Abstract

The present experiment was designed to assess the effects of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on the physiology of Brassica juncea L. seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity. Application of EBR increased the length of seedlings, dry weight, and pigment contents, polyphenols, total phenols, and organic acids under IMI toxicity. The expression of genes coding key enzymes of pigment, phenols, polyphenols, and organic acid biosynthetic pathways was also studied including CHLASE (chlorophyllase), PSY (phytoene synthase), CHS (chalcone synthase) and PAL (phenylalanine ammonialyase), CS (citrate synthase), SUCLG1 (succinyl Co-A ligase,), SDH (succinate dehydrogenase), FH (fumarate hydratase), MS (malate synthase). Multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis revealed that IMI application regressed negatively on seedling length, dry weight and total chlorophyll content. However, EBR seed treatment regressed positively on all the parameters studied. Moreover, interaction between IMI and EBR showed positive regression for growth parameters, content of pigments, total polyphenol, total phenol and malate, and expression of PSY and PAL. Negative interactions were noticed for the contents of fumarate, succinate and citrate, and expression of CHS and all genes studied related to organic acid metabolism. In conclusion, EBR enhanced the growth and contents of all studied metabolites by regulating the gene expression of B. juncea seedlings under IMI stress.

Keywords: mustard, brassinosteroids, pigments, total phenols, phenylalanine ammonialyase, GC-MS, HPLC

Introduction

Brassica juncea L. is an important oil yielding as well as vegetable crop. Various insect pests including termites, aphids, leafhoppers, and other sucking insects infest it. Pesticides are widely utilized to control insect pests, and imidacloprid (IMI) being the most preferred pesticide to control these soil and sap-sucking insects (El-Naggar and Zidan, 2013; Ko et al., 2014). To protect pesticidal air pollution and protect plants from soil insects, IMI is applied to soil before seed sowing (Bonmatin et al., 2005). However, pesticide application also causes phytotoxicity to plants resulting in their impaired growth and chlorophyll degradation (Sharma et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2016). Moreover, in plants under pesticide stress, secondary metabolites like phenolic compounds (Sharma et al., 2016a), carotenoids, anthocyanins, xanthophylls (Tan et al., 2012; Kilic et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2016b), and organic acids (Ding et al., 2014) were reported to enhance.

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are plant steroids, which are well-known to increase resistance in plants against various abiotic stresses like heavy metals and pesticides (Hayat et al., 2010; Sharma et al., 2012, 2013, 2015). 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) has similar biological functions to those of original form of brassinolide and is mostly used in physiological studies (Vardhini and Anjum, 2015). Exogenous application of EBR in crop plants has been reported to enhance their growth, pigment contents, photosynthetic efficiency, enzymatic, and non-enzymatic antioxidants (Xia et al., 2006; Sharma et al., 2012, 2013, 2015, 2016a; Vardhini and Anjum, 2015; Zhou et al., 2015). It has also been reported that exogenous application of EBR to plants decreases the pesticide residues (Xia et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2016c,d). Phenolic compounds and pigments which act as antioxidants including anthocyanins, carotenoids, and xanthophylls also got enhanced after the exogenous application of EBR in different plants (Chen et al., 2011; Nakabayashi et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2016a,d). Moreover, EBR application may also modulates gene expression in plants to enhance their resistance against pesticide stress (Xia et al., 2009; Sharma et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015). Treatment of EBR via seed soaking before sowing has been reported to ameliorate the pesticide toxicity in plants (Sharma et al., 2012, 2016a). Keeping in mind the protective roles of EBRs in plants under pesticide toxicity, the present study was undertaken to assess the effects of EBR seed soaking before sowing on B. juncea seedlings grown under IMI stress.

Materials and methods

Raising of plant material

Seeds of B. juncea (cv. RLC-1) were given pre-sowing treatment with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) solutions (0 and 100 nM EBR/L) for 8 h. Petri-plates were lined with Whatman1 filter paper and were supplemented with different imidacloprid (IMI) concentrations (0, 150, 200, and 250 mg IMI/L). The EBR treated seeds were rinsed with distilled water and grown in Petri-plates supplemented with IMI solutions (three petri-plates for each treatment). The Petri-plates were kept in seed germinator (temperature = 25 ± 0.5°C, photoperiod = 16 h, light intensity = 175 μmol m−2 s−1) and the seedlings were harvested 10 days after sowing for further analysis.

Estimation of growth parameters

Length of seedling was measured by scale and for dry weight, the seedlings were weighed after drying them at 70°C for 48 h.

Estimation of pigment content (chlorophyll, carotenoid, anthocyanin, and xanthophyll content)

Chlorophyll contents were estimated according to the method given by Arnon (1949), whereas carotenoid content was estimated as described by Kapoor et al. (2014). One gram of fresh seedlings were crushed in 4 ml of 80% acetone. The extract was then centrifuged (4°C) at 12,000 × rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was used to determine the contents of chlorophylls and carotenoids. Absorbance was taken using spectrophotometer at 645 and 663 nm for chlorophylls, whereas 480 and 510 nm for carotenoids.

Method given by Mancinelli (1984) was followed to determine the anthocyanin content. One gram of fresh seedlings were crushed in 3 ml of extraction solvent containing 0.03 ml of hydrochloric acid (HCl), 0.6 ml of distilled water, and 2.37 ml of methanol. The crushed sample was then centrifuged (4°C) at 12,000 × rpm for 20 min. and the absorbance was recorded spectrophotometerically at 530 and 657 nm.

Association of Official Agricultural Chemists (AOAC) procedure given by Lawrence (1990) was followed to determine the xanthophyll content. Fifteen milliliter of solvent mixture (5 ml hexane, 3.5 ml acetone, 3 ml ethanol, 3.5 ml toluene) was added to 50 ml flask containing 25 mg dried seedling powder. The flask was shaken for 10–15 min. After shaking, 1 ml of 40% methanolic potassium hydroxide (KOH) was poured into the flask and was incubated at 56°C for 20 min (water bath) followed by another incubation in dark for 1 h. After incubation, 15 ml of hexane was added to the flask and then shaken well for 1 min. The 50 ml volume of flask was made up by adding 10% sodium sulfate solution followed by incubation in dark for 1 h. The upper phase was collected in 25 ml volumetric flask and the makeup of the volume was done using hexane. Absorbance was taken using spectrophotometer at 474 nm.

Determination of total phenols

Method given by Singleton and Rossi (1965) was followed to determine the total phenol content. One gram of fresh seedlings were homogenized in 5 ml of 60% ethanol followed by incubation at 60°C for 30 min. One hundred and twenty five microliter sample from incubated mixture was added to 0.625 ml of Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) reagent and 0.5 ml of 7.5% Na2CO3 (sodium carbonate) followed by incubation for 2 h at 25°C. Absorbance was taken at 765 nm by spectrophotometer.

Quantification of polyphenols using ultra high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC)

Method described by Sharma et al. (2016a) was followed to determine the polyphenol content. One gram of fresh seedlings were crushed in 5 ml of 80% methanol followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × rpm for 15 min. Ten microliter of sample was injected into UHPLC system equipped with SPD-M20A photodiode array detector. Analytical column used was C18 (column length = 150 mm; internal diameter = 4.6 mm; pore size = 100 Å; company = Spincotech) and wavelength selected for absorbance was 280 nm. Acetic acid (0.01%) and methanol (HPLC grade, 100%) were used as mobile phase A and B, respectively. Flow rate was set at 1 ml/min. Gradient information: 0–1 min, 30% B; 12 min, 45% B; 15 min, 75% B; 16.6 min, 50%; 20 min, 25%; 21 min, 30%. Program was terminated at 22 min (elution time-4 min). The polyphenols were identified and quantified using standards which were analyzed before running plant samples (Shimadzu LabSolutions software).

