Abstract

BRCA1 mutations strongly predispose affected individuals to breast and ovarian cancer, but the mechanism by which BRCA1 acts as a tumor suppressor is not fully understood. Homozygous deletion of exon 2 of the mouse Brca1 gene normally causes embryonic lethality, but we show that exon 2‐deleted alleles of Brca1 are expressed as a mutant isoform that lacks the N‐terminal RING domain. This “RING‐less” BRCA1 protein is stable and efficiently recruited to the sites of DNA damage. Surprisingly, robust RAD51 foci form in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1 in response to DNA damage, but the cells nonetheless display the substantial genomic instability. Genomic instability can be rescued by the deletion of Trp53bp1, which encodes the DNA damage response factor 53BP1, and mice expressing RING‐less BRCA1 do not show an increased susceptibility to tumors in the absence of 53BP1. Genomic instability in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1 correlates with the loss of BARD1 and a defect in restart of replication forks after hydroxyurea treatment, suggesting a role of BRCA1–BARD1 in genomic integrity that is independent of RAD51 loading.

Keywords: cancer, DNA repair, genomic integrity, mouse models, RAD51

Subject Categories: DNA Replication, Repair & Recombination

Introduction

Mutations in the BRCA1 gene account for approximately 7% of human hereditary breast and ovarian cancer cases, and mutation of the Brca1 gene also causes cancer in mice 1, 2. Despite the importance of BRCA1 mutations in human disease, the precise mechanism by which BRCA1 mediates DNA repair is still unclear. Cells lacking functional BRCA1 often show a defect in the homologous recombination (HR) pathway for the repair of DNA double‐strand breaks (DSBs) 2, 3. This defect leads to genomic instability in BRCA1‐deficient cells and contributes to tumorigenesis.

Recent research efforts have aimed to determine which of the conserved domains within the BRCA1 protein are most important for its activity. The N‐terminal RING domain forms a heterodimer with BRCA1‐Associated RING Domain protein 1 (BARD1) that acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase 4, 5, 6. E3 ligase activity of BRCA1–BARD1 may contribute to genomic integrity by ubiquitylating chromatin at repetitive satellite DNA elements, which keeps these regions in a transcriptionally silent state 7. Other mouse models have, however, shown that the inactivation of BRCA1's ability to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase has a negligible effect on tumor suppressor activity and that the C‐terminal BRCT domains are of greater importance 8, 9. A new perspective on BRCA1's cellular function has come from the finding that targeting of the DNA damage response factor 53BP1 rescues many of the phenotypes associated with BRCA1 deficiency. Mice carrying homozygous mutations in Brca1 are normally not viable, but deletion of Trp53bp1, which encodes 53BP1, rescues embryonic lethality 10. Ablation of 53BP1 has been shown to normalize the rates of HR in Brca1‐deficient cells 11, 12, suggesting that 53BP1 may act to limit the use of the HR pathway for DSB repair. It is not known how BRCA1 counteracts this inhibitory effect of 53BP1 on HR.

To better understand how BRCA1 and 53BP1 regulate mammalian double‐strand break repair, we studied two mouse models of Brca1 deficiency featuring replacement or the deletion of Brca1 exon 2. These are Brca1 ex2/ex2 mice, in which exon 2 is replaced by a neo cassette, and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 mice, in which exon 2 is conditionally deleted by Cre‐loxP recombination 13, 14. We find that both of these strains express a mutant BRCA1 protein isoform that lacks the N‐terminal RING domain. This mutant BRCA1 isoform can support the accumulation of RAD51 at sites of DNA damage, although cells expressing the mutant isoform nonetheless show genomic instability and a defect in replication fork stability. These findings suggest that the RING domain of BRCA1 plays an essential role in replication fork stability that is independent of RAD51 foci formation.

