Abstract

Historically, cancers have been treated with chemotherapeutics aimed to have profound effects on tumor cells with only limited effects on normal tissue. This approach was followed by the development of small‐molecule inhibitors that can target oncogenic pathways critical for the survival of tumor cells. The clinical targeting of these so‐called oncogene addictions, however, is in many instances hampered by the outgrowth of resistant clones. More recently, the proper functioning of non‐mutated genes has been shown to enhance the survival of many cancers, a phenomenon called non‐oncogene addiction. In the current review, we will focus on the distinct non‐oncogenic addictions found in cancer cells, including synthetic lethal interactions, the underlying stress phenotypes, and arising therapeutic opportunities.

Keywords: cancer, non‐oncogene addiction, synthetic lethality, therapy, vulnerability

Subject Categories: Cancer, Stem Cells

Glossary

- ABL

ABL proto‐oncogene 1, non‐receptor tyrosine kinase

- ALK

Anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase

- ALL

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- APC/C

Anaphase‐promoting complex/cyclosome

- ATM

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATP

Adenosine 5'‐triphosphate

- ATR

Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3‐related

- AURKA

Aurora kinase A

- AURKB

Aurora kinase B

- BCR

BCR, RhoGEF, and GTPase‐activating protein

- BRAF

B‐Raf proto‐oncogene, serine/threonine kinase

- BRCA1

Breast cancer 1

- BRCA2

Breast cancer 2

- BUD31

BUD31 homolog

- CDC6

Cell division cycle 6

- CDK1

Cyclin‐dependent kinase 1

- CDK2

Cyclin‐dependent kinase 2

- CDK

Cyclin‐dependent kinase

- CHK1

Checkpoint kinase 1

- DDR

DNA damage response

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- DR5

Death receptor 5

- E2F

E2F transcription factor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- EIF4EBP1

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1

- EIF4E

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E

- FBXW7

F‐box and WD repeat domain‐containing 7

- GATA2

GATA binding protein 2

- GSK3B

Glycogen synthase kinase 3B

- GST

Glutathione S‐transferase

- HER2

Erb‐b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- HIF1

Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1

- HRAS

Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- HR

Homologous recombination

- HSET

Kinesin‐related protein HSET

- HSF1

Heat‐shock factor 1

- HSP70

Heat‐shock protein 70

- HSP90

Heat‐shock protein 90

- KIF2C

Kinesin family member 2C

- KIFC1

Kinesin family member C1

- KIT

KIT proto‐oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase

- KRAS

Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- MAPK

Mitogen‐activated protein kinase

- MED4

Mediator complex subunit 4

- MPS1

Monopolar spindle 1

- MTH1

MutT‐type nudix hydrolase 1

- mTOR

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- MYCL

v‐myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene lung carcinoma‐derived homolog

- MYCN

v‐myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma‐derived homolog

- MYC

v‐myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog

- NBS1

Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1

- NFE2L2

Nuclear factor, erythroid 2‐like 2

- NFκB

Nuclear factor kappa B

- NHEJ

Non‐homologous end joining

- NLK

Nemo‐like kinase

- NRAS

Neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog

- NRF2

Nf‐E2‐related factor 2

- NUDT1

Nudix hydrolase 1

- PARP

Poly‐(ADP‐ribose) polymerase

- PDK1

Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol‐3‐kinase

- PIP4K2

Phosphatidylinositol‐5‐phosphate 4‐kinase type 2

- PLK1

Polo‐like kinase 1

- PLK4

Polo‐like kinase 4

- PNKP

Polynucleotide kinase 3'‐phosphatase

- PRKDC

Protein kinase DNA‐activated catalytic polypeptide

- PTEN

Phosphatase and tensin homolog

- RAD51

RAD51 recombinase

- RAS

Rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog

- RB1

Retinoblastoma 1

- RHEB

RAS homolog enriched in brain

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SAE1

SUMO‐activating enzyme 1

- SAE2

SUMO‐activating enzyme 2

- siRNA

Short interfering RNA

- SKP2

S‐phase kinase‐associated protein 2

- SNAI2

Snail family zinc finger 2

- SODs

Superoxide dismutases

- TP53

Tumor protein p53

- TRAIL

TNF‐related apoptosis inducing ligand

- TSC2

Tuberous sclerosis 2

- WNT

Wingless type

- WT1

Wilms tumor 1

Introduction

With around 15 million new cases per year, and 8 million deaths related to this disease, cancer is one of the leading causes of death worldwide 1. Most commonly, tumors that cannot be eradicated by surgery or radiotherapy due to metastatic dissemination or the risk thereof are combatted using therapeutics interfering with one of the hallmarks of cancer that distinguishes them from normal tissues 2. For example, tumor cells generally are more sensitive to DNA‐damaging agents and compounds interfering with mitotic progression compared to their non‐transformed counterparts, mostly due to their increased proliferation rates 3, 4. Even decades after their introduction into the clinic, many of these compounds are still the standard of care for many tumor types. Some cancers, such as testicular germ cell tumors, show remarkable remissions or even complete eradication after the administration of DNA‐damaging agents, proving that these therapies can be highly effective 5. In contrast to this, rapid development of resistance to genotoxic compounds is observed in many other tumor types, such as small‐cell lung cancer, ovarian cancer, and head‐and‐neck cancer 6, 7, 8. In addition, the administration of these drugs is accompanied by severe side effects, mostly related to damage inflicted on proliferative normal tissues, such as hematopoietic precursors and gastrointestinal mucosal cells 9. These limitations of currently used chemotherapeutics underscore the need for novel cancer cell‐specific drug combinations that provide high efficacy with limited side effects.