Quantification of organic acids using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

Sample preparation

Method given by Chen et al. (2001) was modified to estimate organic acids using GC-MS. Extraction of organic acids was done by adding 0.5 ml of 0.5 N HCl and 0.5 ml of methanol to 50 mg of dried seedling powder followed by shaking for 3 h and then centrifuged at 12,000 × rpm for 10 min. To the supernatant, 300 μl of methanol and 100 μl of 50% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) were added followed by overnight incubation in water bath at 60°C. The mixture was cooled down to 25°C and 800 μl of chloroform and 400 μl of distilled water were added to it followed by vortexing for 1 min. The lower chloroform layer was used to estimate organic acids using GC-MS.

Analysis using GC-MS

To estimate organic acid content, 2 μl of sample (lower chloroform layer) was injected into GC-MS system. GC conditions: Carrier gas used was helium, initial column temperature was 50°C (hold for 1 min) which was increased at 25°C/min to 125°C followed by further increase at 10°C/min to 300°C and held for 15 min. Injection temperature was 250°C, mode of injection was split, flow of gas in column was 1.7 ml/min, and analytical column used was DB-5ms. MS conditions: Ion source temperature was set at 200°C and interface temperature was 280°C, solvent cut time was 3 min, detector gain mode: relative. Organic acids viz. citrate, fumarate, malate, and succinate were detected by comparing their mass spectra using National Institute of Standard and Technology (NIST08s) and Wiley 7 library. The quantification of these organic acids was done using standard curve.

Gene expression through quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Trizol method (Invitrogen) was followed to extract total RNA from 100 mg of B. juncea seedlings. RNA to cDNA kit (Invitrogen) was used to make cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA. No DNase was used in the experiment and to make sure that there was no genomic DNA contamination, a PCR reaction was set using total RNA extracted as template and no amplified product was detected. EMBL and Genbank were used to design gene specific primers (Table 1) and actin was taken as an internal control. qRT-PCR was done in three biological replicates using Power SYBR green PCR master mix and StepOne qRT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C (15 s), annealing temperature (30 s), and extension at 72°C (1 min). Method given by Livak and Schmittgen (2001) was referred to calculate fold change in gene expression from threshold values (Ct) obtained from qRT-PCR analysis (StepOne Software version 2.3, Applied Biosystems).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for gene expression analysis using qRT-PCR.

| Gene name | Primer sequence | Annealing temp. (°C) | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | Forward primer 5′ CTTGCACCTAGCAGCATGAA 3′ | 52 | 154 |

| Reverse primer 5′ GGACAATGGATGGACCTGAC 3′ | |||

| CS | Forward primer 5′ TGGGACAGAGCTCTTGGACT 3′ | 51 | 140 |

| Reverse primer 5′ TCAGTGTGGAAGGAACACCA 3′ | |||

| SUCLG1 | Forward primer 5′ ATTATGCCGGGTTACATCCA 3′ | 49 | 141 |

| Reverse primer 5′ AAAAGGATCCCCACCAATTC 3′ | |||

| SDH | Forward primer 5′ GTGGTCAGGCCTATCGTTGT 3′ | 54 | 154 |

| Reverse primer 5′ CCCTGGCAAGTACCATCACT 3′ | |||

| FH | Forward primer 5′ CTCTCCACCATCTCGTCTCC 3′ | 49 | 141 |

| Reverse primer 5′ CCCTGAACGAGGTCGAATAA 3′ | |||

| MS | Forward primer 5′ GGGCATGTGAGGTACGCTAT 3′ | 52 | 123 |

| Reverse primer 5′ AGAGGCACAAACCCATTCAC 3′ | |||

| CHLASE | Forward primer 5′ GAATATCCGGTGGTGATGCT 3′ | 49 | 161 |

| Reverse primer 5′ TCCGCCGTTGATTTTATCTC 3′ | |||

| PSY | Forward primer 5′ TGGGTTGGTAAGGGCTGTAG 3′ | 51 | 155 |

| Reverse primer 5′ CGCTCGAAGACACAACACTC 3′ | |||

| CHS | Forward primer 5′ CAAGGCGGAGAAGATGAGAG 3′ | 54 | 113 |

| Reverse primer 5′ CATCTTCCGCAGACTTCCTC 3′ | |||

| PAL | Forward primer 5′ AAACTCCGTCAACGACAACC 3′ | 54 | 142 |

| Reverse primer 5′ AGCGAACATGAGCTTCCCTA 3′ |

CS, citrate synthase; SUCLG1, succinyl Co-A ligase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; FH, fumarate hydratase; MS, malate synthase; CHLASE, chlorophyllase; PSY, phytoene synthase; CHS, chalcone synthase; and PAL, phenylalanine ammonialyase.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was done using two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD, multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis (self-coded softwares in MS-excel 2010), and artificial neural networks (ANN) using Statistica-12 (Kumar et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2016a,d).

Results

Effect of EBR seed soaking on growth parameters

As compared to control, seeding length and biomass (dry weight) was reduced by 420.78% and 220.68%, respectively under IMI toxicity (250 mg/L) over the control. However, seed soaking with EBR significantly enhanced the length of B. juncea seedlings by 179.21% and biomass by 137.93% grown under IMI stress (Table 2). Data analysis using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD showed significant differences for seedling length (FIMI, FEBR, and FIMI × EBR = p < 0.001) as well as dry weight (FIMI, FEBR, and FIMI × EBR = p < 0.001) in B. juncea seedlings. Multiple linear regression (MLR) analysis of data also revealed the enhanced growth of seedlings raised from EBR soaked seeds grown under IMI stress. Negative β-regression coefficients for IMI showed decrease in seedling length and biomass as a consequence of IMI toxicity. Positive β-regression coefficients for EBR and interaction IMI × EBR showed recovery of the seedling growth, which was negatively affected by IMI toxicity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on growth parameters in Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity.

| Treatments | Seedling length (cm/seedling) | Dry weight (mg/seedling) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMI (mg/L) | 24-EBR (nM) | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 14.53ab ± 0.62 | 18.6ab ± 2.17 | |||

| 0 | 100 | 15.09a ± 1.59 | 19.9a ± 1.66 | |||

| 150 | 0 | 10.87c ± 1.14 | 16.1abc ± 1.18 | |||

| 150 | 100 | 13.71ab ± 0.73 | 19.6a ± 0.97 | |||

| 200 | 0 | 6.76d ± 0.80 | 9.2d ± 0.91 | |||

| 200 | 100 | 12.10bc ± 0.60 | 15.4bc ± 1.57 | |||

| 250 | 0 | 2.79e ± 0.22 | 5.8d ± 0.92 | |||

| 250 | 100 | 7.79d ± 0.54 | 13.5c ± 1.35 | |||

| TWO-WAY ANOVA | ||||||

| F-ratios & HSD | FIMI = 439*** | FIMI = 208*** | ||||

| FEBR = 310*** | FEBR = 220*** | |||||

| FIMI × EBR = 32.2*** | FIMI × EBR = 20.3*** | |||||

| HSD = 2.46* | HSD = 3.98* | |||||

| Multiple linear regression equation | β regression coefficients | MLR | ANN | |||

| βIMI | βEBR | βIMI × EBR | r | r (validation) | ||

| Seedling length (cm) = 15.38−0.03 X1 + 0.0042 X2 + 0.0001 X1X2 | −0.9825 | 0.0522 | 0.4873 | 0.8984** | 0.9549*** | |

| Dry weight (mg/seedling) = 19.77−0.033 X1 + 0.0088 X2 + 0.0002 X1X2 | −0.9279 | 0.0929 | 0.5245 | 0.8801** | 0.9666*** | |

Treatments with same superscripts indicates no significant difference at p < 0.05,

indicate significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 respectively. X1, IMI; X2, EBR; r, correlation coefficient. Data are mean±standard deviation of 10 seedlings, two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD, multiple linear regression analysis and and artificial neural networks (ANN).