Results and Discussion

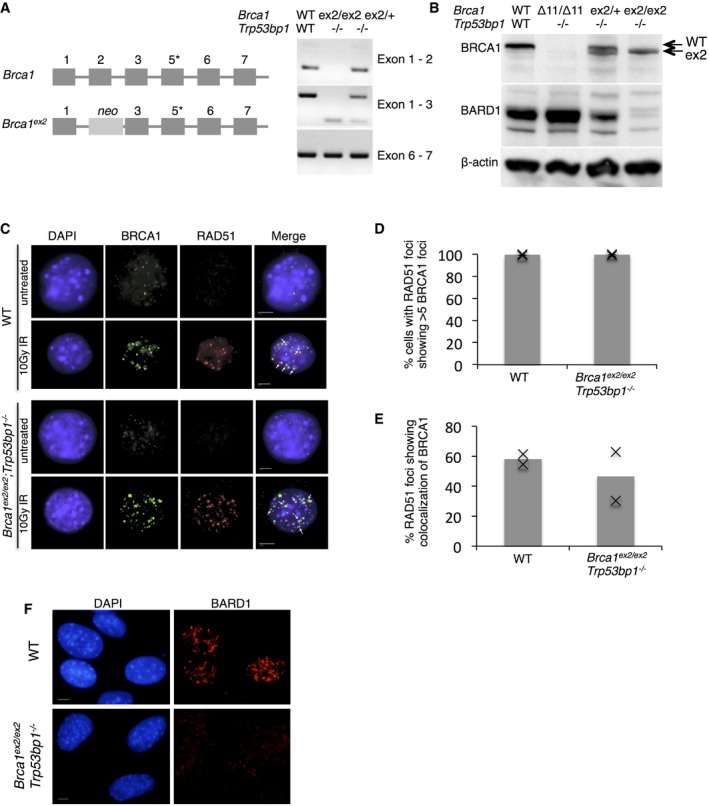

Homozygous Brca1 ex2/ex2 mice show embryonic lethality at an early stage of development 13. The start codon for translation of the full‐length BRCA1 polypeptide, which is encoded in exon 2, is deleted in the Brca1 ex2 allele (Fig 1A). The Brca1 ex2 allele has therefore been considered to be a “null” allele of Brca1 15. The early embryonic lethality of Brca1 ex2/ex2 mice can, however, be rescued by codeletion of Trp53bp1, which encodes the DNA repair factor, 53BP1 16. We prepared Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and found that these cells produce a Brca1 transcript in which exon 1 is spliced directly to exon 3 (Fig 1A). This Brca1 transcript contains all known protein‐coding exons after exon 3 and is translated to make a BRCA1 isoform that is slightly smaller than the full‐length ~220‐kDa protein (Fig 1B). Mass spectrometry showed that the start site for translation of the mutant protein is either Met‐90 or Met‐99 (which lie within the same tryptic fragment). Translation starting at either of these sites would be in the correct frame to produce a ~210‐kDa BRCA1 polypeptide, consistent with our Western blot results. The absence of the N‐terminal region means that almost all of the RING domain, which is made up of residues 1–109 in the WT protein 17, is missing from the mutant protein isoform. Instead of a null allele, Brca1 ex2 is therefore expressed as a “RING‐less” form of BRCA1.

Figure 1. Targeting of Brca1 exon 2 leads to production of a stable, N‐terminal truncated protein isoform.

- Structure of Brca1 ex2 allele. *Note that exon 4 was annotated in error in original descriptions of the gene structure and is not drawn. RT–PCR shows a novel product from the Brca1 ex2 allele, corresponding to splicing of exon 1 directly to exon 3.

- Western blot to detect BRCA1 and BARD1 in MEFs expressing WT and mutant Brca1.

- Immunofluorescent (IF) detection of BRCA1 and RAD51 at IR‐induced nuclear foci in cells expressing WT and mutant forms of Brca1. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Quantification of IF, showing the proportion of cells with RAD51 foci that also had > 5 BRCA1 foci. N = 2.

- Quantification of IF, showing the proportion of RAD51 foci that colocalized with BRCA1 foci. N = 2.

- Immunofluorescent detection of BARD1 at IR‐induced nuclear foci in MEFs expressing WT and mutant forms of Brca1. Scale bar: 10 μm.

BRCA1 and BARD1 form a heterodimer through the contacts made between their respective RING domains, and heterodimerization normally stabilizes both proteins 6, 17, 18. In Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− cells, which express RING‐less BRCA1, there is no detectable BARD1 protein (Fig 1B). In contrast, Brca1 Δ11/Δ11;Trp53bp1 −/−cells, which express a mutant BRCA1 isoform with an intact RING domain (BRCA1Δ11), showed no reduction in BARD1. RING‐less BRCA1 appears stable, presumably because the N‐terminal degron normally found within amino acids 1–167 is deleted 19. Although it cannot form a heterodimer with BARD1, robust nuclear foci of BRCA1 protein were observed in both WT and Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− cells in response to ionizing radiation (IR). These BRCA1 foci showed colocalization with RAD51 at DNA damage sites equivalent to that seen in WT cells (Fig 1C–E). Conversely, nuclear foci of BARD1 were absent in Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− cells (Fig 1F), consistent with the very low level of stable BARD1.

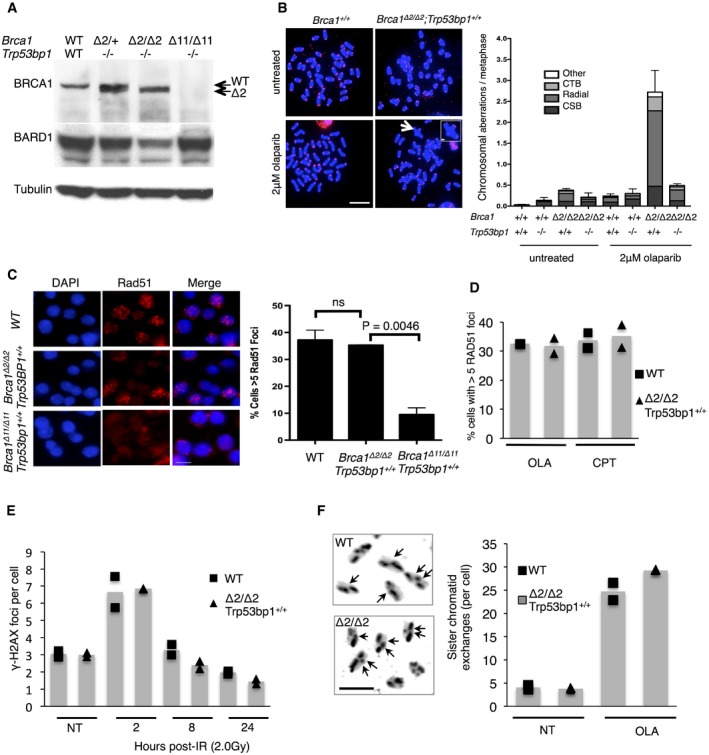

To test the activity of RING‐less BRCA1, we used mice carrying the conditional Brca1 flex2 allele, in which Brca1 exon 2 can be deleted by the expression of Cre recombinase. A previous study using these mice showed that conditional deletion of exon 2 in the mammary epithelium leads to tumor formation 14. As was the case with the Brca1 ex2 allele, Brca1 exon 2‐deleted cells (Brca1 Δ2/Δ2) express a variant ~210‐kDa protein product derived from splicing of exon 1 directly to exon 3 (Fig 2A). Levels of BARD1 are also substantially reduced in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells, consistent with a failure of the mutant, RING‐less BRCA1 isoform to stabilize BARD1 protein. The BRCA1Δ2 protein is expressed in both Trp53bp1 −/− and Trp53bp1 +/+ cells (Fig EV1A), allowing us to study the activity of RING‐less BRCA1 in cells that express 53BP1 (henceforth “Brca1 Δ2/2Δ2”). Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 B cells showed elevated rates of spontaneous chromosome aberrations and especially high rates of genomic instability after treatment with the poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase inhibitor, olaparib, which increases the frequency of DNA DSBs (Fig 2B). Hypersensitivity was also observed in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells exposed to cisplatin, which covalently crosslinks DNA and impedes replication (Fig EV1B).