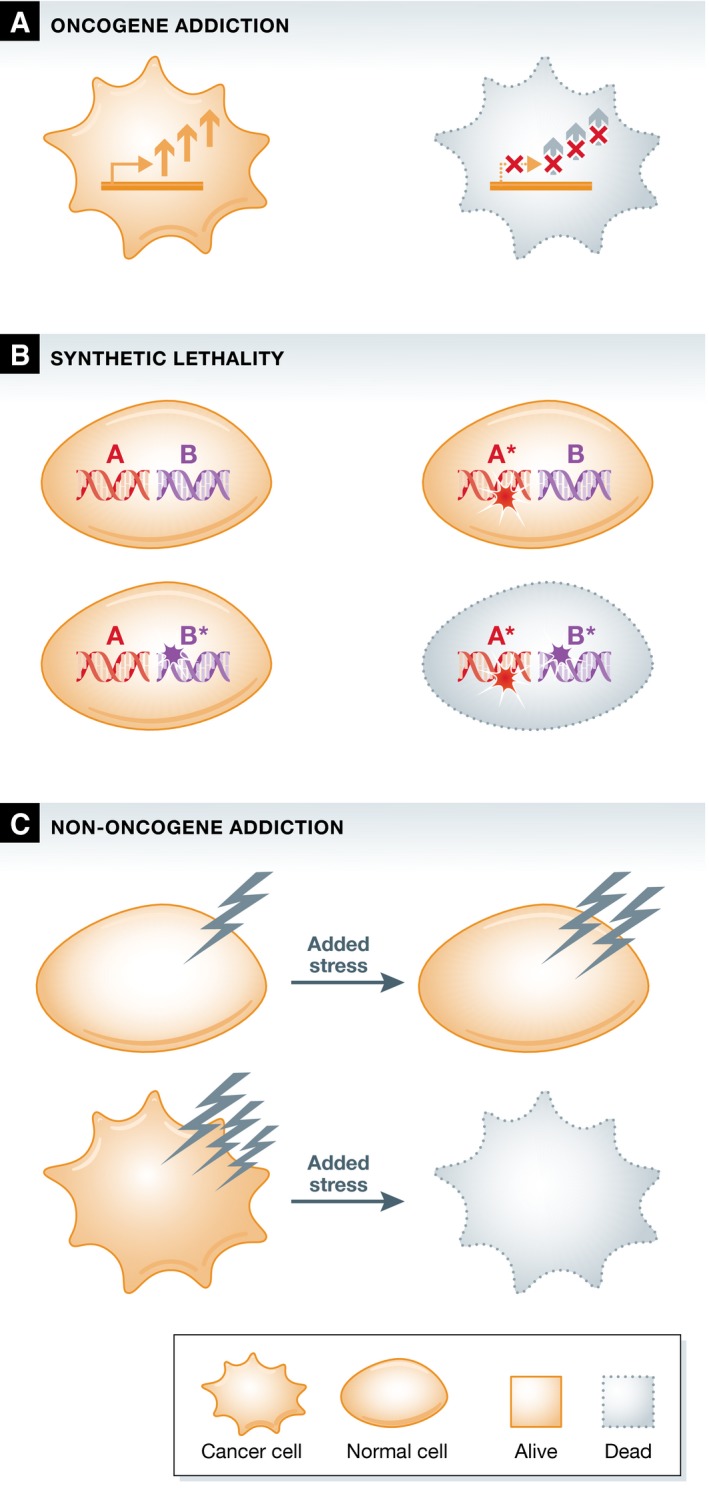

Several tumor cell types critically depend on the continuous activation of oncogenic signaling for their survival, a phenomenon termed “oncogene addiction” (Fig 1A) 10. This finding has led to the development of several therapies designed to inhibit the activated oncogene, which was hypothesized to eradicate tumor cells containing enhanced oncogenic signaling while sparing the normal tissue. The introduction of Herceptin (trastuzumab), an antibody that inhibits the HER2 oncogene in breast cancer, showed that this strategy was extremely effective against HER2‐dependent cancers 11. This success was soon followed by the development of inhibitors targeting several other oncogenes, such as the BCR‐ABL fusion gene in chronic myeloid leukemia 12, KIT in gastrointestinal tumors 13, EGFR and ALK in non‐small‐cell lung cancer 14, 15, and BRAF in melanoma 16. Unfortunately, even though in many instances remissions were observed, this was frequently followed by the reappearance of drug‐resistant tumor clones.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of cellular effects of oncogene addiction, synthetic lethality, and non‐oncogene addiction.

(A) Oncogene addiction. Cancer cells need continuous oncogenic signaling for their survival. Increased oncogenic signaling in the cancer cell is schematically represented by the arrows. (B) Synthetic lethality. The mutation of individual genes is compatible with cell viability, whereas the combined mutation of these genes leads to cell death. (C) Non‐oncogene addiction. Cancer cells harbor elevated levels of various stresses, caused by collateral events during the tumorigenic process. Tumor cells can be specifically killed by application of additional stress, or by inhibition of specific salvage pathways, whereas normal cells can tolerate these perturbations.

In addition to the complications caused by drug resistance, the strategy of targeting oncogene addiction can only be applied to a limited number of cases. This stems from the fact that most mutations found in tumors, including some oncogene activating mutations and all loss‐of‐function mutations, are not directly druggable. The abundantly activated oncogenes RAS and MYC, for example, have been shown to be essential for tumor cell survival in in vitro and in vivo models harboring active forms of these genes and are prime examples of oncogene addiction 17, 18. Unfortunately, it appears difficult to identify compounds that are able to efficiently inhibit these specific oncogenes. Similarly, no compounds are available that can restore the loss of function of tumor suppressor genes. To overcome this problem, it was proposed that anticancer treatment should be focused not only on directly counteracting the oncogenic mutations, but also on the altered dependencies of cancer cells on non‐mutated genes 19. This proposal is based on the genetic studies in Drosophila that showed genetic incompatibility between mutations referred to as synthetic lethality. Synthetic lethality describes the phenomenon of a lethal combination of perturbations in two genes, where mutation in either of those genes alone does not affect cell viability (Fig 1B) 20. Reasoning along those lines, it was therefore proposed that targeting a synthetic lethal partner of a mutated driver gene in tumor cells may allow for therapeutic intervention that would spare normal cells 19.

In the search for synthetic lethal interactors that could be exploited for cancer therapy, it was also observed that tumor cells often display increased levels of various stresses. The tumorigenic process induces re‐wiring of many processes and leads to augmented cellular stress levels, such as increases in DNA damage and replication stress, metabolic stress, and proteotoxic and oxidative stress 21, 22. These stress phenotypes have been observed in many distinct tumor types, and even though it is not completely understood how some of them originate, their induction appears to be tightly linked to oncogenesis. Different tumors have been shown to critically depend on the reduction of these stress levels for their survival. To exploit this cancer‐specific stress phenotype, two approaches have been proposed that would affect tumor cells while sparing normal cells. On the one hand, inhibition of stress‐reducing pathways would be expected to increase the levels of stress specifically in tumor cells to critical levels. On the other hand, applying a stress overload can specifically kill cancer cells as they possess less buffering capacity in comparison with normal cells 21. Therefore, re‐sensitizing tumor cells to their increased stress levels or generating imbalances in these levels by application of additional stress has been put forward as a promising means for therapeutic intervention 23.

The survival of cancer cells thus depends on a multitude of factors that distinguish them from non‐transformed cells, which include but are not limited to oncogenic drivers. In contrast to normal cells, tumor cells might rely on the constitutive function of genes that are synthetic lethal partners of driver mutations. In addition, they also rely on pathways that are able to buffer the increased stress levels that are encountered. As these genes and pathways are generally not contributing to oncogenesis itself, the dependency on their proper function has collectively been dubbed “non‐oncogene addiction” (Fig 1C) 23. As most synthetic lethal partners of oncogenic driver genes are not contributing to tumorigenesis, but are essential for tumor cell survival, synthetic lethality can be regarded as a specific subtype of non‐oncogene addiction. In the following section, currently known non‐oncogene addictions and the stress phenotypes they relate to will be described. Next, the specific synthetic lethal partners of driver genes frequently mutated in cancer will be discussed, with a specific emphasis on the stress phenotypes they are affecting.

Non‐oncogene addiction

Proteotoxic stress

Many of the dependencies on stress relief have been identified by forward genetic screens in cell lines harboring mutations frequently found in human cancers. Several of these genomewide screens aiming to identify genes essential for cancer cell survival yielded multiple hits in genes involved in proteasomal degradation and protein folding 24, 25, 26. Even though components of these processes have generally been regarded to be essential for any cell, a wealth of accumulated data suggest a higher dependency of cancer cells on these genes for their survival.

In vivo knockdown of HSF1, the master regulator of the heat‐shock response that protects cells from protein misfolding and aggregation showed this protein to be essential for tumor initiation and maintenance. HSF1 is induced by various protein‐denaturing stresses and, among others, regulates the expression of the chaperones HSP70 and HSP90 27, 28. Somatic mutations in HSF1 have not been recorded in human tumors and increases in HSF1 gene expression are unable to transform cells, suggesting that the protein itself is not causative for tumorigenesis. In contrast, chemically and genetically induced tumor formation was greatly affected in Hsf1 knockout mice, leading to reduced tumor incidence and tumor volumes in the absence of HSF1 29. Strikingly, Hsf1 is dispensable for growth and survival in the absence of acute stress, which indicates that the dependency of cancer cells on Hsf1 is a vital non‐oncogene addiction 29, 30.

Tightly linked to the dependency of cancer cells on increased protein folding capacity is their dependency on proteasomal degradation. It has been shown that genetic aberrations can lead to an elevated level of proteotoxic stress. Aneuploidy, copy number variations, and transcriptional alterations affect the dosage of components of protein complexes and thereby promote the formation of protein aggregates 31, 32, 33. Furthermore, specific gene mutations leading to improperly folded proteins are an additional source of increased proteotoxic stress 34. This elevated stress level presumably needs to be reduced via an upregulation of proteasomal degradation and protein folding capacity to allow for survival. Indeed, upregulation of HSF1, HSP70, and HSP90 and increases in proteasomal degradation are common events in human cancers 27, 35. In addition, upregulation of autophagy has been shown to be another means for tumor cells to reduce proteotoxic stress as it poses an alternative route to clear damaged or aggregated proteins. Augmented autophagy is observed in many cancers, suggesting that tumor cells highly depend on this process to alleviate the proteotoxic stress they encounter 36, 37. Interestingly, inhibition of these antistress responses shows promising anticancer activity, demonstrating the efficacy of exacerbation of the proteotoxic stress encountered by tumor cells 22, 38.

For currently unknown reasons, KRAS mutant tumors are more sensitive to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib 39. Additionally, cancers bearing specific BRAF or EGFR mutations have an increased sensitivity toward HSP90 inhibition, most likely due to these proteins being specific clients of this chaperone 40. Altogether, these findings indicate that targeting of non‐oncogene addiction such as inhibition of the proteasome or heat‐shock response proteins could well serve as precision treatment of cancers.

Oxidative stress

Cancer cells generally suffer from higher levels of oxidative stress than non‐transformed cells 41. The increase in this stress level can be directly caused by oncogenic signaling, which induces elevated levels of ROS 42, 43. Collectively, the higher ROS levels deliver oxidative damage to all macromolecules in the cell, where the most detrimental effects accumulate as mutations in the DNA, leading to genomic instability. The double‐stranded DNA itself, however, is thousands‐fold less susceptible to oxidative damage than the free nucleotides it is composed of 44. Two recent studies showed that cancer cells critically depend on the removal of oxidized nucleotides from the total pool of free nucleotides for their survival. Both studies indicated that the function of the normally non‐essential gene NUDT1 (also known as MTH1) is essential for tumor cell survival 45, 46. Inhibitors of MTH1 selectively killed cancer cells, indicative of their need to reduce the damage inflicted on nucleotides by increased levels of oxidative stress.