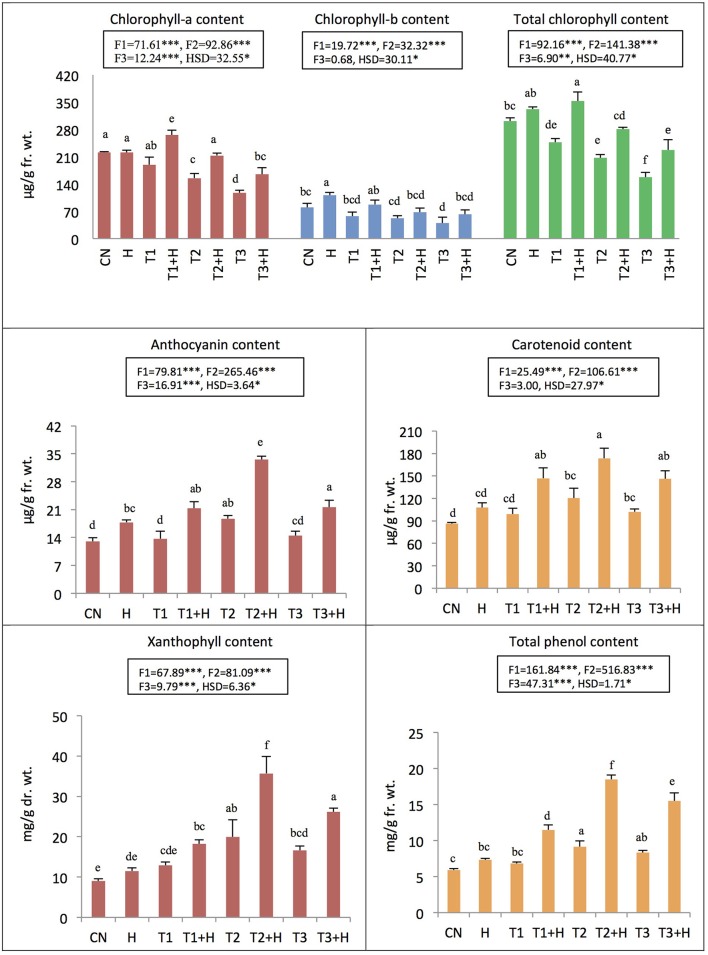

Effect of EBR seed soaking on pigment system

Total chlorophyll content was decreased by 91.12% as a result of IMI toxicity (250 mg/L). However, seed soaking with 100 nM EBR resulted in the recovery of chlorophyll content by 44.13% under IMI stress (Figure 1). Furthermore, seedlings treated with EBR, grown under 200 mg IMI/L significantly enhanced the contents of carotenoids (101.10%), anthocyanins (157.55%), and xanthophylls (296.99%) in B. juncea seedlings, as compared to control (Figure 1). Two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD revealed that contents of pigments were significantly different in B. juncea seedlings under different treatments. MLR analysis revealed increase in the contents of pigments after EBR seed soaking. Concentration of IMI was negatively regressed upon chlorophyll content, indicating the degradation of chlorophyll under IMI stress. However, IMI showed positive regression with contents of carotenoids, anthocyanins, and xanthophylls, implying an increase in these pigments under IMI stress. EBR seed application was also regressed positively on the contents of all the pigments including chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, total chlorophyll, carotenoids, anthocyanins, and xanthophylls. Moreover, it was observed that interactions between IMI and EBR were positive for all pigments studied except chlorophyll-b, where interaction (IMI × EBR) was noticed to be negative (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on pigment and phenol contents in Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity. Data are mean ± standard deviation, two-way ANOVA, and Tukey's HSD (three biological replicates). Treatments with same letter indicates no significant difference at p < 0.05. F1, F2, and F3 are F-ratios for IMI, EBR, and IMI × EBR, respectively. CN, control; H, 100 nM EBR; T1, 150 mg IMI/L DW; T2, 200 mg IMI/L DW; and T3, 250 mg IMI/L DW. ** and *** indicate significant at p < 0.01 and p < 0.001, respectively.

Effect of EBR on phenolic compounds

In the seedlings of B. juncea, nine polyphenols were detected (Table 3). It was observed that, as compared to control seedlings, the total polyphenols were increased by 101.22% in seedlings raised from 100 nM EBR treated seeds grown under IMI pesticide (200 mg/L) stress (Table 3). The total phenol content also enhanced by 213.56% with 100 nM RBR treated B. juncea under 200 mg/L IMI stress (Figure 1). Analysis of total polyphenol and total phenol contents using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD also showed significant difference (FIMI, FEBR, and FIMI × EBR = p < 0.001). MLR analysis also revealed that both IMI and EBR enhanced the content of total phenols. Concentrations of IMI as well as EBR were regressed positively on the content of total phenols. Additionally, positive interaction was observed between IMI and EBR for total phenol content (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on polyphenol contents in Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity.

| TREATMENT | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBR (nM) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 |

| IMI (mg/L) | 0 | 0 | 150 | 150 | 200 | 200 | 250 | 250 |

| POLYPHENOL CONTENT (μg/g fr. wt.) | ||||||||

| Gallic acid | – | – | – | 3.62 ± 0.17 | – | – | – | – |

| Catechin | 16.86 ± 3.39 | 62.15 ± 4.88 | 6.76 ± 1.09 | 25.31 ± 4.27 | 59.20 ± 7.59 | 206.17 ± 16.25 | 14.05 ± 2.43 | 16.93 ± 0.63 |

| Chlorogenic acid | – | 18.22 ± 2.32 | 8.74 ± 0.97 | 25.31 ± 5.37 | 16.10 ± 4.32 | 58.85 ± 7.53 | 4.81 ± 0.76 | 4.36 ± 0.65 |

| Caffeic acid | 50.05 ± 5.99 | 29.43 ± 4.14 | 49.30 ± 2.77 | 49.22 ± 8.71 | 30.35 ± 4.57 | 0.77 ± 0.12 | 104.71 ± 8.40 | 61.58 ± 5.32 |

| Rutin | 11.39 ± 2.12 | – | 24.28 ± 4.54 | 13.62 ± 3.43 | – | 13.11 ± 1.07 | 24.46 ± 4.78 | 31.76 ± 6.15 |

| Ellagic acid | 1.70 ± 0.18 | – | 5.98 ± 0.68 | 2.35 ± 0.11 | – | – | 2.50 ± 0.25 | 1.18 ± 0.03 |

| tert-Butyl hydroquinone | 0.15 ± 0.02 | – | 3.27 ± 0.39 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 1.80 ± 0.04 | 3.05 ± 0.21 | 1.67 ± 0.22 | 0.31 ± 0.08 |

| Quercetin | 1.77 ± 0.14 | 0.02 ± 0.004 | 1.33 ± 0.11 | 1.16 ± 0.24 | 10.54 ± 1.23 | – | 2.86 ± 0.28 | 23.87 ± 3.31 |

| Kaempferol | 97.80 ± 10.22 | 89.20 ± 16.63 | 100.34 ± 11.53 | 98.18 ± 12.76 | 164.86 ± 31.81 | 80.03 ± 17.69 | 88.27 ± 18.58 | 216.33 ± 28.73 |

| Total | 179.7c ± 21.19 | 199.0c ± 19.62 | 199.9c ±7.95 | 238.3b ± 28.62 | 282.8d ± 23.99 | 361.9a ± 14.14 | 243.3b ± 18.96 | 356.3a ± 37.86 |

| F-ratios and HSD for total polyphenol content, FIMI = 456.66***, FEBR = 34.556***, FIMI × EBR = 34.555***, HSD = 23.33* | ||||||||

| Multiple linear regression equation | β regression coefficients | MLR | ANN | |||||

| βIMI | βEBR | βIMI × EBR | r | r (validation) | ||||

| Polyphenol content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 177.1 + 0.329 X1 + 0.0947 X2 + 0.0035 X1X2 | 0.4494 | 0.0691 | 0.5156 | 0.8619*** | 0.8738*** | |||

Statistical analysis was done only for total polyphenol content. For individual polyphenol, statistical analysis was not done due to non-uniformity in their detection using HPLC. (−) means not detected. Treatments with same superscripts indicates no significant difference at p < 0.05. r, correlation coefficient.

indicate significant at p < 0.05, and p < 0.001, X1, IMI; X2, EBR. Data are mean ± standard deviation (three biological replicates), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD, multiple linear regression analysis (MLR) and artificial neural networks (ANN).