Figure 2. Conditional deletion of Brca1 exon 2 causes genomic instability despite normal recruitment of RAD51 to DNA double‐strand breaks.

- Western blot showing abundance of BRCA1 and BARD1 protein in Brca1Δ2/Δ2;Trp53bp1 −/− mouse B cells.

- Analysis of chromosome aberrations in mice with targeted deletion of Brca1 exon 2 and Trp53bp1. Left, metaphase spreads were prepared from B cells treated with olaparib. Arrows show examples of chromosome aberrations. Right, quantification of chromosome breaks (CSB), chromatid‐type breaks (CTD), radial chromosomes, and other abnormalities in mouse B cells. Error bars indicate SD, N = 3. Scale bar: 100 μm.

- RAD51 foci in B cells after 10 Gy IR exposure. Chart shows mean percentage of cells with > 5 foci, N = 3. Error bars indicate SD, statistical analysis by two‐tailed Student's t‐test. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Percentage of cells showing > 5 RAD51 foci after 4‐h treatment with 10 μM olaparib (OLA) or 10 μM camptothecin (CPT). N = 2.

- Average number of γ‐H2AX foci per cell in cells that were not treated (NT) or exposed to 2 Gy ionizing radiation. N = 2.

- Sister chromatid exchanges in cells that were not treated (NT) or exposed to 2 μM olaparib (OLA) for 16 h. Black arrows in images show SCEs in olaparib‐treated cells. Scale bar: 5 μm. N = 2.

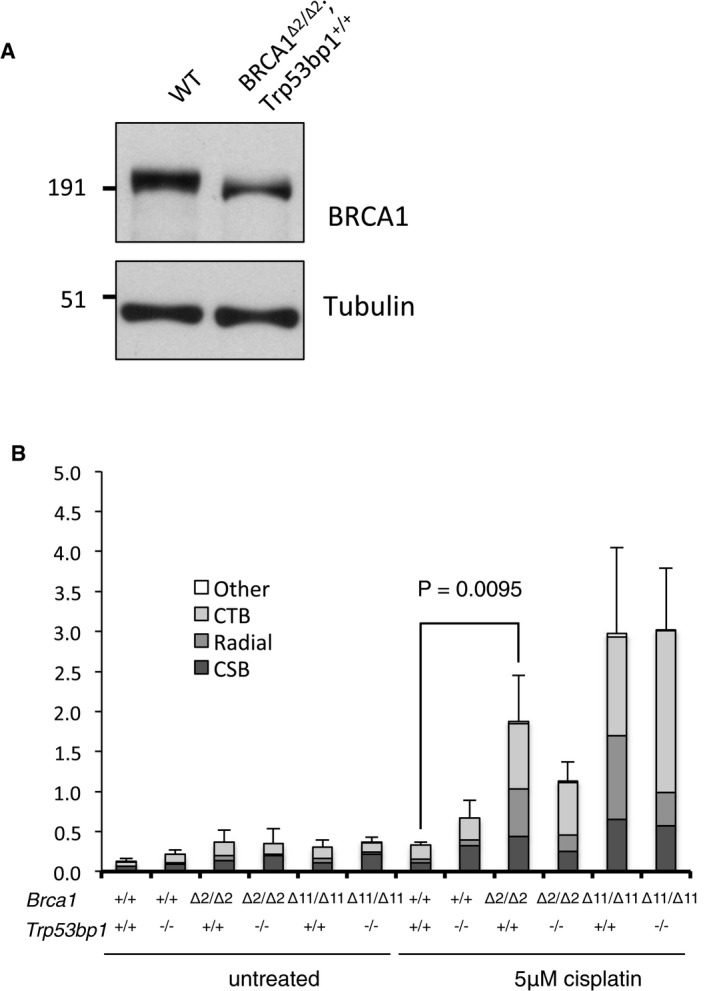

Figure EV1. Cisplatin sensitivity in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1.

- Western blot showing the expression of mutant BRCA1 isoform in BRCA1 Δ2/Δ2 ;Trp53bp1 +/+ B cells.

- Chromosome aberrations in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 and Brca1 Δ11/Δ11 mouse B cells after overnight exposure to 5 μM cisplatin. N = 3, mean frequencies of chromosome‐type breaks (CSB), single chromatid breaks (CTD), radial chromosomes, and all other chromosome aberrations (Other) are shown. Error bars show standard deviation of the mean total chromosome aberration frequency for each genotype. P‐value calculated using Student's t‐test, two‐tailed.

Surprisingly, genomic instability in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells did not correlate with a failure to form irradiation‐induced nuclear RAD51 foci, as is typically seen in other models of Brca1 deficiency such as Brca1 Δ11 or Brca1 Δ5–13 (Fig 2C) 11, 12. Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells formed IR‐induced RAD51 foci at an equivalent rate to that observed in WT cells, and also formed robust RAD51 foci after treatment with olaparib or camptothecin (Fig 2D). BRCA1 normally forms a ternary complex at break sites with PALB2 (Partner and Localizer of BRCA2) and BRCA2, which helps load RAD51 onto resected DNA ends 20. BRCA1 binds PALB2 through the association of coiled coil motifs in both proteins 21. The BRCA1 coiled coil motif is still present in RING‐less BRCA1, potentially explaining why the mutant protein is able to support RAD51 foci formation after DNA damage. Ionizing radiation‐induced γ‐H2AX foci were also resolved with equivalent kinetics in WT and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells (Fig 2E), indicating that there is no overt defect in DSB repair in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1. Finally, we tested the efficiency of homologous recombination in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells by measuring the frequency of sister chromatid exchanges (SCEs), which are formed by crossover recombination during repair of DSBs. No reduction in the frequency of spontaneous or olaparib‐induced SCEs was observed between WT and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells (Fig 2F). Taken together, these results suggest that genomic instability in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1 is not a consequence of deficient repair of DNA double‐strand breaks.

