Abstract

Cesium dihydrogen phosphate (CsH2PO4, CDP) and dodecaphosphotungstic acid (H3PW12O40·nH2O, WPA·nH2O) were mechanochemically milled to synthesize CDP–WPA composites. The ionic conductivities of these composites were measured by an ac impedance method under anhydrous conditions. Despite the synthesis temperatures being much lower than the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of CDP under anhydrous conditions, the ionic conductivities of the studied composites increased significantly. The highest ionic conductivity of 6.58×10−4 Scm−1 was achieved for the 95CDP·5WPA composite electrolyte at 170 °C under anhydrous conditions. The ionic conduction was probably induced in the percolated interfacial phase between CDP and WPA. The phenomenon of high ionic conduction differs for the CDP–WPA composite and pure CDP or pure WPA under anhydrous conditions. The newly developed hydrogen interaction between CDP and WPA supports anhydrous proton conduction in the composites.

Keywords: dry fuel cell, inorganic solid acid, cesium dihydrogen phosphate, phosphotungstic acid, advanced composite

Introduction

Inorganic solid acids, such as sulfates and phosphates, have been widely studied for their application in proton exchange fuel cells because of their high proton conductivities and phase transition to superprotonic states [1–3]. Among the inorganic solid acids under active development, cesium dihydrogen phosphate (CsH2PO4, CDP) has attracted much attention owing to its ability to maintain high proton conductivity at temperatures above 230 °C, at which temperature it transforms from a monoclinic to a tetragonal structure. It has also shown promising fuel cell performance in both hydrogen and direct alcohol systems [4–6]. However, CDP retains its thermally stable superprotonic phase only under hydrous condition, for example, in a gaseous 30 mol.% H2O/Ar mixture [7]. While CDP should be heated to above 230 °C to induce high conductivity, it dehydrates and decomposes into metaphosphate (CsPO3) at temperatures above 200 °C [8]. This dehydration can be suppressed by maintaining sufficient humidity in the fuel cell systems, but it becomes a problem when scaling up the system.

In contrast, partly Cs+-substituted heteropoly acids (Cs-HPAs) have attracted significant attention owing to their higher catalytic activity with better chemical stabilities than pristine HPAs in many acid-type reactions [9]. Such Cs-HPAs are generally prepared by precipitation from aqueous solutions [10, 11]. On the other hand, we have shown that a solid-state reaction involving mechanochemical treatment using a high-energy ball mill is a promising method of improving the proton conductivity of inorganic solid acids and of synthesizing a new class of inorganic solid acid-based composites [12, 13]. When mixtures of cesium hydrogen sulfate (CsHSO4, CHS) and phosphotungstic acid (H3PW12O40, WPA) were mechanochemically milled, CsxH3−xPW12O40 was formed, which shows proton conductivity two to five orders of magnitude higher than that of the raw substances under anhydrous condition.

Recently, it has been reported that the proton conductivity of CDP is increased by introducing silica nanoparticles, especially at temperatures below the phase-transition temperature under hydrous condition [7, 14, 15]. However, high proton conductivity of CDP under anhydrous condition has not been reported to the best of our knowledge. In this study, CDP and WPA were mechanochemically milled to obtain CDP–WPA composites, aiming to produce electrolytes with high proton conductivity over a wide temperature range and under anhydrous condition for application to fuel cells. The CDP–WPA composites were characterized in term of their thermal stability and structural and electrochemical properties.

Experimental details

Reagent-grade CsH2PO4 (CDP) and H3PW12O40·nH2O (WPA·nH2O) were purchased from Soekawa Chemical Co. Ltd and Wako Pure Chemical Industries, respectively, and used as starting materials for the synthesis of various CDP–WPA composites. Prior to mechanochemical milling, WPA·nH2O was kept at 60 °C for about a day to remove the physisorbed water and obtain WPA·6H2O.