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression (MLR) and artificial neural network (ANN) analysis showing effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on pigments and total phenol contents, and gene expression in Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity.

| Multiple linear regression equation | β regression coefficients | MLR | ANN | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| βIMI | βEBR | βIMI × EBR | r | r (validation) | |

| Chlorophyll-a content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 229.02 − 0.258 X1 + 0.0707 X2 + 0.0017 X1X2 | −0.7791 | 0.0792 | 0.5611 | 0.7724*** | 0.9960*** |

| Chlorophyll-b content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 81.29 − 0.106 X1 + 0.3187 X2 − 3 × 10−4 X1X2 | −0.6259 | 0.7006 | −0.2062 | 0.9068*** | 0.9837*** |

| Total chlorophyll content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 310.24 − 0.364 X1 + 0.3892 X2 + 0.0014 X1X2 | −0.7807 | 0.3102 | 0.3241 | 0.8562*** | 0.9937*** |

| Carotenoid content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 86.90 + 0.0669 X1 + 0.2345 X2 + 0.0008 X1X2 | 0.3092 | 0.4026 | 0.4101 | 0.8910*** | 0.9158*** |

| Anthocyanin content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 13.05 + 0.0086 X1 + 0.0512 X2 + 0.0002 X1X2 | 0.1841 | 0.4064 | 0.3601 | 0.7829*** | 0.9728*** |

| Xanthophyll content (mg/g dr. wt.) = 8.80 + 0.0258 X1 + 0.0224 X2 + 0.0003 X1X2 | 0.4168 | 0.1339 | 0.4737 | 0.8327*** | 0.9134*** |

| Total phenol content (μg/g fr. wt.) = 5.79 + 0.0078 X1 + 0.013 X2 + 0.0002 X1X2 | 0.2485 | 0.1536 | 0.6729 | 0.9213*** | 0.9066*** |

| CS (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0068 X1 + 0.0277 X2 - 1 × 10−4 X1X2 | 0.6281 | 1.2822 | −1.007 | 0.9117*** | 0.8090*** |

| SUCLG1 (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0029 X1 + 0.0.0372 X2 − 6 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.1781 | 1.1436 | −0.2962 | 0.9875*** | 0.9870*** |

| SDH (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0051 X1 + 0.0199 X2 − 7 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.5806 | 1.1351 | −0.7171 | 0.8480** | 0.5441*** |

| FH (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0029 X1 + 0.0318 X2 − 5 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.2068 | 1.1372 | −0.3193 | 0.9707*** | 0.9475*** |

| MS (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0046 X1 + 0.0289 X2 − 4 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.3322 | 1.0422 | −0.2403 | 0.9342*** | 0.9489*** |

| CHLASE (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0083 X1 + 0.0026 X2 − 9 × 10−5 X1X2 | 1.1463 | 0.1788 | −1.1018 | 0.9349*** | 0.8785*** |

| PSY (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0136 X1 + 0.0028 X2 + 6 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.7504 | 0.0771 | 0.2964 | 0.9697*** | 0.9362*** |

| CHS (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0166 X1 + 0.0038 X2 − 8 × 10−6 X1X2 | 0.9839 | 0.1116 | −0.0415 | 0.9642*** | 0.9063*** |

| PAL (gene expression fold change) = 1 + 0.0049 X1 + 0.0112 X2 + 0.0002 X1X2 | 0.2065 | 0.2383 | 0.6588 | 0.9338*** | 0.9207*** |

CS, citrate synthase; SUCLG1, succinyl Co-A ligase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; FH, fumarate hydratase; MS, malate synthase; CHLASE, chlorophyllase; PSY, phytoene synthase; CHS, chalcone synthase; and PAL, phenylalanine ammonialyase.

indicate significant at p < 0.01 and p < 0.001. r, correlation coefficient; X1, IMI; X2, EBR.

Effect of EBR on organic acids

The contents of organic acids viz. fumarate, succinate, malate, and citrate were observed to enhance by 3.31, 27.05, 328.06, and 63.86% in the seedlings raised from EBR treated/untreated seeds grown under IMI pesticide stress, when compared to control seedlings (Table 5). Significant differences in the contents organic acids including fumarate (FIMI = p < 0.001, FEBR = p < 0.001, and FIMI × EBR = p < 0.05), succinate (FIMI = p < 0.001 and FEBR = p < 0.001), malate (FIMI = p < 0.001, FEBR = p < 0.001, and FIMI × EBR = p < 0.01), and citrate (FIMI = p < 0.001, FEBR = p < 0.001) were observed after analyzing the data using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD (Table 5). Positive β-regression coefficients obtained from MLR analysis of the contents of organic acids also revealed that both IMI as well as EBR resulted in increase in the contents of organic acids in B. juncea seedlings. However, βIMI × EBR revealed that there were negative interactions between IMI and EBR for the contents of fumarate, succinate, and citrate, whereas positive interaction between IMI and EBR was noticed for malate content (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on contents of organic acids in Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity.

| Treatments | Fumarate (mg/g DW) | Succinate (mg/g DW) | Malate (mg/g DW) | Citrate (mg/g DW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMI (mg/L) | 24-EBR (nM) | ||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.3709d±0.0006 | 0.85d±0.01 | 1.39c±0.06 | 3.21c±0.45 | ||

| 0 | 100 | 0.3746bcd±0.0003 | 0.96bc±0.04 | 1.47c±0.08 | 3.86bc±0.12 | ||

| 150 | 0 | 0.3727cd±0.0032 | 0.94bcd±0.05 | 2.81bc±0.31 | 3.81bc±0.31 | ||

| 150 | 100 | 0.3765bc±0.0030 | 1.00ab±0.04 | 5.94a±1.77 | 4.32b±0.31 | ||

| 200 | 0 | 0.3757bcd±0.0012 | 0.97b±0.02 | 2.82bc±0.05 | 4.37b±0.21 | ||

| 200 | 100 | 0.3832a±0.0019 | 1.08a±0.04 | 5.91a±1.03 | 5.26a±0.51 | ||

| 250 | 0 | 0.3782b±0.0008 | 0.86d±0.03 | 3.29bc±0.07 | 3.40c±0.08 | ||

| 250 | 100 | 0.3784ab±0.0002 | 0.88cd±0.02 | 4.59ab±0.46 | 3.80bc±0.29 | ||

| TWO-WAY ANOVA | |||||||

| F-ratios & HSD | FIMI = 18.3*** | FIMI = 24.7*** | FIMI = 21.1*** | FIMI = 20.8*** | |||

| FEBR = 27.3*** | FEBR = 27.8*** | FEBR = 38.3*** | FEBR = 22.5*** | ||||

| FIMI × EBR = 4.09* | FIMI × EBR = 2.16 | FIMI × EBR = 5.84** | FIMI × EBR = 0.67 | ||||

| HSD = 0.005* | HSD = 0.089* | HSD = 2.13* | HSD = 0.85* | ||||

| Multiple linear regression equation | β regression coefficients | MLR | ANN | ||||