In addition to MTH1, also NFE2L2 (better known as NRF2) plays a major role in keeping oxidative stress levels in cancer cells in check. NRF2 is a stress‐induced transcription factor that regulates the expression of many cellular defense enzymes, including antioxidant genes such as the SODs and GST 47, 48. Knockouts for Nrf2 are more prone to develop chemically induced tumors, suggesting that this gene functions as a tumor suppressor and inhibits tumor initiation 49, 50. In various sporadic tumors, however, NRF2 levels are drastically upregulated and high expression of this protein is a marker of poor prognosis 51, 52, 53, 54. These contradictory findings are likely to stem from the antistress function of NRF2. Whereas the presence of NRF2 initially protects against the mutational damage inflicted by ROS and thereby has a negative impact on tumor initiation, in later stages it promotes malignant progression by reducing oxidative stress levels that transformed cells suffer from 55. Thus, whereas NRF2 normally functions as a tumor suppressor, many cancer types eventually become addicted to the expression of this gene in order to survive with their increased ROS levels.

Oxidative stress overload through inhibition of antioxidant proteins could be used to therapeutically target cancer cells, as it reduces the ROS buffering capacity of cells. Similarly, agents that enhance ROS production would be hypothesized to exert the same effect. This approach has already shown promising results in preclinical models, where the ROS‐inducing agent piperlongumine elicited potent antitumor effects. In contrast to the major effects it exerted on cancer cells, the compound only showed limited toxicity toward primary non‐transformed cells 56. In addition, other compounds that induce ROS production, such as dichloroacetate and beta‐phenylethyl isothiocyanate, have shown similar anticancer effects 57, 58. Collectively, these studies suggest that the generation of an imbalance in oxidative stress levels could be a potent strategy to combat cancer.

Metabolic stress

Most normal cells metabolize glucose to carbon dioxide via mitochondrial respiration to generate energy for all cellular processes. In contrast, the large majority of cancers have been shown to switch to an alternative route for their glucose metabolism, glycolysis 59. Coinciding with this change in metabolism, an increased glucose uptake has been observed in the majority of tumors 60. Cancer cells seem to benefit from this switch in metabolism as it results in the formation of intermediate products that can subsequently be used for the generation of fatty acids, nucleotides, and amino acids necessary to support the continuous growth of the tumor 61, 62.

Multiple cellular factors play a role in the upregulation of glycolysis, with hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF1) being one of the main regulators for this switch. In addition to HIF1, oncogenic activation of RAS and the PI3‐kinase pathway or the inactivation of the tumor suppressor TP53 can also induce a switch to glycolysis 63, 64, 65. Mechanistically, enhanced signaling through these pathways results in elevated levels of glucose transporters on the cellular surface thereby causing a glucose‐induced inhibition of mitochondrial respiration and stimulation of glycolysis 66, 67, 68.

Indications that the reliance of tumor cells on an altered glucose metabolism could be used for therapeutic intervention came from studies that inhibited the glycolytic process. When glycolysis was suppressed, tumor cells were unable to sufficiently upregulate mitochondrial respiration, which eventually resulted in cell death 69. Administration of the non‐metabolizable glucose analogues 2‐deoxyglucose or 3‐bromopyruvate inhibited glycolysis and induced apoptosis specifically in cancer cells with compromised mitochondrial respiration 70, 71, 72. Strikingly, 3‐bromopyruvate elicited remarkable reduction in the size of xenografted tumors, without affecting normal tissue 71. Similarly, inhibition of PDK1, an important signaling kinase downstream of HIF1, triggered apoptosis in tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo 73, 74, 75.

In addition to a change in glucose metabolism, changes in amino acid metabolism and the dependency thereon have also been observed in cancer cells. It has, for example, been shown that some rapidly proliferating cancer types have an increased reliance on the production or uptake of the non‐essential amino acids arginine, asparagine, glycine, glutamine, and serine 67, 76, 77, 78, 79. MYC‐driven tumors are particularly sensitive to glutamine withdrawal, because genes involved in glutamine metabolism are under direct transcriptional control of this oncogene 80, 81, 82. RAS‐driven tumors were shown to depend on macropinocytosis, an endocytic process that leads to internalization of extracellular molecules, for their glutamine supply. The availability of glutamine for these cells can be reduced by pharmacological inhibition of the macropinocytic uptake, which was shown to be effective in targeting RAS‐transformed cells 83. Additionally, specific cancer types are more sensitive to the deprivation of essential amino acids when compared to non‐transformed cells. Whereas normal cells enter a cell cycle arrest upon leucine deprivation, a wide array of melanoma cell lines undergoes apoptosis in the same situation. This differential response was shown to be caused by a failure of melanoma cells to activate autophagy, which would normally be able to liberate molecules, such as leucine, from internal sources 84.

Inhibition of folate and nucleotide metabolism with agents such as methotrexate and pemetrexed already resulted in clinical benefit 85. This suggests that depletion of essential metabolic end products can specifically target tumor cells and would be a means for therapeutic intervention. The direct deprivation of nutrients from the tumor microenvironment to induce tumor cell death in vivo has proven to be difficult. Nonetheless, the administration of L‐asparaginase, a bacterial enzyme that deaminates and thereby destabilizes asparagine, has significantly improved the outcomes for ALL 86. ALL cells are particularly sensitive to limited supplies of asparagine as they cannot produce sufficient levels of this molecule to sustain their metabolic demands 87. In addition, the observations that whole‐body metabolic alterations, such as obesity and diabetes, can have profound effects on cancer development have led to studies on the effects of dietary changes on tumor progression 88, 89. Strikingly, when mice bearing TP53‐mutated tumors were fed a diet lacking serine, tumor growth was significantly impaired due to a rapid suppression of glycolysis 77. Similarly, a fasting protocol was able to inhibit tumor growth in vivo, where the delay in progression was comparable to the one seen when classical chemotherapeutics were administered 90. This response was suggested to be a direct result of the incapability of tumor cells to switch to a sufficiently high level of oxidative phosphorylation in environments containing low glucose levels 91. Alternatively, the effects of glucose deprivation could also be mimicked by AMPK activation using metformin, which is able to elicit cell death specifically in TP53‐mutated cells 92. Altogether, these studies indicate that interference with the altered metabolism in cancer is a promising avenue for tumor cell‐specific targeting.

Centrosome clustering

Centrosomes nucleate and organize the microtubule skeleton necessary for equal distribution of sister chromatids to the daughter cells. During each cell cycle, these organelles are duplicated only once, ensuring the proper establishment of a bipolar spindle with both centrosomes serving as poles 93. It has been observed, however, that many tumor cells contain an elevated number of centrosomes, which originate from overduplication or failure of cytokinesis 94, 95. Interestingly, loss of the tumor suppressors TP53, RB1, BRCA1, or BRCA2 or the expression of the human papillomavirus oncoproteins E6 or E7 can all lead to centrosome amplification, suggesting a causal role for some tumorigenic events in this overduplication 96, 97, 98, 99, 100.

An amplified number of centrosomes generally induce multipolar cell division, which is detrimental to cell survival as it leads to mitotic catastrophe 101. Strikingly, this multipolarity can be prevented by centrosomal clustering at the poles, which generates a pseudo‐bipolar spindle that allows for normal division 102, 103. The molecular mechanism behind this clustering has not yet been fully elucidated, but proteins that involved the spindle assembly checkpoint, acto‐myosin contractility, kinetochore and microtubule attachment, the chromosome passenger complex, sister chromatid cohesion components, and microtubule‐associated proteins have all been shown to play a role in this process 104, 105. As cells with supernumerary centrosomes rely on their clustering for proper cell division, inhibition of these proteins has been proposed as a means to specifically target cancer cells. Indeed, inhibition of the microtubule‐associated motor protein KIFC1 (better known as HSET) leads to the declustering of centrosomes and elicits death specifically in cells with amplified centrosomes 104, 106. Along these lines, several compounds have been identified that induce centrosome declustering leading to cancer cell death, while leaving non‐transformed cells unaffected 107, 108, 109, 110. Centrosome declustering to disrupt the mitotic balance in cancer cells thus emerges as a promising anticancer strategy, which currently awaits further clinical validation.