The mechanochemical milling of CsH2PO4 and WPA·6H2O was carried out for various compositions, in dry nitrogen atmosphere, using a planetary ball mill (Fritsch Pulverisette 7). Agate was selected as the material for the pot and the ball. The rotation speeds of the milling pot and table were maintained at 720 rpm with a constant rotation ratio of 1:1, and the milling was carried out for 10 min. The volume of the pot was 45 ml and 10 balls of 10 mm diameter were used for the milling. The sample weight was fixed at 2.0 g. Composites with the ratio xCDP·(100−x)WPA were prepared, where x was varied between 50 and 95 mol.%.

Powder x-ray diffraction (XRD; Ultima IV, Rigaku) patterns of the mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x) WPA composite powders were recorded at room temperature (RT) using a Cu Kα radiation source.

Fourier transform Raman (FT Raman; NRS-3100, Jasco) spectra were measured in the range of 115–1220 cm−1, using a 532 nm laser for excitation and a concave glass substrate. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR; 3100 FT-IR, Varian) spectra were recorded between 400 and 4000 cm−1 using KBr pellets.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; Thermo plus DSC 8230, Rigaku) was carried out to determine the phase-transition behavior of CDP–WPA composites. The samples were heated from RT to 300 °C at a rate of 10 °C min−1 in air.

The temperature dependence of powder XRD patterns was studied using in situ XRD-DSC (Ultima IV-Thermoplus EVO II, Rigaku) technique in dry nitrogen atmosphere. The XRD pattern was scanned between 20 and 30° at a rate of 2° min−1, and the temperature was varied between 50 and 180 °C at a rate of 2 °C min−1 for 3 cycles.

Solid proton magic-angle-spinning nuclear magnetic resonance (1H MAS NMR; UNITY-400P, VARIAN) measurements were carried out at RT using a typical single pulse sequence. The sample spinning rate was 5 kHz. The frequency scale was calibrated using neat tetramethylsilane (TMS) after adjusting the signal of adamantine spinning at 8.0 kHz to 1.87 parts per million (ppm). Sample powders for the MAS NMR measurements were dried at 170 °C in vacuum for 3 h and filled into a MAS rotor in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

Proton conductivity of the CDP–WPA composite was evaluated by ac impedance spectroscopy over a frequency range of 1–107 Hz using SI 1260-based system (Solartron). For proton conductivity measurement, pellets (13 mm in diameter) were prepared by pressing the synthesized composite powders at 60 MPa for 10 min. Before the compression, carbon sheets were placed on both sides of the composite powder to form electrodes. The proton conductivity, σ, of the sample was calculated from the impedance data as σ=d/RS, where d and S are the thickness and face area of the sample, respectively. R was derived from the low intersect of the high-frequency semicircle on the complex impedance plane with the real Re(Z) axis. For each set of measurement conditions, all composite electrolytes were equilibrated for 1 h before measuring the conductivity.

Results and discussion

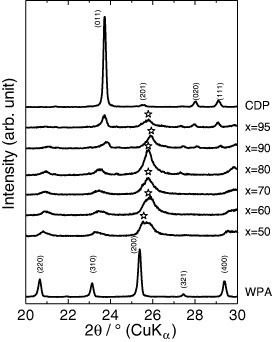

Figure 1 shows powder XRD patterns of various xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites. The diffraction peaks of CDP (topmost in figure 1) and WPA·6H2O (bottom) were obvious before milling, whereas after milling for 10 min, large changes were observed in the XRD patterns around 25–26°. The diffraction peak at 25.5° with the highest intensity for WPA shifted to higher angles in the composites, indicating that H+ ion in WPA was partly substituted with Cs+ ion to form CsxH3−xPW12O40 upon mechanochemical milling. The XRD patterns of the composites are quite different from those of CDP. For CDP, a monoclinic phase was observed with the main peak at 23.7°. Most peaks in CDP-WPA composites can be assigned to WPA, and the main peak of CDP appears in the composites with x=90 and 95. This result suggests a decrease in the interplanar spacing (d) of the Keggin unit of WPA for these composites owing to the electrostatic compaction induced by the introduction of large Cs+ cations into WPA [16, 17].