| βIMI | βEBR | βIMI × EBR | r | r (validation) | |||

| Fumarate (mg/g dr. wt.) = 0.37 + 3 × 10−5 X1 + 5 × 10−5 X2 − 5 × 10−8 X1X2 | 0.6722 | 0.5846 | −0.1166 | 0.7947*** | 0.4726*** | ||

| Succinate (mg/g dr. wt.) = 0.87 + 0.0002 X1 + 0.0011 X2 − 2 × 10−6 X1X2 | 0.2256 | 0.6938 | −0.2975 | 0.4983* | 0.8787*** | ||

| Malate (mg/g dr. wt.) = 1.46 + 0.0075 X1 + 0.0073 X2 + 8 × 10−5 X1X2 | 0.3906 | 0.2050 | 0.4349 | 0.8234*** | 0.9633*** | ||

| Citrate (mg/g dr. wt.) = 3.36 + 0.0022 X1 + 0.0067 X2 − 4 × 10−6 X1X2 | 0.3155 | 0.5119 | −0.0589 | 0.5499** | 0.9236*** | ||

Treatments with same superscripts indicates no significant difference at p < 0.05.

indicate significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 respectively. r, correlation coefficient; X1, IMI; X2, EBR. Data are mean ± standard deviation (three biological replicates), two-way ANOVA, Tukey's HSD, multiple linear regression analysis and and artificial neural networks (ANN).

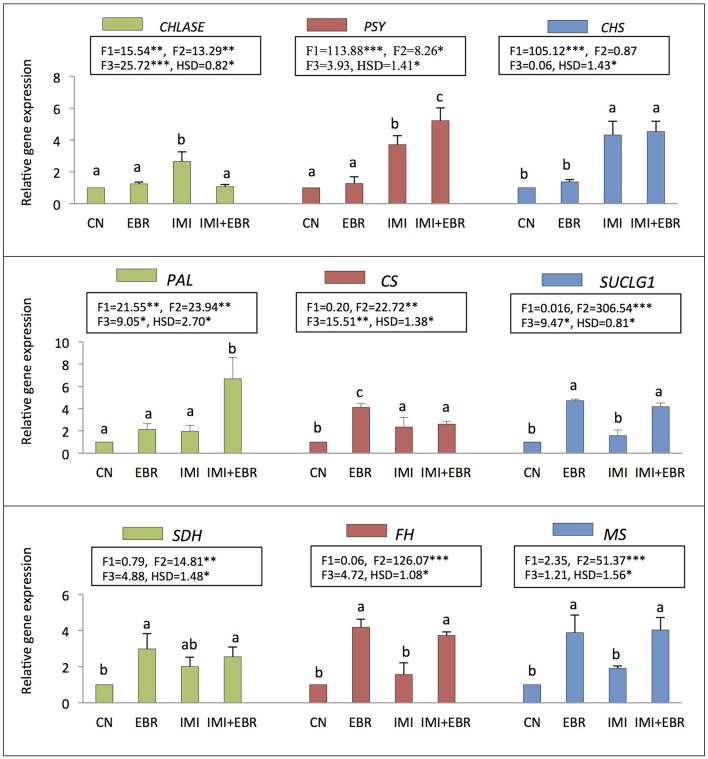

Gene expression

In the present study, as compared to control seedlings, the expression of gene CHLASE (encoding chlorophyllase) was observed to increase by 2.66-fold under IMI toxicity, but seed soaking with EBR significantly reduced the expression of CHLASE to 1.07-fold in the seedlings under IMI toxicity (Figure 2). Data analysis using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD showed significant difference for CHLASE expression in B. juncea seedlings (FIMI p < 0.01, FEBR p < 0.01, FIMI × EBR p < 0.001). MLR analysis of the fold change in CHLASE expression also revealed the increased expression of gene with IMI toxicity and EBR application (positive βIMI-value), whereas interaction between IMI and EBR was observed to be negative (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Effect of seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide (EBR) on gene expression of Brassica juncea seedlings grown under imidacloprid (IMI) toxicity. Data are mean ± standard deviation, two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD (three biological replicates). Treatments with same letter indicates no significant difference at p < 0.05. F1, F2, and F3 are F-ratios for IMI, EBR, and IMI × EBR, respectively. CN, control; EBR, 100 nM EBR; IMI, 200 mg IMI/L DW; CS, citrate synthase; SUCLG1, succinyl Co-A ligase; SDH, succinate dehydrogenase; FH, fumarate hydratase; MS, malate synthase; CHLASE, chlorophyllase; PSY, phytoene synthase; CHS, chalcone synthase; and PAL, phenylalanine ammonialyase. *, **, and *** indicate significant at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively.

Further, in comparison to control seedlings, the expression of PSY (encoding phytoene synthase) and CHS (encoding chalcone synthase) was significantly enhanced by 5.22 and 4.54-folds respectively in the seedlings raised from EBR treated as well as untreated seeds grown under IMI stress (Figure 2). Significant differences in expression PSY (FIMI p < 0.001, FEBR p < 0.05) and CHS (FIMI × EBR p < 0.001) were observed after analyzing the data using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD. MLR analysis of fold change in gene expression also revealed the role of EBR in modulation of gene expression of PSY and CHS. Concentrations of IMI as well as EBR were regressed positively on the fold change in gene expression of PSY and CHS, thus revealing enhanced expressions of these genes under both the treatments. Moreover, interaction between IMI and EBR was positive for PSY expression, whereas negative interaction was observed for the expression of CHS (Table 4).

In the present study, the expression of PAL was also observed to enhance significantly by 6.68-fold in the seedlings raised from EBR treated seeds and grown under IMI stress (Figure 2). After analyzing the data using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD, significant difference in the expression of PAL was observed (FIMI p < 0.01, FEBR p < 0.01, FIMI × EBR p < 0.05). MLR analysis of the fold change in gene expression also confirmed the role of EBR in increasing the PAL gene expression under IMI pesticide stress. Positive β-regression coefficients were observed for IMI, EBR, and IMI × EBR (Table 4).

The expression of genes encoding the key enzymes involved in organic acid metabolism was also studied to understand the role of EBR in organic acid metabolism under IMI pesticide stress. It was observed that as compared to control seedlings, the expression of CS (encoding citrate synthase, 2.35-fold), SUCLG1 (encoding succinyl-Co-A ligase, 1.57-fold), SDH (encoding succinate dehydrogenase, 2.01-fold), FH (encoding fumarate hydratase, 1.57-fold), and MS (encoding malate synthase, 1.91-fold) were increased in B. juncea seedlings raised from untreated seeds and grown under IMI pesticide toxicity (Figure 2). However, seed soaking with 100 nM EBR and germinating them under IMI toxicity resulted in further enhancement in expression of CS (2.61-fold), SUCLGD1 (4.18-fold), SDH (2.55-fold), FH (3.73-fold), and MS (4.03-fold). Data analysis using two-way ANOVA and Tukey's HSD showed significant differences in the expression of CS (FEBR p < 0.01, FIMI × EBR p < 0.01), SUCLG1 (FEBR p < 0.001, FIMI × EBR p < 0.05), SDH (FEBR p < 0.01), FH (FEBR p < 0.001), and MS (FEBR p < 0.001). MLR analysis showed that gene expression in seedlings under IMI stress as well as after the EBR seed treatment was increased as indicated by positive β-regression coefficients. Whereas, negative interactions were noticed between IMI and EBR treatments for the expression of all genes studied related to organic acid metabolism (Table 4).