DNA damage stress/replication stress

It has been long recognized that impaired DNA damage repair can lead to tumorigenesis as it can result in an accumulation of mutations, amplifications, deletions, and chromosomal rearrangements. This increase in genomic instability is considered to be a driving force for transformation, as elevated levels of DNA damage are already observed in the earliest stages of the development of various cancers 111. Accidental lesions occurring in proto‐oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes may trigger this. In line with this, many tumor suppressors function in different DDR pathways and their loss severely compromises the capacity to repair damaged DNA, which can even lead to a severe predisposition to the development of cancer in the case of inherited genetic mutations in DDR genes. These predisposing mutations have been identified in well‐known tumor suppressors, such as ATM, NBS1, BRCA1, and BRCA2, and the Fanconi anemia genes 112. In addition to loss of tumor suppressors leading to elevated DNA damage levels, the activation of many oncogenes can also enhance the level of genomic instability by the induction of replication stress. In particular, elevated levels of MYC can induce replication stress through induction of hyper‐replication and unscheduled firing of extra origins of replication 113. This can ultimately result in the collapse of replication forks and generate double‐stranded DNA breaks.

For decades, the interference with DNA damage stress levels has been used as a strategy to combat cancer, and it is still the mainstay for treatment of many tumor types. Ionizing radiation and DNA‐damaging agents take advantage of the high genomic instability of cancer cells by overloading their stress defense system. The development of several targeted therapies that inhibit proteins involved in DDR pathways has brought novel opportunities to generate imbalances in the DNA damage stress load in cancer cells. Interference with the function of the main sensor kinase for replicative stress, ATR, seems to be an especially powerful method to specifically target MYC‐induced cancers. For example, MYC‐driven tumorigenesis could be prevented by genetic ablation of ATR in both lymphoma and pancreatic mouse models 114, 115. In addition, MYC overexpression seems to induce sensitivity to inhibitors of ATR and CHEK1, the downstream relaying kinase of ATR 114, 116. These preclinical studies suggest that destabilization of replication forks by inhibition of the ATR signaling axis could prove to be valuable in the targeting of cancer cells that harbor oncogene‐induced replicative stress.

Synthetic lethality

BRCA–PARP

The presence of a multitude of DNA damage repair pathways, such as HR, NHEJ, and base excision repair, ensures that non‐transformed cells can cope with the genomic insults they encounter. Interestingly, when tumor cells lose functionality of one specific repair pathway, they seem to become highly dependent on the remaining repair pathways for their survival 117. This observation has led to the development of specific therapies that exploit a synthetic lethal vulnerability in two individual DDR pathways. The paradigm synthetic lethal interaction between the HR and NHEJ is currently being used to treat BRCA‐deficient breast and ovarian cancers 118. The loss of BRCA1 or BRCA2 function leads to impaired HR, creating a critical dependency on NHEJ for the repair of double‐stranded breaks in the DNA. PARP inhibitors are able to abrogate the NHEJ pathway, and administration of these inhibitors results in the accumulation of unrepaired DNA and eventually elicits cell death specifically in BRCA‐deficient tumors 119. Similar to this, any tumor deficient in HR would be expected to be vulnerable to PARP inhibition, which is why current investments are being made to identify more markers for HR deficiency.

PTEN

The PTEN gene is one of the most frequently inactivated tumor suppressors in human cancer 120. It has been long recognized that one of the main functions of PTEN is to dephosphorylate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5‐trisphosphate leading to the formation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5‐bisphosphate. Hereby PTEN antagonizes the activity of the highly oncogenic PI3K pathway, which promotes cell survival, proliferation, growth, and cellular metabolism 121. More recently, a novel function of PTEN was observed in studies on the genomic instability that is displayed by Pten knockout mice. As it was previously thought that PTEN's function was being executed in the cytoplasm, it came as quite a surprise that these novel studies showed an additional role for PTEN in the nucleus. PTEN was shown to directly act on the chromatin, and deletion of the gene reduced the transcription levels of Rad51, an essential recombinase involved in HR 122. The reduction of Rad51 levels in PTEN‐deficient cells leads to a fivefold decrease in the capacity to repair DNA double‐strand breaks via HR, thereby decreasing genomic stability 123.

Considering the different functions of PTEN, the specific targeting of PTEN‐deficient cells has been approached via two routes. On the one hand, inhibition of mTOR, a direct downstream target in the PI3K pathway, is preferentially toxic to PTEN‐deficient cells, underscoring the oncogenic addiction of PTEN‐mutated cells to the PI3K pathway 124, 125. On the other hand, synthetic lethal partners of PTEN have been identified which have an impact on the elevated levels of DNA damage that result from the loss of this protein. Similar to BRCA‐deficient cells, PTEN‐deleted cells exhibited a decreased capacity for HR, and are thereby extremely sensitive to the inhibition of PARP 123, 126, 127. Strikingly, rescue experiments making use of mutant forms of PTEN showed that the phosphatase‐inactive forms of this protein were still able to give resistance to PARP inhibitors. In addition, impairment of the nuclear localization of functional PTEN leads to sensitivity to PARP inhibition, indicating that the sole determinant of sensitivity to these inhibitors is the nuclear function of PTEN 123. Analogous to their dependency on PARP, PTEN‐deficient cells are also relying on the function of PNKP for their survival 128. PNKP participates in multiple DNA repair pathways, and the dependency of PTEN‐deficient cells on this protein therefore reinforces the finding that these cells highly depend on DNA repair pathways other than HR for their survival 129.

Tightly linked to the dependency on DNA repair, PTEN‐null cells are also highly sensitive to inhibition of checkpoint kinases. Specifically, these synthetic lethal interactions were identified with a variety of mitotic spindle kinases, which normally respond to aberrant mitoses upon DNA damage. The synthetic lethal partners for PTEN in this group of kinases include NLK, PLK4, and MPS1 130, 131. Inhibition of these kinases in PTEN‐deficient cells specifically led to aberrant division and mitotic catastrophe, suggesting that these cells rely on this checkpoint due to their increased level of DNA damage stress 131. More recently, ATM was brought forward as a synthetic lethal partner for PTEN. Inhibition of ATM in PTEN‐null cells led to many mitotic abnormalities 132, suggesting that both ATM and the mitotic checkpoint kinases are essential to prevent mitotic catastrophe in these cells.

In summary, all these studies suggest that the loss of PTEN leads to an oncogenic addiction to the PI3K pathway, as well as to salvage pathways that deal with the increased DNA damage stress induced by the loss of this gene. Many of the described synthetic lethal interactions can be exploited therapeutically, as a wide range of inhibitors are available for all these kinases and DNA damage repair proteins.

TP53

Aberrations in TP53 are found in about 50% of all tumors making it the most frequently mutated gene in cancer 133. The wild‐type p53 protein is stabilized upon DNA damage, after which it exerts its protective function to allow for repair of the damaged DNA 134. Due to the cytoprotective function, this gene is considered as one of the guardians of the genome, and hence, its loss allows for the accumulation of other mutations needed during the carcinogenic process 135. TP53 performs its functions via multiple mechanisms, including the establishment of a cell cycle arrest in G1/S‐phase, activation of DNA repair pathways, and induction of apoptosis 133.

As cells that lack functional p53 are unable to instigate a DNA damage‐induced G1 arrest, they seem to heavily rely on a functional G2/M cell cycle checkpoint for their survival. This is illustrated by the identification of synthetic lethal interactions of TP53 with a variety of mitotic kinases, including CDK1, PLK1, AURKA, and WEE1. Inhibition of these kinases exerted potent cytotoxic effects specifically on p53‐deficient tumor cells 136, 137, 138, 139. These studies thus suggest that at least one functional DNA damage‐induced cell cycle checkpoint has to be maintained for cancer cells to survive, thereby making the unaffected checkpoint in cancer cells a prime target for therapeutic intervention.

In addition to the necessity for a functional G2/M cell cycle checkpoint in TP53 mutant cells, the proper resolution of replication stress seems to be of utmost importance for the survival of these cells. Both ATR and its downstream kinase CHEK1 have been shown to allow p53‐null cells to survive 140, 141, 142. Indeed, inhibition of CHEK1 was shown to result in further accumulation of DNA damage in addition to that caused by the lack of TP53 141.

As mentioned earlier, loss of TP53 is able to induce a switch in glucose metabolism from mitochondrial respiration to glycolysis 143, 144, 145. Interestingly, the dependency of TP53‐null cells on glycolysis could be reversed by depletion of PIP4K2. Reduction of the levels of PIP4K2 in TP53‐deficient breast carcinoma lines led to severe growth impairment in vitro, while deletion of PIP4K2 significantly improved overall survival and reduced the tumor burden in TP53 knockout mice 146. These striking effects were likely caused by an increase in the levels of ROS and an impaired glucose metabolism, suggesting that PIP4K2 is needed to sustain the switch in glucose metabolism observed in TP53‐null cells 146, 147.