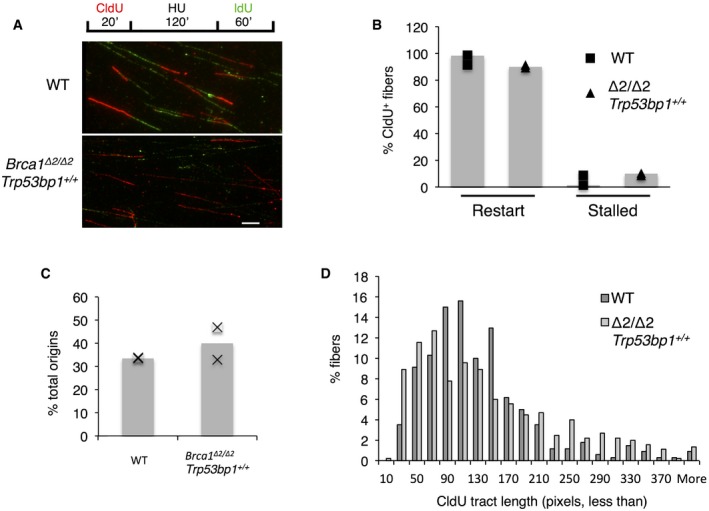

In addition to a role in mediating RAD51 assembly at DSBs, BRCA1 has been implicated in the protection of newly synthesized DNA at stalled replication forks 22. We therefore tested the stability of replication forks in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells. We used a DNA combing assay to monitor fork progression after treatment with hydroxyurea (HU), which causes fork stalling (Fig 3A). The majority of replication tracts showed restart after HU was removed, as indicated by contiguous tracts of CldU and IdU staining. In the Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells, however, there was an elevated frequency of tracts that stained for CldU only, consistent with failure to restart the replication fork after HU‐induced stalling (Fig 3B). RING‐less BRCA1 therefore appears to be deficient in facilitating recovery from replication stress, which may account for the increased genomic instability in cells expressing this mutant isoform. We also examined the rate of activation of new origins, and the length of initial replication tracts, but found no substantial difference between WT and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells (Fig 3C and D). Our results indicate that the RING domain of BRCA1, potentially in conjunction with BARD1, protects genomic integrity by enabling the restart of stalled replication forks. This role is distinct from BRCA1's role in mediating the assembly of RAD51 foci at DNA double‐strand break sites, and is consistent with recent findings that protection of replication forks can rescue genome instability in BRCA‐deficient cells without restoration of DSB repair via HR 23.

Figure 3. Replication fork stability in WT and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 ;Trp53bp1 +/+ cells.

- Experimental scheme and representative images of DNA fibers. Scale bar: 5 μm.

- Analysis of fibers showing proportions of replication forks that showed restart after HU treatment or remained stalled. N = 2, > 500 fibers scored per experiment.

- Proportion of total forks showing de novo initiation after HU treatment. N = 2, > 500 fibers scored per experiment.

- Length of initial replication fork tracts (CldU tracts). N = 2, > 200 fibers measured per experiment.

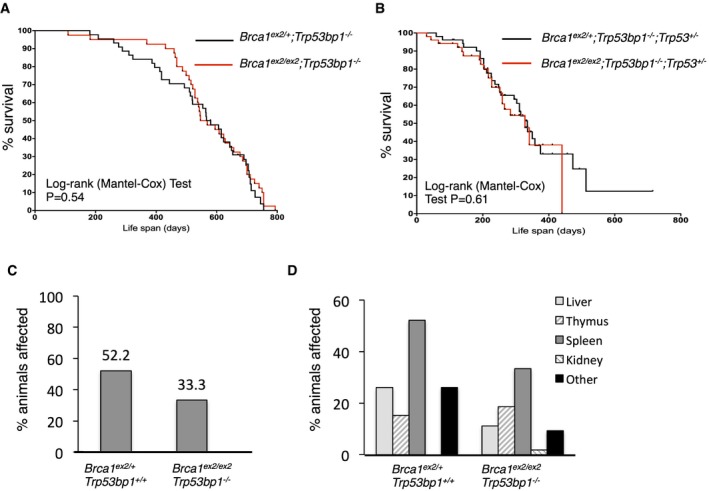

Ablation of 53BP1 rescues the embryonic lethality and genomic instability in mice carrying exon 2‐deleted forms of Brca1 (Fig 2B) 16. To test whether Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice are susceptible to tumors, we performed a longitudinal study of cohorts of Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− and Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/− animals (Fig 4A). The lifespan of the Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice was not significantly altered compared to Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/− littermates. The frequency of tumors in Brca1‐deficient mice is greatly increased in the absence of one or both copies of Trp53, which encodes the p53 tumor suppressor 24. We therefore bred additional cohorts of Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/−;Trp53 +/− and Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/−;Trp53 +/− mice to test whether loss of p53 affected survival in mice expressing RING‐less BRCA1 (Fig 4B). Although in each case the animals on a Trp53 +/− background showed a decreased survival relative to the Trp53 +/+ cohort, there was no statistically significant difference in survival between Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− ;Trp53 +/− and Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/− ;Trp53 +/− animals. A number of animals from both the Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− and Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/− cohorts showed abnormal growth affecting one or more tissues at the time of death, but there was no increase in the frequency of abnormal tissue morphology in the Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice compared to littermate controls (Fig 4C). Abnormal growth most commonly affected the spleen, consistent with lymphoma, which has previously been reported in old Trp53bp1 −/− mice (Fig 4D) 25. Expression of RING‐less BRCA1 instead of the full‐length protein therefore does not cause any increase in tumor susceptibility when 53BP1 is absent.

Figure 4. Lifespan and tumor predisposition of mice expressing RING‐less BRCA1.

- Kaplan–Meier survival curve for Brca1 ex2/+ ;Trp53bp1 −/− and Brca1 ex2/ex2 ;Trp53bp1 −/− mice. N = 20 animals in each group. Statistical analysis by Mantel–Cox log‐rank test.