Analysis of data using artificial neural networks (ANN)

From ANN analysis of data, it has been observed that correlation between experimental values and simulated values for all the parameters studied against, using EBR and IMI as inputs are highly correlated (Tables 2–4). This revealed that ANN can simulate the experimental data with high level of significance. Earlier studies have also reported high correlations for enzymatic antioxidants, and pesticide residues against applied IMI and EBR (Sharma et al., 2016c).

Discussion

In the present study, seed soaking with EBR resulted in recovery of the growth of B. juncea seedlings raised under IMI toxicity. The enhancement in seedling growth after the application of EBR might be due to the ability of BRs to modulate cellulose biosynthesis, along with cell division and cell elongation (González-García et al., 2011; Hacham et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2011). Increase in growth parameters after the exogenous application of BRs has also been reported by Sharma et al. (2015) in rice seedlings.

Decrease in chlorophyll contents might due to the degradation of chloroplast, oxidation of chlorophylls as a result of oxidative stress and enhanced activity of chlorophyllase enzyme (Kato and Shimizu, 1985; Parida et al., 2002; Harpaz-Saad et al., 2007). Moreover, it has also been reported that BRs up-regulate the transcripts and process of translation during chlorophyll biosynthesis and reduction of chlorophyll degradation (Kalinich et al., 1985; Honnerova et al., 2010). In the present study, it has been observed that EBR reduced the expression of CHLASE under IMI stress, suggesting the possible reason for recovery of chlorophyll contents in B. juncea seedlings grown under IMI stress.

Increase in carotenoid, xanthophyll, and anthocyanin contents has been observed with the application of EBR under IMI stress. Since phytoene synthase (PSY) is a key enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of carotenoids and xanthophylls, the change in the expression of PSY could be one of the reasons for alterations in the contents of carotenoids and xanthophylls. In the present study, the expression of PSY as well as the contents of carotenoids and xanthophylls were observed to enhance in seedlings raised from EBR treated seeds and grown under IMI stress. Chalcone synthase (CHS) plays an important role in the biosynthetic pathway of anthocyanins, and in the present experiment, the expression of CHS was observed to increase in B. juncea seedlings raised from EBR treated seeds grown in IMI solutions. The enhanced contents of anthocyanins in B. juncea seedlings might be due to the modulation of CHS by EBR. Additionally, Luan et al. (2013) also reported that BRs up-regulate the genes which are responsible for the biosynthesis of anthocyanins. Moreover, BRs have also been reported to induce anthocyanin biosynthesis by BRs-cytokinin mediated regulation of late anthocyanin biosynthetic genes (Yuan et al., 2015).

The contents of phenolic compounds were enhanced in the present study with the application of IMI as well as EBR. The enhanced levels of polyphenols and total phenolic contents might be due to the stress-induced activation of phenylpropanoid pathway (Korkina, 2007). Further, in the present study, application of EBR also increased the activity of phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL), a key enzyme of phenylpropanoid pathway (Ahammed et al., 2013; Xi et al., 2013). The results of present study are in agreement with the studies carried out by Siddiqui and Ahmed (2006). They reported the enhanced contents of total phenols in soybean plants under pesticide stress. BRs have also been reported to increase the total phenol contents in Vitis vivifera L. (Champa et al., 2015) and in Cichorium endivia L. (Serna et al., 2013).

In the present experiment, contents of organic acids studied were increased after the application of IMI and EBR. It is well known that citrate synthase catalyses the synthesis of citrate, succinyl-Co-A ligase catalyses the synthesis of succinate, succinate dehydrogenase catalyses the synthesis of fumarate, and fumarate hydratase and malate synthase catalyses the synthesis of malate (Lehninger et al., 2008). The EBR mediated regulation of the genes (CS, SUCLG1, SDH, FH, and MS) encoding enzymes involved in organic acid metabolism might be a possible reason of increased contents of all the organic acids under IMI toxicity. Moreover, the biosynthesis of organic acids in plants has been reported to get enhanced under abiotic stress conditions (Timpa et al., 1986; Li et al., 2000; Ma, 2000). The present study also reported increase in organic acid contents under pesticide stress, and seed soaking with EBR further enhanced their levels, proposing the role of these organic acids in ameliorating pesticide toxicity.

In the present study, BR-modulated mitigation of IMI toxicity might be due to the BR-signaling which regulated the expression of genes studied in the present work. It is well known that BR signaling starts with BRI1 (BRASSINOSTEROID SENSTIVE 1) and its co-receptor BAK1 (BRI1-associated receptor kinase 1; Hao et al., 2013). BKI1 (BRI1 KINASE INHIBTOR 1) has been reported to undergo tyrosine phosphorylation as a result of BR signaling (Jaillais et al., 2011). Moreover, CaM (calmodulin) binding to BRI1 and DWF4 (DWARF4) has also been reported in Ca2+ dependent manner which is supposed to be an important step in BR signaling (Du and Poovaiah, 2005; Oh et al., 2012). After receiving BR signal, process of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation leads to stimulation of transcription factors (TFs) which control BR-mediated gene expression, involving BES1 (BRI1-EMS-Supressor 1) and BZR (Brasssinozole resistant 1). These TFs are regulated by BIN2 (BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSTIVE 2), BSK1 (BR-SIGANALLING KINASE 1), BSU1 (BRIL SUPPRESSOR 1), and PP2A (PROTEIN PHOSPHATE 2A; Wang et al., 2002; He et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2011). It further results in modulation of various biological processes leading to regulation of vegetative as well as reproductive development of plants (Clouse, 2011). Studies have also reported that phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of casein kinase2 and MAPK (mitogen activated protein kinase) substrates were observed after the application of BR (Lin et al., 2015). Moreover, earlier studies have also demonstrated that BRs interact with other plant hormones to regulate the growth and development of plants (Choudhary et al., 2012). Binding of BZR1 protein to promoter regions of IAA19 and ARF7 regulates plant growth and development as a result of BR-auxin crosstalk (Zhou et al., 2013). Pollen tube cell expansion has been reported to be regulated by BR-ethylene crosstalk by modulation of FERONIA, which encodes a receptor like kinase involved in pollen tube development (Huck et al., 2003; Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007). In rice plants, enhancement in content of cytokinins was observed under drought stress after the up-regulation of BR related genes like DWF5, BAK1, BSK1, and SERK1 suggesting BRs-CKs signaling (Peleg et al., 2011). BR homeostasis is also necessary in plants for normal biological functions. It is regulated by the feedback expression of various genes involved in the biosynthesis of BRs as well as sterols (Tanaka et al., 2005). These researchers demonstrated that BZR application has been resulted in enhancing the expression of BR-biosynthetic genes like DWF4, CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS AND DWARFISM (CPD), DEETIOLATED2 (DET2), BR-6-oxidase (BR6ox1), and ROTUNDFOLIA3 (ROT3) in BR-depleted Arabidopsis plants. However, the exogenous application of BL resulted in the down-regulation of DWF4, CPD, BR6ox1, and ROT3. Esterification process by putative CoA-dependent acyltransferases encoded by DRL1 (DWARF AND ROUND LEAF-1) which plays an important role in BR homeostasis (Zhu et al., 2013).

Conclusions and future prospects

From the present study it may be concluded that seed soaking with 24-epibrassinolide recovers the impaired growth of B. juncea seedlings under imidacloprid stress by modulating the expression of genes encoding key enzymes including chlorophyllase, citrate synthase, succinyl Co-A ligase, succinate dehydrogenase, fumarate hydratase, malate synthase, phytoene synthase, chalcone synthase, and phenylalanine ammonialyase. In future studies, the expression analysis of BR specific biosynthetic genes including DWF4, CPD, DET2, BR6ox1, and ROT3 in pesticide stressed plants would help in understanding the mechanisms of BR mediated pesticide detoxification. In addition to this BRI1 silencing and studying the expression of CaM encoding genes would help in understanding the initial steps of BR signaling. Moreover, total transcriptome sequencing and microarray analysis and total phosphoproteome profiling of plants germinated from BR soaked seeds and grown in presence of pesticides could help in exploring the detailed mechanisms of BR-mitigated pesticide toxicity.