A rather unexpected synthetic lethal interaction was identified between TP53 and POLR2A. This interaction cannot be linked specifically to the function of TP53, but rather originates from a general mode of p53 deletion. Liu and coworkers observed that in a large fraction of colorectal cancers, a deletion of TP53 was invariably accompanied by deletion of essential neighboring genes. They went on to show that inhibition of one such gene, POLR2A, could inhibit proliferation and decrease survival in cells that showed hemizygous loss of TP53 148. This finding encourages research on synthetic lethal partners of TP53 to also focus outside the field of cell cycle and DNA damage processes. However, caution has to be taken with an approach such as the one that was taken in the study of Liu et al, as dose‐dependent side effects are to be expected when this finding is translated to the clinical setting.

RB1

The function of the RB1 tumor suppressor gene is affected by mutations or deletions in a number of specific tumor types. This gene is lost in the large majority of retinoblastomas, small‐cell lung cancers, neuroendocrine prostate cancers, and osteosarcomas. Additionally, it is affected in a subset of pituitary, breast, and bladder cancers 149. The main biological activity of RB1 is its ability to control the cell cycle checkpoint at G1/S transition by binding to E2F family transcription factors and thereby repressing E2F target genes. E2F factors regulate transcription of a multitude of genes involved in cell cycle progression and checkpoint control, nucleotide synthesis, and DNA replication and repair 150. Once RB1 is lost, the inhibitory capacity of this protein is abrogated, leading to an increase in E2F‐mediated transcription and a consequent loss of the G1/S checkpoint.

It is presently impossible to restore the function of RB1 in cancer cells that have lost this gene; therefore, several studies have explored alternative ways to target RB1‐deficient tumors. The functional identity of several synthetic lethal partners of RB1 can be explained by the fact that E2F transcription factors can promote both proliferation and apoptosis. As part of a safeguard mechanism, the level of E2F1 is tightly regulated in order to prevent the induction of apoptosis 151, 152. As a direct feedback mechanism resulting from its transcriptional activity, high levels of E2F lead to activation of the cyclin A/CDK2 complex, which in turn can bind and phosphorylate E2F1. This phosphorylation promotes E2F's dissociation from the DNA and inactivates transcription of its target genes, thereby keeping E2F activity in check 153, 154. Blocking the interaction of cyclin A/CDK2 with E2F1 using inhibitory peptides resulted in targeted apoptosis of cells with disrupted RB1 pathway due to the enhanced transcriptional activity of E2F1 155.

Other studies reported the synthetic lethality between RB1 and SKP2, which possibly shows another mechanism that affects the same feedback loop. SKP2 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for targeting the cyclin‐dependent kinase inhibitor p27 for proteasomal degradation 156. SKP2 is in turn targeted for degradation by anaphase‐promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), and pRB serves as an adaptor protein to bring APC/C and SKP2 together 157. This regulatory network was confirmed by a study that showed that re‐expression of pRB in the RB1‐deficient Saos‐2 osteosarcoma cell line resulted in accumulation of p27, which is an early event occurring before RB1‐mediated repression of E2F target genes 158. Interestingly, deletion of both Rb1 and Skp2 resulted in synthetic lethality in the context of pituitary tumor formation in mice 159. Specifically, while Rb1‐deficient mice developed pituitary tumors, no tumor formation was observed when both Rb1 and Skp2 were deleted 159. The authors went on to show that this synthetic lethality is caused via the activity of p27, as a non‐degradable mutant form of p27 mimicked the effect of Skp2 deletion 159. Possibly, the synthetic lethality between SKP2 and RB1 could stem from the feedback mechanism described between cyclin A/CDK2 and E2F. As p27 levels rise upon SKP2 inhibition, it would be able to inhibit cyclin A/CDK2 activity, thereby overactivating E2F 160. Indeed, more recently it was shown that SKP2 is able to limit the activity of E2F1 and thereby suppresses apoptosis in RB1‐deficient cells 161.

Another synthetic lethal interaction with RB1 loss was uncovered following a genetic screen carried out in a Drosophila mutant for the fly homolog of RB1 (rbf). The screen identified the fly homolog of TSC2 (gig) as a synthetic lethal partner of rbf. TSC2 is a GTPase‐activating protein for RHEB, leading to inactivation of this protein and downregulation of mTOR activity 162, 163. mTOR senses and responds to changes in cellular growth conditions, and its activation by growth factors and mitogens leads to increased protein synthesis. In low‐nutrient conditions and cellular stress, TSC2 is activated by phosphorylation and shuts down mTORC1 function through inactivation of RHEB. Conversely, inhibition of TSC2 leads to an increase of protein synthesis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and a decrease in de novo lipid synthesis, which can lead to metabolic, oxidative, and ER stress 164, 165.

Inactivation of both rbf and gig resulted in synergistic induction of cell death in normal developing tissues 166. Furthermore, inhibition of human TSC2 using shRNAs in a human prostate cancer cell line led to cell death of the RB1‐mutant cell line, but not of RB1 wild‐type counterpart. The same held true for other RB1‐mutant cell lines, such as the osteosarcoma SAOS‐2 and breast cancer MDA‐MB‐468 lines 166. The likely mechanism was proposed to be an accumulated increase in ROS levels, particularly in hypoxic conditions, which lead to oxidative stress. In addition, inhibition of both rbf and gig correlated with increased metabolic stress, as well as with defects in G1‐S control, as a consequence of DNA damage 167. These interactions could directly affect processes regulated by RB1 as it has been shown to play an important role in regulation of cell metabolism and stress induction 168, 169, 170. Inhibition of TSC2 could thus be considered as an approach to specifically kill RB1‐mutant cancers, but this is complicated by the fact that inhibition of TSC2 in normal tissues can lead to tumor formation 171. It has been argued, however, that short‐term inactivation of TSC2 may provide a therapeutic window.

In a recent study, a novel synthetic lethal interaction was uncovered between RB1 inactivation and a deregulated WNT pathway. Inactivation of the WNT pathway induced synergistic apoptosis with mutation of RB1 in Drosophila. Interestingly, this was also shown to be a consequence of elevated mTOR activity and excessive metabolic stress 172.

Another synthetic lethal interaction was identified between RB1 and MED4, a subunit of the mediator complex that couples specific transcription factors with the RNA polymerase II transcription machinery 173, 174. RB1 knockout cells could not survive without MED4 both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that MED4 is a survival gene in retinoblastoma. This explained an observation that patients with large RB1 deletions that encompass both RB1 and MED4 develop retinoblastoma only sporadically 174. The function of MED4 is still unknown, and given its ubiquitous expression, it may be that its activity is required for all cell types and is not specific for RB1‐negative cells. Further studies eliminating MED4 in distinct cell types should therefore be performed to understand its role in normal physiology and cancer progression.

MYC

MYC, MYCN, and MYCL constitute the MYC family of transcription factors that are among the most frequently activated oncogenes in human cancers. They regulate a variety of oncogenic functions, increase the rate of DNA synthesis, stimulate transcription and ribosome synthesis, regulate RNA processing, and drive expression of metabolic enzymes 175. As a result, cells that harbor activated MYC genes are characterized by overactive transcription, translation, and metabolism. These characteristics provide cells with faster proliferation rate, the propensity for self‐renewal, and independence from growth signals 175. Furthermore, MYC overexpression has an important role in generating a tumor‐supporting microenvironment 176. On the other hand, this same signaling induces a hypersensitivity to apoptotic stimuli, increased levels of DNA damage and replication stress, and an increased dependency on cell components needed for efficient growth 175. As MYC is currently not effectively druggable, multiple distinct non‐oncogene addictions may provide alternative options to treat MYC‐driven cancers.

Intracellular MYC levels are tightly regulated, and overexpression of MYC sensitizes cells to apoptotic stimuli 177, 178. For example, elevated levels of MYC lead to upregulation of DR5, a receptor for TRAIL 179. It is therefore not surprising that synthetic lethal partners of MYC that impinge on the apoptotic process have been identified. Specifically, inhibition of GSK3B or of FBXW7 potentiated apoptosis of MYC‐expressing cells 180, 181. As GSK3B and FBXW7 work in concert to target MYC for degradation, their inhibition leads to stabilization of MYC protein and sensitizes cells to DR5‐mediated apoptosis. The GSK3B/FBXW7 axis may therefore be functioning as a buffer to keep MYC at a tolerable level, and prevents activation of the DR5/TRAIL pathway 179, 180.