- Kaplan–Meier survival curve for Brca1 ex2/+ ;Trp53bp1 −/− ;Trp53 +/− and Brca1 ex2/ex2 ;Trp53bp1 −/− ;Trp53 +/− mice. N = 20 animals in each group. Statistical analysis by Mantel–Cox log‐rank test.

- Percentage of Brca1 ex2/+ ;Trp53bp1 −/− and Brca1 ex2/ex2 ;Trp53bp1 −/− mice showing signs of abnormal tissue morphology at death. N = 46 animals inspected for Brca1 ex2/+ ;Trp53bp +/+, N = 54 animals inspected for Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/−.

- Tissues affected by abnormal growth from N = 46 Brca1 ex2/+;Trp53bp1 −/− and N = 54 Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice.

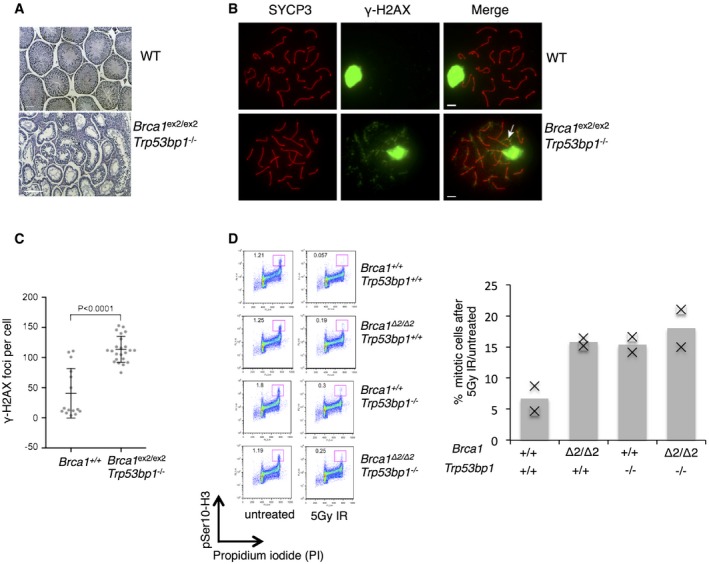

Several phenotypes of Brca1 deficiency were not rescued by Trp53bp1 deletion. Hypersensitivity of Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells to cisplatin was not relieved by Trp53bp1 deletion (Fig EV1B). This matches the phenotype of Brca1 Δ11/Δ11;Trp53bp1 −/− cells, which are also hypersensitive to cisplatin 16. Male Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice are also infertile, with reduced testis size 16. To gain further insight into the requirement for BRCA1 for normal spermatogenesis, we made sections of testes from adult male Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice. H&E staining revealed that the seminiferous tubules in Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice were markedly less populated than wild‐type tubules and showed no spermatids or spermatozoa (Fig 5A). The cellular density and identity within seminiferous tubules is consistent with arrest during the first meiotic prophase 26. To determine at which stage we observe meiotic prophase arrest, we analyzed meiotic chromosome spreads from Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes. RAD51, DMC1, and γ‐H2AX foci form normally in early meiotic prophase I Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes (data not shown), indicating that DSBs are formed with wild‐type kinetics. Chromosome pairing is for the most part normal in Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes; however, asynapsis of one or two chromosomes is observed at a higher rate than in equivalently staged wild‐type spermatocytes (56 versus 20%, P = 0.0242, Fisher's exact test, two‐tailed). Spermatogenesis in Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− mice is arrested at the pachytene stage of meiosis I (Fig 5B), likely due to a failure to form an adequate sex body, the heterochromatic region that houses the sex chromosomes and results in their transcriptional repression 27. If the sex body fails to form, sex chromosome genes are inappropriately expressed resulting in pachytene‐stage apoptosis. We observed that all of the Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes formed a nascent sex body as delineated by a region of dense γ‐H2AX staining overlapping the heteromorphic sex chromosomes (Fig 5B). However, the majority (87%) of Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes had a portion of the sex chromosomes, usually the centromeric region of the X chromosome, excluded from the sex body (arrow in Fig 5B). By contrast, only 7% of wild‐type spermatocytes exhibited a similar exclusion of a sex chromosome at early pachynema (P < 0.0001, Fisher's exact test, two‐tailed). Finally, ectopic γ‐H2AX staining was frequently observed on the autosomes of Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes (Fig 5B and C), indicating a failure to efficiently repair meiotic DSBs. The phenotypes observed for Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes are similar to that reported previously in Brca1 Δ11/Δ11;Trp53 +/− mice 28 and show that BRCA1 has an essential role in spermatogenesis that is independent of 53BP1. As Trp53bp1 −/− mice do not show a defect in spermatogenesis, this observation suggests that the RING domain of BRCA1 is required for normal spermatogenesis.

Figure 5. Arrest in spermatogenesis in mice expressing RING‐less BRCA1.

- H&E‐stained sections of seminiferous tubules from testes of WT and Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− male mice. Scale bar: 100 μm.

- Immunofluorescence on meiotic chromosomes from WT and Brca1 ex2/ex2;Trp53bp1 −/− spermatocytes. Spreads were stained for SYCP3 to indicate chromosome axes and extent of synapsis and γ‐H2AX to indicate sex body. Scale bar: 5 μm.

- Quantification of the number of γ‐H2AX foci observed at the pachytene stage in the indicated genotypes. P‐value is Mann–Whitney, two‐tailed.

- G2M checkpoint analysis in mouse B cells after IR treatment. Left, mitotic cells were identified by flow cytometry as having 4c DNA content (based on propidium iodide staining) and pSer10‐H3+. Right, quantification of flow cytometry data, showing mitotic cells after IR as the percentage of that seen in untreated cells. N ≥ 2.