Figure 1.

Powder XRD patterns of CDP, WPA and mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites (720 rpm for 10 min in dry nitrogen atmosphere).

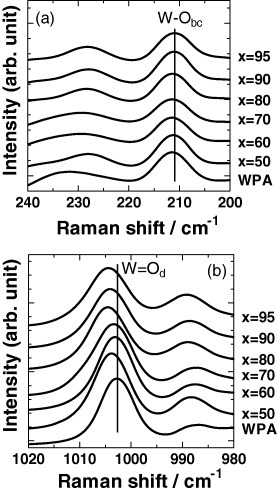

Structural changes in the xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites were also observed by FT Raman and FTIR spectroscopies. Intense bands in the FT Raman spectrum of WPA (figure 2) at 211 and 1003 cm−1 were assigned to W–Obc (corner- and edge-shared W–O–W) and  (terminal

(terminal  ) modes, respectively. Upon milling of CDP with WPA, the W–Obc Raman band was not changed, whereas the

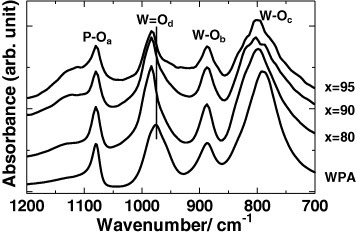

) modes, respectively. Upon milling of CDP with WPA, the W–Obc Raman band was not changed, whereas the  band shifted significantly to high frequencies with increasing x. These features were clarified in the FTIR spectra in figure 3. Bands at 786, 885, 976 and 1080 cm−1 are attributed to W–Oc (edge-shared W–O–W), W–Ob (corner-shared W–O–W),

band shifted significantly to high frequencies with increasing x. These features were clarified in the FTIR spectra in figure 3. Bands at 786, 885, 976 and 1080 cm−1 are attributed to W–Oc (edge-shared W–O–W), W–Ob (corner-shared W–O–W),  (terminal

(terminal  ) and P–Oa vibrations in WPA, respectively [18]. The

) and P–Oa vibrations in WPA, respectively [18]. The  IR band shifted significantly to high frequency, especially for x ≽ 80, which is similar to the Raman results. These observations indicate shortening of the

IR band shifted significantly to high frequency, especially for x ≽ 80, which is similar to the Raman results. These observations indicate shortening of the  bond in WPA for these composites owing to the electrostatic compaction induced by introducing relatively large Cs+ cations into WPA.

bond in WPA for these composites owing to the electrostatic compaction induced by introducing relatively large Cs+ cations into WPA.

2.

FT Raman spectra of WPA and mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites.

3.

FTIR absorption spectra of WPA and mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites.

We have already reported similar changes in the crystalline and chemical structures of mechanochemically synthesized CHS–WPA composites [16, 17]. Although the Cs+ ion source of CHS–WPA systems is clearly different from that in this study, both composite systems showed very similar changes in diffraction patterns, especially a shift of the main peak of WPA to a higher angle compared with that of pure WPA. These observations imply that a solid-state reaction induced by mechanochemical treatment is a promising method of synthesizing a new class of inorganic solid acid-based composites.

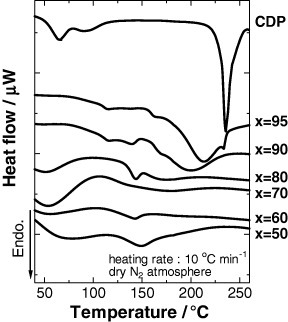

The thermal properties of CDP and xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites were evaluated by DSC as shown in figure 4. A significant endothermic peak was observed at 235 °C for pure CDP in dry nitrogen atmosphere and associated with the dehydration of CDP. The DSC spectrum changed significantly for composite systems: after mechanochemical milling, the dehydration peak of CDP split, broadened and shifted to lower temperatures with decreasing x; it almost disappeared for the composites with x ⩽ 80. These observations imply the formation of a disordered state in composites due to the chemical interaction between CDP and WPA induced by mechanochemical milling [14].