MYC has been shown to induce DNA damage and lead to genomic instability 43, which can result in apoptosis or senescence. To overcome this, tumor cells frequently harbor mutations in components of DNA damage response pathways 182, 183. Due to aberrant sensing and repair of this damage, these cells survive and continue to proliferate in the presence of elevated levels of DNA damage. Even though MYC‐dependent tumors seem to allow for DNA damage to reach extensive levels, their stress buffering capacities can be worn out. Various components of DNA damage repair pathways and regulators of replication stress have been identified as synthetic lethal partners of MYC, including PRKDC 82, 184. Inhibition of PRKDC, a kinase with a critical role in NHEJ‐mediated DNA repair, induced apoptosis as a consequence of further elevated DNA damage levels 184. As discussed earlier, oncogene‐induced replication stress also leads to DNA damage and to a dependency on the main regulators of these stress levels, ATR and CHEK1. Therefore, MYC‐driven tumors can be selectively killed by inhibition of either of these proteins 114, 185, 186.

Several studies have now shown that the increase in DNA damage‐related stress induced by MYC leads to an enhanced dependency on mitotic checkpoint regulation to allow for proper cell division. MYC‐driven tumor cells were shown to depend on the mitotic regulators AURKA, AURKB, and CDK1 for their survival, as inhibition of these proteins resulted in apoptosis and mitotic catastrophe 187, 188, 189, 190, 191. Overall, these studies suggest a critical dependency of MYC‐driven tumors on a properly functioning mitotic checkpoint, even though it cannot be excluded that the Aurora kinases could play a direct role in the stabilization of MYC. Similarly, the SUMO‐activating enzymes SAE1/2 were shown to be critical factors for proper division of MYC‐dependent tumor cells. Inhibition of SAE1 and SAE2 in cells expressing a MYC transgene led to mitotic catastrophe and cell death, suggesting that sumoylation plays a major role in mitotic spindle formation in these cells 192.

As the MYC family members are powerful transcription factors that regulate thousands of genes, their activation could lead to enhanced levels of stress in the mRNA processing machinery. Increased transcription in MYC‐driven cells without concomitant upregulation of spliceosome components may lead to intron retention and a reduction of mRNA stability and levels. Not surprisingly, cell lines derived from MYC‐dependent cancers showed an increased sensitivity to core spliceosome depletion. Specifically, BUD31, a component of the core spliceosome, was found to be a synthetic lethal partner of MYC. This dependency on the spliceosome may be caused by the addiction of these cells to continuous production of specific oncogenic mRNAs. Alternatively, this phenomenon could be explained by a more general non‐oncogene addiction to enhanced levels of mRNA processing machinery induced by MYC‐driven transcription 193. In line with this, MYC‐driven tumor cells seem to be highly vulnerable to inhibition of translation. MYC and mTOR were shown to work in concert to induce phosphorylation of EIF4EBP1. This phosphorylation prevents the binding of EIF4EBP1 to EIF4E, thereby activating EIF4E's capacity to stimulate translation initiation 194. The continuous phosphorylation of EIF4EBP1 by mTOR was shown to be crucial for enhancing translation and pro‐survival signaling in MYC‐driven tumor cells, and inhibition of mTOR showed high efficacy in MYC‐dependent hematological cancers 195, 196. Additionally, in a genomewide loss‐of‐function screen, many genes functioning in the basic transcription machinery and ribosomal RNA synthesis were identified as synthetic lethal partners of MYC, suggesting that MYC‐driven tumors highly depend on the processes of transcription and translation 82.

All the aforementioned studies show that even though it is not currently possible to directly target MYC, there are many alternative routes to selectively target MYC‐driven tumors. The broad availability of inhibitors of mitotic checkpoint kinases and motor proteins suggests that targeting mitotic regulation might be the most easily applied means for therapeutic intervention for these tumors.

RAS

The RAS family of oncogenes, which includes KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS, contains the first oncogenes to be described and are found mutated in about 25–30% of human cancers 197. Normally, RAS genes are activated by growth factor receptors, after which they relay signals downstream via the MAPK pathway. The constitutive activation of RAS oncogenes, most commonly by point mutations, leads to alterations in many processes such as cell cycle progression, growth, migration, cytoskeletal changes, apoptosis, and senescence 197, 198. Due to dependency of a large fraction of tumors on RAS oncogenes for their survival, a variety of drugs have been developed to specifically target these oncogenic proteins. Initial attempts were focused on blocking farnesylation, a common posttranslational modification of RAS, which showed great promise in preclinical studies 197. Unfortunately, subsequent clinical benefit of farnesyl transferase inhibitors could not be shown, which leaves RAS difficult to drug although inhibitors targeting specific RAS mutants are in development 199.

More recently, efforts have been made to understand the non‐oncogene addictions that are induced by RAS signaling. Consistent with the broad cellular involvement of RAS signaling, the identified synthetic lethal partners of RAS genes also function in multiple distinct pathways. Oncogenic signaling generally leads to an induction of replication stress, a phenotype that has been studied in detail in RAS‐mutated cells. Consequently, a number of synthetic lethal partners of RAS play a role in the regulation of replication or in resolving the stresses it delivers. Cyclin A2 and CDC6, both important for the initiation of replication, have been identified as synthetic lethal partners of RAS 39, 200. Even though these genes are directly involved in the replication process, it cannot be excluded that they serve as factors necessary to sustain the continuous cell cycling induced by RAS instead of being involved in buffering the elevated level of replication stress. ATR and CHEK1 are key proteins that respond to replication stress and initiate the repair of damage induced by the activation of RAS, and RAS‐mutated cells are highly sensitive to the inhibition of either of these genes 201, 202.

Likely due to their high proliferative capacity and increased DNA damage, RAS‐mutated cells suffer from elevated levels of mitotic stress and are highly susceptible to interference with the mitotic checkpoint. In several unbiased screens for synthetic lethal partners of RAS, the mitotic regulators APC/C, PLK1, and KIF2C were identified among the strongest hits 39.

Somewhat surprisingly, activation of individual kinases that can directly induce RAS or that relay its signal was shown to exert a synthetic lethal effect in the presence of a mutated RAS gene. In a recent study on 600 lung adenocarcinoma cases, EGFR and RAS mutations were found to be mutually exclusive. The long‐standing dogma implied that because these two genes operate in the same signaling pathway, activation of both would not occur as it poses no selective advantage 203. Unni and coworkers, however, showed that activation of EGFR in mutant RAS‐expressing cells decreased viability, and is highly disadvantageous for tumor cell survival. When tumors were induced in mice by the activation of both of these oncogenes, only tumors that express one of the oncogenes could develop 204. Along the same lines, activation of BRAF in NRAS‐mutated cells led to an induction of the senescent program, even though BRAF is a kinase directly downstream of RAS 205. These results indicate that a fine balance in the level of oncogenic signaling has to be maintained and that oncogenic overdosing can also be detrimental to tumor cells.

RAS‐mutated cells were also reported to depend on several transcription factors for their survival. In particular, the expression of GATA2 and WT1 is crucial for the survival of RAS‐driven cells 200, 206. Not only WT1 itself but also one of its targets, SNAI2, has been reported to be a synthetic lethal partner for RAS 207. It was proposed that RAS‐mutated cells rely on WT1 signaling to induce SNAI2 in order to maintain an EMT phenotype. The dependency of RAS‐mutated cells on GATA2 requires the regulation of the NFκB pathway and the proteasome 208. Components of these highly connected pathways were already identified as synthetic lethal partners of RAS, suggesting that the reduction of proteotoxic stress is of critical importance for cells harboring an activated RAS gene 39, 209.

Knocking down individual interphase CDKs blocked proliferation of NSCLC cell lines with mutant KRAS, while not affecting the growth of cell lines with wild‐type KRAS allele. Ablation of Cdk4 in the presence of a mutant Kras allele in vivo hindered the development of lung tumors. Importantly, loss of Cdk4 prevented development of aggressive lung adenocarcinomas through induction of senescence, which was accompanied by an increased DNA damage response 210. Nanoparticles containing siRNAs targeting CDK4 decreased proliferation of KRAS mutant NSCLC cells but not the KRAS wild‐type cells, while their systemic administration inhibited tumor growth in a xenograft murine model 211.

Concluding remarks

With the results of many genomewide genetic screening efforts, our understanding of pathway interactions and the functional consequences of their signaling has been greatly enhanced. In particular, the identification of many synthetic lethal interactions and non‐oncogene addictions has opened up novel routes for targeting cancer. Many of these findings do, however, still await further clinical validation, which needs to show significant patient benefit. In cases where these synthetic lethal interactions have been explored in patients, the results were often disappointing. Whether this is due to the far more extensive heterogeneity of tumor cells in vivo, including their variable microenvironment and associated signaling, as compared to the highly homogeneous cell culture conditions in which screens are generally performed, remains an open question. It emphasizes the importance for careful in vivo validation in realistic tumor models (Box 1).

Box 1: In need of answers.

-

Are synthetic lethal interactions context‐dependent?

Several genomewide screens have been performed to identify specific synthetic lethal interactors for a unique driver mutation. Screens aiming to identify synthetic lethal partners for the same driver gene, however, have only yielded a limited overlap between studies. This suggests that the cellular context might be a critical determinant for the effectiveness of targeting synthetic lethal partners.