Cells exposed to IR induce a checkpoint at the transition between G2 and M phase of the cell cycle, which prevents mitosis in the presence of broken chromosomes. This G2M checkpoint is deficient in cells lacking functional BRCA1 29. We measured the percentage of mitotic cells after exposure to IR and observed that WT cells showed a strong induction of the G2M checkpoint, with very few mitotic cells post‐IR, whereas Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells showed a defect in checkpoint induction (Fig 5D). This defect was not rescued in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2;Trp53bp1 −/− cells, which showed an equivalent percentage of mitotic cells after IR treatment as was seen in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2;Trp53bp1 +/+ cells. Deletion of Trp53bp1 therefore does not cause a measurable rescue of the G2M checkpoint defect of Brca1‐deficient cells, although the deletion of Trp53bp1 is by itself sufficient to cause a G2M checkpoint defect 30.

Taken together, our results suggest a more complex picture for how BRCA1 and 53BP1 collaborate to maintain the genomic integrity. Our previous work demonstrated that the deletion of Trp53bp1 rescues embryonic lethality and tumor predisposition of Brca1 Δ11/Δ11 mice by promoting the resection of DSBs, thereby facilitating homologous recombination 10, 12. Notably, the deletion of Trp53bp1 correlated with rescue of RAD51 foci formation after ionizing radiation, a hallmark of homologous recombination that is normally deficient in Brca1 Δ11/Δ11 cells. Our findings with Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells suggest that 53BP1 has an effect in regulating genomic integrity that is separable from RAD51 foci formation. Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells are capable of forming RAD51 foci, but still show genomic instability when 53BP1 is present. The defect in genomic maintenance in cells expressing RING‐less BRCA1 appears to arise during replication, suggesting that 53BP1 is also active in the control of replication fork restart. It is not clear how the RING domain of BRCA1 mediates replication fork restart. In complex with BARD1, the BRCA1 RING domain acts as an E3 ubiquitin ligase 4, which may be relevant for overcoming replication barriers or removing covalent adducts that compromise replication fork progression. On the other hand, Brca1 I26A/I26A mice, which express enzymatically deficient BRCA1, are viable and show no significant genomic instability 8, 9.

RING‐less BRCA1 has several features in common with the mutant protein expressed in Brca1 C61G/C61G mice, which are a model for the common BRCA1‐C61G patient mutation 31. The C61G mutation destabilizes the BRCA1 RING domain and prevents association with BARD1. As is the case with RING‐less BRCA1, BRCA1C61G protein is unable to maintain genomic integrity or act as a tumor suppressor, but BRCA1C61G protein can nonetheless contribute to chemoresistance of tumor cells. The ability of N‐terminal truncated isoforms of BRCA1 to partially support repair activity is of potential clinical significance. The common BRCA1 founder mutation 185delAG is a deletion of two nucleotides, which creates a premature stop codon in exon 3 and prevents the expression of full‐length BRCA1 protein. In 185delAG patient cells, BRCA1 protein expression could hypothetically be reinitiated from a downstream start codon, resulting in production of a RING‐less BRCA1 isoform, similar to that observed in Brca1 Δ2/Δ2 cells. Any such N‐terminal‐deleted BRCA1 isoforms could contribute to tumor progression or chemoresistance by facilitating a subset of DNA repair activities, especially in cells lacking 53BP1. Two recent reports have supported the idea that the expression of BRCA1185delAG can contribute to tumor chemoresistance in mouse models and human cancer cell lines 32, 33. Our results also show that the ability to form RAD51 foci may not be a reliable indicator for BRCA1 tumor suppressor activity, as mutant BRCA1 isoforms may support RAD51 foci formation, while still being unable to maintain genomic integrity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Brca1 ex2/+ mice 13 were crossed with Trp53bp1 −/− mice 34. Brca1 flex2/+ mice 14 were additionally crossed to Trp53bp1 −/− mice and CD19‐Cre mice 34. Brca1 Δ11/Δ11;Trp53bp1 −/− mice were as described 12. All animals were housed in sterile conditions under a protocol approved by the Rutgers University Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), cells were grown on sterile coverslips overnight. For B‐cell immunofluorescence, cells were applied to slides coated with CellTak (Corning). Radiation treatment to induce DSBs was 10 Gy ionizing radiation from a 137Cs source followed by 4‐h recovery at 37°C. Fixation was carried out with 2% paraformaldehyde followed by the treatment with 0.5% Triton X‐100. Antibodies used were mouse monoclonal α‐BRCA1 (aa160‐300) 36; rabbit polyclonal α‐RAD51 (Santa Cruz); rabbit polyclonal α‐BARD1 6. Fixed stained nuclei were counterstained with DAPI and imaged using a Nikon Eclipse E800 epifluorescence microscope.

Mass spectrometry

Protein lysates from activated WT and Brca1 Δ2/Δ2;Trp53bp1 −/− mouse B cells (200 μg protein each) were separated by SDS–PAGE. For each, the region predicted to contain the protein of interest (~200 kD) was excised and digested with trypsin. Digests were analyzed using a Q Exactive HF tandem mass spectrometer coupled to a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RLSCnano System (Thermo Scientific). Samples were solubilized in 5% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA and loaded on to a fused silica trap column of 100 μm × 2 cm packed with Magic C18AQ, 5 μm 200+ (Michrom Bioresources Inc, Auburn, CA). After washing for 5 min at 10 μl/min with solvent A (0.2% formic acid), the flow rate was reduced to 300 nl/min and the trap brought in‐line with a homemade analytical column (Magic C18AQ, 3 μm 200 A, 75 μm × 50 cm) for LC‐MS/MS. Peptides were eluted using a segmented linear gradient from 4 to 90% solvent B (B: 0.08% formic acid, 80% ACN): 4% B for 5 min, 4–15% B for 19 min, 15–25% B for 40 min, 25–50% B for 55 min, and 50–90% B for 8 min. Mass spectrometry data were acquired using parallel reaction monitoring targeting previously observed BRCA1_mouse tryptic peptides in the region of interest found in GPMdb (http://gpmdb.thegpm.org/) 37 as well as the potential alternative start sites for the mutant. Instrument settings were as follows: resolution 30,000 (at m/z 200); AGC target 5E5; maximum fill time 100 ms; precursor isolation window 1.4 m/z; and normalized collision energy of 25 for fragmentation. The raw files were analyzed using Xcalibur Qual browser (Thermo Fisher).