Author contributions

AS, ST, and MK performed the experimental work and also helped in writing of this manuscript. VK, AT, and PAl analyzed the data. RB, AT, AK, and PAh designed the experimental work, evaluated the results, and wrote and revised the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research, College of Sciences Research Centre, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for supporting the project. The authors express their sincere gratitude to Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India for providing INSPIRE fellowship to AS.

References

- Ahammed G. J., Zhou Y. H., Xia X. J., Mao W. H., Shi K., Yu J. Q. (2013). Brassinosteroid regulates secondary metabolism in tomato towards enhanced tolerance to phenanthrene. Biol. Plant. 57, 154–158. 10.1007/s10535-012-0128-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnon D. I. (1949). Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 24, 1–15. 10.1104/pp.24.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonmatin J. M., Marchand P. A., Charvet R., Moineau I., Bengsch E. R., Colin M. E. (2005). Quantification of imidacloprid uptake in maize crops. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53, 5336–5341. 10.1021/jf0479362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champa W. H., Gill M. I. S., Mahajan B. V. C., Aror N. K., Bedi S. (2015). Brassinosteroids improve quality of table grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. flame seedless. Trop. Agric. Res. 26, 368–379. 10.4038/tar.v26i2.8099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. C., Wang M. K., Chiu C. Y., Huang P. M., King H. B. (2001). Determination of low molecular weight dicarboxylic acids and organic functional groups in rhizosphere and bulk soils of Tsuga and Yushania in a temperate rain forest. Plant Soil 231, 37–44. 10.1023/A:1010347421351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li W., Lu Q., Wen X., Li H., Kuang T., et al. (2011). The xanthophyll cycle and antioxidative defense system are enhanced in the wheat hybrid subjected to high light stress J. Plant Physiol. 168, 1828–1836. 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary S. P., Yu J. Q., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K., Shinozaki K., Tran L. S. P. (2012). Benefits of brassinosteroid crosstalk. Trends Plant Sci. 17, 594–605. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse S. D. (2011). Brassinosteroid signal transduction: from receptor kinase activation to transcriptional networks regulating plant development. Plant Cell 23, 1219–1230. 10.1105/tpc.111.084475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Wen D., Fu Z., Qian H. (2014). The secretion of organic acids is also regulated by factors other than aluminum. Environ. Monit. Assess. 186, 1123–1131. 10.1007/s10661-013-3443-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Poovaiah B. W. (2005). Ca2+/calmodulin is critical for brassinosteroids biosynthesis and plant growth. Nature 437, 741–745. 10.1038/nature03973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Naggar J. B., Zidan N. E. H. A. (2013). Field evaluation of imidacloprid and thiamethoxam against sucking insects and their side effects on soil fauna. J. Plant Prot. Res. 53, 375–387. 10.2478/jppr-2013-0056 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Restrepo J. M., Huck N., Kessler S., Gagliardini V., Gheyselinck J., Yang W. C. (2007). The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male- female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science 317, 656–660. 10.1126/science.1143562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-García M. P., Vilarrasa-Blasi J., Zhiponova M., Divol F., Mora-García S., Russinova E., et al. (2011). Brassinosteroids control meristem size by promoting cell cycle progression in Arabidopsis roots. Development 138, 849–859. 10.1242/dev.057331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacham Y., Holland N., Butterfield C., Ubeda-Tomas S., Bennett M. J., Chory J., et al. (2011). Brassinosteroid perception in the epidermis controls root meristem size. Development 138, 839–848. 10.1242/dev.061804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J., Yin Y., Shui-zhang F. (2013). Brassinosteroid signaling network: implications on yield and stress tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 32, 1017–1030. 10.1007/s00299-013-1438-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz-Saad S., Azoulay T., Arazi T., Yaakov E. B., Mett A., Shiboleth Y. M., et al. (2007). Chlorophyllase is a rate-limiting enzyme in chlorophyll catabolism and is post translationally regulated. Plant Cell 19, 1007–1022. 10.1105/tpc.107.050633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat S., Hasan S. A., Yusuf M., Hayat Q., Ahmad A. (2010). Effect of 28-homobrassinolide on photosynthesis, fluorescence and antioxidant system in the presence or absence of salinity and temperature in Vigna radiata. Environ. Exp. Bot. 69, 105–112. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.03.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J. X., Gendron J. M., Sun Y., Gampala S. S., Gendron N., Sun C. Q., et al. (2005). BZR1 is a transcriptional repressor with dual roles in brassinosteroid homeostasis and growth responses. Science 307, 1634–1638. 10.1126/science.1107580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honnerova J., Rothova O., Hola D., Kocova M., Kohout L., Kvasnica M. (2010). The exogenous application of brassinosteroids to Zea mays (L) stressed by long term chilling does not affect the activities of photosystem 1 or 2. J. Plant Growth Regul. 29, 500–505. 10.1007/s00344-010-9153-027784017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huck N., Moore J. M., Federer M., Grossniklaus U. (2003). The Arabidopsis mutant feronia disrupts the female gametophytic control of pollen tube reception. Development 130, 2149–2159. 10.1242/dev.00458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillais Y., Hothorn M., Belkhadir Y., Dabi T., Nimchuk Z. L., Meyerowitz E. M., et al. (2011). Tyrosine phosphorylation controls brassinosteroids receptor activation by triggering membrane release of its kinase inhibitor. Genes Dev. 25, 232–237. 10.1101/gad.2001911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinich J. F., Mandava N. B., Todhunter J. A. (1985). Relationship of nucleic acid metabolism to brassinolide-induced responses in beans. J. Plant Physiol. 120, 207–214. 10.1016/S0176-1617(85)80107-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor D., Kaur S., Bhardwaj R. (2014). Physiological and biochemical changes in Brassica juncea plants under Cd-induced stress. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:726070. 10.1155/2014/726070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M., Shimizu S. (1985). Chlorophyll metabolism in higher plants VI. Involvement of peroxidase in chlorophyll degradation. Plant Cell Physiol. 26, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Kilic S., Duran R. E., Coskun Y. (2015). Morphological and physiological responses of maize (Zea mays L.) seeds grown under increasing concentrations of chlorantraniliprole insecticide. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 24, 1069–1075. 10.15244/pjoes/31339 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ko A. Y., Rahman M. M., Abd El-Aty A. M., Jang J., Park J. H., Cho S. K., et al. (2014). Development of a simple extraction and oxidation procedure for the residue analysis of imidacloprid and its metabolites in lettuce using gas chromatography. Food Chem. 148, 402–409. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkina L. G. (2007). Phenylpropanoids as naturally occurring antioxidants: from plant defense to human health. Cell Mol. Biol. 53, 15–25. 10.1170/T772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V., Sharma A., Chawla A., Bhardwaj R., Thukral A. K. (2016). Water quality assessment of river Beas, India, using multivariate and remote sensing techniques. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 137. 10.1007/s10661-016-5141-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence J. F. (1990). Determination of total xanthophyll and marigold oleoresin. J. Ass. Off. Anal. Chem. 2, 970–975. [Google Scholar]