-

How heterogeneous are non‐oncogene addictions?

It has been reported that tumors often possess high degree of heterogeneity, reflected in their genetic makeup, expression patterns, and their interactions with the microenvironment. Therefore, even though cancer cells in general are especially sensitive to stress, individual tumor populations may exhibit differential stress sensitivity and develop distinct non‐oncogenic addictions.

-

Is the therapeutic window large enough to target the non‐oncogene addictions in in vivo settings?

Similar to the treatment with chemotherapeutics, the successful targeting of non‐oncogene addictions depends on the severity of the side effects. Therefore, it is of utmost importance to determine the difference in sensitivity toward stress overload between tumors and normal tissues in in vivo experiments and in clinical trials.

-

Can combination treatments targeting different non‐oncogenic addictions improve outcome?

Reappearance of resistant tumor cells is commonly seen when treatments are performed with classical therapeutics or targeted agents that counteract oncogene addictions. Combining the targeting of multiple non‐oncogenic addictions, or combining these with DNA‐damaging agents, would be expected to overactivate multiple cancer‐specific stress responses and decrease the likelihood of the development of resistant clones.

As appearance of resistant clones is almost invariably observed when oncogene addictions are targeted, the targeting of non‐oncogene addictions by single inhibitors would also be expected to result in the generation of escape mechanisms. This phenomenon is tightly linked to the genetic instability observed in tumor cells, which allows the cells to acquire genetic lesions that confer resistance to drug treatment. It is to be expected, however, that targeting of a combination of different non‐oncogene addictions or combinations of oncogene and non‐oncogene additions would limit the possibilities of escape and thereby provide a clinical benefit. Future work should therefore be dedicated toward the identification of possible resistance mechanisms and the putative combinatorial treatments that include targeting of non‐oncogene addictions.

Overall, the work discussed in this review indicates that in contrast to non‐transformed cells, tumor cells suffer from multiple forms of stress. In general, many of the identified synthetic lethal interactions indicate that cancer cells heavily rely on several pathways that are able to relieve these stresses for their survival. With regard to therapeutic opportunities, this points to the notion that tipping the balance toward an overkill of stress remains a promising avenue to induce tumor cell death. In most instances, the synthetic lethal interactions can be linked to specific antistress defense mechanisms, and therefore can be considered a subclass of non‐oncogene addictions (Table 1). Strikingly, many of the synthetic lethal interactions affect processes that are often targeted by classical chemotherapeutics, namely DNA damage and mitotic stress. Recent work on synthetic lethality suggests that application of more DNA damage or mitotic‐related stress remains a potent approach to kill tumor cells. It also suggests that other stresses, such as proteotoxic and metabolic stress, which are usually elevated in tumor cells, could be exploited for therapeutic intervention. With the advent of more targeted agents that can specifically impinge on these processes, one expects that this should reduce side effects, while generating similar detrimental stress levels specifically in cancer cells.

Table 1.

Overview of the described synthetic lethal partners and the non‐oncogene addictions they are associated with

| Proteotoxic stress | Oxidative stress | Metabolic stress | Mitotic stress | DNA damage/replication stress | Non‐stress‐related | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTEN | mTOR | mTOR | ATM, NLK, PLK4, MPS1 | ATM, PARP, PNKP | ||

| TP53 | PIP4K2 | PIP4K2 | AURKA, CDK1, PLK1, WEE1 | PLK1, WEE1, ATR, CHEK1 | POLR2A | |

| RB1 | SKP2, CCNA, CDK2, TSC2 | TSC2 | TSC2, WNT | |||

| MYC | mTOR, BUD31, EIF4EBP, GSK3B, FBXW7 | mTOR | AURKA, AURKB, CDK1, SAE1, SAE2 | PRKDC, ATR, CHK1 | ||

| RAS | GATA2, TBK1 | APC/C, PLK1, KIF2C | Cyclin A2, CDC6, ATR, CHEK1 | EGFR, BRAF, WT1, SNAI2, CDK4 |

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant of the Dutch Cancer Society and by the ERC Synergy Project CombatCancer granted to A.B.

EMBO Reports (2016) 17: 1516–1531

See the Glossary for abbreviations used in this article.