4.

DSC curves of CDP and mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites measured in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

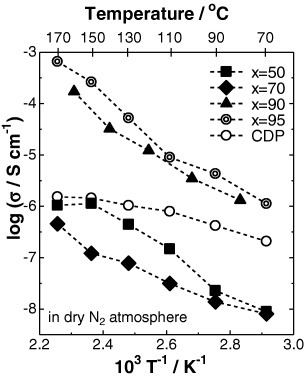

Changes in the proton conductivity of the xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites were measured on cooling from 170 to 70 °C, which is below the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of CDP. Figure 5 shows proton conductivity as a function of temperature for xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites in dry nitrogen atmosphere. The ionic conductivity of CDP was changed markedly with the addition of WPA, and the highest ionic conductivity of 6.58×10−4 Scm−1 was achieved for the 95CDP·5WPA composite electrolyte at 170 °C in dry nitrogen atmosphere. It is noteworthy that the CDP composite electrolyte containing a small amount of WPA has conductivity one to three orders of magnitude higher than that of pure CDP under anhydrous condition. This increase is probably related to not only the wetting of CDP by hydrate in WPA but also the newly formed hydrogen bonds between CDP and WPA. On the other hand, the ionic conductivity is lower in composite electrolytes with x ⩽ 70 than in CDP. Probably the high WPA content acted as a barrier for proton transfer and hindered ionic conduction via the so-called ‘geometrical effect’ [19, 20].

5.

Temperature dependence of conductivity of xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

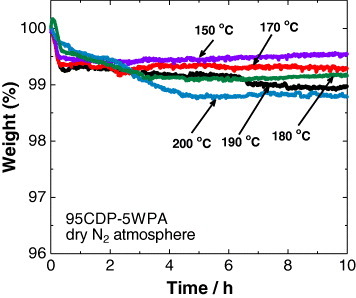

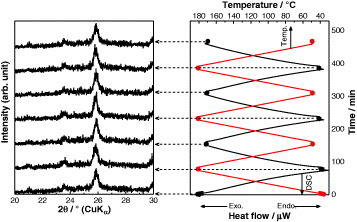

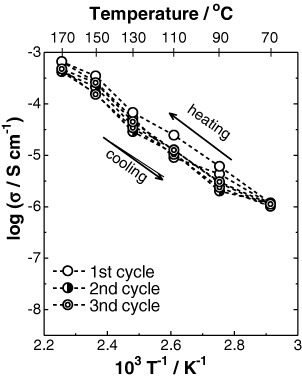

The thermal stability was evaluated in dry nitrogen atmosphere for 95CDP·5WPA composite (figure 6) and was acceptable up to 180 °C for 10 h. A slight weight loss (about 0.2 wt.%) occurred at 190 °C after the evaporation of adsorbed water, and a considerable weight loss due to dehydration of the composite was observed at 200 °C. The corresponding powder XRD pattern (figure 7) was unchanged between 50 and 180 °C in dry nitrogen atmosphere for 3 cycles, revealing the lack of structural changes in this temperature range. The proton conductivity of the 95CDP·5WPA composite in dry nitrogen atmosphere was studied between 50 and 170 °C for 3 cycles (figure 8). A small hysteresis was observed and attributed to the dissimilar initial conditions for various cycles—the conductivity was slightly higher in the first cycle due to the physisorbed water. From the thermal analyses, we expect that the high proton conductivity of 95CDP·5WPA composite can long be maintained at temperatures up to 180 °C under anhydrous condition.

6.

Thermal stability of 95CDP·5WPA composite at different temperatures in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

7.

XRD–DSC patterns of 95CDP·5WPA composite in a temperature range of 50–180 °C in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

8.

