helicobacter pylori in the mouse caused the recruitment and subsequent engraftment of bone marrow derived stem cells (BMDC) into the stem cell compartment of the gastric mucosa. Within their new, inflamed niche, these engrafted stem cells accumulated mutations, and eventually gave rise to gastric tumors. This study showcased a direct connection between chronic inflammation, stem cell recruitment and increased cancer development (Houghton et al., 2004).

Conclusion

Inflammatory signaling promotes cellular responses with critical ramifications during infection, tissue generation/regeneration, cancer and other diseases. We summarize here work which demonstrates that stem cells can respond to and participate in inflammatory cascades in a direct manner. They express receptors which detect PAMPs and DAMPs, the initial triggers of the inflammatory response. They are able to mobilize and proliferate in response to inflammation in addition to producing cytokines which further amplify the response. Accumulating evidence suggests that in cases where a pathogen is involved, the changes in stemness mediated by inflammation also have a profound influence on the lifecycle of the pathogen. This is an area which merits further research. Understanding the crosstalk between stem cells and inflammation is an important piece of the puzzle which refines our understanding of the evolutionary roles of inflammation. Furthermore, it provides indispensable tools in our quest to harness knowledge into useful therapeutics.

Author contributions

SM, CA, and TP performed literature searches, and co-wrote the review. These three authors contributed equally. KS conceived the mini review topic, performed literature searches, and co-wrote the review.

Funding

Research in the laboratory of KS is currently funded by the University of Cyprus.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Afrazi A., Branca M. F., Sodhi C. P., Good M., Yamaguchi Y., Egan C. E., et al. (2014). Toll-like receptor 4-mediated endoplasmic reticulum stress in intestinal crypts induces necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 9584–9599. 10.1074/jbc.M113.526517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apidianakis Y., Ferrandon D. (2014). Modeling hologenome imbalances in inflammation and cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 4:134. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apidianakis Y., Rahme L. G. (2011). Drosophila melanogaster as a model for human intestinal infection and pathology. Dis. Model. Mech. 4, 21–30. 10.1242/dmm.003970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge M. T., King K. Y., Boles N. C., Weksberg D. C., Goodell M. A. (2010). Quiescent haematopoietic stem cells are activated by IFN-[ggr] in response to chronic infection. Nature 465, 793–797. 10.1038/nature09135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F., Charles K. A., Mantovani A. (2005). Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7, 211–217. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezbradica J. S., Coll R. C., Schroder K. (2016). Sterile signals generate weaker and delayed macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome responses relative to microbial signals. Cell. Mol. Immunol. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/cmi.2016.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S., Stender J. D., Joshi S., Wu G., Katzenellenbogen B. S. (2016). OCT-4: a novel estrogen receptor-α collaborator that promotes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1038/onc.2016.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet M. R., McNagny K. M. (2009). Stem cells, inflammation and allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 5:13. 10.1186/1710-1492-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boiko J. R., Borghesi L. (2012). Hematopoiesis sculpted by pathogens: toll-like receptors and inflammatory mediators directly activate stem cells. Cytokine 57, 1–8. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T. S., Chen C. L., Wu Y. C., Liu J. J., Kuo Y. C., Lee K. F., et al. (2016). Inflammation promotes expression of stemness-related properties in HBV-Related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 11:e0149897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0149897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T. S., Wu Y. C., Chi C. C., Su W. C., Chang P. J., Lee K. F., et al. (2015). Activation of IL6/IGFIR confers poor prognosis of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma through induction of OCT4/NANOG expression. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 201–210. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotsarelis G., Sun T. T., Lavker R. M. (1990). Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell 61, 1329–1337. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M., Werb Z. (2002). Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420, 860–867. 10.1038/nature01322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollé L., Best J., Mei J., Al Battah F., Reynaert H., van Grunsven L. A., et al. (2010). The quest for liver progenitor cells: a practical point of view. J. Hepatol. 