Spermatocyte chromosome spreads and immunofluorescence

Spermatocytes from mice between 2 and 6 months of age were individualized in suspension, surface‐spread, and stained for immunofluorescence as previously described 38. Identity and concentrations of antibodies used were as follows: SYCP3 (Abcam ab15093 at 1:500 and Santa Cruz sc‐74569 at 1:500); RAD51 (Calbiochem PC130 at 1:200); γ‐H2AX (Millipore JBW301, 1:10,000); MLH1 (Pharmingen 551092, 1:50). Spreads from at least two mice of each genotype were analyzed.

Preparation and hybridization of chromosome spreads

Resting B lymphocytes were isolated from mouse spleens and cultured with LPS (25 μg/ml, Sigma) and IL‐4 (5 ng/ml, Sigma) as described 12. After 36‐h growth, the cells were mock‐treated or treated with olaparib (2 μM) overnight, then arrested with 10 μg/ml colcemid for 1 h. Metaphase fixation and telomere PNA‐FISH was performed as previously described 39.

DNA combing

Splenic B cells were grown in vitro for 48 h. The cells were pulsed with CldU, HU, and IdU, and the fibers were prepared, stained, and analyzed as previously described 40.

G2M checkpoint analysis

The activated B cells were exposed to 5 Gy ionizing radiation, allowed to recover for 1 h, and then fixed with cold 70% ethanol. Staining of mitotic cells was achieved using rabbit polyclonal α‐phospho‐H3 antibody (Millipore). Cellular DNA was stained with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide, and flow cytometry data were acquired on a FACS Calibur instrument using CellQuest.

Statistics

Survival curves were plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the Mantel–Cox log‐rank test was used to evaluate the statistical differences between cohorts in the mouse aging study. Other experimental outcomes were analyzed using a two‐tailed Student's t‐test. A P‐value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Study approval

All animal experiments were conducted under an animal protocol approved by the IACUC of Rutgers University.

Author contributions

ML performed most experiments directed by SFB, who wrote the manuscript. FC did analysis of meiosis and assisted with the manuscript. DSP did RAD51 IF. SMM prepared the samples for MS and SCE analysis. JH performed additional IF experiments. AM maintained mouse cohorts and prepared the samples for the tumorigenesis study. AA performed RT–PCR analysis of Brca1 expression. HZ conducted MS experiments. RB, TL, MJ, and AN assisted with writing of the manuscript. LS designed and conducted the DNA combing experiments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Peter Lobel for advice on MS and Jake Altshuler for assistance with data analysis. This work was supported by NCI R00CA160574. DP and SM were supported by the Rutgers Biotech Training Program (T32 GM008339) and by predoctoral awards from the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research. FC was supported by NIH grant DP2HD087943. The Rutgers Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility was supported by NIH S10OD016400.