Temperature dependences of proton conductivity of 95CDP·5WPA composite for 3 cycles in dry nitrogen atmosphere.

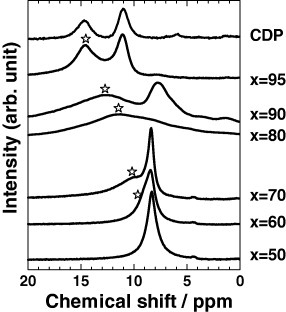

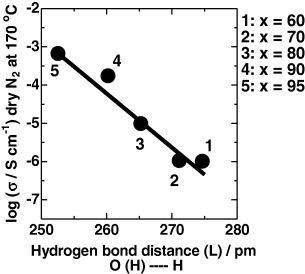

Figure 9 shows the 1H MAS NMR spectra of mechanochemically milled xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites. All the samples were dried at 170 °C in vacuum for 3 h to remove adsorbed water prior to the measurements. Two broad signals are observed for pure CDP at 11.04 and 14.70 ppm and can be ascribed to mobile protons in CDP. After mechanochemical milling, the signals progressively shifted to lower magnetic fields with increasing x indicating a higher hydrogen bonding strength [21]. From these results, the hydrogen bonding distance (L) between OH in CDP and Od in WPA was estimated using the relation L=100×(79.05−δiso)/25.5, where δiso is the 1H chemical shift (denoted by  ) expressed in ppm with respect to the TMS signal [22, 23]. Figure 10 shows the relationship for xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites between L and proton conductivity in dry nitrogen atmosphere at 170 °C, i.e. below the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of CDP. For the mechanochemically milled CDP–WPA composite system, the proton conductivity in dry nitrogen atmosphere showed a good correlation with the hydrogen bond distance (O (H) … H). Thus, the shortening of the hydrogen bond distance affects the proton conductivity of the CDP–WPA composites.

) expressed in ppm with respect to the TMS signal [22, 23]. Figure 10 shows the relationship for xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites between L and proton conductivity in dry nitrogen atmosphere at 170 °C, i.e. below the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of CDP. For the mechanochemically milled CDP–WPA composite system, the proton conductivity in dry nitrogen atmosphere showed a good correlation with the hydrogen bond distance (O (H) … H). Thus, the shortening of the hydrogen bond distance affects the proton conductivity of the CDP–WPA composites.

9.

1H NMR spectra of xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites.

10.

Relationship between hydrogen bond distance (L) and proton conductivity at 170 °C in dry N2 atmosphere for xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites; L was calculated as L=100×(79.05−δiso)/25.5, where δiso is the 1H chemical shift (denoted by  in figure 9).

in figure 9).

Previously, we found that the mechanochemically synthesized CHS–WPA composites exhibit high proton conductivity under anhydrous condition, and better water stability than their raw substances [16, 17]. Nevertheless, the catalyzed reduction of sulfate solid acids under hydrogen atmosphere may degrade the electrochemical performance during fuel cell operation [24]. On the other hand, CDP requires a certain level of humidity to achieve high proton conductivity, whereas the phosphate solid acid is not reduced to form solid phosphorus or gaseous HxP species [4]. Therefore, improvement of proton conductivity of CDP under anhydrous condition is important for fuel cell design.

In this study, the CDP–WPA composites consisted of a bulky phase and an interfacial phase. XRD and spectral results suggest that a disordered CDP structure was produced at the surface and/or inside of WPA particles. This well-dispersed disordered CDP phase can form ionic percolation pathways via the interfacial phase. Even at much lower temperatures than the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of CDP under anhydrous condition, the ionic percolation can be induced in such interfacial phase, improving protonic conduction. This phenomenon is superior to the protonic conduction behavior of pure CDP under anhydrous condition, especially at low temperatures.