52, 117–129. 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Español-Suñer R., Carpentier R., Van Hul N., Legry V., Achouri Y., Cordi S., et al. (2012). Liver progenitor cells yield functional hepatocytes in response to chronic liver injury in mice. Gastroenterology 143, 1564–1575 e7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D., Kong X., Weng H., Park O., Wang H., Dooley S., et al. (2012). Interleukin-22 promotes proliferation of liver stem/progenitor cells in mice and patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology 143, 188–98.e7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa J., Mizoguchi I., Chiba Y., Hisada M., Kobayashi F., Yoshida H., et al. (2016). Promotion of expansion and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells by interleukin-27 into myeloid progenitors to control infection in emergency myelopoiesis. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005507. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin S. E., Boneca I. G., Viala J., Chamaillard M., Labigne A., Thomas G., et al. (2003). Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8869–8872. 10.1074/jbc.C200651200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T., Sulaiman O., Boyd J. G. (2003). Experimental strategies to promote functional recovery after peripheral nerve injuries. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 8, 236–250. 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2003.03029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. (2010). Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140, 883–899. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtner G. C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M. T. (2008). Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 453, 314–321. 10.1038/nature07039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins C. A., Collignon P., Adams D. N., Bowden F. J., Cook M. C. (2006). Profound lymphopenia and bacteraemia. Intern. Med. J. 36, 385–388. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01076.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Zhang C., Wang L., Zhang P., Ma D., Lv J., et al. (2015). Inflammatory signaling regulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell emergence in vertebrates. Blood 125, 1098–1106. 10.1182/blood-2014-09-601542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton J., Stoicov C., Nomura S., Rogers A. B., Carlson J., Li H., et al. (2004). Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science 306, 1568–1571. 10.1126/science.1099513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Patel P. H., Kohlmaier A., Grenley M. O., McEwen D. G., Edgar B. A. (2009). Cytokine/Jak/Stat signaling mediates regeneration and homeostasis in the Drosophila midgut. Cell 137, 1343–1355. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinushi M. (2014). Role of cancer stem cell-associated inflammation in creating pro-inflammatory tumorigenic microenvironments. Oncoimmunology 3:e28862. 10.4161/onci.28862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinushi M., Chiba S., Yoshiyama H., Masutomi K., Kinoshita I., Dosaka-Akita H., et al. (2011). Tumor-associated macrophages regulate tumorigenicity and anticancer drug responses of cancer stem/initiating cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12425–12430. 10.1073/pnas.1106645108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karakasiliotis I., Mavromara P. (2015). Hepatocellular carcinoma: from hepatocyte to liver cancer stem cell. Front. Physiol. 6:154. 10.3389/fphys.2015.00154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M. (2006). Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature 441, 431–436. 10.1038/nature04870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Clevers H. (2016). Reparative inflammation takes charge of tissue regeneration. Nature 529, 307–315. 10.1038/nature17039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizil C., Kyritsis N., Brand M. (2015). Effects of inflammation on stem cells: together they strive? EMBO Rep. 16, 416–426. 10.15252/embr.201439702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh T. J., DiPietro L. A. (2011). Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 13, e23. 10.1017/S1462399411001943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Arber N. (2009). Inflammation and colorectal cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 9, 405–410. 10.1016/j.coph.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn K. A., Manieri N. A., Liu T. C., Stappenbeck T. S. (2014). IL-6 stimulates intestinal epithelial proliferation and repair after injury. PLoS ONE 9:e114195. 10.1371/journal.pone.0114195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo K.-K., Lee K.-T., Chen K.-K., Yang Y.-H., Lin Y.-C., Tsai M.-H., et al. (2016). Positive feedback loop of OCT4 and c-JUN expedites cancer stemness in liver cancer. Stem Cells. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1002/stem.