References

- 1. Fitzmaurice C, Dicker D, Pain A, Hamavid H, Moradi‐Lakeh M, MacIntyre MF, Allen C, Hansen G, Woodbrook R, Wolfe C et al (2015) The Global Burden of Cancer 2013. JAMA Oncol 1: 505–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144: 646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Michels J, Brenner C, Szabadkai G, Harel‐Bellan A, Castedo M, Kroemer G (2014) Systems biology of cisplatin resistance: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 5: e1257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Risinger AL, Mooberry SL (2010) Taccalonolides: novel microtubule stabilizers with clinical potential. Cancer Lett 291: 14–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaelin WG (2005) The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 689–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Semenova EA, Nagel R, Berns A (2015) Origins, genetic landscape, and emerging therapies of small cell lung cancer. Genes Dev 29: 1447–1462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nagel R, Martens‐de Kemp SR, Buijze M, Jacobs G, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH (2013) Treatment response of HPV‐positive and HPV‐negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Oral Oncol 49: 560–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dasari S, Tchounwou PB (2014) Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 740: 364–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrari E, Lucca C, Foiani M (2010) A lethal combination for cancer cells: synthetic lethality screenings for drug discovery. Eur J Cancer 46: 2889–2895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weinstein IB (2002) Cancer. Addiction to oncogenes–the Achilles heal of cancer. Science 297: 63–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slamon DJ, Leyland‐Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M et al (2001) Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 344: 783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hughes TP, Kaeda J, Branford S, Rudzki Z, Hochhaus A, Hensley ML, Gathmann I, Bolton AE, van Hoomissen IC, Goldman JM et al (2003) Frequency of major molecular responses to imatinib or interferon alfa plus cytarabine in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 349: 1423–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, McGreevey LS, Chen C‐J, Van den Abbeele AD, Druker BJ et al (2003) Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol 21: 4342–4349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwak EL, Bang Y‐J, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, Ou S‐HI, Dezube BJ, Jänne PA, Costa DB et al (2010) Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 1693–1703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, Harris PL, Haserlat SM, Supko JG, Haluska FG et al (2004) Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non‐small‐cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med 350: 2129–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, O'Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Grippo JF, Nolop K et al (2010) Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 363: 809–819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Felsher DW, Bishop JM (1999) Reversible tumorigenesis by MYC in hematopoietic lineages. Mol Cell 4: 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, Lenczowski JM, Tichelaar JW, Lizak MJ, Whitsett JA, Koretsky A, Varmus HE (2001) Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K‐Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes Dev 15: 3249–3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, Murray AW, Friend SH (1997) Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science 278: 1064–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lucchesi JC (1968) Synthetic lethality and semi‐lethality among functionally related mutants of Drosophila melanogaster . Genetics 59: 37–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luo J, Solimini NL, Elledge SJ (2009) Principles of cancer therapy: oncogene and non‐oncogene addiction. Cell 136: 823–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Freije JMP, Fraile JM, López‐Otín C (2011) Protease addiction and synthetic lethality in cancer. Front Oncol 1: 25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Solimini NL, Luo J, Elledge SJ (2007) Non‐oncogene addiction and the stress phenotype of cancer cells. Cell 130: 986–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marcotte R, Brown KR, Suarez F, Sayad A, Karamboulas K, Krzyzanowski PM, Sircoulomb F, Medrano M, Fedyshyn Y, Koh JLY et al (2012) Essential gene profiles in breast, pancreatic, and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Discov 2: 172–189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martens‐de Kemp SR, Nagel R, Stigter‐van Walsum M, van der Meulen IH, van Beusechem VW, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH (2013) Functional genetic screens identify genes essential for tumor cell survival in head and neck and lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19: 1994–2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagel R, Stigter‐van Walsum M, Buijze M, van den Berg J, van der Meulen IH, Hodzic J, Piersma SR, Pham TV, Jimenez CR, van Beusechem VW et al (2015) Genome‐wide siRNA screen identifies the radiosensitizing effect of downregulation of MASTL and FOXM1 in NSCLC. Mol Cancer Ther 14: 1434–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jolly C, Morimoto RI (2000) Role of the heat shock response and molecular chaperones in oncogenesis and cell death. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1564–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whitesell L, Lindquist SL (2005) HSP90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dai C, Whitesell L, Rogers AB, Lindquist S (2007) Heat shock factor 1 is a powerful multifaceted modifier of carcinogenesis. Cell 130: 1005–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xiao X, Zuo X, Davis AA, McMillan DR, Curry BB, Richardson JA, Benjamin IJ (1999) HSF1 is required for extra‐embryonic development, postnatal growth and protection during inflammatory responses in mice. EMBO J 18: 5943–5952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Torres EM, Sokolsky T, Tucker CM, Chan LY, Boselli M, Dunham MJ, Amon A (2007) Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science 317: 916–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oromendia AB, Dodgson SE, Amon A (2012) Aneuploidy causes proteotoxic stress in yeast. Genes Dev 26: 2696–2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Santaguida S, Vasile E, White E, Amon A (2015) Aneuploidy‐induced cellular stresses limit autophagic degradation. Genes Dev 29: 2010–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shor E, Fox CA, Broach JR (2013) The yeast environmental stress response regulates mutagenesis induced by proteotoxic stress. PLoS Genet 9: e1003680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. He X, Arrotta N, Radhakrishnan D, Wang Y, Romigh T, Eng C (2013) Cowden syndrome‐related mutations in PTEN associate with enhanced proteasome activity. Cancer Res 73: 3029–3040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glick D, Barth S, Macleod KF (2010) Autophagy: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Pathol 221: 3–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ozpolat B, Benbrook DM (2015) Targeting autophagy in cancer management – strategies and developments. Cancer Manage Res 7: 291–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leu JI‐J, Pimkina J, Frank A, Murphy ME, George DL (2009) A small molecule inhibitor of inducible heat shock protein 70. Mol Cell 36: 15–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, Creighton CJ, Schlabach MR, Westbrook TF, Wong K‐K, Elledge SJ (2009) A genome‐wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell 137: 835–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neckers L, Workman P (2012) Hsp90 molecular chaperone inhibitors: are we there yet? Clin Cancer Res 18: 64–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tong L, Chuang CC, Wu S, Zuo L (2015) Reactive oxygen species in redox cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 367: 18–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee AC, Fenster BE, Ito H, Takeda K, Bae NS, Hirai T, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Howard BH, Finkel T (1999) Ras proteins induce senescence by altering the intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem 274: 7936–7940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vafa O, Wade M, Kern S, Beeche M, Pandita TK, Hampton GM, Wahl GM (2002) c‐Myc can induce DNA damage, increase reactive oxygen species, and mitigate p53 function: a mechanism for oncogene‐induced genetic instability. Mol Cell 9: 1031–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Luo M, He H, Kelley MR, Georgiadis MM (2010) Redox regulation of DNA repair: implications for human health and cancer therapeutic development. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1247–1269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Huber KVM, Salah E, Radic B, Gridling M, Elkins JM, Stukalov A, Jemth A‐S, Göktürk C, Sanjiv K, Strömberg K et al (2014) Stereospecific targeting of MTH1 by (S)‐crizotinib as an anticancer strategy. Nature 508: 222–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gad H, Koolmeister T, Jemth A‐S, Eshtad S, Jacques SA, Ström CE, Svensson LM, Schultz N, Lundbäck T, Einarsdottir BO et al (2014) MTH1 inhibition eradicates cancer by preventing sanitation of the dNTP pool. Nature 508: 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Malhotra D, Portales‐Casamar E, Singh A, Srivastava S, Arenillas D, Happel C, Shyr C, Wakabayashi N, Kensler TW, Wasserman WW et al (2010) Global mapping of binding sites for Nrf2 identifies novel targets in cell survival response through ChIP‐Seq profiling and network analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 5718–5734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhu H, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Zweier JL, Li Y (2005) Role of Nrf2 signaling in regulation of antioxidants and phase 2 enzymes in cardiac fibroblasts: protection against reactive oxygen and nitrogen species‐induced cell injury. FEBS Lett 579: 3029–3036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu C, Huang M‐T, Shen G, Yuan X, Lin W, Khor TO, Conney AH, Kong A‐NT (2006) Inhibition of 7,12‐dimethylbenz(a)anthracene‐induced skin tumorigenesis in C57BL/6 mice by sulforaphane is mediated by nuclear factor E2‐related factor 2. Cancer Res 66: 8293–8296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ramos‐Gomez M, Dolan PM, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW (2003) Interactive effects of nrf2 genotype and oltipraz on benzo[a]pyrene‐DNA adducts and tumor yield in mice. Carcinogenesis 24: 461–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Padmanabhan B, Tong KI, Ohta T, Nakamura Y, Scharlock M, Ohtsuji M, Kang M‐I, Kobayashi A, Yokoyama S, Yamamoto M (2006) Structural basis for defects of Keap1 activity provoked by its point mutations in lung cancer. Mol Cell 21: 689–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ohta T, Iijima K, Miyamoto M, Nakahara I, Tanaka H, Ohtsuji M, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Yokota J, Sakiyama T et al (2008) Loss of Keap1 function activates Nrf2 and provides advantages for lung cancer cell growth. Cancer Res 68: 1303–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shibata T, Ohta T, Tong KI, Kokubu A, Odogawa R, Tsuta K, Asamura H, Yamamoto M, Hirohashi S (2008) Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1‐Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 13568–13573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Solis LM, Behrens C, Dong W, Suraokar M, Ozburn NC, Moran CA, Corvalan AH, Biswal S, Swisher SG, Bekele BN et al (2010) Nrf2 and Keap1 abnormalities in non‐small cell lung carcinoma and association with clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res 16: 3743–3753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Satoh H, Moriguchi T, Takai J, Ebina M, Yamamoto M (2013) Nrf2 prevents initiation but accelerates progression through the Kras signaling pathway during lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 73: 4158–4168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Raj L, Ide T, Gurkar AU, Foley M, Schenone M, Li X, Tolliday NJ, Golub TR, Carr SA, Shamji AF et al (2011) Selective killing of cancer cells by a small molecule targeting the stress response to ROS. Nature 475: 231–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 57. Trachootham D, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Demizu Y, Chen Z, Pelicano H, Chiao PJ, Achanta G, Arlinghaus RB, Liu J et al (2006) Selective killing of oncogenically transformed cells through a ROS‐mediated mechanism by β‐phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Cancer Cell 10: 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Bonnet S, Archer SL, Allalunis‐Turner J, Haromy A, Beaulieu C, Thompson R, Lee CT, Lopaschuk GD, Puttagunta L, Bonnet S et al (2007) A mitochondria‐K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer Cell 11: 37–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB (2009) Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 324: 1029–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Campbell PN (1993) Principles of biochemistry second edition. Biochem Educ 21: 114 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mazurek S, Boschek CB, Hugo F, Eigenbrodt E (2005) Pyruvate kinase type M2 and its role in tumor growth and spreading. Semin Cancer Biol 15: 300–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Erez A, DeBerardinis RJ (2015) Metabolic dysregulation in monogenic disorders and cancer – finding method in madness. Nat Rev Cancer 15: 440–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Chiaradonna F, Gaglio D, Vanoni M, Alberghina L (2006) Expression of transforming K‐Ras oncogene affects mitochondrial function and morphology in mouse fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1757: 1338–1356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Elstrom RL, Bauer DE, Buzzai M, Karnauskas R, Harris MH, Plas DR, Zhuang H, Cinalli RM, Alavi A, Rudin CM et al (2004) Akt stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells. Cancer Res 64: 3892–3899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Matoba S, Kang J‐G, Patino WD, Wragg A, Boehm M, Gavrilova O, Hurley PJ, Bunz F, Hwang PM (2006) p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science 312: 1650–1653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Buzzai M, Bauer DE, Jones RG, Deberardinis RJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Elstrom RL, Thompson CB (2005) The glucose dependence of Akt‐transformed cells can be reversed by pharmacologic activation of fatty acid beta‐oxidation. Oncogene 24: 4165–4173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Son J, Lyssiotis CA, Ying H, Wang X, Hua S, Ligorio M, Perera RM, Ferrone CR, Mullarky E, Shyh‐Chang N et al (2013) Glutamine supports pancreatic cancer growth through a KRAS‐regulated metabolic pathway. Nature 496: 101–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Iurlaro R, León‐Annicchiarico CL, Muñoz‐Pinedo C (2014) Regulation of cancer metabolism by oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Methods Enzymol 542: 59–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, Moran R, Tamagnine J, Parslow D, Armistead S, Lemire K, Orrell J, Teich J et al (2007) Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C125–C136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Halicka HD, Ardelt B, Li X, Melamed MM, Darzynkiewicz Z (1995) 2‐Deoxy‐D‐glucose enhances sensitivity of human histiocytic lymphoma U937 cells to apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor. Cancer Res 55: 444–449 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Geschwind J‐FH, Ko YH, Torbenson MS, Magee C, Pedersen PL (2002) Novel therapy for liver cancer: direct intraarterial injection of a potent inhibitor of ATP production. Cancer Res 62: 3909–3913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]