Conclusions

Solid acid xCDP·(100−x)WPA composites were synthesized by mechanochemical milling. The powder XRD patterns and spectral measurements indicated that the H+ ions in WPA were partly substituted by Cs+ cations with relatively large ionic radius to form CsxH3−xPW12O40 owing to the compaction by mechanochemical milling. The protonic conductivity under anhydrous condition was improved at temperatures lower than the dehydration and phase-transition temperatures of pure CDP. Ionic percolation for composite systems will be induced in the interfacial phase between CDP and WPA, improving protonic conduction. Mechanochemically synthesized CDP–WPA composite electrolytes are superior to pure CDP or WPA.

Acknowledgment

This work was partly supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas No. 439 ‘Nanoionics,’ A02 No. 19017009), by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Challenging Exploratory Research No. 21655075) and by The Murata Science Foundation.

References

- Baranov A I, Shuvalov L A. and Shchagina N M. JETP Lett. 1982;36:459. [Google Scholar]

- Norby T. Solid State Ion. 1999;125:1. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2738(99)00152-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suwa Y, Yamauchi J, Kageshima H. and Tsuneyuki S. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2001;79(B):31. doi: 10.1016/S0921-5107(00)00539-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boysen D A, Uda T, Chisholm C R I. and Haile S M. Science. 2004;303:68. doi: 10.1126/science.1090920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uda T. and Haile S M. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2005;8:A245. doi: 10.1149/1.1883874. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uda T, Boysen D A, Chisholm C R I. and Haile S M. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2006;9:A261. doi: 10.1149/1.2188069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otomo J, Minagawa N, Wen C J, Eguchi K. and Takahashi H. Solid State Ion. 2003;156:357. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2738(02)00746-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taninouchi Y, Uda T, Awakura Y, Ikeda A. and Haile S M. J. Mater. Chem. 2007;17:3182. doi: 10.1039/b704558c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara T, Mizuno N. and Misono M. Adv. Catal. 1996;41:113. doi: 10.1016/S0360-0564(08)60041-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okuhara T, Watanabe H, Nishimura T, Inumaru K. and Misono M. Chem. Mater. 2000;12:2230. doi: 10.1021/cm9907561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimharao K, Brown D R, Lee A F, Newman A D, Siril P F, Tavener S J. and Wilson K. J. Catal. 2007;248:226. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2007.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A, Tezuka T, Nono Y, Tadanaga K, Minami T. and Tatsumisago M. Solid State Ion. 2005;176:2899. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2005.09.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A, Kikuchi T, Katagiri K, Muto H. and Sakai M. Solid State Ion. 2006;177:2421. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2006.03.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponomareva V G. and Shutova E S. Solid State Ion. 2007;178:729. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2007.02.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Otomo J, Ishigooka T, Kitano T, Takahashi H. and Nagamoto H. Electrochim. Acta. 2008;53:8186. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2008.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A, Kikuchi T, Katagiri K, Daiko Y, Muto H. and Sakai M. Solid State Ion. 2007;178:723. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2007.02.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daiko Y, Takagi H, Katagiri K, Muto H, Sakai M. and Matsuda A. Solid State Ion. 2008;179:1174. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2008.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y S, Wang F, Hickner M, Zawodzinski T A. and McGrath J E. J. Membr. Sci. 2003;212:263. doi: 10.1016/S0376-7388(02)00507-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuer K D. Chem. Mater. 1996;8:610. doi: 10.1021/cm950192a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuer K D, Fuchs A, Ise M, Spaeth M. and Maier J. Electrochim. Acta. 1998;43:1281. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(97)10031-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A, Nguyen V H, Daiko Y, Muto H. and Sakai M. Solid State Ion. 2010;181:180. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2008.12.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert H, Yesinowski J P, Silver L A. and Stolper E M. J. Phys. Chem. 1988;92:2055. doi: 10.1021/j100318a070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Yanagisawa M. and Hayamizu K. Anal. Sci. 1991;7:955. doi: 10.2116/analsci.7.955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haile S M, Boysen D A, Chisholm C R I. and Merie R B. Nature. 2001;410:910. doi: 10.1038/35073536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]