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurbet A. S., Hegde S., Bhattacharjee O., Marepally S., Vemula P. K., Raghavan S. (2016). Sterile Inflammation Enhances ECM Degradation in Integrin beta1 KO Embryonic Skin. Cell Rep. 16, 3334–3347. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyritsis N., Kizil C., Zocher S., Kroehne V., Kaslin J., Freudenreich D., et al. (2012). Acute inflammation initiates the regenerative response in the adult Zebrafish Brain. Science 338, 1353–1356. 10.1126/science.1228773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K., Davies L. C. (2015). Mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune response. Immunol. Lett. 168, 140–146. 10.1016/j.imlet.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Sayed N., Hunter A., Au K. F., Wong W. H., Mocarski E. S., et al. (2012). Activation of innate immunity is required for efficient nuclear reprogramming. Cell 151, 547–558. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Esain V., Teng L., Xu J., Kwan W., Frost I. M., et al. (2014). Inflammatory signaling regulates embryonic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell production. Genes Dev. 28, 2597–2612. 10.1101/gad.253302.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindemans C. A., Calafiore M., Mertelsmann A. M., O'Connor M. H., Dudakov J. A., Jenq R. R., et al. (2015). Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature 528, 560–564. 10.1038/nature16460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Singh S. R., Hou S. X. (2010). JAK-STAT is restrained by Notch to control cell proliferation of the Drosophila intestinal stem cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 992–999. 10.1002/jcb.22482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma N., Thanan R., Kobayashi H., Hammam O., Wishahi M., El Leithy T., et al. (2011). Nitrative DNA damage and Oct3/4 expression in urinary bladder cancer with Schistosoma haematobium infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 414, 344–349. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T., McGlinchey A., Cholewa-Waclaw J., Qu J., Tomlinson S. R., Rambukkana A. (2014). Innate immune response precedes Mycobacterium leprae-induced reprogramming of adult Schwann cells. Cell. Reprogram. 16, 9–17. 10.1089/cell.2013.0064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masaki T., Qu J., Cholewa-Waclaw J., Burr K., Raaum R., Rambukkana A. (2013). Reprogramming adult Schwann cells to stem cell-like cells by leprosy bacilli promotes dissemination of infection. Cell 152, 51–67. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer M., Matsuoka I., Wetmore C., Olson L., Thoenen H. (1992). Enhanced synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the lesioned peripheral nerve: different mechanisms are responsible for the regulation of BDNF and NGF mRNA. J. Cell Biol. 119, 45–54. 10.1083/jcb.119.1.45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalopoulos G. K. (2007). Liver regeneration. J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 286–300. 10.1002/jcp.21172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysorekar I. U., Isaacson-Schmid M., Walker J. N., Mills J. C., Hultgren S. J. (2009). Bone morphogenetic protein 4 signaling regulates epithelial renewal in the urinary tract in response to uropathogenic infection. Cell Host Microbe 5, 463–475. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai Y., Garrett K. P., Ohta S., Bahrun U., Kouro T., Akira S., et al. (2006). Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity 24, 801–812. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaoka T., Kaburagi Y., Hamaguchi Y., Hasegawa M., Takehara K., Steeber D. A., et al. (2000). Delayed wound healing in the absence of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 or L-selectin expression. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 237–247. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64534-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G., Rossi R., Commere P.-H., Jay P., Sansonetti P. J. (2014). The Cytosolic Bacterial Peptidoglycan Sensor Nod2 Affords Stem Cell Protection and Links Microbes to Gut Epithelial Regeneration. Cell Host Microbe 15, 792–798. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panayidou S., Apidianakis Y. (2013). Regenerative inflammation: lessons from Drosophila intestinal epithelium in health and disease. Pathogens 2, 209–231. 10.3390/pathogens2020209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie T. A., Strand N. S., Yang C. T., Rabinowitz J. S., Moon R. T. (2014). Macrophages modulate adult zebrafish tail fin regeneration. Development 141, 2581–2591. 10.1242/dev.098459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsouli C., Apidianakis Y., Perrimon N. (2009). Homeostasis in infected epithelia: stem cells take the lead. Cell Host Microbe 6, 301–307. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punturieri A., Szabo E., Croxton T. L., Shapiro S. D., Dubinett S. M. (2009). Lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: needs and opportunities for integrated research. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 101, 554–559. 