EMBO Reports (2016) 17: 1532–1541

References

- 1. Brodie SG, Deng CX (2001) BRCA1‐associated tumorigenesis: what have we learned from knockout mice? Trends Genet 17: S18–S22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roy R, Chun J, Powell SN (2012) BRCA1 and BRCA2: different roles in a common pathway of genome protection. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 68–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M (1999) Brca1 controls homology‐directed DNA repair. Mol Cell 4: 511–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hashizume R, Fukuda M, Maeda I, Nishikawa H, Oyake D, Yabuki Y, Ogata H, Ohta T (2001) The RING heterodimer BRCA1‐BARD1 is a ubiquitin ligase inactivated by a breast cancer‐derived mutation. J Biol Chem 276: 14537–14540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalb R, Mallery DL, Larkin C, Huang JT, Hiom K (2014) BRCA1 is a histone‐H2A‐specific ubiquitin ligase. Cell Rep 8: 999–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu LC, Wang ZW, Tsan JT, Spillman MA, Phung A, Xu XL, Yang MC, Hwang LY, Bowcock AM, Baer R (1996) Identification of a RING protein that can interact in vivo with the BRCA1 gene product. Nat Genet 14: 430–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu Q, Pao GM, Huynh AM, Suh H, Tonnu N, Nederlof PM, Gage FH, Verma IM (2011) BRCA1 tumour suppression occurs via heterochromatin‐mediated silencing. Nature 477: 179–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reid LJ, Shakya R, Modi AP, Lokshin M, Cheng JT, Jasin M, Baer R, Ludwig T (2008) E3 ligase activity of BRCA1 is not essential for mammalian cell viability or homology‐directed repair of double‐strand DNA breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20876–20881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shakya R, Reid LJ, Reczek CR, Cole F, Egli D, Lin CS, deRooij DG, Hirsch S, Ravi K, Hicks JB et al (2011) BRCA1 tumor suppression depends on BRCT phosphoprotein binding, but not its E3 ligase activity. Science 334: 525–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cao L, Xu X, Bunting SF, Liu J, Wang RH, Cao LL, Wu JJ, Peng TN, Chen J, Nussenzweig A et al (2009) A selective requirement for 53BP1 in the biological response to genomic instability induced by Brca1 deficiency. Mol Cell 35: 534–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bouwman P, Aly A, Escandell JM, Pieterse M, Bartkova J, van der Gulden H, Hiddingh S, Thanasoula M, Kulkarni A, Yang Q et al (2010) 53BP1 loss rescues BRCA1 deficiency and is associated with triple‐negative and BRCA‐mutated breast cancers. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 688–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bunting SF, Callen E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez‐Capetillo O, Cao L et al (2010) 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in Brca1‐deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 141: 243–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ludwig T, Chapman DL, Papaioannou VE, Efstratiadis A (1997) Targeted mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene homologs in mice: lethal phenotypes of Brca1, Brca2, Brca1/Brca2, Brca1/p53, and Brca2/p53 nullizygous embryos. Genes Dev 11: 1226–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shakya R, Szabolcs M, McCarthy E, Ospina E, Basso K, Nandula S, Murty V, Baer R, Ludwig T (2008) The basal‐like mammary carcinomas induced by Brca1 or Bard1 inactivation implicate the BRCA1/BARD1 heterodimer in tumor suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7040–7045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evers B, Jonkers J (2006) Mouse models of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency: past lessons, current understanding and future prospects. Oncogene 25: 5885–5897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bunting SF, Callen E, Kozak ML, Kim JM, Wong N, Lopez‐Contreras AJ, Ludwig T, Baer R, Faryabi RB, Malhowski A et al (2012) BRCA1 functions independently of homologous recombination in DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mol Cell 46: 125–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brzovic PS, Keeffe JR, Nishikawa H, Miyamoto K, Fox D 3rd, Fukuda M, Ohta T, Klevit R (2003) Binding and recognition in the assembly of an active BRCA1/BARD1 ubiquitin‐ligase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 5646–5651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Joukov V, Chen J, Fox EA, Green JB, Livingston DM (2001) Functional communication between endogenous BRCA1 and its partner, BARD1, during Xenopus laevis development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12078–12083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lu Y, Amleh A, Sun J, Jin X, McCullough SD, Baer R, Ren D, Li R, Hu Y (2007) Ubiquitination and proteasome‐mediated degradation of BRCA1 and BARD1 during steroidogenesis in human ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 21: 651–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prakash R, Zhang Y, Feng W, Jasin M (2015) Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a016600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sy SM, Huen MS, Chen J (2009) PALB2 is an integral component of the BRCA complex required for homologous recombination repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7155–7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schlacher K, Wu H, Jasin M (2012) A distinct replication fork protection pathway connects Fanconi anemia tumor suppressors to RAD51‐BRCA1/2. Cancer Cell 22: 106–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ray Chaudhuri A, Callen E, Ding X, Gogola E, Duarte AA, Lee JE, Wong N, Lafarga V, Calvo JA, Panzarino NJ et al (2016) Replication fork stability confers chemoresistance in BRCA‐deficient cells. Nature 535: 382–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xu X, Qiao W, Linke SP, Cao L, Li WM, Furth PA, Harris CC, Deng CX (2001) Genetic interactions between tumor suppressors Brca1 and p53 in apoptosis, cell cycle and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet 28: 266–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ward IM, Minn K, van Deursen J, Chen J (2003) p53 Binding protein 53BP1 is required for DNA damage responses and tumor suppression in mice. Mol Cell Biol 23: 2556–2563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meistrich ML, Hess RA (2013) Assessment of spermatogenesis through staging of seminiferous tubules. Methods Mol Biol 927: 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Turner JM (2015) Meiotic Silencing in Mammals. Annu Rev Genet 49: 395–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Turner JM, Aprelikova O, Xu X, Wang R, Kim S, Chandramouli GV, Barrett JC, Burgoyne PS, Deng CX (2004) BRCA1, histone H2AX phosphorylation, and male meiotic sex chromosome inactivation. Curr Biol 14: 2135–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu X, Weaver Z, Linke SP, Li C, Gotay J, Wang XW, Harris CC, Ried T, Deng CX (1999) Centrosome amplification and a defective G2‐M cell cycle checkpoint induce genetic instability in BRCA1 exon 11 isoform‐deficient cells. Mol Cell 3: 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fernandez‐Capetillo O, Chen HT, Celeste A, Ward I, Romanienko PJ, Morales JC, Naka K, Xia Z, Camerini‐Otero RD, Motoyama N et al (2002) DNA damage‐induced G2‐M checkpoint activation by histone H2AX and 53BP1. Nat Cell Biol 4: 993–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Drost R, Bouwman P, Rottenberg S, Boon U, Schut E, Klarenbeek S, Klijn C, van der Heijden I, van der Gulden H, Wientjens E et al (2011) BRCA1 RING function is essential for tumor suppression but dispensable for therapy resistance. Cancer Cell 20: 797–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drost R, Dhillon KK, van der Gulden H, van der Heijden I, Brandsma I, Cruz C, Chondronasiou D, Castroviejo‐Bermejo M, Boon U, Schut E et al (2016) BRCA1185delAG tumors may acquire therapy resistance through expression of RING‐less BRCA1. J Clin Investig 126: 2903–2918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Y, Krais JJ, Bernhardy AJ, Nicolas E, Cai KQ, Harrell MI, Kim HH, George E, Swisher EM, Simpkins F et al (2016) RING domain‐deficient BRCA1 promotes PARP inhibitor and platinum resistance. J Clin Investig 126: 3145–3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ward IM, Reina‐San‐Martin B, Olaru A, Minn K, Tamada K, Lau JS, Cascalho M, Chen L, Nussenzweig A, Livak F et al (2004) 53BP1 is required for class switch recombination. J Cell Biol 165: 459–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K (1997) B lymphocyte‐specific, Cre‐mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 1317–1318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barlow JH, Faryabi RB, Callen E, Wong N, Malhowski A, Chen HT, Gutierrez‐Cruz G, Sun HW, McKinnon P, Wright G et al (2013) Identification of early replicating fragile sites that contribute to genome instability. Cell 152: 620–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Craig R, Cortens JP, Beavis RC (2004) Open source system for analyzing, validating, and storing protein identification data. J Proteome Res 3: 1234–1242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cole F, Kauppi L, Lange J, Roig I, Wang R, Keeney S, Jasin M (2012) Homeostatic control of recombination is implemented progressively in mouse meiosis. Nat Cell Biol 14: 424–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Misenko SM, Bunting SF (2014) Rapid analysis of chromosome aberrations in mouse B lymphocytes by PNA‐FISH. J Vis Exp 90: e51806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vazquez BN, Thackray JK, Simonet NG, Kane‐Goldsmith N, Martinez‐Redondo P, Nguyen T, Bunting S, Vaquero A, Tischfield JA, Serrano L (2016) SIRT7 promotes genome integrity and modulates non‐homologous end joining DNA repair. EMBO J 35: 1488–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Expanded View Figures PDF

Review Process File