- Lehninger A. L., Nelson D. L., Cox M. M. (2008). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 5th Edn. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Li X. F., Ma J. F., Matsumoto H. (2000). Pattern of aluminum-induced secretion of organic acids differs between rye and wheat. Plant Physiol. 123, 1537–1544. 10.1104/pp.123.4.1537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. L., Hsu C. L., Hu C. W., Ko S. Y., Hsieh H. L., Huang H. C., et al. (2015). Integrating phosphoproteomics and bioinformatics to study brassinosteroid-regulated phosphorylation dynamics in Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics 16:533. 10.1186/s12864-015-1753-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan L. Y., Zhang Z. W., Xi Z. M., Huo S. S., Ma L. N. (2013). Brassinosteroids regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in the ripening of grape berries. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 34, 196–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. F. (2000). Role of organic acids in detoxification of aluminum in higher plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 383–390. 10.1093/pcp/41.4.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancinelli A. L. (1984). Photoregulation of anthocyanin synthesis VIII. Effect of light pretreatments. Plant Physiol. 75, 447–453. 10.1104/pp.75.2.447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakabayashi R., Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Urano K., Suzuki M., Yamada Y., Nishizawa T., et al. (2014). Enhancement of oxidative and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis by overaccumulation of antioxidant flavonoids. Plant J. 77, 367–379. 10.1111/tpj.12388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M. H., Kim H. S., Wu X., Clouse S. D., Zielinski R. E., Huber S. C. (2012). Calcium/calmodulin inhibition of the Arabidopsis BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 1 receptor kinase provides a possible link between calcium and brassinosteroid signalling. Biochem. J. 443, 515–523. 10.1042/BJ20111871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parida A., Dam A. B., Dam P. (2002). NaCl stress causes changes in photosynthetic pigments proteins and other metabolic components in the leaves of a true mangrove Bruguiera parviflora in hydroponic cultures. J. Plant Biol. 45, 28–36. 10.1007/BF03030429 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg Z., Reguera M., Tumimbang E., Walia H., Blumwald E. (2011). Cytokinin-mediated source/sink modifications improve drought tolerance and increase grain yield in rice under water-stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9, 747–758. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00584.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna M., Hernández F., Coll F., Coll Y., Amorós A. (2013). Effects of brassinosteroid analogues on total phenols, antioxidant activity, sugars, organic acids and yield of field grown endive (Cichorium endivia L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 1765–1771. 10.1002/jsfa.5968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Bhardwaj R., Kumar V., Thukral A. K. (2016c). GC-MS studies reveal stimulated pesticide detoxification by brassinolide application in Brassica juncea L. plants. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 14518–14525. 10.1007/s11356-016-6650-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Kumar V., Bhardwaj R., Thukral A. K. (2016d). Seed pre-soaking with 24-epibrassinolide reduces the imidacloprid pesticide residues in green pods of Brassica juncea L. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 1–9. 10.1080/02772248.2016.1146955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Kumar V., Singh R., Thukral A. K., Bhardwaj R. (2016b). Effect of seed pre-soaking with 24-epibrassinolide on growth and photosynthetic parameters of Brassica juncea L. in imidacloprid soil. Ecotoxicol. Env. Saf. 133, 195–201. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Kumar V., Thukral A. K., Bhardwaj R. (2016a). Epibrassinolide-imidacloprid interaction enhances non-enzymatic antioxidants in Brassica juncea L. Ind. J. Plant Physiol. 21, 70–75. 10.1007/s40502-016-0203-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma I., Bhardwaj R., Pati P. K. (2012). Mitigation of adverse effects of chlorpyrifos by 24-epibrassinolide and analysis of stress markers in a rice variety Pusa Basmati-1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 85, 72–81. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma I., Bhardwaj R., Pati P. K. (2013). Stress modulation response of 24-epibrassinolide against imidacloprid in an elite indica rice variety Pusa Basmati-1. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 105, 144–153. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma I., Bhardwaj R., Pati P. K. (2015). Exogenous application of 28-homobrassinolide modulates the dynamics of salt and pesticides induced stress responses in an elite rice variety Pusa Basmati-1. J. Plant Growth Regul. 34, 509–518. 10.1007/s00344-015-9486-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui Z. S., Ahmed S. (2006). Combined effects of pesticide on growth and nutritive composition of soybean plants. Pak. J. Bot. 38, 721–733. [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Singh N. B., Singh A., Hussain I., Yadav V. (2016). Physiological and biochemical effects of salicylic acid on Pisum sativum exposed to isoproturon. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 62, 1425–1436. 10.1080/03650340.2016.1144926 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton V. L., Rossi J. A. (1965). Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 16, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Li Q., Zhai H. (2012). Photosynthesis and growth responses of grapevine to acetochlor and fluoroglycofen. Pesti. Biochem. Physiol. 103, 210–218. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2012.05.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K., Asami T., Yoshida S., Nakamura Y., Matsuo T., Okamoto S. (2005). Brassinosteroid homeostasis in Arabidopsis is ensured by feedback expressions of multiple genes involved in its metabolism. Plant Physiol. 138, 1117–1125. 10.1104/pp.104.058040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timpa J. D., Burke J. J., Quisenberry J. E., Wendt C. W. (1986). Effects of water stress on the organic acid and carbohydrate compositions of cotton plants. Plant Physiol. 82, 724–728. 10.1104/pp.82.3.724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardhini B. V., Anjum N. A. (2015). Brassinosteroids make plant life easier under abiotic stresses mainly by modulating major components of antioxidant defense system. Front. Environ. Sci. 2:67 10.3389/fenvs.2014.00067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Y., Nakano T., Gendron J., He J., Chen M., Vafeados D., et al. (2002). Nuclearlocalized BZR1 mediates brassinosteroid-induced growth and feedback suppression of brassinosteroid biosynthesis. Dev. Cell 2, 505–513. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00153-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z. M., Zhang Z. W., Huo S. S., Luan L. Y., Gao X., Ma L. N., et al. (2013). Regulating the secondary metabolism in grape berry using exogenous 24-epibrassinolide for enhanced phenolics content and antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 141, 3056–3065. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.05.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. J., Huang Y. Y., Wang L., Huang L. F., Yu Y. L., Zhou Y. H., et al. (2006). Pesticides-induced depression of photosynthesis was alleviated by 24-epibrassinolide pretreatment in Cucumis sativus L. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 86, 42–48. 10.1016/j.pestbp.2006.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia X. J., Zhang Y., Wu J. X., Wang J. T., Zhou Y. H., Shi K., et al. (2009). Brassinosteroids promote metabolism of pesticides in cucumber. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 8406–8413. 10.1021/jf901915a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Yang C., Wang X. (2011). Brassinosteroids can regulate cellulose biosynthesis by controlling the expression of CESA genes in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 495–506. 10.1093/jxb/err164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye H., Li L., Yin Y. (2011). Recent advances in the regulation of brassinosteroid signaling and biosynthesis pathways. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 53, 455–468. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y., Vafeados D., Tao Y., Yoshida S., Asami T., Chory J. (2005). A new class of transcription factors mediates brassinosteroid-regulated gene expression in Arabidopsis. Cell 120, 249–259. 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan L. B., Peng Z. H., Zhi T. T., Zho Z., Liu Y., Zhu Q., et al. (2015). Brassinosteroid enhances cytokinin-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings. Biol. Plant. 59, 99–105. 10.1007/s10535-014-0472-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Y., Song L., Xue H. W. (2013). brassinosteroids regulate the differential growth of Arabidopsis hypocotyls through auxin signaling components IAA19 and ARF7. Mol. Plant 6, 887–904. 10.1093/mp/sss123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Xia X., Yu G., Wang J., Wu J., Wang M., et al. (2015). Brassinosteroids play a critical role in the regulation of pesticide metabolism in crop plants. Sci Rep. 5:9018. 10.1038/srep09018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Wang H., Fujioka S., Zhou T., Tian H., Tian W. (2013). Homeostasis of brassinosteroids regulated by DRL1, a putative acyltransferase in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 6, 546–558. 10.1093/mp/sss144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]