10.1093/jnci/djp023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quante M., Bhagat G., Abrams J. A., Marache F., Good P., Lee M. D., et al. (2012). Bile acid and inflammation activate gastric cardia stem cells in a mouse model of Barrett-like metaplasia. Cancer Cell 21, 36–51. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennert R. C., Sorkin M., Garg R. K., Gurtner G. C. (2012). Stem cell recruitment after injury: lessons for regenerative medicine. Regen. Med. 7, 833–850. 10.2217/rme.12.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehl T., Cohn S., Tessner T., Schloemann S., Stenson W. F. (2000). Lipopolysaccharide is radioprotective in the mouse intestine through a prostaglandin-mediated mechanism. Gastroenterology 118, 1106–1116. 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70363-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittié L. (2016). Cellular mechanisms of skin repair in humans and other mammals. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 10, 103–120. 10.1007/s12079-016-0330-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryser S., Schuppli M., Gauthier B., Hernandez D. R., Roye O., Hohl D., et al. (2014). UVB-induced skin inflammation and cutaneous tissue injury is dependent on the MHC class I-like protein, CD1d. J. Invest. Dermatol. 134, 192–202. 10.1038/jid.2013.300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santaolalla R., Sussman D. A., Ruiz J. R., Davies J. M., Pastorini C., España C. L., et al. (2013). TLR4 activates the β-catenin pathway to cause intestinal neoplasia. PLoS ONE 8:e63298. 10.1371/journal.pone.006329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Yao Y., Weliver A., Broxmeyer H. E., Hong S. C., Chang C. H. (2008). Vaccinia virus infection modulates the hematopoietic cell compartments in the bone marrow. Stem Cells 26, 1009–1016. 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G., Lehrer M. S., Jensen P. J., Sun T. T., Lavker R. M. (2000). Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell 102, 451–461. 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00050-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthaya Kumar D. B., Chen C. L., Liu J. C., Feldman D. E., Sher L. S., French S., et al. (2016). TLR4 signaling via NANOG cooperates with STAT3 to activate Twist1 and promote formation of tumor-initiating stem-like cells in livers of mice. Gastroenterology 150, 707–719. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viebahn C. S., Yeoh G. C. (2008). What fires prometheus? The link between inflammation and regeneration following chronic liver injury. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 855–873. 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldner M. J., Neurath M. F. (2009). Colitis-associated cancer: the role of T cells in tumor development. Semin. Immunopathol. 31, 249–256. 10.1007/s00281-009-0161-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Zhao L., Fish M., Logan C. Y., Nusse R. (2015). Self-renewing diploid Axin2(+) cells fuel homeostatic renewal of the liver. Nature 524, 180–185. 10.1038/nature14863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. P., Schunck M., Kallen K. J., Neumann C., Trautwein C., Rose-John S., et al. (2004). The interleukin-6 cytokine system regulates epidermal permeability barrier homeostasis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 123, 124–131. 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22736.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphalen C. B., Takemoto Y., Tanaka T., Macchini M., Jiang Z., Renz B. W., et al. (2016). Dclk1 defines quiescent pancreatic progenitors that promote injury-induced regeneration and tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 18, 441–455. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D., Mikenberg I., Elvers M., Kaltschmidt C., Kaltschmidt B. (2006). Tumor necrosis factor α triggers proliferation of adult neural stem cells via IKK/NF-κB signaling. BMC Neurosci. 7:64. 10.1186/1471-2202-7-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson G. K., Brimacombe C. L., Rowe I. A., Reynolds G. M., Fletcher N. F., Stamataki Z., et al. (2012). A dual role for hypoxia inducible factor-1α in the hepatitis C virus lifecycle and hepatoma migration. J. Hepatol. 56, 803–809. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S. A., Steiner B., Wengner A., Lipp M., Kammertoens T., Kempermann G. (2009). Adaptive peripheral immune response increases proliferation of neural precursor cells in the adult hippocampus. FASEB J. 23, 3121–3128. 10.1096/fj.08-113944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H., Adane B., Khan N., Sullivan T., Minhajuddin M., Gasparetto M., et al. (2016). Leukemic stem cells evade chemotherapy by metabolic adaptation to an adipose tissue niche. Cell Stem Cell 19, 23–37. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yimlamai D., Christodoulou C., Galli G. G., Yanger K., Pepe-Mooney B., Gurung B., et al. (2014). Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell 157, 1324–1338. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]